Abstract

Due to the high oxidation potential between AuI and AuIII, gold redox catalysis requires at least stoichiometric amounts of a strong oxidant. We herein report the first example of an electrochemical approach in promoting gold-catalyzed oxidative coupling of terminal alkynes. Oxidation of AuI to AuIII was successfully achieved through anode oxidation, which enabled facile access to either symmetrical or unsymmetrical conjugated diynes through homo-coupling or cross-coupling. This report extends the reaction scope of this transformation to substrates that are not compatible with strong chemical oxidants and potentiates the versatility of gold redox chemistry through the utilization of electrochemical oxidative conditions.

Keywords: 1,3-diynes; electrochemistry; gold; oxidative coupling; redox catalysis

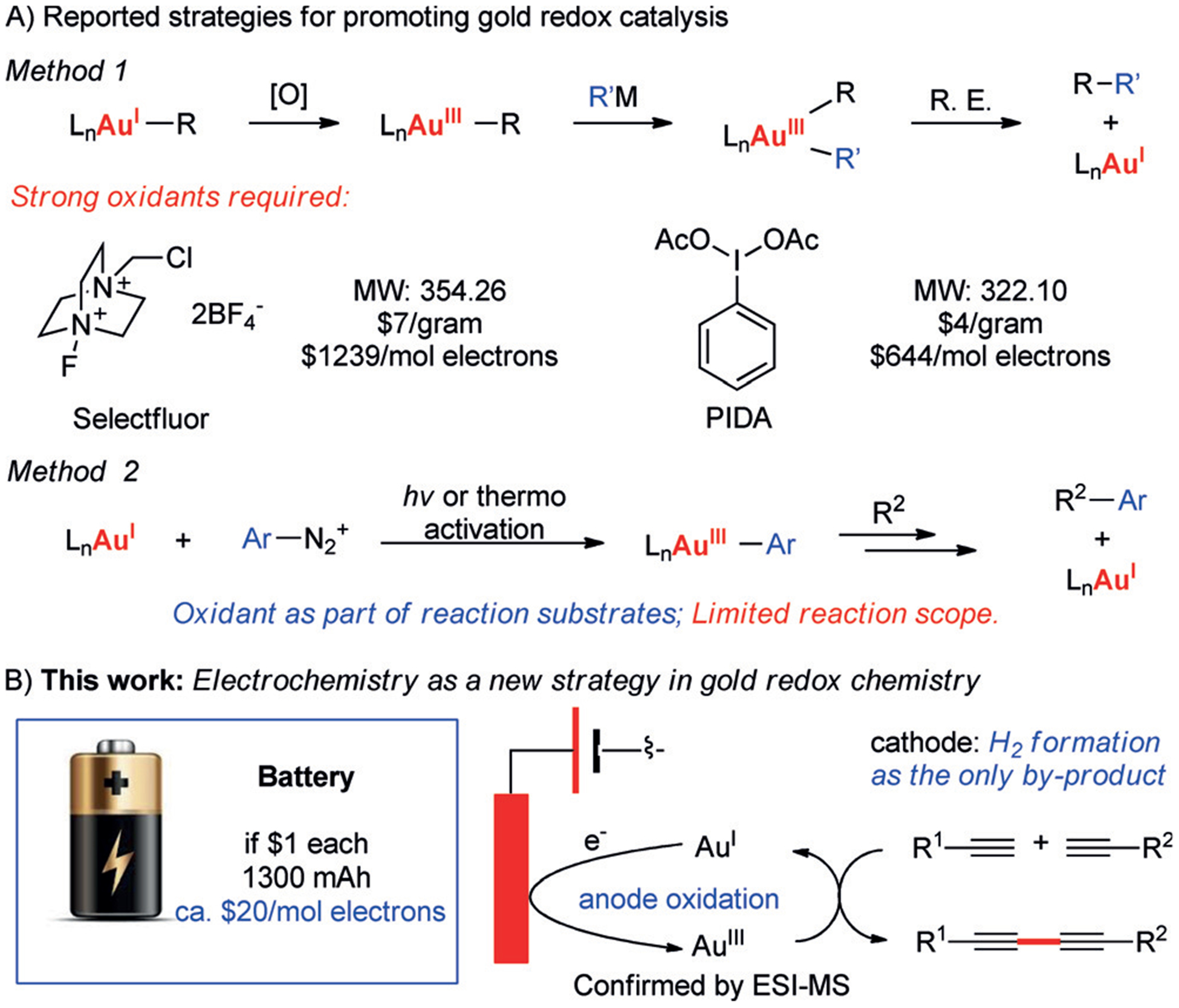

Homogeneous gold catalysis has flourished during the past two decades.[1] As a superior π-acid for C-C multiple bond activation, AuI catalysts have been applied as a powerful tool towards various transformations to rapidly build up molecular complexity.[2] Gold redox chemistry is also attractive because it presents an alternative coupling approach.[3] However, this branch of gold catalysis has been significantly less explored, largely due to the high oxidation potential of AuI/AuIII redox couple (+ 1.40 V).[4] More recently, a series of breakthroughs have been reported in this new direction for gold catalysis with/without external oxidants for AuI/AuIII oxidation (Scheme 1A).[5,6] Despite the significance of these foundational studies, there are still severe limitations. This includes the involvement of stoichiometric amounts of strong oxidants, which usually are expensive, demonstrate low atom economy, and exhibit poor functional-group compatibility. Therefore, a new efficient, practical, and recyclable system for AuI/AuIII redox catalysis is eminently desirable. Synthetic organic electrochemistry has received tremendous attention over the past several years for facilitating redox chemistry without the need for external oxidants/reductants.[7] In particular, electrochemical anodic oxidation is more attractive since it serves as an environmentally friendly and sustainable alternative oxidation strategy.[8] Recent works have demonstrated its capability to promote the challenging oxidation of transition-metal cations to their higher oxidation states, such as PdII/IV or CoI/II/III oxidation.[9] Another advantage of electrochemical oxidation is the controllable cell potential (Ecell), which allows fine-tuning of transition-metal redox processes for optimal reactivity. Considering these advantages, we set out to explore the possibility of achieving gold redox catalysis under electrochemical conditions to overcome the high oxidation potential between AuI and AuIII. Herein, we report the first example of electrochemical gold redox catalysis that dose not require any external oxidant (Scheme 1B).

Scheme 1.

Electrochemical approach for gold redox catalysis.

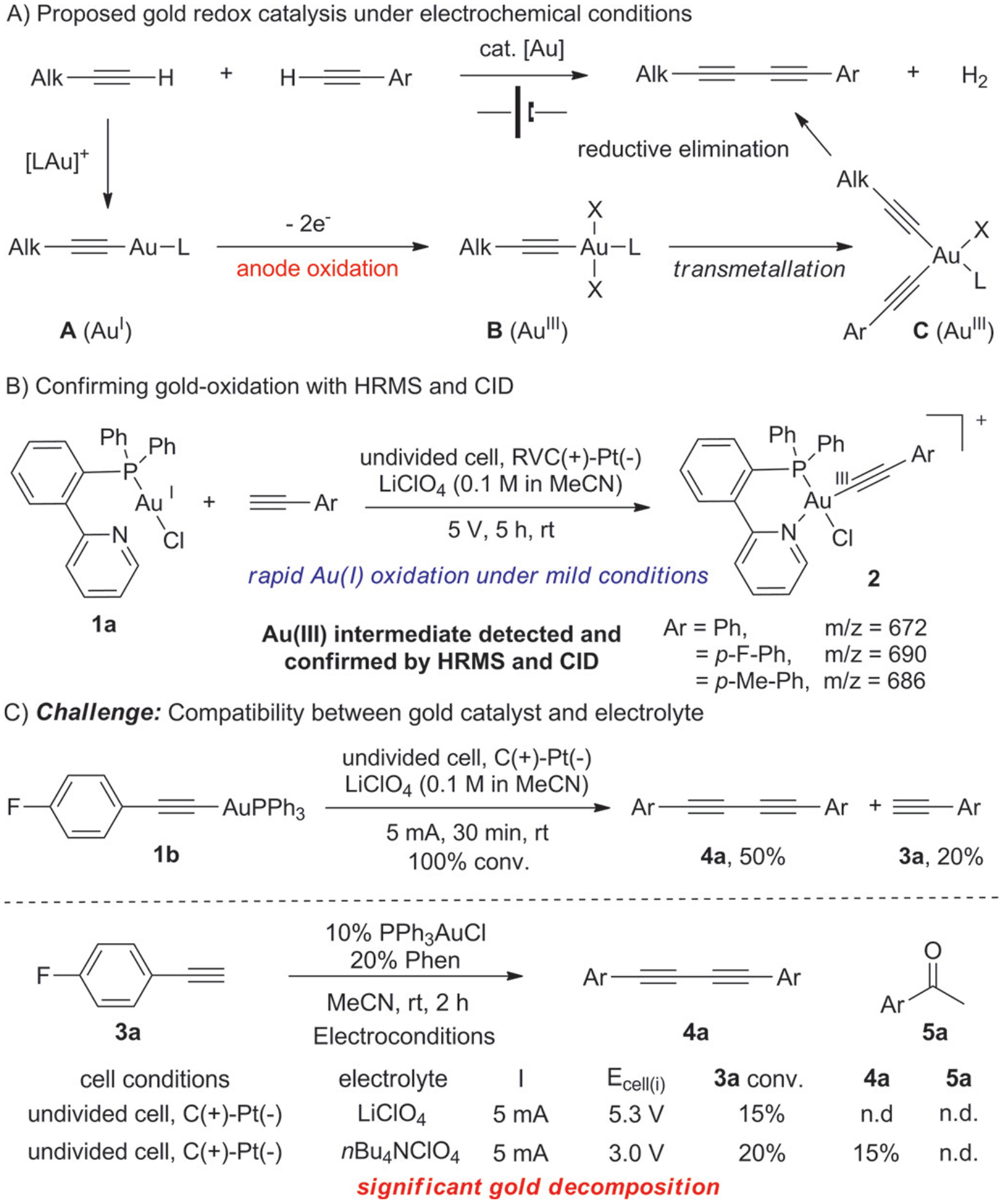

We initiated our investigation with the oxidative coupling of terminal alkynes for the synthesis of conjugated 1,3-diynes (Figure 1A).[10] This transformation is ideal for exploring electrochemical gold redox catalysis since the net reaction is the formation of diyne and H2, which is well-suited for both anode oxidation and cathode reduction.[11] To verify whether the anode oxidation concept is viable, we first prepared AuI pyridine complex 1a and charged it into typical electrochemical conditions (Figure 1B). To our delight, with the presence of alkyne, the corresponding AuIII complexes 2 were detected and confirmed by HRMS/CID within 30 minutes. This promising result showed the feasibility of achieving gold redox chemistry under electrochemical conditions (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Exploring gold-catalyzed alkyne oxidative coupling.

Encouraged by this result, we turned our attention to a catalytic version of this reaction. When charging alkyne 3a with 10% Ph3PAuCl and 20% Phen under electrochemical conditions (LiClO4 as electrolyte, undivided cell), the initial potential is ca. 5.3 V with a constant current at 5 mA. However, the conversion of 3a was very low with no desired diyne 4a observed, which could be caused by rapid metal cation reduction (Li+ and Au+) as evidenced by the formation of dark precipitate on the cathode within 10 minutes. This illustrates the challenges associated with electrochemical gold catalysis. Switching to nBu4NClO4 electrolyte slowed down the gold cation reduction on cathode, and desired product 4a was formed, even though the conversion is low.

The stoichiometric reaction of gold acetylide in Figure 1C suggest that both transmetalation and reductive elimination occurred smoothly to yield the desired diyne product 4a, despite the presence of Li+ causing significant AuI acetylide decomposition (formation of 3a). Therefore, we believed that the poor performance for the catalytic reaction must result from the sluggish formation of AuI acetylide. We speculated that the introduction of a protic solvent, which we originally thought it disadvantageous for the hydration,[12] would be beneficial for this process. By increasing proton concentration for H+ reduction on the cathode, gold catalyst decomposition can be prevented effectively, and the resulting HOX/OX buffer system will further assist the formation of gold acetylide. To verify this hypothesis, combination of CH3CN with protic solvents, including MeOH, HOAc, and TFA, was tested. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Optimal conditions for gold redox catalysis.[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Variation from “standard conditions” | 3 a conv.[b] | 4a[b] |

| 1 | none | 100% | 95% |

| 2 | MeOH instead of HOAc | 56% | 36% |

| 3 | TFA instead of HOAc | 20% | < 5% |

| 4 | LiClO4 or LiOAc as electrolyte | 10% | trace |

| 5 | nBu4NBF4, or nBu4NPF6 as electrolyte | 10% | trace |

| 6 | PPh3AuNTf2 | 100% | 91% |

| 7 | PPh3AuCl | 100% | 90% |

| 8 | No Phen | 50% | 45% |

| 9 | No HOAc | 10% | trace |

| 10 | Pt as anode | 50% | 30% |

| 11 | C as cathode | 24% | 20% |

| 12 | 3 mA (1.7–1.8 V) | 20% | 17% |

| 13 | 7 mA (3.0–3.1 V) | 100% | 60% |

| 14 | Constant V at 2 V | 68% | 64% |

| 15 | No Au | – | n.r. |

| 16 | No Current | – | n.r. |

Conditions: 3a (0.5 mmol), Au cat. (7.5 mol%), Phen (30 mol%), and electrolyte (0.5m, MeCN/HOAc =4:1, 5 mL), 2.2 Fmol−1.

19F NMR yields using benzotrifluoride as an internal standard.

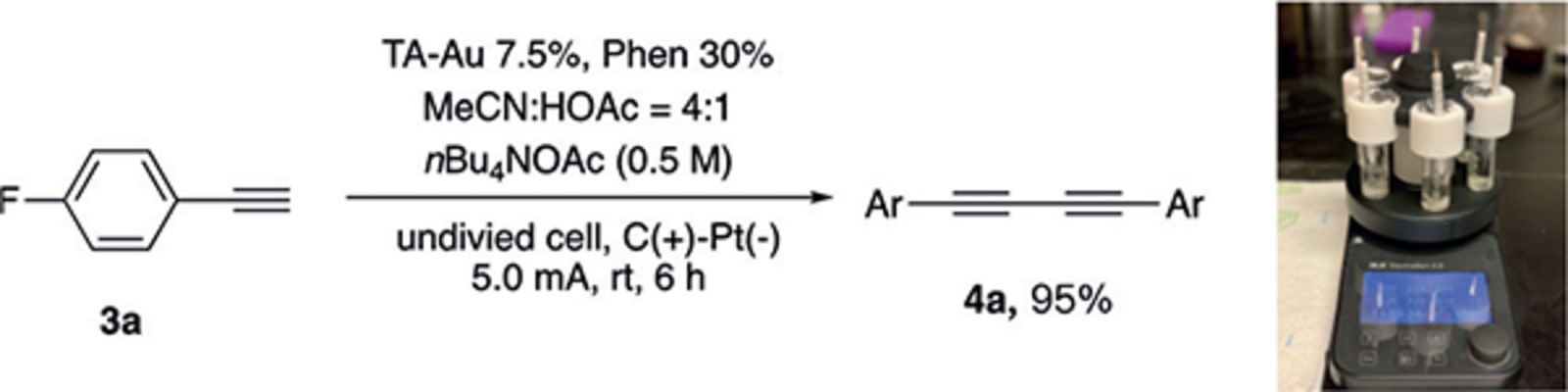

To our delight, the comprehensive condition screening revealed 0.5m nBu4NOAc in CH3CN/HOAc = 4:1 as the optimal solvent system, giving diyne 4a in excellent yields (95%, entry 1). Using methanol as a co-solvent resulted in incomplete conversion and lower yield (36%). This is likely due to the weak acidity (pKa = 16), which slows down the H2 reduction, and the resulting strong counter base that attacks the alkyne (entry 2). Interestingly, combination of CH3CN and TFA did not yield any products despite increased acidity. A dark purple color appeared quickly in the reaction system, indicating gold decomposition or TFA oxidation (entry 3). Notably, no hydration product 5a was observed when either protic solvent was present, which highlights the excellent chemoselectivity of this electrochemical approach. Furthermore, gold reduction on the cathode was not observed within the first 2 hours, thus indicating that fast gold acetylide formation is crucial to prevent gold reduction prior to H+ reduction. Additionally, nBu4NOAc has two different functions. The nBu4N+ cation is necessary to prevent the induction of fast gold decomposition (entry 4). On the other hand, OAc− anions could presumably serve as a weak conjugated base to facilitate gold acetylide formation because switching to other anions such as BF4− and PF6− could not promote this reaction (entry 5). Both PPh3AuNTf2 and PPh3AuCl are suitable catalysts for this condition. However, the optimal result was observed with gold 1,2,3-triazole complexes (TAAu), likely due to improved gold complex stability.[13] Similar to the case involving chemical oxidation, the Phen ligand is crucial, and significantly lower yields were observed without addition of Phen (entry 8). Low conversion and yield were observed when switching the electrode to other materials. This might be due to 1) the large surface area of the graphite anode for gold contact, 2) favorable H2 evolution on a Pt surface. Under the optimal conditions (constant 5 mA current), the overall potential was maintained between 2.0–2.8 V depending on the substrate. Reducing the current to 3 mA caused poor conversion due to the potential for an efficient oxidation. In contrast, raising the current to 7 mA caused a diminished yield of diyne 4a to 60%, albeit with 100% 3a conversion due to decomposition of product/gold under a higher voltage (ca. 3.5 V). Overall, we successfully developed efficient and robust reaction conditions to accomplish gold redox catalysis under electrochemical settings. With the optimal conditions revealed, we then tested homo-coupling reaction of various alkynes as shown in Table 2.

Table 2:

|

General reaction conditions: alkyne (0.5 mmol), TA-Au (7.5 mol%), and Phen (30 mol%) was added into 0.5m nBu4NOAc in MeCN:-HOAc=4:1, 5 mL. The mixture was performed under constant current (5 mA) at r.t.

Yield of isolated product.

TAAu (10 mol%), Phen (50 mol%).

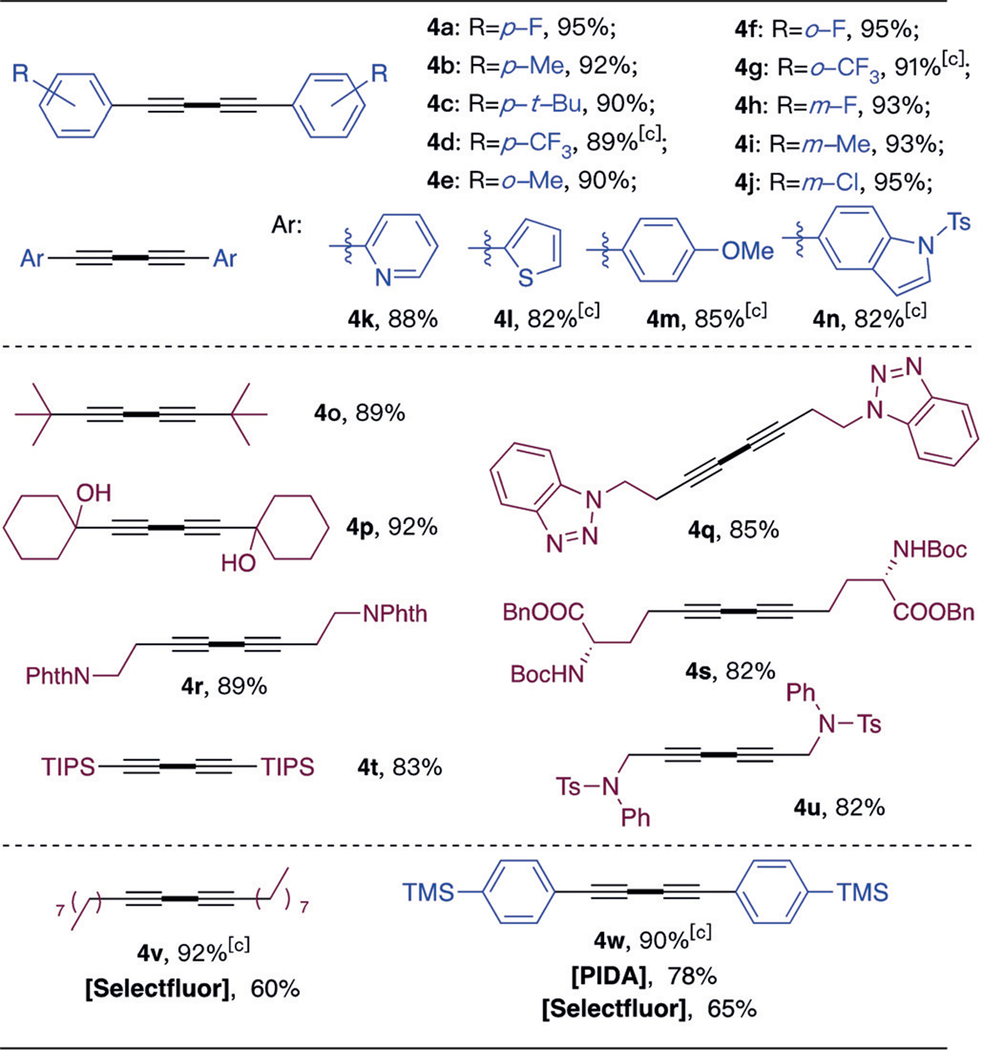

Using this electrochemical method, homo-coupling of aromatic alkynes was realized with excellent yields (> 90%) in almost all cases. Both electron-donating group (EDG)- and electron-withdrawing group (EWG)-modified phenylacetylenes worked well (4a-4j), including sterically hindered ortho substituted substrates (4e-4g). Notably, 2-pyridinyl 4k was also suitable, even with the potential for nitrogen coordination at the gold catalyst. In addition, highly electron-rich substrates 4l, 4m, and 4n were also compatible with these electrochemical condition. Aliphatic alkynes worked well, giving the desired diynes in good to excellent yields. It is important to note that this electrochemical anode oxidation could serve as an alternative method compared to traditional PIDA and Selectfluor oxidation. For example, an aliphatic alkyne with a long chain (4v), which is a challenging substrate under Cormąs conditions with Selecfluor as an oxidant, was achieved in excellent yield.[14] Also, substrates 4o and 4t could be easily prepared and separated from iodobenzene contamination, which is an inevitable byproduct under PIDA conditions. Sensitive functional groups, such as TMS, were also well tolerated.[15]

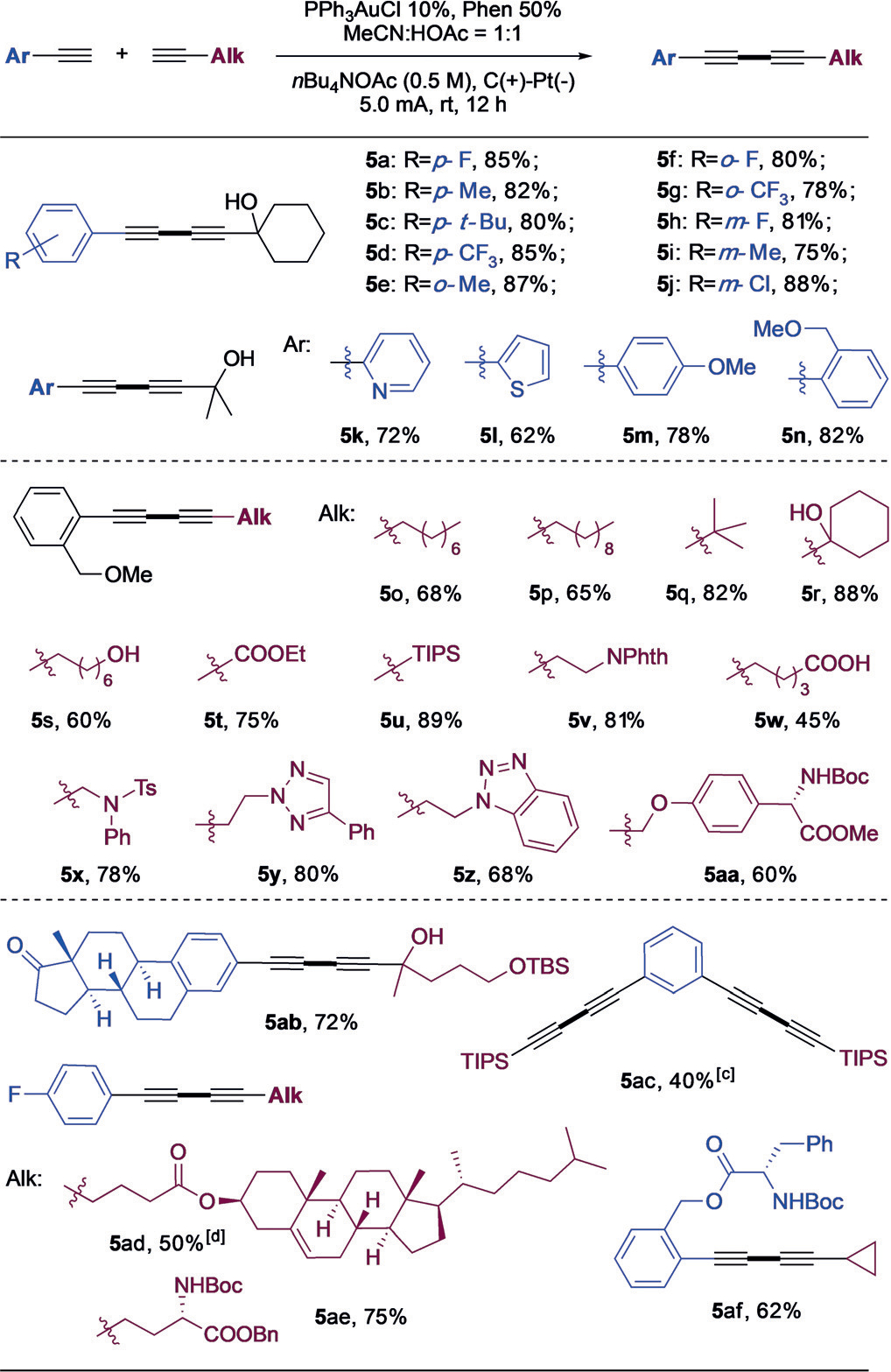

A powerful feature of the gold-catalyzed diyne oxidative coupling of alkynes is access to unsymmetrical 1,3-diynes.[16] To explore the possibility of achieving selective unsymmetrical cross-coupling under electrochemical conditions, we conducted reactions between aromatic alkyne 3a and propargyl alcohol (formation of product 5a). After a screening of conditions, PPh3AuCl (10%) and MeCN/HOAc (1:1) were revealed as the optimal conditions, providing 5a in 85% yield of isolated product with excellent selectivity (up to 8:1, 5a:4a). With the new optimal conditions in hand, various aromatic and aliphatic alkynes were tested.

As shown in Table 3, a wide variety of unsymmetrical diynes (5) were successfully prepared. In general, aryl alkynes provided good to excellent yields regardless of the substituents on the benzene rings (5a-5j). Heteroaryl alkynes, such as those with pyridine and thiophene rings (5k and 5l), were also suitable under electrochemical conditions, though with modest yields. Different aliphatic alkynes were then tested. Aliphatic chain containing various functional groups, such as alcohol (5r, 5s), ester (5t), acid (5w), phthalimide (5v), and amino acid (5aa) groups worked well. Both TBS (5ab) and TIPS (5u, 5ac) protecting groups were tolerated in this reaction. Some biologically relevant functional groups, including peptides (5ae, 5af), terpenes (5ab, 5ad), and triazoles (5y, 5z) proved successful for this transformation, which highlights the broad scope of this new strategy. Interestingly, no cyclopropane-ring-opening product was observed (5af), thus implying that a radical pathway is not likely involved.

Table 3:

|

General reaction conditions: aromatic alkyne (0.25 mmol), aliphatic alkyne (0.75 mmol), PPh 3AuCl (10 mol%), and Phen (50 mol%) was added into 0.5m nBu4NOAc in MeCN/HOAc = 1:1, 5 mL. The reaction was performed under constant current (5 mA) at r.t.

Yield of isolated product.

PPh3AuCl (20 mol%), and Phen (100 mol%). [d] DCM/HOAc=1:1.

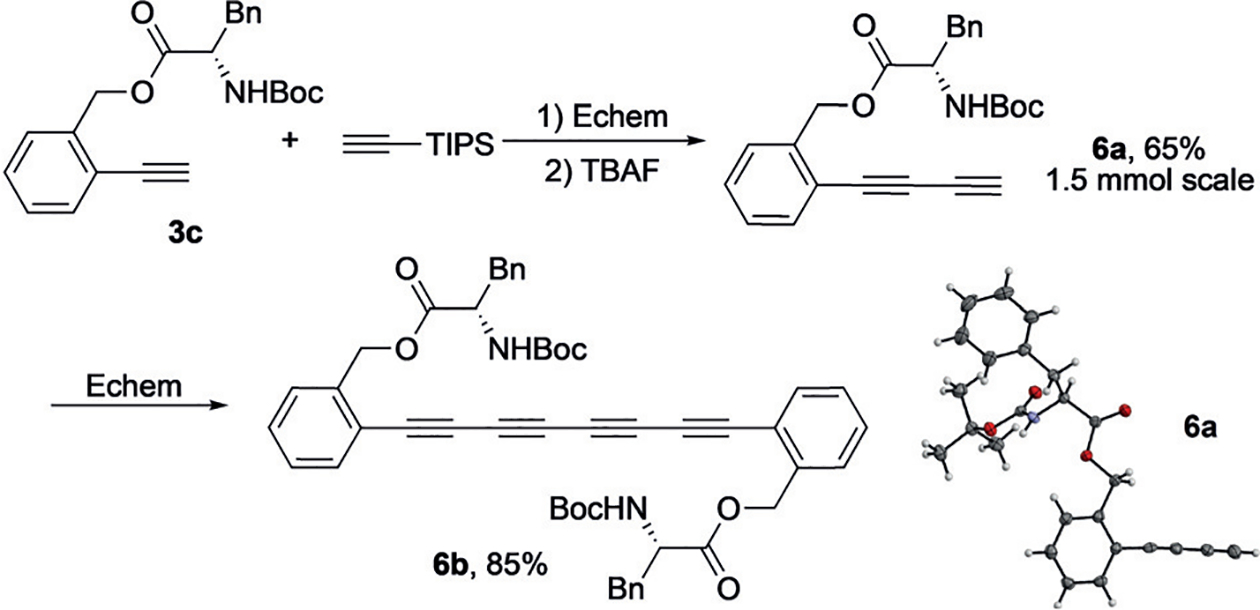

To further demonstrate the synthetic utility of this method, a 1.5 mmol scale reaction of 3c was carried out, providing cross-coupling product in 80% yield (Figure 2). The following one-pot deprotection offered 6a in 65% overall yield and the structure was confirmed unambiguously by X-ray crystallography. Moreover, homo-coupling of 6a was also successfully achieved, giving tetra-yne 6b in 85% yield with an amino acid moiety as a valuable synthetic handle.

Figure 2.

Challenging alkyne coupling.

In summary, we report the first example of electrochemical anodic oxidation of AuI to AuIII. As a result, the gold-catalyzed oxidative coupling of terminal alkynes was successfully achieved with a broad substrate scope and excellent functional-group tolerance under electrochemical conditions. This method represents a new atom-economic way to achieve gold redox chemistry. The mild nature and versatility of this reaction may offer new perspectives and insights into the synthetic utility and fundamental mechanistic understanding of AuI/AuIII redox catalysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the NSF (CHE-1665122 & CHE-1915878) and NIH (1R01GM120240-01) for financial support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information and the ORCID identification number(s) for the author(s) of this article can be found under: https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201909082.

Contributor Information

Xiaohan Ye, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620 (USA).

Pengyi Zhao, Department of Chemistry and Environmental Science, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, NJ 07102 (USA).

Shuyao Zhang, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida Tampa, FL 33620 (USA).

Yanbin Zhang, Department of Chemistry, Fudan University, Shanghai 200438 (China).

Hao Guo, Department of Chemistry, Fudan University, Shanghai 200438 (China).

Hao Chen, Department of Chemistry and Environmental Science, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, NJ 07102 (USA).

Xiaodong Shi, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida Tampa, FL 33620 (USA).

References

- [1].Hashmi ASK, Hutchings GJ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2006, 45, 7896–7936; Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 8064 – 8105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Gorin DJ, Toste FD, Nature 2007, 446, 395–403; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sengupta S, Shi XD, ChemCatChem 2010, 2, 609–619; [Google Scholar]; c) Dorel R, Echavarren AM, Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 9028–9072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Wegner HA, Auzias M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 8236–8247; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 8386 – 8397; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Garcia P, Malacria M, Aubert C, Gandon V, Fensterbank L, ChemCatChem 2010, 2, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bratsch SG, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1989, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Selected reviews of gold oxidation with external oxidant:Kar A, Mangu N, Kaiser HM, Tse MK, J. Organomet. Chem 2009, 694, 524–537;Zheng Z, Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhang L, Chem. Soc. Rev 2016, 45, 4448–4458;Miró J, del Pozo C, Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 11924–11966;Kramer S, Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22, 15584–15598; For selected examples, see:Zhang G,Peng Y, Cui L, Zhang L, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 3112–3115; Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 3158 – 3161;de Haro T, Nevado C, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 1512–1513;Ball LT,Lloyd-Jones GC, Russell CA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 254–264.

- [6]. Selected reviews of gold oxidation without external oxidant:Hopkinson MN, Tlahuext-Aca A, Glorius F, Acc. Chem. Res 2016, 49, 2261–2272;Akram MO, Banerjee S, Saswade SS, Bedi V, Patil NT, Chem. Commun 2018, 54, 11069–11083; For selected examples, see:Cai R, Lu M, Aguilera EY, Xi Y, Akhmedov NG, Petersen JL, Chen H, Shi X, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 8772–8776; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 8896 – 8900;Huang L, Rudolph M, Rominger F, Hashmi ASK, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 4808–4813; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 4888 – 4893;Wang J, Zhang S, Xu C, Wojtas L, Akhmedov NG, Chen H, Shi X, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 6915–6920; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 7031 – 7036;Levin MD, Toste FD, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 6211–6215; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 6325 – 6329.

- [7]. Selected reviews:Horn EJ, Rosen BR, Baran PS, ACS Cent. Sci 2016, 2, 302–308;Yan M, Kawamata Y, Baran PS, Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 13230–13319;Yan M, Kawamata Y, Baran PS, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 4149–4155; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 4219 – 4225;Mçhle S, Zirbes M, Rodrigo E, Gieshoff T, Wiebe A, Waldvogel SR, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 6018–6041; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 6124 – 6149.

- [8]. Review:Moeller KD, Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 9527–9554; For selected examples, see:Xiong P, Long H, Song J, Wang Y, Li JF, Xu H-C, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 16387–16391;Lennox AJJ, Goes SL, Webster MP, Koolman HF, Djuric SW, Stahl SS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 11227–11231;Liang Y, Lin F, Adeli Y, Jin R, Jiao N, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 4566–4570; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 4614 – 4618;Zhang L, Liardet L, Luo J, Ren D, Grätzel M, Hu X, Nat. Catal 2019, 2, 366–373.

- [9]. Reviews:Sauermann N, Meyer TH, Qiu Y, Ackermann L, ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 7086–7103;Meyer TH, Finger LH, Gandeepan P, Ackermann L, Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 63–76;Ma C, Fang P, Mei T-S, ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 7179–7189; For selected examples, see:Fu N, Sauer GS, Saha A, Loo A, Lin S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 575–579;28045542Qiu Y, Scheremetjew A, Ackermann L, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 2731–2738;Gao X, Wang P, Zeng L, Tang S, Lei A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 4195–4199;Shrestha A, Lee M, Dunn AL, Sanford MS, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 204–207.

- [10].a) Bunz UHF, Chem. Rev 2000, 100, 1605–1644; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shi W, Lei A, Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 2763–2772; [Google Scholar]; c) Asiri AM, Hashmi ASK, Chem. Soc. Rev 2016, 45, 4471–4503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tang S, Liu Y, Lei A, Chem 2018, 4, 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Ebule RE, Malhotra D, Hammond GB, Xu B, Adv. Synth. Catal 2016, 358, 1478–1481; [Google Scholar]; b) Goodwin JA, Aponick A, Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 8730–8741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Duan H, Sengupta S, Petersen JL, Akhmedov NG, Shi X,J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 12100–12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Leyva-Pérez A, Doménech A, Al-Resayes SI, Corma A, ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Brenzovich WE, Brazeau J-F, Toste FD, Org. Lett 2010, 12, 4728–4731; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ball LT, Lloyd-Jones GC, Russell CA, Science, 2012, 337, 1644–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Leyva-Pérez A, Doménech-Carbó A, Corma A, Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 6703; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li X, Xie X, Sun N, Liu Y, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 6994–6998; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 7098 – 7102; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhu M, Ning M, Fu W, Xu C, Zou G, Bull. Korean Chem. Soc 2012, 33, 1325–1328; [Google Scholar]; d) Peng H, Xi Y, Ronaghi N, Dong B, Akhmedov NG, Shi X, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 13174–13177; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Ye X, Peng H, Wei C, Yuan T, Wojtas L, Shi X, Chem 2018, 4, 1983–1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.