Introduction

70 years ago, Eleanor Roosevelt grounded human rights “in small places, close to home (…) the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice and dignity”.1

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted on Dec 10, 1948, established a modern human rights foundation that has become a cornerstone of global health, central to public health policies, programmes, and practices. To commemorate the 70th anniversary of this seminal declaration, we trace the evolution of human rights in global health, linking the past, present, and future of health as a human right (figure 1 ). This future remains uncertain. As contemporary challenges imperil continuing advancements, threatening both human rights protections and global health governance, the future will depend, as it has in the past, on sustained political engagement to realise human rights in global health.

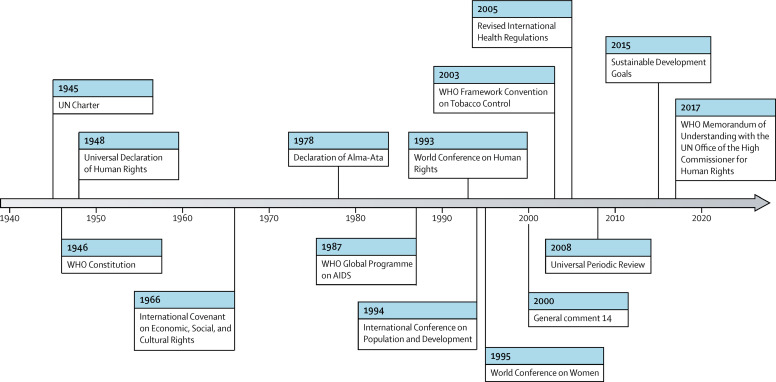

Figure 1.

The international development of human rights for health (1948–2018)

Post-war birth of human rights in global health governance

Human rights provide a universal framework for advancing global health with justice, transforming moral imperatives into legal entitlements.2 Created out of the atrocities of World War II, states in the newly formed UN established human rights under international law. The 1945 UN Charter became the first international treaty to recognise human rights, which form the principal foundation of this new world body. Operating through the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), the UN would “make recommendations for the purpose of promoting respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all”.3

With the UN Charter also calling for the establishment of an international health organisation, WHO had the responsibility to operationalise human rights for public health. The 1946 WHO Constitution declared, for the first time, that “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being”, thereby establishing government responsibilities to ensure “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.4 In creating a rights-based foundation for global health governance, the WHO Constitution represented the world's most expansive conceptualisation of international responsibility for health.5

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights sets a human rights standard for health

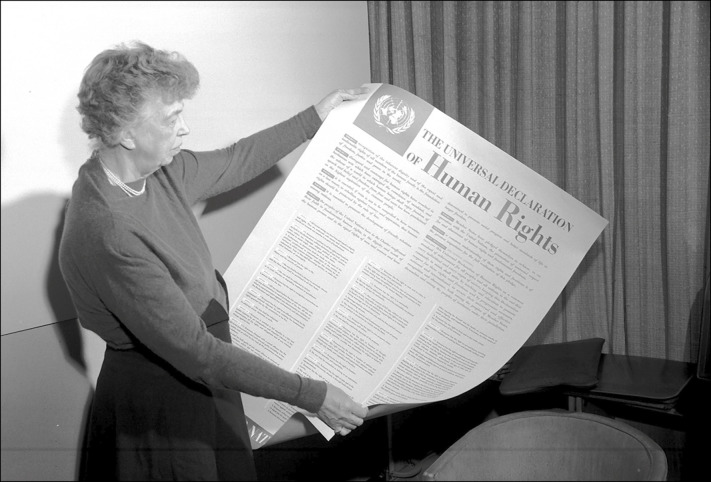

The UN General Assembly then adopted the 1948 UDHR (figure 2 ), enumerating a broad set of fundamental human rights and proclaiming “a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations”.6 Drawing from the WHO Constitution, public health became central to the UDHR agenda, with ECOSOC's Commission on Human Rights highlighting the importance of both medical care and underlying determinants of health.7 Reflecting rising national health systems and theories of social medicine,8 the right to health would encompass a holistic vision of patient and population-based health.

Figure 2.

Eleanor Roosevelt, UN commission on Human Rights chair from 1946–52, commemorating the 1948 adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Through this holistic vision, the UDHR situated health under the right to an adequate standard of living: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control”.6 The human right to health, thus, encompassed both individual health services and national health systems, with national health systems including social measures for public health.9

Cold War limits to the right to health

Despite the early promise of human rights in advancing health, the Cold War presented formidable political obstacles. The Cold War superpowers (USA and Soviet Union) held sharply divergent positions on human rights, with the Western states embracing civil and political rights and the Soviet Bloc favouring economic and social rights.10 The comprehensive vision of the UDHR unravelled along ideological lines, with the UN codifying two separate covenants: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

This opposition to socioeconomic rights resulted in a narrow definition of the right to health and health determinants under the 1966 ICESCR. States recognised “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”, but only a limited set of steps were described to progressively realise this right.11 Yet, even as Western states continued to resist the expansion of a rights-based approach to health, WHO observed that “people are beginning to ask for health, and to regard it as a right”.12

Right to health reborn in the Declaration of Alma-Ata

By the 1970s, WHO recognised the political influence of the right to health in building international support for primary health care.13 WHO's normative leadership was encapsulated in its Health For All campaign, pressing prosperous nations to assume international obligations for the health of the least powerful people.14 WHO engaged this rights-based strategy in economic development debates, joining low-income and middle-income countries in calling for a New International Economic Order.15 Exercising its constitutional authority to set international norms for public health, WHO structured global health policy through the 1978 Declaration of Alma-Ata.16

To memorialise the multisectoral policies needed to realise the right to health, WHO and UNICEF brought together governments and civil society at the International Conference on Primary Health Care in Alma-Ata in the Soviet Union. The resulting Declaration of Alma-Ata recognised the importance of participatory, broad-based socioeconomic development to build sustainable, comprehensive primary health-care systems. Viewing health inequalities as a common concern to all countries, the Declaration reaffirmed health as a fundamental human right and worldwide social goal,17 enumerating rights-based obligations for primary health care.18

Human rights in the AIDS pandemic

Although the Declaration of Alma-Ata faltered in the early 1980s,19 with governments unable to promote national health systems amid neoliberal economic policies, the unfolding AIDS pandemic would give rise to the modern health and human rights movement. Reacting to societal stigmatisation of marginalised communities, discriminatory criminalisation of key populations, and public health infringements on individual liberty, civil society rose up to demand rights. AIDS activists fiercely challenged policy makers. Rights-based campaigns resounded throughout the world: Silence is Death; Government has Blood on its Hands; Fight Back, Fight AIDS.2

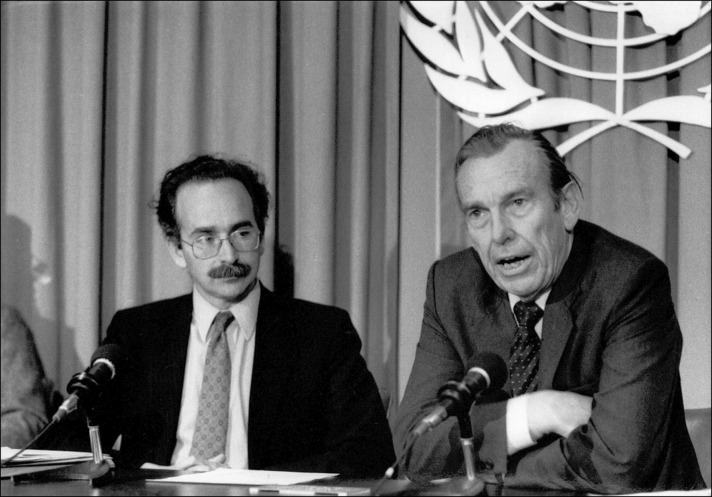

WHO came to embrace an inextricable link between public health and human rights in the AIDS response.20 WHO's Global Programme on AIDS, launched in 1987 (figure 3 ), shaped a rights-based framework for global health.21 International guidelines recommended risk reduction strategies, such as needle exchanges, transitioning the AIDS response from punitive measures to health promotion.22 As scientific breakthroughs ushered in the antiretroviral era, AIDS activists demanded universal access to treatment as a human rights imperative, giving rise to transformative institutions, from The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief to The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria.23

Figure 3.

Jonathan Mann, WHO Global Programme on AIDS Director from 1986–90, and Halfdan Mahler, WHO Director-General from 1973–88, on the first World AIDS Day, Dec 1, 1988

Human rights reinterpreted for a globalising world

With health inequalities rising in a globalising world, human rights advocacy extended beyond AIDS to a wide range of public health threats.24 As human rights flourished in the post-Cold War era, the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights formed a new global consensus that all human rights are universal, indivisible, interdependent, and inter-related.25 This consensus found voice in the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development and the 1995 World Conference on Women, joining civil and political rights with economic and social rights as a foundation for sexual and reproductive health.26 In 1997, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan called on all UN agencies to mainstream human rights in all their activities. WHO enlisted its first human rights advisor to operationalise a rights-based approach in its programmes and collaborate with the UN human rights system.27

At the turn of the millennium, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, charged with overseeing ICESCR implementation, adopted general comment 14, providing an authoritative interpretation of the right to health.28 The general comment went beyond preventive and curative health care to address underlying determinants of health beyond the health sector, including food, housing, work, education, non-discrimination, and equality.29 The UN Special Rapporteurs on the Right to Health and WHO's Commission on Social Determinants of Health thereafter elaborated the multisectoral obligations needed to implement health-related rights in areas such as mental health, health behaviour, maternal mortality, and access to treatment.

Operationalising health-related rights

As the UN shifted to a new era of implementation in human rights advancement, WHO responded through global health law.30 The 2003 Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) adopted robust demand and supply reduction strategies while banning tobacco industry participation in policy making.31 The FCTC gave rise to active civil society engagement, with the Framework Convention Alliance (a network of 500 non-governmental organisations from 100 countries) pushing governments to implement treaty obligations, promote gender rights, and set indicators for accountability.

With the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic exposing major gaps in the International Health Regulations (IHR), the principal treaty governing global health security, WHO member states saw human rights as vital for controlling infectious diseases. WHO fundamentally revised the IHR in 2005, with human rights forming one of three major pillars of IHR implementation. The IHR now requires “full respect for the dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms of persons,”32 minimising restrictions on individual freedoms and prohibiting discrimination in health measures.

Responding to government and civil society criticism that the UN had ignored human rights violations, the UN replaced the Human Rights Commission with the Human Rights Council, providing new human rights mechanisms for public health accountability. In 2008, the UN Human Rights Council launched the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) to monitor national human rights obligations.33 Civil society has had a prominent role in reporting to the UPR, holding governments accountable for implementing health-related human rights. Health featured in nearly a quarter of all recommendations made under the first cycle of the UPR, with particular attention to gender-based violence.34

Universal health coverage as a foundation for the health agenda in the Sustainable Development Goals era

Universal health coverage (UHC) has come to the forefront of WHO's efforts to strengthen health systems, serving as an economic framework for health systems financing35 and a political platform for health advocacy under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).36 UHC is founded upon the notion that health is a human right—an entitlement, not a commodity—and that the progressive realisation of the right to health can be assessed by the expansion of priority services, the inclusion of more people, and the reduction of out-of-pocket payments.37

To reach marginalised people, this equity-oriented, people-centred approach to expanding access to health seeks to protect disadvantaged populations from financial impoverishment, ensuring good quality services for all.38 Understanding who is being missed, and why, requires disaggregated data, focusing attention on the root causes of exclusion, the social construction of gender, and the development of interventions that benefit impoverished populations.39 The 2018 Astana Declaration, renewing human rights pledges from the Declaration of Alma-Ata, has recommitted governments to primary health care as an essential step towards UHC.40 “Finding that all roads lead to UHC”,41 WHO views UHC as the “best path to live up to WHO's constitutional commitment to the right to health”.42

Contemporary threats to human rights in global health

As the world celebrates the 70th anniversary of the UDHR, rising challenges are placing at risk hard-won gains for human rights in global health. Financial constraints are undermining advances in public health, including in HIV/AIDS, since HIV prevention efforts have stalled, incidence is rising among marginalised populations, and investments in high-impact interventions focused on those populations most at risk are restricted. Racial and ethnic minorities continue to experience stigma, discrimination, and exclusion, while pervasive gender norms and stereotypes endure, with harmful repercussions on health and wellbeing as well as access to health services. Shrinking civil society space restricts dialogue with those whose experience and voice are vital to reduce health inequities. Attacks on health and human rights stand in direct contradiction to international human rights and humanitarian law.43 Global threats, such as climate change, armed conflict, and mass migration, are exacerbating divisions within and across nations, in stark contrast to the UDHR's proclamation of common humanity.44

In 2018, in response to these challenges, WHO revitalised its commitment to a rights-based approach to health. The 13th General Programme of Work, WHO's 5-year strategy, calls for leadership on equity, gender, and human rights to achieve its 3 billion objective: 1 billion more people accessing UHC, 1 billion more people protected from health emergencies, and 1 billion more people enjoying better health and wellbeing.45 WHO is expanding partnerships with civil society, convening a civil society task team to promote inclusive participation to achieve its goals. WHO has also signed a 5-year Memorandum of Understanding with the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to bolster technical and political cooperation.

Towards a hopeful future

Human rights have brought the world together in unprecedented solidarity over the past 70 years, recognising the inherent dignity of every person as an imperative for global health. Dec 10 is Human Rights Day, in commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the UDHR. While we celebrate the enduring legacies of human rights, we must also strive to identify and rectify the constraints on rights-based governance for public health in a globalising world. It is more important than ever for the health and human rights communities to stand together as partners to uphold the values of the UDHR and resist contemporary threats to human rights. The human rights progress of the past, bringing together top-down leadership in global health governance with bottom-up civil society advocacy, highlights the importance of sustained political engagement to realise the right to health. Health practitioners have a crucial role in this political engagement, advancing rights-based public health policies, programmes, and practices that are essential to secure the future of human rights in global health.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Princess Nothemba Simelela for thoughtful comments.

Contributors

All authors contributed equally to this Viewpoint.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Roosevelt E. United Nations; New York, NY: 1958. In your hands: a guide for community action for the tenth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gostin LO. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2014. Global health law. [Google Scholar]

- 3.UN . United Nations; New York, NY: 1945. Charter of the United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 1946. Constitution of the World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen CE. World health and world politics. Int Organ. 1950;4:27–43. [Google Scholar]

- 6.UN General Assembly . United Nations; New York, NY: 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. [Google Scholar]

- 7.UN Commission on Human Rights . United Nations; New York, NY: 1947. Secretariat draft outline to Economic and Social Council. Commission on human rights drafting committee. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenks CW. The five economic and social rights. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 1946;243:40–46. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morsink J. University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia, PA: 1999. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: origins, drafting, and intent. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cranston MW. Taplinger; New York, NY: 1973. What are human rights. [Google Scholar]

- 11.UN General Assembly . United Nations; New York, NY: 1966. International covenant on economic, social and cultural rights. [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 1968. The second ten years of the World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meier BM. Global health governance and the contentious politics of human rights: mainstreaming the right to health for public health advancement. Stanford J Int Law. 2010;46:1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunn S, William A. The right to health through international cooperation. International Colloquium on the Right to Health Protection. Torino, Italy, 1983.

- 15.Pannenborg CO. Sijthoff & Noordhoff; Alphen aan den Rijn: 1979. A new international health order. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sijthoff and Noordhoff; Alphen aan den Rijn: 1979. The right to health as a human right: workshop, The Hague: July 27–29, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 1978. Declaration of Alma-Ata. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roscam Abbing HDC. Kluwer-Deventer; Boston, MA: 1979. International organizations in Europe and the right to health care. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakajima H. Priorities and opportunities for international cooperation: experiences in the WHO Western Pacific region. In: Reich MR, Marui E, editors. International cooperation for health: problems, prospects, and priorities. Auburn House Publishing Co; Dover, MA: 1989. pp. 317–331. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann J, Gostin LO, Gruskin S, Brennan T, Lazzarini Z, Fineberg HV. Health and human rights. Health Hum Rights. 1994;1:6–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gruskin S, Mills EJ, Tarantola D. History, principles, and practice of health and human rights. Lancet. 2007;370:449–455. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gostin LO, Lazzarini Z. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1997. Human rights and public health in the AIDS pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Government of South Africa. Minister of Health versus Treatment Action Campaign, 2002.

- 24.Meier BM, Gostin LO. Responding to the public health harms of a globalizing world through human rights in global governance. In: Meier BM, Gostin LO, editors. Human rights in global health: rights-based governance for a globalizing world. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2018. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner . United Nations; New York, NY: 1993. Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freedman LP. Human rights and the politics of risk and blame: lessons from the reproductive rights movement. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1997;52:165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meier BM, Onzivu W. The evolution of human rights in World Health Organization policy and the future of human rights through global health governance. Public Health. 2014;128:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.UN Committee on Economic. Social and Cultural Rights . United Nations; New York, NY: 2000. General comment 14: the right to the highest attainable standard of health. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meier BM, Mori LM. The highest attainable standard: advancing a collective human right to public health. Columbia Hum Rights Law Review. 2005;37:101–147. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunt P. Configuring the UN human rights system in the “era of implementation”: mainland and archipelago. Hum Rights Quart. 2017;39:489–538. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hammond R, Assunta M. The framework convention on tobacco control: promising start, uncertain future. Tob Control. 2003;12:241–242. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.3.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. International health regulations. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bueno de Mesquita JR, Fuchs C, Evans DP. The future of human rights accountability for global health through the universal periodic review. In: Meier BM, Gostin LO, editors. Human rights in global health: rights-based governance for a globalizing world. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2018. pp. 537–556. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bueno de Mesquita J, Thomas R, Gauter C. Monitoring the sustainable development goals through human rights accountability reviews. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:627–633. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.204412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage: final report of the WHO consultative group on equity and Universal Health Coverage. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan M. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage. Health Syst Reform. 2016;2:5–7. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2015.1111288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bustreo F, Magar V, Khosla R, Stahlhofer M, Thomas R. The future of human rights in WHO. In: Meier BM, Gostin LO, editors. Human rights in global health: rights-based governance for a globalizing world. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2018. pp. 155–176. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watkins DA, Yamey G, Schäferhoff M. Alma-Ata at 40 years: reflections from the Lancet Commission on Investing in Health. Lancet. 2018;392:1434–1460. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32389-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2018. Global Conference on Primary Health Care: Declaration of Astana. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghebreyesus TA. All roads lead to universal health coverage. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e839–e840. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meier BM. Human rights in the World Health Organization: views of the Director-General candidates. Health Hum Rights. 2017;19:293–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alston P. The populist challenge to human rights. J Hum Rights Pract. 2017;9:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gostin LO, Friedman E. Global health: a pivotal moment of opportunity and peril. Health Affair. 2017;36:159–165. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2018. Thirteenth general programme of work 2019–2023. [Google Scholar]