Abstract

Background

Smokers have a substantially increased risk of postoperative complications. Preoperative smoking intervention may be effective in decreasing this incidence, and surgery may constitute a unique opportunity for smoking cessation interventions.

Objectives

The objectives of this review are to assess the effect of preoperative smoking intervention on smoking cessation at the time of surgery and 12 months postoperatively, and on the incidence of postoperative complications.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register in January 2014.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials that recruited people who smoked prior to surgery, offered a smoking cessation intervention, and measured preoperative and long‐term abstinence from smoking or the incidence of postoperative complications or both outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

The review authors independently assessed studies to determine eligibility, and discussed the results between them.

Main results

Thirteen trials enrolling 2010 participants met the inclusion criteria. One trial did not report cessation as an outcome. Seven reported some measure of postoperative morbidity. Most studies were judged to be at low risk of bias but the overall quality of evidence was moderate due to the small number of studies contributing to each comparison.

Ten trials evaluated the effect of behavioural support on cessation at the time of surgery; nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) was offered or recommended to some or all participants in eight of these. Two trials initiated multisession face‐to‐face counselling at least four weeks before surgery and were classified as intensive interventions, whilst seven used a brief intervention. One further study provided an intensive intervention to both groups, with the intervention group additionally receiving a computer‐based scheduled reduced smoking intervention. One placebo‐controlled trial examined the effect of varenicline administered one week preoperatively followed by 11 weeks postoperative treatment, and one placebo‐controlled trial examined the effect of nicotine lozenges from the night before surgery as an adjunct to brief counselling at the preoperative evaluation. There was evidence of heterogeneity between the effects of trials using intensive and brief interventions, so we pooled these separately. An effect on cessation at the time of surgery was apparent in both subgroups, but the effect was larger for intensive intervention (pooled risk ratio (RR) 10.76; 95% confidence interval (CI) 4.55 to 25.46, two trials, 210 participants) than for brief interventions (RR 1.30; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.46, 7 trials, 1141 participants). A single trial did not show evidence of benefit of a scheduled reduced smoking intervention. Neither nicotine lozenges nor varenicline were shown to increase cessation at the time of surgery but both had wide confidence intervals (RR 1.34; 95% CI 0.86 to 2.10 (1 trial, 46 participants) and RR 1.49; 95% CI 0.98 to 2.26 (1 trial, 286 participants) respectively). Four of these trials evaluated long‐term smoking cessation and only the intensive intervention retained a significant effect (RR 2.96; 95% CI 1.57 to 5.55, 2 trials, 209 participants), whilst there was no evidence of a long‐term effect following a brief intervention (RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.75, 2 trials, 341 participants). The trial of varenicline did show a significant effect on long‐term smoking cessation (RR 1.45; 95% CI 1.01 to 2.07, 1 trial, 286 participants).

Seven trials examined the effect of smoking intervention on postoperative complications. As with smoking outcomes, there was evidence of heterogeneity between intensive and brief behavioural interventions. In subgroup analyses there was a significant effect of intensive intervention on any complications (RR 0.42; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.65, 2 trials, 210 participants) and on wound complications (RR 0.31; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.62, 2 trials, 210 participants). For brief interventions, where the impact on smoking had been smaller, there was no evidence of a reduction in complications (RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.72 to 1.19, 4 trials, 493 participants) for any complication (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.40, 3 trials, 325 participants) for wound complications. The trial of varenicline did not detect an effect on postoperative complications (RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.52 to 1.72, 1 trial, 286 participants).

Authors' conclusions

There is evidence that preoperative smoking interventions providing behavioural support and offering NRT increase short‐term smoking cessation and may reduce postoperative morbidity. One trial of varenicline begun shortly before surgery has shown a benefit on long‐term cessation but did not detect an effect on early abstinence or on postoperative complications. The optimal preoperative intervention intensity remains unknown. Based on indirect comparisons and evidence from two small trials, interventions that begin four to eight weeks before surgery, include weekly counselling and use NRT are more likely to have an impact on complications and on long‐term smoking cessation.

Keywords: Humans, Preoperative Care, Smoking Cessation, Benzazepines, Benzazepines/administration & dosage, Nicotine, Nicotine/administration & dosage, Nicotinic Agonists, Nicotinic Agonists/administration & dosage, Postoperative Complications, Postoperative Complications/prevention & control, Quinoxalines, Quinoxalines/administration & dosage, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Smoking, Smoking/adverse effects, Tobacco Use Cessation Devices, Varenicline

Plain language summary

Can people be helped to stop smoking before they have surgery?

Smoking is a well‐known risk factor for complications after surgery. Stopping smoking before surgery is likely to reduce the risk of complications. We reviewed the evidence about the effects of providing smoking cessation interventions to people awaiting surgery on their success in quitting at the time of surgery and longer‐term, and at complications following surgery. The evidence is current to January 2014.

We searched for randomized studies enrolling people who smoked and were awaiting any type of planned surgery. The trials tested interventions to encourage and help them to stop smoking before surgery. Interventions could include any type of support, including written materials, brief advice, counselling, medications such as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or varenicline, and combinations of different methods. The control could be usual care or a less intensive intervention.

We found 13 studies which met the inclusion requirements. The overall quality of evidence was moderate, limited by the small number of studies contributing to key analyses. Participants were awaiting a range of different types of surgery. Interventions differed in their intensity, and in how long before surgery they began. Both brief (seven trials, 1141 participants) and intensive (two trials, 210 participants) behavioural interventions were effective in increasing the proportion of smokers who were not smoking at the time they had surgery. The two trials using intensive interventions which started four to eight weeks before surgery had larger effects. Six trials of behavioural interventions assessed postoperative complications. Both trials of intensive interventions (210 participants) detected a reduction in complications in people receiving intervention, but the combined results of the four trials of brief interventions did not show a significant benefit. Only four trials of behavioural interventions followed up participants at twelve months. The two intensive interventions (209 participants) reduced the number of people smoking but the two brief interventions (341 participants) no longer showed a difference in the number of smokers. One trial of varenicline (286 participants), a pharmacotherapy shown to assist quitting in other groups of smokers, showed a benefit on cessation after twelve months, but did not show a benefit at the time of surgery or affect complications. In this trial smokers were only asked to stop the day before surgery.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Behavioural intervention versus control for preoperative smoking cessation.

| Behavioural intervention versus control for preoperative smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People awaiting surgery Settings: Preoperative assessment clinics and similar settings Intervention: Behavioural intervention (typically including provision or offer of nicotine replacement therapy) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk1 | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Behavioural intervention versus control | |||||

| Smoking cessation at time of surgery ‐ Intensive behavioural intervention (multiple contacts, initiated at least 4 weeks before surgery) Follow‐up: 0 to 4 weeks | Study population | RR 10.76 (4.55 to 25.46) | 210 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | Effect on smoking cessation was smaller but still apparent at 12‐month follow‐up (RR 2.96 95% CI 1.57 to 5.55, 209 participants, 2 studies) | |

| 47 per 1000 | 508 per 1000 (215 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 48 per 1000 | 516 per 1000 (218 to 1000) | |||||

|

Smoking cessation at time of surgery ‐ Brief behavioural intervention Follow‐up: 0 to 4 weeks |

Study population | RR 1.3 (1.16 to 1.46) | 1141 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Effect on smoking cessation was not sustained at 12‐month follow‐up (RR 1.09 95% CI 0.68 to 1.75, 341 participants, 2 studies) | |

| 373 per 1000 | 484 per 1000 (432 to 544) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 157 per 1000 | 204 per 1000 (182 to 229) | |||||

| Postoperative morbidity: Any complication ‐ Intensive intervention | Study population | RR 0.42 (0.27 to 0.65) | 210 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | Risk of postoperative complications will depend on type of operation and participants' characteristics | |

| 462 per 1000 | 268 per 1000 (162 to 337) | |||||

| Postoperative morbidity: Any complication ‐ Brief intervention | Study population | RR 0.92 (0.72 to 1.19) | 493 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | Small effect on smoking cessation was not associated with a reduction in postoperative complications | |

| 308 per 1000 | 283 per 1000 (222 to 367) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk1 (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Assumed control group quit rate based on crude averages. The expected quit rate amongst controls will depend on population characteristics, the definition of cessation, and the level of support for cessation as part of usual care. 2Imprecise estimate based on 2 moderate sized studies 3Imprecise estimate based on 4 moderate sized studies

Background

Complications related to anaesthesia and surgery are important to patients and expensive for the healthcare system. Postoperative complications result in increased morbidity and mortality, and extended hospital stay and convalescence.

Five to ten per cent of a population may annually undergo surgery and anaesthesia. Pulmonary or cardiovascular complications occur in up to 10% of the cases (Pedersen 1994), with people who smoke having a considerably increased risk of intra‐ and postoperative complications (Bluman 1998). In a retrospective study, smokers were found to have a three‐ to six‐fold increased risk of intra‐operative pulmonary complications (Akrawi 1997; Schwilk 1997). Smokers with chronic heart or lung disease have a two‐ to five‐fold increased risk of perioperative complications.

Smoking has many effects on heart function and circulation, both in the short and long term. Short‐term effects may be due to increased amounts of carbon monoxide (CO) and nicotine in the blood. The harmful effects of these substances disappear 24 to 48 hours after smoking cessation (Kambam 1986; Pearce 1984). The long‐term effects include the development of generalized atherosclerotic changes in the vasculature. Short‐term effects are more significant in those who suffer from generalized atherosclerosis (Klein 1984; Nicod 1984; Sheps 1990). The harmful effects of CO are primarily caused by its effect on oxygen metabolism, because CO binds to the haemoglobin molecules instead of oxygen, which reduces the availability of oxygen to the tissues by 3% to 12% (Pearce 1984). Furthermore, CO changes the structure of the haemoglobin molecules, shifting the oxygen‐haemoglobin curve to the left, further reducing oxygen availability, and also increases the risk of cardiac arrhythmias (Sheps 1990). Nicotine stimulates the surgical stress response and increases blood pressure, pulse rate and systemic vascular resistance, increasing the work of the heart. In summary, the effects of nicotine and CO in common tend to create an imbalance between oxygen consumption and oxygen availability in smokers (Kaijser 1985; Roth 1960). The effect of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) on oxygen consumption is unclear (Benowitz 1997; Keeley 1996). A recent study demonstrated a significant increase in tissue oxygen and a limited vasoactive effect of NRT when administered intravenously (Sørensen 2008). There is no evidence indicating that NRT negatively affects postoperative outcome (Sørensen 2003c; Sørensen 2012). NRT must therefore be considered a better alternative than smoking.

As anaesthesia and surgery cause an increased strain on cardiac and circulatory functions, an existing oxygen imbalance can be worsened in patients who smoke, potentially resulting in hypoxaemia in vital organs.

Smoking also impairs pulmonary function. Smokers have increased mucus production, with damage to the tracheal cilia, which impedes the clearance of mucus. This is the explanation for the accumulation of mucus in the airways, which eventually may lead to pulmonary infections (Lourenco 1971). These effects may be exaggerated by reductions in immune function associated with smoking (Cohen 1993; Pearce 1984; Sørensen 2004). Immobilization during surgery and anaesthesia and in the immediate postoperative period worsens the reduced pulmonary function and the mucus accumulation. Pulmonary function generally improves after approximately eight weeks of smoking cessation (Bode 1975; Buist 1976; Camner 1973; McCarthy 1972, Mitchell 1982). In a retrospective study in people undergoing pulmonary surgery, Nakagawa 2001 found that the risk of postoperative pulmonary complications was significantly higher compared to never‐smokers for both current smokers and for recent smokers who had been smoke‐free for two to four weeks before their operation. Warner 1989 found, in a prospective, descriptive and uncontrolled study, that people who stopped smoking about eight weeks prior to operation reduced their risk of postoperative pulmonary complications. The optimal timing of smoking cessation before surgery to reduce postoperative pulmonary complications remains poorly defined (Mason 2009).

Smoking impairs wound healing after surgery (Haverstock 1998; Jorgensen 1998, Silverstein 1992; Sørensen 2002), and has been shown to increase the risk of anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery (Sørensen 1999).

Shannon‐Cain 2002 found that surgical patients were not routinely informed of the risk of tobacco use or the potential of benefit of abstinence before their surgery, and concluded that the preoperative period might be a window for smoking intervention. Owen 2007 found that patients were largely not referred preoperatively to smoking cessation services, and that non‐vascular surgeons underestimated the potential benefit of preoperative smoking cessation on postoperative outcome.

The potential reduction of complications would be related to the success rate of a preoperative smoking cessation intervention. Motivation for smoking cessation might be increased, if a potential reduction of complications is possible (Møller 2004; Thomsen 2009). On the other hand, some patients tend to be nervous immediately prior to and after surgery and might feel that they need to smoke during this period, in order to deal with the stress of impending surgery and waiting for the results of the surgery (Møller 2004; Thomsen 2009). Brief smoking interventions delivered within routine daily care may not be powerful enough to influence highly dependent smokers (Hajek 2002). More intensive interventions may be required (Rice 2013; Rigotti 2012).

A successful preoperative smoking intervention could potentially reduce perioperative complications and lead to long‐term health gains if cessation were sustained.

Objectives

The objectives of this review are to assess the evidence for an effect of preoperative smoking intervention on smoking cessation at surgery and 12 months postoperatively, and on the incidence of postoperative complications.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

Smokers of any age, who are scheduled for elective surgery.

Types of interventions

Any preoperative intervention to help people awaiting surgery to stop smoking. We considered any intervention, whether brief or more intensive, with or without face‐to‐face contact, using behavioural or pharmacological or combination strategies, initiated at least 48 hours before the operation. We did not consider trials of intra‐operative and postoperative smoking interventions for inclusion.

Types of outcome measures

Smoking cessation:

Prevalence of smoking cessation at the time of surgery, and 12 months postoperatively. We used the most conservative measure of quitting at surgery and at 12 months postoperatively, i.e. we preferred self‐reported continuous abstinence to self‐reported point prevalence abstinence.

Morbidity and mortality:

Wound‐related complications; secondary surgery; cardiopulmonary complications; admission to intensive care; intra‐ and postoperative mortality; length of stay as assessed in included studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the specialized register of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, using the topic‐related terms 'pre?operative' or 'post?operative' or 'surgery' or 'operation?' or 'operative' or 'an?esthesia' in text or keyword fields. See Appendix 1 for search strategy. At the time of the most recent search on 14th January 2014 the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), 2013, Issue 12; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20140103; EMBASE (via OVID) to week 201352; PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20131230. See the Specialized Register section of the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in The Cochrane Library for full details of search strategies for this resource. For previous versions of this review there were additional searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL, combining topic‐related and smoking‐related keywords (see Appendix 2). Since these had not retrieved any additional trials in previous updates we did not rerun them for this update.

Data collection and analysis

Three authors (TT, AAM and NV) evaluated all references identified as potentially relevant. Records retrieved by the register search were prescreened by the Tobacco Addiction Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator. All authors retrieved in full and appraised all relevant studies identified from abstracts. We resolved disagreement by consensus.

We report the following information about each study in the table Characteristics of included studies.

Country; site

Type of surgical procedure if reported

Method of randomization and adequacy of concealment

Number and characteristics of study participants

Therapist types

Description of experimental interventions, including timing and duration in relation to operation; description of control interventions

Outcomes: definition of smoking abstinence at each follow‐up point, use of biochemical validation

Data on postoperative complications.

Evaluation of risk of bias

We evaluated studies according to The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias. Items in the 'Risk of bias' table were judged to be at 'low risk of bias' , 'unclear risk of bias', or 'high risk of bias' for each study. Blinding of participants in smoking cessation trials involving behavioural interventions alone is not possible, and complete blinding of personnel is considered difficult to uphold. We therefore judged blinding as adequate if outcome assessors were blinded. We considered blinding of participants and personnel prerequisite for a judgement of low risk of bias in studies evaluating pharmacotherapy interventions.

Analysis of data

We have reported relevant outcomes in the text as percentages. For graphical display and pooling we have expressed the outcomes as a risk ratio (RR). For beneficial outcomes a value greater than one indicates that the intervention is better than the control, that is, the rate of quitting is higher in the intervention than in the control group. For unfavourable outcomes such as wound infection, a value less than one indicates that the intervention is better, that is, risk of an unfavourable outcome is lower in the intervention group.

We calculated RRs for smoking cessation and postoperative complications using intention‐to‐treat and available‐case analysis (Higgins 2011). For the smoking cessation outcome, we used as the denominators the number of participants randomized, excluding those whose surgery was cancelled or postponed, those who were erroneously included, those who withdrew from the trial immediately after randomization before receiving any intervention, and finally those who died. We assumed those otherwise lost to follow‐up to be smokers (Higgins 2011). For the complications outcome we used data only on those whose results were known, using as the denominator the total number of people who had data recorded for the outcome in question.

Where it was appropriate to pool studies, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect method for combining RRs, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used two tests for heterogeneity: the Chi‐squared test for heterogeneity, with P < 0.1 considered significant, and the I² statistic, with values above 75% interpreted as considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). The I² statistic can be interpreted as the proportion of total variation observed between the studies attributable to differences between studies rather than to sampling error (chance) (Higgins 2003).

To assess the impact of missing data, we performed sensitivity analyses excluding trials with more than 20% drop‐out. We also performed sensitivity analyses excluding trials that did not supplement self‐reported smoking cessation with biochemical evaluation in order to explore any potential impact on smoking cessation at the time of surgery and at 12‐month follow‐up.

We pooled trials of behavioural interventions and trials of different pharmacotherapies separately. There is evidence that high‐intensity interventions support successful smoking cessation while briefer interventions have a non‐significant effect on smoking cessation in hospitalised people (Rigotti 2012). We further hypothesized that successful smoking cessation is a prerequisite for reducing complications. In the first version of this review we conducted exploratory subgroup analyses to assess potential differences in smoking cessation and postoperative complications in surgical patients receiving intensive versus brief preoperative interventions. We regarded intensive interventions as consisting of weekly counselling sessions over a period of four to eight weeks. Intensive and brief interventions are now pooled separately for all outcomes, and these subgroups are no longer treated as exploratory.

Earlier versions of this review reported effects as odds ratios. The Tobacco Addiction Group now recommends the use of risk ratios as being easier to interpret.

Results

Description of studies

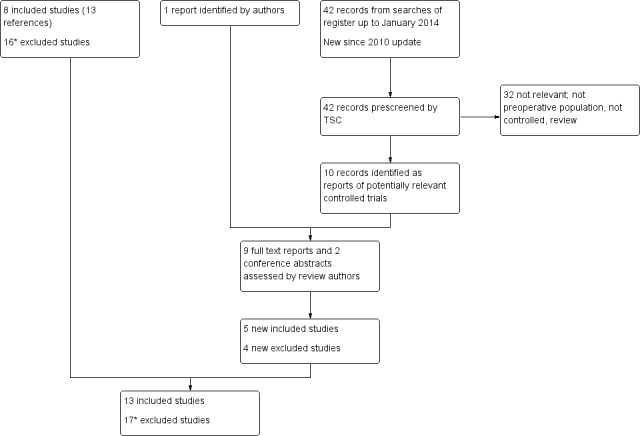

We retrieved 42 new records by searches of the Tobacco Addiction Group specialized register for this update, of which 10 were potentially relevant reports of trials. The review authors identified one additional study report (Warner 2012). We include five new studies and we add four to the list of excluded studies. (Flow diagram Figure 1). We now include 13 trials conducted in Denmark, Australia, Canada, the USA, the UK and Sweden between 2002 and 2013 in the review. Two studies had different outcomes reported in additional papers. Møller 2002 reported long‐term follow‐up in Villebro 2008, and Lindström 2008 reported postoperative outcomes in Sadr Azodi 2009. We report outcomes using the main study identifiers (Møller 2002; Lindström 2008) with the other papers shown as secondary references.

1.

Flow diagram of searches for 2013 update.

*3 previously excluded reports now listed as secondary references to other studies

Trial participants

The type of surgery and the timing of enrolment in relation to surgery was very varied. Møller 2002 enrolled 120 participants six to eight weeks before scheduled elective hip or knee joint replacement. Sørensen 2003a enrolled 60 participants two to three weeks before colorectal surgery involving an enteric anastomosis. Ratner 2004 enrolled 237 participants attending a presurgical assessment clinic one to three weeks prior to cardiovascular, ophthalmologic, plastic and urologic surgery. Wolfenden 2005 enrolled 210 participants attending a preoperative clinic one to two weeks prior to non‐cardiac surgery (nervous, ear, nose, throat, digestive, hepatobiliary, pancreas, musculoskeletal, connective tissue, skin, subcutaneous tissue, breast, gynaecologic systems). Andrews 2006 enrolled 102 participants four weeks prior to elective surgery (type of surgery not specified). Sørensen 2007 enrolled 180 participants at least four weeks prior to elective open incisional or inguinal day‐case herniotomy. Additionally, they recruited another 64 people who smoked as a control group, some before and some after the trial period. The latter group is not included in the analyses because of the absence of randomization. Lindström 2008 enrolled 117 participants at least four weeks prior to elective inguinal and umbilical hernia repair, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, or a hip or knee prosthesis. Thomsen 2010 enrolled 130 participants at least one week prior to elective breast cancer surgery. Wong 2012 enrolled 286 participants who were scheduled for elective general, orthopedic, urologic, plastic, gynaecologic, ophthalmologic or neurosurgical procedures within eight to 30 days. Warner 2012, a pilot study, enrolled 46 participants scheduled for a wide variety of elective surgical procedures and evaluated in a preoperative evaluation centre; the time from evaluation to surgery was not specified. Lee 2013 enrolled 168 participants at least three weeks prior to elective surgery in connection with their preadmission evaluation. Participants were scheduled for general, gynaecologic, urologic, ophthalmologic, otolaryngologic and orthopaedic surgery. Ostroff 2013 enrolled 185 smokers with newly‐diagnosed cancer and scheduled for surgery no less than seven days from study entry. Participants needed to have sufficient visual acuity and manual dexterity to use a handheld computer. Cancer sites included thoracic, head and neck, breast, gynaecology, urology and other. Shi 2013 enrolled 169 participants attending a preoperative evaluation centre.

Interventions

Eleven trials evaluated behavioural interventions, with pharmacotherapy offered in some. Two trials evaluated pharmacotherapy alone.

Behavioural interventions

Two trials (Møller 2002; Lindström 2008) were classified as tests of intensive interventions because they offered weekly face‐to‐face or telephone counselling over a period of four to eight weeks prior to surgery. Møller 2002 counselled participants face‐to‐face on a weekly basis over a period of six to eight weeks. Lindström 2008 counselled participants either face‐to‐face or by telephone on a weekly basis over a period of four weeks. Additionally, participants were provided with the telephone number to a quitline. Both trials also offered nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) to intervention participants. In both trials the control group participants received standard care with little or no information about smoking cessation or the potential harm of tobacco smoking.

Eight trials provided brief behavioural interventions, of which six also offered NRT to some or all participants (Sørensen 2003a; Sørensen 2007; Ratner 2004; Wolfenden 2005; Thomsen 2010; Lee 2013). Sørensen 2003a called participants the day after expected smoking cessation, provided one counselling session before surgery and informed participants that they were free to call for additional telephone support during normal working hours. Ratner 2004 offered one 15‐minute face‐to‐face counselling session and provided participants with a telephone number to call for further assistance. Wolfenden 2005 offered one interactive counselling session lasting 17 minutes via computer, one telephone counselling call, and nursing and anaesthetic staff were prompted via computer to provide brief advice. Only participants who smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day (CPD) were offered NRT. Andrews 2006 sent a letter stating that stopping smoking before surgery has huge benefits such as less time for recovery, lower chance of wound infection, and containing information on contact details of a smoking cessation service. Sørensen 2007 counselled participants one month before surgery, either face‐to‐face in a 20‐minute meeting, including advice to use NRT, or via a 10‐minute telephone reminder. Thomsen 2010 offered one counselling session lasting between 45 and 90 minutes. Shi 2013 provided all participants with brief advice about smoking cessation from trained counsellors, and informed intervention participants that their exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) level would be checked on the morning of surgery. Lee 2013 provided five minutes of counselling by a trained preadmission nurse and referral to the Canadian Cancer Society's Smokers' Helpline which initiated contact with participants and provided counselling. Various control conditions were offered in these eight trials of brief interventions. Andrews 2006, Sørensen 2007 and Thomsen 2010 gave standard advice about the risks of smoking in relation to surgery. Ratner 2004 and Lee 2013 gave standard care with inconsistent or unco‐ordinated advice. Wolfenden 2005 gave clinical staff the option to provide smoking cessation advice and prescribe NRT to control group participants. Sørensen 2003a asked control group participants to maintain daily smoking habits. Shi 2013 gave the same brief advice to intervention and control groups.

Ostroff 2013 evaluated the additional effect of a scheduled reduced smoking regimen (SRS) as an adjunct to an intensive behavioural intervention The best practice programme consisted of five individual counselling sessions with trained smoking cessation counsellors and NRT at no cost. SInce this intensive intervention was provided to all participants it was not pooled with other behavioural intervention studies.

Pharmacotherapy interventions

Placebo‐controlled trials evaluated nicotine lozenges (Warner 2012) and varenicline (Wong 2012). Warner 2012 provided brief advice (two minutes) encouraging abstinence from smoking after 7pm the night before surgery and including the potential benefits of abstinence; following this, intervention participants received 16 active nicotine lozenges. Wong 2012 set a target quit date 24 hours before surgery and instructed participants to initiate varenicline exactly one week before the target quit date. Varenicline was provided for 12 weeks. All participants received two 15‐minute standardized counselling sessions, one at the preoperative clinic and one shortly after surgery.

Outcomes

Smoking cessation

Smoking cessation was defined as either self‐reported point prevalence or self‐reported continuous abstinence (see table Characteristics of included studies for further details). Two studies did not biochemically validate self‐reported smoking cessation (Wolfenden 2005; Andrews 2006). All but one study (Sørensen 2003a) assessed smoking status at the time of surgery. Sørensen 2003a did not distinguish between cessation and reduction; we have therefore not included these combined data in the review. Five studies assessed cessation at 12 months (Møller 2002; Ratner 2004; Lindström 2008; Thomsen 2010; Wong 2012).

Postoperative complications

Postoperative complications were defined as a composite outcome, and as wound‐related, cardiopulmonary and other complications requiring treatment. Seven studies assessed complications of surgery (Møller 2002; Sørensen 2003a; Sørensen 2007; Lindström 2008; Thomsen 2010; Wong 2012; Lee 2013).

Excluded studies

Of the possibly eligible studies, six were excluded because they involved preoperative smoking cessation interventions but did not use random allocation to intervention and control groups (Basler 1981; Munday 1993; Haddock 1997); Rissel 2000 used historical controls; Moore 2005 and Sachs 2012 used a prospective cohort design. Four were excluded because the intervention was delivered in the postoperative period (Wewers 1994; Simon 1997; Griebel 1998; Nåsell 2010). One study evaluated a training intervention for surgical residents and did not have patient‐based outcomes (Steinemann 2005). One study evaluated a multicomponent intervention including drinking, obesity and physical activity in addition to smoking, and recruited both smokers and nonsmokers. It did not evaluate perioperative outcomes (McHugh 2001).

We excluded one study (Myles 2004) comparing bupropion to placebo for preoperative cessation because there were high levels of drop‐out in each group, and only a small number of those who remained in the study were admitted for surgery within the six‐month study period. Data on perioperative cessation and complications were available for only 20 of the 47 people originally randomized. Cessation rates and wound infection rates were low and similar in each group.

We excluded one study because the intervention consisted of the application of a nicotine patch immediately before surgery with no additional counselling (Warner 2005).

We excluded Warner 2011 because the primary outcome was the use rate of a quitline service. Abrishami 2010 did not include outcomes relevant for this review.

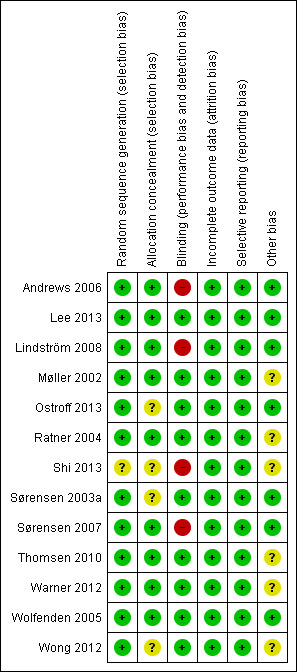

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias across domains for each study is summarised in Figure 2. All studies reported a method for random sequence generation and allocation concealment that we judged adequate to avoid selection bias. Seven studies explicitly reported blinding of assessors (Møller 2002; Sørensen 2003a; Ratner 2004; Wolfenden 2005; Wong 2012; Warner 2012; Lee 2013). In the remaining six studies, outcome assessment was not regularly blinded; Andrews 2006, Ostroff 2013 and Shi 2013 did not report using blinded outcome assessment; Sørensen 2007 used a study nurse to initially evaluate wound infections; Thomsen 2010 and Lindström 2008 used parallel blinded and unblinded outcome assessment. These studies may therefore be at some risk of detection bias. In all studies, smoking cessation was self‐reported.Nine studies validated self‐reported smoking cessation with measurements of CO in exhaled air and/or cotinine in urine/saliva. Five of nine studies did so at the time of surgery (Møller 2002; Ratner 2004; Sørensen 2007; Lindström 2008; Thomsen 2010; Warner 2012; Lee 2013; Ostroff 2013; Shi 2013); three of five studies at 12‐month follow up (Møller 2002; Ratner 2004; Wong 2012). Møller 2002, however, only did so partly in people participating in focus‐group interviews. Drop‐out rates in the included studies ranged from 1% to 29%. One study (Ratner 2004) had more than 20% drop‐out. All studies recruited participants on the basis of a convenience sample. Participation rates (i.e. the proportion of those eligible and approached who agreed to take part in the trial) were reported in all but one study (Andrews 2006), and ranged from 31% to 96%. Participants were similar across interventions in terms of baseline smoking data and comorbidity. Thomsen 2010 found a longer duration of surgery in intervention participants, which may have introduced a difference between groups in postoperative complications. Lee 2013 likewise found slightly more diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease in the intervention group.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Effect on smoking behaviours

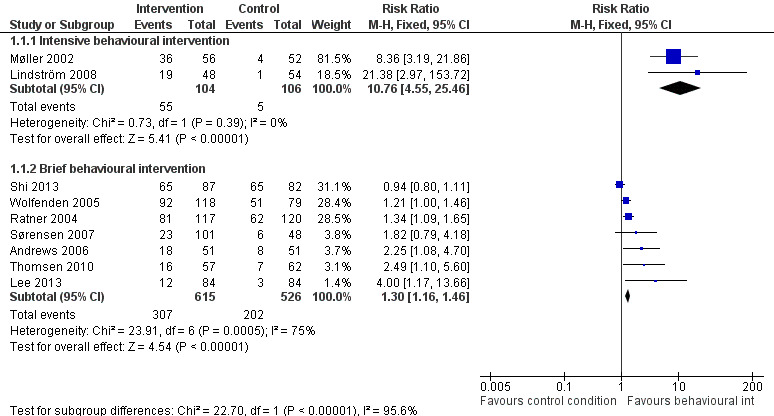

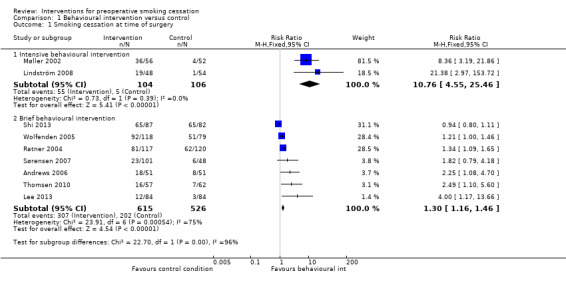

Cessation at the time of surgery

Of the 10 studies evaluating behavioural interventions versus a control, nine reported cessation outcomes. In six studies (Møller 2002; Ratner 2004; Andrews 2006; Lindström 2008; Thomsen 2010; Lee 2013), the intervention achieved a significant increase in smoking cessation at the time of surgery, and one had a lower confidence interval (CI) of 1 (Wolfenden 2005). We identified substantial heterogeneity (I² = 87%) amongst the nine studies, so we did not consider pooling of all results appropriate. Heterogeneity was lower when we grouped the studies by the intensity of the intervention. We therefore pooled these subgroups (Figure 3; Analysis 1.1). Pooling the two trials (210 participants) using intensive interventions (Møller 2002; Lindström 2008) gave a RR of 10.76; 95% CI 4.55 to 25.46, and no evidence of heterogeneity. The pooled estimate for the six trials of brief interventions was smaller but also excluded no effect (RR 1.30; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.46; 1141 participants). There was still marked heterogeneity (I² = 75%). Exclusion of Shi 2013, in which the only difference between groups was measurement of exhaled CO on the morning of surgery, increased the point estimate to RR 1.47; 95% CI 1.27 to 1.70, and reduced I² to 52%. We suggest that differences in relative effects on smoking cessation at the time of surgery may be in part attributable to the intensity of the support given, and in part to the differing definitions of smoking cessation at the time of surgery. Because the absolute rates for smoking cessation and the definitions used were so varied, we summarise them in Table 2. Excluding two trials (Wolfenden 2005; Andrews 2006) that had no biochemical validation of self‐reported cessation did not substantively change the pooled estimate for brief intervention.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Behavioural intervention versus control, outcome: 1.1 Smoking cessation at time of surgery.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Behavioural intervention versus control, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at time of surgery.

1. Short‐term cessation outcomes.

| Study identifier | Intervention % quit | Control % quit | Abstinence Definition | Validation |

| Brief Intervention | ||||

| Ratner 2004 | 69% | 52% | Abstinent at least 24 hours before surgery | CO |

| Wolfenden 2005 | 78% | 64% | Abstinent at least 24 hours before surgery | None |

| Andrews 2006 | 35% | 16% | No puff on day of surgery | None |

| Sørensen 2007 | 23% | 12% | Continuous abstinence at least 1 month before surgery | Saliva cotinine |

| Thomsen 2010 | 28% | 11% | Continuous abstinence from 2 days before to 10 days after surgery | CO |

| Lee 2013 | 14.3% | 3.6% | Continuous abstinence from smoking for at least 7 days before surgery combined with an exhaled CO ≤ 10ppm | CO |

| Shi 2013 | 79% | 75% | Self‐reported abstinence on the day of surgery | CO |

| Intensive intervention | ||||

| Lindström 2008 | 39% | 2% | Continuous abstinence from at least 3 weeks before surgery to 4 weeks after surgery | CO |

| Møller 2002 | 64% | 7.7% | Continuous abstinence for at least 4 weeks prior to surgery | Weekly CO |

| Ostroff 2013 | 45% | 45% | 24‐hour point prevalence abstinence at hospital admission for surgery | CO |

| Pharmacotherapy | ||||

| Wong 2012 | 29.6% | 20% | 7‐day point‐prevalence abstinence rate at admission to hospital | CO & urinary cotinine |

| Warner 2012 | 73% | 54% | Self‐reported abstinence on the morning of surgery | CO |

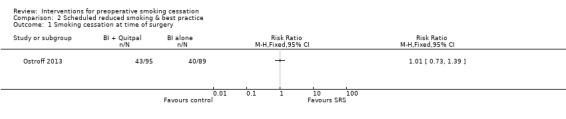

Ostroff 2013 provided both intervention and control participants with an intensive intervention, and was therefore not pooled with other behavioural interventions. This study found equally high cessation rates at surgery in both intervention and control participants (45% in both groups). There was no evidence of additional benefit from the computer‐based reduced smoking regimen given to intervention participants (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.39; 184 participants. Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Scheduled reduced smoking & best practice, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at time of surgery.

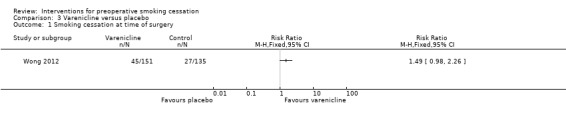

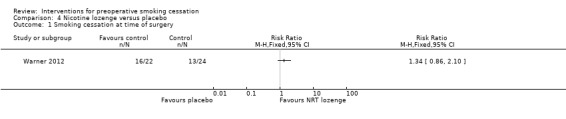

Warner 2012 and Wong 2012 were considered separately as single studies of different pharmacotherapies. The effect of varenicline versus placebo on abstinence on the target quit day, the day before surgery, approached significance; Wong 2012, RR 1.49; 95% CI 0.98 to 2.26; 286 participants, Analysis 3.1), while the effect of nicotine lozenges on abstinence on the morning of surgery was non‐significant; Warner 2012 RR 1.34 (95% CI 0.86 to 2.10; 46 participants. Analysis 4.1)

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Varenicline versus placebo, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at time of surgery.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Nicotine lozenge versus placebo, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at time of surgery.

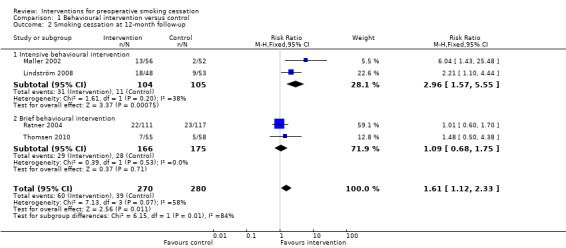

Cessation postoperatively at 12‐month follow up

Only five of the 13 studies monitored longer‐term postoperative cessation, i.e. smoking cessation at 12‐month follow‐up. The two trials of intensive interventions retained significantly higher quit rates in intervention versus control group participants; 23% versus 4% (Møller 2002), and 37% versus 17% (Lindström 2008). The pooled RR was 2.96; 95% CI 1.57 to 5.55 (209 participants) for intensive intervention (Analysis 1.2). Quit rates in the two studies using brief interventions decreased over time and significant differences between intervention and control groups were not maintained at 12 months; 20% versus 20% in Ratner 2004; 12% versus 8% in Thomsen 2010, pooled RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.75 (341 participants. Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Behavioural intervention versus control, Outcome 2 Smoking cessation at 12‐month follow‐up.

Sensitivity analyses excluding Ratner 2004 which had over 20% loss to follow‐up, or excluding two studies that did not biochemically evaluate smoking cessation at 12‐month follow‐up (Lindström 2008; Thomsen 2010), did not substantially affect the subgroup estimates, but left only a small amount of data.

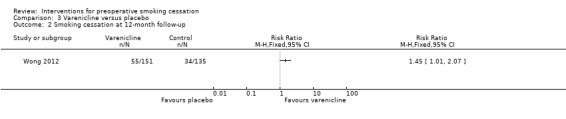

Contrary to the non‐significant effect of varenicline at the time of surgery, Wong 2012 showed a significant increase in smoking cessation at 12 months; RR 1.45; 95% CI 1.01 to 2.07 (286 participants. Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Varenicline versus placebo, Outcome 2 Smoking cessation at 12‐month follow‐up.

Effect on postoperative morbidity and mortality

Any complications

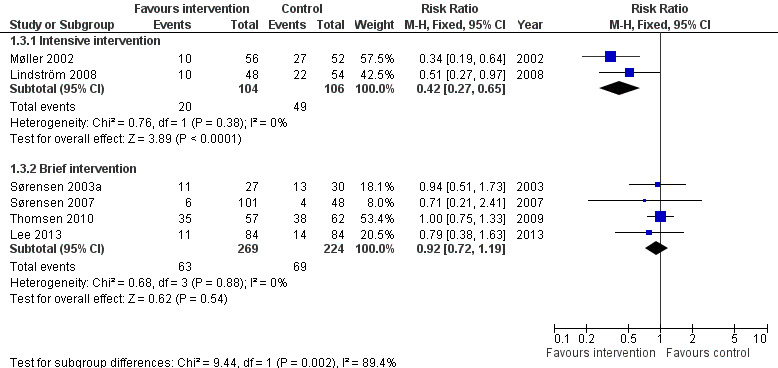

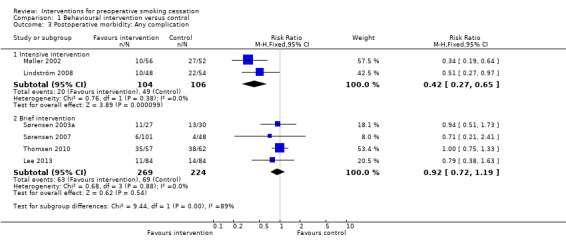

Seven studies reported these outcomes. Two studies, both offering intensive preoperative smoking cessation interventions, found a reduced incidence of postoperative complications. In Møller 2002, 18% intervention versus 52% control participants developed any complication, (P = 0.0003). In Lindström 2008, the corresponding figures were 21% versus 41%, (P = 0.03). None of the four studies offering brief interventions (Sørensen 2003a; Sørensen 2007; Thomsen 2010; Lee 2013) detected significant differences between intervention and control participants in the incidence of postoperative complications. In Sørensen 2003a, 41% intervention versus 43% control participants developed any type of complication, in Thomsen 2010 61% intervention and 61% control participants, and in Lee 2013 13.1% intervention and 16.7% control participants. Lee 2013 monitored intra‐ and postoperative complications. Sørensen 2007 specifically monitored wound infections and did not detect any difference between the intervention and control groups. Pooling intensive and brief interventions separately, the RR for developing any complication was 0.42; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.65 (210 participants) using intensive interventions and 0.92; 95% CI 0.72 to 1.19 (493 participants) for brief interventions (Figure 4; Analysis 1.3). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity in either subgroup.

4.

Behavioural intervention versus control: Postoperative morbidity: Any complication.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Behavioural intervention versus control, Outcome 3 Postoperative morbidity: Any complication.

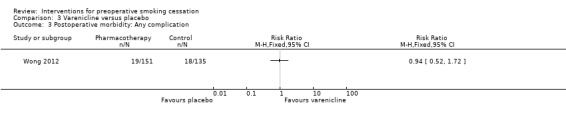

Wong 2012 found no effect of varenicline on postoperative complications; RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.52 to 1.72 (286 participants. Analysis 3.2).

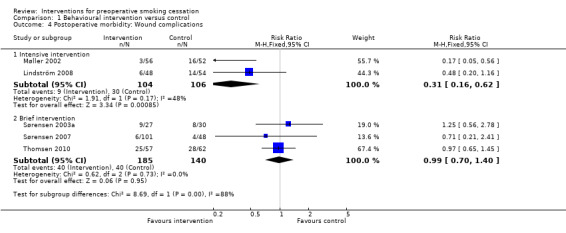

Wound complications

Møller 2002 found a significantly reduced incidence of wound‐related complications in the intervention group (5% versus 31%, P = 0.001). Wound complications were divided into infections (positive culture and antibiotics prescribed), wound haematoma, and wound complication with subfascial involvement. Sørensen 2003a found non‐significant differences in wound‐related complications in 33% of the intervention group and 27% of the control group. In this study wound‐related complications were divided into the following subgroups: anastomotic leakage, fascial dehiscence, wound infection, necrotic stoma, haematoma. Sørensen 2007 monitored wound infections as a secondary outcome and found no significant difference between intervention and control groups in the incidence of these (6% versus 8%). Lindström 2008 likewise found no significant difference between intervention and control groups in the incidence of wound‐related complications (13% versus 26%, P = 0.13). In this study, wound‐related complications were divided into the following sub‐groups: haematoma, wound infection, seroma, other wound complication requiring intervention. Thomsen 2010 found identical incidences of wound‐related complications in intervention and control participants (44% versus 45%). Wound‐related complications were divided into the following subgroups: wound infection, haematoma, seroma, epidermolysis/necrosis requiring intervention.

Pooling studies according to intervention intensity, there was an effect of intensive interventions on wound complications: RR 0.31; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.62 (210 participants) but not for brief interventions: RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.40 (325 participants. Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Behavioural intervention versus control, Outcome 4 Postoperative morbidity: Wound complications.

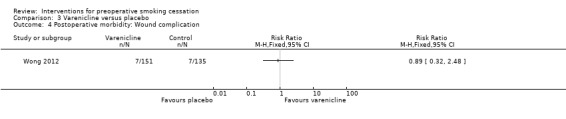

Again, Wong 2012 did not detect any effect of varenicline on wound complications; RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.32 to 2.48 (286 participants. Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Varenicline versus placebo, Outcome 4 Postoperative morbidity: Wound complication.

Other surgical outcomes

Secondary surgery was performed in 4% of the intervention group and in 15% of the control group participants in Møller 2002. In the intervention group, one participant had reposition of the prosthesis, and one had wound‐related secondary surgery. In the control group seven participants (13%) had wound‐related secondary surgery, and one had vascular‐related secondary surgery. Although it is evident that some participants in Sørensen 2003a had secondary surgery, no data on this are given in the paper. Sørensen 2007 and Lindström 2008 did not report data on secondary surgery. Thomsen 2010 found no difference between groups in the need for secondary surgery due to complication; one participant in the intervention group due to haematoma versus no participants in the control group.

Cardiopulmonary complications

No studies detected significant differences between groups in regard to postoperative pulmonary or cardiovascular complications. Møller 2002 found 2% intervention versus 2% control group participants suffering from respiratory insufficiency, and 0% versus 10% suffering from cardiovascular insufficiency, needing either ventilatory support or cardiological treatment. Sørensen 2003a found 11% with pulmonary complications in the intervention group versus 16% in the control group. No cardiac complications were recorded in this study. Lindström 2008 found 0% with pulmonary complications in the intervention group versus 2% in the control group, and 2% with cardiovascular complications in both the intervention and control groups. Thomsen 2010 found 30% with pulmonary complications in the intervention group versus 34% in the control group. Pulmonary complications were all minor, primarily desaturation requiring supplemental oxygen after transfer from the postoperative recovery room. Furthermore, Thomsen 2010 found 3% intervention participants with cardiovascular complications versus 2% control participants. Wong 2012 found no differences between groups in pulmonary complications (0% intervention versus 0.7% control) or in cardiovascular complications (3% intervention versus 1.3% control).

Intensive care admissions

Møller 2002 states the number of days spent in intensive care in the two groups as two days in the intervention group versus 32 days in the control group. The number of participants was not stated.

Length of stay

No studies detected significant differences in duration of hospital admission. Duration of hospital admission was 11 days (range 7 to 55) in the intervention group and 13 (range 8 to 65) in the control group in Møller 2002. Sørensen 2003a found that the median duration of hospital admission was 11 days in both groups (range 8 to 14). Lindström 2008 reported a median duration of hospital admission of one day (range 0 to 10) for the intervention group versus one day for the control group (range 0 to 11). The corresponding numbers in Thomsen 2010 were two days (range one to seven) in the intervention group versus three days (range one to eight) in the control group. Lee 2013 reported 1.75 days (Interquartile Range (IQR) 1.1 to 3.1) in intervention participants versus 2.1 (IQR 1.4 to 3.2) in control participants.

Mortality

There were two deaths in the control group during the perioperative period in Sørensen 2003a. In Ostroff 2013, one intervention participant and two control participants died postoperatively.

Adverse events

No studies reported serious adverse events. Wong 2012 found nausea to be the most common adverse event reported by participants; 13.3% among those receiving varenicline versus 3.7% among those receiving placebo (P = 0.004).

Discussion

Two questions need to be answered in order to investigate the possible prevention of smoking‐related postoperative complications.The first is whether preoperative smoking intervention, behavioural or pharmacological or a combination, reduces smoking by people before surgery. The second is whether successful preoperative smoking cessation reduces the incidence of postoperative complications. This review includes 12 studies addressing the first question, but only seven of them address the second. Of these, two trials offering intensive smoking cessation interventions (Møller 2002; Lindström 2008), one of which (Møller 2002) was conducted by two of the authors of this review, achieved a large change in smoking behaviour in the intervention group, and a lower incidence of complications. Among the remaining eight trials offering brief interventions, four had a modestly significant effect on smoking cessation at the time of surgery (Ratner 2004; Andrews 2006; Thomsen 2010; Lee 2013), and the pooled effect of brief interventions supported an effect on abstinence, but not on postoperative complications. Thomsen 2010 was also conducted by two of the authors of this review. Wong 2012 identified no effect of varenicline initiated one week prior to surgery on smoking cessation at surgery or on postoperative complications. In this study, participants were not asked to quit until the day before surgery. The effect on long‐term cessation was consistent with the results of trials in other populations (Cahill 2012). The difference in effects on complications between intensive and brief interventions may be due to both the intensity and the timing of the intervention. The smoking cessation intervention began six to eight weeks before scheduled surgery in Møller 2002, and in Lindström 2008 it began four weeks before surgery and continued for four weeks postoperatively. In Sørensen 2003a and Lee 2013, participants had access to counselling two to three weeks before surgery; in Sørensen 2007, a brief intervention was provided one month before surgery; and in Thomsen 2010 participants received a brief intervention shortly before surgery. This suggests that intensive counselling, and in parallel with this a longer period of preoperative varenicline are needed to support and sustain smoking cessation; furthermore, a longer period of abstinence may be required to achieve a reduction in some or all types of complication. Based on indirect comparisons, the effects of brief interventions are likely to be smaller than those of more intensive ones. Although we detected no significant effects on postoperative complications or long‐term cessation, the confidence intervals do not exclude small effects of brief interventions on these outcomes. The comparisons between intensity subgroups were initially exploratory, but the increased number of studies strengthens our confidence in a difference in effect attributable to timing and duration of support..

Pathophysiologically, smoking‐induced reduction in lung function may be significantly improved by six to eight weeks of smoking abstinence (Buist 1976). The smoking‐related impairment of immune function may likewise be reversed by six to eight weeks of abstinence (Beckers 1991; Akrawi 1997). These studies suggest that smoking cessation interventions are likely to be more beneficial when offered at least six weeks before surgery than in the immediate preoperative period, if possible. This complements the results of this review. Intensive intervention for four to eight weeks preoperatively, including provision of NRT, supported smoking cessation and reduced postoperative complications. Rigotti 2012 concluded similarly in a review of the effect of interventions on smoking cessation in hospitalized patients. Such interventions may, however, be difficult to achieve unless there is a partnership between surgical services and other branches of the health service, particularly primary care.

The interventions were tested in heterogeneous surgical populations which increases the external validity of the review. However, different surgical procedures and underlying pathologies may have diverse impacts on the incidence of postoperative complications and on motivation for and ability to stop smoking. This might have influenced the type of complications likely to occur as well as smoking cessation rates. Ostroff 2013, for example, found that participants with thoracic cancers were more likely to quit smoking than those with other cancer sites.

Overall, the studies were assessed to be at low risk of bias. However, assessment of postoperative complications may have been subject to intra‐ and interobserver variation (Bruce 2001). Self report of smoking cessation by participants without biochemical validation may similarly introduce a risk of performance and detection bias, given the lack of blinding (Higgins 2011). Differences between studies in definitions of postoperative complications and smoking cessation, specifically smoking cessation at the time of surgery, may be a potential source of heterogeneity affecting the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn. Interventions were furthermore primarily provided by research nurses or assistants specifically allocated to this task. This raises the question of whether intervention effects will persist when administered by staff within routine clinical settings.

The studies were conducted between 2002 and 2013. Within this time frame, attitudes to smoking have changed and many countries, and hence hospitals, have implemented restrictive smoking policies, including those from which the studies originate. This may have influenced control interventions in the more recent studies, with control participants receiving brief cessation advice and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) ( Wolfenden 2005; Sørensen 2007; Thomsen 2010; Wong 2012; Warner 2012). This could potentially have rendered the relative additional effect of brief interventions smaller, thus making detection of any incremental benefit more difficult. In Ostroff 2013, quit rates were high in both groups, probably because both groups received intensive intervention, the only difference being the scheduled reduced smoking (SRS) in the intervention group. Detection of any incremental effect of the SRS was therefore likely to be difficult. Small sample sizes may further aggravate the detection of smaller but potentially clinically important, intervention effects. The small sample sizes and the relatively small number of studies contributing data to the meta‐analyses contribute to a judgement that the overall quality of evidence is moderate rather than high.

The validity of using composite outcomes to assess the effect of smoking intervention on postoperative morbidity is also debatable (Montori 2005). Two studies (Møller 2002; Lindström 2008) identified a significant effect on composite outcomes for postoperative complications and wound complications. When assessing intervention effects, careful consideration should be given to those complications comprising the composite outcomes that are of clinical significance and greatest importance to patients (Montori 2005).

The results support the view that interventions that help people to stop smoking in other settings also work for perioperative patients. These include measures to increase motivation and treat nicotine dependence, and intensive behavioural support (Rigotti 2012), NRT (Stead 2012) and varenicline (Cahill 2012).

Whether the perioperative period is a particularly suitable time for smoking interventions, however, warrants further investigation. Schwartz 1987 demonstrated that people may be more likely to comply with smoking cessation advice during the time of an acute illness. Ostroff 2013 found that participants with thoracic cancers were more likely to quit smoking than those with other cancer sites. Recently Shi 2010 reported an association between undergoing surgery and an increased likelihood for smoking cessation in older US citizens, with a particularly marked association in those undergoing major surgery. Participants reported that the possibility of reducing perceived vulnerability to postoperative complications promoted motivation to quit or reduce smoking prior to operation (Møller 2004; Thomsen 2009). Lindström 2010 found that participants randomized to the control intervention were disappointed with this allocation. On the other hand, some smokers found it more difficult to quit when facing the stress of an operation (Møller 2004; Thomsen 2009). Two studies recruited substantially fewer participants than planned (Sørensen 2003a; Lindström 2008), and Thomsen 2010 recruited only 51% of eligible patients. This may reflect a lack of motivation among some smokers to stop smoking in relation to surgery.

None of the studies included in this review reported serious adverse effects of preoperative smoking intervention, supporting the safety of short‐term preoperative smoking cessation. This is consistent with a recent meta‐analysis that found no adverse effects on surgical outcomes of stopping smoking shortly before surgery (Myers 2011). It has previously been claimed that recent quitters may suffer from pulmonary symptoms such as cough and sputum production.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Intensive interventions initiated at least four weeks before surgery and including multiple contacts for behavioural support and the offer of pharmacotherapy are beneficial for changing smoking behaviour perioperatively and in the long term, and for reducing the incidence of complications. Brief interventions offered closer to the time of surgery are likely to have a small benefit on smoking behaviour, but have not been demonstrated to reduce complications. The current evidence supports giving smokers scheduled for surgery advice to quit and offering them effective interventions, including behavioural support and pharmacotherapy, at least four weeks ahead of surgery if possible.

Implications for research.

We need to establish the effect on postoperative morbidity and smoking cessation of interventions that are initiated immediately before or after surgery, for example subacute and acute surgery, and continued for at least eight weeks. The effect on postoperative complications of intensive interventions before higher morbidity surgical procedures, for example upper abdominal and thoracic surgery, also needs to be established. We also need to know how preoperative smoking intervention affects long‐term smoking abstinence rates, so future studies should include at least 12‐month follow‐up. In addition we need to evaluate the effect of different methods of smoking intervention, including other pharmacotherapies than NRT (Hughes 2014; Cahill 2012) in order to find the most effective way of supporting smoking cessation in people undergoing surgery. Varenicline may have potential as an intervention for smoking cessation in relation to surgery but more trials are needed in this population. Finally, the perspectives of smokers who decline to participate in perioperative smoking cessation trials warrant research.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 January 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No major change to conclusions, stronger evidence about brief behavioural interventions, two new trials evaluating pharmacotherapy. |

| 30 January 2014 | New search has been performed | Searches updated; 5 new included studies. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2000 Review first published: Issue 2, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 July 2010 | Amended | Minor edits including change to abstract; 5 trials (rather than 6) detected significantly increased smoking cessation at the time of surgery. |

| 18 May 2010 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Updated for Issue 7, 2010 with 4 new trials and clearer evidence on short‐term outcomes. Change to authorship. |

| 3 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 17 May 2005 | New citation required and minor changes | Four new trials included. |

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Tom Pedersen who was an author on the first version of this review, and to the Managing Editor/Trial Search Co‐ordinator Lindsay Stead, Tobacco Addiction Group, for invaluable help with literature search.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Specialized Register search strategy

Register search strategy using Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS)

#1 (pre?operative or post?operative):TI,AB,MH,EMT,XKY,KY,KW #2 (surgery or operation? or operative or an?esthesia):TI,MH,EMT,KY,KW #3 (surgery or operation? or operative or an?esthesia):XKY #4 #1 or #2 OR #3

MH, EMT, KY & KW are keyword fields from electronic database records. XKY includes keywords assigned as part of internal indexing

Appendix 2. MEDLINE, EMBASE & CINAHL search strategies

These strategies were last run in April 2010

MEDLINE STRATEGY (via OVIDSP)

1. RANDOMIZED‐CONTROLLED‐TRIAL.pt. 2. CONTROLLED‐CLINICAL‐TRIAL.pt. 3. CLINICAL‐TRIAL.pt. 4. exp Clinical Trial/ 5. Random‐Allocation/ 6. randomized‐controlled trials/ 7. smoking cessation.mp. or exp Smoking Cessation/ 8. "Tobacco‐Use‐Cessation"/ 9. "Tobacco‐Use‐Disorder"/ 10. exp Smoking/pc, th [Prevention & Control, Therapy] 11. (surgery or operation or operativ: or an?esthesia).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier] 12. exp Postoperative complication/ 13. exp Preoperative care/ 14. exp Patient education/ 15. 12 and (13 or 14) 16. 11 or 15 [topic related terms] 17. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 [design terms] 18. 8 or 7 or 9 or 10 [smoking terms] 19. 16 and 17 and 18

EMBASE STRATEGY (via OVIDSP)

1. smoking cessation.mp. or Smoking Cessation/ 2. smoking/ 3. ((smok* or tobacco or cigar*) adj3 (stop* or quit* or giv* or refrain* or reduc*)).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier] 4. 1 or (2 and 3) 5. (surgery or surgical or operation or operativ* or preoperativ* or an?esthesia).ti,an,de. 6. 4 and 5

CINAHL STRATEGY

1. "Smoking‐Cessation" OR "Smoking‐Cessation‐Programs" OR "Smoking"/ prevention‐and‐control OR (smoking cessation) OR ((smok* or tobacco or cigar*) near (stop* or quit*)) 2. surgery or operation or operativ* or an?esthesia 3. #1 AND #2

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Behavioural intervention versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at time of surgery | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Intensive behavioural intervention | 2 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 10.76 [4.55, 25.46] |

| 1.2 Brief behavioural intervention | 7 | 1141 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [1.16, 1.46] |

| 2 Smoking cessation at 12‐month follow‐up | 4 | 550 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.61 [1.12, 2.33] |

| 2.1 Intensive behavioural intervention | 2 | 209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.96 [1.57, 5.55] |

| 2.2 Brief behavioural intervention | 2 | 341 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.68, 1.75] |

| 3 Postoperative morbidity: Any complication | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Intensive intervention | 2 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.27, 0.65] |

| 3.2 Brief intervention | 4 | 493 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.72, 1.19] |

| 4 Postoperative morbidity: Wound complications | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Intensive intervention | 2 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.16, 0.62] |

| 4.2 Brief intervention | 3 | 325 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.70, 1.40] |

Comparison 2. Scheduled reduced smoking & best practice.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at time of surgery | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 3. Varenicline versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at time of surgery | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Smoking cessation at 12‐month follow‐up | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Postoperative morbidity: Any complication | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Postoperative morbidity: Wound complication | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Varenicline versus placebo, Outcome 3 Postoperative morbidity: Any complication.

Comparison 4. Nicotine lozenge versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at time of surgery | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Andrews 2006.

| Methods | Country: United Kingdom Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | 102 smoking participants (51 intervention, 51 control) routinely attending the preoperative ward 4 weeks before surgery. The types of surgery were not specified. | |

| Interventions | Intervention: In addition to booklet and nurse advice given to all participants when they are routinely seen 4 weeks prior to surgery, intervention group participants received a letter from the participant's consultant stating that stopping smoking 1 ‐ 2 weeks before surgery has huge benefits. Participants were furthermore provided with contact details for Stop Smoking Service. Control: Booklet and nurse advice. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported abstinence from smoking, defined as not smoking a single puff on the day of surgery. No biochemical conformation of smoking status. | |

| Notes | Smoking cessation defined as point prevalence. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Numbers drawn from opaque bag |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Each patient agreeing to participate on the pre‐operative ward that day was numbered sequentially. The corresponding numbers were put in an opaque bag and the first number drawn out was assigned to intervention status." Although this system is open to manipulation we did not judge the risk of bias to be high in this study. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of participants or personnel, assessors of smoking status not stated as blinded, |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All intervention group participants completed, 1/51 missing from control group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes as prespecified in the article are reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Lee 2013.

| Methods | Country: Canada Randomized controlled trial |

|

| Participants | 168 daily smokers (84 intervention/84 control) scheduled for elective surgery and having a preadmission clinic appointment at least 3 weeks before their surgical date. The primary types of surgery were general surgery, gynaecologic, urologic, ophthalmologic, otolaryngologic and orthopaedic. | |

| Interventions | Intervention: 5‐minute counselling by a trained preadmission nurse, brochures on smoking cessation, referral to the Canadian Cancer Society's Smokers' Helpline. The Smoker's Helpline initiated contact with participants (up to 4 attempts) and subsequent counselling was agreed on with the participant, generally aiming at having at least 4 contacts with each person. 6‐week supply of free transdermal nicotine replacement. Control: Standard care implying inconsistent smoking cessation advice from nurses, surgeons or anaesthesiologists. |

|

| Outcomes | Self‐reported abstinence from smoking for at least 7 days before surgery combined with an exhaled CO ≤ 10 ppm. Inaccurately reported preoperative smoking cessation (self‐reported 7‐day abstinence with exhaled CO > 10 ppm). A composite of all intraoperative and immediate postoperative complications (those occurring in PACU) Total duration of care in PACU and time to PACU discharge readiness. Unanticipated hospital admission (participants scheduled for day surgery and subsequently admitted to hospital). Hospital length of stay for inpatients. Self‐reported smoking cessation for 7 days before the 30‐day postoperative phone call. Self‐reported smoking reduction (by ≥ 50% of baseline) at the 30‐day postoperative phone call. |

|

| Notes | Smoking cessation only as 7‐day point prevalence. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated block randomization. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Opaque sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment. Participants not blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 5 intervention and 6 control participants lost to follow‐up. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Lindström 2008.

| Methods | Country: Sweden Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | 117 daily smokers undergoing elective surgery for primary hernia repair, laparoscopic cholecystectomy and hip or knee prosthesis. | |

| Interventions | Intervention: weekly sessions, face‐to‐face or by telephone, with a trained smoking cessation counsellor and NRT 4 weeks pre‐ and 4 weeks postoperatively. Control: Standard care. | |

| Outcomes | Smoking cessation from 3 weeks before to 4 weeks after surgery, and at 1 year (not validated). Postoperative complications requiring intervention within 30 days postoperatively. Wound complications requiring intervention within 30 days postoperatively. |

|

| Notes | Smoking cessation was validated by CO in exhaled air. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Stratified block randomization. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Opaque sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Outcomes assessed by study nurses who were not blinded and by the study physicians who were unaware of group allocation. No blinding of participants or personnel. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to 30‐day follow‐up. 7/48 intervention and 3/54 controls lost to 12‐month follow‐up. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Reports all prespecified outcomes. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Møller 2002.

| Methods | Country: Denmark Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | 120 daily smokers (60 intervention, 60 control) who underwent elective hip or knee replacement surgery. | |

| Interventions | Intervention: Weekly meetings initiated 6 ‐ 8 weeks prior to surgery. Personalized nicotine substitution schedule. Participants were strongly encouraged to stop smoking but also had the option to reduce tobacco consumption by at least 50%. Advice about smoking cessation/reduction, benefits, side effects, how to manage withdrawal symptoms, and how to keep weight gain to a minimum. Participants could also discuss other issues related to smoking intervention or hospitalization. The intervention was provided by a research nurse trained as a smoking cessation counsellor. Control: Standard care, which was little or no information about the risks of tobacco smoking or smoking cessation counselling. | |

| Outcomes | Smoking cessation before surgery, 4 weeks after surgery and 1 year after surgery. Outcome assessor blinded. Long‐term smoking cessation was validated in those who participated in focus group interviews by measurements of CO in exhaled air. | |

| Notes | Randomized participants who did not have surgery are not included in denominators; Long‐term cessation is reported in Villebro 2008 and included in the text and analyses under this study identifier. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Stratified block randomization. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Opaque sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment. No blinding of participants or personnel. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 4/60 intervention participants and 8/60 control participants missing due to cancellation of surgery; 0/56 intervention and 11/52 controls were missing at 1‐year follow‐up. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes as prespecified in the article are reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Reports all prespecified outcomes. |

Ostroff 2013.

| Methods | Country: USA Randomized controlled trial |

|

| Participants | 185 smokers (minimum 8 CPD within the past week) with newly diagnosed cancer who were scheduled for hospitalization and surgical resection no less than 7 days from study entry, with sufficient visual acuity and manual dexterity to use a handheld computer. Cancer sites included thoracic, head and neck, breast, gynaecology, urology, other. | |

| Interventions | Intervention: Best Practice (BP) and Scheduled Reduced Smoking (SRS).

BP = 5 individual counselling sessions with trained smoking cessation counsellors and nicotine replacement therapy at no cost. 2 sessions prior to surgery, 1 during hospitalization, 2 sessions during the month after hospital discharge. Apart from the 3rd session during hospitalization, counselling was provided by telephone.

SRS = individually tailored presurgical gradual tapering regimen prompted by QuitPal. A quit date was planned at least 24 hours prior to hospital admission. Control: BP as described above |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at hospital admission verified by exhaled CO. Also reported; Primary: 7‐day point prevalence abstinence at 6 months post‐hospitalization verified by saliva cotinine. Secondary: abstinence at 3 months post‐hospitalization verified by saliva cotinine, cigarettes smoked per day at the same follow‐up times. |

|