Abstract

Most children who present with acute onset of barky cough, stridor, and chest-wall indrawing have croup. A careful history and physical examination is the best method to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out potentially serious alternative disorders such as bacterial tracheitis and other rare causes of upper-airway obstruction. Epinephrine delivered via a nebuliser is effective for temporary relief of symptoms of airway obstruction. Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment, and benefit is seen in children with all levels of severity of croup, including mild cases.

Croup is a common childhood disease characterised by sudden onset of a distinctive barky cough that is usually accompanied by stridor, hoarse voice, and respiratory distress resulting from upper-airway obstruction. Although most children with croup are deemed to have a mild and short-lived illness, the distress and disruption that families undergo is well known. Perhaps this upset is because of the nature of croup: the presentation is so unusual and frightening and predominantly affects young children, with symptoms that are usually worse during the early hours of the morning. Historically, before the advent of treatment with corticosteroids and racemic epinephrine for severe croup, intubation, tracheotomy, and death were typical outcomes. Treatment has evolved from barbaric methods including bleeding and application of leeches, through mist kettles (pot of boiling water), mist rooms, and mist tents, to the current evidence-based practice of corticosteroids and epinephrine delivered via nebuliser.1

Many unanswered questions linger. Why are croup symptoms worse at night? What predisposes some children to severe croup and others to a mild barky cough? What accounts for the stubbornly predictable biannual peak in the occurrence of croup? Is the cause of croup evolving as new viral triggers are identified? Is bacterial tracheitis a new emerging complication of croup? In this Seminar, we summarise the most current published work about the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of this important childhood disease and propose future research pathways for exploration.

Epidemiology, clinical course, and pathophysiology

Croup is one of the most frequent causes of acute respiratory distress in young children. The disease mainly affects those aged between 6 months and 3 years old, with a peak annual incidence in the second year of life of nearly 5%.2 However, croup does occur in babies as young as 3 months old and in adolescents.2 Although rare, adults can also develop croup symptoms.3 Boys are more susceptible than girls to the disorder, with an overall male/female preponderance of 1·4/1.2 In North America, croup season peaks in late autumn (September to December), but cases are recognised throughout the year, even during the summer.2 In odd-numbered years, the number of children admitted with croup during the peak season is about 50% more than during even-numbered years,4 which closely correlates with the prevalence of parainfluenza virus infection in the community (North America).

Symptom onset is typically abrupt and most usually happens at night, heralded by the appearance of a very characteristic and distinctive barky cough. Stridor, hoarse voice, and respiratory distress are seen frequently, as a result of upper-airway obstruction. These symptoms are frequently preceded by non-specific upper-respiratory-tract symptoms for 12–48 h before development of the barky cough and difficulty breathing. Croup symptoms are generally short-lived, with about 60% of children showing resolution of their barky cough within 48 h.5 However, a few children continue to have symptoms for up to 1 week.5

Croup symptoms nearly always become worse during night-time hours, and in our experience they fluctuate in severity depending on whether the child is agitated or calm.5 We do not know why croup symptoms tend to worsen at night, but a physiologically plausible explanation might lie with the known circadian fluctuations in endogenous serum cortisol, concentrations of which peak at about 0800 h and reach a trough between 2300 h and 0400 h.6, 7 In asthma, another frequent respiratory disease in which night-time symptoms generally prevail, postulated mechanisms include detrimental effects of nocturnal airway cooling, gastro-oesophageal reflux, and increased tissue inflammation in addition to the effect of endogenous plasma cortisol and epinephrine cycling.8 Perhaps similar physiological factors are at play in croup.

The symptoms of croup result from upper-airway obstruction caused by an acute viral infection, most typically parainfluenza types 1 and 3.4 Other viruses implicated in the disorder include influenza A, influenza B, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and metapneumovirus.2, 9 In published work, a strong association has been described between both human metapneumovirus and coronavirus HCoV-NL63 infection and croup in children.10, 11 Whether or not new pathogens are emerging is unknown. However, a likely possibility is that the increasing number of viruses seen in association with croup is merely a reflection of improvements in methods of detection. Work is ongoing to develop an effective vaccine against parainfluenza virus.12, 13

Laryngeal diphtheria is a well-known historical cause of croup, the occurrence of which is now very rare in immunised populations. However, outbreaks of diphtheric croup have been reported in case series from Russia14, 15, 16 and India.17 Measles remains an important cause of croup in non-immunised children. Treatment with vitamin A has been assessed and reported to be effective for prevention of secondary infections, especially croup, in children with severe measles.18, 19 The rarity of croup associated with measles and diphtheria in immunised children suggests that substantial progress could be made in the developing world with continued aggressive immunisation programmes against these pathogens.

Infection with a recognised pathogen leads to generalised airway inflammation and oedema of the upper-airway mucosa, including the larynx, trachea, and bronchi, then epithelial necrosis and shedding.20 Parainfluenza virus also activates chloride secretion and inhibits sodium absorption across the tracheal epithelium, contributing to airway oedema.21 The subglottic region becomes narrowed and results in the barky cough, turbulent airflow and stridor, and chest-wall indrawing. Further narrowing can lead to asynchronous chest-wall and abdominal movement, fatigue, and eventually to hypoxia, hypercapnia, and respiratory failure.22, 23

Why do some children develop severe symptoms or recurrent episodes of croup whereas others show only mild symptoms or can even be asymptomatic when faced with the same infection? Perhaps individual anatomy plays a part, since some children might have an intrinsically narrower subglottic space. Individual immune factors could be important too, with a range of severity of inflammatory response to infection. The peak incidence of croup at the age of 2 years is also somewhat unexplained and could be attributable to increased exposure to viral pathogens combined with the toddler's smaller subglottic space, leaving them at greater risk for airway narrowing. Current published work on these topics does not mention these questions.

Although the major concern for both clinicians and parents is the potential for severe respiratory distress, morbidity, and mortality,24 most children have mild short-lived symptoms.5 Of all children presenting to 24 general emergency departments in the province of Alberta, Canada, about 85% were classified as having mild croup and fewer than 1% as having severe croup (unpublished data). Even though most children have fairly mild symptoms, the sudden onset of croup symptoms during the night causes many parents to bring their child to an emergency department.24, 25 Consistent with these findings, fewer than 5% of children with croup are admitted to hospital in population-based studies.25, 26, 27 Of those with croup who are admitted, 1–3% are intubated.28, 29, 30, 31 Mortality seems to be very rare. By extrapolation of data from several sources,28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 we estimate a mortality rate of about 1 in 30 000 cases.

Differential diagnosis

In a child presenting with classic signs and symptoms of croup, alternate diagnoses are uncommon (panel ). However, clinicians must remain vigilant because other serious diseases can present with stridor and respiratory distress.

Panel. Differential diagnosis of croup.

-

•

Epiglottitis

-

•

Bacterial tracheitis

-

•

Foreign-body aspiration

-

•Tracheal

-

•Oesophageal

-

•

-

•

Retropharyngeal abscess

-

•

Peritonsillar abscess

-

•

Angioneurotic oedema

-

•

Allergic reaction

-

•

Laryngeal diphtheria

Bacterial tracheitis is a serious, life-threatening bacterial infection that can arise after an acute, viral respiratory-tract infection.34, 35, 36, 37 The child usually has a mild-to-moderate illness for 2–7 days but then becomes acutely worse.20 If they are febrile, have a toxic appearance (ie, look unwell and have reduced interaction with their environment), and do not respond favourably to treatment with nebulised epinephrine, bacterial tracheitis should be considered.34, 35, 37, 38 Treatment includes close monitoring of the airway and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, because intubation and respiratory support might be needed during the early stages of treatment when thick tracheal secretions can occlude the airway. The most frequently isolated pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus, but others include group A streptococcus, Moraxella catarrhalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae.20, 35, 37, 39, 40 Anaerobic bacteria have also been cultured from tracheal secretions of children with tracheitis.41

A second potentially life-threatening alternate diagnosis is epiglottitis. This disease is now seen rarely owing to widespread immunisation against H influenzae B.42, 43, 44 The sudden onset of high fever, drooling, dysphagia, anxiety, and a preference to sit upright and in the so-called sniffing position (ie, sitting forward with their head extended) to open the airway should prompt consideration of epiglottitis, as should a cough that does not have the characteristic barking sound of croup.20 In the case of possible epiglottitis or bacterial tracheitis, the most important aspect of treatment is maintenance of a secure airway by a doctor highly skilled in airway management.

Other very rare causes of stridor that should be considered in children presenting with atypical croup symptoms include foreign-body aspiration in the upper airway or oesophagus, peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscess, angio-oedema, and laryngeal diphtheria.45 In the case of foreign-body aspiration, onset is usually sudden with no prodrome or fever (unless secondary infection occurs). Hoarseness and barking cough are usually absent. Dysphagia could be present and stridor is noted variably. Children who have stridor secondary to the presence of a foreign body usually present with a clear history of ingestion.20 Peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscess could present with dysphagia, drooling, stridor, dyspnoea, tachypnoea, neck stiffness, and unilateral cervical adenopathy, and a lateral neck radiograph can show posterior pharyngeal oedema and retroflexed cervical vertebrae.46 Acute angioneurotic oedema or allergic reaction can present at any age and with rapid onset of dysphagia and stridor and possible cutaneous allergic signs such as urticarial rash. Children might have a history of allergy or previous attack.20 Laryngeal diphtheria has arisen historically in people of all ages, and a record of inadequate immunisation can be seen. Usually, a prodrome of pharyngitis symptoms is noted and onset is gradual over 2–3 days. Low-grade fever is present, hoarseness and barking cough occur along with dysphagia and inspiratory stridor, and the characteristic membranous pharyngitis is seen on physical examination.20

Diagnosis and ancillary testing

Croup is a clinical diagnosis. Key features include acute onset of a seal-like barky cough, stridor, hoarseness, and respiratory distress.20 Children might have fever, occasionally reaching a temperature as high as 40°C;47 however, they should not drool nor appear toxic. Laboratory tests are not needed to confirm the diagnosis in a child presenting with the typical clinical features of croup, but if tests are judged necessary they should be deferred if the child is in respiratory distress.48 Notably, rapid antigen tests and viral cultures do not aid in the routine acute management of a child with croup.48

Similarly, radiological studies are not recommended in a child who has a typical history of croup and who responds appropriately to treatment.48 Radiographs are not indicated if there is a clinical picture of epiglottitis or bacterial tracheitis. In children in whom the diagnosis is uncertain, however, an anteroposterior and lateral soft-tissue neck radiograph can be helpful in supporting an alternative diagnosis.49 If radiographs are obtained, however, epiglottitis is suggested by a thickened epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds.49, 50 A retropharyngeal abscess is indicated by bulging soft tissue of the posterior pharynx.50 Bacterial tracheitis can manifest as a ragged tracheal contour or a membrane spanning the trachea.34, 35, 50, 51, 52 However, radiographs can also be completely normal in children with these diagnoses.53 If radiographs are justified by an atypical clinical picture, the child must be closely monitored during imaging by skilled personnel with appropriate airway management equipment, because airway obstruction can worsen rapidly.

Cardiorespiratory monitoring, including continuous pulse oximetry, is indicated in children with severe croup but it is not necessary in mild cases.48 Also, children without severe croup could occasionally have low oxygen saturation, presumably as a result of intrapulmonary involvement of their viral infection; thus, ongoing assessment of overall clinical status is important.54, 55, 56

Assessment of severity

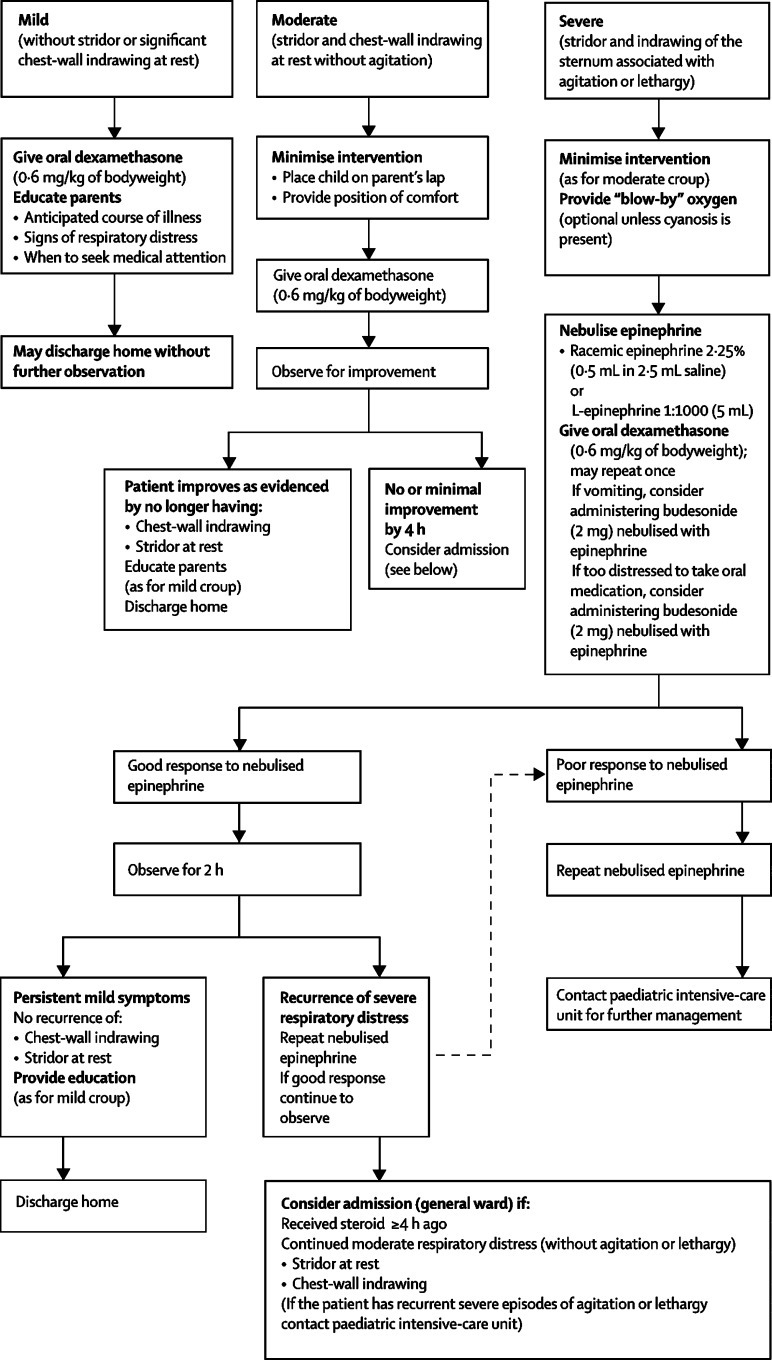

Determination of disease severity relies on clinical assessment. Various proposed methods for objective assessment of respiratory distress in children with croup are either impractical or insensitive to change across the full range of disease severity.23, 57, 58, 59 Consequently, in clinical trials of treatment effectiveness, outcome measures have mainly included clinical scores and health-care use.60, 61 Although such scores are useful for research studies, none has been shown to enhance routine clinical care, at least in part, because they are not reliable when used by a wide range of clinicians.62 Features useful in routine clinical assessment of children with croup as outlined in the figure .

Figure.

Algorithm for management of croup in the outpatient setting

Reprinted from reference 48 with permission.

General care

General consensus is that children with croup should be made as comfortable as possible, and clinicians should take special care during assessment and treatment not to frighten or upset them because agitation causes substantial worsening of symptoms.48 Sitting the child comfortably in the lap of a parent or caregiver is usually the best way to lessen agitation.48

Although we could not find any published evidence that oxygen should be administered to children who are showing signs of respiratory distress, widespread consensus indicates that oxygen treatment is beneficial in this circumstance.48, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 Oxygen can generally be administered without causing the child to be agitated via a plastic hose with the opening held within a few centimetres of the nose and mouth (referred to as blow-by oxygen).48

Humidified air

Treatment of croup with humidified air is not effective, despite its long history of use. Humidification of air is neither completely benign nor does it improve respiratory distress.48, 63, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 A systematic review of findings of three randomised controlled trials of humidified air treatment in emergency settings in a total of 135 children with mild-to-moderate croup concluded that there was no difference in croup score after such treatment.74 This systematic review did not include a later randomised controlled trial of 140 children with moderate-to-severe croup in a paediatric emergency department who were randomised to three arms: traditional standard humidified blow-by oxygen; 40% humidified oxygen; or 100% humidified oxygen, with a particle size generated to target the larynx.70 Measurement of humidified blow-by oxygen showed that this technique did not raise humidity above that of ambient room air, thus effectively serving as a placebo arm. The findings showed no difference in croup score, treatment with epinephrine or dexamethasone, or admission to hospital or additional medical care between the three groups.70

Apart from the lack of noted benefit, several potential difficulties with administration of humidified air have been identified. Hot humidified air can cause scald injuries;75 mist tents can disperse fungus and moulds into the environment unless they are properly cleaned;68 and most importantly, mist tents are cold and wet and separate the child from the parent, which usually causes them to be agitated and worsens their symptoms.73

Heliox

Helium is an inert low-density gas with no inherent pharmacological or biological effects. Administration of helium-oxygen mixture (heliox) to children with severe respiratory distress can reduce their degree of distress since the lower density helium gas (vs nitrogen) decreases airflow turbulence through a narrow airway. Heliox was compared with racemic epinephrine in a prospective randomised controlled trial of 29 children with moderate-to-severe croup who had received treatment with humidified oxygen and intramuscular dexamethasone.76 Clinical outcomes included a clinical croup score, oxygen saturation, and heart and respiratory rates. Both heliox and racemic epinephrine were associated with similar improvements in croup score over time.76 Findings of a second prospective, randomised, double-blind controlled trial in 15 children with mild croup presenting to an emergency department indicated a trend towards greater improvement in a clinical croup score in the heliox group versus the oxygen-enriched air group, although the scores did not differ significantly.77

However, since heliox has yet to be shown to offer greater improvements than standard treatments and can be difficult to use in unskilled hands, there is insufficient reason to recommend its general use in children with severe croup.76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83 Furthermore, there are practical limitations to heliox use, including limited fractional concentration of inspired oxygen in a child with significant hypoxia.

Pharmacotherapy

In this next section, we will review the use of two conventional treatments, corticosteroids and epinephrine, and several other categories of drugs, such as antipyretics, analgesics, antibiotics, β agonists, and decongestants. The rationale for review of this latter group of drugs is that, although these treatments are not recommended, they are sometimes used in children with croup.84

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids have a long history of use in children with croup; evidence for their effectiveness for treatment of croup is now clear (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 ). Children with severe croup and impending respiratory failure who are treated with corticosteroids have about a fivefold reduction in the rate of intubation;86 if they are intubated, they remain ventilated for about a third less time and have a sevenfold lower risk for reintubation than patients not treated with these drugs.89 In moderate-to-severe croup patients who are treated with corticosteroids, an average 12-h reduction in the length of stay in the emergency department or hospital, a 10% reduction in the absolute proportion treated with nebulised epinephrine, and a 50% reduction for both the number of return visits and admissions for treatment.60

Table 1.

Meta-analyses of the effectiveness of corticosteroid treatment versus placebo in croup

| Studies (n) | Patients (n) | Treatment | Outcomes | Results* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Griffin (2000)85 | 8 | 574 | Nebulised corticosteroid | Primary: change in clinical croup score 5 h after treatment | Improvement (RR 1·48 [1·27–1·74]) |

| Secondary: admission | Reduction (RR 0·56 [0·42–0·75]) | ||||

| Kairys (1989)86 | 10 | 1286 | Oral or intramuscular corticosteroid | Primary: proportion of patients improved at 12 h and 24 h post-treatment | Improvement at 12 h (OR 2·25 [1·66–3·06]) |

| Secondary: incidence of endotracheal intubation | Improvement at 24 h (OR 3·19 [1·70–5·99]) | ||||

| Reduction (OR 0·21 [0·05–0·84]) | |||||

| Russell (2004)60 | 31 | 3736 | Oral, intramuscular, or nebulised corticosteroid | Primary: change in clinical croup score 6 h after treatment | Improvement (weighted mean difference −1·2 [−1·6 to −0·8]) |

| Secondary: return to medical care; length of stay in emergency department or hospital; nebulised epinephrine treatment | Reduction (RR 0·5 [0·36–0·70]) | ||||

| Reduction (weighted mean difference 12 h [5–19]) | |||||

| Reduction (risk difference 10% [1–20]) |

Data are relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR), with 95% CI, unless otherwise stated.

Table 2.

Selected randomised controlled trials of corticosteroid versus placebo in the treatment of croup

| Patients (n) | Croup severity | Setting | Route of administration and medication | Primary outcome | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjornson (2004)87 | 720 | Mild | Emergency department | Oral dexamethasone vs placebo | Return to medical care within 7 days | Reduction (7% vs 15%, p<0·001) |

| Geelhoed (1996)88 | 100 | Mild | Emergency department | Oral dexamethasone vs placebo | Return to medical care within 7–10 days after study treatment | Reduction (0% vs 17%, p<0·01) |

| Johnson (1998)47 | 144 | Moderate to severe | Emergency department | Nebulised budesonide or intramuscular dexamethasone vs placebo | Rate of admission | Reduction (35% vs 67%, p<0·001) |

| Tibballs (1992)89 | 70 | Respiratory failure or intubated | Intensive-care unit | Oral prednisolone vs placebo | Duration of intubation | Reduction (median 98 vs 138 h, p<0·003) |

| Geelhoed (1995)90 | 80 | Moderate to severe | Admitted children | Nebulised budesonide or oral dexamethasone vs placebo | Duration of admission | Reduction (12/13 h vs 20 h, p<0·03) |

| Klassen (1994)91 | 54 | Mild to moderate | Emergency department | Nebulised budesonide vs placebo | Clinical croup score at 4 h | Improvement (18% vs 6%, p=0·005) |

Table 3.

Selected randomised controlled trials of corticosteroid treatment of croup by route of administration

| Patients (n) | Croup severity | Setting | Route of administration | Primary outcome | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nebulised vs oral or intramuscular administration | ||||||

| Geelhoed (1995)90 | 80 | Moderate to severe | Admitted children | Nebulised budesonide | Duration of admission | No difference between budesonide (13 h) and dexamethasone (13 h vs 12 h) |

| Oral dexamethasone | ||||||

| Johnson (1998)47 | 144 | Moderate to severe | Emergency department | Nebulised budesonide | Rate of admission | No difference between dexamethasone and budesonide (17% vs 35%; p=0·18) |

| Intramuscular dexamethasone | ||||||

| Klassen (1998)92 | 198 | Moderate | Emergency department | Oral dexamethasone vs nebulised budesonide vs oral dexamethasone vs nebulised budesonide | Clinical croup score at 4 h | No difference between groups (p=0·70) |

| Oral vs intramuscular administration | ||||||

| Rittichier (2000)93 | 277 | Moderate | Emergency department | Intramuscular vs oral dexamethasone | Return to medical care | No difference between groups (intramuscular 32%, oral 25%, p=0·198) |

| Donaldson (2003)94 | 96 | Moderate to severe | Emergency department | Intramuscular vs oral dexamethasone | Croup symptom resolution at 24 h | No difference between groups (intramuscular 2%, oral 8%) |

| Amir (2006)95 | 52 | Mild to moderate | Emergency department | Intramuscular dexamethasone vs oral betamethasone (note: investigator aware of study treatment) | Clinical croup score at 4 h | No difference between groups (p=0·18) |

Table 4.

Comparison of dosing in selected randomised controlled trials of corticosteroid treatment of croup

| Patients (n) | Croup severity | Corticosteroid and dose | Route of administration | Primary outcome | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fifoot (2007)96 | 99 | Mild to moderate | Dexamethasone 0·15 or 0·6 mg/kg, or prednisolone 1 mg/kg | Oral | Change in clinical croup score at 4 h | No difference between groups (p=0·4779) |

| Geelhoed (1995)97 | 120 | Moderate | Dexamethasone 0·15, 0·30, or 0·60 mg/kg | Oral | Median duration of admission | No difference between groups (9 h in 0·15 mg/kg, 7 h in 0·30 mg/kg, 8 h in 0·6 mg/kg) |

| Alshehri (2005)98 | 72 | Moderate | Dexamethasone 0·15 or 0·60 mg/kg | Oral | Change in clinical croup score at 12 h | No difference between groups (p=0·15) |

| Chub-Uppakarn (2007)99 | 41 | Moderate to severe | Dexamethasone 0·15 or 0·60 mg/kg | Intravenous | Change in clinical croup score at 12 h | No difference between groups (p=0·40) |

Compared with children not treated with corticosteroids, those with mild croup who are treated with these drugs are 50% less likely to return for medical care because of ongoing symptoms and lose 30% less sleep during the course of their illness, and their parents report less stress than do parents of children not treated with corticosteroids.87 Treatment with these drugs also yields small but clinically important societal economic benefits (family and health-care system), resulting in a total saving of CAN$21 per child.87 The benefits of treating children with mild croup arise irrespective of the duration of the child's symptoms or severity of illness.87

To date, no adverse effects have been associated with use of corticosteroids in children with croup.63 However, difficulties arise when attempting to identify and prove that rare adverse effects arise with any drug treatment; thus, remaining vigilant about this possibility is important.

Route of administration

The best route of administration of corticosteroids in children with croup has been investigated extensively. The oral or intramuscular route is either equivalent or superior to inhalation.47, 90, 92, 100, 101 The addition of inhaled budesonide to oral dexamethasone in children admitted with croup did not confer any additional advantage.102

In two trials in which oral and intramuscular administration of dexamethasone were compared, no difference was recorded in resolution of croup symptoms,93 return for medical care,93, 94 admission to hospital,93, 94 or further treatment with corticosteroid or epinephrine.94 Findings of a study comparing intramuscular dexamethasone to oral betamethasone noted no difference in reduction of croup score after treatment, hospital admission, time to symptom resolution, or return for medical care.95

Studies in which corticosteroids have been administered orally have mainly incorporated dexamethasone. Two comparator studies have been published of oral agents in the treatment of croup. In the first, one oral dose of prednisolone was compared with dexamethasone, and the findings showed superiority of dexamethasone in reducing rates of return for medical care.103 In the second study, oral dexamethasone was compared with oral prednisolone; no difference was noted in reduction of croup score or rates of return for medical care.96 A more practical consideration could be that oral dexamethasone is associated with less vomiting than oral prednisone, a substantial advantage.104

Practical issues should also be considered. For instance, for a child with persistent vomiting, the inhaled or intramuscular route for drug delivery might be preferable. In cases of severe respiratory distress, oral administration could be more difficult for the child to tolerate than an intramuscular dose. In a child with hypoxia, decreased gut and local tissue perfusion can impair absorption via the oral or intramuscular route, respectively. In these cases, the inhaled route should be considered and would also allow for administration of oxygen or racemic epinephrine concurrently. The cost of each treatment route should also be thought about.

Drug dosing

With respect to dosing of corticosteroids, two important questions should be asked. First, is one dose of dexamethasone sufficient or will several be required? Second, what is the appropriate size of dexamethasone dose: 0·15 mg/kg, 0·30 mg/kg, or 0·60 mg/kg?

We did not find any randomised trials via our literature search in which single and multiple doses of corticosteroids were compared. Published randomised trials of the effectiveness of corticosteroids are roughly split in terms of using either one dose or several. Theoretically, since most children's croup symptoms resolve within 72 h, and the speculated duration of anti-inflammatory effect of dexamethasone is 2–4 days,105 the necessity of a second dose would seem unlikely in most children with the disorder.

The conventional dose of dexamethasone is deemed to be 0·60 mg/kg. Alternatively, doses of 0·30 and 0·15 mg/kg have been proposed. Conflicting evidence for dose size is provided by a meta-analysis and the findings of four randomised trials. In the meta-analysis of six studies of children admitted to hospital, the higher the dose of hydrocortisone equivalents used the higher the proportion of children who responded to corticosteroid treatment compared with placebo.86 However, since the design of all included studies differed, the possibility of bias exists. On the other hand, four other studies in which different doses of oral dexamethasone were compared have been published; a range of croup severity and both inpatient and outpatient settings were included (table 4).96, 97, 98, 99 None of the trials was designed as a non-inferiority study and all had small sample sizes; none of the four studies showed a significant difference in primary outcome measures between corticosteroid dose sizes. The findings of these four randomised controlled trials suggest a dose of 0·15 mg/kg might be adequate whereas the systematic review meta-analysis of six studies indicates a higher dose could provide greater benefit in children with more severe disease.86

Risks of corticosteroids

Although steroid treatment of children with croup is generally known to be safe, potential concerns exist with respect to possible adverse events. First, children treated with steroids after exposure to varicella virus can have an increased risk of developing complications of varicella, such as disseminated disease or bacterial superinfection. Published case-control studies addressing this issue have yielded conflicting results. Whereas in one study, an increase in risk of complicated varicella in immunocompetent children treated with steroids was noted,106 in another this finding was not seen.107 The US Food and Drug Administration, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Allergy and Immunology advise caution in the use of steroids in children who have been exposed to varicella virus.108, 109, 110, 111 On a related issue, there is potential concern that corticosteroid use could prolong viral shedding; however, we were unable to find evidence that addresses this issue.

With steroid treatment, potential complications that have yet to be proven include bacterial tracheitis,36, 37 pneumonia, and gastrointestinal bleeding.86, 112, 113, 114 Bacterial tracheitis has been proposed to be related to previously unsuspected immune dysfunction.115 With respect to pneumonia, in a retrospective case review of 3577 immune-suppressed stem-cell transplant recipients, the most important factor associated with development of parainfluenza pneumonia was dose of corticosteroid at the time of infection acquisition.116 Gastrointestinal bleeding would seem to be unlikely in otherwise healthy children, but it could be more of a concern in a child with severe disease who requires care in the intensive-care unit, endotracheal intubation, and repeated high doses of steroids.114

Epinephrine

In children with moderate-to-severe croup, treatment with epinephrine via a nebuliser has a long history and has been well studied (table 5 ). Using historical comparisons, the administration of epinephrine in children with severe croup has been reported to have reduced the number needing intubation or tracheotomy by a substantial amount.120 Nebulised racemic epinephrine (2·25%), compared with placebo, improved croup scores within 10–30 min of initiation of treatment in three randomised controlled trials.117, 118, 119 In a fourth placebo-controlled trial, a clear benefit was not recorded; however, this trial was not well-designed nor well-reported.121 Objective pathophysiological measures of severity have also shown substantial improvement after epinephrine treatment in five prospective cohort studies.57, 58, 59, 72, 122 Clinical effect is sustained for at least 1 h,57, 58, 59, 117, 119, 121, 123 but it is essentially gone within 2 h of administration.119 Reassuringly, as the effect of epinephrine wears off, the patient's symptoms return—on average—to their baseline severity and do not seem to worsen.118, 119 Combined data from five prospective clinical trials in outpatients treated with epinephrine and dexamethasone (or budesonide) who were observed for 2–4 h are also reassuring. Of 253 children, only 12 (5%) who were discharged home returned for care within 48–72 h and only six of these were admitted to hospital (2%). No children had adverse outcomes.47, 124, 125, 126, 127 This prospectively derived data along with findings of two retrospective cohort studies provide favourable support for children to be safely discharged home after treatment with epinephrine, as long as their symptoms have not recurred within 2–4 h of treatment.128, 129

Table 5.

Selected randomised controlled trials of nebulised epinephrine versus placebo in the treatment of croup

| Patients (n) | Croup severity | Epinephrine dose | Primary outcome | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taussig (1975)117 | 13 | Moderate to severe | 0·25–1·5 mL (by weight) of 2·25% epinephrine | Clinical croup score 10 min after treatment | Improvement (p=0·011) |

| Kristjansson (1994)118 | 54 | Mild to moderately severe | Racemic epinephrine (20 mg/mL) at 0·5 mg/kg | Clinical croup score 30 min after treatment | Greater improvement in epinephrine group (p=0·003) |

| Westley (1978)119 | 20 | Moderate | 0·5 mL of 2·25% epinephrine | Clinical croup score 10, 30, and 120 min after treatment | Greater improvement in epinephrine group at 10 and 30 min (p<0·1) |

| No difference at 120 min |

The administration of one dose at a time of nebulised epinephrine to children has not been associated with any adverse effects nor a clinically significant increase in either heart rate or blood pressure.76, 99, 117, 118, 123, 130 The conclusions of a critical review of seven clinical trials of 238 children treated with nebulised epinephrine (1/1000, with 184 patients receiving doses of 3 mL or greater) for either croup or acute bronchiolitis noted that epinephrine was a safe treatment and identified only mild side-effects, including, most frequently, tachycardia and pallor.131 One case report has been published of a previously healthy child with severe croup who developed ventricular tachycardia and myocardial infarction after treatment with three doses of epinephrine via nebuliser within 1 h.132

Racemic epinephrine has traditionally been used to treat children with croup. However, epinephrine 1/1000 is as effective and safe as the racemate form, as shown by findings of a randomised trial in 31 children aged 6 months to 6 years with moderate-to-severe croup.130 In most studies, the same dose has been used in all children irrespective of size (0·5 mL of 2·25% racemic epinephrine or 5·0 mL of epinephrine 1/1000). Data derived from use of aerosolised medications in lower-airway disease supports this approach, in that the effective dose of drug delivered to the airway is regulated by every individual's tidal volume.133, 134, 135, 136

Analgesics, antipyretics, antibiotics, antitussives, decongestants, and short-acting β2 agonists

We retrieved no controlled trials of the effectiveness of any of these drugs in the treatment of croup with our literature search. The use of analgesics or antipyretics is reasonable for the benefit of reduction of fever or discomfort in children with croup.48, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 Most types of croup have a viral cause. Although so-called superinfections, such as bacterial tracheitis and pneumonia, are described, the rare frequency (<1 per 1000 cases of croup) makes use of prophylactic antibiotics unreasonable.48, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 No physiologically rational basis exists for use of antitussives or decongestants, and they should not be administered to children with croup.48, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 Similarly, in view of the pathophysiology of croup as an upper-airway disease, there is no clear reason to use short-acting β2 agonists for treatment of the disease.48, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67

Indications for admission and discharge from medical care

Although most children with croup can be managed safely as outpatients, little published evidence is available to guide clinicians as to which individuals should be admitted to hospital.48, 137, 138 Data from a retrospective cohort of 527 children admitted to Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, for persistent stridor at rest (before routine treatment with corticosteroids) showed that those with persistent sternal indrawing at presentation to an emergency department had a 6% risk for endotrachael intubation, whereas those without sternal and chest-wall indrawing recovered rapidly without any specific treatment.138 In a study comparing dexamethasone with placebo,47 recorded reductions in admissions in the dexamethasone-treated group were first noted 3 h later, with increasing differences shown up to 10 h after treatment. The rate of admission in the dexamethasone-treated group was half that of those given placebo. This finding suggests that observation in an emergency deparment for at least 3 h, and ideally up to 10 h after treatment with corticosteroid, would reduce admission rates, presumably as the beneficial effects of corticosteroids become evident with time. In a published report looking at length of stay in the emergency department and admission, a substantial reduction was recorded in admissions after implementation of a clinical pathway mandating 6 h of observation in the emergency department after corticosteroid treatment before a child with croup was admitted to hospital.137 Based on this evidence and combined with expert opinion, the Alberta Medical Association clinical pathway committee has developed and implemented the management algorithm outlined in the figure.48

Conclusion

After 50 years of controversy, corticosteroids have been firmly established as the treatment of choice for children with croup. Although comparatively fewer reports have been published on epinephrine, sufficient data exist to support the drug's role in short-term symptom relief until corticosteroids take effect. Conversely, after more than a century of use, definitive evidence is available to show the ineffectiveness of mist. Apart from heliox, no new therapeutic interventions are on the horizon. Nonetheless, corticosteroids and epinephrine have greatly reduced health-care use and enhanced outcomes in children with croup.

Although effective treatment for croup is well-established, several mysteries remain unexplained with respect to the cause and pathophysiology of the disease. Exploration of these questions could ultimately yield novel and even more effective treatments or vaccines.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched the Cochrane Library and Medline with the terms “croup”, “acute laryngotracheobronchitis”, “acute laryngotracheitis”, and “spasmodic croup”, with no date or language restrictions. We included randomised controlled trials, original studies, critical reviews, and meta-analyses of all treatments for croup. We also referred to commonly referenced and important older publications. Additionally, we reviewed bibliographies from highly relevant reports identified by our original search and from our own bibliographic databases.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest. DJ received an unrestricted research grant in 1993 from Astra Pharma, Mississauga, ON, Canada, to undertake a randomised controlled trial comparing nebulised budesonide, intramuscular dexamethasone, and placebo for moderately severe croup.47

References

- 1.Stool S. Croup syndrome: historical perspective. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7:S157–S161. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198811001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denny F, Murphy T, Clyde W, Collier A, Henderson F. Croup: an 11-year study in a pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 1983;71:871–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong M, Chu M, Leighton S, van Hasselt C. Adult croup. Chest. 1996;109:1659–1662. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.6.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marx A, Torok T, Holman R, Clarke M, Anderson L. Pediatric hospitalizations for croup (laryngotracheobronchitis): biennial increases associated with human parainfluenza virus 1 epidemics. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1423–1427. doi: 10.1086/514137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson D, Williamson J. Croup: duration of symptoms and impact on family functioning. Pediatr Research. 2001;49:83A. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orth D, Kovacs W, DeBold C Rowan. The adrenal cortex. In: Wilson J, Forster D, editors. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 8th edn. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1992. p. 504. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weitzman E, Fukushima D, Nogiere C, Roffwarq H, Gallagher T, Hellman L. Twenty-four hour pattern of the episodic secretion of cortisol in normal subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1971;33:14–22. doi: 10.1210/jcem-33-1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calhoun W. Nocturnal asthma. Chest. 2003;123:399–405. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.3_suppl.399s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman R, Henderson F, Clyde W, Collier A, Denny F. The epidemiology of tracheobronchitis in pediatric practice. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;114:786–797. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams J, Harris P, Tollefson S. Human metapneumovirus and lower respiratory tract disease in otherwise healthy infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:443–450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Hoek L, Sure K, Ihorst G. Human coronavirus NL63 infection is associated with croup. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;581:485–491. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-33012-9_86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crowe J. Current approaches to the development of vaccines against disease caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and parainfluenza virus (PIV): a meeting report of the WHO Programme for Vaccine Development. Vaccine. 1995;13:415–421. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)98266-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belshe R, Newman F, Anderson E. Evaluation of combined live, attenuated respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza 3 virus vaccines in infants and young children. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:2096–2103. doi: 10.1086/425981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapustian V, Boldyrev V, Maleev V, Mikhailova E, Sedak E. [The local manifestations of diphtheria.] Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1994;4:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Platonova T, Korzhenkova M. [Clinical aspects of diphtheria in infants.] Pediatriia. 1991;6:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pokrovskii V, Ostrovskii N, Astaf'eva N, Filimonova N. [Croup in toxic forms of diphtheria in adults.] Ter Arkh. 1985;57:199–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Havaldar P. Dexamethasone in laryngeal diphtheritic croup. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1997;17:21–23. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1997.11747858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D'Souza RM, D'Souza R. Vitamin A for preventing secondary infections in children with measles: a systematic review. J Trop Pediatr. 2002;48:72–77. doi: 10.1093/tropej/48.2.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hussey G, Klein M. A randomized, controlled trial of vitamin A in children with severe measles. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:160–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007193230304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherry J. Croup (laryngitis, laryngotracheitis, spasmodic croup, laryngotracheobronchitis, bacterial tracheitis, and laryngotracheobronchopneumonitis) In: Feigin R, editor. Textbook of pediatric infectious diseases. 5th edn. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2004. pp. 252–265. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunzelmann K, Konig J, Sun J. Acute effects of parainfluenza virus on epithelial electrolyte transport. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48760–48766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis G. An examination of the physiological consequences of chest wall distortion in infants with croup. University of Calgary; Calgary: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis G, Cooper D, Mitchell I. The measurement of thoraco-abdominal asynchrony in infants with severe laryngotracheobronchitis. Chest. 1993;103:1842–1848. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.6.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Angelo A, McGillivray D, Kramer M. Will my baby stop breathing? Pediatr Res. 2001;49:83A. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson D, Williamson J. Health care utilization by children with croup in Alberta. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:185A. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phelan P, Landau L, Olinksy A. Respiratory illness in children. Blackwell Science; Oxford: 1982. pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- 27.To T, Dick P, Young W, Hernandez R. Hospitalization rates of children with croup in Ontario. Paediatr Child Health. 1996;1:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sofer S, Dagan R, Tal A. The need for intubation in serious upper respiratory tract infection in pediatric patients (a retrospective study) Infection. 1991;19:131–134. doi: 10.1007/BF01643230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sendi K, Crysdale W, Yoo J. Tracheitis: outcome of 1 700 cases presenting to the emergency department during two years. J Otolaryngol. 1992;21:20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan A, Manoukian J. Hospitalized croup (bacterial and viral): the role of rigid endoscopy. J Otolaryngol. 1992;21:48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawson K, Mogridge N, Downward G. Severe acute laryngotracheitis in Christchurch. N Z Med J. 1991;104:374–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher J. Out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest in children with croup. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:35–36. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000106241.72265.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McEniery J, Gillis J, Kilham H, Benjamin B. Review of intubation in severe laryngotracheobronchitis. Pediatrics. 1991;87:847–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sofer S, Duncan P, Chernick V. Bacterial tracheitis: an old disease rediscovered. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1983;22:407–411. doi: 10.1177/000992288302200602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones R, Santos J, Overall J. Bacterial tracheitis. JAMA. 1979;242:721–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards K, Dundon C, Altemeier W. Bacterial tracheitis as a complication of viral croup. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1983;2:390–391. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198309000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donnelly B, McMillan J, Weiner L. Bacterial tracheitis: report of eight new cases and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:729–735. doi: 10.1093/clinids/164.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Mutairi B, Kirk V. Bacterial tracheitis in children: approach to diagnosis and treatment. Paediatr Child Health. 2004;9:25–30. doi: 10.1093/pch/9.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernstein T, Brilli R, Jacobs B. Is bacterial tracheitis changing? A 14-month experience in a pediatric intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:458–462. doi: 10.1086/514681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong V, Mason W. Branhamella catarrhalis as a cause of bacterial tracheitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:945–946. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198710000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brook I. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of bacterial tracheitis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13:16–18. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199702000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Midwinter K, Hodgson D, Yardley M. Paediatric epiglottitis: the influence of the Haemophilus influenzae b vaccine, a ten-year review in the Sheffield region. Clin Otolaryngol. 1999;24:447–448. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1999.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.GonzalezValdepena H, Wald E, Rose E, Ungkanont K, Casselbrant M. Epiglottitis and Haemophilus influenzae immunization: the Pittsburgh experience—a five-year review. Pediatrics. 1995;96:424–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorelick M, Baker M. Epiglottitis in children, 1979 through 1992: effects of Haemophilus influenzae type b immunization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148:47–50. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170010049010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tunnessen W. Respiratory system: stridor—signs and symptoms in pediatrics. JB Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Innes-Asher M. Infections of the upper respiratory tract. In: Taussig L, Landau L, editors. Pediatric respiratory medicine. Mosby; St Louis: 1999. pp. 530–547. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson D, Jacobson S, Edney P, Hadfield P, Mundy M, Schuh S. A comparison of nebulized budesonide, intramuscular dexamethasone, and placebo for moderately severe croup. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:498–503. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson D, Klassen T, Kellner J. Diagnosis and management of croup: Alberta Medical Association clinical practice guidelines. Alberta Medical Association; Alberta: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rapkin R. The diagnosis of epiglottitis: simplicity and reliability of radiographs of the neck in the differential diagnosis of the croup syndrome. J Pediatr. 1972;80:96–98. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(72)80460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swischuk L. Emergency imaging of the acutely ill or injured child. Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han B, Dunbar J, Striker T. Membranous laryngotracheobronchitis (membranous croup) Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133:53–58. doi: 10.2214/ajr.133.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Friedman E, Jorgensen K, Healy G, McGill T. Bacterial tracheitis: two-year experience. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:9–11. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stankiewicz J, Bowes A. Croup and epiglottitis: a radiologic study. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:1159–1160. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198510000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newth C, Levinson H, Bryan A. The respiratory status of children with croup. J Pediatr. 1972;81:1068–1073. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(72)80233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Margolis P, Ferkol T, Marsocci S. Accuracy of the clinical examination in detecting hypoxemia in infants with respiratory distress. J Pediatr. 1994;124:552–560. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stoney P, Chakrabarti M. Experience of pulse oximetry in children with croup. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:295–298. doi: 10.1017/s002221510011566x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Corkey C, Barker G, Edmonds J, Mok P, Newth C. Radiographic tracheal diameter measurements in acute infectious croup: an objective scoring system. Crit Care Med. 1981;9:587–590. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fanconi S, Burger R, Maurer H, Uehlinger J, Ghelfi D, Muhlemann C. Transcutaneous carbon dioxide pressure for monitoring patients with severe croup. J Pediatr. 1990;117:701–705. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steele D, Santucci K, Wright R, Natarajan R, McQuillen K, Jay G. Pulsus paradoxus: an objective measure of severity in croup. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:331–334. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9701071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Russell K, Wiebe N, Saenz A. Glucocorticoids for croup. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001955.pub2. CD001955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson D, Williamson J. Telephone out patient (TOP) score: the derivation of a telephone follow-up assessment tool for children with croup. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:185A. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chan A, Langley J, LeBlanc J. Interobserver variability of croup scoring in clinical practice. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001;6:347–351. doi: 10.1093/pch/6.6.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnson D. Croup. In: Rudolf M, Moyer V, editors. Clinical evidence. 12th edn. BMJ Publishing Group; London: 2004. pp. 401–426. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaditis A, Wald E. Viral croup: current diagnosis and treatment. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:827–834. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199809000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klassen T. Croup: a current perspective. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46:1167–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brown J. The management of croup. Br Med Bull. 2002;61:189–202. doi: 10.1093/bmb/61.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Geelhoed G. Croup. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1997;23:370–374. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199705)23:5<370::aid-ppul9>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lavine E, Scolnik D. Lack of efficacy of humidification in the treatment of croup: why do physicians persist in using an unproven modality? Can J Emerg Med. 2001;1:209–212. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500005571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neto G, Kentab O, Klassen T, Osmond M. A randomized controlled trial of mist in the acute treatment of moderate croup. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:873–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scolnik D, Coates A, Stephens D, DaSilva Z, Lavine E, Schuh S. Controlled delivery of high vs low humidity vs mist therapy for croup in emergency departments. JAMA. 2006;295:1274–1280. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.11.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bourchier D, Dawson K, Fergusson D. Humidification in viral croup: a controlled trial. Aust Paediatr J. 1984;20:289–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1984.tb00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lenny W, Milner A. Treatment of acute viral croup. Arch Dis Child. 1978;53:704–706. doi: 10.1136/adc.53.9.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Henry R. Moist air in the treatment of laryngotracheitis. Arch Dis Child. 1983;58:577. doi: 10.1136/adc.58.8.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moore M, Little P. Humidified air inhalation for treating croup. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002870.pub2. CD002870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Greally P, Cheng K, Tanner M, Field D. Children with croup presenting with scalds. BMJ. 1990;301:113. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6743.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weber J, Chudnofsky C, Younger J. A randomized comparison of helium-oxygen mixture (Heliox) and racemic epinephrine for the treatment of moderate to severe croup. Pediatrics. 2001;197:E96. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Terregino C, Nairn S, Chansky M. The effect of Heliox on croup: a pilot study. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:1130–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.DiCecco R, Rega P. The application of heliox in the management of croup by an air ambulance service. Air Med J. 2004;23:33–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amj.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McGee D, Wald D, Hinchliffe S. Helium-oxygen therapy in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1997;15:291–296. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(97)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beckmann K, Brueggemann W. Heliox treatment of severe croup. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:735–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Duncan P. Efficacy of helium-oxygen mixtures in the management of severe viral and post-intubation croup. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1979;26:206–212. doi: 10.1007/BF03006983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kemper K, Ritz R, Benson M, Bishop M. Helium-oxygen mixture in the treatment of postextubation stridor in pediatric trauma patients. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:356–359. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199103000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gupta V, Cheifetz I. Heliox administration in the pediatric intensive care unit: an evidence-based review. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:204–211. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000154946.62733.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Johnson D, Williamson J, Craig W, Klassen T. Management of croup: practice variation among 21 Alberta hospitals. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:113A. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Griffin S, Ellis S, Fitzgerald-Barron A, Rose J, Egger M. Nebulised steroid in the treatment of croup: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:135–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kairys S, Marsh-Olmstead E, O'Connor G. Steroid treatment of laryngotracheitis: a meta-analysis of the evidence from randomized trials. Pediatrics. 1989;83:683–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bjornson C, Klassen T, Williamson J. A randomized trial of a single dose of oral dexamethasone for mild croup. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1306–1313. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Geelhoed G. Sixteen years of croup in a western Australian teaching hospital: effects of routine steroid treatment. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:621–626. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tibballs J, Shann FA, Landau LI. Placebo-controlled trial of prednisolone in children intubated for croup. Lancet. 1992;340:745–748. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92293-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Geelhoed G, Macdonald W. Oral and inhaled steroids in croup: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1995;20:355–361. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950200604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Klassen T, Feldman M, Watters L, Sutcliffe T, Rowe P. Nebulized budesonide for children with mild-to-moderate croup. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:285–298. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408043310501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Klassen T, Craig W, Moher D. Nebulized budesonide and oral dexamethasone for treatment of croup: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;279:1629–1632. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rittichier K, Ledwith C. Outpatient treatment of moderate croup with dexamethasone: intramuscular versus oral dosing. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1344–1348. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Donaldson D, Poleski D, Knipple E. Intramuscular versus oral dexamethasone for the treatment of moderate-to-severe croup: a randomized, double-blind trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Amir L, Hubermann H, Halevi A, Mor M, Mimouni M, Waisman Y. Oral betamethasone versus intramuscular dexamethasone for the treatment of mild to moderate viral croup. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:541–544. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000230552.63799.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fifoot AA, Ting JY. Comparison between single-dose oral prednisolone and oral dexamethasone in the treatment of croup: a randomized, double-blinded clinical trial. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2006.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Geelhoed G, Macdonald W. Oral dexamethasone in the treatment of croup: 0·15 mg/kg versus 0·3 mg/kg versus 0·6 mg/kg. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1995;20:362–368. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950200605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Alshehri M, Almegamsi T, Hammdi A. Efficacy of a small dose of oral dexamethasone in croup. Biomed Res. 2005;16:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chub-Uppakarn S, Sangsupawanich P. A randomized comparison of dexamethasone 0·15 mg/kg versus 0·6 mg/kg for the treatment of moderate to severe croup. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pedersen L, Dahl M, Falk-Pedersen H, Larsen S. [Inhaled budesonide versus intramuscular dexamethasone in the treatment of pseudo-croup.] Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160:2253–2256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cetinkaya F, Tufekci B, Kutluk G. A comparison of nebulized budesonide, and intramuscular, and oral dexamethasone for treatment of croup. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:453–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Geelhoed G. Budesonide offers no advantage when added to oral dexamethasone in the treatment of croup. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21:359–362. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000166724.99555.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sparrow A, Geelhoed G. Prednisolone versus dexamethasone in croup: a randomised equivalence trial. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:580–583. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.089516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Qureshi F, Zaritsky A, Poirier M. Comparative efficacy of oral dexamethasone versus oral prednisone in acute pediatric asthma. J Pediatr. 2001;139:20–26. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.115021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schimmer B, Parker K. Adrenocorticotropic hormone: adrenocortical steroids and their synthetic analogs—inhibitors of the synthesis and actions of adrenocortical hormones. In: Brunton L, Lazo J, Parker K, editors. Goodman and Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. McGraw-Hill; Columbus: 2006. pp. 1587–1612. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dowell S, Bresee J. Severe varicella associated with steroid use. Pediatrics. 1993;92:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Patel H, Macarthur C, Johnson D. Recent corticosteroid use and the risk of complicated varicella in otherwise immunocompetent children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:409–414. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Anon . vol 21. US Food and Drug Administration; Rockville: 1991. Revised label warns of severe viral problems with corticosteroids. (FDA Medical Bulletin). [Google Scholar]

- 109.Anon . Draft position statement: inhaled corticosteroids and severe viral infections—news and notes. American Academy of Allergy and Immunology Committee on Drugs; Milwaukee: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Anon . New drug not routinely recommended for healthy children with chickenpox. Canadian Pediatric Society; Ottawa: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Anon . Varicella-zoster infections. In: Halsey N, Hall CB, editors. 1997 red book: report of the committee on infectious diseases. 24th edn. American Academy of Pediatrics; Elk Grove Village: 1997. p. 702. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lebel M, Freij B, Syrogiannopoulos G. Dexamethasone therapy for bacterial meningitis: results of two double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:964–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810133191502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Anene O, Meert K, Uy H, Simpson P, Sarnaik A. Dexamethasone for the prevention of postextubation airway obstruction: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1666–1669. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199610000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.McIntyre P, Berkey C, King S. Dexamethasone as adjunctive therapy in bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 1997;278:925–931. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.11.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Johnson D, Schuh S, Koren G, Jaffe D. Outpatient treatment of croup with nebulized dexamethasone. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:349–355. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nichols W, Corey L, Gooley T, Davis C, Boeckh M. Parainfluenza virus infections after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: risk factors, response to antiviral therapy, and effect on transplant outcome. Blood. 2001;98:573–578. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Taussig L, Castro O, Beaudry P, Fox W, Bureau M. Treatment of laryngotracheobronchitis (croup): use of intermittent positive-pressure breathing and racemic epinephrine. Am J Dis Child. 1975;129:790–793. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1975.02120440016004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kristjansson S, Berg-Kelly K, Winso E. Inhalation of racemic adrenaline in the treatment of mild and moderately severe croup: clinical symptom score and oxygen saturation measurements for evaluation of treatment effects. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:1156–1160. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb18270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Westley C, Cotton E, Brooks J. Nebulized racemic epinephrine by IPPB for the treatment of croup. Am J Dis Child. 1978;132:484–487. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1978.02120300044008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Adair J, Ring W, Jordan W, Elwyn R. Ten-year experience with IPPB in the treatment of acute laryngotracheobronchitis. Anesth Analg. 1971;50:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gardner H, Powell K, Roden V, Cherry J. The evaluation of racemic epinephrine in the treatment of infectious croup. Pediatrics. 1973;52:68–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sivan Y, Deakers T, Newth C. Thoracoabdominal asynchrony in acute upper airway obstruction in small children. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:540–544. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.3.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fogel J, Berg I, Gerber M, Sherter C. Racemic epinephrine in the treatment of croup: nebulization alone versus nebulization with intermittent positive pressure breathing. J Pediatr. 1982;101:1028–1031. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rizos J, DiGravio B, Sehl M, Tallon J. The disposition of children with croup treated with racemic epinephrine and dexamethasone in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1998;16:535–539. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(98)00055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ledwith C, Shea L, Mauro R. Safety and efficacy of nebulized racemic epinephrine in conjunction with oral dexamethasone and mist in the outpatient treatment of croup. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:331–337. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kunkel N, Baker M. Use of racemic epinephrine, dexamethasone, and mist in the outpatient management of croup. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1996;12:156–159. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199606000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Prendergast M, Jones J, Hartman D. Racemic epinephrine in the treatment of laryngotracheitis: can we identify children for outpatient therapy? Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12:613–616. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kelley P, Simon J. Racemic epinephrine use in croup and disposition. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:181–183. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(92)90204-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Corneli H, Bolte R. Outpatient use of racemic epinephrine in croup. Am Fam Physician. 1992;46:683–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Waisman Y, Klein B, Boenning D. Prospective randomized double-blind study comparing L-epinephrine and racemic epinephrine aerosols in the treatment of laryngotracheitis (croup) Pediatrics. 1992;89:302–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhang L, Sanguebsche L. [The safety of nebulization with 3 to 5 ml of adrenaline (1:1000) in children: an evidence based review.] J Pediatr (Rio J) 2005;81:193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Butte M, Nguyen B, Hutchison T, Wiggins J, Ziegler J. Pediatric myocardial infarction after racemic epinephrine administration. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e9. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.1.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wildhaber J, Monkhoff M, Sennhauser F. Dosage regimens for inhaled therapy in children should be reconsidered. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38:115–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Schuepp K, Straub D, Moller A, Wildhaber J. Deposition of aerosols in infants and children. J Aerosol Med. 2004;17:153–156. doi: 10.1089/0894268041457228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fink J. Aerosol delivery to ventilated infant and pediatric patients. Respir Care. 2004;49:653–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Janssens H, Krijgsman A, Verbraak T, Hop W, de Jongste J, Tiddens H. Determining factors of aerosol deposition for four pMDI-spacer combinations in an infant upper airway model. J Aerosol Med. 2004;17:51–61. doi: 10.1089/089426804322994460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chin R, Browne G, Lam L, McCaskill M, Fasher B, Hort J. Effectiveness of a croup clinical pathway in the management of children with croup presenting to an emergency department. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38:382–387. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Wagener J, Landau L, Olinsky A, Phelan P. Management of children hospitalized for laryngotracheobronchitis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1986;2:159–162. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950020308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]