Abstract

Background

Emerging studies have explored the prognostic value of MIR31HG in cancers, but its role remains elusive. Herein, we aimed to summarize the prognostic potential of MIR31HG in this study.

Methods

Several databases were searched for literature retrieval on Dec 5, 2019. Overall and subgroup analyses were conducted to measure the relationship between MIR31HG expression and clinical outcomes. Moreover, GEPIA was applied for validation of prognostic value of MIR31HG in tumor patients in TCGA dataset.

Results

Overall, seventeen studies with 2573 patients were enrolled. Compared to counterparts, those patients with high MIR31HG expression tended to have shorter RFS. Notably, MIR31HG overexpression predicted unfavorable OS in lung cancer. By contrast, gastrointestinal cancer patients with elevated MIR31HG expression predicted better OS and disease-free survival. Additionally, MIR31HG overexpression was significantly associated with worse clinicopathological features including advanced tumor stage and LNM in lung cancer, but favorable clinical characteristics in gastrointestinal cancer. Moreover, the positive association between MIR31HG and OS in lung cancer was further confirmed in TCGA dataset.

Conclusion

Overexpression of MIR31HG suggested remarkable association with poor prognosis in terms of OS, tumor stage, and LNM in lung cancer, but favorable prognosis in gastrointestinal cancer. Therefore, MIR31HG may serve as a promising prognostic biomarker in multiple cancers.

Keywords: LncRNA MIR31HG,; Sarcoma; Tumor; Prognosis; Overall survival

Background

Cancer is the major cause of death and public health problem worldwide [1]. In spite of notable continuous advances in cancer treatment over the last decades, the patients’ survival rate remains disappointed [2]. Nowadays, only a minority of patients in early clinical stage could benefit from curative approaches, while the rest patients, particularly those with advanced stage, may be resistant to conventional treatments [3]. Against this backdrop, it is necessary to explore reliable biomarkers harboring sufficient sensitivity and specificity for early diagnosis and attractive targets for therapeutic intervention before reaching to advanced stages [4, 5].

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), longer than 200 nucleotides (nt), are defined as highly conserved non-coding RNAs with limited or no protein-coding capacity [6]. LncRNA are involved in diverse physiological and pathological cellular processes [7] by promoting or restraining the protein-coding genes expression [8]. Accumulating evidences have showed that aberrant expression of lncRNA could drive tumor phenotypes, including initiation, invasion, and metastasis, via interacting with other cellular macromolecules [9]. More recently, emerging lncRNAs have been identified and characterized as crucial factors in tumorigenesis, with certain reports highlighting them as biomarkers and targets in various cancers, such as breast cancer anti-estrogen resistance 4 (BCAR4) [10], small nucleolar RNA host gene 16 (SNHG16) [11], and TTN antisense RNA 1 (TTN-AS1) [12].

LncRNA microRNA-31 host gene (MIR31HG), also known as LOC554202 [13], is a newly identified lncRNA with a length of 2166 nt [2, 4]. Meanwhile, MIR31HG was also named as LncHIFCAR (long noncoding HIF-1α co-activating RNA) since it is a hypoxia-inducible lncRNA [4]. P16 (INK4A) is a well-known tumor suppressor, MIR31HG was reported to negatively regulate p16-dependent senescence phenotype [14], suggesting a potential role in carcinogenesis.

Recently, an increasing number of studies have been exploring the prognostic association between MIR31HG and cancers. Abnormal expression of MIR31HG has been reported in a diverse range of cancer types, including osteosarcoma [15], chordoma [16], colorectal cancer (CRC) [17–19], hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [6], lung cancer [2, 20–24], gastric cancer [25], bladder cancer [26], pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [7], oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) [4], breast cancer [13, 27], cervical cancer [28], vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) [29], and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [30, 31]. Furthermore, MIR31HG expression was remarkably associated with survival time, tumor-node metastasis (TNM) stage and carcinogenesis of certain cancers. However, the prognostic significance of MIR31HG may be jeopardized by controversial results, ethnic or geographical limitations, and limited sample size. For example, Sun et al. [30] reported that MIR31HG expression was significantly elevated in ESCC tissues and plasma, and MIR31HG could promote ESCC cell proliferation, migration and invasion [30]. On the contrary, another study revealed that MIR31HG appeared to have lower expression in ESCC tissues and patients with reduced MIR31HG were correlated with malignant clinical features. The contradictory expression patterns of MIR31HG were also found in breast cancer [13, 27], CRC [19, 32, 33] and gastric cancer [25, 34]. In view of these conflicting data, for the first time, we performed this comprehensive meta-analysis of the current evidences in order to determine the predictive value of MIR31HG in various carcinomas.

Materials and methods

Literature search strategy

Studies in relevant with MIR31HG and cancer prognosis were thoroughly searched via PubMed, Web of Science, and Cochrane library (up to Dec 5, 2019). The search strategy was used as following: (“Cancer” OR “Malignancy” OR “Sarcoma” OR “Tumor” OR “Neoplasm” OR “Carcinoma”) AND (“MIR31HG” OR “LOC554202″ OR “LncHIFCAR”) AND (“Long non-coding RNA” OR “LncRNA” OR “long untranslated RNA”OR “lincRNA”) AND (“Prognosis” OR “Prognostic”). The reference lists of enrolled studies were further reviewed to identify relevant articles.

Study selection criteria and data extraction

Studies were included based on the following inclusion criteria: [1] original studies; [2] the diagnosis of cancer was validated by pathology and histology; [3] studies exploring the correlation between MIR31HG and cancers; [4] MIR31HG expression levels were measured and divided into high or low expression group; [5] reporting of at least one of the endpoints: overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS) and relapse-free survival (RFS), et al.; [6] sufficient data: the hazard ratios (HRs) or odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or K-M survival curves were shown; [7] the more recent article was selected if duplicated researches were reported.

On contrary, studies were excluded due to following exclusion criteria: [1] article type: meta-analysis, reviews, editorial material, or case reports; [2] in vivo or in vitro studies without clinical data; [3] sufficient survival data were not provided or cannot be extracted; [4] full text was not accessible; [5] duplicates.

Two independent investigators (CT and XLR) screened and extracted the data from selected studies according to the criteria abovementioned. Any divergence views were resolved by another senior researcher (WCW) to reach a consensus. The following items were provided: first author, year of publication, country, sample size, tumor type, detection methods, follow-up time, and prognostic outcomes. HRs (ORs) and 95% CIs were obtained from the original texts in eligible studies as provided. If not, Engauge Digitizer (version 4.1) would be used to calculate the HR through K-M survival curve as previously described [11].

Quality assessment

Two investigators (JYH and SQL) assessed the quality of studies independently in accordance with the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS). Usually, studies with NOS ≥ 6 were considered as high-quality. The scores of all eligible studies in this study ranged from 6 to 8, which indicated high quality.

Prognosis analysis in GEPIA using TCGA dataset

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/index.html) based on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data [35] was further searched for cross-validation of the expression pattern and prognostic significance of MIR31HG in cancers.

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed by omitting individual study consecutively to evaluate their impact on this study. Begg’s test and Egger’s test were both utilized to evaluate the publication bias.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted by using STATA (version 12.0) and RevMan (Version 5.3). A two-tailed P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. HRs and corresponding 95% CIs were adopted to evaluate the relation between MIR31HG expression and cancer prognosis as well as other clinicopathological characteristics. Heterogeneity of the included studies was assessed by Cochrane’s Q statistic and I2 test. If p<0.05, or I2≥ 50%, a random-effects model shall be applied to calculate the pooled results due to substantial heterogeneity. Otherwise, a fixed-effects model would be used. Subgroup analysis was performed as per the tumor type and follow-up months in case of obvious heterogeneity among the selected studies.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

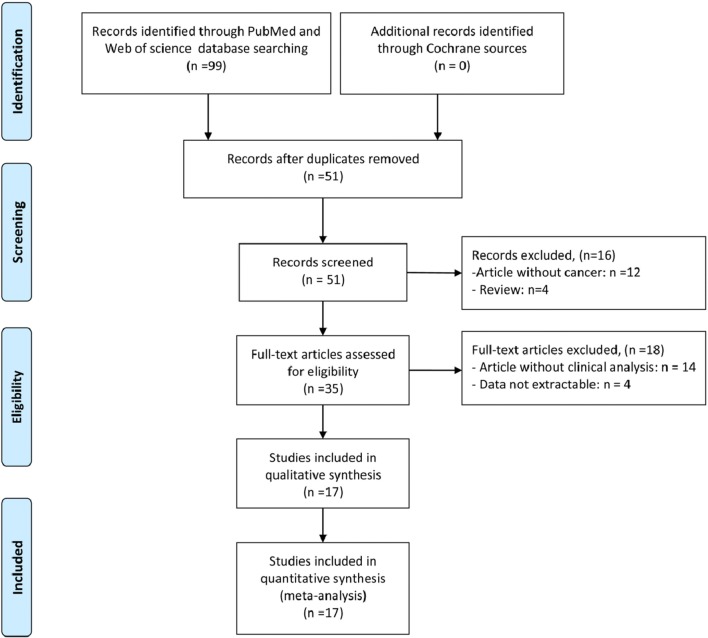

According to the screening criteria, seventeen articles comprising 2573 patients were included in our study [1, 2, 4, 6, 15, 17, 19, 23, 25, 26, 28–33, 36]. All the included studies were related to lncRNA MIR31HG in cancer and comprised clinical data. The study screening flow diagram was shown in Fig. 1. Among the included seventeen articles, twelve types of cancers were identified, including osteosarcoma, cervical cancer, gastric cancer, bladder cancer, CRC, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), HCC, VSCC, ESCC, OSCC, and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). The included studies were performed between 2015 and 2019, and almost all of them were originated in China except one from Norway [17]. The sample size ranged from 16 to 1265. Survival analysis regarding OS, DFS and RFS were measured in twelve studies with follow-up time ranging from 25 to 100 months. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was utilized for analysis of the relative expression level of MIR31HG in tumor tissues except one used RNA sequencing [4]. The cut-off values of MIR31HG expression were median value. NOS scores were calculated for the quality evaluation with value ranging from 6 to 8, indicating that the enrolled studies were of high quality. Details of the abovementioned characteristics of the studies were presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram of study selection

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of eligible studies

| Authors | Publication year | Country | Cancer type | Sample size | Follow-up months | Detection method | Clinical outcomes | Analysis method | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. [27] | 2017 | China | Cervical cancer | 120 | 60 | qRT-PCR | OS | Multivariate | 7 |

| Ding et al. [18] | 2015 | China | CRC | 48 | – | qRT-PCR | – | Multivariate | 6 |

| Eideet al. [16] | 2019 | Norway | CRC | 1265 | 60 | qRT-PCR | RFS | Multivariate | 7 |

| He et al. [25] | 2016 | China | Bladder cancer | 55 | – | qRT-PCR | – | Multivariate | 6 |

| Li et al. [31] | 2018 | China | CRC | 157 | 100 | qRT-PCR | OS, DFS | Multivariate | 7 |

| Ni et al. [28] | 2016 | China | VSCC | 16 | – | qRT-PCR | – | Multivariate | 6 |

| Nie et al. [24] | 2016 | China | Gastric cancer | 42 | 40 | qRT-PCR | OS | Multivariate | 6 |

| Qin et al. [22] | 2018 | China | LUAD | 112 | 85 | qRT-PCR | OS | Multivariate | 7 |

| Ren , et al. [30] | 2017 | China | ESCC | 185 | 60 | qRT-PCR | OS | Multivariate | 6 |

| Shih et al. [4] | 2017 | China | OSCC | 42 | 40 | RNA-seq | OS, RFS | Multivariate | 7 |

| Sun et al. [29] | 2018 | China | ESCC | 53 | – | qRT-PCR | – | Multivariate | 6 |

| Sun et al. [14] | 2019 | China | Osteosarcoma | 40 | – | qRT-PCR | – | Multivariate | 6 |

| Wang et al. [35] | 2018 | China | LSCC | 60 | 85 | qRT-PCR | OS, RFS | Multivariate | 7 |

| Wu et al. [40] | 2019 | China | NSCLC | 50 | 85 | qRT-PCR | OS | Multivariate | 8 |

| Yan et al. [5] | 2018 | China | HCC | 42 | 25 | qRT-PCR | OS | Multivariate | 7 |

| Yang et al. [32] | 2016 | China | CRC | 178 | 70 | qRT-PCR | OS, DFS | Multivariate | 7 |

| Zheng et al. [2] | 2019 | China | NSCLC | 88 | 50 | qRT-PCR | OS | Multivariate | 8 |

CRC colorectal cancer, DFS disease-free survival, ESCC esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, LSCC laryngeal squamous cell cancer, LUAD lung adenocarcinoma, NOS Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, NSCLC Non–small cell lung cancer, OS overall survival, OSCC oral squamous cell carcinoma, qRT-PCR real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, RFS relapse-free survival, VSCC vulvar squamous cell carcinoma

Expression of lncRNA MIR31HG as a prognosis marker in various cancers

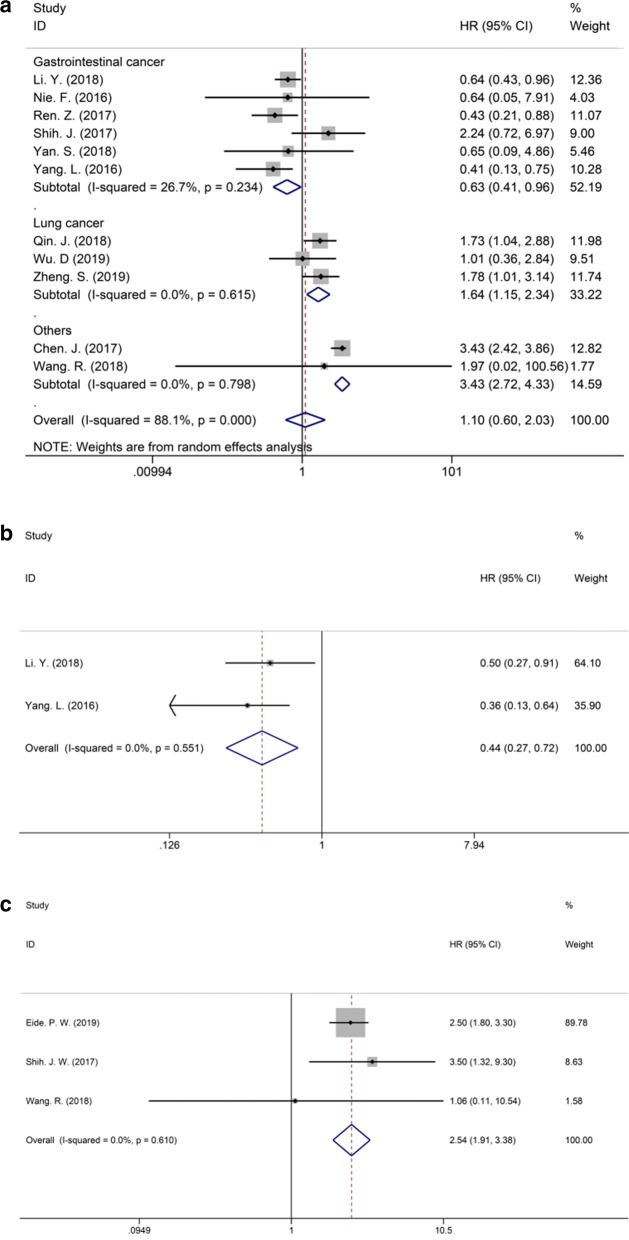

In this study, the association between prognosis and MIR31HG expression were reported in twelve studies. Eleven studies were included for OS meta-analysis. As the result of meta-analysis exhibited obvious heterogeneity (P < 0.001, I2 = 88.1%), subgroup analysis was further conducted to calculate the pooled HRs or ORs and 95% CIs in which the patients were stratified by cancer type (gastrointestinal cancer, lung cancer or others), or follow-up time (more or less than 50 months), as shown in Fig. 2a and Additional file 1: Figure S1, respectively. The gastrointestinal cancer included ESCC, gastric cancer, HCC, and CRC, while the lung cancer consisted of NSCLC and LUAD. Besides, OSCC, LSCC and cervical cancer were grouped in other cancers. The random-effect model was applied to reduce the possible bias. All the pooled HRs and 95% CIs of the overall and subgroup analysis were shown in Table 2. The results demonstrated that elevated expression of the MIR31HG predicted favorable OS in gastrointestinal cancer (HR = 0.56, 95% CI 0.410.77), but unfavorable OS in lung cancer (HR = 1.64, 95% CI 1.152.34) and other cancers (HR = 3.37, 95% CI 2.694.23) (Fig. 2a and Table 2). Interestingly, the pooled results also showed that overexpression of MIR31HG predicted shorter OS in studies with follow-up months less than 50, while no correlation was found in studies with follow-up more than 50 months (Figure S1A).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots describing the overall and subgroup analysis of HRs for association between MIR31HG expression and OS (a), DFS (b), and RFS (c). CI confidence interval, DFS disease-free survival, HR hazard ratio, OS overall survival, RFS relapse-free survival

Table 2.

The pooled results of association between clinical prognosis and MIR31HG expression

| Outcomes | Studies | Participants | HRs and 95% CIs | Model | Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P, I2 | |||||

| OS | |||||

| Total | 11 | 1096 | 1.10 (0.60, 2.03) | Random | < 0.001, 88.1% |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 5 | 604 | 0.56 (0.41, 0.77) | Random | 0.825, 0% |

| Lung cancer | 3 | 270 | 1.64 (1.15, 2.34) | Random | 0.615, 0% |

| Other cancers | 3 | 222 | 3.37 (2.69, 4.23) | Random | 0.746, 0% |

| DFS | 2 | 335 | 0.44 (0.27, 0.72) | Fixed | 0.551, 0% |

| RFS | 3 | 1367 | 2.54 (1.91, 3.38) | Fixed | 0.610, 0% |

CI confidence interval, DFS disease-free survival, HR hazard ratio, OS overall survival, RFS relapse-free survival

Moreover, two studies on CRC for DFS and three studies on various cancers reported available data for RFS were further pooled for measurement. The HR and 95% CI (HR = 0.44, 95% CI 0.270.72) indicated overexpression of MIR31HG predicted favorable DFS in CRC (Fig. 2b). However, overexpression of MIR31HG was correlated with poor RFS (HR = 2.54, 95% CI 1.913.38) (Fig. 2c).

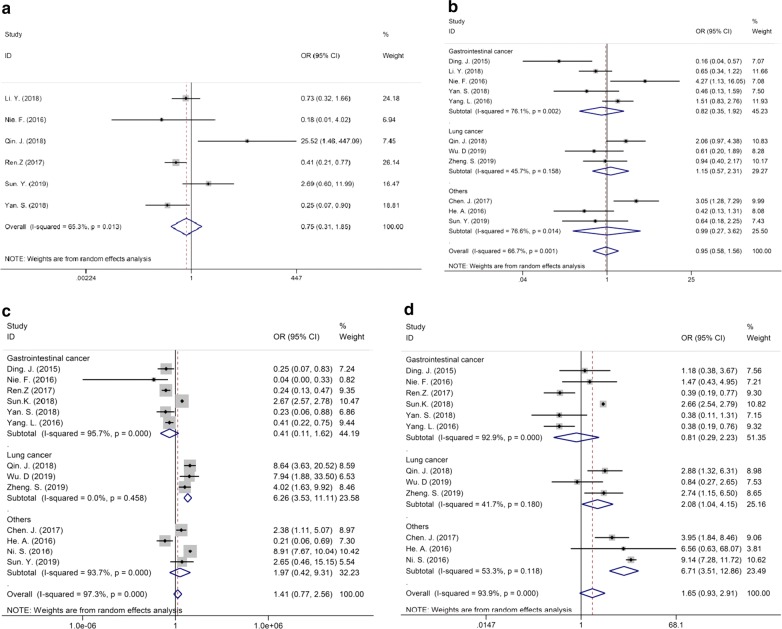

Association between MIR31HG expression and other clinicopathologic parameters

The association between MIR31HG and clinicopathologic features, including clinical stage, lymph node metastasis (LNM), distant metastasis (DM), and tumor size were further analyzed by ORs and their 95% CIs. There was no significant difference in MIR31HG expression detected in DM (OR = 0.75, 95% CI 0.311.85) and tumor size (OR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.581.56), even if the stratified analysis were performed by cancer type (Fig. 3a, b). Although, the pooled overall OR and 95% CI showed no significant difference in MIR31HG expression analysis in various clinical stage (OR = 1.41, 95% CI 0.772.56) and LNM (OR = 1.65, 95% CI 0.932.91), after subgroups analysis by cancer type, the results suggested that upregulated expression of MIR31HG indicated the advanced clinical stage (OR = 6.26, 95% CI 3.5311.11) and higher risk of LNM in lung cancer (OR = 2.08, 95% CI 1.044.15) (Fig. 3c, d).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot describing overall and stratified analysis of relationship between MIR31HG expression and clinicopathological parameters, including DM (a), tumor size (b), advanced clinical stage (c), and LNM (d). DM distant metastasis, LNM lymph node metastasis

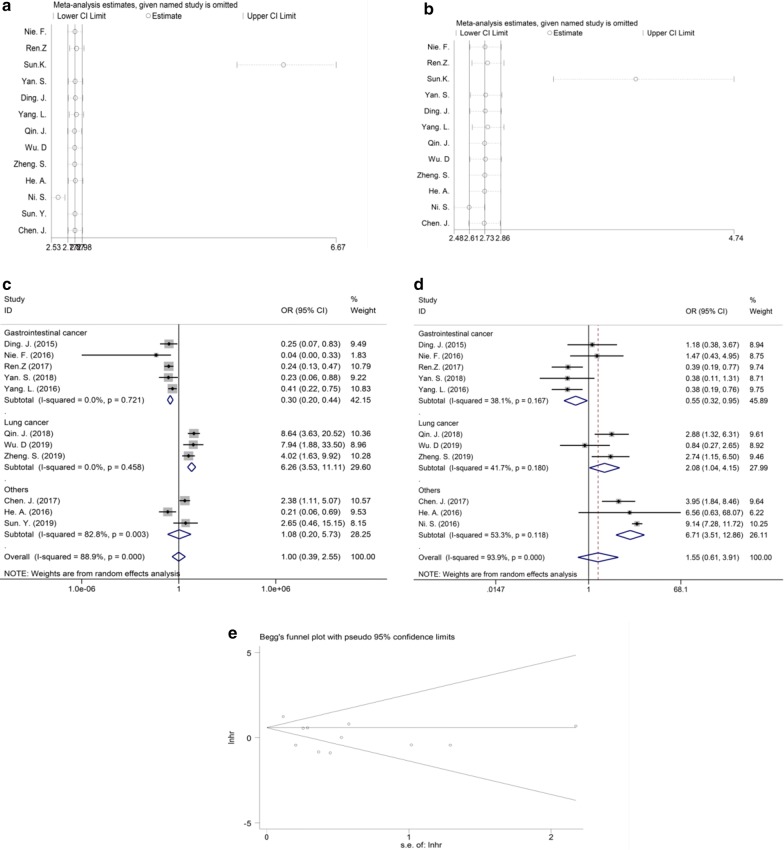

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed to the studies which had more than two articles. All results showed that this meta-analysis was stable except the analysis of clinical stage (Fig. 4a) and LNM (Fig. 4b). After dropping the research performed by Sun et al., the pooled ORs and 95% CIs showed that elevated expression of MIR31HG were negatively associated with clinical stage (OR = 0.30, 95% CI 0.200.44) and LNM risk in gastrointestinal cancer (OR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.320.95) (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity analysis of each study reporting clinical stages (a) and LNM (b). Overall and subgroup analysis of association between MIR31HG expression and advanced clinical stage (c), or LNM (d) after deletion according to the sensitive analysis. Begg’s funnel plot for included studies reporting OS (e) LNM lymph node metastasis, OS overall survival

Publication bias

Publication bias was measured for studies reporting OS by using the funnel plot, Begg’s and Egger’s test. No significant publication bias was observed as the funnel plot showed symmetry, as demonstrated in Fig. 4e. Moreover, the P values for Begg’s and Egger’s test were 0.533 and 0.111, respectively, also indicating the absence of publication bias.

Prognostic analysis in GEPIA using TCGA and GTEx dataset

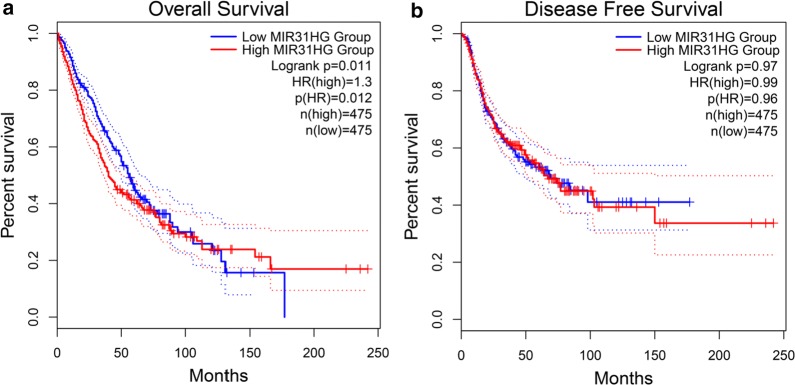

Furthermore, the relationships between expression of MIR31HG and OS/DFS in lung cancers were validated in TCGA and GTEx dataset by using GEPIA as previously described [11]. The results indicated that high MIR31HG expression was correlated with significant shorter OS (HR = 1.3, P = 0.012), but not DFS (HR = 0.99, P = 0.96) (Fig. 5). Besides, the aberrant expression pattern of MIR31HG in multiples cancers and matched normal tissues were also identified, including sarcoma (SARC), LUAD, lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA), breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), rectum adenocarcinoma (READ), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), and esophageal carcinoma (ESCA) (Additional file 1: Figure S1b, c).

Fig. 5.

The prognostic value of MIR31HG in lung cancer patients with tumors in TCGA dataset, including OS (a), DFS (b). DFS disease-free survival, HR hazard ratio, OS overall survival, TCGA The Cancer Genome Atlas

Discussion

Identifying correlative biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity is of great importance in cancer diagnosis and treatment [5]. Recently, with the development of next generation sequencing, lncRNAs are revealed as multifaceted regulators in a wide range of cellular homeostasis [37] via participating in epigenetic, transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of genes [26]. Increasing evidences have established a strong relationship between dysfunction of lncRNAs and cell fate determination as well as disease pathogenesis, such as aging [38], arthritis [39], and cancer [13]. LncRNA MIR31HG, locating at human chromosome 9p21.3 [40] with transcription regulated by methylation of the promoter region [27], was found aberrantly expressed in several types of cancers. Specifically, MIR31HG was found elevated expressed in breast cancer [13], cervical cancer [28], chordoma [16], osteosarcoma [15], lung cancer [2, 23, 41], OSCC [4], PDAC [7], VSCC [29] and LSCC [36, 42, 43]. Nevertheless, the expression levels of MIR31HG was reported down-regulated in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell lines of basal subtype [27], bladder cancer [26], gastric cancer [25], CRC [32, 33], and HCC [6]. Besides, abnormal expression of MIR31HG was deemed as potential biomarker to reflect the clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic outcomes of cancer patients [28]. For instance, increased MIR31HG expression was found both in LUAD/NSCLC tissues when compared with counterparts, and positively associated with unfavorable TNM stage, metastasis, histological differentiated degree, and forecasted shorter OS [2, 23, 41]. Notably, MIR31HG expression was even higher in gefitinib-resistant NSCLC cells, and knockdown of MIR31HG could promote cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, and subsequently induce gefitinib sensitivity [20]. More recently, He J et al. further verified that MIR31HG was also remarkably increased in gefitinib-resistant NSCLC patients, and MIR31HG overexpression contributed to reduced sensitivity of NSCLC cell to gefitinib in vitro [44]. By contrast, Yan S et al. reported that overexpression of MIR31HG significantly inhibited HCC proliferation and metastasis in vitro and impeded tumorigenesis in vivo [6]. In CRC, the MIR31HG expression was negatively correlated with unfavorable prognosis, as indicated by advanced pathologic stage, and lager tumor size [19]. Consistently, Li Y et al. found that high expression of MIR31HG predict high OS and DFS in CRC patients treated with oxaliplatin [32].

Given the prognostic significance of MIR31HG in cancers, in the current study, we firstly explored the association between MIR31HG level and clinical outcomes by performing a meta-analysis containing seventeen literatures with 2573 patients. The pooled results of subgroup analysis as per the tumor types demonstrated that high MIR31HG expression predicted unfavorable OS in patients with lung cancer and other cancers, and poor RFS in all selected studies, respectively. On the contrary, overexpression of MIR31HG was closely associated with favorable OS and DFS in gastrointestinal cancer, indicating a tissue-specific predictive prognosis of MIR31HG in multiple human cancers. Besides, the relationship between expression of MIR31HG and other parameters were analyzed. Consistent with the predictive value of MIR31HG in OS, high level of MIR31HG was also significantly correlated with advanced clinical stage and LNM potential in lung cancer. Previously, the remarkable associations between MIR31HG expressions with LNM risk or tumor stage in gastrointestinal cancer were not noted. However, we found that the study performed by Sun et al. may introduce bias to this meta-analysis, as shown in sensitivity analysis. Therefore, in order to increase the stability of the results, we excluded this study and found that elevated expression of MIR31HG were negatively associated with clinical stage and LNM risk in gastrointestinal cancer. However, no correlation between MIR31HG expression and other clinical characteristics, such as DM and tumor size, were noted. It is worth mentioning that since the studies with regard to the relationship between expression of MIR31HG and other clinical parameters are limited, these results could be biased and therefore needs further confirmation in future studies. Beside, in order to increase the credibility of the results, we performed cross-validation of the results by using TCGA dataset. The results showed the elevated MIR31HG was significantly correlated with poor OS rather than DFS in lung cancer. However, it should be noted that the enrolled studies reporting MIR31HG expression in lung cancers consisted of LUAD and NSCLC, while the cancer types in TCGA were LUAD and LUSC, which may lead to potential difference in predictive value of MIR31HG on clinical outcomes between this meta-analysis and TCGA dataset. Moreover, the limited sample size in TCGA may cause possible bias to the results.

Mechanistically, lncRNA could execute versatile functions in diseases through alternative splicing, epigenetic modulation, chromatin modification, scaffolding/decoy function or acting as molecular sponge [45]. To begin with, given the critical role of MIR31HG in hypoxia-associated malignant progression, MIR31HG was observed to promote tumorigenesis by serving as a HIF-1α co-activator and regulating HIF-1 transcriptional network [4, 42]. For instance, in LSCC, MIR31HG could facilitate cell proliferation, cell cycle progression and suppress apoptosis via HIF-1α and p21 [36]. In OSCC, MIR31HG knockdown impaired the HIF-1α transactivation, sphere-forming ability, metabolic shift and metastatic cascade both in vitro and in vivo [4]. Besides, lncRNA could involve in the competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) regulatory work to function as endogenous miRNA sponge (Table 3) [6]. As the host gene of miR-31, MIR31HG was firstly identified to co-express or modulate the expression of miR-31 in certain cancers [44]. For example, MIR31HG could enhance proliferation, migration and invasion by up-regulating EZH2/miR-31 and then indirectly activating the oncogene RNF144B in chordoma [16]. Yang et al. demonstrated that elevated MIR31HG could inhibit miR-31 expression, and increase RhoA in LSCC, and via which promote cell growth, cell cycle and invasion [43]. In addition to miR-31, other miRNAs were also identified to interact with MIR31HG in carcinogenesis. It was reported that MIR31HG could directly sponge to tumor suppressor- miR-361, rather than miR-31, and in turn regulate cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis via targeting VEGF, FOXM1 and Twist in osteosarcoma [15]. In NSCLC, MIR31HG behaved as an oncogene by inhibiting miR-214 expression, thereby facilitating cancer cell migration and invasion [41]. In HCC cancer, MIR31HG could competitively bind miR-575, and positively regulate ST7L to impair cell proliferation and metastasis [6]. Moreover, MIR31HG could regulate tumorigenesis by targeting a broad spectrum of target genes or pivotal signaling pathways (Table 3). In gastric cancer, MIR31HG may suppress cell proliferation and hinder tumorigenesis partly by regulation of E2F1 and p21 expression [25]. In NSCLC, MIR31HG was found to enhance Wnt/β-catenin pathway, and induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype [2]. Jin et al. identified that MIR31HG was induced by nuclear translocation of NF-κB, and in turn directly bind to IκBα and participated in NF-κB activation, revealing an interaction between MIR31HG and NF-κB in osteogenic differentiation [46]. Of note, MIR31HG could modulate gefitinib resistance partly through EGFR/PI3K/Akt [20, 44] or RAF-MEK-ERK pathways [44]. Furthermore, Zheng S and colleagues discovered that down-regulation of MIR31HG inhibited NSCLC cell proliferation, invasion and EMT phenotype via up-regulating E-cadherin expression, inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin cascade, and down-regulating expression of Twist1 and vimentin [2].

Table 3.

Expression pattern of MIR31HG in cancers and its interaction with miRNAs and target genes

| Tumor type | Expression | Signaling pathways | MiRNAs and target genes | Biological functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteosarcoma | ↑ | / | miR-361, VEGF, FOXM1, Twist | Cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, G1/G arrest, EMT | [14] |

| Chordoma | ↑ | / | miR-31, EZH2, RNF144B | Cell proliferation, migration, invasion, EMT | [15] |

| OSCC | ↑ | / | HIF-1α, p300 | Sphere-forming ability, metabolic shift and metastasis | [4] |

| HNSCC/LSCC | ↑ | / | HIF-1α, p21 | Cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, apoptosis | [35] |

| LSCC | ↑ | / | miR-31, RhoA | Cell growth, cell cycle, invasion | [42] |

| Breast cancer | ↑ | / | / | Cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion | [12] |

| Cervical cancer | ↑ | / | / | Cell proliferation, apoptosis | [27] |

| VSCC | ↑ | / | / | / | [28] |

| NSCLC | ↑ | Wnt/β-catenin | GSK3β, Twist1, Vimentin, E-cadherin | Cell proliferation, invasion, EMT | [2] |

| NSCLC | ↑ | PI3K/Akt | EGFR | Cell proliferation, apoptosis, G0/G1 arrest, gefitinib resistance | [19] |

| NSCLC | ↑ | RAF/MEK/ERK, PI3K/Akt | miR-31, FIH-1, RASA1 | Cell proliferation, clonogenic growth, gefitinib resistance | [43] |

| NSCLC | ↑ | / | miR-214 | Cell migration, invasion | [40] |

| LUAD | ↑ | / | / | Cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest | [22] |

| PDAC | ↑ | / | miR-193b, CCND1, Mcl-1, NT5E, KRAS, uPA, ETS1 | Cell growth, apoptosis, G1/S arrest, invasion | [6] |

| ESCC | ↑ | / | Furin, MMP1 | Cell proliferation, migration, invasion | [29] |

| ESCC | ↓ | / | / | / | [30] |

| Gastric cancer | ↑ | / | p21, E-cadherin | Cell proliferation, migration | [33] |

| Gastric cancer | ↓ | / | E2F1 | Cell proliferation | [24] |

| CRC | ↑ | / | miR-31-5p, MYC, TNF-α/NF-κB, TGF-β, IFN-α/γ | EMT | [16] |

| CRC | ↓ | / | / | Cell proliferation, apoptosis | [18] |

| HCC | ↓ | / | miR-575, ST7L | Cell proliferation, metastasis | [5] |

| Bladder cancer | ↓ | / | / | / | [25] |

Akt protein kinase B, CCND1 cyclin D1, CRC, colorectal cancer, E2F1, E2F transcription factor 1, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, EMT Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, ERK extracellular regulated protein kinases, ESCC esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, ETS1, ETS proto-oncogene 1, transcription factor, EZH2 enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit, FIH-1 hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha inhibitor, FOXM1 forkhead box M1, GSK-3β glycogen synthase kinase-3β, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, HIF-1α hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha, HNSCC head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, IFN-α/γ interferon-α/γ, LSCC laryngeal squamous cell cancer, LUAD lung adenocarcinoma, MMP1 matrix metallopeptidase 1, NSCLC Non–small cell lung cancer, NT5E 5′-nucleotidase ecto, OSCC oral squamous cell carcinoma, PDAC pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, PI3K phosphoinositide 3-kinase, RASA1 RAS p21 protein activator 1, RhoA ras homolog gene family, member A, ST7L suppression of tumorigenicity 7 like, TGF-β transforming growth factor-β, TNF tumor necrosis factor, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, VSCC vulvar squamous cell carcinoma

↑up-regulated, ↓down-regulated

Despite an effort to make a comprehensive analysis, limitations remained inevitably in this study. First, most of the studies were among Asian populations though we do not impose restrictions on region during literature retrieval, which may introduce possible geographical bias. However, since these results have been further confirmed by TCGA dataset [21], it could be more credible to generalize the data to other populations. Second, some HRs with corresponding 95% CIs were indirectly extracted from the Kaplan–Meier (K-M) survival curves, which may introduce possible bias. Third, the cut-off value of MIR31HG levels varied among the selected studies, which may contribute to potential limitation to the clinical use.

Conclusion

Taken together, our study provided evidence that MIR31HG overexpression suggested remarkable association with poor prognosis in terms of OS, tumor stage, and LNM in lung cancer, but favorable prognosis in gastrointestinal cancer. Therefore, MIR31HG may serve as a novel promising prognostic biomarker in patients with multiple cancers. However, more rigorously designed prospective studies with large sample size and complete clinical information are still requested for further confirmation of the results.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Forest plots describing subgroup analysis of HRs for association between MIR31HG expression and OS based on follow-up months (a) and expression pattern of MIR31HG in cancerous tissues and matched normal samples in various cancers (b, c). CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, OS overall survival

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the researchers and study participants for their contributions.

Abbreviations

- Akt

Protein kinase B

- BCAR4

Breast cancer anti-estrogen resistance 4

- BLCA

Bladder urothelial carcinoma

- BRCA

Breast invasive carcinoma

- CCND1

Cyclin D1

- ceRNA

Competing endogenous RNA

- CESC

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma

- CI

Confidence interval

- COAD

Colon adenocarcinoma

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- DM

Distant metastasis

- E2F1

E2F transcription factor 1

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- ERK

Extracellular regulated protein kinases

- ESCA

Esophageal carcinoma

- ESCC

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- ETS1

ETS proto-oncogene 1, transcription factor

- EZH2

Enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit

- FIGO

FOXM1: forkhead box M1

- GEPIA

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis

- GSK-3β

Glycogen synthase kinase-3β

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha

- HNSCC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IFN-α/γ

Interferon-α/γ

- K-M

Kaplan-Meier

- lncRNA

Long noncoding RNA

- LncHIFCAR

Long noncoding HIF-1α co-activating RNA

- LNM

Lymph node metastasis

- LSCC

Laryngeal squamous cell cancer

- LUAD

Lung adenocarcinoma

- LUSC

Lung squamous cell carcinoma

- MIR31HG

MicroRNA-31 host gene

- MMP1

Matrix metallopeptidase 1

- NOS

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

- NSCLC

Non‑small cell lung cancer

- NT5E

5′-Nucleotidase ecto

- OS

Overall survival

- OSCC

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

- PAAD

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- qRT-PCR

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- READ

Rectum adenocarcinoma

- RFS

Relapse-free survival

- RhoA

Ras homolog gene family, member A

- SARC

Sarcoma

- SNHG16

Small nucleolar RNA host gene 16

- ST7L

Suppression of tumorigenicity 7 like

- STAD

Stomach adenocarcinoma

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-β

- TTN-AS1

TTN antisense RNA 1

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VSCC

Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma

Authors’ contributions

CT and ZHL conceptualized the study and designed the methodology of the study. CT and XLR performed the literature retrieval, data analysis and interpretation. JYH and SQL participated in the quality assessment, and assisted in the statistical analysis. LQ and ZXD participated in the data analysis, and assisted in creating the figures. WCW participated in the data interpretation and assisted in manuscript drafting. ZHL and WCW critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81902745), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (2018JJ3716, 2018JJ3762), China Scholarship Council (201806375067, 201806375068), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University (2017zzts231).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chao Tu, Email: tuchao@csu.edu.cn.

Xiaolei Ren, Email: 2204120114@csu.edu.cn.

Jieyu He, Email: hejieyu@csu.edu.cn.

Shuangqing Li, Email: Xiao_3@csu.edu.cn.

Lin Qi, Email: qi.lin@csu.edu.cn.

Zhixi Duan, Email: xiangyadzx@csu.edu.cn.

Wanchun Wang, Email: 604806139@qq.com.

Zhihong Li, Email: lizhihong@csu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12935-020-01194-y.

References

- 1.Wu Y, Hou Y, Xu P, Deng Y, Liu K, Wang M, et al. The prognostic value of YAP1 on clinical outcomes in human cancers. Aging. 2019;11(19):8681–8700. doi: 10.18632/aging.102358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng S, Zhang X, Wang X, Li J. MIR31HG promotes cell proliferation and invasion by activating the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 2019;17(1):221–229. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huo X, Han S, Wu G, Latchoumanin O, Zhou G, Hebbard L, et al. Dysregulated long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for tumorigenesis, disease progression, and liver cancer stem cells. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):165. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0734-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shih JW, Chiang WF, Wu ATH, Wu MH, Wang LY, Yu YL, et al. Long noncoding RNA LncHIFCAR/MIR31HG is a HIF-1alpha co-activator driving oral cancer progression. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15874. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, He W, Zhang S. Seeking for correlative genes and signaling pathways with bone metastasis from breast cancer by integrated analysis. Front Oncol. 2019;9:138. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan S, Tang Z, Chen K, Liu Y, Yu G, Chen Q, et al. Long noncoding RNA MIR31HG inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation and metastasis by sponging microRNA-575 to modulate ST7L expression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):214. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0853-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7.Yang H, Liu P, Zhang J, Peng X, Lu Z, Yu S, et al. Long noncoding RNA MIR31HG exhibits oncogenic property in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and is negatively regulated by miR-193b. Oncogene. 2016;35(28):3647–3657. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atianand MK, Caffrey DR, Fitzgerald KA. Immunobiology of long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Immunol. 2017;35:177–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitt AM, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs in cancer pathways. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(4):452–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tu C, Ren X, He J, Zhang C, Chen R, Wang W, et al. The value of LncRNA BCAR4 as a prognostic biomarker on clinical outcomes in human cancers. J Cancer. 2019;10(24):5992–6002. doi: 10.7150/jca.35113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C, Ren X, He J, Wang W, Tu C, Li Z. The prognostic value of long noncoding RNA SNHG16 on clinical outcomes in human cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:261. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-0971-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu D, Lu C, Qu X, Li P, Chen K, Shan L, et al. LncRNA TTN-AS1 regulates osteosarcoma cell apoptosis and drug resistance via the miR-134-5p/MBTD1 axis. Aging. 2019;11(19):8374–8385. doi: 10.18632/aging.102325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi Y, Lu J, Zhou J, Tan X, He Y, Ding J, et al. Long non-coding RNA Loc554202 regulates proliferation and migration in breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446(2):448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montes M, Nielsen MM, Maglieri G, Jacobsen A, Hojfeldt J, Agrawal-Singh S, et al. The lncRNA MIR31HG regulates p16(INK4A) expression to modulate senescence. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6967. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Y, Jia X, Wang M, Deng Y. Long noncoding RNA MIR31HG abrogates the availability of tumor suppressor microRNA-361 for the growth of osteosarcoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:8055–8064. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S214569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma X, Qi S, Duan Z, Liao H, Yang B, Wang W, et al. Long non-coding RNA LOC554202 modulates chordoma cell proliferation and invasion by recruiting EZH2 and regulating miR-31 expression. Cell Prolif. 2017;50(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Eide PW, Eilertsen IA, Sveen A, Lothe RA. Long noncoding RNA MIR31HG is a bona fide prognostic marker with colorectal cancer cell-intrinsic properties. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(11):2843–2853. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang H, Wang Z, Wu J, Ma R, Feng J. Long noncoding RNAs predict the survival of patients with colorectal cancer as revealed by constructing an endogenous RNA network using bioinformation analysis. Cancer Med. 2019;8(3):863–873. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding J, Lu B, Wang J, Wang J, Shi Y, Lian Y, et al. Long non-coding RNA Loc554202 induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells via the caspase cleavage cascades. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:100. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0217-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang B, Jiang H, Wang L, Chen X, Wu K, Zhang S, et al. Increased MIR31HG lncRNA expression increases gefitinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines through the EGFR/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(5):3494–3500. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu B, Chen Y, Yang J. LncRNAs are altered in lung squamous cell carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(15):24275–24291. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ning P, Wu Z, Hu A, Li X, He J, Gong X, et al. Integrated genomic analyses of lung squamous cell carcinoma for identification of a possible competitive endogenous RNA network by means of TCGA datasets. Peer J. 2018;6:e4254. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qin J, Ning H, Zhou Y, Hu Y, Yang L, Huang R. LncRNA MIR31HG overexpression serves as poor prognostic biomarker and promotes cells proliferation in lung adenocarcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;99:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sui J, Yang S, Liu T, Wu W, Xu S, Yin L, et al. Molecular characterization of lung adenocarcinoma: a potential four-long noncoding RNA prognostic signature. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(1):705–714. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nie FQ, Ma S, Xie M, Liu YW, De W, Liu XH. Decreased long noncoding RNA MIR31HG is correlated with poor prognosis and contributes to cell proliferation in gastric cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(6):7693–7701. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4644-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He A, Chen Z, Mei H, Liu Y. Decreased expression of LncRNA MIR31HG in human bladder cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2016;17(2):231–236. doi: 10.3233/CBM-160635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Augoff K, McCue B, Plow EF, Sossey-Alaoui K. miR-31 and its host gene lncRNA LOC554202 are regulated by promoter hypermethylation in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J, Zhu J. Elevated expression levels of long non-coding RNA, Loc554202, are predictive of poor prognosis in cervical cancer. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2017;243(3):165–172. doi: 10.1620/tjem.243.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ni S, Zhao X, Ouyang L. Long non-coding RNA expression profile in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma and its clinical significance. Oncol Rep. 2016;36(5):2571–2578. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun K, Zhao X, Wan J, Yang L, Chu J, Dong S, et al. The diagnostic value of long non-coding RNA MIR31HG and its role in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Life Sci. 2018;202:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren ZP, Chu XY, Xue ZQ, Zhang LB, Wen JX, Deng JQ, et al. Down-regulation of lncRNA MIR31HG correlated with aggressive clinicopathological features and unfavorable prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21(17):3866–3870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Xin S, Wu H, Xing C, Duan L, Sun W, et al. High expression of microRNA31 and its host gene LOC554202 predict favorable outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer treated with oxaliplatin. Oncol Rep. 2018;40(3):1706–1724. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang LWH, Xiao HJ. Long non-coding RNA Loc554202 expression as a prognostic factor in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(20):4243–4247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin Y, Zhang CS, Li SJ, Li Z, Sun FB. LncRNA LOC554202 promotes proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells through regulating p21 and E-cadherin. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(24):8690–8697. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201812_16634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T, Zhang Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W556–W560. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang R, Ma Z, Feng L, Yang Y, Tan C, Shi Q, et al. LncRNA MIR31HG targets HIF1A and P21 to facilitate head and neck cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenesis by promoting cell-cycle progression. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):162. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0916-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huarte M. The emerging role of lncRNAs in cancer. Nat Med. 2015;21(11):1253–1261. doi: 10.1038/nm.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He J, Tu C, Liu Y. Role of lncRNAs in aging and age-related diseases. Aging Med. 2018;1(2):158–175. doi: 10.1002/agm2.12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zou Y, Xu S, Xiao Y, Qiu Q, Shi M, Wang J, et al. Long noncoding RNA LERFS negatively regulates rheumatoid synovial aggression and proliferation. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(10):4510–4524. doi: 10.1172/JCI97965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajbhandari R, McFarland BC, Patel A, Gerigk M, Gray GK, Fehling SC, et al. Loss of tumor suppressive microRNA-31 enhances TRADD/NF-kappaB signaling in glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(19):17805–17816. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dandan W, Jianliang C, Haiyan H, Hang M, Xuedong L. Long noncoding RNA MIR31HG is activated by SP1 and promotes cell migration and invasion by sponging miR-214 in NSCLC. Gene. 2019;692:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng L, Wang R, Lian M, Ma H, He N, Liu H, et al. Integrated analysis of long noncoding rna and mrna expression profile in advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0169232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang S, Wang J, Ge W, Jiang Y. Long non-coding RNA LOC554202 promotes laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma progression through regulating miR-31. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(8):6953–6960. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He J, Jin S, Zhang W, Wu D, Li J, Xu J, et al. Long non-coding RNA LOC554202 promotes acquired gefitinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer through upregulating miR-31 expression. J Cancer. 2019;10(24):6003–6013. doi: 10.7150/jca.35097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bar C, Chatterjee S, Thum T. Long noncoding RNAs in cardiovascular pathology, diagnosis, and therapy. Circulation. 2016;134(19):1484–1499. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jin C, Jia L, Huang Y, Zheng Y, Du N, Liu Y, et al. Inhibition of lncRNA MIR31HG promotes osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells. 2016;34(11):2707–2720. doi: 10.1002/stem.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Forest plots describing subgroup analysis of HRs for association between MIR31HG expression and OS based on follow-up months (a) and expression pattern of MIR31HG in cancerous tissues and matched normal samples in various cancers (b, c). CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, OS overall survival

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.