When an outbreak of febrile haemorrhagic disease first occurred in the Ulge Province of Angola in November, 2004, it was the poliomyelitis surveillance officer in that province who did the initial case investigation, collected blood specimens, and ensured that those specimens were sent to a WHO Collaborating Centre for Haemorrhagic Fevers.1 After the diagnosis of Marburg haemorrhagic fever, the poliomyelitis surveillance officers provided logistic support to the national and international team that implemented containment activities, which included case finding, contact tracing, case management and infection control in adapted isolation facilities, on-site laboratory diagnosis, safe burial, and social mobilisation. In addition, all 65 poliomyelitis eradication officers in Angola, of whom six are international and the rest nationals, organised mobile teams for active surveillance in provinces at risk outside the outbreak zone to investigate and report suspect cases.

These poliomyelitis surveillance officers are part of a worldwide system for surveillance of acute flaccid paralysis that identifies, investigates, and collects specimens each year from over 60 000 paralysed children under the age of 15 years in more than 190 countries.2 The system is supported by the poliomyelitis eradication partners—Rotary International, UNICEF, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and WHO—through the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). This system, which is constantly monitored for performance against international surveillance standards, provides a structure for rapidly detecting and responding to diseases of national and international importance, and in some resource-poor countries in Africa and south Asia is the most reliable surveillance and response mechanism available.

Poliomyelitis surveillance officers also support countries in planning, social mobilisation, and implementation of poliovirus vaccination campaigns; and they train school teachers and community volunteers to participate in vaccination campaigns along with health workers. Vaccination coverage of more than 90% is usually attained, providing near-universal access to oral poliovirus vaccine, with performance assessed by independent monitors.

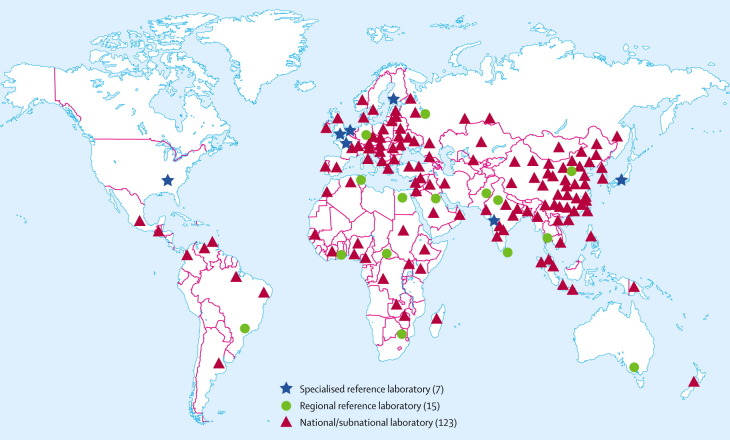

Surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis is underpinned by a network of 145 laboratories in 90 countries that isolate and genetically characterise polioviruses, providing an understanding of their geographical distribution and guiding response activities.3 These laboratories, some of which receive external financial support from GPEI, use standard equipment, reagents, and methods. They must be reaccredited every 1–2 years to remain in the network, and are distributed around the world (figure ).

Figure.

Laboratory network for poliomyelitis surveillance4

There are 279 international and 2964 national GPEI-funded poliomyelitis eradication staff in over 50 countries with or at risk of wild poliovirus infection (table ). These staff are concentrated in areas with the weakest health systems. Mainly because of financing constraints, the number of GPEI-funded surveillance officers is systematically reduced as countries are certified poliomyelitis-free, with some transferred to other international funding sources (eg, for activities to reduce measles mortality) or national government service. Poliomyelitis surveillance officers are usually medical epidemiologists who have been specially trained in poliomyelitis surveillance, case investigation and outbreak response, and are equipped with computers, transport, and real-time communication capacity through cell or satellite phones.

Table.

Poliomyelitis eradication staff supported by Global Polio Eradication Initiative

| WHO Region | International Staff | National Staff | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| African | 151 | 946 | 1097 |

| American | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 96 | 839 | 935 |

| European | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| South East Asian | 25 | 1167 | 1192 |

| Western Pacific | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 279 | 2964 | 3243 |

Data are from the WHO Polio Eradication Initiative.

In over 125 countries, the epidemiological and laboratory capacities have been broadened to include diseases such as measles, yellow fever, the haemorrhagic fevers, meningitis, and Japanese encephalitis.4 The network has also been mobilised to support countries during the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Most recently, capacities have been broadened to include avian influenza. For example, in Kaduna State in Nigeria, poliomyelitis surveillance officers provided key messages about avian influenza to community leaders during poliomyelitis vaccination campaigns in early February, and poliomyelitis surveillance officers are now providing such messages throughout Nigeria. Poliomyelitis surveillance officers in Maharashtra State in India have been asked to report any information they obtain on sick or dying poultry to federal health authorities.

Further broadening the epidemiological capacities of poliomyelitis surveillance officers by providing training in influenza can substantially enhance surveillance and investigation of severe respiratory disease in human beings living in areas where there are lethal outbreaks in poultry and, potentially, assist in the early detection of avian disease. Broadening the laboratory capacity to include diagnosis of H5N1 where feasible could provide wider support to the influenza-laboratory network. Should there be a need for rapid and effective social mobilisation and distribution of antiviral drugs or eventually vaccines, the capacity of the poliomyelitis eradication officers to ensure access is proven.

External support for national poliomyelitis surveillance is presently borne entirely by GPEI, with about US$100 million in annual funding from donor countries, multilateral institutions, foundations, and Rotary International. Broadening the funding base for this unique international public-health surveillance and laboratory network could maintain its geographical distribution and ensure a stronger response capacity for any national or international pandemic of influenza. To ignore this dividend of the 20-year international investment in poliomyelitis eradication will increase vulnerability to avian influenza in countries where health systems are weakest and least able to detect and respond.

Acknowledgments

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Anon Marburg haemorrhagic fever in Angola—update. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:141–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heymann DL, Aylward RB. Global health: eradicating polio. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1275–1277. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heymann DL, de Gourville EM, Aylward RB. Protecting investments in polio eradication: the past, present and future of surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132:779–780. doi: 10.1017/s0950268804002638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anon Acute flaccid paralysis surveillance: a global platform for detecting and responding to priority infectious diseases. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2004;79:425–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]