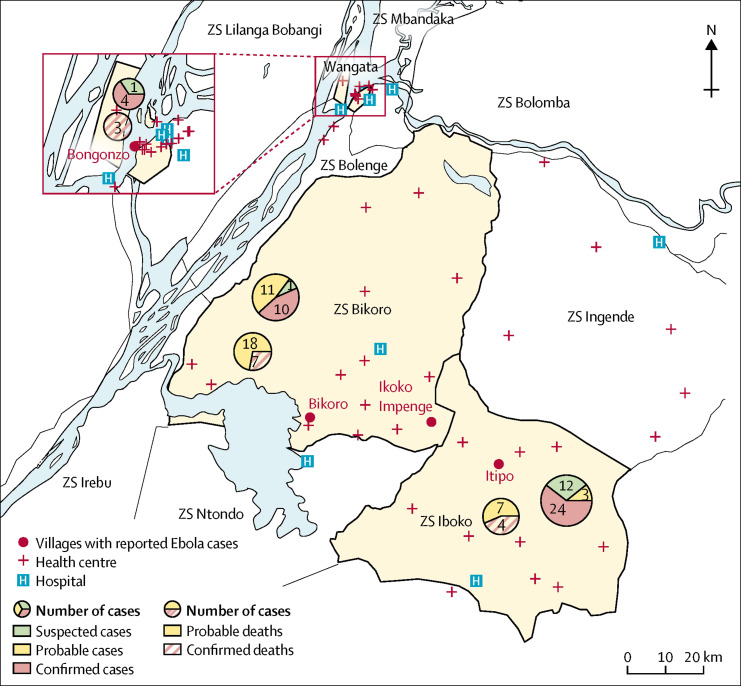

The unfolding outbreak of Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) dominated discussions at last month's World Health Assembly (WHA) in Geneva, Switzerland. Several funding pledges were made and WHO estimated that US$26 million will be required to control the outbreak.1 On May 8, 2018, the DRC Government declared an outbreak of Ebola virus disease, initially in a remote area of the Equateur Province (figure ).2 As of June 10, 2018, the Government of DRC reported 66 cases of Ebola virus disease and 28 deaths (case fatality rate 42·4%).3 Of the 66 cases, 38 were laboratory confirmed, 14 were probable where it was not possible to collect laboratory specimens for testing, and 14 were suspected. Of the confirmed and probable cases, 27 (52%) are from Iboko, 21 (40%) from Bikoro, and four (8%) from Wangata health zones. A total of five health-care workers have been affected, with four confirmed cases and two deaths.

Figure.

Cases distribution of Ebola virus disease outbreak in Equateur Province, DRC, as of June 10, 2018

The number of cases shown are as reported by the Ministry of Health, DRC, as of June 10, 2018. The map is adapted from one from the Ministry of Health DRC.

Although this is the ninth outbreak of Ebola virus disease in DRC since 1976, certain features of the current epidemic have caused serious concerns in the international community. First, four cases have been identified in Wangata, a district of Mbandaka, the capital of the Equateur Province with an estimated population of 1·2 million inhabitants. Thus, this is the first time the DRC Government and partners are tackling an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in an urban city. Second, the other epicentres of the Ebola virus disease outbreak are in rural remote areas: Bikoro and Iboko are located close to the River Congo, which serves the two neighbouring countries of the Central Africa Republic and the Republic of the Congo, creating an increased risk of the disease spreading to these countries if the outbreak is not rapidly controlled in DRC. The 2014–16 outbreak of Ebola virus disease in west Africa, which resulted in 11 310 deaths,4 showed how rapidly the disease could spread into neighbouring countries.

Although the outbreak of Ebola virus disease in DRC is ongoing, two features of the response are noteworthy: the swiftness of the response time and the introduction of ring vaccinations, an innovative, pre-emptive strategy to vaccinate those most at risk of infection. The global health community learned from the 2014–16 west Africa Ebola virus disease outbreak that a speedy response was vital to control the outbreak. The response to the current outbreak in DRC has been rapid at the national, continental, and international levels. The DRC Health Minister, Oly Ilunga Kalenga, has led his country's response with pragmatism and expediency, both in Kinshasa and at the provincial levels, by developing a comprehensive response plan and establishing appropriate technical committees and mobilising the requisite political, financial, and technical support.5

At the continental level, within 2 days of declaration of the outbreak the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), which one of us (JNN) leads, had activated its Emergency Operation Center in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; deployed an advance team of epidemiologists to Kinshasa to assist the Ministry of Heath; and briefed an extraordinary session of the Permanent Representative Committee of the 55 African Union member states. In addition, the Director of the Africa CDC (JNN) led a delegation to Kinshasa, Bikoro, and Mbandaka for an assessment of the gaps in the responses requiring support from Africa CDC. The Africa CDC team worked with the staff from WHO to assist the Ministry of Health to develop three strategies: surveillance and contact tracing; focal health-care zones to ensure adequate control measures; and laboratory testing. Africa CDC is also deploying more than 30 health-care workers, including epidemiologists, infection control and laboratory experts, and anthropologists.

Globally, WHO has had a crucial role by rallying appropriate attention to the outbreak and mobilising essential international partners to action. WHO has augmented the DRC Health Ministry's response plan by deploying many health-care workers in the field and is supporting a ring vaccination programme with a Merck-produced Ebola vaccine.6 The vaccination programme is led by DRC's Ministry of Health and supported by WHO and partners. This is the first time such a vaccine has been used outside of the west Africa 2014–16 epidemic. Importantly, the vaccine is being deployed as the outbreak unfolds as part of a new international approach for rapid mitigation of outbreaks through multiple interventions. Anthropological and sociological determinants of the uptake of the vaccination programme will be crucial as the intervention is scaled up. Moreover, issues of access, equity, and ethical considerations in deploying the vaccine will need to be considered. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) rapidly set up treatment and containment centres at the affected sites to minimise transmission and improve clinical outcomes for detected patients. Several other partners are assisting with the response, including the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, and others.

However, six important gaps in outbreak governance and logistics management must be addressed to ensure a more comprehensive response to the Ebola virus disease outbreak in DRC. The first is leadership of the response. Much has been learned from dealing with past outbreaks of Ebola virus disease in west Africa but each new outbreak has unique challenges. It is the responsibility of each country to ensure the health security of its citizens. However, effective leadership of the Government of DRC may be challenged given the weak health system of the country due to its long history of conflict and resulting economic and political difficulties. All efforts should be made to strengthen their leadership. As such, financial, human, and material assistance from the global community to DRC's leadership will be central to ensure an effective response. Second, coordination—but not control—of contributing partners' effort is essential to create efficiencies to control the outbreak. Third, translating global material and financial commitment into country-level disbursements must be accelerated. Fourth, commitments made to support the response in DRC must be fulfilled. There have been huge logistical challenges with airlifting supplies and health-care workers from Kinshasa to Mbandaka, Iboko, and Bikoro, because no commercial flights exist from Kinshasa to Mbandaka and motorable roads from Mbandaka to the other affected areas are non-existent. Although financial and material support was expressed at the WHA, ensuring that these commitments reach DRC in a timely way is not yet evident. Fifth, there has been inadequate support of the focal health-care zones (Bikoro, Iboko, Mbandaka, and Equateur Province) to establish appropriate control measures and minimise transmission. Finally, laboratory testing has been challenged by insufficient supplies and a shortage of experienced staff.

The outbreak of Ebola virus disease in DRC is far from over and may take several months to bring under control. The steps taken in the next few weeks will be crucial to the trajectory of the outbreak and it is vital that effective coordination of partners' efforts and rapid provision of requisite and well tested interventions are put in place. In this context, fiscal and infrastructural support to DRC will be important for rapid containment of the outbreak. As more partners join the fight to control this outbreak, standard operating procedures for engaging with the government, coordinating with other partners, allocating financial resources, and deployment in the field should be established quickly to ensure effective coordination, but not control, of partners' efforts. Such standard operating procedures for outbreak governance will ensure that aid is not a burden to DRC but an asset in the response.

Any successful public health response is based on trust between practitioners, patients, government, and communities. Trust is essential for effective outbreak control and must be underpinned by active case finding, contact tracing and follow-up, and engagement with communities. In addition, health-care infrastructure needs to be strengthened and supported to provide health care for non-Ebola patients. Strengthened health-care systems are needed to address existing endemic health challenges and respond to future Ebola outbreaks and other emerging infections in DRC.

Alongside the response to the outbreak, post-Ebola recovery plans for DRC must include supporting the country to develop a functional national public health institute. In future, the response to a potential tenth outbreak of Ebola virus disease in DRC must be led by the country's national public health institute. In November, 2002, an outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome caught China unprepared.7 In response to that outbreak, the Government of China established the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC). Today, if faced with a similar disease threat, China CDC, and not the international community, would lead the response in China. This is what should be done in DRC and all African countries. This is a vision Africa CDC and the African Union are promoting as a new public health order for Africa's health and economic security. To ensure that this vision is achieved, the African Union Commission and Africa CDC will be convening an International Conference on Ebola in DRC: Response in July, 2018, to raise funding and advocate for sustained support for the DRC's response efforts.

Acknowledgments

JNN is Director of Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and PO is senior adviser for policy and strategy in the office of the director at Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. We declare no other competing interests.

References

- 1.Baumgaertner E. As aid workers move to the heart of Congo's Ebola outbreak, “everything gets more complicated”. The New York Times. June 1, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/01/health/ebola-congo-outbreak.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green A. Ebola outbreak in the DR Congo: lessons learned. Lancet. 2018;391:2096. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health. DRC Government ECHOS Ebola RDC 2018. La situation épidémiologique de la Maladie à Virus Ebola. June 10, 2018. https://mailchi.mp/a56fd1304735/ebola_rdc_10juin

- 4.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html

- 5.WHO. Ministry of Health. Democratic Republic of the Congo Strategic response plan for the Ebola virus disease outbreak Democratic Republic of Congo. 2018. http://www.who.int/emergencies/crises/cod/DRC-ebola-disease-outbreak-response-plan-28May2018-ENfinal.pdf?ua=1&ua=1

- 6.Henao-Restrepo AM, Anton Camacho A, Longini IM. Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine in preventing Ebola virus disease: final results from the Guinea ring vaccination, open-label, cluster-randomised trial (Ebola Ça Suffit!) Lancet. 2017;389:505–518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32621-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z, Gao GF. Infectious disease trends in China since the SARS outbreak. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:1113–1115. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30579-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]