Introduction

Immediate postpartum long acting reversible contraception (LARC) is an effective and safe strategy to promote maternal health. 1 Nationally, significant efforts are being made to increase access to immediate postpartum (IPP) LARC. 2 However, one unique and vulnerable population has remained excluded from care. Unauthorized and authorized immigrants, within the first five years of residence in the US, are excluded from participation in full scope Medicaid, including postpartum contraceptive services. These immigrants meet the same financial criteria as traditional Medicaid (TM) recipients, but are eligible for Emergency Medicaid (EM) only. EM covers only life threatening injuries or a hospital admission for childbirth.3

Oregon recently covered this population through the Reproductive Health Equity Act (RHEA), which expands reproductive health access, including immediate and interval postpartum contraception.4 Stakeholders needed evidence to demonstrate that immediate postpartum contraception is an acceptable option among immigrant women and that they are able to access removal services when needed..

To address these concerns, we surveyed women who had received IPP LARC through a grant program that preceded RHEA. Grant devices were available to all women who were uninsured for IPP LARC; until 2016, this included all women in our state. To understand the impact of this program for a vulnerable immigrant population, we focused our analyses on Medicaid patients.5 Our primary objective was to assess satisfaction and contraceptive continuation with IPP LARC by Medicaid type.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of women enrolled in Medicaid who received immediate postpartum LARC at OHSU from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2016. We characterized the population by payor type (EM vs TM) and compared contraceptive continuation rates, satisfaction and access to removal services. EM was used as a proxy for both unauthorized or recent immigrant status.3,6

We abstracted demographic and health data (including contraceptive continuation) from the electronic health record and corroborated findings with participant interviews (conducted June 2015-June 2016). Contraceptive continuation and removal rates were obtained from the health record and corroborated by the survey. Information about satisfaction, access to follow-up care and removal services was obtained by the survey only. Women were asked about satisfaction with the care received, method continuation, and access to follow up care, including removal services.

We conducted survival analyses and log-rank test to compare contraceptive continuation rates. All analyses were conducted in Stata 16 (StataCorp LP, College Park Station, Texas). The institutional review board at OHSU reviewed and approved the proposal.

Results

Our sample included 371 women (EM 108, TM 236) who received immediate postpartum IUDs or implants. Overall women receiving IPP LARC had more than two prior births and a significant proportion had medical comorbidities, with no differences noted by payor type.

We successfully contacted a quarter of women (30.1% EM, 21.9% TM n=78) by email, phone or mail, who agreed to complete a follow-up survey. Satisfaction rates were high, and did not differ by Medicaid type or year of placement. Moreover, 81% would recommend immediate postpartum contraception to a friend and 75% said they could make the same decision again, without differences by payor type (p=0.56; p=0.11).

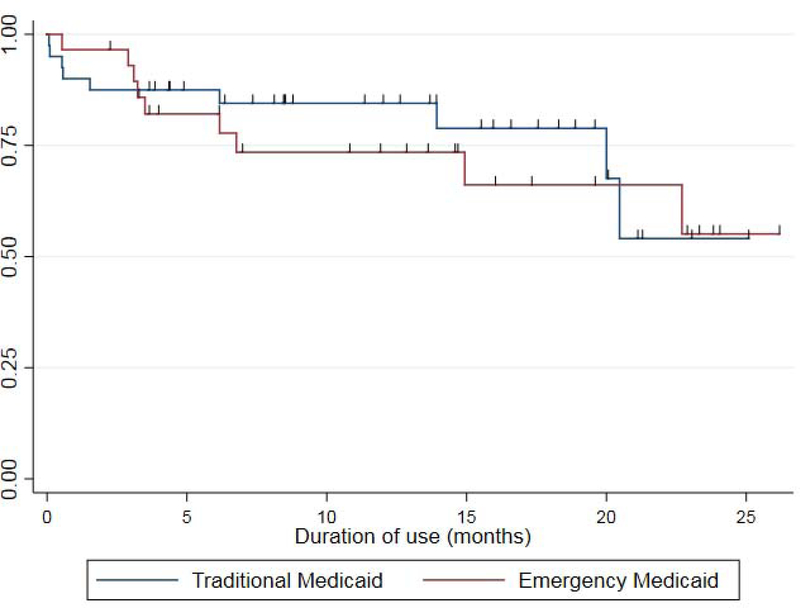

Using our survey and the electronic health record, we determined contraceptive continuation rates for 56% of EM and 61% of TM participants ( n= 204, p=0.23). Survival analysis demonstrated that continuation rates at 12 months were not different by payor type, with 73.5% of EM and 84.5% (p=0.65) of TM enrollees continuing their method (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier graph of time to discontinuation of immediate postpartum long acting, reversible contraception.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve depicting the time to discontinuation of immediate long acting reversible contraception. There was no significant difference (p=0.65) in time method discontinuation by payor type.

Discussion

Our study indicates that immigrant women value the option of immediate postpartum contraception. We demonstrate equivalent contraceptive continuation rates regardless of payor type. Twelve-month continuation among EM recipients is comparable to both TM recipients in our study population, and national rates.7 Importantly, our study finds that women with EM are highly satisfied and suggests that immigrant women are able to access removal services when desired, evidence suggesting that this policy may promote reproductive equity for a vulnerable population.8

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr Rodriguez was a Women’s Reproductive Health Research fellow when the work was conducted; grant 1K12HD085809. Dr. Baldwin is a Women’s Reproductive Health Research Scholar (K12HD085809).

REDcap through OHSU was utilized for this study and as such this research was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1TR0002369. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs Rodriguez and Baldwin have served as contraceptive trainers for Merck. Dr Rodriguez has served on an annual advisory board for Bayer and Cooper Surgical (relationship has ended).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Thiel de Bocanegra H, Chang R, Howell M, Darney P. Interpregnancy intervals: impact of postpartum contraceptive effectiveness and coverage. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:311 e1–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Services CfM. State Medicaid Payment Approaches to Improve Access to Long-Acting Reversible Contraception 2016.

- 3.DuBard CA, Massing MW. Trends in emergency Medicaid expenditures for recent and undocumented immigrants. JAMA 2007;297:1085–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.What is the Reproductive Health Equity Act (HB 3391)? 2017. (Accessed March 7, 2018, at http://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/HEALTHYPEOPLEFAMILIES/REPRODUCTIVESEXUALHEALTH/Pages/reproductive-health-equity-act.aspx.)

- 5.Derose KP, Escarce JJ, Lurie N. Immigrants and health care: sources of vulnerability. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:1258–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Group L MediCal Facts and Figures: a program transforms 2013.

- 7.O’Neil-Callahan M, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Madden T, Secura G. Twenty-four-month continuation of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:1083–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moniz MH, Spector-Bagdady K, Heisler M, Harris LH. Inpatient Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraception: Care That Promotes Reproductive Justice. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:783–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]