Abstract

Background

Castor oil, a potent cathartic, is derived from the bean of the castor plant. Anecdotal reports, which date back to ancient Egypt have suggested the use of castor oil to stimulate labour. Castor oil has been widely used as a traditional method of initiating labour in midwifery practice. Its role in the initiation of labour is poorly understood and data examining its efficacy within a clinical trial are limited. This is one of a series of reviews of methods of cervical ripening and labour induction using standardised methodology.

Objectives

To determine the effects of castor oil or enemas for third trimester cervical ripening or induction of labour in comparison with other methods of cervical ripening or induction of labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (30 April 2013) and bibliographies of relevant papers.

Selection criteria

Clinical trials comparing castor oil, bath or enemas used for third trimester cervical ripening or labour induction with placebo/no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of labour induction methods.

Data collection and analysis

A strategy was developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. This involved a two‐stage method of data extraction.

Main results

Three trials, involving 233 women, are included. There was no evidence of differences in caesarean section rates between the two interventions in the two trials reporting this outcome (risk ratio (RR) 2.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.92 to 4.55). There were no data presented on neonatal or maternal mortality or morbidity.

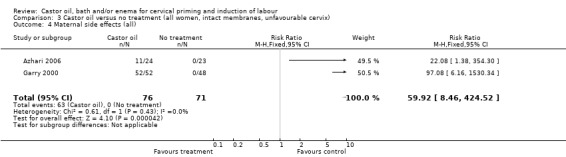

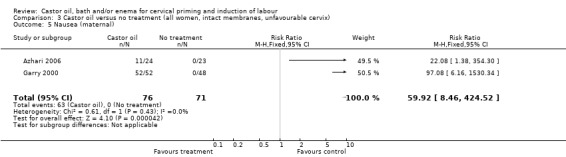

There was no evidence of a difference between castor oil and placebo/no treatment for the rate of instrumental delivery, meconium‐stained liquor, or Apgar score less than seven at five minutes. The number of participants was too small to detect all but large differences in outcome. All women who ingested castor oil felt nauseous (RR 59.92, 95% CI 8.46 to 424.52).

Authors' conclusions

The three trials included in the review contain small numbers of women. All three studies used single doses of castor oil. The results from these studies should be interpreted with caution due to the risk of bias introduced due to poor methodological quality. Further research is needed to attempt to quantify the efficacy of castor oil as an cervical priming and induction agent.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Castor Oil; Castor Oil/administration & dosage; Castor Oil/adverse effects; Cervical Ripening; Enema; Oxytocics; Oxytocics/administration & dosage; Oxytocics/adverse effects; Cesarean Section; Cesarean Section/statistics & numerical data; Labor, Induced; Labor, Induced/methods; Pregnancy Trimester, Third; Prostaglandins; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Castor oil, bath and/or enema for cervical priming and induction of labour

Sometimes it is necessary to bring on labour artificially. Castor oil has been widely used as a traditional method of inducing labour in midwifery practice. It can be taken by mouth or as an enema. The review of three trials, involving 233 women, found there has not been enough research done to show the effects of castor oil on ripening the cervix or inducing labour or compare it to other methods of induction. The review found that all women who took castor oil by mouth felt nauseous. More research is needed into the effects of castor oil to induce labour.

Background

Sometimes it is necessary to bring on labour artificially because of safety concerns for the mother or baby. This review is one of a series of reviews of methods of labour induction using a standardised protocol. For more detailed information on the rationale for this methodological approach, please refer to the currently published 'generic' protocol (Hofmeyr 2009). The generic protocol describes how a number of standardised reviews will be combined to compare various methods of preparing the cervix of the uterus and inducing labour.

Castor oil, a potent cathartic, is derived from the bean of the castor plant. Anecdotal reports, which date back to ancient Egypt have suggested the use of castor oil to stimulate labour.

Castor oil has been widely used as a traditional method of initiating labour in midwifery practice. Its role in the initiation of labour is poorly understood and data examining its efficacy within a clinical trial are limited.

Objectives

To determine the effects of castor oil or enemas for third trimester cervical ripening or induction of labour in comparison with other methods of cervical ripening or induction of labour.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing the use of castor oil or baths and/or enemas for cervical ripening or labour induction, with placebo/no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction (see Types of interventions); the trials included some form of random allocation to either group; and they reported one or more of the pre‐stated outcomes.

Types of participants

Pregnant women due for third trimester induction of labour, carrying a viable fetus.

Types of interventions

Clinical trials comparing castor oil or enemas for cervical ripening or labour induction with placebo/no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction (see list below).

To avoid duplication of data in a series of reviews on interventions for labour induction as described in the generic protocol for methods for cervical ripening and labour induction in late pregnancy (Hofmeyr 2009), the labour induction methods were listed in a specific order, from one to 27. Each review included comparisons between one of the methods (from two to 27) with only those methods above it on the list. Thus, this review of castor oil, bath, and/or enema (19) could include comparisons with any of the following: (1) placebo/no treatment; (2) vaginal prostaglandins; (3) intracervical prostaglandins; (4) intravenous oxytocin; (5) amniotomy; (6) intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy; (7) vaginal misoprostol; (8) oral misoprostol; (9) mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter; (10) membrane sweeping; (11) extra‐amniotic prostaglandins; (12) intravenous prostaglandins; (13) oral prostaglandins; (14) mifepristone; (15) oestrogens with or without amniotomy; (16) corticosteroids; (17) relaxin; or (18) hyaluronidase. Methods identified in the future will be added to the end of the list. The current list is as follows:

(1) placebo/no treatment; (2) vaginal prostaglandins (Kelly 2009); (3) intracervical prostaglandins (Boulvain 2008); (4) intravenous oxytocin (Alfirevic 2009); (5) amniotomy (Bricker 2000); (6) intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy (Howarth 2001); (7) vaginal misoprostol (Hofmeyr 2010); (8) oral misoprostol (Alfirevic 2006); (9) mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter (Jozwiak 2012); (10) membrane sweeping (Boulvain 2005); (11) extra‐amniotic prostaglandins (Hutton 2001); (12) intravenous prostaglandins (Luckas 2000); (13) oral prostaglandins (French 2001); (14) mifepristone (Hapangama 2009); (15) oestrogens with or without amniotomy (Thomas 2001); (16) corticosteroids (Kavanagh 2006); (17) relaxin (Kelly 2001); (18) hyaluronidase (Kavanagh 2006a); (19) castor oil, bath, and/or enema (this review); (20) acupuncture (Smith 2004); (21) breast stimulation (Kavanagh 2005); (22) sexual intercourse (Kavanagh 2001); (23) homoeopathic methods (Smith 2003); (24) nitric oxide (Kelly 2011); (25) buccal or sublingual misoprostol (Muzonzini 2004); (26) hypnosis; (27) other methods for induction of labour.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Two authors of labour induction reviews (Justus Hofmeyr and Zarko Alfirevic) prespecified clinically relevant outcomes for trials of methods of cervical ripening/labour induction. They resolved differences by discussion.

Five primary outcomes were chosen as being most representative of the clinically important measures of effectiveness and complications: (1) vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours (or period specified by trial authors); (2) uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes; (3) caesarean section; (4) serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (e.g. seizures, birth asphyxia defined by trialists, neonatal encephalopathy, disability in childhood); (5) serious maternal morbidity or death (e.g. uterine rupture, admission to intensive care unit, septicaemia).

Perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality are composite outcomes. This is not an ideal solution because some components are clearly less severe than others. It is possible for one intervention to cause more deaths but less severe morbidity. However, in the context of labour induction at term this is unlikely. All these events will be rare, and a modest change in their incidence will be easier to detect if composite outcomes are presented. The incidence of individual components are explored as secondary outcomes (see below).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes relate to measures of effectiveness, complications and satisfaction.

Measures of effectiveness

(6) Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 to 24 hours; (7) oxytocin augmentation.

Complications

(8) Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes; (9) uterine rupture; (10) epidural analgesia; (11) instrumental vaginal delivery; (12) meconium‐stained liquor; (13) Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; (14) neonatal intensive care unit admission; (15) neonatal encephalopathy; (16) perinatal death; (17) disability in childhood; (18) maternal side effects (all); (19) maternal nausea; (20) maternal vomiting; (21) maternal diarrhoea; (22) other maternal side‐effects; (23) postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by the trial authors); (24) serious maternal complications (e.g. intensive care unit admission, septicaemia but excluding uterine rupture); (25) maternal death.

Measures of satisfaction

(26) Woman not satisfied; (27) caregiver not satisfied.

'Uterine rupture' includes all clinically significant ruptures of unscarred or scarred uteri. Trivial scar dehiscence noted incidentally at the time of surgery is excluded.

Additional outcomes may appear in individual reviews.

While all the above outcomes were sought, only those with data appear in the analysis tables.

The terminology of uterine hyperstimulation is problematic (Curtis 1987). In the reviews we will use the term 'uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes' to include uterine tachysystole (more than five contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes) and uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting at least two minutes) and 'uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes' to denote uterine hyperstimulation syndrome (tachysystole or hypersystole with fetal heart rate changes such as persistent decelerations, tachycardia or decreased short‐term variability). However, due to varied reporting there is the possibility of subjective bias in the interpretation of these outcomes. Also, it is not always clear from trials if these outcomes are reported in a mutually exclusive manner.

Outcomes were included in the analysis: if reasonable measures were taken to minimise observer bias; and data were available for analysis according to original allocation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (30 April 2013).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

The original search was performed simultaneously for all reviews of methods of inducing labour, as outlined in the generic protocol for these reviews (Hofmeyr 2000).

We searched reference lists of retrieved trial reports.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, see Appendix 1. These methods followed those described in the generic protocol (Hofmeyr 2009), which was developed in order to provide a standardised methodological approach for conducting a series of reviews examining the various methods of preparing the cervix of the uterus and inducing labour.

For this update, the following methods were used for assessing the six reports that were identified as a result of the updated search.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We have assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We have assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We have assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We have assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We have assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We have assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

No continuous data were analysed in this update (2013). In future updates, if continuous data are analysed, we will use the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

No cluster‐randomised trials were found for inclusion in the 2013 update of this review.

In future updates, we will include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook [Section 16.3.4 or 16.3.6] using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials were not eligible for inclusion in this review.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, levels of attrition were noted. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect will be explored by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I² was greater than 30% and either the T² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar.

In future updates, If there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity is detected, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary will be treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials. If we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In future updates, if we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We plan to carry out the following subgroup analyses:

previous caesarean section or not;

nulliparity or multiparity;

membranes intact or ruptured;

cervix favourable, unfavourable or undefined.

Subgroup analyses will be restricted to the review's primary outcomes.

We will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2011). We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the χ2 statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We plan to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor quality studies being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this makes any difference to the overall result.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Nine trials were identified for consideration for inclusion in the review: three were included, five were excluded and one is awaiting further assessment. The included trials contained 233 women in total.

Included studies

Three studies were included: Garry 2000 and Azhari 2006 compared the use of a single dose of castor oil with no treatment in women with intact membranes and unfavourable cervices. Gilad 2012 compared a single dose of castor oil with a placebo in women with an unfavourable cervix.

Excluded studies

Two studies did not report any of the prespecified outcomes and hence were excluded. Mathie 1959 examined the effect of castor oil, soap enema or a hot bath in combination or alone and Saberi 2008 examined the effect of castor oil in comparison with no treatment.

One study examined the effect of castor oil, soap enema and hot bath but these were examined in combination with amniotomy and oxytocin (Nabors 1958). As this is a complex intervention, it is not included in this review.

One study, Azharkish 2008, did not have an English translation available and hence was excluded. A further study, Wang 1997 was translated into English and then was found to be comparing vaginal misoprostol to a complex intervention of fried egg yolks cooked in oil followed by intravenous oxytocin 12 hours later.

Risk of bias in included studies

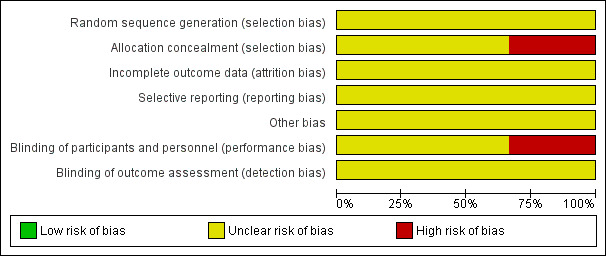

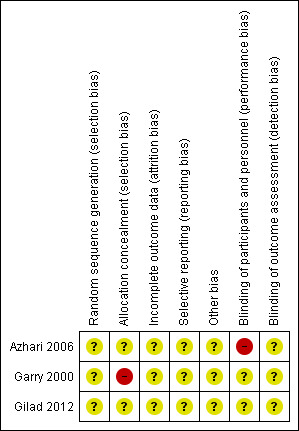

See Figure 1; Figure 2 for a summary of risk of bias assessments in included studies.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

The method of allocation in the included trial (Garry 2000) was by alternation; this may introduce subjective selection bias. In the remaining two trials there were no specific details regarding sequence generation or allocation concealment. Furthermore, no attempt was made to introduce a placebo arm into two trials and hence there was inadequate blinding of both the patient and outcome assessor; this again may have introduced bias into the results. There were no losses to follow‐up in any study.

Effects of interventions

Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (three trials n = 233 eligible, 227 women randomised)

Primary outcomes

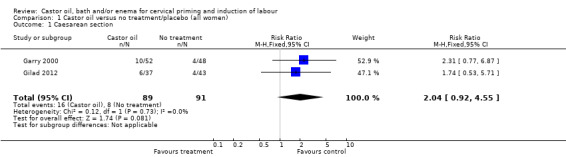

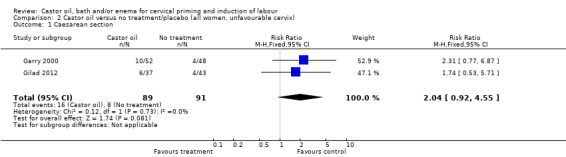

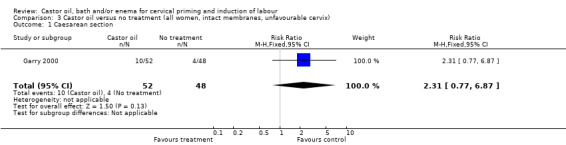

There was no evidence of differences in caesarean section rates between the two interventions in the two trials reporting this outcome (risk ratio (RR) 2.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.92 to 4.55), (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women), Outcome 1 Caesarean section.

There were no other data presented on neonatal or maternal mortality or morbidity.

Secondary outcomes

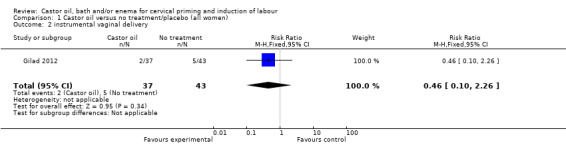

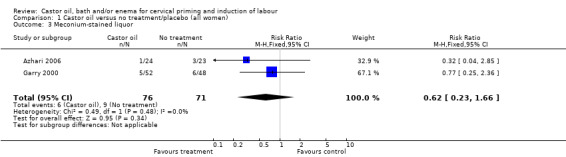

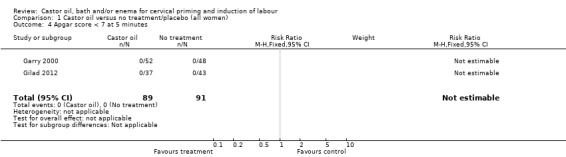

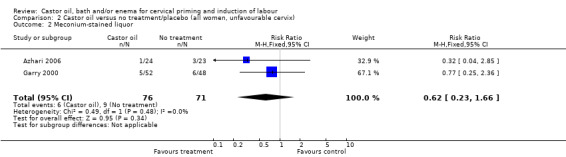

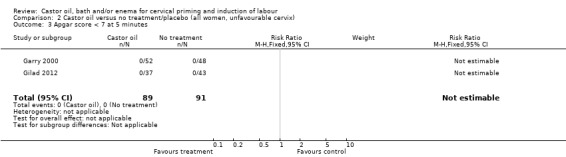

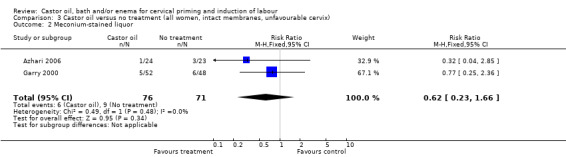

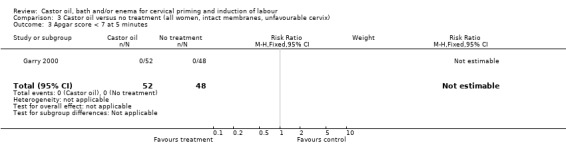

There was no evidence of a difference between castor oil and placebo/no treatment for the rate of instrumental delivery (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.10 to 2.26), (Analysis 1.2); meconium‐stained liquor (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.66), (Analysis 1.3); or Apgar score less than seven at five minutes (no events in any of the studies). The number of participants was too small to detect all but large differences in outcome.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women), Outcome 2 instrumental vaginal delivery.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women), Outcome 3 Meconium‐stained liquor.

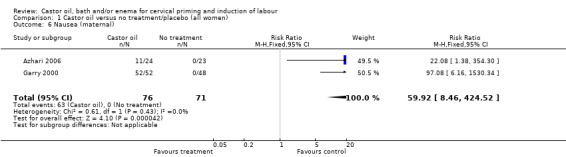

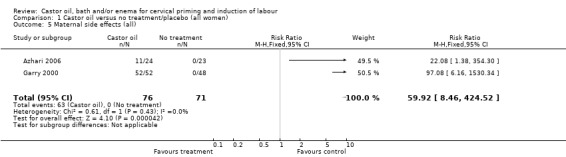

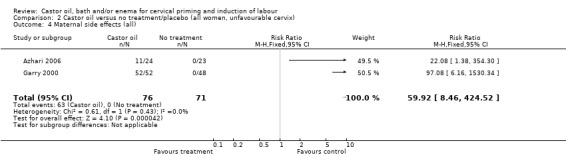

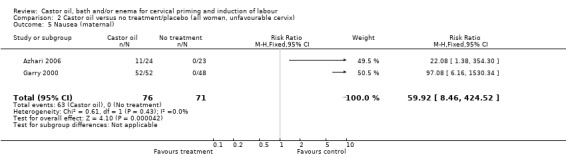

All women who ingested castor oil felt nauseous (RR 59.92, 95% CI 8.46 to 424.52), (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women), Outcome 6 Nausea (maternal).

There was no evidence of significant differences for any reported outcomes (with the exception of nausea) in the all women group. The included studies looked at women with intact membranes and two included women with intact membranes and an unfavourable cervix, hence, although data from predefined subgroups as outlined above are presented, they do not differ from the all women group.

Discussion

The three trials included in the review contain small numbers of women. All three studies used single doses of castor oil. One trial used alternation as a method of allocation, although the other two studies were unclear on the methods used to allocate women. Hence the results from all these studies should be interpreted with caution due to the risk of bias introduced due to poor methodological quality. The incidence of maternal side effects was high in association with castor oil ingestion. Further research is needed to attempt to quantify the efficacy of castor oil as a cervical priming and induction agent.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is still insufficient evidence to make any conclusions regarding the effectiveness of castor oil, bath or enemas as induction agents.

Implications for research.

Future trials examining the effect of castor oil or enemas as induction agents should aim to be of sufficient power to detect a meaningful reduction in clinically relevant outcomes. Future trials should aim to be of high methodological quality.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 June 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Two new trials were included (Azhari 2006; Gilad 2012), three were excluded (Azharkish 2008; Saberi 2008; Wang 1997) and one is awaiting further classification (Porat 2006). |

| 30 April 2013 | New search has been performed | Search updated on 30 April 2013. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2000 Review first published: Issue 2, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 February 2012 | Amended | Search updated. Six reports added to Studies awaiting classification (Azharkish 2008; Azhari 2006; Gilad 2012; Porat 2006; Saberi 2008; Wang 1997). |

| 4 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jim Neilson, Zarko Alfirevic and Justus Hofmeyr for their advice and patience during the development of this review and Caroline Crowther for her patience and attention to detail during the final production of the review.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods used in previous versions of this review

A strategy was developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. Many methods have been studied, examining the effects of these methods when induction of labour was undertaken in a variety of clinical groups e.g. restricted to primiparous women or those with ruptured membranes. Most trials are intervention‐driven, comparing two or more methods in various categories of women. Clinicians and parents need the data arranged according to the clinical characteristics of the women undergoing induction of labour, to be able to choose which method is best for a particular clinical scenario. To extract these data from several hundred trial reports in a single step would be very difficult. We therefore developed a two‐stage method of data extraction. The initial data extraction was done in a series of primary reviews arranged by methods of induction of labour, following a standardised methodology. The intention was then to extract them from the primary reviews into a series of secondary reviews, arranged by the clinical characteristics of the women undergoing induction of labour.

To avoid duplication of data in the primary reviews, the labour induction methods were listed in a specific order, from one to 25. Each primary review included comparisons between one of the methods (from two to 25) with only those methods above it on the list. Thus, the review of intravenous oxytocin (4) included only comparisons with intracervical prostaglandins (3), vaginal prostaglandins (2) or placebo (1). Methods identified in the future will be added to the end of the list. The current list is as follows:

(1) placebo/no treatment; (2) vaginal prostaglandins (Kelly 2009); (3) intracervical prostaglandins (Boulvain 2008); (4) intravenous oxytocin (Alfirevic 2009); (5) amniotomy (Bricker 2000); (6) intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy (Howarth 2001); (7) vaginal misoprostol (Hofmeyr 2010); (8) oral misoprostol (Alfirevic 2006); (9) mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter (Boulvain 2001); (10) membrane sweeping (Boulvain 2005); (11) extra‐amniotic prostaglandins (Hutton 2001); (12) intravenous prostaglandins (Luckas 2000); (13) oral prostaglandins (French 2001); (14) mifepristone (Hapangama 2009); (15) oestrogens with or without amniotomy (Thomas 2001); (16) corticosteroids (Kavanagh 2006); (17) relaxin (Kelly 2001); (18) hyaluronidase (Kavanagh 2006a); (19) castor oil, bath, and/or enema; (20) acupuncture (Smith 2004); (21) breast stimulation (Kavanagh 2005); (22) sexual intercourse (Kavanagh 2001); (23) homoeopathic methods (Smith 2003); (24) nitric oxide (Kelly 2011); (25) buccal or sublingual misoprostol (Muzonzini 2004); (26) other methods for induction of labour.

The primary reviews were analysed by the following subgroups: (1) previous caesarean section or not; (2) nulliparity or multiparity; (3) membranes intact or ruptured; (4) cervix favourable, unfavourable or undefined.

The secondary reviews would have included all methods of labour induction for each of the categories of women for which subgroup analysis has been done in the primary reviews. There would have thus been six secondary reviews, of methods of labour induction in the following groups of women:

(1) nulliparous, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (2) nulliparous, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (3) multiparous, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (4) multiparous, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (5) previous caesarean section, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (6) previous caesarean section, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined).

Each time a primary review is updated with new data, those secondary reviews which included data which have changed, would also have been updated.

The trials included in the primary reviews were extracted from an initial set of trials covering all interventions used in induction of labour (see above for details of search strategy). The data extraction process was conducted centrally. This was co‐ordinated from the Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit (CESU) at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, UK, in co‐operation with the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group of the Cochrane Collaboration. This process allowed the data extraction process to be standardised across all the reviews.

The trials were initially reviewed on eligibility criteria, using a standardised form and the basic selection criteria specified above. Following this, data were extracted to a standardised data extraction form which was piloted for consistency and completeness. The pilot process involved the researchers at the CESU and previous reviewers in the area of induction of labour.

Information was extracted regarding the methodological quality of trials on a number of levels. This process was completed without consideration of trial results. Assessment of selection bias examined the process involved in the generation of the random sequence and the method of allocation concealment separately. These were then judged as adequate or inadequate using the criteria described in Table 4 for the purpose of the reviews.

1. Methodological quality of trials.

| Methodological item | Adequate | Inadequate |

| Generation of random sequence | Computer‐generated sequence, random number tables, lot drawing, coin tossing, shuffling cards, throwing dice. | Case number, date of birth, date of admission, alternation. |

| Concealment of allocation | Central randomisation, coded drug boxes, sequentially sealed opaque envelopes. | Open allocation sequence, any procedure based on inadequate generation. |

Performance bias was examined with regards to whom was blinded in the trials i.e. patient, caregiver, outcome assessor or analyst. In many trials the caregiver, assessor and analyst were the same party. Details of the feasibility and appropriateness of blinding at all levels was sought.

Predefined subgroup analyses are: previous caesarean section or not; nulliparity or multiparity; membranes intact or ruptured, and cervix unfavourable, favourable or undefined. Only those outcomes with data appear in the analysis tables.

Individual outcome data were included in the analysis if they met the pre‐stated criteria in 'Types of outcome measures'. Included trial data were processed as described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Clarke 2002). Data extracted from the trials were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis (when this was not done in the original report, re‐analysis was performed if possible). Where data were missing, clarification was sought from the original authors. If the attrition was such that it might significantly affect the results, these data were excluded from the analysis. This decision rested with the reviewers of primary reviews and is clearly documented. If missing data become available, they will be included in the analyses.

Data were extracted from all eligible trials to examine how issues of quality influence effect size in a sensitivity analysis. In trials where reporting was poor, methodological issues were reported as unclear or clarification sought.

Once the data had been extracted, they were distributed to individual reviewers for entry onto the Review Manager computer software (RevMan 2003), checked for accuracy, and analysed as above using the RevMan software. For dichotomous data, relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated, and in the absence of heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed‐effect model.

The predefined criteria for sensitivity analysis included all aspects of quality assessment as mentioned above, including aspects of selection, performance and attrition bias.

Primary analysis was limited to the prespecified outcomes and subgroup analyses. In the event of differences in unspecified outcomes or subgroups being found, these were analysed post hoc, but clearly identified as such to avoid drawing unjustified conclusions.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Caesarean section | 2 | 180 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.04 [0.92, 4.55] |

| 2 instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.10, 2.26] |

| 3 Meconium‐stained liquor | 2 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.23, 1.66] |

| 4 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 180 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Maternal side effects (all) | 2 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 59.92 [8.46, 424.52] |

| 6 Nausea (maternal) | 2 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 59.92 [8.46, 424.52] |

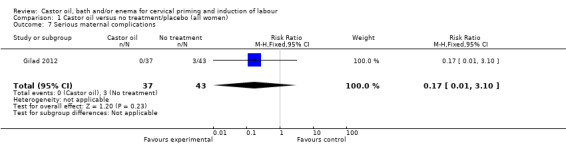

| 7 Serious maternal complications | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.17 [0.01, 3.10] |

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women), Outcome 4 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women), Outcome 5 Maternal side effects (all).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women), Outcome 7 Serious maternal complications.

Comparison 2. Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women, unfavourable cervix).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Caesarean section | 2 | 180 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.04 [0.92, 4.55] |

| 2 Meconium‐stained liquor | 2 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.23, 1.66] |

| 3 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 180 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Maternal side effects (all) | 2 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 59.92 [8.46, 424.52] |

| 5 Nausea (maternal) | 2 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 59.92 [8.46, 424.52] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women, unfavourable cervix), Outcome 1 Caesarean section.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women, unfavourable cervix), Outcome 2 Meconium‐stained liquor.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women, unfavourable cervix), Outcome 3 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women, unfavourable cervix), Outcome 4 Maternal side effects (all).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Castor oil versus no treatment/placebo (all women, unfavourable cervix), Outcome 5 Nausea (maternal).

Comparison 3. Castor oil versus no treatment (all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Caesarean section | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.31 [0.77, 6.87] |

| 2 Meconium‐stained liquor | 2 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.23, 1.66] |

| 3 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Maternal side effects (all) | 2 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 59.92 [8.46, 424.52] |

| 5 Nausea (maternal) | 2 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 59.92 [8.46, 424.52] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Castor oil versus no treatment (all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix), Outcome 1 Caesarean section.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Castor oil versus no treatment (all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix), Outcome 2 Meconium‐stained liquor.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Castor oil versus no treatment (all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix), Outcome 3 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Castor oil versus no treatment (all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix), Outcome 4 Maternal side effects (all).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Castor oil versus no treatment (all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix), Outcome 5 Nausea (maternal).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Azhari 2006.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 50 women requiring induction of labour. Inclusion criteria: 19‐35 years, gestational age 40‐42 weeks, singleton pregnancy, cephalic presentation, Bishops score less than or equal to 4, estimated fetal weight 2.5 to 4 kg. Exclusion criteria: medical or obstetric complications in current pregnancy, uterine activity, grand multiparity (6 or more pregnancies), use of other agents which may promote labour (enema, pelvic exams, coitus, nipple stimulation or other chemical or herbal agents). |

|

| Interventions | 60 mL single dose of castor oil diluted (n = 24), or no treatment (n = 23). | |

| Outcomes | Meconium‐stained liquor, maternal nausea. | |

| Notes | Hyperstimulation reported but not specified if with or without fetal heart rate changes. 3 post randomisation exclusions (1 from castor oil arm, 2 from control group). Emam‐Reza Hospital and Pastor Maternity Hospital, Mashdad, Iran. 6th August 2003 to 10th March 2004. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomised." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Unclear. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

Garry 2000.

| Methods | Alternation. | |

| Participants | 103 women requiring induction of labour. Inclusion criteria: singleton pregnancies, cephalic presentation, intact membranes, Bishops score < 4, no evidence of uterine contractions. Exclusion criteria: ruptured membranes, multiple gestations, oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth retardation, abnormal fetal heart rate tracings, biophysical profiles < 8, non‐cephalic presentations and maternal medical complications. |

|

| Interventions | 60 mL single dose of castor oil diluted in orange or apple juice (n = 52), or no treatment (n = 48). | |

| Outcomes | Spontaneous labour within 24 hours, mode of delivery, meconium‐stained liquor, maternal side effects, Apgar scores. | |

| Notes | 2 women in no treatment arm lost to follow‐up. 1 excluded due to inadvertent administration of castor oil. Saint Mary's Hospital, New York, USA. July 1992 to February 1993. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Inadequate. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

Gilad 2012.

| Methods | "randomised double blind." | |

| Participants | 80 women requiring induction of labour. Inclusion criteria: singleton, 40‐42 weeks, Bishops score < or equal to 7. Exclusion criteria: previous caesarean section, uterine activity. |

|

| Interventions | 60 mL of castor oil (n = 37) or 60 mL placebo (sunflower oil) (n = 43). | |

| Outcomes | Caesarean section, instrumental vaginal delivery, Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes, chorioamnionitis. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomised." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Azharkish 2008 | No English translation available. |

| Mathie 1959 | Comparison of castor oil, soap enema or hot bath. No primary outcomes presented. |

| Nabors 1958 | No primary outcomes presented. |

| Saberi 2008 | No primary outcomes reported in an extractable format. |

| Wang 1997 | Reviewed following translation. main comparison is multiple vaginal misoprostol (4 x 50 micrograms) versus 5 fried egg yolks (cooked) in rincinus oil). Also in this arm, participants received intravenous oxytocin within 12 hours. Hence the study does not use castor oil as a solitary intervention and also uses the egg yolks as a complex intervention with oxytocin in a different manner to the active (misoprostol) arm. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Porat 2006.

| Methods | "randomly and blindly divided into equal sized intervention group and control group." |

| Participants | 84 healthy women requiring induction. Inclusion criteria: 40‐42 weeks, singleton, intact membranes, Bishops score less than or equal to 4. Exclusion criteria: multiple pregnancy, oligo‐ or polyhydramnios, abnormal FHR tracing, obstetric complications, suspected growth restriction, previous uterine surgery. |

| Interventions | 60 mL of castor oil in 140 mL orange juice. Placebo group similar volume and texture. |

| Outcomes | Delivery within 24 hours of administration, neonatal Apgar scores, umbilical artery pH and base excess, neonatal complications and mode of delivery. |

| Notes | Proposed start date February 2006 and completion December 2008. Trial registry entry not updated since 2008. |

FHR: fetal heart rate

Contributions of authors

AJ Kelly and J Kavanagh performed the original data extraction. AJ Kelly, J Kavanagh and J Thomas drafted the original review and prepared the 2013 update

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Azhari 2006 {published data only}

- Azhari S, Pirdadeh S, Lotfalizadeh M, Shakeri MT. Evaluation of the effect of castor oil on initiating labor in term pregnancy. Saudi Medical Journal 2006;27(7):1011‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Garry 2000 {published data only}

- Garry D, Figueroa R, Guillaume J, Cucco V. Use of castor oil in pregnancies at term. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 2000;6:77‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gilad 2012 {published data only}

- Gilad R, Hochner H, Vinograd O, Saam R, Hochner‐Celnikier D, Porat S. The CIC Trial ‐ castor oil for induction of contractions in post‐term pregnancies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2012;206(Suppl 1):S77‐S78. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Azharkish 2008 {published data only}

- Azarkish F, Absalan N, Roudbari M, Barahooie F, Mirlashari S, Bameri M. Effect of oral castor oil on labor pain in post term pregnancy. Scientific Journal of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences 2008;13(3):e1‐e6, En1. [Google Scholar]

Mathie 1959 {published data only}

- Mathie JG, Dawson BH. Effect of castor oil, soap enema and hot bath on the pregnant uterus near term. British Medical Journal 1959;1:1162‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nabors 1958 {published data only}

- Nabors GC. Castor oil as an adjunct to induction of labor: critical re‐evaluation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1958;75:36‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saberi 2008 {published data only}

- Saberi F, Abedzadeh M, Sadat Z, Eslami A. Effect of castor oil on induction of labour. Journal of the Kashan University of Medical Sciences 2008; Vol. 11, issue 4.

Wang 1997 {published data only}

- Wang L, Shi C, Yang G. Comparison of misoprostol and ricinus oil meal for cervical ripening and labor induction. Chung‐Hua Fu Chan Ko Tsa Chih [Chinese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology] 1997;32(11):666‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Porat 2006 {published data only}

- Porat S. The use of castor oil as a labor initiator in post‐date pregnancies (planned trial). ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) (accessed 21 March 2006).

Additional references

Alfirevic 2006

- Alfirevic Z, Weeks A. Oral misoprostol for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001338.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alfirevic 2009

- Alfirevic Z, Kelly AJ, Dowswell T. Intravenous oxytocin alone for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003246.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boulvain 2001

- Boulvain M, Kelly AJ, Lohse C, Stan CM, Irion O. Mechanical methods for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001233] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boulvain 2005

- Boulvain M, Stan CM, Irion O. Membrane sweeping for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000451.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boulvain 2008

- Boulvain M, Kelly AJ, Irion O. Intracervical prostaglandins for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006971] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bricker 2000

- Bricker L, Luckas M. Amniotomy alone for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002862] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clarke 2002

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.1.5 [Updated April 2002]. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2002. Oxford: Update Software. Updated Quarterly.

Curtis 1987

- Curtis P, Evans S, Resnick J. Uterine hyperstimulation. The need for standard terminology. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1987;32:91‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

French 2001

- French L. Oral prostaglandin E2 for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003098] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hapangama 2009

- Hapangama D, Neilson James P. Mifepristone for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002865.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hofmeyr 2000

- Hofmeyr GJ, Alfirevic Z, Kelly AJ, Kavanagh J, Thomas J, Brocklehurst P, et al. Methods for cervical ripening and labour induction in late pregnancy: generic protocol. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002074] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hofmeyr 2009

- Hofmeyr GJ, Alfirevic Z, Kelly AJ, Kavanagh J, Thomas J, Neilson James P, et al. Methods for cervical ripening and labour induction in late pregnancy: generic protocol. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002074.pub2] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Hofmeyr 2010

- Hofmeyr GJ, Gülmezoglu AM, Pileggi C. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000941.pub2; CD000941] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Howarth 2001

- Howarth G, Botha DJ. Amniotomy plus intravenous oxytocin for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003250] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hutton 2001

- Hutton EK, Mozurkewich EL. Extra‐amniotic prostaglandin for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003092] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Jozwiak 2012

- Jozwiak M, Bloemenkamp KWM, Kelly AJ, Mol BWJ, Irion O, Boulvain M. Mechanical methods for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001233.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kavanagh 2001

- Kavanagh J, Kelly AJ, Thomas J. Sexual intercourse for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003093] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kavanagh 2005

- Kavanagh J, Kelly AJ, Thomas J. Breast stimulation for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003392.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kavanagh 2006

- Kavanagh J, Kelly AJ, Thomas J. Corticosteroids for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003100.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kavanagh 2006a

- Kavanagh J, Kelly AJ, Thomas J. Hyaluronidase for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003097.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kelly 2001

- Kelly Anthony J, Kavanagh J, Thomas J. Relaxin for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003103] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kelly 2009

- Kelly AJ, Malik S, Smith L, Kavanagh J, Thomas J. Vaginal prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGF2a) for induction of labour at term. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003101.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kelly 2011

- Kelly AJ, Munson C, Minden L. Nitric oxide donors for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006901.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Luckas 2000

- Luckas M, Bricker L. Intravenous prostaglandin for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002864] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Muzonzini 2004

- Muzonzini G, Hofmeyr GJ. Buccal or sublingual misoprostol for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004221.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2003 [Computer program]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 4.2 for Windows. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2003.

RevMan 2011 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

Smith 2003

- Smith CA. Homoeopathy for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003399] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smith 2004

- Smith CA, Crowther CA. Acupuncture for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002962.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thomas 2001

- Thomas J, Kelly AJ, Kavanagh J. Oestrogens alone or with amniotomy for cervical ripening or induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003393] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Kelly 2001a

- Kelly AJ, Kavanagh J, Thomas J. Castor oil, bath and/or enema for cervical priming and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003099] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]