On May 23, 2005, the 58th World Health Assembly, consisting of the 192 Member States of WHO, adopted the revised International Health Regulations (IHR), the code of international regulations for the control of transboundary infectious diseases.1 The spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome illustrated the rapidity with which a new infectious disease can spread and affect today's interconnected world. The deliberate release of anthrax in the aftermath of the events of Sept 11, 2001, highlighted another dimension of microbial threats. Neither event was adequately addressed in the previous IHR of 1969.2

The key constraints of IHR (1969) were the limited scope of diseases (cholera, plague, yellow fever), the dependence on official notification to WHO by affected countries, the scarcity of mechanisms for collaboration in investigating such outbreaks, and the lack of specific risk-reduction measures to prevent the international spread of disease. Indeed, there was disincentive to reporting under the IHR because unaffected countries applied travel and trade restrictions far in excess of the true risks of the disease. The new IHR 2005 goes some way toward addressing these issues by establishing expert panels to review the risks to international public health and recommend evidence-based control measures. However, even the revised IHR show an inevitable compromise between national sovereignty and the collective international good; of trying to ensure the maximum security against the international spread of disease with minimum interference to travel and trade.

New infectious diseases have been emerging at the unprecedented rate of about one a year for the past two decades, a trend that is expected to continue.3, 4 In the past 10 years, new and emerging infectious diseases with a potential threat to international public health include Ebola, Lassa, and Marburg haemorrhagic fevers in Africa, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in Europe, meningococcal meningitis W135 associated with returning Hajj pilgrims, Nipah virus in Malaysia, West Nile virus in the Americas, severe acute respiratory syndrome, and the pandemic threat from avian influenza H5N1 in Asia.

There is clearly a need for new approaches to confront these emerging threats from infectious disease. In 2000, the WHO Department of Communicable Diseases Surveillance and Response in Geneva initiated the formation of the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN),5 which provides the operational and technical response arm for control of global outbreaks. In 2000–04, GOARN responded to 34 events in 26 countries, and has grown to a partnership of over 120 institutions and networks, including UN and intergovernmental organisations. The Network provided substantial support to affected countries during the outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome and in response to avian influenza. It was clear that the IHR (1969) also needed to change to allow response to contemporary threats to international health. Efforts towards achieving this response began in 1995.6

The purpose and scope of the IHR (2005) are to prevent, protect against, control, and provide a public-health response to the international spread of disease in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public-health risks, while avoiding unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade. The IHR (2005) affirm the continuing importance of WHO's role in global outbreak alert and response to public-health events. The revised IHR spell out the responsibilities for WHO, other international agencies with a mandate to protect public health (including radiation health and chemical safety), and the Member States themselves.

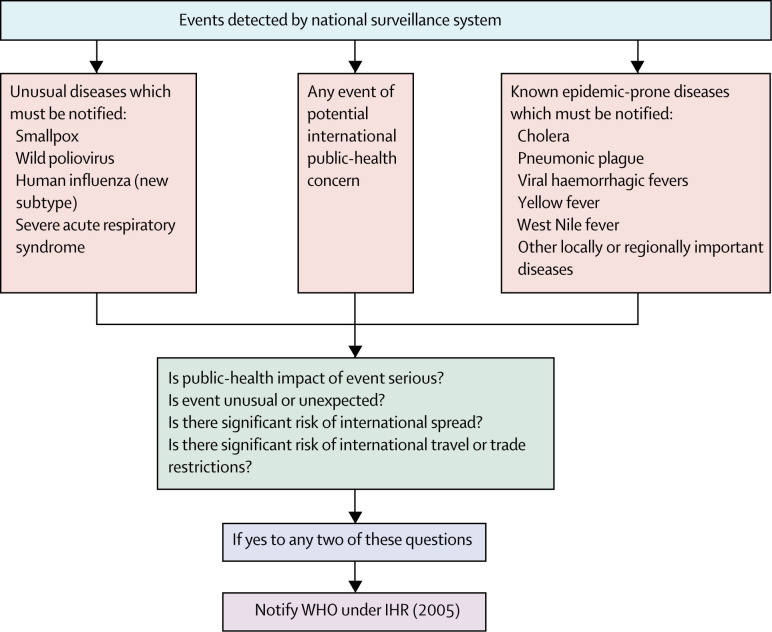

A decision instrument has been developed to assist countries in determining whether an unexpected or unusual public-health event within its territory, irrespective of origin or source, might constitute a public-health emergency of international concern and require notification to WHO. Criteria include morbidity, mortality, whether the event is unusual or unexpected, its potential to have a major public-health effect, whether external assistance is needed to detect, investigate, respond, and control the current event, if there is a potential for international spread, or if there is a significant risk to international travel or trade.

The IHR (2005) explicitly recognise the need for intersectoral and multidisciplinary cooperation in managing risks of potential international public-health importance. Key partners include intergovernmental organisations or international bodies with which WHO is expected to cooperate and coordinate its activities: eg, the UN, International Labour Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization, International Atomic Energy Agency, International Civil Aviation Organization, International Committees and Federations of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, and Office International des Epizooties.

The revised IHR set out core capacities of a country's preparedness to detect and respond to health threats—early warning and routine surveillance systems, epidemiological and outbreak investigation skills, laboratory expertise, information and communication technologies, and management systems. WHO will continue its traditional role of providing support for national capacity building to achieve these core capacities.

A short list of diseases (figure ) needing mandatory notification to WHO are included in the decision instrument; however, countries are now also required to assess the international public-health threat posed by any unusual health event, including those of unknown causes or sources, and outbreaks caused by agents with the known ability to cause serious public-health effect and to spread rapidly internationally. Importantly, WHO can now use a range of sources of health intelligence to raise an alarm and begin a process of verification with countries that have not voluntarily reported significant health events. Parties capitalised to the IHR are required to inform WHO within 24 h of the receipt of evidence of a public-health risk that might cause international spread of a disease. Finally, if WHO obtains credible evidence that a public-health event of international importance has occurred and fails to obtain disclosure and cooperation by the affected state, it has discretionary power to release the public-health information required to protect global public health.

Figure.

Simplified decision instrument for assessment and notification of events that might constitute public-health emergency of international concern under International Health Regulations (2005)

The IHR work on the principle of global public good—protecting public health through early detection and response to public-health emergencies benefits the nation concerned and reduces the risks of spread to other nations.7 Their impact will be limited unless national governments accept their global public-health responsibilities. Furthermore, because most human emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic in origin, there is a need for close collaboration between the veterinary, human health, and wildlife sectors.8 The regulations of the Office International des Epizooties, the veterinary counterpart of the IHR, face similar challenges as did the IHR (1969), and perhaps need a similar overhaul. The problems currently faced in confronting the threat to human and animal health posed by the outbreaks of avian influenza A H5N1 in Asia amply illustrate this contention. The IHR (2005) will enter into force in 2007.

Acknowledgments

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Fifty-eighth World Health Assembly Resolution WHA58.3: revisions of the International Health Regulations. 23 May, 2005. http://www.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA58/WHA58_3-en.pdf (accessed June 10, 2005)

- 2.World Health Organization . International Health Regulations (1969). Third annotated edition. WHO; 1983. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/1983/9241580070.pdf (accessed June 10, 2005) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smolinksi MS, Hamburg MA, Lederberg J, editors. Microbial threats to health: emergence, detection and response. The National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Fifty-fourth World Health Assembly Resolution WHA54.14 Global health security: epidemic alert and response. 21 May 2001. http://www.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA54/ea54r14.pdf (accessed June 10, 2005)

- 5.World Health Organization WHO/CDS/CSR/2000.3. Global outbreak alert and response: report of a WHO meeting Geneva, Switzerland April 26–28, 2000. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/surveillance/whocdscsr2003.pdf (accessed June 10, 2005)

- 6.World Health Organization Fifty-first World Health Assembly. Revision of the International Health Regulations: progress report. Report by the Director General. A51/8. March 10, 1998. http://ftp.who.int/gb/pdf_files/WHA51/ea8.pdf (accessed June 10, 2005)

- 7.Smith R, Beaglehole R, Woodward D, Drager N, editors. Global public goods for health: health economics and public health perspectives. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fouchier R, Kuiken T, Rimmelzwaan G, Osterhaus A. Global task force for influenza. Nature. 2005;435:419–420. doi: 10.1038/435419a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]