Abstract

Aims.

The association between Kawasaki disease (KD) and Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has rarely been studied. In this study, we investigated the hypothesis that KD may increase the risk of ADHD using a nationwide Taiwanese population-based claims database.

Methods.

Our study cohort consisted of patients who were diagnosed with KD between January 1997 and December 2005 (N = 651). For a comparison cohort, five age- and gender-matched control patients for every patient in the study cohort were selected using random sampling (N = 3255). The cumulative incidence of ADHD was 3.89/1000 (from 0.05 to 0.85) in this study. All subjects were tracked for 5 years from the date of cohort entry to identify whether or not they had developed ADHD. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was performed to evaluate 5-year ADHD-free survival rates.

Results.

Of all patients, 83 (2.1%) developed ADHD during the 5-year follow-up period, of whom 21 (3.2%) had KD and 62 (1.9%) were in the comparison cohort. The patients with KD seemed to be at an increased risk of developing ADHD (crude hazard ratio (HR): 1.71; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.04–2.80; p < 0.05). However, after adjusting for gender, age, asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and meningitis, the adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) of the ADHD in patients with KD showed no association with the controls (AHR: 1.59; 95% CI = 0.96–2.62; p = 0.07). We also investigated whether or not KD was a gender-dependent risk factor for ADHD, and found that male patients with KD did not have an increased risk of ADHD (AHR: 1.62; 95% CI = 0.96–2.74; p = 0.07) compared with the female patients.

Conclusions.

The findings of this population-based study suggest that patients with KD may not have an increased risk of ADHD and whether or not there is an association between KD and ADHD remains uncertain.

Key words: ADHD, Kawasaki disease, population-based study

Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is multisystemic vasculitis of unknown aetiology. It occurs globally and mainly affects children less than 5 years of age, with the highest incidence rates reported in Asia, especially in Japan, Korea and Taiwan (Wang et al. 2005; Huang et al. 2009; Kuo et al. 2012). The major clinical characteristics of KD are prolonged fever, bilateral non-purulent conjunctivitis, diffuse mucosal inflammation, polymorphous skin rash, indurative angioedema of the hands and feet, and non-suppurative cervical lymphadenopathy (Burns & Glode, 2004; Newburger et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2005). The most serious complications of KD are coronary artery lesions (Burns & Glode, 2004; Liang et al. 2009). Both genetic and environmental factors have been reported to play an important role in the prevalence of KD. Recent studies have also shown a significant association between allergic diseases and KD (Hwang et al. 2013; Kuo et al. 2013).

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common childhood and adolescent neuropsychiatric disorder, with a reported prevalence of approximately 3–10% among school-age children worldwide (Polanczyk et al. 2007), and 7.5% in Taiwan (Gau et al. 2005). The core symptoms of ADHD are inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity that have a significant negative impact on global aspects of academic performance, interpersonal relationships and family function (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Spencer et al. 2007). The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of ADHD are complex and multidimensional, and the risk factors for ADHD are generally classified as prenatal, perinatal and postnatal in origin (Galera et al. 2011; Sagiv et al. 2013). Several postnatal factors have been reported to increase the risk of ADHD in childhood, including head injury, meningitis, encephalitis, epilepsy and exposure to toxins or drugs (Millichap, 2008). A recent nationwide population-based study suggested an association between ADHD and allergic/autoimmune diseases (Chen et al. 2013), and the release of inflammatory cytokines caused by allergic/autoimmune diseases has been reported to interfere with the neurotransmitter system and brain maturation involved in the pathophysiology of ADHD (Schmitt et al. 2010). However, no study has investigated whether or not physiological abnormalities in KD (cerebral hypoperfusion and inflammation) are associated with the subsequent development of ADHD symptoms. The aim of this study was to investigate whether KD increases the risk of ADHD using a nationwide Taiwanese population-based claims database.

Methods

Database

The National Health Insurance (NHI) program was established in Taiwan in 1995. The NHI program is compulsory, and close to 99% of the population of Taiwan was enrolled by 2009. All claims data are recorded in the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) and managed by the Taiwan National Health Research Institutes (NHRI).

The NHIRD consists of comprehensive health care data for researchers, including ambulatory care records, inpatient care records, registration files, catastrophic illness files, and various data regarding drug prescriptions of the insured 23.5 million enrollees. For this study, we retrieved data from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005 (LHID2005), a subset of the NHIRD. The LHID2005 includes all original medical claims for 1 000 000 enrollees from the NHIRD from 1997 to 2010, and is publicly released to researchers. The NHRI has reported that there are no statistically significant differences in age or gender between the randomly sampled group in the LHID2005 and all beneficiaries of the NHI program. In addition, each subject's original identification number is encrypted by the NHRI to ensure privacy in the LHID2005 dataset. The encryption procedure is consistent between other datasets so that all claims data can be linked to obtain relevant medical data.

Study population

We used a study cohort and a comparison cohort to examine the relationship between KD and ADHD. The study cohort consisted of patients with KD who were under 10 years of age and newly diagnosed with KD (The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, ICD-9-CM: 446.1) between January 1997 and December 2005. The date of the initial diagnosis of KD was assigned as the index date for each KD patient. To improve data accuracy, we required that all diagnoses had an ICD-9-CM code assigned by a paediatrician. Similarly, we required that diagnoses of ADHD had an ICD-9-CM code assigned by a psychiatrist or paediatrician. Each KD cohort patient was matched based on age, gender and index year to five randomly identified beneficiaries without KD to create a comparison cohort. In this study, we defined a diagnosis of ADHD as ICD-9-CM codes 314.00 and 314.01. The patients who had a pre-existing diagnosis of ADHD before being diagnosed with KD were excluded from both cohorts. We also identified relevant comorbidities, including asthma (ICD-9-CM 493.X), allergic rhinitis (ICD-9-CM 477.X), atopic dermatitis (ICD-9-CM 691.X), head injury (ICD-9-CM 959.01), meningitis (ICD-9-CM 322.X), encephalitis (ICD-9-CM 323.X) and epilepsy (ICD-9-CM 345.X). The following relevant psychiatric disorders that are commonly comorbid with ADHD were also identified: oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder (ICD-9-CM 313.81 or 312.X), autistic spectrum disorder (ICD-9-CM 299.X), tic disorder (ICD-9-CM 307.2X) and intellectual disability (ICD-9-CM 317 to 319).

Level of urbanisation

To classify the level of urbanisation, all 365 townships in Taiwan were stratified into seven levels according to the standards established by the Taiwanese NHRI based on cluster analysis of the 2000 Taiwan census data, with 1 referring to the most urbanised and 7 referring to the least urbanised. The criteria on which these strata were determined included population density (persons/km2), the number of physicians per 100 000 people, the percentage of people with a college education, the percentage of people over 65 years of age, and the percentage of agricultural workers. Because levels 4, 5, 6 and 7 contained few KD cases, they were combined into a single group and referred to as level 4.

Statistical analysis

All data processing and statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS version 8.2 (SAS System for Windows, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Pearson X2 tests were used to compare differences in geographic location and urbanisation level of the patients’ residence between the study and comparison groups. We also performed survival analysis using the Kaplan–Meier method, and used the log-rank test to compare survival distribution between the cohorts. The survival period was calculated for the patients who suffered from KD until ADHD was diagnosed in the outpatient records or discharge codes from the hospitalisation records, or the end of the study period (December 31, 2010), whichever came first. After adjusting for urbanisation level, region and comorbidities as potential confounders, we performed Cox proportional hazards analysis stratified by gender, age group and index year to investigate the risk of ADHD during the 5-year follow-up period in both cohorts. We further classified gender and age group risk factors in both groups. We also stratified analysis of the underlying status of allergic diseases and meningitis to assess the association between KD and ADHD events. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs were calculated to quantify the risk of ADHD. The results of the comparisons with a two-sided p value of less than 0.05 were considered to represent statistically significant differences.

Ethical approval

The insurance reimbursement claims used in this study came from the NHIRD, which is made available for research purposes. This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. This study was also evaluated and approved by the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital's Institutional Review Board (IRB No.:102-0364B). Informed consent was not obtained and patient records/information was anonymised and de-identified prior to analysis.

Results

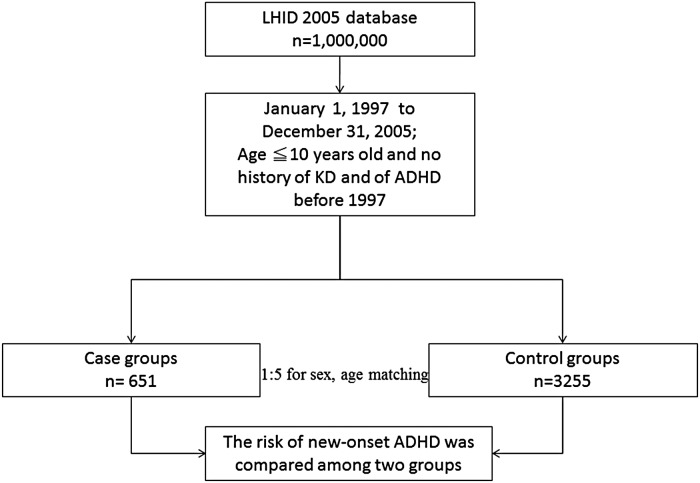

The research design of this study is shown in Fig. 1. The KD cohort contained 651 patients, and 3255 patients were included in the comparison cohort. The distribution of demographic characteristics and the comorbidities for the two cohorts are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in urbanisation level, geographic region, head injury, epilepsy or encephalitis (all p > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the selection of the study and control subjects from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the selected patients, stratified by the presence/absence of Kawasaki disease (KD) from 1997 to 2005 (n = 3906)

| Patients with KD (n = 651) | Patients without KD (n = 3255) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | N | % | p value* | |

| Gender | 1 | ||||

| Male | 391 | 60.1 | 1955 | 60.1 | |

| Female | 260 | 39.9 | 1300 | 39.9 | |

| Age (years) | 1 | ||||

| 0–5 | 562 | 86.3 | 2810 | 86.3 | |

| 6–10 | 89 | 13.7 | 445 | 13.7 | |

| Follow-up, years, mean (s.d.) | 0.05 | ||||

| 4.93 | (0.48) | 4.97 | (0.31) | ||

| Urbanisation level | 0.13 | ||||

| 1 (most urbanised) | 213 | 32.7 | 1093 | 33.6 | |

| 2 | 194 | 29.8 | 830 | 25.5 | |

| 3 | 107 | 16.5 | 572 | 17.6 | |

| 4 (least urbanised) | 137 | 21.0 | 760 | 23.3 | |

| Geographic region | 0.09 | ||||

| North | 324 | 49.8 | 1555 | 47.8 | |

| Central | 188 | 28.9 | 868 | 26.7 | |

| South | 119 | 18.3 | 687 | 20.8 | |

| Eastern | 20 | 3.0 | 154 | 4.7 | |

| Asthma | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 327 | 50.2 | 1184 | 36.4 | |

| No | 324 | 49.8 | 2071 | 63.6 | |

| Allergic rhinitis | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 484 | 74.3 | 2013 | 61.8 | |

| No | 167 | 25.7 | 1242 | 38.2 | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 491 | 75.4 | 2295 | 70.5 | |

| No | 160 | 24.6 | 960 | 29.5 | |

| Head injury | 0.14 | ||||

| Yes | 24 | 3.7 | 86 | 2.6 | |

| No | 627 | 96.3 | 3169 | 97.4 | |

| Meningitis | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 15 | 2.3 | 19 | 0.6 | |

| No | 636 | 97.7 | 3236 | 99.4 | |

| Encephalitis | 0.63 | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 0.5 | 11 | 0.3 | |

| No | 648 | 99.5 | 3244 | 99.7 | |

| Epilepsy | 0.63 | ||||

| Yes | 13 | 2.0 | 75 | 2.3 | |

| No | 638 | 98.0 | 3180 | 97.7 | |

s.d.: standard deviation.

p value according to the chi square test; follow-up years test by T-Test.

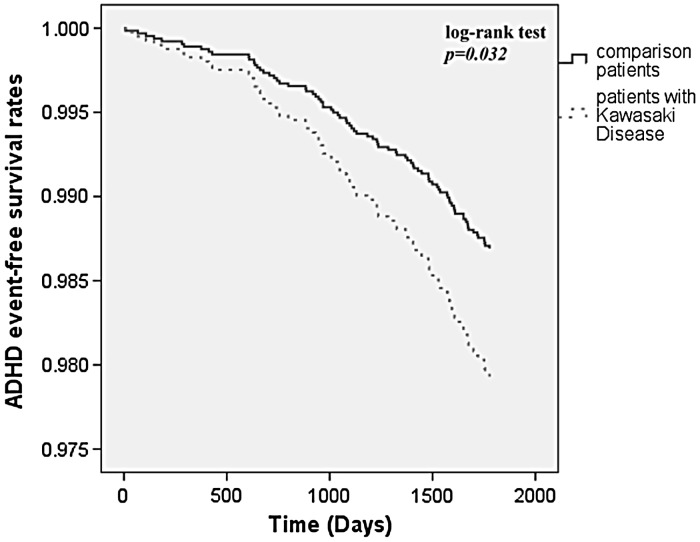

In total, 83 patients were diagnosed with ADHD during the 5-year follow-up period, including 21 KD patients (3.2%) and 62 patients in the comparison cohort (1.9%). Kaplan–Meier survival curves demonstrated a significantly lower ADHD-free survival rate in the KD cohort compared with the comparison cohort (log-rank test, p = 0.032) (Fig. 2). The overall incidence rate was higher in the KD cohort (6.54 per 1000 patient–years) than in the comparison cohort (3.83 per 1000 patient–years).

Fig. 2.

ADHD-free survival rates for the patients with Kawasaki disease and comparison cohort from 1997 to 2005. (Kaplan–Meier survival curves).

Cox regression analysis showed that the crude HR (CHR) of ADHD was 1.71 times greater for the KD patients (CHR: 1.71; 95% CI = 1.04–2.80; p < 0.05) than for the comparison patients. After adjusting for potential confounders including asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and meningitis, KD was associated with a 1.59 times greater risk of ADHD (adjusted HR (AHR): 1.59; 95% CI = 0.96–2.62; p > 0.05) compared with the patients without KD, but the difference did not reach significance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios (HRs) of ADHD among the Kawasaki disease (KD) patients during the 5-year follow-up period from the index ambulatory visit or inpatient care from 1997 to 2005

| Total (n = 3906) | Patients with KD (n = 651) | Patients without KD (n = 3255) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development of ADHD | (%) | (%) | (%) |

| 5-year follow-up period | |||

| Yes (%) | 2.1 | 3.2 | 1.9 |

| No (%) | 97.9 | 96.8 | 98.1 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1.71 (1.04–2.80)* | 1 (ref) | |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1.59 (0.96–2.62) | 1 (ref) |

Total sample number = 3906.

Both crude and adjusted HRs were calculated by Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, and stratified by age and gender.

Adjustments were made for gender, age, asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and meningitis.

Indicates p < 0.05.

After adjusting for potential confounders including gender, age, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, autistic spectrum disorder, tic disorder and intellectual disability, the KD patients did not have a higher risk of developing ADHD (AHR: 1.64; 95% CI = 0.99–2.69; p = 0.06) than the comparison cohort.

We further investigated whether KD was a time-dependent risk factor for ADHD, and divided the KD patients into three groups according to follow-up period. For 1 year of follow-up and 3 years of follow-up, there were no statistical significances between the KD patients and comparison cohort (Table 3). In gender-stratified analysis, the male subjects (AHR: 1.62; 95% CI = 0.96–2.74; p = 0.07) did not have a higher risk of developing ADHD than the female subjects (AHR: 1.32; 95% CI = 0.26–6.68; p = 0.74) (Table 4).

Table 3.

1-year, 3-year and 5-year follow-up periods

| 1-year follow-up period | 3-year follow-up period | 5-year follow-up period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development of ADHD | Patients with Kawasaki disease (KD) (n = 651) | Patients without KD (n = 3255) | Patients with KD (n = 651) | Patients without KD (n = 3255) | Patients with KD (n = 651) | Patients without KD (n = 3255) |

| Yes (%) | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 1.9 |

| No (%) | 99.5 | 99.9 | 98.5 | 99.2 | 96.8 | 98.1 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 3.76 (0.84–16.80) | 1 (ref) | 1.93 (0.93–4.01) | 1 (ref) | 1.71 (1.04–2.80)* | 1 (ref) |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 3.74 (0.81–17.18) | 1 (ref) | 1.86 (089–3.89) | 1 (ref) | 1.59 (0.96–2.62) | 1 (ref) |

Total sample number = 3906.

Both crude and adjusted HRs were calculated by Cox proportional hazard analysis, and stratified by age and gender.

Adjustments were made for gender, age, asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and meningitis.

Indicates p < 0.05.

Table 4.

Hazard ratios for ADHD among the patients with Kawasaki disease (KD) and the comparison cohort by gender

| Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||

| Patients with KD (n = 260) | Patients without KD (n = 1300) | Patients with KD (n = 391) | Patients without KD (n = 1955) | |

| Development of ADHD | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) |

| Yes | 0.8 | 0.5 | 4.9 | 2.9 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1.68 (0.34–8.31) | 1 (ref) | 1.72 (1.02–2.89)* | 1 (ref) |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1.32 (0.26–6.68) | 1 (ref) | 1.62 (0.96–2.74) | 1 (ref) |

Adjustments were made for patients’ Age, Asthma, Allergic rhinitis, Atopic dermatitis and Meningitis.

Indicates p < 0.05.

Discussion

KD has been reported to be associated with an increased risk of allergic diseases including allergic rhinitis, asthma and atopic dermatitis (Hwang et al. 2013; Kuo et al. 2013; Tsai et al. 2013b). A T helper 2 (Th2) immune response leading to higher levels of IL-4, IL-5, CCL17, IL-21, eosinophils and IgE in patients with KD and may be a key factor contributing to the risk of allergic diseases (Burns et al. 2005; Kuo et al. 2007, 2009; Weng et al. 2010; Bae et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2013). The increase in the prevalence and burden of allergic diseases including atopic dermatitis, rhinitis and asthma over the past decades has been paralleled by a worldwide increase in the prevalence of ADHD, and an association between ADHD and atopic diseases has been reported in several studies (Hak et al. 2013; Tsai et al. 2013a). Schmitt et al. (2010) reviewed 20 articles in the related literature and concluded that eczema appears to be independently related to ADHD, but not atopic diseases in general. A dose-dependent relationship has also been reported between the prevalence of mental health disorders and the severity of allergic skin disease (Yaghmaie et al. 2013). Allergic diseases and a Th2 immune response may therefore be key factors in the association between ADHD and KD.

The results of the current study demonstrated that the KD patients were not associated with a greater risk of developing ADHD compared with patients without KD. The most well-known neurobiological hypotheses for the aetiology of ADHD are the dysregulation of catecholaminergic circuits in the brain, particularly in the prefrontal cortex (Arnsten & Pliszka, 2011). In addition, decreased cerebral blood flow in the right lateral prefrontal cortex, right middle temporal cortex and both orbital prefrontal cortices has been reported in patients with ADHD (Kim et al. 2002). Furthermore, increased levels of inflammatory cytokines have been proposed to interfere with neurodevelopment in ADHD-relevant brain areas and the neurotransmitter system involved in the pathology of ADHD (Buske-Kirschbaum et al. 2013). KD is characterised by multisystemic vasculitis, and approximately 1–30% of patients with KD exhibit central nervous system involvement (Hikita et al. 2011). Taken together, the physiological abnormalities in children with KD may have an impact on blood perfusion and inflammatory changes in the brain, and increase the risk of exhibiting ADHD psychopathology. Nevertheless, KD is a chronic illness, and patients with KD require regular follow-up at hospital. Therefore, the families of these patients may have greater access to medical information and as a result a greater awareness about their child's health condition than the families of patients without KD. Therefore, children with KD may be more likely to be treated by child psychiatrists and diagnosed as having ADHD.

We found that KD did not appear to be a time-dependent risk factor for ADHD, and the risk was not increased after 5 years of follow-up. In addition, male subjects (who accounted for the majority of cases) did not have a higher risk of developing ADHD compared with female subjects. Hikita et al. (2011) reported that the occurrence of localised hypoperfusion and neurological sequelae may not only be restricted to the acute phase in KD, but that they may also occur from 3 years after disease onset. This implies that the relatively minor influence of KD on cerebral blood flow and inflammation may cumulate gradually and eventually lead to the presentation of neuropsychiatric symptoms over the long term. Another possible explanation for this phenomenon may be associated with the peak age of a diagnosis of ADHD. The confirmation of a diagnosis of ADHD can be difficult in preschool age children. A previous epidemiological study showed that most patients with ADHD are diagnosed between the ages of 6 to 8 years (Chen et al. 2011). Therefore, patients with KD should be assessed for ADHD more than 5 years after disease onset. In terms of gender differences, we found that the male patients with KD did not have a higher risk of developing ADHD than the female subjects. The gender difference in the risk of developing ADHD may be attributable to discrepant levels of KD-related central nervous system involvement. However, this finding should be viewed cautiously as the number of female ADHD patients was very small. Compelling evidence has indicated that ADHD is more prevalent in boys than in girls, with the ratio ranging from 4 to 1 to as high as 9 to 1 (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Gau et al. 2005; Polanczyk et al. 2007). Therefore, the male predominance of patients with ADHD in this study was probably influenced by the male predominance of KD. Further studies are warranted to examine whether a gender difference in the risk of developing ADHD is related to a variety in statistical power or to an actual gender differences in KD-induced neuropsychiatric symptoms.

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, environmental and genetic risk factors which could affect the susceptibility to ADHD were not included in our analysis. Second, household income and economic status could be important factors for the evaluation of access and utilisation of medical care, and these factors were not included in our analysis. Third, because ADHD is possibly related to an inflammatory response, the KD patients with coronary aneurysms should have had a higher rate of ADHD. The influence of coronary aneurysms on the risk of ADHD warrants further investigation. Last, this study used reimbursement data, and the diagnoses of KD and ADHD in our cohort relied solely on ICD codes of NHI claims records instead of an active survey or structural interview. A structural diagnostic instrument should be used to validate the diagnoses of KD and ADHD in future studies.

In conclusion, the results of our population-based study suggest that patients with KD did not have an increased risk of ADHD. However, a clinical cohort study using research diagnostic criteria of KD and ADHD is needed to confirm this finding.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This study was partly supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 102-2314-B-182-053-MY3, MOST 103-2410-H-264-004) and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPG8C1082, CMRPG8B0212, CMRPG8D1561 and CMRPG8D0521). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Others: This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health and managed by the National Health Research Institutes. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health or National Health Research Institutes.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Author's Contribution

Ho-Chang Kuo conceptualised and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Wei-Chiao Chang, Liang-Jen Wang, Sung-Chou Li: carried out the initial analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Wei-Pin Chang designed the data collection instruments, and coordinated and supervised data collection at two of the four sites, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Pliszka SR (2011). Catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical function: relevance to treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and related disorders. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 99, 211–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YJ, Kim MH, Lee HY, Uh Y, Namgoong MK, Cha BH, Chun JK (2012). Elevated serum levels of IL-21 in Kawasaki disease. Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Research 4, 351–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JC, Glode MP (2004). Kawasaki syndrome. Lancet 364, 533–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JC, Shimizu C, Shike H, Newburger JW, Sundel RP, Baker AL, Matsubara T, Ishikawa Y, Brophy VA, Cheng S, Grow MA, Steiner LL, Kono N, Cantor RM (2005). Family-based association analysis implicates IL-4 in susceptibility to Kawasaki disease. Genes and Immunity 6, 438–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buske-Kirschbaum A, Schmitt J, Plessow F, Romanos M, Weidinger S, Roessner V (2013). Psychoendocrine and psychoneuroimmunological mechanisms in the comorbidity of atopic eczema and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38, 12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Yeh HH, Chen KH, Chang IS, Wu EC, Lin KM (2011). Differential effects of predictors on methylphenidate initiation and discontinuation among young people with newly diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 21, 265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MH, Su TP, Chen YS, Hsu JW, Huang KL, Chang WH, Chen TJ, Bai YM (2013). Comorbidity of allergic and autoimmune diseases among patients With ADHD: a nationwide population-based study. Journal of Attention Disorders. doi: 10.1177/1087054712474686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galera C, Cote SM, Bouvard MP, Pingault JB, Melchior M, Michel G, Boivin M, Tremblay RE (2011). Early risk factors for hyperactivity-impulsivity and inattention trajectories from age 17 months to 8 years. Archives of General Psychiatry 68, 1267–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SS, Chong MY, Chen TH, Cheng AT (2005). A 3-year panel study of mental disorders among adolescents in Taiwan. American Journal of Psychiatry 162, 1344–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hak E, de Vries TW, Hoekstra PJ, Jick SS (2013). Association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with atopic diseases and skin infections? A matched case-control study using the General Practice Research Database. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 111, 102–106 e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikita T, Kaminaga T, Wakita S, Ogita K, Ikemoto H, Fujii Y, Oba H, Yanagawa Y (2011). Regional cerebral blood flow abnormalities in patients with Kawasaki disease. Clinical Nuclear Medicine 36, 643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WC, Huang LM, Chang IS, Chang LY, Chiang BL, Chen PJ, Wu MH, Lue HC, Lee CY (2009). Epidemiologic features of Kawasaki disease in Taiwan, 2003–2006. Pediatrics 123, e401–e405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang CY, Hwang YY, Chen YJ, Chen CC, Lin MW, Chen TJ, Lee DD, Chang YT, Wang WJ, Liu HN (2013). Atopic diathesis in patients with kawasaki disease. The Journal of Pediatrics 163, 811–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BN, Lee JS, Shin MS, Cho SC, Lee DS (2002). Regional cerebral perfusion abnormalities in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Statistical parametric mapping analysis. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 252, 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo HC, Yang KD, Liang CD, Bong CN, Yu HR, Wang L, Wang CL (2007). The relationship of eosinophilia to intravenous immunoglobulin treatment failure in Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 18, 354–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo HC, Wang CL, Liang CD, Yu HR, Huang CF, Wang L, Hwang KP, Yang KD (2009). Association of lower eosinophil-related T helper 2 (Th2) cytokines with coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 20, 266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo HC, Yang KD, Chang WC, Ger LP, Hsieh KS (2012). Kawasaki disease: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Pediatrics and Neonatology 53, 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo HC, Chang WC, Yang KD, Yu HR, Wang CL, Ho SC, Yang CY (2013). Kawasaki disease and subsequent risk of allergic diseases: a population-based matched cohort study. BMC Pediatrics 13, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CP, Huang YH, Hsu YW, Yang KD, Chien HC, Yu HR, Yang YL, Wang CL, Chang WC, Kuo HC (2013). TARC/CCL17 gene polymorphisms and expression associated with susceptibility and coronary artery aneurysm formation in Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Research 74, 545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang CD, Kuo HC, Yang KD, Wang CL, Ko SF (2009). Coronary artery fistula associated with Kawasaki disease. American Heart Journal 157, 584–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millichap JG (2008). Etiologic classification of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 121, e358–e365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, Gewitz MH, Tani LY, Burns JC, Shulman ST, Bolger AF, Ferrieri P, Baltimore RS, Wilson WR, Baddour LM, Levison ME, Pallasch TJ, Falace DA, Taubert KA (2004). Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation 110, 2747–2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA (2007). The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 164, 942–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagiv SK, Epstein JN, Bellinger DC, Korrick SA (2013). Pre- and postnatal risk factors for ADHD in a nonclinical pediatric population. Journal of Attention Disorders 17, 47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt J, Buske-Kirschbaum A, Roessner V (2010). Is atopic disease a risk factor for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? A systematic review. Allergy 65, 1506–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Mick E (2007). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 32, 631–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JD, Chang SN, Mou CH, Sung FC, Lue KH (2013a). Association between atopic diseases and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood: a population-based case-control study. Annals of Epidemiology 23, 185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai YJ, Lin CH, Fu LS, Fu YC, Lin MC, Jan SL (2013b). The association between Kawasaki disease and allergic diseases, from infancy to school age. Allergy and Asthma Proceedings 34, 467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CL, Wu YT, Liu CA, Kuo HC, Yang KD (2005). Kawasaki disease: infection, immunity and genetics. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 24, 998–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang W, Gong F, Fu S, Zhang Q, Hu J, Qi Y, Xie C, Zhang Y (2013). Evaluation of intravenous immunoglobulin resistance and coronary artery lesions in relation to Th1/Th2 cytokine profiles in patients with Kawasaki disease. Arthritis and Rheumatology 65, 805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng KP, Ho TY, Chiao YH, Cheng JT, Hsieh KS, Huang SH, Ou SF, Liu KH, Hsu CJ, Lu PJ, Hsiao M, Ger LP (2010). Cytokine genetic polymorphisms and susceptibility to Kawasaki disease in Taiwanese children. Circulation Journal 74, 2726–2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghmaie P, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL (2013). Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 131, 428–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]