Abstract

Background: Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by amyloid-beta plaques, neuronal loss, and cognitive dysfunction. Oxidative stress plays a key role in the pathophysiology of AD, and it has been suggested that antioxidants may slow the progress of the disease. In this study, the possible protective effects of pelargonidin (a natural flavonoid) against amyloid β (Aβ)-induced behavioral deficits was investigated in rats.

Methods: Adult Wistar male rats were treated with intrahippocampal injections of the Aβ (aa 25-35) and intraperitoneal injection of pelargonidin. Learning and spatial memory were tested using the Morris water maze (MWM) task. The antioxidant activity was evaluated using the ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay (FRAP assay). Data were analyzed using SPSS 20, and value of p≤0.05 was considered significant.

Results: The results of this study showed that Aβ significantly increased escape latency and the distance traveled in the MWM, and pelargonidin attenuated these behavioral changes. Aβ induced a significant decrease in the total thiol content of hippocampus, and pelargonidin restored the hippocampal antioxidant capacity.

Conclusion: The results of this study suggest that pelargonidin can improve Aβ-induced behavioral changes in rats.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Amyloid β-peptide, Pelargonidin, Memory impairment, Hippocampus, Oxidative stress

↑ What is “already known” in this topic:

Alzheimer's disease (AD), as a major neurodegenerative disorder, is associated with oxidative stress and memory impairment and pelargonidin has antioxidant properties.

→ What this article adds:

Pelargonidin represents free radical scavenging properties and is able to improve amyloid beta-induced neurotoxicity in rats.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as a neurodegenerative disorder, is the most common cause of dementia. Astrogliosis, neurofibrillary tangles, senile plaques, and neuronal and synaptic loss in several parts of the brain have become universally accepted as the neuropathological hallmarks of the disease (1, 2). Astrogliosis is an abnormal increase in the number of reactive astrocytes and can cause scar formation and inhibition of axonal regeneration (3). Neurofibrillary tangles are the neuropathological characteristic of AD lesion which is composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (4). The core of the plaque consists of β-amyloid and other proteins (4). Aβ causes peroxidation of lipid, oxidation of protein, the formation of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and acrolein that change the conformation of membrane proteins and consequently results in neuronal death in the hippocampus (5). Furthermore, Aβ-induced damage to the mitochondrial membrane increases intracellular H2O2, damages hippocampal neurons, and results in memory impairment (6-8). Epidemiological and experimental data revealed a negative correlation between the intake of a diet enriched in fruit and vegetables and the risk of neurodegenerative disease (9-12). There is considerable evidence that plant flavonoids with strong antioxidant activity exhibit therapeutic activity involving cardioprotection and neuroprotection (13, 14). Anthocyanins and their aglycone derivative anthocyanins, as a member of flavonoids, have been reported to provide neuro and hepatoprotective effects and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease (15-17). Some of the current treatments for AD are designed to increase the ability of biological systems to detoxify the reactive intermediates and repair the damage caused by them (18, 19). Antioxidants offer a promising approach toward neuroprotection by Aβ-exposure (20, 21). Of these groups, pelargonidin-3-o-galactoside (pg3g) shows protective activities in diabetic neuropathic hyperalgesia and Hemi-parkinsonism (22, 23). Roy et al found that IP injection of pelargonidin initiated a significant increase in the amount of free radical scavenging enzymes such as catalase and serum superoxide dismutase (SOD) in diabetic rats. Following 2 weeks of treatment with pelargonidin, serum malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, an indicator of production of free radicals, has decreased (23). The present study was designed to determine whether the Aβ-induced memory impairment could be attenuated by pelargonidin administration and whether any changes produced by pelargonidin could relate to its antioxidant capacity.

Methods

Chemicals

Aβ (25-35) and pelargonidin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Aβ 25-35 was aggregated by incubation in 37°C for 4 days and solubilized in sterile water at 1 µg/µL concentration and stored at –20°C.

Experimental design and animals' classification

All animal experiments in this study have been approved by the Veterinary Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (No: 93/105/610) and have been performed according to the National Institute of Health Guide for care and use of laboratory animals. In this study, 28 male Wistar rats (250 - 300 g, 12 weeks) were obtained from the animal center of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (Hamadan, Iran). Animals were randomly divided into 4 groups (7 rats in each group): (1) control (intact) group, (2) sham-operated group, (3) Aβ (25-35) lesioned animals (5µg), and (4) pelargonidin-treated Aβ groups.

Intrahippocampal injection of Aβ 25- 35

Under ketamine (100mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) anesthesia and using a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA), Aβ solution (5µL) was injected bilaterally into the hippocampi over 1 µL/2 min. The cannula was left in place for 2 minutes after each injection to allow for diffusion. Relative to the bregma and with the stereotaxic arm at °0, the coordinates for the dentate gyrus were posterior -3.6, lateral ± 2.3, and dorsal 3mm. Sham-operated rats received vehicle solution (24). Two weeks after Aβ injection, pelargonidin-treated Aβ-injected group received a single intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 3 mg/kg pelargonidin (23).

Assessment of spatial memory

The Morris water maze task was used to assess the spatial learning and memory. It has been reported that the striatum, the frontal cortex, and especially the hippocampus were involved in navigation in the Morris water maze task (25).

The animals were tested for spatial memory using a Morris Water Maze (MWM) apparatus (26). In brief, water-filled circular pool (60 cm in depth, 180 cm in diameter), with 4 quadrants and starting locations (North, East, South, and West) were used. There was a plate positioned 1 cm below the water in the northern quadrant. The animals were trained for 4 days, which consisted of 2 blocks with 4 trials; each trail lasted for 90 seconds and there was a 30-second rest between the 2 trials. There was a 5-minute rest between the 2 consecutive blocks. The escape latency and traveled distance were recorded (acquisition stage) by a video camera (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA). On day 5, the platform was removed, a probe trial was performed for 60 seconds, and the percentage of the time spent in the target quadrant was recorded (retention stage). During the acquisition stage, the event is perceived and the related information is initially stored in the memory; and in the retention stage, information resides in the memory.

Ferric reducing/antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

At the end of the experiment, the hippocampus was dissected and gently homogenized in ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (0.1 M, pH 7.4) to give a 10% homogenous suspension and used for FRAP assay. According to Najafi et al (27), the homogenate was added to FRAP reagent and incubated at 37ºC for 10 minutes. The absorbance of the complex was read at 593 nm. FRAP values were expressed as nmol ferric ions reduced to ferrous form/mg tissue.

Data analysis

Data were expressed as mean± SEM. Statistical analysis of the escape latency and traveled distance during the training days in the MWM were performed using one-way and two-way ANOVA with repeated measures (GraphPad Prism 6 software). The data of the percent of the time spent in target quadrant of the probe and the FRAP value were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Tukey's post hoc test was used to determine the intergroup differences. Value of p≤0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Pelargonidin improved Aβ-induced memory and learning impairment in MWM

The effect of pelargonidin on acquisition memory deficit following Aβ administration

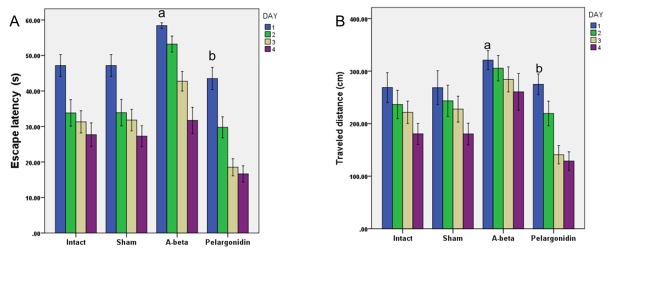

The data of the escape latency (the time spent to find the hidden platform) and traveled distance (the distance to find the hidden platform) during the training days were analyzed using two-way ANOVA; treatment was used as one factor, training days as the second factor, and interaction between training days and treatment as the third factor. The results of the two-way ANOVA showed substantial effects of treatment (p<0.001) and training days (p<0.001) in escape latency. However, no significant interaction was detected between training days and treatment. Escape latency was significantly lower in the intact and sham-operated groups compared to the Aβ-treated and pelargonidin groups (p<0.001) (Fig. 1A). Longer escape latency is an indicator of the more severe deficits in spatial memory. Furthermore, the results of this study showed that pelargonidin treatment causes a significant decrease in escape latency in comparison to the Aβ-treated group (p<0.001).

Fig. 1.

The protective effects of pelargonidin in Aβ (25-35)- triggered Alzheimer’s model, as illustrated by escape latency in water-maze tests. (A) The mean of escape latency in 4 consecutive trial days of the MWM. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (a: p < 0.001 vs intact and sham groups; b: p < 0.001 vs A- beta group). (B) The mean of traveled distance in 4 consecutive trial days of the MWM. Data present as mean ± S.E.M. (a: p<0.001 vs intact and sham groups; b: p<0.001 vs Aβ-group).

Consistent with the latency data, a significant effect of treatment (p<0.001) and training days (p<0.001) in the traveled distance was revealed. However, no major synergy between training days and treatment was observed. Also, the results revealed that over the course of 4 training days intact and sham-operated groups moved a shorter distance to find the hidden platform (traveled distance) than the Aβ-treated and pelargonidin groups (Fig. 1B). The results of post hoc Tukey's analysis demonstrated a significant difference between the intact and sham-operated groups and the rats, which received Aβ treatment (p<0.001). Aβ-treated rats that received pelargonidin showed less traveled distance in comparison to Aβ-treated group (p<0.001).

The effect ofpelargonidin on retentionmemorydeficitfollowingAβadministration

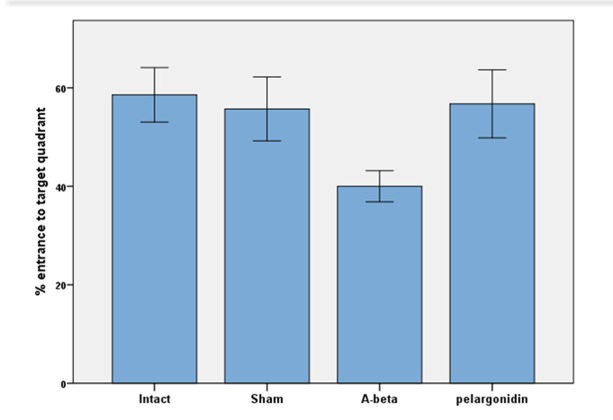

During the probe trial session, the percentage of the entrance to target quadrant was examined. Findings revealed that the time spent in the target quadrat was more in the intact group (58.57±5.53) than other groups (sham: 55.71±17.18; Aβ: 40.0±7.74; pelargonidin: 56.75±15.46, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The average percentage of entrance to target quarter in the probe trial in the MWM. The animals were trained prior to the test as described in the text. The travelled distance was measured upon recording their paths by a camera placed above the experimental tank. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M.

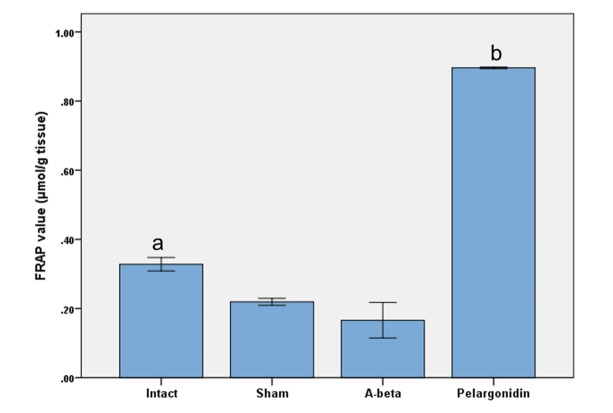

The effect of pelargonidin on FRAP in the hippocampusfollowingAβadministration

The results of the one-way analysis of variance of FRAP assay showed a significant decrease in antioxidant power of hippocampus homogenate samples in Aβ-treated rats compared to intact group (p=0.010) (Fig. 3). Also, pelargonidin treatment increased the antioxidant power of hippocampus homogenate when compared to other groups (p<0.001).

Fig. 3.

The effects of Aβ and pelargonidin treatment on the total thiol concentration of hippocampus homogenate samples. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (a: p=0.010 vs intact group; b: p < 0.001 vs other groups).

Discussion

In this study, it was found that pelargonidin, a natural flavonoid, attenuated Aβ-induced deficits in memory and antioxidant capacity. Also, Aβ injections (25-35) were used as an Alzheimer’s model in the rats. Consistent with previous studies, this study found that Aβ-induced changes in LTP in the granule cells of DG, which was associated with learning and memory impairment in the MWM (18, 28, 29). Evidence indicates that deposition of Aβ in the hippocampus can be one of the major pathological characteristics of AD that destroys neurons and results in cognitive deficits (30). It has been reported that application of Aβ into the neural membrane bilayer leads to free radical overproduction and causes the lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and consequently damages synapse function (31). Furthermore, it has been shown that injection of Aβ inhibits NMDA receptor-associated synaptic transmission, resulting in the decreased Ca2+influx and reducing the phosphorylation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II as well as Glu R1 subunits of AMPA receptors (32). Park et al have reported that Aβ deposition modulates NMDA receptors and nitric oxide synthase, induces oxidative stress in vivo, and may precipitate mitochondrial permeability transition opening (33).

In the present study, the FRAP assay results (a marker of antioxidant power) revealed that Aβ-injections reduced the antioxidant capacity of the hippocampus. In this context, it has been suggested that Aβ can induce massive oxidative challenge in neurons, including lipid peroxidation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation (5). Also, Aβ can decrease endogenous antioxidant enzymes, which protect cells against several endogenous and exogenous toxic compounds such as ROS that can lead to cognitive deficits (34). There is a direct correlation between the overproduction of free radicals and reduced antioxidant defense response in AD (35). The use of external antioxidant is one of the most common therapeutic approaches for the treatment of memory impairment and cognition function (18, 36). Among other experimental therapeutic approaches, several efforts are focused on the development of ways/chemicals (anthocynidin) that would reduce or eliminate Aβ-aggregation (37). Pelargonidin is an anthocyanidin that produces a characteristic orange color and can be found in berries, plums, pomegranates, and in large amounts in kidney beans. It can cross the brain blood barrier (38).

The results of the present study demonstrate that administration of pelargonidin exerts protective effects against Aβ-induced memory impairment in rats. Similarly, Roghani et al reported that pelargonidin can mitigate the Parkinson’s-like behaviors in animals (22). In addition, Skemiene et al showed the protective properties of pelargonidin on ischemia-induced apoptosis (39). In another study, administration of pelargonidin effectively restored the activity of some antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase in diabetic rats, indicating the antioxidant effects of pelargonidin (23). Several lines of evidence reported that anthocyanin, as a group of flavonoids, can provide strong neuroprotective effects and reduce cognitive deficits (40, 41). Neuroprotective effects of pelargonidin as an anthocyanin glycoside has been demonstrated in brain ischemia induced by permanent cerebral artery occlusion (42).

Flavonoids such as pelargonidin could decrease neuronal damage and loss (13) through mitigation of oxidative stress and the enhancement of an antioxidant defense system. As expected, Aβ-injection caused a reduction in antioxidant capacity as corroborated by a decrease in FRAP level. In agreement with previous investigations, administration of pelargonidin increased the antioxidant pool of hippocampi (22, 23). Overexpression of inflammatory mediators following microglia activation is a key agent in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity (43). Due to anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoid such as pelargonidin (44), it is possible that the protective effects of pelargonidin may also be due to anti-inflammatory actions; however, this needs to be further investigated.

These protective effects may be related to the ability of pelargonidin to control essential intracellular signaling cascades. Indeed, flavonoids are able to cross the blood-brain barrier, accumulate in the brain at nanomolar concentrations, and induce neuromodulatory effects through selective action on a number of protein kinases and lipid kinases signaling cascades (45).

Conclusion

Taken together, administration of pelargonidin inhibited oxidative stress, improved LTP, and attenuated the behavioral abnormalities induced by Aβ.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Iran National Science Foundation under the global grant measure (project No: 92004882). The authors express their appreciation to Adel Rezaei Moghadam, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada.

Conflict of Interests

None of the authors of this paper have a financial interest to be reported.

Cite this article as: Soleimani Asl S, Bergen H, Ashtari N, Amiri Sh, Łos MJ, Mehdizadeh M. Pelargonidin exhibits restoring effects against amyloid β-induced deficits in the hippocampus of male rats. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2019 (12 Dec);33:135. https://doi.org/10.34171/mjiri.33.135

References

- 1.Cvetkovi-DOÆI D, Skender-Gazibara M, Slobodan D. Neuropathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Oncol. 2001;9(3):195–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghavami S, Shojaei S, Yeganeh B, Ande SR, Jangamreddy JR, Mehrpour M. et al. Autophagy and apoptosis dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;112:24–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.10.004. Epub 2013/11/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verkhratsky A, Zorec R, Rodríguez JJ, Parpura V. Astroglia dynamics in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2016;26:74–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cork LC, Powers RE, Selkoe DJ, Davies P, Geyer JJ, Price DL. Neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in aged bears. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1988;47(6):629–41. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198811000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mark RJ, Lovell MA, Markesbery WR, Uchida K, Mattson MP. A role for 4‐hydroxynonenal, an aldehydic product of lipid peroxidation, in disruption of ion homeostasis and neuronal death induced by amyloid β‐peptide. J Neurochem. 1997;68(1):255–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68010255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keil U, Bonert A, Marques CA, Scherping I, Weyermann J, Strosznajder JB. et al. Amyloid β-induced changes in nitric oxide production and mitochondrial activity lead to apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(48):50310–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ha JS, Sung HY, Lim HM, Kwon KS, Park SS. PI3K–ERK1/2 activation contributes to extracellular H 2 O 2 generation in amyloid β toxicity. Neurosci Lett. 2012;526(2):112–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith EE, Muzikansky A, McCreary CR, Batool S, Viswanathan A, Dickerson BC. et al. Impaired memory is more closely associated with brain beta-amyloid than leukoaraiosis in hypertensive patients with cognitive symptoms. PloS One. 2018;13(1):e0191345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zielińska MA, Białecka A, Pietruszka B, Hamułka J. Vegetables and fruit, as a source of bioactive substances, and impact on memory and cognitive function of elderly. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2017;12 71(0):267–280. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.3812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pistollato F, Sumalla Cano S, Elio I, Masias Vergara M, Giampieri F, Battino M. Associations between Sleep, Cortisol Regulation, and Diet: Possible Implications for the Risk of Alzheimer Disease. Adv Nutr. 2016;15 7(4):679–89. doi: 10.3945/an.115.011775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight A, Bryan J, Murphy K. Is the Mediterranean diet a feasible approach to preserving cognitive function and reducing risk of dementia for older adults in Western countries? New insights and future directions. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;25:85–101. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luke AK, Evans EW, Bond DS, Thomas JG. Associations between omega fatty acid consumption and depressive symptoms among individuals seeking behavioural weight loss treatment. Obes Sci Pract. 2016;2(1):75–82. doi: 10.1002/osp4.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grassi D, Ferri C, Desideri G. Brain protection and cognitive function: cocoa flavonoids as nutraceuticals. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(2):145–51. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666151112145730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiserová H, Šimůnek T, Van Der Vijgh WJ, Bast A, Kvasničková E. Flavonoids as protectors against doxorubicin cardiotoxicity: role of iron chelation, antioxidant activity and inhibition of carbonyl reductase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772(9):1065–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Pascual-Teresa S, Moreno DA, García-Viguera C. Flavanols and anthocyanins in cardiovascular health: a review of current evidence. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11(4):1679–703. doi: 10.3390/ijms11041679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fontaine C, Cousin W, Plaisant M, Dani C, Peraldi P. Hedgehog signaling alters adipocyte maturation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell. 2008;26(4):1037–46. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin WH, Park SJ, Kim EJ. Protective effect of anthocyanins in middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion model of cerebral ischemia in rats. Life Sci. 2006;79(2):130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang T, Sun Q, Chen S. Oxidative stress: A major pathogenesis and potential therapeutic target of antioxidative agents in Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2016;147:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan S, Kantham S, Rao VM, Palanivelu MK, Pham HL, Shaw PN. et al. Metal chelation, radical scavenging and inhibition of Aβ 42 fibrillation by food constituents in relation to Alzheimer’s disease. Food Chem. 2016;199:185–94. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.11.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pachón-Angona I, Refouvelet B, Andrýs R, Martin H, Luzet V, Iriepa I, Moraleda I, Diez-Iriepa D, Oset-Gasque MJ, Marco-Contelles J, Musilek K, Ismaili L. Donepezil + chromone + melatonin hybrids as promising agents for Alzheimer's disease therapy. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2019;34(1):479–489. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1545766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young ML, Franklin JL. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ inhibits memory loss, neuropathology, and extends lifespan in aged 3xTg-AD mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2019;101:103409. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2019.103409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roghani M, Niknam A, Jalali-Nadoushan M-R, Kiasalari Z, Khalili M, Baluchnejadmojarad T. Oral pelargonidin exerts dose-dependent neuroprotection in 6-hydroxydopamine rat model of hemi-parkinsonism. Brain Res Bull. 2010;82(5):279–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy M, Sen S, Chakraborti AS. Action of pelargonidin on hyperglycemia and oxidative damage in diabetic rats: implication for glycation-induced hemoglobin modification. Life Sci. 2008;82(21):1102–10. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paxinos G, Watson C, Pennisi M, Topple A. Bregma, lambda and teh interaural midpoint in stereotaxic surgery with rats of different sex, strain and weight. J Neurosci Methods. 1985;13(2):139–43. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(85)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris R, Garrud P, Rawlins J, O'Keefe J. Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature. 1982;297(5868):681–3. doi: 10.1038/297681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Omidi G, Karimi SA, Rezvani-Kamran A, Monsef A, Shahidi S, Komaki A. The effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on diabetes induced memory deficits in rats. Metab Brain Dis. 2019;34(3):833–840. doi: 10.1007/s11011-019-00402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Najafi R, Sharifi AM, Hosseini A. Protective effects of alpha lipoic acid on high glucose-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. Metab Brain Dis. 2015;30(3):731–8. doi: 10.1007/s11011-014-9625-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei M, Xu H, Li Z, Wang Z, O'Malley TT, Zhang D. et al. Soluble Aβ oligomers impair hippocampal LTP by disrupting glutamatergic/GABAergic balance. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;85:111–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ford L, Crossley M, Williams T, Thorpe JR, Serpell LC, Kemenes G. Effects of Aβ exposure on long-term associative memory and its neuronal mechanisms in a defined neuronal network. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10614. doi: 10.1038/srep10614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I. et al. Amyloid-β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14(8):837–42. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butterfield DA, Lauderback CM. Lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation in Alzheimer’s disease brain: potential causes and consequences involving amyloid β-peptide-associated free radical oxidative stress 1, 2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32(11):1050–60. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00794-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao D, Watson JB, Xie CW. Amyloid β prevents activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and AMPA receptor phosphorylation during hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92(5):2853–8. doi: 10.1152/jn.00485.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parks JK, Smith TS, Trimmer PA, Bennett JP, Parker WD. Neurotoxic Aβ peptides increase oxidative stress in vivo through NMDA‐receptor and nitric‐oxide‐synthase mechanisms, and inhibit complex IV activity and induce a mitochondrial permeability transition in vitro. J Neurochem. 2001;76(4):1050–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lovell MA, Markesbery WR. Oxidative DNA damage in mild cognitive impairment and late-stage Alzheimer's disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(22):7497–504. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mancuso C, Scapagini G, Curro D, Giuffrida Stella AM, De Marco C, Butterfield DA. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction, free radical generation and cellular stress response in neurodegenerative disorders. Front Biosci. 2007;12(1):1107–23. doi: 10.2741/2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rezvani-Kamran A, Salehi I, Shahidi S, Zarei M, Moradkhani S, Komaki A. The effects of the hydroalcoholic extract of Rosa damascena on learning and memory in male rats consuming a high-fat diet. Pharm Biol. 2017;55(1):2065–2073. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2017.1362010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hauff K, Zamzow C, Law WJ, De Melo J, Kennedy K, Los M. Peptide-based approaches to treat asthma, arthritis, other autoimmune diseases and pathologies of the central nervous system. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2005;53(4):308–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Youdim KA, Shukitt-Hale B, Joseph JA. Flavonoids and the brain: interactions at the blood–brain barrier and their physiological effects on the central nervous system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37(11):1683–93. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skemiene K, Rakauskaite G, Trumbeckaite S, Liobikas J, Brown GC, Borutaite V. Anthocyanins block ischemia-induced apoptosis in the perfused heart and support mitochondrial respiration potentially by reducing cytosolic cytochrome c. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(1):23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rehman SU, Shah SA, Ali T, Chung JI, Kim MO. Anthocyanins Reversed D-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation Mediated Cognitive Impairment in Adult Rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2016:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9604-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kent K, Charlton K, Roodenrys S, Batterham M, Potter J, Traynor V. et al. Consumption of anthocyanin-rich cherry juice for 12 weeks improves memory and cognition in older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia. Eur J Nutr. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-1083-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Min J, Yu S-W, Baek S-H, Nair KM, Bae O-N, Bhatt A. et al. Neuroprotective effect of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside anthocyanin in mice with focal cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 2011;500(3):157–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sutton E, Thomas T, Bryant M, Landon C, Newton C, Rhodin J. Amyloid-beta peptide induced inflammatory reaction is mediated by the cytokines tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1999;31(3):313–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu Y, Ling W, Guo H, Song F, Ye Q, Zou T. et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of purified dietary anthocyanin in adults with hypercholesterolemia: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23(9):843–9. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.El Mohsen MA, Marks J, Kuhnle G, Moore K, Debnam E, Srai SK. et al. Absorption, tissue distribution and excretion of pelargonidin and its metabolites following oral administration to rats. Br J Nutr. 2006;95(01):51–8. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]