Abstract

Background

Inflammation is one of the factors associated with prostate cancer. The cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) plays an important role in inflammation. Several studies have focused on the association between TNF-α polymorphisms and prostate cancer development. Our meta-analysis aimed to estimate the association between TNF-α rs1800629 (− 308 G/A), rs361525 (− 238 G/A) and rs1799724 polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk.

Methods

Eligible studies were identified from electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, Wanfang and CNKI) using keywords: TNF-α, polymorphism, prostate cancer, until Nov 15, 2019. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were applied to determine the association from a quantitative point-of-view. Publication bias and sensitivity analysis were also applied to evaluate the power of current study. All statistical analyses were done with Stata 11.0 software.

Results

Twenty-two different articles were included (22 studies about rs1800629; 8 studies for rs361525 and 5 studies related to rs1799724). Overall, no significant association was found between rs1800629 and rs1799724 polymorphisms and the risk of prostate cancer in the whole (such as: OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.92–1.16, P = 0.580 in the allele for rs1800629; OR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.84–1.07, P = 0.381 in the allele for rs1799724). The rs361525 polymorphism also had no association with prostate cancer in the cases (OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.66–1.32, P = 0.684 in the allele) and ethnicity subgroup. The stratified subgroup of genotype method, however, revealed that the rs361525 variant significantly decreased the risk of prostate cancer in the Others (OR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.47–0.89, P = 0.008, A-allele vs G-allele) and PCR-RFLP (OR = 2.68, 95% CI = 1.00–7.20, P = 0.050, AG vs GG or AA+AG vs GG) methods.

Conclusions

In summary, the findings of the current meta-analysis indicate that the TNF-α rs1800629, rs361525 and rs1799724 polymorphisms are not correlated with prostate cancer development, although there were some pooled positive results. Further well-designed studies are necessary to form more precise conclusions.

Keywords: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, Prostate cancer, Polymorphism, Meta-analysis, Susceptibility

Background

Prostate cancer (PCA) is the second most frequent tumor in men worldwide, with 1.27 million new cases and 0.35 million deaths in 2018 [1, 2]. The incidence and mortality of PCA are correlated with increasing age, and the average age at the time of diagnosis is over 66 years in some regions. Additionally, there is also evidence of an association between ethnicity and PCA; for example, the incidence rate in African-American men is 158.3 newly diagnosed cases/100,000, which is higher than that in White men, and their mortality is about twice that of White men according to Panigrahi et al. [3]. Several factors may contribute to this disparity, such as differences in diet, habits/customs, and genetic/environmental factors.

There is growing evidence that chronic inflammation is involved in the regulation of cellular events in prostate carcinogenesis, including disruption of the immune response and regulation of the tumor microenvironment [4]. One of the best surrogates of chronic inflammation in PCA is the cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [5, 6]. Chadha et al. indicated the median TNF-α levels in serum was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the control group (5.12 pg/ml) than in the localized PCA group (2.20 pg/ml). Moreover, TNF-α was the strongest single predictor between localized and metastatic PCA (Area Under Curve, AUC = 0.992) and was higher than the PSA value (AUC = 0.963). Taken together, these results suggest that TNF-α may be considered a novel serum biomarker for the diagnosis of PCA [7].

The TNF-α gene, also termed DIF/TNFSF2/TNLG1F, is located in the class III region of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC III) and mapped to chromosome 6p21.33 with 4 exons [8, 9]. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in this gene have been widely reported and have been associated with the risk of several cancers, such as PCA, breast cancer, and lung cancer [10–12]. Rs1800629 is one of the most common SNPs, with a G to A transition at the − 308 nucleotide in the promoter of the transcription initiation site, which may affect the serum expression of TNF-α [13]. Another common SNP named rs361525 is located at the − 238 site, where a G to A substitution is shown, and may influence TNF-α in the serum [14]. The rs1799724 (C to T transition) and rs1799964 (T to C transition) SNPs have been reported in recent years [15, 16]; however, to date, it is not known whether these two SNPs can affect the expression of TNF-α.

Previously, two meta-analyses focused on TNF-α polymorphisms and PCA risk have been published: Cai et al. identified 12 case-control studies and concluded that the rs1800629 polymorphism had an increased association with PCA risk in the GA vs. GG genetic model (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.04–1.37) [17]. Ma et al., however, suggested that the rs361525 polymorphism was not associated with PCA, and the rs1800629 polymorphism, which is also the susceptible SNP for PCA, only had a significant association in healthy volunteers (AG vs. GG: OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.04–2.08) [18]. Due to these inconclusive results, as well as the publication of some additional studies, it was necessary to re-combine all of the articles, including 22 different case-control studies [15, 16, 19–36], to conduct an updated meta-analysis.

Methods

Literature search and inclusion criteria

We performed a literature search for all eligible articles regarding the association between four TNF-α polymorphisms and PCA risk on multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, Embase, Wanfang and CNKI, using the following keywords: ‘tumor necrosis factor alpha OR TNF-α’ AND ‘polymorphism OR variation OR mutation’ AND ‘prostate cancer OR carcinoma OR neoplasm OR tumor’ until Nov 15, 2019.

Relevant studies were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) case-control studies addressing the correlation between a TNF-α polymorphism and PCA risk; (2) studies containing sufficient genotype data on both the cases and controls; and (3) the largest sample sizes were selected among articles with overlapping study groups. The exclusion criteria were (1) conference abstracts, case reports, reviews and duplicated information; and (2) inadequate genotype data.

Data extraction

The following data were gathered from each eligible study: the first author’s name, publication year, country, sample size for the case and control groups, source of control, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) of the controls, genotyping techniques and the genotype of the cases and controls.

Statistical analysis

The strength of the association between the four TNF-α polymorphisms and PCA susceptibility was measured by the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) in 3 (allele, heterozygous and dominant) genetic models. The significance of the pooled OR was assessed by the Z-test, and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The between-study heterogeneity was evaluated by the Q-test. In cases where significant heterogeneity was detected, if P < 0.1, indicating the presence of heterogeneity, a random-effects model was selected; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was applied [37, 38]. Publication bias was inspected using Begg’s test, and Egger’s test was used to measure the degree of asymmetry. In both tests, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant [39]. The HWE of the control group was specified through the chi-square test, where P < 0.05 was considered significant [40]. Sensitivity analyses were done to evaluate whether a single study influenced the overall pooled results by omitting each study in turn. All statistical tests used in this study were performed using Stata (version 11.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of selected studies

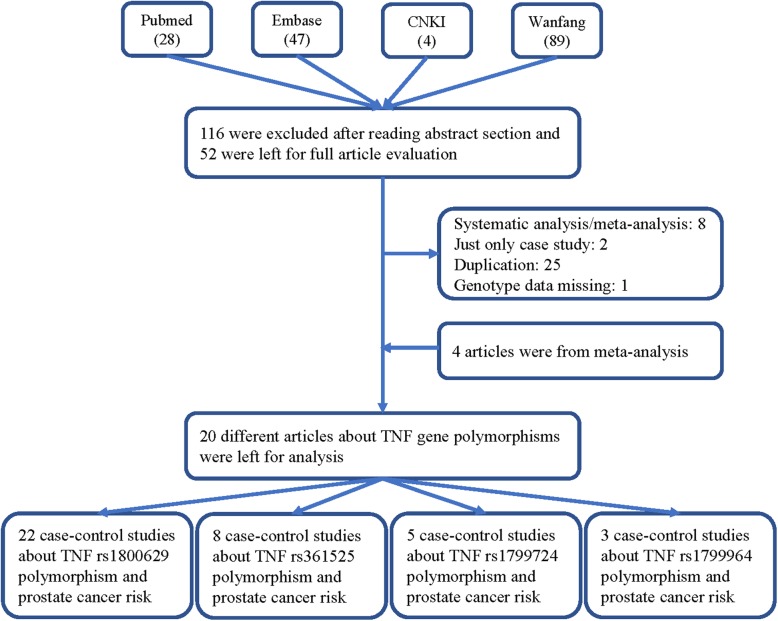

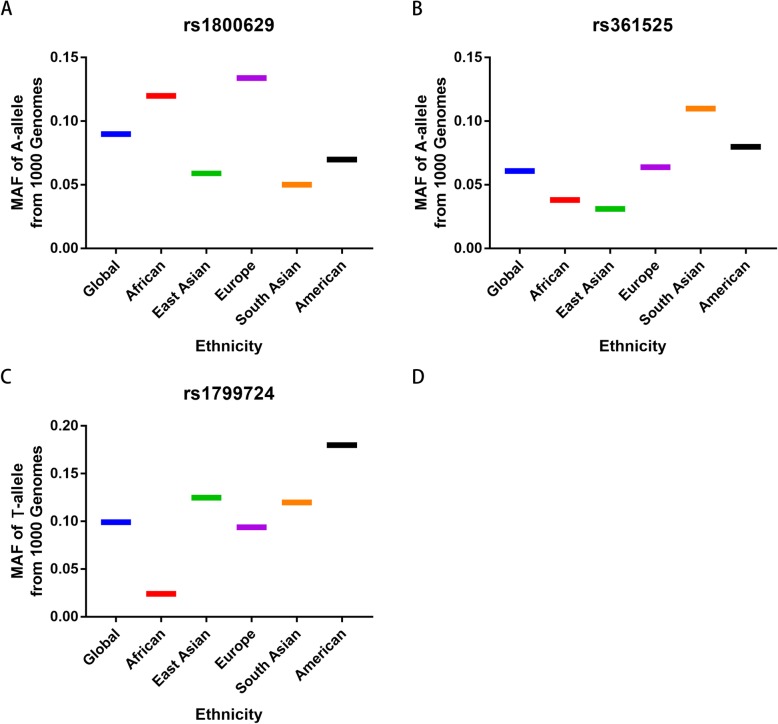

A total of 168 published articles were retrieved from the PubMed, Embase, Wanfang and CNKI databases in accordance with the selection criteria. Finally, 20 different articles (22 case-control studies) were included in our meta-analysis (Table 1, Fig. 1) [15, 16, 19–36]. Of the 22 studies, TNF-α rs1800629 was analyzed in 22 studies; rs361525, in 8 studies; rs1799724, in 5 studies; and rs1799964, in 3 studies. Only three available reports investigated rs1799964 and PCA susceptibility, so we did not analyze this association. Table 1 shows the features and related information of the included studies. In addition, we checked the Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) reported for the five main worldwide populations in the 1000 Genomes Browser for each SNP: East Asian (EAS), European (EUR), African (AFR), American (AMR), and South Asian (SAS) (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies eligible for current meta-analysis

| Author | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Case | Control | SOC | Cases | Controls | HWE | Genotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM | MW | WW | MM | MW | WW | |||||||||

| rs1800629 | ||||||||||||||

| Jones | 2013 | USA | African-American | 279 | 535 | HB | 5 | 103 | 171 | 14 | 153 | 368 | 0.687 | Illumina’s Golden gate |

| Zabaleta | 2008 | USA | African-American | 67 | 130 | HB | 2 | 9 | 56 | 3 | 33 | 94 | 0.958 | Sequence |

| Berhane | 2012 | India | Asian | 150 | 150 | HB | 6 | 24 | 120 | 1 | 18 | 131 | 0.662 | ARMS-PCR |

| Wu | 2003 | China-Taiwan | Asian | 96 | 126 | HB | 2 | 20 | 74 | 1 | 22 | 103 | 0.882 | PCR-RFLP |

| Alidoost | 2019 | Iran | Asian | 100 | 110 | HB | 0 | 16 | 84 | 0 | 14 | 96 | 0.476 | PCR-RFLP/ARMS-PCR |

| Kesarwani | 2009 | India | Asian | 197 | 256 | HB | 1 | 21 | 175 | 4 | 37 | 215 | 0.115 | PCR-RFLP |

| Ali | 2019 | Iraq | Asian | 30 | 30 | PB | 12 | 18 | 0 | 24 | 6 | 0 | 0.543 | PCR-RFLP |

| Ge | 2007 | China | Asian | 245 | 245 | HB | 2 | 39 | 204 | 2 | 48 | 195 | 0.609 | TaqMan |

| Dluzniewski | 2012 | USA | Caucasian | 468 | 468 | HB | 14 | 113 | 341 | 6 | 126 | 336 | 0.125 | MassArray |

| Pardo | 2019 | Venezuela | Caucasian | 40 | 40 | HB | 0 | 6 | 34 | 0 | 11 | 29 | 0.313 | PCR-RFLP |

| Zabaleta | 2008 | USA | Caucasian | 479 | 400 | HB | 9 | 148 | 322 | 10 | 118 | 272 | 0.505 | Sequence |

| Sáenz-López | 2008 | Spain | Caucasian | 296 | 310 | PB | 5 | 70 | 221 | 2 | 52 | 256 | 0.714 | TaqMan |

| Moore | 2009 | USA | Caucasian | 949 | 857 | PB | 21 | 228 | 700 | 11 | 205 | 641 | 0.231 | TaqMan |

| Danforth | 2008 | USA | Caucasian | 1155 | 1380 | PB | 26 | 336 | 793 | 45 | 418 | 926 | 0.795 | TaqMan/MGBEclipse assay |

| Danforth | 2008 | USA | Caucasian | 1111 | 1125 | PB | 25 | 294 | 792 | 33 | 286 | 806 | 0.217 | TaqMan/MGBEclipse assay |

| Ribeiro | 2012 | Portugal | Caucasian | 449 | 557 | PB | 8 | 115 | 326 | 7 | 143 | 407 | 0.155 | TaqMan |

| Wang | 2009 | USA | Caucasian | 251 | 250 | PB | 12 | 79 | 160 | 9 | 69 | 172 | 0.529 | TaqMan |

| Bandil | 2017 | India | Asian | 105 | 115 | HB | 9 | 15 | 81 | 4 | 7 | 104 | < 0.001 | ARMS-PCR |

| Omrani | 2008 | Iran | Asian | 41 | 105 | HB | 0 | 36 | 5 | 3 | 99 | 3 | < 0.001 | ASO-PCR |

| McCarron | 2002 | United Kingdom | Caucasian | 239 | 220 | HB | 6 | 66 | 167 | 13 | 57 | 150 | 0.023 | ARMS-PCR |

| OH | 2000 | USA | Caucasian | 73 | 73 | HB | 0 | 53 | 20 | 0 | 53 | 20 | < 0.001 | allele-specific PCR |

| Zhang | 2010 | USA | Caucasian | 116 | 128 | PB | 116 | 128 | CBMALD-TOF-MS | |||||

| rs361525 | ||||||||||||||

| Pardo | 2019 | Venezuela | Caucasian | 40 | 40 | HB | 0 | 4 | 36 | 0 | 1 | 39 | 0.936 | PCR-RFLP |

| OH | 2000 | USA | Caucasian | 73 | 73 | HB | 0 | 23 | 50 | 0 | 23 | 50 | 0.11 | allele-specific PCR |

| Zabaleta | 2008 | USA | Caucasian | 471 | 385 | HB | 6 | 41 | 424 | 0 | 39 | 346 | 0.295 | Sequence |

| Alidoost | 2019 | Iran | Asian | 100 | 110 | HB | 0 | 10 | 90 | 0 | 5 | 105 | 0.807 | PCR-RFLP/ARMS-PCR |

| Danforth | 2008 | USA | Caucasian | 1114 | 1126 | PB | 1 | 121 | 992 | 3 | 100 | 1023 | 0.737 | TaqMan/MGBEclipse assay |

| Ge | 2007 | China | Asian | 245 | 245 | HB | 0 | 10 | 235 | 0 | 22 | 223 | 0.461 | TaqMan |

| Zabaleta | 2008 | USA | African-American | 64 | 126 | HB | 0 | 6 | 58 | 2 | 10 | 114 | 0.006 | Sequence |

| Bandil | 2017 | India | Asian | 105 | 115 | HB | 12 | 60 | 33 | 20 | 86 | 9 | < 0.001 | ARMS-PCR |

| rs1799724 | ||||||||||||||

| Danforth | 2008 | USA | Caucasian | 1139 | 1378 | PB | 13 | 203 | 923 | 14 | 254 | 1110 | 0.9 | TaqMan/MGBEclipse assay |

| Danforth | 2008 | USA | Caucasian | 1108 | 1101 | PB | 17 | 183 | 908 | 19 | 220 | 862 | 0.257 | TaqMan/MGBEclipse assay |

| Kesarwani | 2009 | India | Asian | 197 | 256 | HB | 4 | 57 | 136 | 4 | 56 | 196 | 1 | PCR-RFLP |

| Zabaleta | 2008 | USA | African-American | 464 | 372 | HB | 6 | 59 | 399 | 8 | 41 | 323 | < 0.001 | Sequence |

| Zabaleta | 2008 | USA | Caucasian | 6 | 14 | HB | 3 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 7 | < 0.001 | Sequence |

| rs1799964 | ||||||||||||||

| Danforth | 2008 | USA | Caucasian | 1142 | 1375 | PB | 60 | 361 | 721 | 58 | 441 | 876 | 0.791 | TaqMan/MGBEclipse assay |

| Danforth | 2008 | USA | Caucasian | 1143 | 1155 | PB | 54 | 370 | 719 | 64 | 377 | 714 | 0.129 | TaqMan/MGBEclipse assay |

| Kesarwani | 2009 | India | Asian | 197 | 256 | HB | 90 | 64 | 43 | 83 | 91 | 82 | < 0.001 | PCR-RFLP |

HB hospital-based, PB population-based, SOC source of control, PCR-FLIP polymerase chain reaction and restrictive fragment length polymorphism; ARMS amplification refractory mutation system, HWE Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium of control group, W wild type-allele, M mutant-allele

Fig. 1.

A flowchart illustrating the search strategy about TNF-α rs1800629, rs361525, rs1799724 and rs1799964 polymorphisms and PCA risk was shown

Fig. 2.

MAF for the TNF-α rs1800629, rs361525 and rs1799724 polymorphsms from 1000 Genomes Browser. Vertical line, MAF; Horizontal line, ethnicity type. EAS: East Asian; EUR: European; AFR: African; AMR: American; SAS: South Asian

Pooled analysis results

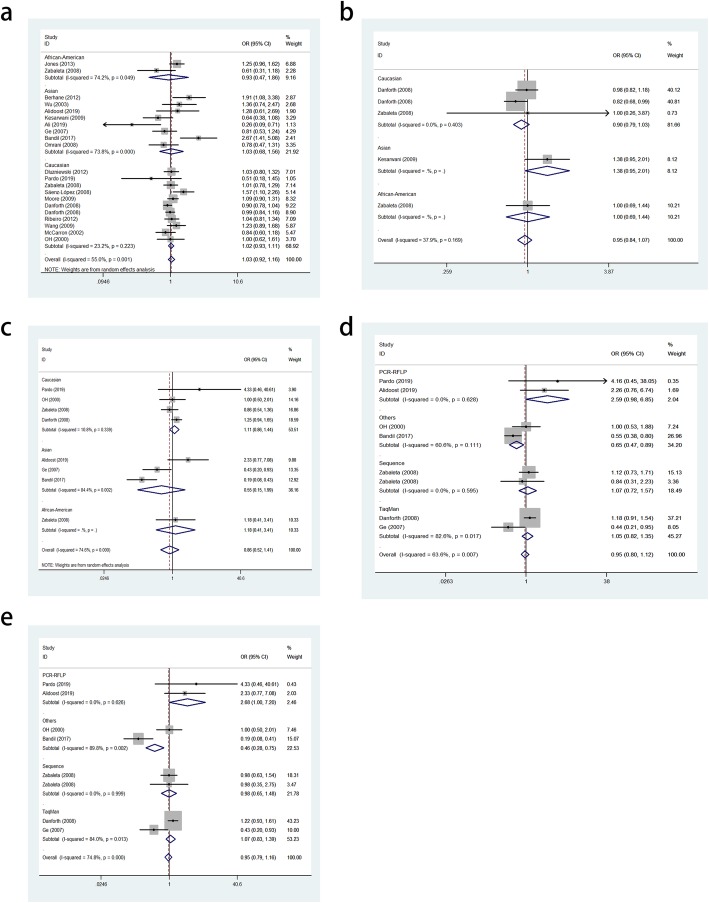

Overall, the findings did not support an association between the TNF-α rs1800629 polymorphism and PCA susceptibility in the allele (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.92–1.16, P = 0.580, Fig. 3a), heterozygous (OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.93–1.17, P = 0.486) and dominant (OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.94–1.18, P = 0.353) genetic models. To evaluate the power and stability, some studies not consistent with HWE were excluded, and similar results were obtained. Stratified analyses by ethnicity, source of control and genotyping methods were conducted, and no significant association was detected (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis. a. Forest plots of TNF-α rs1800629 polymorphism and PCA risk (A-allele vs. G-allele). b. Forest plot of TNF-α rs1799724 polymorphism and PCA risk (T-allele vs. C-allele). c. Forest plot of TNF-α rs361525 polymorphism and PCA risk (AA vs. GG). d. Forest plot of TNF-α rs361525 polymorphism and PCA risk (A-allele vs. G-allele) on subgroup of genotyping method (Others). e. Forest plot of TNF-α rs361525 polymorphism and PCA risk (A-allele vs. G-allele) on subgroup of genotyping method (PCR-RFLP)

Table 3.

Publication bias tests (Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test for publication bias test) for rs1800629 and rs361525 polymorphisms

| Egger’s test | Begg’s test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic type | Coefficient | Standard error | t | P value | 95%CI of intercept | z | P value |

| rs1800629 | |||||||

| A-allele vs. G-allele | 0.009 | 0.681 | 0.01 | 0.989 | (−1.418–1.437) | 0.21 | 0.833 |

| AG vs. GG | 0.331 | 0.528 | 0.63 | 0.539 | (−0.779–1.440) | 0.1 | 0.922 |

| AA+AG vs. GG | 0.046 | 0.619 | 0.07 | 0.941 | (−1.249–1.341) | 0.33 | 0.74 |

| rs361525 | |||||||

| A-allele vs. G-allele | −0.216 | 1.259 | 0.17 | 0.87 | (−2.866–3.297) | 0.12 | 0.902 |

| AG vs. GG | −0.293 | 0.935 | −0.3 | 0.765 | (−2.582–1.996) | − 0.12 | 1 |

| AA+AG vs. GG | −0.303 | 0.938 | −0.3 | 0.757 | (−2.599–1.991) | − 0.12 | 1 |

For the TNF-α rs1799724 polymorphisms, no significant associations were identified in the cases and subgroups. Further, the rs1799724 polymorphism was not significantly associated with PCA in the allele (OR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.84–1.07, P = 0.381, Fig. 3b), heterozygous (OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.80–1.27, P = 0.951) and dominant genetic models (OR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.83–1.07, P = 0.390).

For the TNF-α rs361525 polymorphism, although no association was found in the allele (OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.66–1.32, P = 0.684), heterozygous (OR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.52–1.41, P = 0.542, Fig. 3c) and dominant models (OR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.52–1.39, P = 0.525), for HWE, ethnicity and source of control, pooled significant relationships were observed in genotyping subgroups, such as Others (OR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.47–0.89, P = 0.008 for A-allele vs. G-allele, Fig. 3d) and PCR-RFLP (OR = 2.68, 95% CI = 1.00–7.20, P = 0.050, Fig. 3e).

Heterogen

Heterogeneity and publication bias

As shown in Table 2, heterogeneity among the studies was found in all three genetic comparisons for all 3 SNPs (rs1800629, rs361525 and rs1799724).

Table 2.

The pooled ORs and 95%CIs for the association between TNF polymorphisms and prostate cancer susceptibility in total and stratified analysis

| Variables | N | Case/Control | M-allele vs. W-allele OR(95%CI) PhP |

MW vs. WW OR(95%CI) PhP |

MM + MW vs. WW OR(95%CI) PhP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1800629 | |||||

| Total | 22 | 6936/7619 | 1.03 (0.92–1.16)0.001 0.580 | 1.04 (0.93–1.17)0.040 0.486 | 1.06 (0.94–1.18)0.013 0.353 |

| HWE | 18 | 7485/6792 | 1.03 (0,92–1.16)0.006 0.584 | 1.04 (0,93–1.16)0.091 0.509 | 1.05 (0,94–1.17)0.051 0.429 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Asian | 8 | 964/1137 | 1.03 (0.68–1.56)0.000 0.881 | 1.04 (0.70–1.56)0.038 0.845 | 1.09 (0.70–1.71)0.006 0.698 |

| Caucasian | 12 | 5626/5817 | 1.01 (0.94–1.08)0.223 0.838 | 1.02 (0.94–1.11)0.525 0.672 | 1.02 (0.94–1.11)0.433 0.625 |

| African-American | 2 | 346/665 | 0.93 (0.47–1.86)0.049 0.843 | 0.87 (0.28–2.67)0.009 0.804 | 0.90 (0.34–2.37)0.016 0.829 |

| SOC | |||||

| HB | 14 | 2579/2973 | 1.02 (0.86–1.22)0.012 0.787 | 1.00 (0.81–1.22)0.023 0.972 | 1.01 (0.82–1.24)0.012 0.787 |

| PB | 8 | 4357/4646 | 1.04 (0.89–1.22)0.009 0.600 | 1.04 (0.94–1.14)0.298 0.483 | 1.04 (0.95–1.14)0.199 0.425 |

| Genotyping | |||||

| Others | 5 | 977/1309 | 1.07 (0.91–1.26)0.420 0.420 | 0.97 (0.62–1.53)0.021 0.900 | 1.07 (0.79–1.45)0.079 0.668 |

| Sequencing | 2 | 546/530 | 0.94 (0.75–1.19)0.166 0.608 | 0.76 (0.34–1.70)0.055 0.505 | 0.80 (0.41–1.55)0.086 0.506 |

| TaqMan | 7 | 4456/4733 | 1.04 (0.92–1.17)0.081 0.520 | 1.02 (0.93–1.12)0.278 0.638 | 1.02 (0.93–1.12)0.152 0.672 |

| PCR-RFLP | 5 | 463/562 | 0.74 (0.43–1.28)0.030 0.280 | 0.90 (0.63–1.29)0.263 0.565 | 0.89 (0.63–1.26)0.186 0.520 |

| ARMS-PCR | 3 | 494/485 | 1.56 (0.74–3.29)0.001 0.239 | 1.28 (0.93–1.78)0.163 0.135 | 1.54 (0.80–2.97)0.024 0.192 |

| rs361525 | |||||

| Total | 8 | 2212/2222 | 0.93 (0.66–1.32)0.007 0.684 | 0.86 (0.52–1.41)0.000 0.542 | 0.85 (0.52–1.39)0.000 0.525 |

| HWE | 6 | 2043/1979 | 1.11 (0,91–1.35)0.111 0.321 | 1.02 (0,69–1.52)0.055 0.905 | 1.05 (0,73–1.52)0.803 0.794 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Asian | 3 | 450/470 | 0.72 (0.34–1.50)0.039 0.380 | 0.55 (0.15–1.99)0.002 0.360 | 0.54 (0.15–2.00)0.001 0.357 |

| Caucasian | 4 | 1698/1624 | 1.16 (0.94–1.44)0.673 0.164 | 1.16 (0.94–1.44)0.673 0.164 | 1.16 (0.94–1.44)0.673 0.164 |

| African-American | 1 | 64/126 | – | – | – |

| Genotyping | |||||

| Others | 2 | 178/188 | 0.65 (0.47–0.89)0.111 0.008 | 0.44 (0.09–2.25)0.002 0.326 | 0.44 (0.08–2.28)0.002 0.325 |

| Sequencing | 2 | 535/511 | 1.07 (0.72–1.57)0.595 0.746 | 0.90 (0.59–1.38)0.590 0.633 | 0.98 (0.65–1.48)0.999 0.936 |

| PCR-RFLP | 2 | 140/150 | 2.59 (0.98–6.85)0.628 0.055 | 2.68 (1.00–7.20)0.626 0.050 | 2.68 (1.00–7.20)0.626 0.050 |

| TaqMan | 2 | 1359/1371 | 0.77 (0.30–2.01)0.017 0.599 | 0.78 (0.28–2.20)0.011 0.640 | 0.77 (0.28–2.13)0.013 0.620 |

| rs1799724 | |||||

| Total | 5 | 2914/3121 | 0.95 (0.84–1.07)0.169 0.381 | 1.01 (0.80–1.27)0.054 0.951 | 0.95 (0.83–1.07)0.120 0.390 |

| HWE | 3 | 2444/2735 | 0.99 (0,78–1.26)0.042 0.930 | 0.98 (0,74–1.30)0.037 0.896 | 0.99 (0,75–1.30)0.032 0.931 |

| Caucasian | 3 | 2253/2493 | 0.90 (0.79–1.03)0.403 0.115 | 0.88 (0.76–1.02)0.196 0.082 | 0.88 (0.76–1.02)0.400 0.089 |

Ph: value of Q-test for heterogeneity test; P: Z-test for the statistical significance of the OR; HB hospital-based, PB population-based, SOC source of control, PCR-FLIP polymerase chain reaction and restrictive fragment length polymorphism, ARMS amplification refractory mutation system HWE, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium of control group, W wild type-allele, M mutant-allele

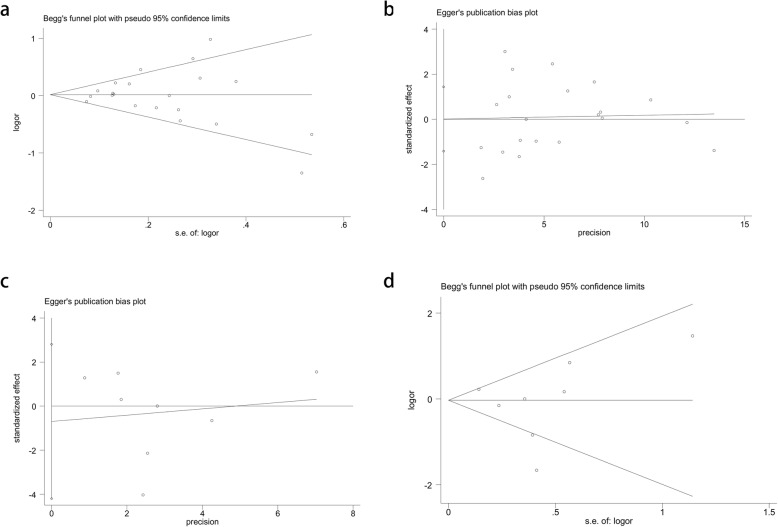

The publication bias was assessed by applying Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test. Based on the samples and publications, we tested two SNPs, rs1800629 and rs361525. The shape of the funnel plots was symmetrical, and the Egger’s test supported no existence of publication bias in any of the three comparisons for the rs1800629 (t = 0.01, p = 0.989 for Egger’s test; z = 0.21, p = 0.833 for Begg’s test, Fig. 4a, b) and rs361525 (t = − 0.3, p = 0.765 for Egger’s test; z = − 0.12, p = 1 for Begg’s test, Fig. 4c, d) polymorphisms (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Publication bias. a. Begg’s funnel plot for publication bias test (A-allele vs. G-allele). b. Egger’s publication bias plot (A-allele vs. G-allele). c. Begg’s funnel plot for publication bias test (A-allele vs. G-allele). d. Egger’s publication bias plot (A-allele vs. G-allele)

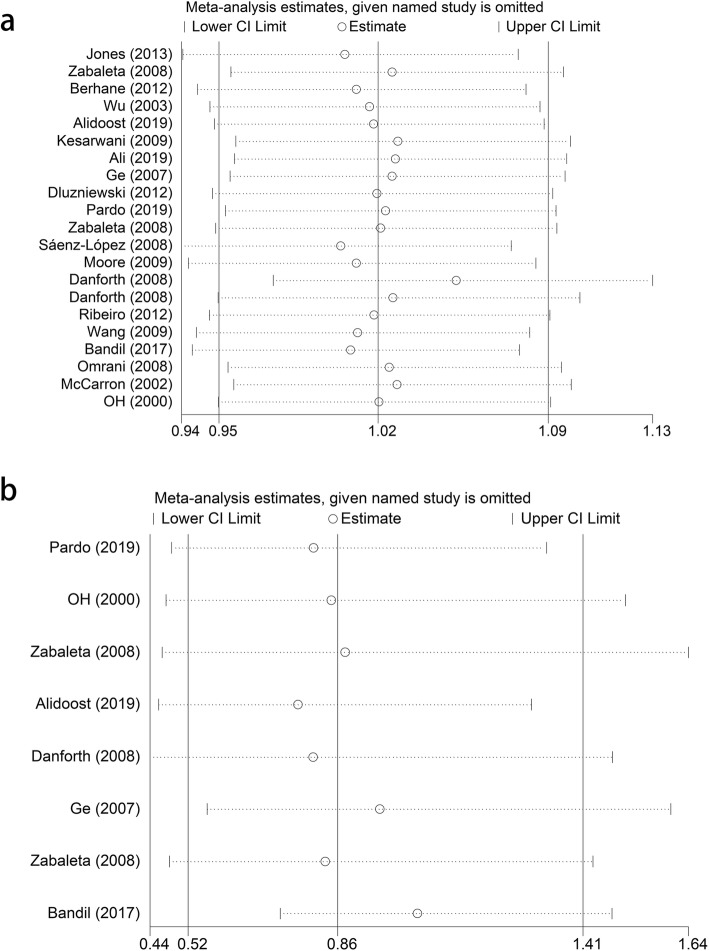

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to assess the effect of a specific publication on the overall estimate. Similar with publication bias, we also analyzed both rs1800629 and rs361525 (Fig. 5a, b), and no significant changes were observed when excluding each study in any of the three genetic models (allele, heterozygous and dominant). Thus, the final pooled results are both stable and reliable.

Fig. 5.

Sensitivity analysis. a. Sensitivity analysis for TNF-α rs1800629 polymorphism and RA risk (A-allele vs. G-allele). b. Sensitivity analysis between TNF-α rs361525 polymorphism and RA risk (A-allele vs. G-allele)

Discussion

There is evidence to suggest that chronic inflammation is prevalent in the adult prostate and may contribute to disease development in the form of promoting tumor initiation and progression [5, 41]. Therefore, chronic inflammation has been considered an enabling characteristic in the development of cancers [42], such as PCA. Several previous epidemiological studies have been explored to make a connection between inflammation and PCA development, showing evidence that associates symptomatic prostatitis with PCA risk [43–45]. For example, men with prostatitis have increased serum PSA levels, and while a medical diagnosis for prostatitis symptoms may be received initially, they may be screened for PCA and might be diagnosed with PCA in the end. Furthermore, many men with prostatic inflammation without symptoms also have increased PSA values, which may increase the odds of visits to the doctor, and they may be identified as having PCA [45]. Taken together, these observations indicate that the detection of inflammation in the prostate may be helpful for us to better identify PCA patients; however, there are no specific biomarkers of prostate inflammation to date.

Studying both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine genes is essential for PCA [21]. TNF-α, as a main mediator of inflammation, has a vital role in PCA development [10]. By considering the capacity of TNF-α promoter SNPs (rs1800629 and rs361525), and the influence of their gene expression [13, 14], these two SNPs have been identified as potential functional variants and as novel biomarkers for the early detection for PCA susceptibility.

Several studies and two meta-analyses have examined the association between TNF-α gene polymorphisms and PCA risk [15–36]. Nevertheless, the findings were inconsistent, possibly due to the small samples or relatively low statistical power of the included studies. Therefore, a current, updated meta-analysis with a comprehensive assessment that included more eligible studies was performed to evaluate the impact of TNF-α gene polymorphisms (rs1800629, rs361525 and rs1799724) on PCA susceptibility, which may overcome the aforementioned disadvantages [15, 16, 19–36]. For the TNF-α rs1800629 polymorphism, the findings from 20 studies, including 6936 cases and 7619 controls, did not support an association between this variant and PCA risk [15, 16, 19–36]. To the best of our knowledge, for the rs1799724 [15, 16, 35] polymorphism, which was analyzed for the first time, no significant association was detected from 3 studies, which included 2914 cases and 3121 controls. For the rs361525 polymorphism [15, 20, 21, 24, 28, 30, 35], pooled significant relationships were observed in the genotyping method subgroups. Cumulatively, we believe no association exists between the four common TNF-α polymorphisms and PCA risk based on the current evidence.

Despite a comprehensive analysis of the current associations between the four TNF-α polymorphisms and the risk of developing PCA, there are some limitations that should be considered. First, the number of samples remains insufficient, especially for the rs1799724 and rs1799964 polymorphisms and ethnicities in some polymorphisms, such as African-American, Asian, African and mixed populations, which perhaps leads to imbalance and publication bias. Second, gene-gene, SNP-SNP and gene-environment interactions should be taken into consideration. Other covariates, including prostate health index, age, family history, environmental factors, Gleason score, TNM stage and living habits, should be better observed, which will help us to draw an exact conclusion. Third, the protein expression level of TNF-α in different polymorphisms should also be observed and be reevaluated by meta-analysis in the future research.

In summary, our study presents evidence that three of the most common TNF-α polymorphisms (rs1800629, rs361525 and rs1799724) are not associated with PCA risk, which should be verified in the future, but they may be poised to become serum biomarkers in several subgroups for the detection of PCA susceptibility.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PCA

Prostate cancer

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- ORs

Odds ratios

- CIs

Confidence intervals

- AUC

Area under curve

- MHC III

Major histocompatibility complex

- SNPs

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- HWE

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

Authors’ contribution

TL, LY and LZ conceived the study. LZ, CY and HJ searched the databases and extracted the data. TL and HY analyzed the data. TL wrote the draft of the paper. LZ reviewed the manuscript. The author(s) read and approve the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the High-Level Medical Talents Training Project of China (NO.2016CZBJ035).

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated in the present research is contained in this manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lei Yin and Chuang Yue contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Li Zuo, Email: chenyuhuameta@sina.com.

Tao Liu, Email: renkeweijy@163.com.

References

- 1.Ferlay EM, Lam F, Colombet M. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panigrahi GK, Praharaj PP, Kittaka H, Mridha AR, Black OM, Singh R, Mercer R, van Bokhoven A, Torkko KC, Agarwal C, et al. Exosome proteomic analyses identify inflammatory phenotype and novel biomarkers in African American prostate cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2019;8(3):1110–1123. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen DP, Li J, Tewari AK. Inflammation and prostate cancer: the role of interleukin 6 (IL-6) BJU Int. 2014;113(6):986–992. doi: 10.1111/bju.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Marzo AM, Platz EA, Sutcliffe S, Xu J, Gronberg H, Drake CG, Nakai Y, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(4):256–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palapattu GS, Sutcliffe S, Bastian PJ, Platz EA, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG. Prostate carcinogenesis and inflammation: emerging insights. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(7):1170–1181. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chadha KC, Miller A, Nair BB, Schwartz SA, Trump DL, Underwood W. New serum biomarkers for prostate cancer diagnosis. Clin Cancer Investigation J. 2014;3(1):72–79. doi: 10.4103/2278-0513.125802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heidari Z, Moudi B, Mahmoudzadeh Sagheb H, Moudi M. Association of TNF-alpha gene polymorphisms with production of protein and susceptibility to chronic hepatitis B infection in the south east Iranian population. Hepat Mon. 2016;16(11):e41984. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.41984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motawi TK, El-Maraghy SA, Sharaf SA, Said SE. Association of CARD10 rs6000782 and TNF rs1799724 variants with paediatric-onset autoimmune hepatitis. J Adv Res. 2019;15:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eaton KD, Romine PE, Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, Barnett MJ, Petersdorf EW. Inflammatory gene polymorphisms in lung Cancer susceptibility. J Thoracic Oncology. 2018;13(5):649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stephens KE, Levine JD, Aouizerat BE, Paul SM, Abrams G, Conley YP, Miaskowski C. Associations between genetic and epigenetic variations in cytokine genes and mild persistent breast pain in women following breast cancer surgery. Cytokine. 2017;99:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winchester DA, Till C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Santella RM, Johnson-Pais TL, Leach RJ, Xu J, Zheng SL, Thompson IM, et al. Association between variants in genes involved in the immune response and prostate cancer risk in men randomized to the finasteride arm in the prostate Cancer prevention trial. Prostate. 2017;77(8):908–919. doi: 10.1002/pros.23346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du GH, Wang JK, Richards JR, Wang JJ. Genetic polymorphisms in tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-10 are associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;66:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei BF, Feng Z, Wei W, Chen X. Associations of TNF-alpha −238 a/G and IL-10 -1082 G/a genetic polymorphisms with the risk of NONFH in the Chinese population. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118(12):4872–4880. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danforth KN, Rodriguez C, Hayes RB, Sakoda LC, Huang WY, Yu K, Calle EE, Jacobs EJ, Chen BE, Andriole GL, et al. TNF polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk. Prostate. 2008;68(4):400–407. doi: 10.1002/pros.20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kesarwani P, Mandhani A, Mittal RD. Polymorphisms in tumor necrosis factor-a gene and prostate cancer risk in north Indian cohort. J Urol. 2009;182(6):2938–2943. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai J, Yang MY, Hou N, Li X. Association of tumor necrosis factor-alpha 308G/a polymorphism with urogenital cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Genetics Mol Res. 2015;14(4):16102–16112. doi: 10.4238/2015.December.7.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma L, Zhao J, Li T, He Y, Wang J, Xie L, Qin X, Li S. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:74. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali MS, Al-Rubae'i SHN, Ahmed NS. Association of rs1800629 tumor necrosis factor alpha polymorphism with risk of prostate tumors of Iraqi patients. Gene Rep. 2019;17:100477. doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2019.100477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alidoost S, Habibi M, Noormohammadi Z, Hosseini J, Azargashb E, Pouresmaeili F. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene rs1800629 (−308G/a) and rs361525 (−238G > a) polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk in an Iranian cohort. Hum Antibodies. 2020;28(1):65–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Bandil K, Singhal P, Dogra A, Rawal SK, Doval DC, Varshney AK, Bharadwaj M. Association of SNPs/haplotypes in promoter of TNF a and IL-10 gene together with life style factors in prostate cancer progression in Indian population. Inflammation Res. 2017;66(12):1085–1097. doi: 10.1007/s00011-017-1088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berhane N, Sobti RC, Melesse S, Mahdi SA, Kassu A. Significance of tumor necrosis factor alpha-308 (G/a) gene polymorphism in the development of prostate cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(12):11125–11130. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dluzniewski PJ, Wang MH, Zheng SL, De Marzo AM, Drake CG, Fedor HL, Partin AW, Han M, Fallin MD, Xu J, et al. Variation in IL10 and other genes involved in the immune response and in oxidation and prostate cancer recurrence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(10):1774–1782. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ge JC, Shan YX. Studies on the relationship between single nucleotide polymorphisms and susceptibility to prostate cancer in Chinese population. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones DZ, Ragin C, Kidd NC, Flores-Obando RE, Jackson M, McFarlane-Anderson N, Tulloch-Reid M, Kimbro KS, Kidd LR. The impact of genetic variants in inflammatory-related genes on prostate cancer risk among men of African descent: a case control study. Hereditary Cancer Clin Pract. 2013;11(1):19. doi: 10.1186/1897-4287-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarron SL, Edwards S, Evans PR, Gibbs R, Dearnaley DP, Dowe A, Southgate C, Easton DF, Eeles RA, Howell WM. Influence of cytokine gene polymorphisms on the development of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62(12):3369–3372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore SC, Leitzmann MF, Albanes D, Weinstein SJ, Snyder K, Virtamo J, Ahn J, Mayne ST, Yu H, Peters U, et al. Adipokine genes and prostate cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(4):869–876. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.BR OH, Sasaki M, Perinchery G, Ryu SB, Park YI, Carroll P, Dahiya R. Frequent genotype changes at −308 of the human tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter region in human uterine endometrial cancer. J Urol. 2000;163(5):1584–1587. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67683-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Omrani MD, Bazargani S, Bageri M. Interlukin-10, Interferon-γ and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Genes Variation in Prostate Cancer and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Curr Urol. 2008;2:175–180. doi: 10.1159/000209829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pardo T, Salcedo P, Quintero JM, Borjas L, Fernandez-Mestre M, Sanchez Y, Carrillo Z, Rivera S. Study of the association between the polymorphism of the TNF-alpha gene and prostate cancer. Revista alergia Mexico (Tecamachalco, Puebla, Mexico : 1993) 2019;66(2):154–162. doi: 10.29262/ram.v66i2.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ribeiro RJ, Monteiro CP, Azevedo AS, Cunha VF, Ramanakumar AV, Fraga AM, Pina FM, Lopes CM, Medeiros RM, Franco EL. Performance of an adipokine pathway-based multilocus genetic risk score for prostate cancer risk prediction. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saenz-Lopez P, Carretero R, Cozar JM, Romero JM, Canton J, Vilchez JR, Tallada M, Garrido F, Ruiz-Cabello F. Genetic polymorphisms of RANTES, IL1-a, MCP-1 and TNF-A genes in patients with prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:382. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang MH, Helzlsouer KJ, Smith MW, Hoffman-Bolton JA, Clipp SL, Grinberg V, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB, Drake CG, Shugart YY, et al. Association of IL10 and other immune response- and obesity-related genes with prostate cancer in CLUE II. Prostate. 2009;69(8):874–885. doi: 10.1002/pros.20933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu HC, Chang CH, Chen HY, Tsai FJ, Tsai JJ, Chen WC. p53 gene codon 72 polymorphism but not tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene is associated with prostate cancer. Urol Int. 2004;73(1):41–46. doi: 10.1159/000078803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zabaleta J, Lin HY, Sierra RA, Hall MC, Clark PE, Sartor OA, Hu JJ, Ochoa AC. Interactions of cytokine gene polymorphisms in prostate cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(3):573–578. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Dhakal IB, Lang NP, Kadlubar FF. Polymorphisms in inflammatory genes, plasma antioxidants, and prostate cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(9):1437–1444. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9571-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayashino Y, Noguchi Y, Fukui T. Systematic evaluation and comparison of statistical tests for publication bias. J Epidemiol. 2005;15(6):235–243. doi: 10.2188/jea.15.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Napolioni V. The relevance of checking population allele frequencies and Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium in genetic association studies: the case of SLC6A4 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in a Chinese Han Irritable Bowel Syndrome association study. Immunol Lett. 2014;162(1 Pt A):276–278. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sfanos KS, De Marzo AM. Prostate cancer and inflammation: the evidence. Histopathology. 2012;60(1):199–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dennis LK, Lynch CF, Torner JC. Epidemiologic association between prostatitis and prostate cancer. Urology. 2002;60(1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)01637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts RO, Bergstralh EJ, Bass SE, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ. Prostatitis as a risk factor for prostate cancer. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2004;15(1):93–99. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000101022.38330.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sfanos KS, Yegnasubramanian S, Nelson WG, De Marzo AM. The inflammatory microenvironment and microbiome in prostate cancer development. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15(1):11–24. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated in the present research is contained in this manuscript.