ABSTRACT

Background

Breastfeeding modulates infant growth and protects against the development of obesity. However, whether or not maternal variation in human milk components, such as human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), is associated with programming of child growth remains unknown.

Objective

Our objective was to determine the association between maternal HMO composition and child growth during the first 5 y of life. In addition, the association between maternal prepregnancy BMI and HMO composition was assessed.

Methods

Human milk samples from 802 mothers were obtained from a prospective population-based birth cohort study, Steps to healthy development of Children (STEPS), conducted in Turku, Finland. HMO composition in these milk samples was analyzed by HPLC. Child growth data from 3 mo to 5 y were collected from municipal well-baby clinics and linked to maternal HMO composition data to test for associations.

Results

Maternal HMO composition 3 mo after delivery was associated with height and weight during the first 5 y of life in children of secretor mothers. Specifically, HMO diversity and the concentration of lacto-N-neo-tetraose (LNnT) were inversely associated and that of 2′-fucosyllactose (2′FL) was directly associated with child height and weight z scores in a model adjusted for maternal prepregnancy BMI, mode of delivery, birthweight z score, sex, and time. Maternal prepregnancy BMI was associated with HMO composition.

Conclusions

The association between maternal HMO composition and childhood growth may imply a causal relation, which warrants additional testing in preclinical and clinical studies, especially since 2′FL and LNnT are among the HMOs now being added to infant formula. Furthermore, altered HMO composition may mediate the impact of maternal prepregnancy BMI on childhood obesity, which warrants further investigation to establish the cause-and-effect relation.

Keywords: human milk oligosaccharides, breastfeeding, infant growth, childhood growth, maternal BMI

Introduction

Breastfeeding is associated with improved health both in infancy and later in life (1). Breastfeeding has been linked with long-term health benefits including reduced risk of developing obesity and type II diabetes mellitus (1–3), which has been suggested to be mediated by bioactive compounds in human milk (4); however, the contribution of individual human milk components remains poorly understood. The matter is further complicated by the fact that maternal obesity influences the microbiological, immunologic, lipid, and metabolite composition of human milk (5–7). In addition, maternal obesity (8, 9) and shorter duration of breastfeeding (1–3) are both well-established risk factors for childhood overweight. The contribution of individual breast milk components and their interindividual variation to child growth is currently unknown.

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) are a structurally complex and diverse group of glycans, which are present in human milk in high quantities (5–15 g/L in mature milk) (10). HMOs carry lactose at the reducing end, which can be further elongated by galactose- and N-acetyllactosamine-containing disaccharides, sialylated in α2–3- and α2–6-linkages as well as fucosylated in α1–2-, α1–3-, and α1–4- linkages. HMO fucosylation is catalyzed by fucosyltransferase enzymes with expression strongly controlled by genetics. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the gene encoding for fucosyltransferase 2 (FUT2), for example, introduce a premature stop codon, which inactivates the enzyme and leads to a near loss of α1–2-fucosylated HMOs such as 2′-fucosyllactose (2′FL) or lacto-N-fucopentaose 1 (LNFP1) in the milk of some women (nonsecretors). In contrast, women with an active FUT2 enzyme (secretors) produce and secrete high amounts of these α1–2-fucosylated HMOs in their milk [extensively reviewed in (10)]. In fact, the overall HMO composition profile between secretor and nonsecretor women is vastly different, which is why secretor status is often used to stratify cohort data.

HMOs are not digested by the infant but instead have a number of biological functions including selectively promoting the growth of specific microbes, inhibiting the adhesion and invasion of potential pathogens in the infant's gastrointestinal tract, and modulating host immune function and intestinal epithelial cell gene expression patterns (10). It is therefore conceivable that HMOs contribute to the long-term health benefits associated with breastfeeding. Although the HMO composition profile appears to be unique to each individual mother (11, 12), little is known about maternal factors that influence the expression of specific HMOs, or the long-term impact of maternal HMO composition on the child.

The purpose of this study was to elucidate the links between maternal prepregnancy BMI, HMO composition, and child growth in a birth cohort. The association between maternal prepregnancy BMI and HMO concentrations in milk samples collected at age 3 mo was investigated. In addition, we addressed the question of whether maternal HMO composition correlates with child growth during the first 5 y of life.

Methods

Study design and subjects

The present study is based on data from mothers and children participating in a longitudinal Finland cohort, Steps to healthy development of Children (the STEPS Study), which has previously been described in detail by Lagström et al. (13). Briefly, all Finnish- and Swedish-speaking mothers who delivered a living child between 1 January, 2008 and 31 March, 2010 in the Hospital District of Southwest Finland formed the cohort population (in total, 9811 mothers and their 9936 children). Altogether, 1797 mothers (18.3% of the total cohort) with 1827 neonates (including 30 pairs of twins) volunteered as participants for the intensive follow-up group of the STEPS Study. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland in February 2007.

Milk collection and infant feeding information

Mothers were asked to collect breast milk when the infant was aged 3 mo. Altogether, 812 of the 1797 mothers (45%) enrolled in the STEPS Study provided a breast milk sample. Breastfeeding information was not recorded for 572 of the 985 mothers from whom milk samples were not available. In total, 413 mothers breastfed at least for some time but did not provide a sample and only 19 mothers reported to never have initiated breastfeeding.

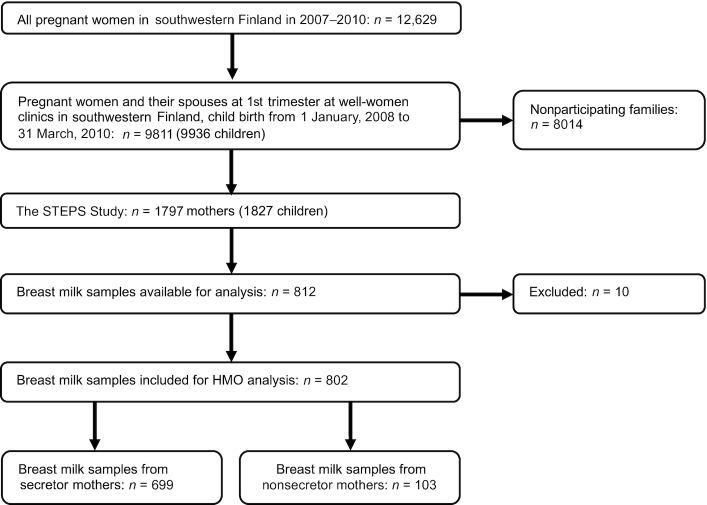

A total of 802 breast milk samples were analyzed with 10 samples excluded for technical reasons, including unclear labeling and insufficient sample quantity (Figure 1). The mean age of the infants at the time of milk collection was 11.3 wk (SD: 2.6 wk). Written instructions for the collection of the human milk sample were provided to the mothers, who obtained the samples by manual expression in the morning from a single breast, first milking a few drops to waste before collecting the actual sample (10 mL) into a plastic container. The mothers brought the samples to the research center or the samples were collected from their homes on the day of sampling. All samples were frozen and stored at −70°C immediately after expression until further analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart summarizing exclusion and inclusion criteria for present study samples from the STEPS Study. HMO, human milk oligosaccharide; the STEPS Study, Steps to healthy development of Children.

Background characteristics and growth data

Self-reported height and weight before pregnancy were collected from self-administered questionnaires upon recruitment for the calculation of maternal prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2). Information regarding maternal age and self-reported smoking habits (before and during pregnancy) were also obtained from the questionnaires during the prenatal period. Information regarding pregnancy duration, delivery as well as children's sex, birth weight, length, and possible twin brothers/sisters were obtained from the Longitudinal Census Files. Birth weight z scores were calculated using the previously published references specific to the Finnish population (14). Delivery was defined as premature if the pregnancy lasted ≤37 wk. The duration of exclusive and any breastfeeding was obtained from follow-up diaries completed by the mother in real time.

Child growth data were obtained from municipal follow-up clinics, which use standardized methods for the measurement of length/height and weight provided by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. The anthropometric data closest to the time points of 3, 6, and 8 mo and 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 y of age were used in the analyses. Growth charts specific for the Finnish population (15) were used to obtain population-specific z scores for height, weight, and BMI.

HMO analysis

HPLC was used to characterize HMOs in breast milk as previously described (16). Human milk was spiked with raffinose (a non-HMO carbohydrate) as an internal standard to allow absolute quantification. Oligosaccharides were extracted by high-throughput solid-phase extraction over C18 and carbograph microcolumns and fluorescently labeled with 2-aminobenzamide (2AB). Labeled oligosaccharides were analyzed by HPLC on an amide-80 column (15 cm length, 2 mm inner diameter, 3 μm particle size; Tosoh Bioscience) with a 50 mmol/L ammonium formate-acetonitrile buffer system. Separation was performed at 25°C and monitored with a fluorescence detector at 360 nm excitation and 425 nm emission. Peak annotation was based on standard retention times and MS analysis on a Thermo LCQ Duo Ion trap MS equipped with a nano-electrospray ionization-source. Absolute concentrations were calculated based on standard response curves for each of the annotated HMOs. The total concentration of HMOs was calculated as the sum of the annotated oligosaccharides. HMO-bound fucose and HMO-bound sialic acid were calculated on a molar basis. The proportion of each HMO comprising the total HMO concentration was also calculated. HMO Simpson's diversity (17) and evenness were calculated based on relative abundances of all annotated HMOs.

Secretor status determination

Maternal secretor status was determined by the high abundance (secretor) or near absence (nonsecretor) of the HMO 2′FL in the respective milk samples.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software for Windows version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.). The level of significance was set at P value <0.05. The clinical characteristics of the mothers and the children as well as HMO concentrations are expressed as medians and interquartiles (IQR; Q1, Q3) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. The comparisons of HMO concentrations between secretor and nonsecretor mothers were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test due to nonnormal data distributions.

ANCOVA was used to examine associations between each HMO variable and maternal prepregnancy BMI; the HMO variables included HMO diversity, HMO-bound fucose and sialic acid, the sum of 19 HMOs, and the concentrations of 19 individual HMOs. Natural logarithmic transformation was performed for all these HMO variables except for HMO diversity. Mode of delivery and sex of the child were selected as confounding factors. The explanatory variables (prepregnancy BMI and smoking during pregnancy) were treated as independent variables.

The relations between the explanatory factors in the models were examined by 1-factor ANOVA for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. If assumptions for parametric models were not met, the results obtained were compared with the results of the Kruskal–Wallis and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (within time) for categorical explanatory factors and with the Spearman's rank correlation coefficient for BMI. Nonparametric tests were used for the variable difucosyllacto-N-tetraose (DFLNT) in the models of whole data and secretors.

Hierarchical linear mixed models for repeated measurements of height and weight z scores were used to model their associations with HMO concentrations. The models included sex of the child, mode of delivery, birth weight z score, maternal prepregnancy BMI, time (years), HMO concentration, and HMO*time interaction as explanatory factors. The statistical models were built separately for HMO diversity, HMO-bound fucose and sialic acid, the sum of 19 HMOs as well as the concentrations of 19 individual HMOs as explanatory variables. Time was treated as a categorical variable. The models were built separately for the ages 3–12 mo and 1–5 y as well as for ages 3 mo to 5 y. Interaction between HMO concentration and time was included in the model to examine whether the mean change over time was different depending on HMO concentration. An unstructured covariance pattern was used for repeated measures. Normal distribution assumption was checked from studentized residuals.

The derived variable of the logarithm of 2′FL to the logarithm of lacto-N-neo-tetraose (LNnT) ratio was also examined using a hierarchical linear mixed model for repeated measurements. In addition, categorical variables were derived from the derived variable, logarithm of 2′FL, and logarithm of LNnT with quartiles (below 25Q versus 25Q–50Q versus 50Q–75Q versus above 75Q). Medians and quartiles of children's height z score and weight z score were calculated within the classes to examine height and weight.

Results

Study population

In total, 802 mother–child pairs were included in the study. Based on the abundance of the HMO 2′FL in the milk samples, 699 mothers (87.2%) were deemed to be secretors and 103 mothers (12.8%) nonsecretors. The clinical characteristics of the mothers and their infants included in this study as well as those in the original cohort are presented in detail in Table 1. The participant mothers were slightly older, were more often primiparous, had lower prepregnancy BMI, and smoked significantly less often during pregnancy. On the other hand, the participant children were less often premature, exhibited slightly higher birth weight, and lower birth weight z scores compared with the entire cohort.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of the mothers and children in the study presented as medians (IQR) or percentages1

| Variable | Total population 2 (n = 9009) | STEPS Study participants (n = 802) | P 3 | Secretors (n = 699) | Nonsecretors (n = 103) | P 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | ||||||

| Age, y | 30 (26, 33) | 31 (28, 34) | <0.001 | 31 (28, 34) | 31 (28, 34) | 0.87 |

| Prepregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 23.4 (21.1, 26.5) | 23.0 (21.0, 25.8) | 0.0334 | 23.0 (21.0, 25.8) | 23.5 (20.8, 25.8) | 0.984 |

| Previous births, % | 55 | 41 | <0.001 | 41 | 40 | 0.82 |

| Previous pregnancies, % | 66 | 53 | <0.001 | 53 | 52 | 0.87 |

| Caesarean section, % | 14 | 14 | 0.17 | 13 | 19 | 0.27 |

| Smoking during pregnancy, % | 18 | 7.8 | <0.001 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 0.97 |

| Children | ||||||

| Sex, boys, % | 51 | 54 | 0.12 | 53 | 56 | 0.54 |

| Duration of gestation, wk | 400/7 (391/7, 406/7) | 400/7 (39, 410/7) | 0.0184 | 400/7 (391/7, 410/7) | 400/7 (391/7, 410/7) | 0.904 |

| Premature birth, % | 5.7 | 3.4 | 0.013 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 0.76 |

| Birth weight, g | 3530 (3200, 3870) | 3540 (3280, 3860) | 0.033 | 3540 (3270, 3860) | 3530 (3320, 3870) | 0.43 |

| Birth weight, z score | −0.061 (−0.825, 0.686) | −0.014 (−0.669, 0.688) | 0.039 | −0.015 (−0.692, 0.695) | −0.002 (−0.634, 0.657) | 0.46 |

| Duration of any breastfeeding, mo | — | 10.0 (6.5, 12.4) | — | 10.1 (6.5, 12.4) | 9.7 (7.0, 12.6) | 0.804 |

Two-sample t test was used for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables. STEPS Study, Steps to healthy development of Children.

All Finnish women with 1 live birth from 1 January, 2008 to 31 December, 2010.

Difference between total population and STEPS Study participants.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used because of the exception of normal distribution.

Difference between secretors and nonsecretors.

HMO composition 3 mo after delivery and its association with maternal prepregnancy BMI

HMO concentrations in milk samples obtained 3 mo after delivery are presented in Supplemental Table 1. As expected, significant differences in HMO composition were detected between secretor and nonsecretor mothers. Secretor mothers exhibited significantly higher concentrations of fucosylated HMOs, whereas the HMO profile in nonsecretor mothers was more diverse (Supplemental Table 1).

The median maternal prepregnancy BMI in the entire study cohort was 23.0 (IQR 21.0–25.8). No significant differences in maternal BMI were detected between secretor and nonsecretor mothers. Maternal prepregnancy BMI was negatively correlated with HMO diversity in secretor but not in nonsecretor mothers (Table 2). The association was statistically significant in an ANCOVA model adjusted for mode of delivery, child sex, and maternal smoking during pregnancy. At the level of individual HMOs, maternal prepregnancy BMI was positively correlated with the concentration of 2′FL and negatively correlated with the concentration of LNnT in an ANCOVA model adjusted for mode of delivery, child sex, and maternal smoking during pregnancy in secretor mothers. The negative association between prepregnancy BMI and LNnT concentration was also detected when both secretors and nonsecretors were analyzed together, whereas no significant correlations between prepregnancy BMI and HMO concentrations were observed in nonsecretor mothers, possibly due to the lower number of samples.

TABLE 2.

The association between maternal BMI and HMO diversity and concentrations (nmol/mL)1

| Total (n = 481) | Secretors (n = 418) | Nonsecretors (n = 63) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI slope estimate (95% CI) | P | BMI slope estimate (95% CI) | P | BMI slope estimate (95% CI) | P | |

| Diversity | −0.03 (−0.06, 0.0005) | 0.054 | −0.04 (−0.08, −0.006) | 0.022 | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.07) | 0.40 |

| Sum of HMOs | −0.00007 (−0.004, 0.004) | 0.98 | 0.002 (−0.0001, 0.003) | 0.064 | −0.001 (−0.004, 0.001) | 0.30 |

| HMO-bound sialic acid | −0.002 (−0.008, 0.003) | 0.47 | −0.003 (−0.009, 0.002) | 0.24 | −0.001 (−0.01, 0.009) | 0.91 |

| HMO-bound fucose | −0.0002 (−0.008, 0.008) | 0.97 | 0.002 (−0.0002, 0.005) | 0.072 | 0.001 (−0.01, 0.02) | 0.88 |

| 2′FL | −0.004 (−0.04, 0.03) | 0.81 | 0.008 (0.0001, 0.02) | 0.046 | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | 0.55 |

| 3FL | 0.006 (−0.006, 0.02) | 0.33 | 0.008 (−0.002, 0.02) | 0.12 | 0.005 (−0.02, 0.03) | 0.71 |

| LNnT | −0.01 (−0.02, −0.003) | 0.006 | −0.012 (−0.02, −0.004) | 0.004 | −0.004 (−0.03, 0.02) | 0.73 |

| 3′SL | −0.003 (−0.01, 0.007) | 0.60 | −0.0005 (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.93 | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | 0.30 |

| DFLac | −0.002 (−0.04, 0.03) | 0.92 | 0.009 (−0.001, 0.02) | 0.094 | −0.006 (−0.08, 0.07) | 0.87 |

| 6′SL | −0.004 (−0.02, 0.009) | 0.57 | −0.006 (−0.02, 0.006) | 0.35 | −0.007 (−0.04, 0.03) | 0.71 |

| LNT | 0.0003 (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.96 | −0.001 (−0.01, 0.009) | 0.83 | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.05) | 0.50 |

| LNFP I | −0.003 (−0.03, 0.02) | 0.81 | 0.001 (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.85 | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.05) | 0.38 |

| LNFP II | −0.006 (−0.02, 0.003) | 0.22 | −0.009 (−0.02, 0.0002) | 0.054 | 0.001 (−0.02, 0.02) | 0.91 |

| LNFP III | −0.005 (−0.02, 0.006) | 0.38 | −0.008 (−0.02, 0.003) | 0.16 | 0.006 (−0.02, 0.03) | 0.61 |

| LSTb | −0.004 (−0.01, 0.006) | 0.45 | −0.005 (−0.02, 0.006) | 0.37 | −0.005 (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.54 |

| LSTc | 0.009 (−0.003, 0.02) | 0.12 | 0.01 (−0.002, 0.02) | 0.096 | −0.0005 (−0.03, 0.03) | 0.98 |

| DFLNT | −0.02 (−0.03, 0.001) | 0.069 | −0.02 (−0.03, 0.001) | 0.068 | −0.002 (−0.03, 0.03) | 0.91 |

| LNH | −0.004 (−0.02, 0.009) | 0.54 | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.004) | 0.16 | 0.03 (−0.004, 0.07) | 0.077 |

| DSLNT | −0.008 (−0.02, 0.001) | 0.093 | −0.007 (−0.02, 0.004) | 0.21 | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.008) | 0.20 |

| FLNH | −0.0007 (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.93 | −0.002 (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.82 | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.06) | 0.43 |

| DFLNH | −0.002 (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.80 | 0.0002 (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.97 | 0.006 (−0.03, 0.04) | 0.72 |

| FDSLNH | −0.004 (−0.02, 0.008) | 0.54 | −0.009 (−0.02, 0.003) | 0.15 | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.04) | 0.25 |

| DSLNH | −0.006 (−0.006, 0.02) | 0.36 | 0.003 (−0.01, 0.02) | 0.67 | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.04) | 0.32 |

In addition to maternal prepregnancy BMI, the models included mode of delivery, child sex, and smoking during pregnancy as explanatory factors. The estimate (95% CI) is the slope indicating association between maternal prepregnancy BMI and HMO diversity and concentrations. Statistical analyses were performed with ANCOVA. DFLac, difucosyllactose; DFLNH, difucosyllacto-N-hexaose; DFLNT, difucosyllacto-N-tetraose; DSLNH, disialyllacto-N-hexaose; DSLNT, disialyllacto-N-tetraose; FDSLNH, fucosyldisialyllacto-N-hexaose; FLNH, fucosyllacto-N-hexaose; HMO, human milk oligosaccharide; LNFP, lacto-N-fucopentaose; LNH, lacto-N-hexaose; LNnT, lacto-N-neotetraose; LNT, lacto-N-tetraose; LSTb, sialyllacto-N-tetraose b; LSTc, sialyllacto-N-tetraose c; 2′FL, 2′-fucosyllactose; 3FL, 3-fucosyllactose; 3′SL, 3′-sialyllactose; 6′SL, 6′-sialyllactose.

HMO concentrations and child height and weight during the first 5 y of life

HMO diversity, assessed 3 mo after delivery, was negatively correlated with height (Table 3) and weight (Table 4) z scores during the first 12 mo of life in children of secretor mothers. These associations were statistically significant in a hierarchical linear mixed model adjusted for child sex, maternal prepregnancy BMI, birth weight z score, and time point. The correlation remained significant throughout 1 and 5 y of age between HMO diversity and height z scores but was no longer evident between HMO diversity and weight z scores after 1 y of age. No correlations between HMO diversity and length or height z scores were detected in children of nonsecretor mothers.

TABLE 3.

The association between HMO concentrations (nmol/mL) (ln-transformed data) and height z score in children aged 3–12 mo and aged 1–5 y separately for children of secretor and nonsecretor mothers1

| Children aged 3–12 mo | Children aged 1–5 y | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secretor mothers (n = 674) | Nonsecretor mothers (n = 100) | Secretor mothers (n = 674) | Nonsecretor mothers (n = 100) | |||||

| Estimate (95% CI)2 | P | Estimate (95% CI)2 | P | Estimate (95% CI)2 | P | Estimate (95% CI)2 | P | |

| Diversity | −0.059 (−0.100, −0.017) | 0.006 | 0.061 (−0.122, 0.243) | 0.51 | −0.050 (−0.094, −0.006) | 0.027 | 0.099 (−0.089, 0.286) | 0.30 |

| Sum of HMOs | 0.768 (−0.150, 1.687) | 0.10 | −1.093 (−3.872, 1.687) | 0.44 | 0.665 (−0.314, 1.644) | 0.18 | −0.368 (−3.218, 2.482) | 0.80 |

| HMO-bound Sialic acid | −0.153 (−0.417, 0.111) | 0.26 | −0.573 (−1.471, 0.325) | 0.21 | −0.114 (−0.393, 0.166) | 0.42 | −0.094 (−1.044, 0.856) | 0.84 |

| HMO-bound Fucose | 0.788 (0.199, 1.376) | 0.009 | 0.123 (−0.394, 0.640) | 0.64 | 0.707 (0.078, 1.337) | 0.028 | −0.268 (−0.804, 0.269) | 0.33 |

| 2′FL | 0.229 (0.042, 0.416) | 0.016 | −0.016 (−0.186, 0.154) | 0.85 | 0.197 (−0.002, 0.397) | 0.053 | 0.019 (−0.155, 0.192) | 0.83 |

| 3FL | 0.064 (−0.087, 0.215) | 0.41 | 0.049 (−0.188, 0.287) | 0.68 | 0.106 (−0.056, 0.268) | 0.20 | 0.011 (−0.237, 0.258) | 0.93 |

| LNnT | −0.255 (−0.428, −0.082) | 0.004 | −0.053 (−0.367, 0.262) | 0.74 | −0.247 (−0.432, −0.062) | 0.009 | 0.119 (−0.210, 0.448) | 0.48 |

| 3′SL | 0.106 (−0.034, 0.246) | 0.14 | −0.067 (−0.479, 0.345) | 0.75 | 0.125 (−0.025, 0.275) | 0.10 | 0.113 (−0.313, 0.538) | 0.60 |

| DFLac | 0.028 (−0.118, 0.174) | 0.71 | 0.047 (−0.065, 0.160) | 0.40 | 0.026 (−0.129, 0.182) | 0.74 | 0.032 (−0.086, 0.151) | 0.59 |

| 6′SL | −0.107 (−0.238, 0.024) | 0.11 | −0.219 (−0.465, 0.026) | 0.079 | −0.072 (−0.211, 0.067) | 0.31 | −0.055 (−0.316, 0.206) | 0.67 |

| LNT | −0.077 (−0.224, 0.070) | 0.30 | 0.057 (−0.156, 0.271) | 0.59 | −0.082 (−0.239, 0.074) | 0.30 | 0.104 (−0.112, 0.320) | 0.34 |

| LNFP I | −0.015 (−0.126, 0.097) | 0.80 | 0.069 (−0.088, 0.227) | 0.39 | −0.022 (−0.142, 0.097) | 0.72 | −0.025 (−0.190, 0.140) | 0.77 |

| LNFP II | −0.126 (−0.295, 0.042) | 0.14 | −0.029 (−0.334, 0.277) | 0.85 | −0.168 (−0.349, 0.013) | 0.069 | −0.054 (−0.369, 0.261) | 0.73 |

| LNFP III | −0.037 (−0.180, 0.104) | 0.61 | 0.152 (−0.123, 0.427) | 0.28 | −0.034 (−0.186, 0.118) | 0.66 | −0.041 (−0.325, 0.242) | 0.77 |

| LSTb | −0.136 (−0.265, −0.008) | 0.038 | 0.180 (−0.265, 0.625) | 0.42 | −0.108 (−0.247, 0.030) | 0.12 | 0.289 (−0.173, 0.750) | 0.22 |

| LSTc | 0.053 (−0.068, 0.173) | 0.39 | 0.138 (−0.146, 0.422) | 0.34 | 0.042 (−0.086, 0.171) | 0.52 | 0.068 (−0.229, 0.364) | 0.65 |

| DFLNT | −0.008 (−0.090, 0.074) | 0.85 | 0.111 (−0.184, 0.406) | 0.46 | −0.0001 (−0.087, 0.087) | 1.00 | 0.090 (−0.216, 0.396) | 0.56 |

| LNH | −0.028 (−0.137, 0.081) | 0.62 | 0.101 (−0.114, 0.316) | 0.36 | 0.011 (−0.106, 0.127) | 0.86 | −0.036 (−0.259, 0.186) | 0.75 |

| DSLNT | −0.087 (−0.216, 0.042) | 0.18 | 0.049 (−0.276, 0.373) | 0.77 | −0.110 (−0.248, 0.029) | 0.12 | 0.256 (−0.078, 0.589) | 0.13 |

| FLNH | 0.008 (−0.086, 0.101) | 0.87 | 0.046 (−0.128, 0.219) | 0.60 | 0.030 (−0.070, 0.130) | 0.55 | 0.008 (−0.173, 0.188) | 0.93 |

| DFLNH | −0.007 (−0.140, 0.126) | 0.92 | 0.085 (−0.129, 0.299) | 0.43 | −0.052 (−0.193, 0.089) | 0.47 | 0.005 (−0.217, 0.228) | 0.96 |

| FDSLNH | −0.035 (−0.154, 0.085) | 0.57 | −0.010 (−0.272, 0.252) | 0.94 | −0.041 (−0.169, 0.086) | 0.52 | −0.147 (−0.418, 0.124) | 0.29 |

| DSLNH | 0.033 (−0.079, 0.146) | 0.56 | −0.040 (−0.357, 0.278) | 0.81 | 0.030 (−0.090, 0.150) | 0.62 | 0.022 (−0.311, 0.354) | 0.90 |

Statistical associations were tested with a hierarchical linear mixed model for repeated measurements. The models include mode of delivery, sex, birth weight z score, maternal prepregnancy BMI, HMO, time, and HMO*time interaction as explanatory factors. DFLac, difucosyllactose; DFLNH, difucosyllacto-N-hexaose; DFLNT, difucosyllacto-N-tetraose; DSLNH, disialyllacto-N-hexaose; DSLNT, disialyllacto-N-tetraose; FDSLNH, fucosyldisialyllacto-N-hexaose; FLNH, fucosyllacto-N-hexaose; HMO, human milk oligosaccharide; LNFP, lacto-N-fucopentaose; LNH, lacto-N-hexaose; LNnT, lacto-N-neotetraose; LNT, lacto-N-tetraose; LSTb, sialyllacto-N-tetraose b; LSTc, sialyllacto-N-tetraose c; 2′FL, 2′-fucosyllactose; 3FL, 3-fucosyllactose; 3′SL, 3′-sialyllactose; 6′SL, 6′-sialyllactose.

A negative slope estimate indicates a negative correlation between child's height z scores and ln-transformed HMO concentrations and a positive slope estimate indicates a positive correlation. The 95% CI of the estimate is given in parentheses. The estimate of the HMO variable is the coefficient of main effect of HMO.

TABLE 4.

The association between HMO concentrations (nmol/mL) (ln-transformed data) and weight z score in children aged 3–12 mo and aged 1–5 y separately by maternal secretors and nonsecretors1

| Children aged 3–12 mo | Children aged 1–5 y | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secretor mothers (n = 674) | Nonsecretor mothers (n = 100) | Secretor mothers (n = 674) | Nonsecretor mothers (n = 100) | |||||

| Estimate (95% CI)2 | P | Estimate (95% CI)2 | P | Estimate (95% CI)2 | P | Estimate (95% CI)2 | P | |

| Diversity | −0.048 (−0.087, −0.009) | 0.017 | 0.093 (−0.091, 0.278) | 0.32 | −0.038 (−0.079, 0.002) | 0.063 | 0.103 (−0.076, 0.283) | 0.25 |

| Sum of HMOs | 0.901 (0.032, 1.771) | 0.042 | −3.086 (−5.819, −0.353) | 0.027 | 0.828 (−0.063, 1.718) | 0.068 | −1.253 (−3.961, 1.455) | 0.36 |

| HMO-bound sialic acid | −0.018 (−0.268, 0.233) | 0.89 | −0.187 (−1.090, 0.717) | 0.68 | 0.030 (−0.225, 0.284) | 0.82 | −0.030 (−0.930, 0.870) | 0.95 |

| HMO-bound fucose | 0.837 (0.280, 1.394) | 0.003 | 0.113 (−0.409, 0.634) | 0.67 | 0.610 (0.037, 1.183) | 0.037 | −0.095 (−0.609, 0.418) | 0.71 |

| 2′FL | 0.210 (0.033, 0.387) | 0.020 | −0.017 (−0.189, 0.156) | 0.85 | 0.165 (−0.016, 0.347) | 0.075 | 0.029 (−0.137, 0.195) | 0.73 |

| 3FL | 0.182 (0.039, 0.324) | 0.012 | 0.141 (−0.097, 0.378) | 0.24 | 0.162 (0.014, 0.309) | 0.032 | 0.134 (−0.102, 0.370) | 0.26 |

| LNnT | −0.225 (−0.389, −0.061) | 0.007 | −0.194 (−0.508, 0.120) | 0.22 | −0.213 (−0.381, −0.044) | 0.014 | −0.062 (−0.377, 0.253) | 0.70 |

| 3′SL | 0.161 (0.028, 0.293) | 0.017 | 0.151 (−0.265, 0.567) | 0.47 | 0.153 (0.017, 0.289) | 0.028 | 0.290 (−0.116, 0.696) | 0.16 |

| DFLac | 0.154 (0.016, 0.292) | 0.028 | −0.013 (−0.127, 0.102) | 0.83 | 0.115 (−0.026, 0.256) | 0.11 | −0.008 (−0.121, 0.106) | 0.89 |

| 6′SL | −0.075 (−0.199, 0.049) | 0.23 | −0.375 (−0.612, −0.138) | 0.002 | −0.012 (−0.140, 0.115) | 0.85 | −0.145 (−0.392, 0.101) | 0.25 |

| LNT | −0.136 (−0.275, 0.002) | 0.053 | 0.121 (−0.095, 0.336) | 0.27 | −0.091 (−0.234, 0.051) | 0.21 | 0.103 (−0.103, 0.310) | 0.32 |

| LNFP I | −0.090 (−0.195, 0.016) | 0.10 | 0.060 (−0.100, 0.219) | 0.46 | −0.061 (−0.169, 0.048) | 0.27 | −0.039 (−0.196, 0.118) | 0.62 |

| LNFP II | −0.031 (−0.191, 0.129) | 0.71 | −0.002 (−0.307, 0.303) | 0.99 | −0.091 (−0.256, 0.075) | 0.28 | −0.062 (−0.365, 0.242) | 0.69 |

| LNFP III | 0.056 (−0.079, 0.191) | 0.42 | −0.027 (−0.304, 0.251) | 0.85 | 0.043 (−0.096, 0.182) | 0.54 | 0.003 (−0.270, 0.275) | 0.99 |

| LSTb | −0.149 (−0.271, −0.027) | 0.017 | 0.082 (−0.370, 0.534) | 0.72 | −0.071 (−0.197, 0.055) | 0.27 | 0.222 (−0.223, 0.666) | 0.32 |

| LSTc | 0.037 (−0.077, 0.150) | 0.53 | −0.021 (−308, 0.265) | 0.88 | 0.033 (−0.085, 0.149) | 0.59 | 0.059 (−0.224, 0.342) | 0.68 |

| DFLNT | −0.049 (−0.127, 0.028) | 0.21 | −0.003 (−0.302, 0.296) | 0.99 | −0.058 (−0.137, 0.021) | 0.15 | −0.014 (−0.308, 0.280) | 0.92 |

| LNH | 0.024 (−0.079, 0.127) | 0.65 | 0.143 (−0.071, 0.358) | 0.19 | 0.021 (−0.085, 0.127) | 0.70 | 0.008 (−0.204, 0.220) | 0.94 |

| DSLNT | −0.114 (−0.236, 0.009) | 0.068 | 0.101 (−0.226, 0.427) | 0.54 | −0.068 (−0.194, 0.058) | 0.29 | 0.170 (−0.152, 0.491) | 0.30 |

| FLNH | −0.022 (−0.110, 0.066) | 0.62 | 0.046 (−0.129, 0.221) | 0.60 | −0.018 (−0.109, 0.073) | 0.69 | 0.022 (−0.151, 0.194) | 0.80 |

| DFLNH | −0.032 (−0.157, 0.094) | 0.62 | −0.039 (−0.254, 0.176) | 0.72 | −0.059 (−0.188, 0.069) | 0.37 | −0.025 (−0.238, 0.189) | 0.82 |

| FDSLNH | 0.058 (−0.055, 0.172) | 0.31 | 0.228 (−0.033, 0.490) | 0.086 | 0.003 (−0.114, 0.120) | 0.96 | 0.026 (−0.234, 0.287) | 0.84 |

| DSLNH | 0.094 (−0.013, 0.200) | 0.085 | −0.031 (−0.352, 0.289) | 0.85 | 0.079 (−0.031, 0.188) | 0.16 | −0.102 (−0.420, 0.215) | 0.52 |

Statistical associations were tested with a hierarchical linear mixed model for repeated measurements. The models include mode of delivery, sex, birth weight z score, maternal prepregnancy BMI, HMO, time, and HMO*time interaction as explanatory factors. DFLac, difucosyllactose; DFLNH, difucosyllacto-N-hexaose; DFLNT, difucosyllacto-N-tetraose; DSLNH, disialyllacto-N-hexaose; DSLNT, disialyllacto-N-tetraose; FDSLNH, fucosyldisialyllacto-N-hexaose; FLNH, fucosyllacto-N-hexaose; HMO, human milk oligosaccharide; LNFP, lacto-N-fucopentaose; LNH, lacto-N-hexaose; LNnT, lacto-N-neotetraose; LNT, lacto-N-tetraose; LSTb, sialyllacto-N-tetraose b; LSTc, sialyllacto-N-tetraose c; 2′FL, 2′-fucosyllactose; 3FL, 3-fucosyllactose; 3′SL, 3′-sialyllactose; 6′SL, 6′-sialyllactose.

A negative slope estimate indicates a negative correlation between child's weight z score and ln-transformed HMO concentrations and a positive slope estimate indicates a positive correlation. The 95% CI of the estimate is given in parentheses. The estimate of the HMO variable is the coefficient of main effect of HMO.

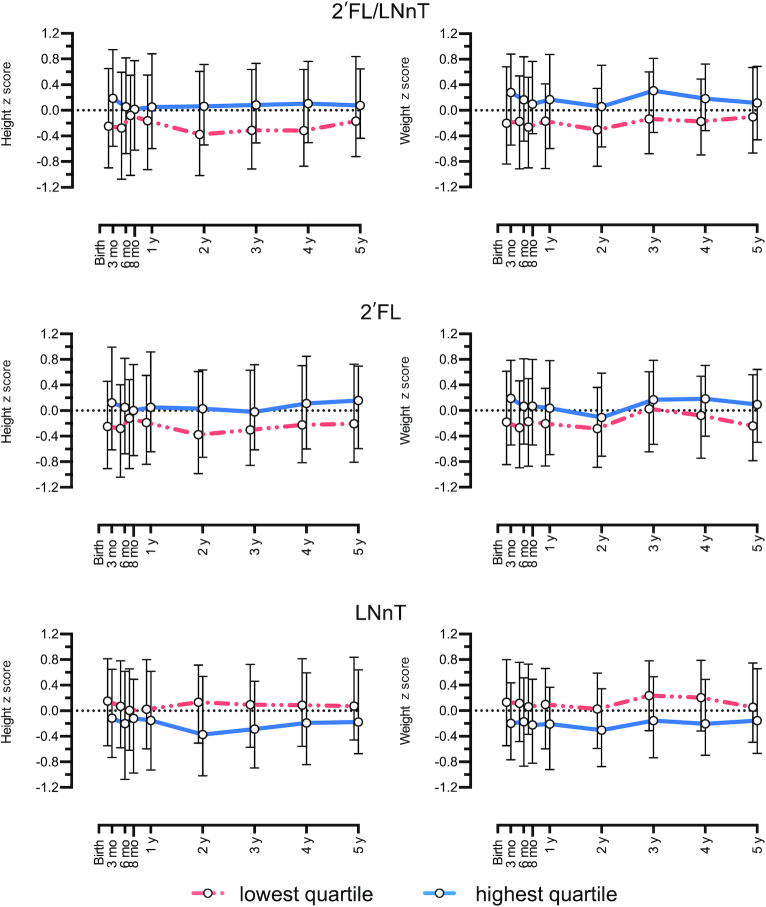

The concentrations of several individual HMOs exhibited significant correlations with child height (Table 3, Supplemental Table 2) and weight (Table 4, Supplemental Table 3) z scores throughout the first 5 y of life in children of secretor mothers. In the adjusted hierarchical linear mixed model, the concentration of 2′FL was positively correlated with height z scores between 3 and 12 mo and 1 and 5 y of age (Table 3) and weight z scores between 3 and 12 mo of age (Table 4). Conversely, the concentration of LNnT was negatively correlated with weight and length z scores throughout the first 5 y of life. The 2′FL/LNnT ratio consequently exhibited significant association with height and weight z scores from 3 mo to 5 y of age in children of secretor mothers (Figure 2) but not in children of nonsecretor mothers (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

FIGURE 2.

Children's height and weight z score from 3 mo to 5 y of age related to medians of the lowest (below 25) and highest (above 75) quartiles of the 2′FL/LNnT ratio, 2′FL, and LNnT in the group of secretor mothers (n = 699). Log-transformed data. LNnT, lacto-N-neotetraose; 2′FL, 2′-fucosyllactose.

Discussion

Breastfeeding modifies childhood growth and modestly reduces the risk of childhood overweight and obesity (3, 18). In the present study, the HMO composition in human milk 3 mo after delivery was significantly associated with childhood growth throughout the first 5 y of life. Specifically, HMO diversity and the concentration of LNnT were inversely associated and that of 2′FL was directly associated with child height and weight between the ages of 3 and 12 mo in children of secretor mothers. These data are consistent with the results of a previous study reporting human milk HMO diversity 1 mo after delivery is inversely correlated with infant fat mass at the same age and higher concentrations of LNnT are associated with lower body fat at the age of 6 mo (16). Our current results provide the first evidence for an association between HMOs and child growth beyond infancy and breastfeeding by indicating a significant association between HMO diversity and LNnT concentration and child height and weight also between the ages of 1 and 5 y. Our results suggest that individual differences in HMO composition may modulate the impact of breastfeeding on growth.

Obtaining high-quality scientific evidence on the effects of breastfeeding on growth and long-term health is difficult since conducting randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled trials on breastfeeding is impossible for obvious ethical and practical reasons. Epidemiological and cohort studies are prone to confounding by factors known to affect both breastfeeding initiation and/or duration and child growth and risk of obesity. Previous studies indicate that maternal smoking (19), high prepregnancy BMI (20), and caesarean section delivery (21) are all associated with reduced breastfeeding rates. Given the known associations between maternal BMI and the microbiological, immunologic, lipid, and metabolite composition of human milk (5–7), we wanted to investigate whether maternal HMO profiles also vary according to maternal BMI. Prepregnancy BMI exhibited a negative correlation with HMO diversity and the concentration of LNnT, whereas a positive association was detected between prepregnancy BMI and the concentration of 2′FL in secretor mothers in an analysis adjusted for maternal smoking during pregnancy, mode of delivery, and child sex. This is, to our knowledge, the first study to demonstrate that HMO composition may be dependent on maternal prepregnancy BMI.

It is striking that HMO diversity and the concentrations of LNnT and 2′FL were associated with both maternal prepregnancy BMI and child growth during the first 5 y of age. Maternal obesity is a major risk factor for excessive fetal growth (22) and childhood overweight and obesity (9, 18). It is therefore vitally important to rule out the possibility that the observed HMO profiles are merely an indicator of maternal prepregnancy BMI but have no direct association with child growth. Mode of delivery has also been reported to modulate both human milk composition (23) and childhood growth patterns (24). In our analyses adjusted for maternal prepregnancy BMI, birth weight z scores, mode of delivery, and child sex, significant associations between HMO composition and child growth were detected. We interpret this to suggest that although prenatal exposures such as maternal prepregnancy BMI affect both HMO composition and childhood growth, HMO composition may independently modulate growth patterns after birth and up to the age of 5 y. Establishing whether a causal relation exists between HMO profiles and growth patterns is beyond the scope of this observational study and this hypothesis needs to be tested using experimental and interventional designs.

It is intriguing to speculate that the association between maternal milk HMO composition and infant growth might be mediated via the developing infant gut microbiota. HMOs are known to specifically modulate the gut microbiota by promoting the growth of specific organisms such as bifidobacteria (10, 25). On the other hand, epidemiological and experimental studies indicate that early-life gut microbiota is causally associated with the development of both the growth failure associated with malnutrition (26) and the development of overweight and obesity (27, 28). Unfortunately, however, fecal samples were not analyzed from the infants in the present study.

The present study is purely observational and thus provides only associations without proving causal relations. Nonetheless, the large unselected prospective cohort followed with a standardized protocol and statistical analyses adjusted for confounding factors considerably improve the reliability and relevance of the observed associations. The study has some limitations. Relatively subtle differences between the participants and the subjects in the entire birth cohort were detected, which may to some extent compromise the generalizability of the results. Relying on self-reported weight and height may lead to inaccuracies in the calculation of prepregnancy BMI (29). Moreover, underreporting of weight and overreporting of height may result in systematic bias. This limitation must be taken into consideration when interpreting our results. Maternal BMI after delivery was unfortunately not available. On the other hand, the weights and lengths of the children were measured by healthcare professionals using standardized methods, which limits measurement error. Data on the performance of actual individual measurements were not available and variance in performance may have resulted in error. Not all factors potentially affecting HMO concentration or child growth, including maternal diet or infant and child morbidity were available. Furthermore, relying on a single human milk sample for each mother is an obvious limitation of the study since compositional changes within subjects over time are possible. It is of note, however, that all human milk samples in the study were collected 3 mo after delivery from mothers living in Southwest Finland, which diminishes the potentially confounding impact of lactation stage (30) or geographical area (31) on HMO concentrations. All infants in the study were at least partially breastfed at the age of 3 mo and the median duration of breastfeeding was 10 mo, which implies that sufficient exposure to breast milk and HMOs was achieved to elicit physiological effects on growth.

Most of the observed associations were statistically significant in secretor mothers only, which may simply reflect the much higher number of secretor mothers (n = 699) in our study compared with nonsecretors (n = 103). 2′FL specifically and per definition is almost absent in the milk of nonsecretor mothers, which is likely another reason why there was no significant association between either 2′FL or 2′FL/LNnT and maternal factors or infant/childhood outcomes.

The results of the present study suggest that 1) the HMO composition of milk varies depending on maternal prepregnancy BMI and 2) HMOs may be 1 mediator of the programming of child growth attributed to breast milk. These notions have several clinical implications. Differences in individual HMO composition may provide 1 explanation for the discrepant data on the impact of breastfeeding on child growth. In particular, the association between maternal prepregnancy BMI and HMO profiles may contribute to the increased obesity risk in children of obese mothers. Furthermore, if a causal relation with specific HMOs and childhood growth patterns is established, new nutritional interventions may be developed that 1) aim to modulate HMO composition in maternal milk or 2) provide specific HMOs to infants or children to support healthy childhood growth and development. In fact, some infant formula products already contain either 2′FL alone or a combination of 2′FL and LNnT (32). Although the currently added amounts of 2′FL (0.2 or 0.8 g/L) are below the concentrations we measured in human milk samples in the current study (median 2.96 g/L), it will be important to understand how different HMOs alone and in combination affect infant short- and long-term growth and development.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge Eliisa Löyttyniemi for statistical consultation and Ulla Sankilampi for providing the algorithms for z score calculations. We are also grateful to all the families who took part in this study.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows— LB, HL, SR: concept and design; CY, JG: acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; LB, HL, SR: drafting of the manuscript; all authors: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; AK, HO: statistical analysis; LB, HL, SR: supervision; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Notes

Supported by grant R21-HD088953 (PI: LB) from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. LB's effort is in part supported by an endowed gift through the Family Larsson-Rosenquist Foundation, Switzerland. The study sponsors had no role in the study design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplemental Tables 1–3 and Supplemental Figures 1 and 2 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request.

Abbreviations used: FUT2, fucosyltransferase 2; HMO, human milk oligosaccharide; LNnT, lacto-N-neo-tetraose; the STEPS Study, Steps to healthy development of Children; 2′FL, 2′-fucosyllactose.

References

- 1. Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, França GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, Murch S, Sankar MJ, Walker N, Rollins NC et al.. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Camargo CA Jr, Berkey CS, Frazier AL, Rockett HR, Field AE, Colditz GA. Risk of overweight among adolescents who were breastfed as infants. JAMA. 2001;285(19):2461–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patro-Gołąb B, Zalewski BM, Kołodziej M, Kouwenhoven S, Poston L, Godfrey KM, Koletzko B, van Goudoever JB, Szajewska H. Nutritional interventions or exposures in infants and children aged up to 3 years and their effects on subsequent risk of overweight, obesity and body fat: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Obes Rev. 2016;17(12):1245–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rautava S, Walker WA. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine founder's lecture 2008: breastfeeding – an extrauterine link between mother and child. Breastfeed Med. 2009;4(1):3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collado MC, Laitinen K, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Maternal weight and excessive weight gain during pregnancy modify the immunomodulatory potential of breast milk. Pediatr Res. 2012;72(1):77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mäkelä J, Linderborg K, Niinikoski H, Yang B, Lagström H. Breast milk fatty acid composition differs between overweight and normal weight women: the STEPS Study. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52(2):727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Isganaitis E, Venditti S, Matthews TJ, Lerin C, Demerath EW, Fields DA. Maternal obesity and the human milk metabolome: associations with infant body composition and postnatal weight gain. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110(1):111–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tun HM, Bridgman SL, Chari R, Field CJ, Guttman DS, Becker AB, Mandhane PJ, Turvey SE, Subbarao P, Sears MR et al.. Roles of birth mode and infant gut microbiota in intergenerational transmission of overweight and obesity from mother to offspring. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(4):368–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Voerman E, Santos S, Patro Golab B, Amiano P, Ballester F, Barros H, Bergström A, Charles MA, Chatzi L, Chevrier C et al.. Maternal body mass index, gestational weight gain, and the risk of overweight and obesity across childhood: an individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(2):e1002744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bode L. Human milk oligosaccharides: every baby needs a sugar mama. Glycobiology. 2012;22(9):1147–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chaturvedi P, Warren CD, Altaye M, Morrow AL, Ruiz-Palacios G, Pickering LK, Newburg DS. Fucosylated human milk oligosaccharides vary between individuals and over the course of lactation. Glycobiology. 2001;11:365–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thurl S, Munzert M, Henker J, Boehm G, Müller-Werner B, Jelinek J, Stahl B. Variation of human milk oligosaccharides in relation to milk groups and lactational periods. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:1261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lagström H, Rautava P, Kaljonen A, Räihä H, Pihlaja P, Korpilahti P, Peltola V, Rautakoski P, Österbacka E, Niemi P et al.. Cohort profile: steps to the healthy development and well-being of children (the STEPS Study). Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1273–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sankilampi U, Hannila ML, Saari A, Gissler M, Dunkel L. New population-based references for birth weight, length, and head circumference in singletons and twins from 23 to 43 gestation weeks. Ann Med. 2013;45:446–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saari A, Sankilampi U, Hannila ML, Kiviniemi V, Kesseli K, Dunkel L. New Finnish growth references for children and adolescents aged 0 to 20 years: length/height-for-age, weight-for-length/height, and body mass index-for-age. Ann Med. 2011;43(3):235–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alderete TL, Autran C, Brekke BE, Knight R, Bode L, Goran MI, Fields DA. Associations between human milk oligosaccharides and infant body composition in the first 6 mo of life. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(6):1381–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DeJong TM. A comparison of three diversity indices based on their components of richness and evenness. Oikos. 1975;26:222–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, Yang M, Glazebrook CP. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(12):1019–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Napierala M, Mazela J, Merritt TA, Florek E. Tobacco smoking and breastfeeding: effect on the lactation process, breast milk composition and infant development. A critical review. Environ Res. 2016;151:321–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang Y, Ouyang YQ, Redding SR. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and cessation of breastfeeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breastfeed Med. 2019;14(6):366–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hobbs AJ, Mannion CA, McDonald SW, Brockway M, Tough SC. The impact of caesarean section on breastfeeding initiation, duration and difficulties in the first four months postpartum. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gaudet L, Ferraro ZM, Wen SW, Walker M. Maternal obesity and occurrence of fetal macrosomia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:640291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hermansson H, Kumar H, Collado MC, Salminen S, Isolauri E, Rautava S. Breast milk microbiota is shaped by mode of delivery and intrapartum antibiotic exposure. Front Nutr. 2019;6:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kuhle S, Tong OS, Woolcott CG. Association between caesarean section and childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16(4):295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Borewicz K, Gu F, Saccenti E, Arts ICW, Penders J, Thijs C, van Leeuwen SS, Lindner C, Nauta A, van Leusen E et al.. Correlating infant faecal microbiota composition and human milk oligosaccharide consumption by microbiota of one-month old breastfed infants. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;e1801214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blanton LV, Charbonneau MR, Salih T, Barratt MJ, Venkatesh S, Ilkaveya O, Subramanian S, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Jorgensen JM et al.. Gut bacteria that prevent growth impairments transmitted by microbiota from malnourished children. Science. 2016;351(6275):aad3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stanislawski MA, Dabelea D, Wagner BD, Iszatt N, Dahl C, Sontag MK, Knight R, Lozupone CA, Eggesbø M. Gut microbiota in the first 2 years of life and the association with body mass index at age 12 in a Norwegian birth cohort. MBio. 2018;9(5):e01751–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cox LM, Yamanishi S, Sohn J, Alekseyenko AV, Leung JM, Cho I, Kim SG, Li H, Gao Z, Mahana D et al.. Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell. 2014;158(4):705–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Han E, Abrams B, Sridhar S, Xu F, Hedderson M. Validity of self-reported pre-pregnancy weight and body mass index classification in an integrated health care delivery system. Paediatr Perinatal Epidemiol. 2016;30(4):314–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sprenger N, Lee LY, De Castro CA, Steenhout P, Thakkar SK. Longitudinal change of selected human milk oligosaccharides and association to infants' growth, an observatory, single center, longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Azad MB, Robertson B, Atakora F, Becker AB, Subbarao B, Moraes TJ, Mandhane PJ, Turvey SE, Lefebvre DL, Sears MR et al.. Human milk oligosaccharide concentrations are associated with multiple fixed and modifiable maternal characteristics, environmental factors, and feeding practices. J Nutr. 2018;148:1733–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vandenplas Y, Berger B, Carnielli VP, Ksiazyk J, Lagström H, Sanchez Luna M, Migacheva N, Mosselmans JM, Picaud JC, Possner M et al.. Human milk oligosaccharides: 2′-fucosyllactose (2′-FL) and lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT) in infant formula. Nutrients. 2018;10(9):E1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.