Abstract

Background

Partner notification (PN) is the process whereby sexual partners of an index patient are informed of their exposure to a sexually transmitted infection (STI) and the need to obtain treatment. For the person (index patient) with a curable STI, PN aims to eradicate infection and prevent re‐infection. For sexual partners, PN aims to identify and treat undiagnosed STIs. At the level of sexual networks and populations, the aim of PN is to interrupt chains of STI transmission. For people with viral STI, PN aims to identify undiagnosed infections, which can facilitate access for their sexual partners to treatment and help prevent transmission.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different PN strategies in people with STI, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Search methods

We searched electronic databases (the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE and EMBASE) without language restrictions. We scanned reference lists of potential studies and previous reviews and contacted experts in the field. We searched three trial registries. We conducted the most recent search on 31 August 2012.

Selection criteria

Published or unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs comparing two or more PN strategies. Four main PN strategies were included: patient referral, expedited partner therapy, provider referral and contract referral. Patient referral means that the patient notifies their sexual partners, either with (enhanced patient referral) or without (simple patient referral) additional verbal or written support. In expedited partner therapy, the patient delivers medication or a prescription for medication to their partner(s) without the need for a medical examination of the partner. In provider referral, health service personnel notify the partners. In contract referral, the index patient is encouraged to notify partner, with the understanding that the partners will be contacted if they do not visit the health service by a certain date.

Data collection and analysis

We analysed data according to paired partner referral strategies. We organised the comparisons first according to four main PN strategies (1. enhanced patient referral, 2. expedited partner therapy, 3. contract referral, 4. provider referral). We compared each main strategy with simple patient referral and then with each other, if trials were available. For continuous outcome measures, we calculated the mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For dichotomous variables, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI. We performed meta‐analyses where appropriate. We performed a sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome re‐infection rate of the index patient by excluding studies with attrition of greater than 20%. Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias and extracted data. We contacted study authors for additional information.

Main results

We included 26 trials (17,578 participants, 9015 women and 8563 men). Five trials were conducted in developing countries. Only two trials were conducted among HIV‐positive patients. There was potential for selection bias, owing to the methods of allocation used and of performance bias, owing to the lack of blinding in most included studies. Seven trials had attrition of greater than 20%, increasing the risk of bias.

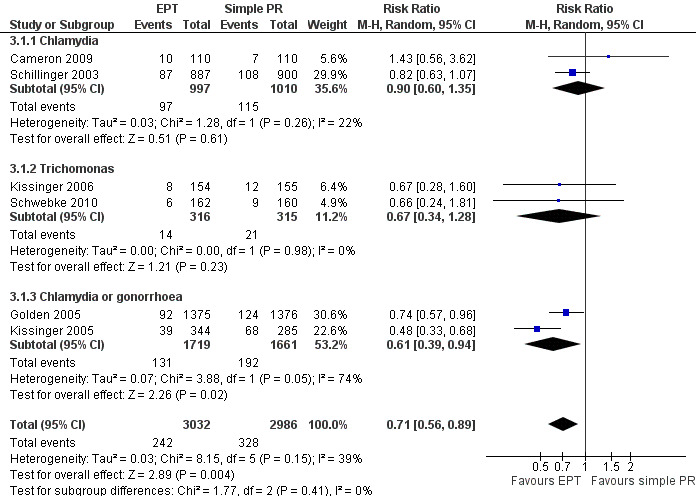

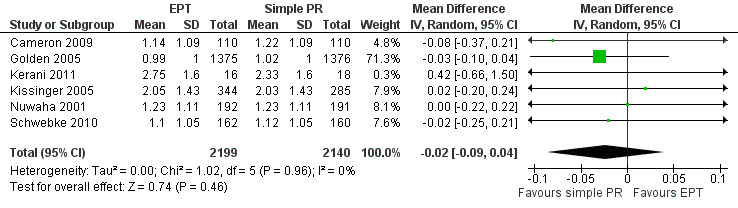

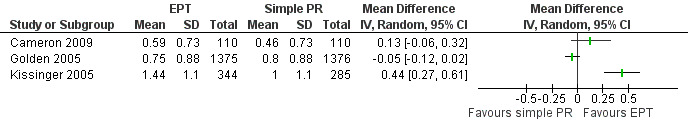

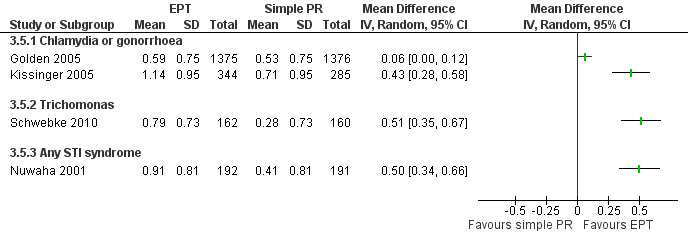

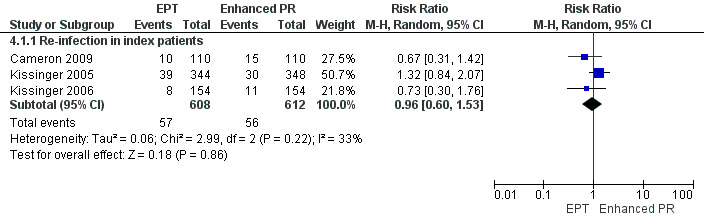

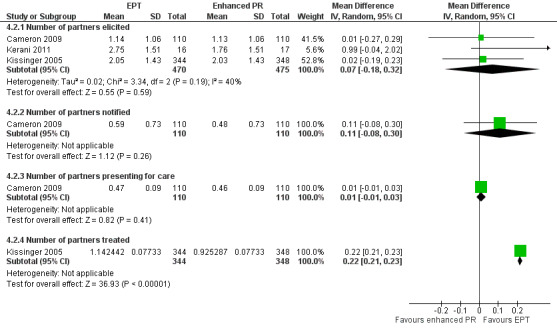

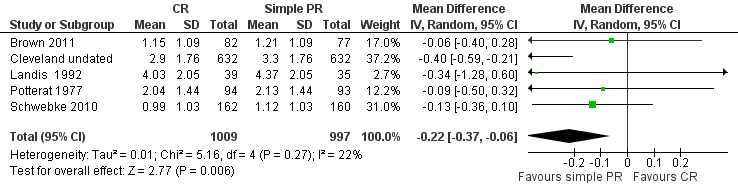

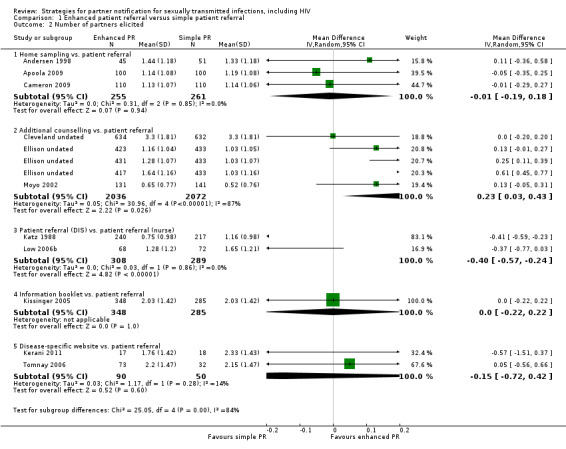

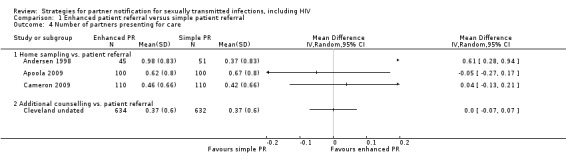

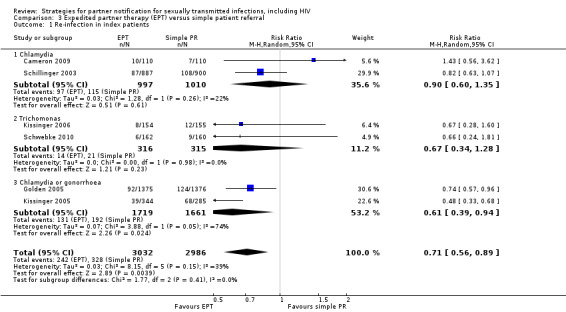

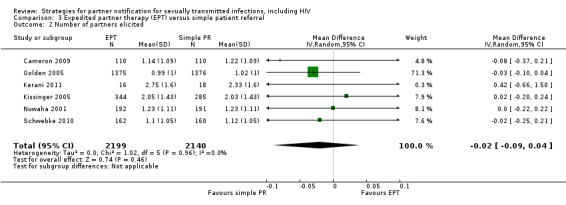

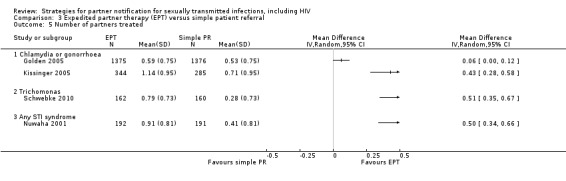

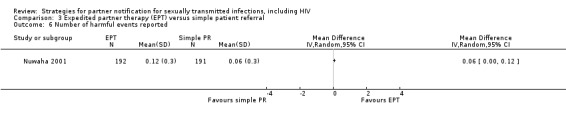

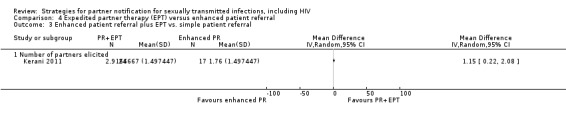

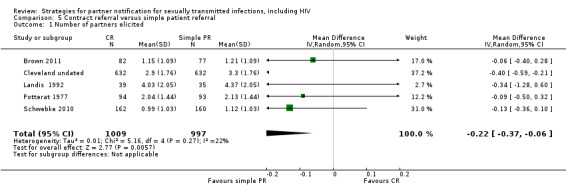

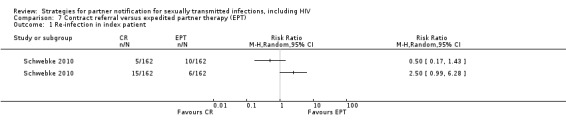

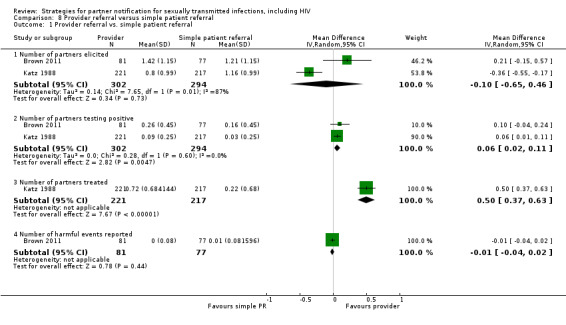

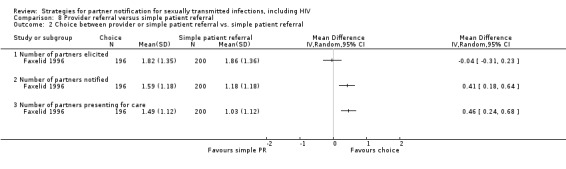

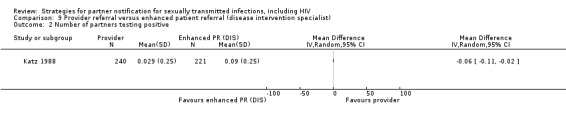

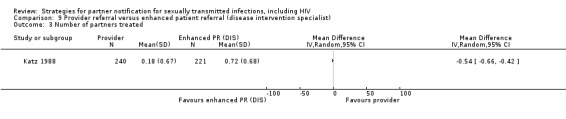

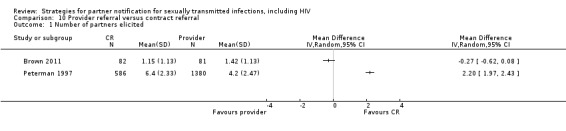

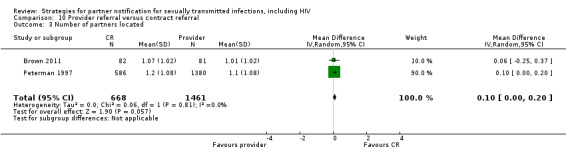

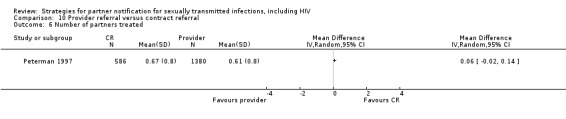

The review found moderate‐quality evidence that expedited partner therapy is better than simple patient referral for preventing re‐infection of index patients when combining trials of STIs that caused urethritis or cervicitis (6 trials; RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.89, I2 = 39%). When studies with attrition greater than 20% were excluded, the effect of expedited partner therapy was attenuated (2 trials; RR 0.8, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.04, I2 = 0%). In trials restricted to index patients with chlamydia, the effect was attenuated (2 trials; RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.35, I2 = 22%). Expedited partner therapy also increased the number of partners treated per index patient (three trials) when compared with simple patient referral in people with chlamydia or gonorrhoea (MD 0.43, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.58) or trichomonas (MD 0.51, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.67), and people with any STI syndrome (MD 0.5, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.67). Expedited partner therapy was not superior to enhanced patient referral in preventing re‐infection (3 trials; RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.53, I2 = 33%, low‐quality evidence). Home sampling kits for partners (four trials) did not result in lower rates of re‐infection in the index case (measured in one trial), or higher numbers of partners elicited (three trials), notified (two trials) or treated (one trial) when compared with simple patient referral. There was no consistent evidence for the relative effects of provider, contract or other patient referral methods. In one trial among men with non‐gonococcal urethritis, more partners were treated with provider referral than with simple patient referral (MD 0.5, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.63). In one study among people with syphilis, contract referral elicited treatment of more partners than provider referral (MD 2.2, 95% CI 1.95 to 2.45), but the number of partners receiving treatment was the same in both groups. Where measured, there was no statistical evidence of differences in the incidence of adverse effects between PN strategies.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence assessed in this review does not identify a single optimal strategy for PN for any particular STI. When combining trials of STI causing urethritis or cervicitis, expedited partner therapy was more successful than simple patient referral for preventing re‐infection of the index patient but was not superior to enhanced patient referral. Expedited partner therapy interventions should include all components that were part of the trial intervention package. There was insufficient evidence to determine the most effective components of an enhanced patient referral strategy. There are too few trials to allow consistent conclusions about the relative effects of provider, contract or other patient referral methods for different STIs. More high‐quality RCTs of PN strategies for HIV and syphilis, using biological outcomes, are needed.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Male, Chlamydia Infections, Chlamydia Infections/therapy, Chlamydia Infections/transmission, Contact Tracing, Contact Tracing/methods, Gonorrhea, Gonorrhea/therapy, Gonorrhea/transmission, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Sexual Partners, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Sexually Transmitted Diseases/prevention & control, Sexually Transmitted Diseases/transmission, Urethritis, Urethritis/therapy, Uterine Cervicitis, Uterine Cervicitis/therapy

Plain language summary

Strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

Sexually transmitted infections (STI) are a major global cause of acute illness, infertility and death. Every year there are an estimated 499 million new cases of the most common curable STIs (trichomoniasis, chlamydia, syphilis and gonorrhoea), and between two and three million new cases of HIV. The presence of several STIs, including syphilis and herpes can increase the risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV.

Partner notification (PN) is a process whereby sexual partners of patients given a diagnosis of STI are informed of their exposure to infection and the need to receive treatment. PN for curable STI may prevent re‐infection of the patient and reduce the risk of complications and further spread.

A review update of the research of the strategies of partner notification in people with STI, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection was conducted by researchers in the Cochrane Collaboration. After searching for all relevant studies, they found 26 studies. This review covers four main PN strategies: 1) Patient referral means that the patient tells their sexual partners that they need to be treated, either with (enhanced) or without (simple) additional support to enhance outcomes. 2) Expedited partner therapy means that the patient delivers medication or a prescription for medication to their partner(s) without the need for a medical examination of the partner. 3) Provider referral means that health service personnel notify the partners. 4) Contract referral means that the patient is encouraged to notify partners but health service personnel will contact them if they do not visit the health service by a certain date.

The 26 trials in this review included 17,578 participants. Five trials were conducted in developing countries and only two trials were performed among HIV‐positive patients. Expedited partner therapy was more successful than simple patient referral in reducing repeat infection in patients with gonorrhoea, chlamydia or non‐gonococcal urethritis (six trials). Expedited partner therapy and enhanced patient referral resulted in similar levels of repeat infection (three trials). Evidence about the effects of home sampling, where patients with chlamydia received a sample kit for the partner, was inconsistent (three trials). There were too few trials to allow consistent conclusions about the relative effects of provider, contract or other patient referral methods for different STIs. More studies need to be performed on HIV and syphilis and harms need to be measured and reported.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Enhanced patient referral compared with simple patient referral for partner notification for STIs, including HIV.

| Enhanced patient referral compared with simple patient referral for partner notification for STIs, including HIV | ||||||

| Health problem: partner notification for STIs, including HIV Settings: people in rural and urban areas, given a diagnosis of STI (clinically or by a laboratory) in health services Intervention: enhanced patient referral Comparison: simple patient referral | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Simple patient referral | Enhanced patient referral | |||||

| Re‐infection in index patient ‐ home sampling vs. simple patient referral Follow‐up: 12 months | Study population | RR 2.14 (0.91 to 5.05) | 220 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 64 per 1000 | 136 per 1000 (58 to 321) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 64 per 1000 | 137 per 1000 (58 to 323) | |||||

| Re‐infection in index patient ‐ information booklet vs. simple patient referral Follow‐up: 8 weeks | Study population | RR 0.55 (0.22 to 1.33) | 942 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | ||

| 180 per 1000 | 99 per 1000 (40 to 239) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 156 per 1000 | 86 per 1000 (34 to 207) | |||||

| Re‐infection in index patient ‐ patient referral (DIS/health advisor) vs. patient referral (nurse) Follow‐up: 6 weeks | Study population | RR 0.35 (0.01 to 8.51) | 140 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5 | ||

| 14 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (0 to 118) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 14 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (0 to 119) | |||||

| Re‐infection in index patient ‐ disease‐specific website vs. simple referral Follow‐up: 1 weeks | Study population | RR 3.12 (0.17 to 58.73) | 105 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Re‐infection in index patient ‐ additional counselling vs. simple patient referral Follow‐up: 6 months | Study population | RR 0.49 (0.27 to 0.89) | 600 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate7 | ||

| 101 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 (27 to 90) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 101 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (27 to 90) | |||||

| The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; DIS: disease intervention specialist; RR: risk ratio; STI: sexually transmitted infection. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Method of allocation concealment was not reported. 70% completed follow‐up, some were lost to follow‐up and some withdrew from the study, reasons for withdrawal were not reported. Study was not blinded. 2 Assuming alpha of 0.05 and beta of 0.2. For relative risk reduction of 20% with best estimate of control event rate of 0.2 approximately 3000 participants were required. The total sample size was 220 and did not meet the optimal information size. 3 High attrition rate and no information given on method of allocation concealment in one of the studies. Different methods were used for outcome assessment 4 I2 = 76% (P value = 0.06) and minimal overlap of CIs. 5 Sample size less than 400, there were very few events and CIs around both relative and absolute estimates include both appreciable benefit and appreciable harm. 6 Sample size was very small and optimal information size was not met. There were very few events and CIs overlapped, therefore, no effect both for absolute and relative estimates. 7 Risk for selective reporting and unclear method of allocation concealment.

Summary of findings 2. Expedited partner therapy compared with simple patient referral for partner notification for STIs, including HIV.

| Expedited partner therapy compared with simple patient referral for partner notification for STIs, including HIV | ||||||

| Health problem: partner notification for STIs, including HIV Settings: people in rural and urban areas, given a diagnosis of STI (clinically or by a laboratory) in health services Intervention: expedited partner therapy Comparison: simple patient referral | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Simple patient referral | EPT | |||||

| Re‐infection in index patients Follow‐up: 2‐12 months | Study population | RR 0.71 (0.56 to 0.89) | 6018 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 110 per 1000 | 78 per 1000 (62 to 98) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 84 per 1000 | 60 per 1000 (47 to 75) | |||||

| Re‐infection in index patients ‐ chlamydia Follow‐up: 3‐12 months | Study population | RR 0.9 (0.6 to 1.35) | 2007 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

| 114 per 1000 | 102 per 1000 (68 to 154) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 92 per 1000 | 83 per 1000 (55 to 124) | |||||

| Re‐infection in index patients ‐ trichomonas | Study population | RR 0.67 (0.34 to 1.28) | 631 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | ||

| 67 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (23 to 85) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 67 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (23 to 86) | |||||

| Re‐infection in index patients ‐ chlamydia or gonorrhoea Follow‐up: 4‐18 weeks | Study population | RR 0.61 (0.39 to 0.94) | 3380 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,6 | ||

| 116 per 1000 | 71 per 1000 (45 to 109) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 164 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (64 to 154) | |||||

| The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 There was high attrition rate in three of the studies. Methods of sequence generation and allocation concealment not reported in two of the studies. 2 CI includes possibility of no effect (i.e. RR of 1.0). 3 Method of sequence generation and allocation concealment not reported in one of the studies. There was high attrition rate in one of the studies. 4 Sample size was greater than 400 but CI overlaps, therefore, no effect (i.e. RR of 1.0). 5 There were no details on method of sequence generation and allocation concealment. One of the studies had a high attrition rate. 6 I2 = 74%

Summary of findings 3. Expedited partner therapy compared with enhanced patient referral for partner notification for STIs, including HIV.

| Expedited partner therapy compared with enhanced patient referral for partner notification for STIs, including HIV | ||||||

| Health problem: partner notification for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV Settings: people in rural and urban areas, given a diagnosis of STI (clinically or by a laboratory) in health services Intervention: expedited partner therapy Comparison: enhanced patient referral | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Enhanced patient referral | EPT | |||||

| EPT vs. enhanced patient referral ‐ re‐infection in index patients Follow‐up: 1‐12 months | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.6 to 1.53) | 1220 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 92 per 1000 | 88 per 1000 (55 to 140) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 86 per 1000 | 83 per 1000 (52 to 132) | |||||

| The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; EPT: expedited partner therapy; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 No details on method of sequence generation in one of the studies. One study had high attrition rate and one study used different methods for outcome assessment. 2 Sample size is high but CI includes appreciable benefit and harms with both relative risk reduction and increase being greater than 25%.

Summary of findings 4. Contract referral compared with expedited partner therapy for partner notification for STIs, including HIV.

| Contract referral compared with expedited partner therapy for partner notification for STIs, including HIV | ||||||

| Health problem: partner notification for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV Settings: people in rural and urban areas, given a diagnosis of STI (clinically or by a laboratory) in health services Intervention: contract referral Comparison: expedited partner therapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| EPT | Contract referral | |||||

| Re‐infection in index patient Follow‐up: 3 months | Study population | RR 2 (0.7 to 5.72) | 322 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 99 per 1000 | 198 per 1000 (69 to 565) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 99 per 1000 | 198 per 1000 (69 to 566) | |||||

| The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Method of sequence generation and allocation concealment not reported. The study had high attrition rate. No blinding. 2 Imprecision owing to small sample size.

Background

Description of the condition

Sexually transmitted infections (STI) have a negative impact on the social, health and economic well‐being of a country. Every year an estimated 499 million new cases of the four most common curable STI, trichomoniasis, chlamydia, syphilis and gonorrhoea, are acquired (WHO 2012). Furthermore, two to three million new cases of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) occur per year (UNAIDS 2010). Up to 4000 infants become blind annually due to eye infections attributable to underlying gonococcal and chlamydial infections in the mother (WHO 2007).

The term STI includes both infections that remain latent or asymptomatic and those that progress to a clinical manifestation (disease). In this update, we used the term STI instead of sexually transmitted diseases (STD), which was used in the original review. STI are more prevalent in countries and communities where socio‐economic conditions are poor (Glasier 2006; Low 2006a). Curable STIs are often overshadowed by the burden of HIV, but are important causes of morbidity in their own right (Table 5).

1. Burden of disease.

| Disease | DALYs |

| HIV | 58.5 million |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | 3.7 million |

| Gonorrhoea | 3.5 million |

| Other | 280,000 |

Source: WHO 2004.

DALY: disability adjusted life years.

Clinical symptoms of STIs can be non‐specific and, where possible, the diagnosis needs to be confirmed by laboratory testing. In lower‐income countries, laboratory testing is not always available and women and men reporting symptoms suggestive of an STI are often treated according to algorithms without confirmatory tests. For male urethritis and genital ulcers, this approach is effective but with vaginal discharge the risk of misdiagnosis is high. Syndromic management of STI can therefore lead to over‐treatment and adverse social consequences such as stigma and intimate partner violence (Trollope‐Kumar 2006). Women are more likely than men to suffer from reproductive tract complications of STIs such as chlamydia and gonorrhoea if the infection ascends to the upper genital tract; pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ectopic pregnancies and infertility are the most commonly documented complications (Gerbase 1998). STIs are, however, often asymptomatic in both women and men (WHO 2007). As a result, disclosing a diagnosis of an STI to sexual partners and partner treatment play a critical part in the comprehensive management of STI. Willingness to disclose varies according to the STI and gender (Alam 2010). In one study among people with a diagnosis of HIV, 85% of people living with HIV were sexually active, but only 58% revealed their HIV status to recent sexual partners (Simbayi 2007). In a study in Connecticut, US, 25% of females with chlamydia intended not to notify their partners (Niccolai 2007) as most (46%) thought it unimportant and 43% were not willing to discuss the condition. In a study in India, the patient characteristics most likely to increase the odds of referring a partner were having a diagnosis of genital ulcer disease (odds ratio (OR) 2.78, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.08 to 7.13, P value = 0.033) and having the intention to inform the regular partners (OR 16.9, 95% CI 3.29 to 86.70, P value = 0.001) (Sahasrabuddhe 2002).

Description of the intervention

"Partner notification is a process that includes informing sexual partners of infected people of their exposure, administering presumptive treatment, and providing advice about the prevention of future infection" (UNAIDS 1999). Partner notification (PN) is also known as contact tracing, partner management or partner information. A person with a newly diagnosed STI is often referred to as an 'index case' or 'index patient'. The index patient has one or more sexual partners. The sexual partners of the index patient might have been the source of the infection in the index patient or they might have acquired the infection from the index patient.

A variety of approaches has been used to notify sexual partners and to ensure that they receive treatment. In principle, managing infection in people with more than one current sexual partner should have the greatest impact on the spread of STI (Fenton 1997). The use of different approaches depends partly on the STI for which they were originally intended. There are other influences at the country level, including cultural factors, the structure and financing of health systems, and clinical consensus. At the individual level, factors such as patient choice influence choice of PN strategies. Traditionally, three main approaches have been defined: patient referral, provider referral and contract (or conditional) referral. Definitions and explanations of these PN methods are given below.

Patient referral (patient‐led referral) refers to an approach in which health service personnel encourage index patients to notify their own partners. In this review, we used the term simple patient referral to refer to spoken advice from health service personnel about the need for sexual partners to receive treatment. This can be seen as a minimum standard for a PN intervention. There is, however, no agreement about the content of a consultation for simple patient referral. Patient referral was developed in the 1970s when rates of gonorrhoea in the US were very high and the capacity of specialist PN personnel was exceeded. Patient referral has since become the preferred method of PN for gonorrhoea and subsequently chlamydia in many countries. There has been great interest in developing methods to support index patients so that the outcomes of patient referral can be improved or enhanced (Trelle 2007). Patient referral can, therefore, be split into two categories (simple and enhanced), according to the level of support given to the patient. Expedited partner therapy (EPT) has developed in the US since the late 1990s as a new patient‐led strategy to help index patients to get their partners treated more quickly.

Enhanced patient referral refers to a group of strategies that supplement the spoken advice with the aim of improving patient referral success, including educational material such as videos viewed in waiting rooms, written disease‐specific information for index patients to give to their partners, home sampling kits for partners, disease‐specific websites, theory‐based counselling and reminders by telephone or other means (Trelle 2007).

EPT is a group of strategies to enhance the success of patient referral by increasing the numbers of partners treated and speeding up the time to treatment (CDC 2006). The EPT strategies include: patient‐delivered partner medication (PDPM) or patient‐delivered partner therapy (PDPT), where the index patient receives antibiotics (often in a package with condoms and written information) to give to their partner without the need for a medical examination of the partner (Golden 2005); or additional prescriptions given to index patients for their partner(s). EPT can reduce loss to follow‐up of index cases (Young 2007), and reduce the risk of repeated infection in the index case (Golden 2005). There are, however, disadvantages, including the risk of adverse drug reactions, other underlying disease remaining undetected and a missed opportunity for counselling and testing for other STIs including HIV (Golden 2005). In some countries, such as the UK, EPT is not legal unless the partner is assessed before receiving antibiotic treatment (ECDC 2013).

Provider referral (provider‐led referral) uses third parties (usually specialist health service personnel) to notify partners. The name of these health professionals differs between countries, for example; 'disease intervention specialists' (DIS) in the US; 'health advisers' in the UK and 'Kurators' in Sweden. Provider referral originated in Scandinavia and the UK as a method to trace and refer the sexual partners of people with syphilis when treatment first became available. More recently, it has been used for other clinically severe STIs such as HIV infection and hepatitis B. It can also be used for other STIs such as gonorrhoea and chlamydia when the index patient is unable to notify partners by themselves. Provider referral should only be done with the explicit consent of the index patient. In some countries, for example France, provider referral does not occur because it is seen as an invasion of privacy (ECDC 2013).

Contract referral (conditional referral) refers to an approach in which there is an agreement (contract) between the patient and the health professional. Health service personnel encourage index patients to notify their partners, with the understanding that health service personnel will notify those partners who do not visit the health service by an agreed date. Contract referral is, in practice, difficult to define as a separate PN approach. It can be difficult to distinguish from provider referral if the time window for patient referral is very short (two or three days) (Peterman 1997). In contrast, contract referral is often used as an extension to simple patient referral, rather than a separate strategy, if the index patient has not been able to inform their partner(s) when they are followed up.

How the intervention might work

There are different aims of PN, depending on the level at which it is targeted and the infection (Low 2006a). At the level of the index patient with a curable STI the aim is to provide concurrent antibiotic treatment to the sexual partner(s) so that infection can be eradicated in both people and re‐infection prevented in the index patient, which is a clinical goal. For the sexual partner(s) the aim is to identify and treat infection that might have been the source of infection in the index patient, or might have been acquired from the index patient. At the level of sexual networks and populations, the aim is to interrupt chains of transmission and reduce the spread of STIs, which is a public health goal. For viral STIs, the aim is to identify previously undiagnosed infections, which can provide early access for sexual partners to treatment and prevent onward transmission through behavioural change by the infected person.

To succeed, PN strategies need to first elicit from the index patient details of all sexual partners from whom he/she may have acquired the infection, or whom he/she might have subsequently infected. Identifying partners in the latent period of infection (usually three months for primary syphilis and one month for acute urethritis) (Toomey 1996), should identify those from whom infection was acquired, while identifying partners after the onset of symptoms will identify those who were likely to have been infected by the index case. The time period for identifying partners differs between countries for different STIs.

For most PN strategies, eliciting partner information from infected people is a prerequisite to notifying sexual partners. For example, when health service personnel notify partners, they rely on the index patient to count, name and provide details to enable all his/her partners to be traced. Once partners have been elicited, PN strategies need to provide either the index patient or the health service personnel with the necessary knowledge, skills or resources to enable them to locate, notify, medically evaluate and test or treat these partners.

Communication between partners, during which the index patient encourages them to consider screening or treatment, has been identified as a critical point in effective PN strategies (Young 2007). The communication usually requires the index patient to disclose their STI diagnosis. Disclosure can lead to benefits other than successful partner treatment, such as emotional support and protecting the health of others. Disclosure can also lead to stigma, rejection, physical abuse and discrimination (Arnold 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

PN has been practised as a measure to control STIs since the early 1900s (ECDC 2013), but there is limited evidence of its public health impact. Many evaluations have not been conducted as randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and many were conducted in developed countries before the HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic. It is not known whether interventions developed for high‐income countries are applicable to resource‐limited settings.

There are several published systematic reviews of PN. The first included only studies conducted in developed countries (Oxman 1994). Another included only published studies conducted in the US after 1980 (Macke 1999). The original Cochrane Review by Mathews et al. was assessed as up to date in July 2001 (Mathews 2001). Trelle et al. systematically reviewed studies of enhanced methods of patient referral, including EPT, to improve the effectiveness of simple patient referral (Trelle 2007). The latest systematic review only studied curable STIs in developing countries (Alam 2010). Considering the ongoing developments in this field, the Cochrane Review was updated in line with recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Objectives

To assess the effects of alternative PN strategies.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs that compared at least two PN strategies.

Types of participants

People in rural and urban areas, given a diagnosis of STI (clinically or by a laboratory) in health services with any of the following STI: gonorrhoea (Neisseria gonorrhoeae), chlamydia (Chlamydia trachomatis), trichomoniasis (Trichomonas vaginalis), syphilis (Treponema pallidum), chancroid (Haemophilus ducreyi), genital herpes, hepatitis B and HIV. We also included diagnoses of the following STI syndromes: genital ulcer syndrome ‐ non‐vesicular or vesicular, urethral discharge syndrome, vaginal discharge syndrome and lower abdominal pain in women. Studies conducted in any type of health service were included.

Types of interventions

Strategies directed at patients (patient‐led) or health workers (provider‐led) were included. The following types of strategies were included:

strategies to enhance the effectiveness of patient referral through, for example, health education and counselling, health education materials (such as pamphlets, posters, video and audio productions), patient assistance strategies directed at facilitating patient referral (such as referral cards, incentives, reminders, video and audio productions). EPT was included as a specific type of enhanced patient referral;

contract referral strategies;

provider referral strategies;

combinations of the above.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Number of index patients with curable STIs given a clinical or laboratory diagnosis of re‐infection. Re‐infection implies re‐infection of the index patient with the same STI from an untreated sexual partner. In practice, the outcome measured is repeated detection of the STI at some time interval after the index case has been treated. Repeated detection of an STI could also result from a new infection in the index case acquired from a new sexual partner, or treatment failure due to antibiotic resistance or subtherapeutic dosing. These causes cannot be reliably distinguished and the term re‐infection is used to include repeated detection from any cause.

Secondary outcomes

Numbers of partners elicited (sexual partners that the health professional obtains from the index patient for the recall period in question), located (sexual partners that the index patient was able to find; this number is likely to be a subset of partners elicited), notified (sexual partners that the index patient informed of their possible exposure to an STI; this number is likely to be a subset of partners located), presenting for care, testing positive or treated per index case; delay in partners presenting for care; incidence of STIs; changes in the index patient's or partner's behaviour with regard to condom use, abstinence in the presence of symptomatic infections, the number of partners, the number of concurrent partners; emotional impact on the index patient or partner in their relationship; harm to the patient or partners, such as domestic violence, abuse or suicide; ethical outcomes (patient autonomy vs. beneficence).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Search method for original review (Mathews 2001)

The original review authors searched MEDLINE (1966 to 24 July 2001), EMBASE (1974 to 24 July 2001), Psychological Abstracts (1967 to 24 July 2001) and Sociological Abstracts (1963 to 24 July 2001). The Cochrane Controlled Trials register was searched with the text words 'sexual partners', 'partner notification', 'contact‐tracing' and 'contact tracing'. The Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) register of studies was searched, as was the register of the HIV and AIDS Cochrane Review Group.

Search method for the review update

We searched three electronic databases, MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL, from 5 January 2001 to 31 August 2012. Search strategies are shown in Appendix 1, Appendix 2 and Appendix 3.

Searching other resources

Original Cochrane review (Mathews 2001)

The original review authors handsearched the Proceedings of the International AIDS Conferences (1996 to 24 July 2001) and the International Society for STD Research meetings (ISSTDR) (1991 to 24 July 2001). Bibliographies of studies and previous reviews were examined for references to other trials. Experts in the field were contacted.

Review update

We searched all reference lists of potential studies and previous reviews for relevant RCTs and contacted experts in the field. We searched the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) from 18 March 2011 to 31 August 2012 to identify ongoing studies (www.who.int/ictrp/en/). We searched the ICTRP for the protocols of the 16 new studies. Trial registries were not searched for the protocols of the original included studies because these were all published before 1998.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (Cathy Mathews, CM and Riabatu Abdullah, RA (original review); and Adel Ferreira, AF and Taryn Young, TY or CM or Moleen Zunza, MLZ (update)) independently screened titles and abstracts of the electronic search results. We obtained all the eligible abstracts of comparative studies in full‐text format, and two review authors (CM and RA original review and AF and TY or CM update) independently reviewed them for inclusion using prespecified eligibility criteria. We included all studies that reported random allocation. We assessed the risk of bias in the methods of sequence generation and allocation, as described in the section 'Assessment of risk of bias in included studies' and considered risk of bias interpreting the strength of evidence for each intervention.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (CM and Nicol Coetzee, NC or Merrick Zwarenstein, MZ (original review) and AF and TY or CM or MLZ (update)) independently abstracted study characteristics and outcomes including information on: social context (developing (World Bank classification: countries with low or middle levels of gross national product (GNP) per capita as well as five high‐income developing economies ‐ Hong Kong (China), Israel, Kuwait, Singapore and the United Arab Emirates. These five economies are classified as developing despite their high per‐capita income because of their economic structure or the official opinion of their governments. Several countries with transition economies are sometimes grouped with developing countries based on their low or middle levels of per‐capita income, and sometimes with developed countries based on their high industrialisation (World Bank 2012)) or developed country); access to health services; legislative context (permissive or proscriptive public health legislation); methodological quality of study; type of health facility; type of provider (for example, nurse, physician, DIS); participants; type of interventions; outcome measure; results and correspondence required using a data extraction form.

We resolved disagreements by discussion. We summarised data from included studies in the Characteristics of included studies table and data from excluded studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We summarised studies with insufficient information in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. Where there were missing data, we attempted to contact study authors by email.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (AF and CM or MLZ) independently evaluated the risk of bias using The Cochrane Collaboration's tool (Higgins 2011a). We made judgements about the presence of bias by selecting one of three categories of risk of bias: low risk, high risk and unclear risk of bias. We resolved disagreements by discussion. If we could not reach consensus, we involved a third independent review author (TY). We contacted trial authors if there were any unclear issues and, if we received no response, we made a judgement of 'unclear risk of bias'.

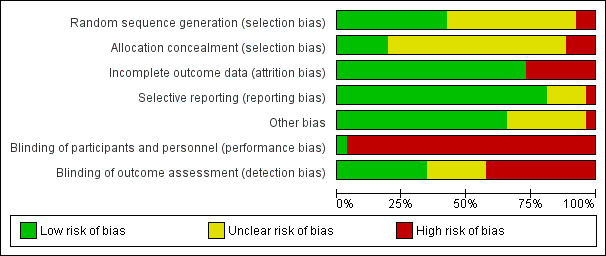

We assessed and summarised the following main items in the 'Risk of bias' table: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participant and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, whether incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed, selective reporting and any other bias. We searched the ICTRP for protocols of the 16 additional studies to assess selective reporting bias. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the 'Risk of bias' graphs, which illustrate the proportions of studies with low, high and unclear risk of bias. In the 10 studies of the original review, the ICTRP was not searched; instead, the methods and result sections were compared to evaluate if the same outcomes were reported in these two sections. If the protocol was not available, the methods and results sections were compared to assess selective reporting bias.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Measures of treatment effect

The review authors prepared tables summarising the results of each study for each comparison.

We defined re‐infection rate in index patients as the percentage of index patients with a repeated diagnosis of the same STI divided by the number of index patients retested.

Partners elicited, notified, presenting for care, tested, treated or harmed: we assumed that the number of units of each outcome per index patient was a random variable following a Poisson distribution. We assumed that the index patients from the groups within a study had similar distributions for exposure time to partners, for time to notify their partners, and that the same assumption held for partners with respect to the time taken to present to the health service. The value of the mean and the variance of a Poisson distribution are the same.

To calculate a CI for the difference in relevant outcomes, we used the normal approximation to the Poisson distribution since only summarised data from the included RCTs were available.

The approximate 95% CI for the rate difference is given by:

(Lamda1 ‐ Lamda2) ± 1.96√ (lamda1/n1 + lamda2/n2),

where lamda1 and lamda2 are the rates of partners per index patient in two groups, and n1 and n2 the number of index patients.

To calculate the standard error (SE) the formula used was:

(upper limit of 95% CI ‐ lower limit of 95% CI)/3.92.

To calculate the standard deviation (SD) the formula used was:

SE/√ (1/Nexp+ 1/Ncont),

where Nexp is the number of index patients randomised to the experimental group and Ncont is the number of index patients randomised to the control group

For continuous outcomes (number of partners elicited, notified, presenting for care, tested, treated or harmed), we recorded the mean (in number of partners per index patient randomised), SE and sample size. Where the exact numbers of partners were not available, we contacted study authors. If authors did not respond or could not provide the exact numbers, the mean difference (MD) could not be calculated and we reported the study findings descriptively. In studies where the rate of partners elicited per index patient was not reported, we used the number of contact cards given to the index patient as a proxy indicator.

We described the delay in partners presenting for care as the mean or median number of days after index patient enrolment.

Unit of analysis issues

We dealt with studies with multiple intervention groups as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Intervention Reviews (Higgins 2011b). We compared each intervention arm with another.

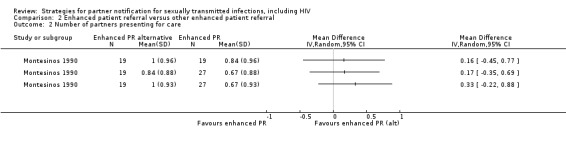

Where this resulted in shared intervention groups, we did not perform a meta‐analysis to prevent 'double‐counts' of participants. In these studies, we described the results in narrative form (Ellison undated; Montesinos 1990). We did not include any cluster randomised trials and, therefore, no adjustments were necessary.

Dealing with missing data

Where there were missing data, we attempted to obtain the data by contacting study authors by email. We contacted the authors of eight trials and authors provided requested data for five of the eight trials.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed sources of clinical and methodological heterogeneity by looking at characteristics of studies, evaluating similarity between type of participants, intervention used and outcomes. We calculated the Chi2 test for heterogeneity (Deeks 2011), and the I2 statistic to evaluate statistical heterogeneity. Values of the I2 statistic were interpreted as follows (Deeks 2011): 0% to 40%: might not be important; 30% to 60%: might represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: might represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: might represent considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not find a sufficient number of studies to produce funnel plots to investigate publication bias for specific comparisons.

Data synthesis

We analysed data according to paired partner referral strategies (Table 6). We organised the comparisons first according to the four main PN strategies (1. enhanced patient referral, 2. EPT, 3. contract referral, 4. provider referral). Each main strategy was compared with simple patient referral and then with each other, if trials were available. We compared each enhanced patient referral with another enhanced patient referral. This resulted in 10 comparisons (Table 6).

2. Summary of comparisons with data available and STI studied.

| Partner notification strategy, intervention | Partner notification comparator, comparison number (number of trials) | STI included in trials | ||||

| Simple patient referral | Enhanced patient referral | Expedited partner therapy | Contract referral | Other enhanced patient referral | ||

| Enhanced patient referral | 1 (16) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 2 (2) | Gonorrhoea, chlamydia, non‐gonococcal urethritis, trichomonas, pelvic inflammatory disease, STI syndromes |

| Expedited partner therapy | 3 (8) | 4 (5)* | ‐ | ‐ | Not applicable | Gonorrhoea, chlamydia, trichomonas, STI syndromes |

| Contract referral | 5 (5) | 6 (1) | 7 (1) | ‐ | Not applicable | Gonorrhoea, trichomonas, HIV |

| Provider referral | 8 (3)† | 9 (1) | No trials | 10 (2) | Not applicable | Non‐gonococcal urethritis, syphilis, HIV |

* Comparison includes one trial comparing combinations of expedited partner therapy and patient referral.

† Comparison Includes one trial comparing a choice between provider or simple patient referral and simple patient referral.

‐ Indicates combinations of an intervention and comparison that are covered elsewhere in the table; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; STI: sexually transmitted infection.

The largest group of trials (Table 6; comparison 1, enhanced patient referral versus simple patient referral) included several different interventions to enhance the outcomes of patient referral. We grouped these into six categories: (1) patient referral with DIS or health adviser, (2) postal testing kit, (3) information booklet, (4) disease‐specific website, (5) additional counselling or (6) showing a videotape.

We performed meta‐analyses where appropriate using random‐effects models to report the pooled MD (for continuous outcomes) or risk ratio (RR for dichotomous outcomes) with 95% CI. When there was a moderate or low level of heterogeneity (I2 ≤ 50%), we pooled results. If there was more substantial evidence of heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), we pooled the results of individual studies if appropriate or described in the narrative. We reported results of tests for heterogeneity (Tau2, Chi2 test with number of degrees of freedom (df), P value and I2 statistic).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We used subgroup analyses to explore possible sources of heterogeneity. These included: age of participant, gender, specific STIs investigated, setting (developed vs. developing country) and category of healthcare worker.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis on the primary outcome, re‐infection rate of index patient with curable STIs. Given the limited numbers of trials and meta‐analyses, the sensitivity analysis examined only the effect of attrition bias. We repeated meta‐analyses excluding trials with more than 20% attrition and compared results with the primary analysis.

'Summary of findings' table

We interpreted results using a 'Summary of findings' table, which provided key information about the quality of evidence for the studies included in a comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on the primary outcome. We imported data from Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2011), using the GRADE profiler (GRADE 2004). We selected the primary outcome of re‐infection in the index case for the 'Summary of findings' table.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

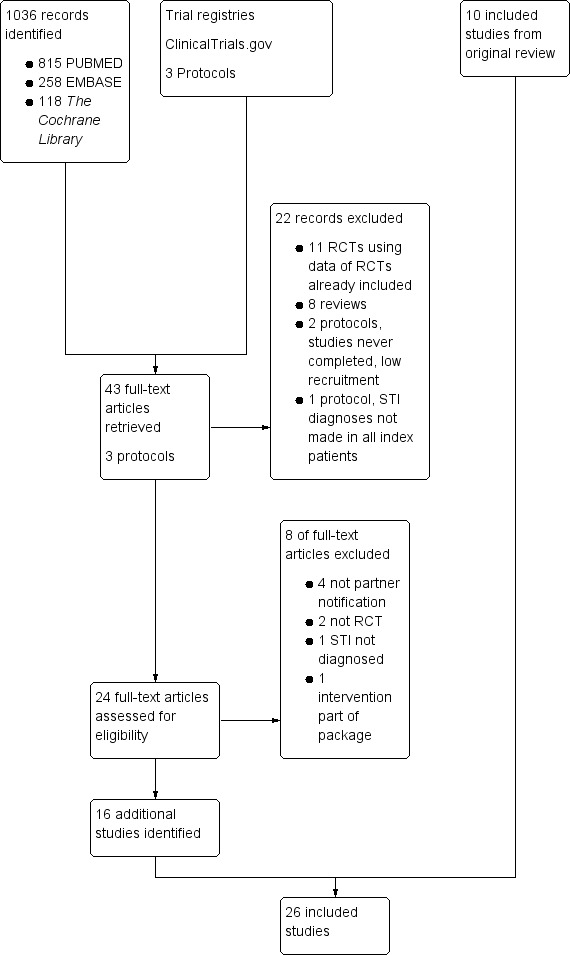

The initial search (1966 to 24 July 2001; Mathews 2001) identified 11 RCTs, including 8041 participants. The updated search (5 January 2001 to 31 August 2012) identified an additional 16 RCTs (9597 participants; 6841 women and 2756 men). One study was listed as awaiting classification (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). In the original review, Levy 1998 (with 60 participants) was listed as under 'Included studies' but, in this update, it was placed under 'Characteristics of studies awaiting classification' because no results were available. We found four ongoing studies in trial registers (Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Included studies

Twenty‐six RCTs (Figure 3) were included in the review including 17,578 participants (Characteristics of included studies). Most of the trials (14) were conducted in the US, four in the UK, two in Denmark, and one each in Australia, Malawi, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Most trials (21) were based in public health clinics. One was conducted in a large academic medical centre (Trent 2010), three in general practice (Andersen 1998; Low 2006b; Ostergaard 2003), and one on a university campus (Montesinos 1990).

3.

Flow diagram detailing the updated search and selection of studies.

Participants

Trials were conducted among patients with gonorrhoea (three trials, Cleveland undated; Potterat 1977; Solomon 1988); gonorrhoea or non‐gonococcal urethritis (one trial, Montesinos 1990); non‐gonococcal urethritis only (one trial, Katz 1988); chlamydia (six trials, Andersen 1998; Apoola 2009; Cameron 2009; Low 2006b; Ostergaard 2003; Schillinger 2003); syphilis (one trial, Peterman 1997); HIV (two trials, Brown 2011; Landis 1992); chlamydia or gonorrhoea, or both (four trials, Golden 2005; Kerani 2011; Kissinger 2005; Wilson 2009); trichomonas (two trials, Kissinger 2006; Schwebke 2010); PID (one trial, Trent 2010); and chlamydia or non‐gonococcal urethritis (one trial, Tomnay 2006). Four trials in developing countries where syndromic diagnoses are made included patients with any STI syndrome (Ellison undated; Faxelid 1996; Moyo 2002; Nuwaha 2001). In six studies, STI diagnoses were made clinically, based on symptoms or clinic tests (Ellison undated; Faxelid 1996; Katz 1988; Moyo 2002; Nuwaha 2001; Trent 2010). In the other 20 trials, STI diagnoses (other than non‐gonococcal urethritis) were confirmed with laboratory testing. There were no RCTs among patients with laboratory‐diagnosed hepatitis B, genital herpes or chancroid.

Six trials included male patients only, or reported over 90% male index patients (Cleveland undated; Katz 1988; Kerani 2011; Kissinger 2005; Potterat 1977; Solomon 1988). Seven trials included female index patients only (Andersen 1998; Apoola 2009; Cameron 2009; Kissinger 2006; Schillinger 2003; Schwebke 2010; Trent 2010).The remaining trials included male and female index patients. Two trials included men who had sex with men (Kerani 2011; Landis 1992) and one included male and female injecting‐drug users (Landis 1992).

Types of interventions

Included studies investigated the effects of various PN strategies (Table 6; Table 7):

3. Summary of included studies and outcomes reported by authors, according to partner notification strategies and comparisons.

|

Partner notification strategy Comparison number, comparison |

N (studies) |

n (participants) |

Outcomes, as reported in any included RCT | Study ID |

| ENHANCED PATIENT REFERRAL | ||||

| 1. Enhanced patient referral vs. simple patient referral | 16 | 7642 | Index patient returning for a test of cure Knowledge of the index patient Number of partners notified and referral of partners for treatment Proportion of index patients with at least 1 partner tested Proportion of index cases with at least 1 sexual partner treated Proportion of index patients with at least 1 partner positive for C. trachomatis Number of partners treated per index patient 6 weeks after randomisation Number of partners elicited Proportion of index cases with a positive chlamydia test result 6 weeks after randomisation Proportion of index cases with all sexual partners treated Acceptability of Internet for use in standard partner notification Partners located Index re‐infection Harms ‐ adverse effects of medication Index patient 72‐hour follow‐up Medication adherence Temporary abstinence from sexual intercourse as evidence of self care Behavioural change Partners contacted Partners tested Partners testing positive Time until testing of partners Number of partners treated per index case Number of partners identified per index Number of traceable partners Number of partners treated within 28 days Proportion of index patients with at least 1 partner treated within 28 days per index case |

Andersen 1998 Apoola 2009 Cleveland undated Cameron 2009 Ellison undated Kerani 2011 Katz 1988 Kissinger 2005 Kissinger 2006 Low 2005 Moyo 2002 Ostergaard 2003 Solomon 1988 Tomnay 2006 Trent 2010 Wilson 2009 |

| 2. Enhanced patient referral vs. other enhanced patient referral method | 2 | 1336 | Partners presenting for care Partners elicited Partners treated |

Montesinos 1990 Ellison undated |

| EXPEDITED PARTNER THERAPY | ||||

| 3. EPT vs. simple patient referral | 8 | 6537 | Re‐infection rate of index patient Number of partners notified Partner treatment Sexual outcomes such as having unprotected sex before partner took medication, re‐initiated sex with partner, unprotected sex with any partner Partners elicited Index patient 2‐week post‐treatment return Harms ‐ fighting and refusal of intercourse Side effects of drugs Partner testing |

Cameron 2009 Golden 2005 Kerani 2011 Kissinger 2005 Kissinger 2006 Nuwaha 2001 Schillinger 2002 Schwebke 2010 |

| 4.1 EPT vs. enhanced patient referral | 4 | 1253 | Re‐infection rate of index patient Number of partners notified Partner testing Partner treatment Sexual outcome (unprotected sex, re‐initiated sex with untreated partner) |

Cameron 2009 Kerani 2011 Kissinger 2005 Kissinger 2006 |

| 4.2 EPT and enhanced patient referral vs. simple patient referral | 1 | 41 | Number of partners notified Number of partners treated Method (telephone or in person) of partner notification used Partner tested for HIV/syphilis Adverse events |

Kerani 2011 |

| CONTRACT REFERRAL | ||||

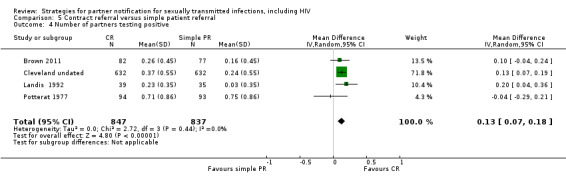

| 5 Contract referral vs. simple patient referral | 5 | 2006 | Number of partners notified Partners presenting to health service Partners testing positive |

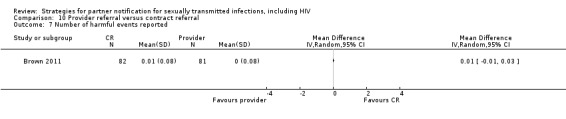

Brown 2011 Cleveland undated Landis 1992 Potterat 1977 Schwebke 2010 |

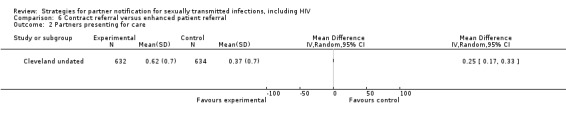

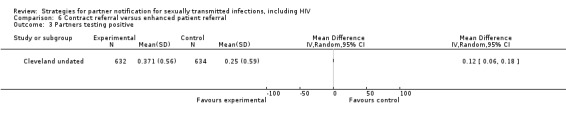

| 6. Contract referral vs. enhanced patient referral | 1 | 1266 | Partners presenting for care Partners testing positive |

Cleveland undated |

| 7. Contract referral vs. EPT | 1 | 324 | Re‐infection index patient | Schwebke 2010 |

| 8. PROVIDER REFERRAL | ||||

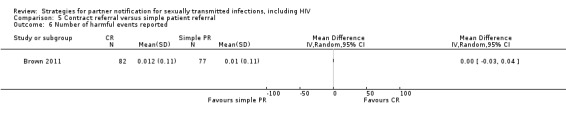

| 8.1 Provider referral vs. simple patient referral | 2 | 596 | Partners located Partners treated Partner visit to the clinic during the 30 days after index enrolment Harms Partners testing positive |

Brown 2011 Katz 1988 |

| 8.2 Choice between provider or simple patient referral vs. simple patient referral | 1 | 396 | Partners elicited Number of partners notified Partners treated Harms |

Faxelid 1996 |

| 9. Provider referral vs. enhanced patient referral | 1 | 461 | Partners elicited Partners testing positive Partners treated |

Katz 1988 |

| 10. Provider referral vs. contract referral | 2 | 2206 | Partners tested Partners treated Partner presenting for care Harms Partners testing positive |

Brown 2011 Peterman 1997 |

The outcomes listed are those reported by the authors of the RCTs. Not all were named primary or secondary outcomes in the review.

EPT: expedited partner therapy; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Enhanced patient referral versus simple patient referral;

Enhanced patient referral versus other enhanced patient referral method;

EPT versus simple patient referral;

EPT versus enhanced patient referral;

EPT and enhanced patient referral versus simple patient referral;

contract referral versus simple patient referral;

contract referral versus enhanced patient referral;

contract referral versus EPT;

provider referral versus simple patient referral;

choice between provider or simple patient referral versus simple patient referral;

provider referral versus enhanced patient referral;

provider referral versus contract referral.

Outcomes

Outcomes assessed are reported in Table 7. The comprehensive details of included studies can be seen in the Characteristics of included studies table.

One study from the original review was classified as a study awaiting assessment because there were no results available (Levy 1998) (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

Four ongoing studies were identified from the trial register (Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Excluded studies

We excluded 11 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies for details).

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias for each study is presented in the 'Risk of bias' table in the section Characteristics of included studies. Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the summary of risk of bias in all the studies.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Eleven trials reported adequate generation of the random allocation sequence (Apoola 2009; Brown 2011; Cameron 2009; Faxelid 1996; Kissinger 2005; Kissinger 2006; Low 2006b; Nuwaha 2001; Tomnay 2006; Trent 2010; Wilson 2009). Of these trials, eight used blocked randomisation (Apoola 2009; Brown 2011; Cameron 2009; Kissinger 2005; Kissinger 2006; Low 2006b; Tomnay 2006; Wilson 2009), two trials used computer‐generated random numbers tables (Nuwaha 2001; Trent 2010), and, in one study, lots were drawn by index patient (Faxelid 1996). Sequence generation was adequate in six of nine trials reporting the primary outcome of re‐infection with a bacterial STI (Cameron 2009; Kissinger 2005; Kissinger 2006; Low 2006b; Tomnay 2006;Wilson 2009).

In 13 trials, random sequence generation was unclear (Cleveland undated; Ellison undated; Golden 2005; Katz 1988; Kerani 2011; Landis 1992; Montesinos 1990; Moyo 2002; Ostergaard 2003; Peterman 1997; Schillinger 2003; Schwebke 2010; Solomon 1988) and two trials reported methods used that can introduce a high risk of bias (Andersen 1998; Potterat 1977). In Andersen 1998, the date of birth of index patient was used and, in Potterat 1977, assignment of index patient was performed alternately to specific intervention arms. Both of these trials reported secondary outcomes only.

Allocation concealment

Five trials reported adequate allocation concealment (Apoola 2009; Brown 2011; Low 2006b; Schillinger 2003; Tomnay 2006). Of these, four trials reported the use of sealed, opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes (Apoola 2009; Brown 2011; Schillinger 2003; Tomnay 2006), and one trial reported the use of a centralised telephone service (Low 2006b). In 18 trials, the methods used for allocation concealment were not adequately described (Andersen 1998; Cameron 2009; Cleveland undated; Faxelid 1996; Golden 2005; Katz 1988; Kerani 2011; Kissinger 2005; Kissinger 2006; Landis 1992; Moyo 2002; Nuwaha 2001; Ostergaard 2003; Potterat 1977; Schwebke 2010; Solomon 1988; Trent 2010; Wilson 2009). Allocation concealment was adequate in three of nine trials reporting the primary outcome of re‐infection with a bacterial STI.

Three studies reported methods that could introduce a high risk of bias (Ellison undated; Montesinos 1990; Peterman 1997). In Ellison et al., the interventions were allocated in turn to each consecutive patient according to a printed schedule, which could have influenced enrolment or exclusion and hence the intervention received by the index patients (Ellison undated). In Montesinos et al., the protocol used in the intervention was colour coded and the counsellor removed the protocol for the next index patient from a randomly ordered set (Montesinos 1990). Peterman et al. reported that the assignment was known to the interviewer before contact with index patients and sequentially adapted (Peterman 1997).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

Twenty‐five trials did not have blinding of the participants or the personnel (Andersen 1998; Apoola 2009; Brown 2011; Cameron 2009; Cleveland undated; Ellison undated; Faxelid 1996; Golden 2005; Katz 1988; Kerani 2011; Kissinger 2005; Kissinger 2006; Landis 1992; Low 2006b; Montesinos 1990; Moyo 2002; Nuwaha 2001; Peterman 1997; Potterat 1977; Schillinger 2003; Schwebke 2010; Solomon 1988; Tomnay 2006; Trent 2010; Wilson 2009). In one trial, the index patient received identical specimen collection kits to be given to their partners, and was, therefore, blinded to the intervention in which they were taking part (Ostergaard 2003).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

Eleven trials did not report blinding of the outcome assessors (Apoola 2009; Faxelid 1996; Katz 1988; Kerani 2011; Kissinger 2005; Kissinger 2006; Montesinos 1990; Moyo 2002; Nuwaha 2001; Peterman 1997; Potterat 1977). In five trials, the outcome assessors were blinded (Cleveland undated; Ellison undated; Low 2006b; Solomon 1988; Wilson 2009). Cameron et al. reported that the laboratory personnel (primary outcome) were blinded but not the interviewers (Cameron 2009). We judged the risk of bias as low. In six studies, the blinding of outcome assessors was unclear (Andersen 1998; Landis 1992; Ostergaard 2003; Schwebke 2010; Tomnay 2006; Trent 2010). In the remaining three studies, the outcome assessor was not blinded but we judged the risk of bias as low because the primary outcome was objectively assessed (Brown 2011; Golden 2005; Schillinger 2003).

Incomplete outcome data

Seven trials had a high (> 20%) attrition rate (Cameron 2009; Golden 2005; Kerani 2011; Kissinger 2005; Moyo 2002; Schwebke 2010; Trent 2010), including four of nine trials reporting re‐infection with a bacterial STI as an outcome. In Cameron 2009, 65% of index patients submitted at least one urine sample in 12 months, while in Golden 2005, 68% of index patients completed the study. In Kerani 2011, 71% of index patients completed baseline and follow‐up interviews. In Kissinger 2005, 79% of index patients had a follow‐up interview but only 37.5% were retested, and in Moyo 2002, only 50% of index patients had a follow‐up interview. In Schwebke 2010, 40% of index patients completed the study. In Trent 2010, 62% of index patients had a follow‐up interview.

Selective reporting

We compared the trial protocols with published trial results sections to assess reporting bias. If the trial protocol was not available, we compared the methods and results sections of the trial. We searched three trial registries for the protocols of the 16 additional studies included in this update. Protocols were available for five of these studies (Apoola 2009; Kissinger 2006; Low 2006b; Schwebke 2010; Wilson 2009).

We judged 21 trials to have a low risk of reporting bias either because the primary outcome stated in the protocol was reported in the trial result sections (Apoola 2009; Schwebke 2010), or the outcomes stated in the method sections were reported in the result sections (Andersen 1998; Brown 2011; Cameron 2009; Cleveland undated; Ellison undated; Faxelid 1996; Katz 1988; Kerani 2011; Landis 1992; Montesinos 1990; Moyo 2002; Nuwaha 2001; Ostergaard 2003; Peterman 1997; Potterat 1977; Schillinger 2003; Schwebke 2010; Solomon 1988; Tomnay 2006; Trent 2010).

We considered four trials to have an unclear risk of reporting bias because the outcomes reported in the results sections differed from those stated in the method sections (Golden 2005; Kissinger 2005), or protocols (Kissinger 2006; Low 2006b). In Kissinger 2006, the protocol had primary and secondary outcomes whereas in the trial report outcomes were not divided into primary and secondary. Furthermore, additional sexual and behavioural outcomes were reported. Low et al. reported some outcomes in the published paper that differed from the protocol (Low 2006b).

We assessed one trial as being at high risk of reporting bias. In Wilson 2009, the primary outcomes stated in the protocol differed from those stated in trial report; in the protocol there were also three intervention arms described but only two were reported in the trial publication.

Other potential sources of bias

One study had a high potential for other bias (Peterman 1997). The authors of the study reported contamination between the three groups caused by overlap of partners common to index patients. In eight studies, it was unclear if there was any other potential source of bias (Andersen 1998; Cleveland undated; Golden 2005; Kerani 2011; Landis 1992; Nuwaha 2001; Potterat 1977; Solomon 1988). Of these seven studies, in five no comparisons of baseline characteristics between study arms were given (Andersen 1998; Cleveland undated; Landis 1992; Potterat 1977; Solomon 1988). In Golden 2005, selective reporting of subgroups might have introduced bias and in Nuwaha 2001, partners of the patient referral group could have been treated elsewhere leading to misclassification bias. In the remainder of the studies, the risk for potential sources of bias was low.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Enhanced patient referral

1. Enhanced patient referral versus simple patient referral

Sixteen studies looked at different types of enhanced patient referral compared with simple patient referral among patients with gonorrhoea (Cleveland undated; Solomon 1988), chlamydia (Andersen 1998; Apoola 2009; Cameron 2009; Low 2006b; Ostergaard 2003), non‐gonococcal urethritis (Katz 1988), gonorrhoea or chlamydia (Kerani 2011; Kissinger 2005; Wilson 2009), trichomoniasis (Kissinger 2006), chlamydia or non‐gonococcal urethritis (Tomnay 2006), PID (Trent 2010), or any STI syndrome (Ellison undated; Moyo 2002).

There were seven different types of enhanced patient referral interventions for patients or partners: 1) an additional counselling session (Cleveland undated; Ellison undated; Moyo 2002; Wilson 2009); 2) a home testing kit for the partners to use and send back to a laboratory (Andersen 1998; Cameron 2009; Ostergaard 2003), or for the partners to bring back to the clinic (Apoola 2009); 3) an additional information booklet to be given to the partner (Kissinger 2005; Kissinger 2006); 4) a videotape shown to the index patient (Solomon 1988; Trent 2010); 5) a disease‐specific website was available to the partner (Kerani 2011; Tomnay 2006); 6) health education messages for the index case (Ellison undated); and 7) health education plus counselling for the index patient (Ellison undated). In addition, two studies compared patient referral performed by a contact tracer (DIS or health adviser) with patient referral performed by a nurse (Katz 1988; Low 2006b).

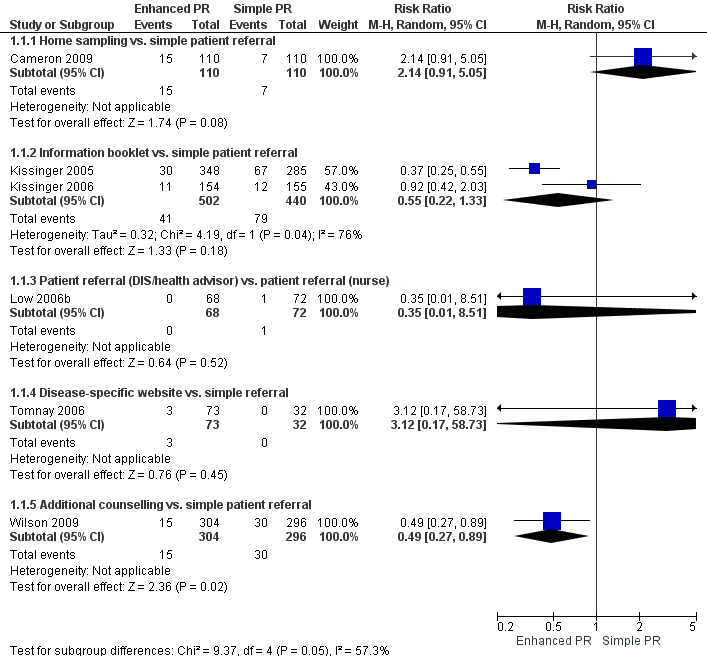

Primary outcome

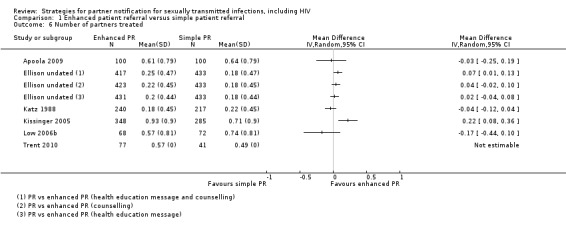

Six studies (2007 participants) assessed the index patient re‐infection rate (Cameron 2009; Kissinger 2005; Kissinger 2006; Low 2006b; Tomnay 2006; Wilson 2009) (Figure 4). Owing to substantial heterogeneity (Tau2 = 0.38; Chi2 = 16.86, df = 5 (P value = 0.005); I2 = 70%), the results of individual studies were not pooled. In one comparison, the risk of re‐infection in the index patients was 51% lower in the enhanced patient referral (additional counselling) compared with the simple patient referral group (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.89) (Wilson 2009). In two smaller studies, the risk of re‐infection was higher in index patients receiving the enhanced patient referral strategy but CIs included the possibility of no difference (Cameron 2009; Tomnay 2006). In the other three studies, there was no statistical evidence of a difference between enhanced and simple patient referral (Table 8).

4.

Forest plot: 1 Enhanced patient referral versus simple patient referral, outcome: 1.1 Re‐infection in index patient, by STI.

4. Enhanced patient referral versus simple patient referral, re‐infection in the index patient, effect size.

| Comparison |

N (studies) |

n (participants) |

Study ID |

RR (95% CI) |

Test for heterogeneity I2; Chi2, P value |

| Home sampling kit vs. simple patient referral | 1 | 220 | Cameron 2009 | 2.14 (0.91 to 5.05) | n/a |

| Information booklet vs. simple patient referral | 2 | 942 | Kissinger 2005; Kissinger 2006 | 0.55 (0.22 to 1.33) | 76%; 4.19, P value = 0.04 |

| Patient referral (DIS/health adviser) vs. patient referral (nurse) | 1 | 140 | Low 2005 | 0.35 (0.01 to 8.51) | n/a |

| Disease‐specific website vs. simple patient referral | 1 | 105 | Tomnay 2006 | 3.12 (0.17 to 58.73) | n/a |

| Additional counselling vs. simple patient referral | 1 | 600 | Wilson 2009 | 0.49 (0.27 to 0.89) | n/a |

Enhanced patient referral is taken as the experimental group. Risk ratio (RR) < 1 indicates a lower re‐infection risk after enhanced patient referral than simple patient referral. If RR = 1, the risk of re‐infection is the same in both groups. If RR > 1, there is a higher risk of re‐infection in the enhanced patient referral group. In the trial by Low et al., the outcome was assessed in a minority of index patients.

CI: confidence interval; DIS: disease intervention specialist; n/a: not applicable; RR: risk ratio.

We judged the quality of evidence for the primary outcome, using the GRADE approach, as low for four of the five enhanced patient referral interventions. We judged additional counselling to provide moderate evidence of a beneficial effect when compared with simple patient referral but there was only one trial in this group (Wilson 2009) (Table 1).

Secondary outcomes

Twelve studies (6045 participants) used five different comparisons and assessed the number of partners elicited (Andersen 1998; Apoola 2009; Cameron 2009; Cleveland undated; Ellison undated; Katz 1988; Kerani 2011; Kissinger 2005; Low 2006b; Moyo 2002; Solomon 1988; Tomnay 2006). There was no evidence of clinically relevant differences between enhanced and simple patient referral strategies (Table 9). When simple patient referral delivered by a nurse was compared with specialist contact tracer (DIS or health adviser) (Katz 1988; Low 2006b), the number of partners elicited was slightly higher in the simple patient referral (nurse) group. We conducted a sensitivity analysis, removing the trial by Andersen 1998 (high risk of bias in random sequence generation), but there was no appreciable difference in the results.

5. Enhanced patient referral versus simple patient referral, number of partners elicited per index patient randomised, effect size.

| Comparison |

N (studies) |

n (participants) |

Study ID |

MD (95% CI) |

Test for heterogeneity I2; Chi2, P value |

| Home sampling kit vs. simple patient referral | 3 | 516 | Cameron 2009; Andersen 1998; Apoola 2009 | 0.00 (‐0.19 to 0.19) | 0%; 0.32, P value = 0.85 |

| Additional counselling vs. simple patient referral | 3 | 2401 | Cleveland undated; Ellison undated; Moyo 2002 | 0.1 (0.00 to 0.19) | 0%; 1.17, P value = 0.56 |

| Patient referral (DIS) vs. patient referral (nurse) | 2 | 597 | Katz 1988; Low 2005 | ‐0.40 (‐0.57 to ‐0.24) | 0%; 0.03, P value = 0.87 |

| Information booklet vs. simple patient referral | 1 | 633 | Kissinger 2005 | 0.0 (‐0.22 to 0.22) | n/a |

| Disease‐specific website vs. simple patient referral | 2 | 140 | Kerani 2011; Tomnay 2006 | ‐0.15 (‐0.72 to 0.42) | 13%; 1.15, P value = 0.28 |

Enhanced patient referral is taken as the experimental group. Mean difference (MD) < 0 indicates that simple patient referral resulted in more partners elicited; MD = 0 indicates no difference between groups; MD > 0 indicates more partners elicited in the enhanced patient referral group.

CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; n/a indicates not applicable.

In Ellison et al. there were four intervention arms comparing three different enhanced patient referral methods with simple patient referral: (1) patient referral with a health education message, (2) patient referral with counselling and (3) patient referral with health education message and counselling (Ellison undated). Small increases in the number or partners elicited per index patient were observed in the enhanced patient referral strategy with a health education message (MD 0.25, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.39) and health education message plus counselling (MD 0.6, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.76). In Solomon et al. the authors reported that there was no evidence of differences between enhanced patient referral (videotape) and simple patient referral group for number of partners elicited (Solomon 1988).

Six studies (1885 participants) assessed number of partners notified (Cameron 2009; Moyo 2002; Ostergaard 2003; Tomnay 2006; Trent 2010; Wilson 2009). In Trent 2010 and Wilson 2009, the exact number of partners notified was not reported so we could not calculate the MD. In three studies (Table 10), there was no evidence of a difference in the number of partners notified per index patient between the groups (Cameron 2009; Ostergaard 2003; Tomnay 2006). In Moyo et al. additional counselling resulted in slightly more partners being notified (Moyo 2002).

6. Enhanced patient referral versus simple patient referral, number of partners notified per index patient randomised, effect size.

| Comparison |

N (studies) |

n (participants) |

Study ID |

MD (95% CI) |

Test for heterogeneity I2; Chi2, P value |

| Home sampling kit vs. simple patient referral | 2 | 782 | Cameron 2009; Ostergaard 2003 | 0.01 (‐0.12 to 0.14) | 0%; 0.01, P value = 0.93 |

| Additional counselling vs. simple patient referral | 2 | 272 | Moyo 2002; Wilson 2009 |

0.21 (0.05 to 0.36) data not available |

n/a |

| Disease‐specific website vs. simple patient referral | 1 | 105 | Tomnay 2006 | ‐0.17 (‐0.68 to 0.35) | n/a |

| Videotape vs. simple patient referral | 1 | 77 | Trent 2010 | data not available | n/a |

Enhanced patient referral group is taken as the experimental group. Mean difference (MD) < 0 indicates that simple patient referral resulted in more partners notified; MD = 0 indicates no difference between groups; MD > 0 indicates more partners notified in the enhanced patient referral group.

CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; n/a indicates not applicable.

Five studies (2684 participants) assessed the number of partners who presented for care (Andersen 1998; Apoola 2009; Cameron 2009; Cleveland undated; Solomon 1988). Data were only available for four studies (Andersen 1998; Apoola 2009; Cameron 2009; Cleveland undated). There was no evidence that one group resulted in more partners who presented for care compared with another (MD 0.1, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.28; heterogeneity: Tau2 = 0.02; Chi2 = 12.59, df = 3 (P value = 0.006); I2 = 76%). In Solomon 1988), the authors reported no difference in number of partners presenting for care when a videotape was used.