Abstract

Extant media literacy interventions have been delivered in person, limiting their potential for large scale reach, implementation, and dissemination. Although emerging evidence suggests the interventions can impact behavior, the theoretical mediators that can explain the efficacy remain unknown. This study investigated the efficacy and mediators of a web-based media literacy intervention for reducing indoor tanning behavior among young women. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: a media literacy intervention with counter argument production, a media literacy intervention with counter story production, or an assessment-only control condition. The outcomes of indoor tanning behavior and intention were evaluated with 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Results indicated significant effects of the web-based intervention on reducing indoor tanning behavior at the follow-ups. Changes in perceived media realism completely mediated the intervention effects on behavior. Perceived media realism, positive and negative outcome expectancies, and collective efficacy partially mediated intervention effects on intention. This study demonstrates the efficacy of a web-based media literacy intervention and the theoretical mechanisms underlying the efficacy. It indicates that by altering perceived media realism, outcome expectancies, and collective efficacy, web-based media literacy interventions could generate behavioral effects.

The media frequently show positive outcomes rather than negative consequences of risk behavior (Dalton et al., 2002) and exposure to those portrayals leads to engagement in the risk behaviors such as alcohol and tobacco use (Dalton et al., 2003; Willis, Sargent, Gibbons, Gerrard, & Stoolmiller, 2009). Another area where media exposure and risk behavior are linked is indoor tanning (IT). Research has found media use is significantly associated with IT behavior among women aged 18–25 (e.g., Stapleton, Hillhouse, Coups, & Pagoto, 2016), a group that has reported higher rates IT than any other population groups (U.S. Centers for Disease Control, 2010). As IT increases the risk of melanoma (El Ghissassi et al., 2009), the fifth most prevalent cancer in the United States (Siegel, Miller, & Jemal, 2018), identifying effective intervention strategies for reducing IT behavior among young women is a public health priority (CDC, 2010).

Media literacy interventions (MLIs) are preventative programs designed to provide people with the knowledge to recognize the media’s influences on their health-related decisions and actions and the skills to combat the unhealthy media effects (Aufderheide, 1993). Because appearance enhancement is one of the motivations for IT behavior (Hillhouse, Turrisi, Stapleton, & Robinson, 2008) and the media are a primary source of information about beauty and style for young women (Harrison & Hefner, 2011), MLIs can be an efficacious approach for reducing their IT practices.

To date, the overwhelming majority of MLIs have been delivered in-person. Face to face interventions through in-person delivery may facilitate greater rapport with participants, thereby generating greater efficacy. They are, however, resource intensive and costly, limiting the potential of the interventions for large scale reach, implementation, and dissemination. Research has found MLIs are persuasive in impacting attitudes and intentions across various domains of health (Jeong, Cho, & Hwang, 2012). Moreover, a recent field-delivered MLI demonstrated efficacy in reducing indoor tanning behavior assessed at a six-month follow-up (Cho, Yu, Cannon, & Zhu, 2018). It remains unknown, however, how MLIs impact behavior.

To address this gap in knowledge, this study investigates efficacy and mediators of a web-based MLI designed to reduce IT practices among young women. This web-based MLI adapted the field-based MLI of Cho et al. (2018). In this study, we seek to extend prior research in the following ways. First, we examine whether the behavioral effects observed with in-person delivery is replicated with web-delivery. Second, we investigate mediators that account for the behavioral effects of the web-based intervention. Third, a process evaluation of the web-based intervention is conducted. Finally, we use a different sample in this study. Whereas the field-based intervention was delivered to sorority houses and conducted in small-group settings, this web-based intervention involves individual young women.

Conceptual Bases

As MLIs are an approach to addressing problematic media effects on individuals and society, their two main goals are to help individuals become critical consumers of the media and to enable them to become creators of conscious voices against predominant media messages (Aufderheide, 1993). MLIs, therefore, have frequently been comprised of two main modules, media analysis and media production. In the media analysis modules, participants analyze the content and functions of the media influencing risk behavior-related attitudes. In the media production module, participants create counter messages in a variety of forms to help themselves and peers resist harmful media influence.

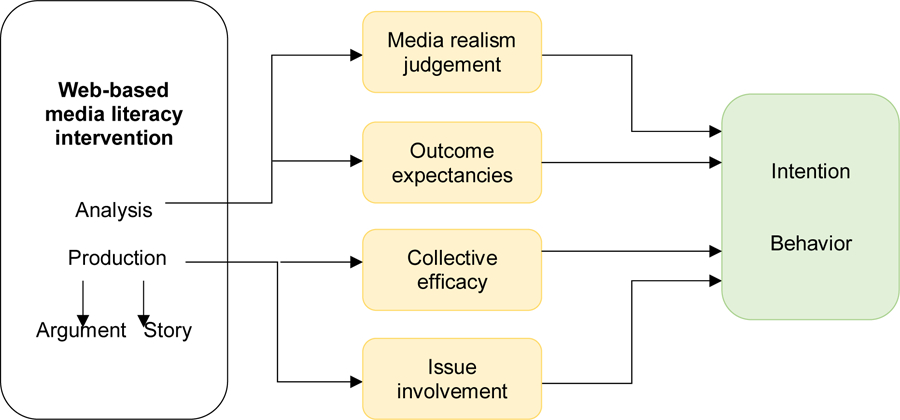

Based on the review of existing media literacy frameworks and perspective (Austin & Johnson, 1997; Botta, 1999; Culver, 1999; Hobbs & Frost, 2003; Primack, Sidani, Carroll, & Fine, 2009; Thoman & Jolls, 2005) and integrating it with other perspectives and recent research findings, this study postulates four main theoretical mediators of MLI effects: perceived media realism, behavioral outcome expectancy, collective efficacy, and issue involvement. It further posits that perceived media realism and behavioral outcome expectancy are aligned with the media analysis module and that issue involvement and collective efficacy are associated with the media production module (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework

Perceived media realism, a core construct in media effects research, refers to the degree to which individuals deem media content reflects reality (see for dimensions and measures Cho, Shen, & Wilson, 2014). Media literacy education provides individuals with high critical consciousness of media content and effects. With abilities to analyze and evaluate media content and effects, individuals are more likely to discern the deviation between the media world and the real world (Austin & Johnson, 1997; Botta, 1999; Hobbs & Frost, 2003; Primack et al., 2009; Thoman & Jolls, 2005). The realization of the disparity between the media and the actual reality may then result in lowering of perceived media realism. Changes in perceived media realism could be a motivation to alter a previously media-influenced attitude toward risk behavior to the direction consistent with the actual reality.

Whereas perceived media realism concerns the contrast between media world and social reality, outcome expectancy focuses on beliefs about the positive and negative results to be obtained by engaging in a behavior. Formed by observing the social world, outcome expectancy influences behavioral decisions (Bandura, 1986). Important in the social world are the media, which often portray positive aspects of performing a risk behavior, such as tanned celebrities enjoying fame and popularity. Therefore, the media play an important role in informing outcome expectancy. Taken together, when individuals realize media depictions do not correspond with the actual reality, they may begin to question their previously held positive outcome beliefs and to form or strengthen negative outcome beliefs.

Collective efficacy and issue involvement can be central to media production, in which individuals develop counter messages to help themselves and others in society resist harmful media messages. The media frequently shape beliefs about society (Gerbner, 1990), such as social norms, which in turn influence behaviors. Helping individuals counter social norms may require fostering collective efficacy. One of the fundamental forms of human agency motivating and guiding action, collective efficacy refers to the belief in one’s group’s ability to carry out a given course of behavior to accomplish a desired outcome (Bandura, 2000; Fernandez-Ballesteros et al., 2002). A source of collective efficacy beliefs is the enactment of a similar behavior (Bandura, 1986, 2000). Because message production is an action to persuade the self and others to be aware of unhealthy media messages, refute them, and change behavior for health, MLIs including media production may promote collective efficacy beliefs.

Issue involvement refers to perceived personal relevance of a topic (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). The exercise of media production is likely to foster attention to and interest in not only the message under construction but also the issue the message represents. Research has found individuals with high involvement actively process issue-related information, scrutinize the information for validity, and maintain strong attitude toward the issue (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Issue involvement formed through media production experience may help individuals resist post-intervention exposure to pro-tanning media messages and maintain negative attitude toward IT shaped through the MLI.

Argument and Story Production

Media literacy is not only the abilities to analyze the media but also to produce counter messages (Aufderheide, 1993). Past research has found the inclusion of media production increased the persuasiveness of MLIs rather than media analysis alone (Banerjee & Greene, 2007). Research, however, has not investigated which type of message production could be more effective. As media and communication technologies are increasingly enabling users of the media to become creators of content, examining the kinds of messages that are more efficacious in promoting behavior change is important. Two perspectives pertinent to media production are self-persuasion (Aaronson, 1999) and expressive writing (Pennebaker, 1997). Research on self-persuasion has focused on the effects of self-generated arguments, and studies on expressive writing are more aligned with stories as they have examined the therapeutic effects of describing an emotional past event.

Creation of arguments and stories may utilize differential psychological mechanisms. Argument production may principally be cognitive work, while story production may be an emotional endeavor. Arguments are a product of logic, and the generation of arguments requires scrutiny, analysis, and synthesis of information (Brinol, McCaslin, & Petty, 2012). Storytelling, on the other hand, requires individuals to go inside self to revisit the past and reflect on their personal experience and associated feelings to recount it (Larkey & Hill, 2012). Cognitive and emotional engagement in message production, in turn, may increase issue involvement differentially. Although in earlier research cognitive engagement was primarily associated with issue involvement (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), recent research demonstrates emotional engagement can lead to attention and interest in the processing of a given narrative message and change in the attitude toward the issue portrayed in the narrative (Slater, Rouner, & Long, 2006).

Hypotheses

Based on the preceding discussion, we expected young women who participated in either of the MLI conditions would report less IT behavior and intention than those who participated in the control condition. These effects would be mediated by media realism, outcome efficacies, collective efficacy, and issue involvement. Moreover, we expected young women who participated in the MLI with story production would report less IT behavior and intention than those who participated in the MLI with argument production. This expected difference would be through differential engagement in the message production such that women in the argument production would report greater cognitive engagement, while those in the story production would report greater emotional engagement. Cognitive and emotional engagement, in turn, would differentially lead to issue involvement.

Methods

Design

A three-arm randomized controlled design evaluated the efficacy of a web-based MLI. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: a media literacy with argument production condition, media literacy with story production condition, and assessment only control condition. The study was designed to capture the seasonal nature of IT which peaks in January through March (Abar et al., 2010). Baseline assessment was conducted in September, the intervention was delivered in October, and two follow-up assessments were done 3 months post in January and 6 months post in April.

Participants

Participants were college women (N = 518) attending a large public university in U.S. Midwest, a region where IT is prevalent (Demko et al., 2003). Their age ranged from 18 to 24 (M = 20.13, SD = 1.29) The majority of them (89.6%) were White, and the rest were comprised of Asian (4.1%), other (2.9%), and Hispanic or Latino (2.7%). Participants were recruited from a list of computer-generated, randomly selected female students aged 18 to 25 at the university. Consistent with prior research (Hillhouse et al, 2008), the inclusion criteria were having indoor tanned 1 ≥ times in the past 12 months or having 5 ≥ intention to indoor tan in the next 12 months on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 “very unlikely” to 7 “very likely.” Retention was 78% at 6 months. The university IRB approved the study protocol.

The Intervention

As indicated above, this web-based intervention adapted the content of a previously developed and evaluated MLI (Cho et al., 2018). Because the prior intervention was delivered in-person in the field at sorority houses, the format was transformed to fit the web platform. Whereas the prior study relied on interventionists’ written script- and protocol-based delivery each time, a voice over was recorded for each page in this web-based intervention. The content, including visual images, anecdotes, and research evidence was updated and modified as well. The role of social media, including Instagram, was addressed. This intervention comprised of five sections. The first four sections were for media analysis and the fifth was for media production. The first four sections were identical between the two intervention conditions. Appendix A presents the focal content of the media analysis sections. The final Action section was devoted to either counter argument or story production. Participants first were given a brief instruction, followed by an example of either counter argument or story. After being asked to provide feedback on the sample counter message, participants were asked to design their own counter message and then upload it to the web platform.

Process Evaluation

The web-based MLI was 38.02 minutes long, with the first four media analysis sections 32.41 and the fifth and final media production section 5.60 minutes long in instruction. A median of 35.75 minutes was spent by participants. After each of the four media analysis sections, participants were asked to write about what they took away from the section in a comment box. Across the sections, an average of 96.75% of participants commented, and the average number of words in the comments was 40.97. After completing the first four sections, they rated the program on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree in terms of clarity (M = 4.52, SD = .64), information value (M = 4.13, SD = .71), interest value (M = 4.16, SD = .64), and persuasiveness (M = 4.16, SD = .75). Overall, 70.11% of participants across the two conditions produced a counter message. Those who produced a message spent a median of 12.24 minutes in the section, while those who did not spent a median of 2.21 minutes. In the argument condition, 66.18% of the participants produced a message. In the story condition, 74.07% produced it.

Measures

The primary and secondary outcomes of the MLI were IT behavior and intention measured at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Theoretical mediators, media realism, outcome expectancies, collective efficacy, and issue involvement were measured at 6 months. When validated scales were not available, items reflecting underlying construct content were developed. Response scales for the mediator variables ranged from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree.”

Indoor tanning behavior was measured with the scale recommended by National Cancer Institute (Lazovich et al., 2008). The accuracy of the scale has also been demonstrated (Hillhouse et al., 2012). The scale assessed monthly IT behavior.

Indoor tanning intention was measured by asking participants to indicate the likelihood they will use an IT bed/booth in the next month on a five-point scale ranging from “very unlikely” to “very likely.”

Media realism was measured with four items including: “Media representations of tanned looks are truthful” and “The media shows the entire truth about tanned looks.” A principle axis factor analysis using varimax rotation yielded a single factor solution (α = .85).

Outcome expectancies were measured with items adopted from the comprehensive IT expectancy scale (Noar, Myrick, Morales-Pico, & Thomas, 2014). Positive (appearance benefits, convenience, mood enhancement) and negative expectancies (appearance harm, health threat, physical/psychological discomfort) associated with IT were distinguished. Each valence was measured with nine items (positive α = .89; negative α = .81).

Collective efficacy was measured with two items: “Young women can take collaborative actions against pro-tanning social norms” and “Young women can work together to combat harmful media influences on them” (α = .78).

Issue involvement was measured with two items: “I’ve thought about the issue of melanoma” and “The issue of melanoma has been on my mind” (α = .84).

Cognitive engagement in message production was measured at immediate posttest with two items: “It was thought-provoking to develop the counter message” and “I gave a lot of thoughts into the design of the counter message” (α = .83).

Emotional engagement in message production was measured at immediate posttest with two items: “I was emotionally involved in developing the counter message” and “Designing counter messages had an impact on my emotions” (α = .92).

Demographic variables included age, race/ethnicity, and skin sensitivity (Weinstock, 1992). Covariates included past behavior and future intention at baseline. Participants reported the number of times they indoor tanned in each of the preceding eight months (August – January) on a five-point scale ranging from zero to four or more times. Participants estimated their IT likelihood in the next 12 months on a scale ranging from 1 “very unlikely to 7 “very likely.”

Results

Analysis Strategy

Analysis was conducted using statistical software R 3.5.0, and packages lme4 and glmmTMB for the generalized linear mixed model fitting. A restricted maximum likelihood method was used to estimate parameters and standard errors using all available information from partially missing cases, which were less than 10% of the total data. Specifically, there were 9.6% cases missing some data, with 6.0% and 6.2% missing in the follow-up assessments of behavior and intention. Mixed effect models were employed for unbiased estimation.

Baseline Analyses

We use an analysis of variance model to assess the baseline distribution of behavior and intention across the three conditions. The means and standard deviations of the sum of the past eight months’ IT behavior were 18.69 (9.16), 18.98 (10.08) and 18.56 (8.76) in argument, story, and control conditions. The difference across the three conditions was not significant (F = .09, p = .91). The means and standard deviations of future IT intention were 5.28 (1.44), 5.13 (1.66) and 5.26 (1.56) in the argument, story, and control conditions. The difference was not significant (F = .50, p = .61).

Behavior

We assessed the occurrence of the IT behavior in the follow-up months using a mixed-effect logistic regression model. We employed this approach because the data were inconsistent with the assumptions of a Poisson or a negative binomial distribution. Similar to the Cho et al. (2018) sample comprised of sorority women, this sample of college women reported two primary responses at the follow-ups: A substantial number of participants reported zero IT behavior, while a subgroup reported ten or more times IT per month. Therefore, consistent with Cho et al. (2018), we transformed the number of occurrences of IT behavior to a binary response, where 1 indicated the occurrence of IT and 0 indicated no IT. This contrast was used to reflect these subgroups to focus on predicting whether a participant did or did not indoor tan. A positive point biserial correlation between the binary indicator and IT frequency (r = .65, p < .001) justifies this transformation.

In the logistic model, we modeled the association between the responses of the same participant using a random intercept for each participant assuming it follows a normal distribution. We treated the months as a fixed effect. Baseline intention and behavior were adjusted for. The model specification was:

where stood for intervention condition, for month, for participant, ’s baseline intercept and fixed effects for the baseline intention and behavior, fixed effect for intervention condition , fixed effect for month , and random effect for participant in condition .

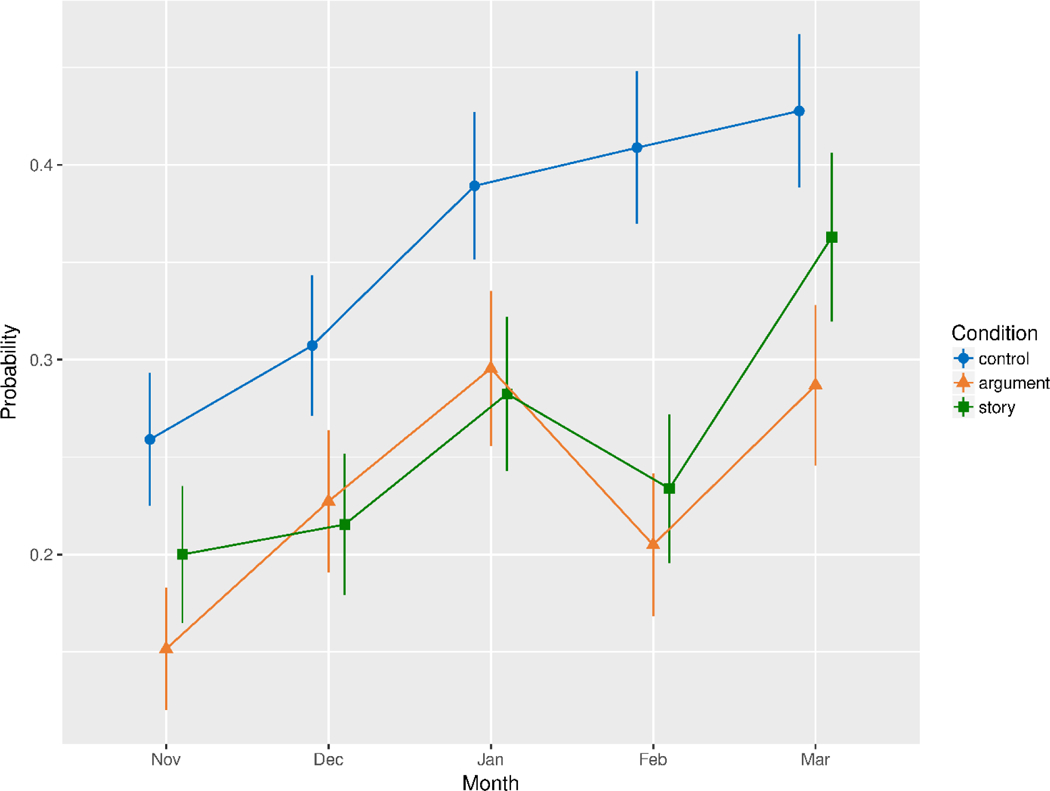

A significant difference among the three groups was observed (likelihood ratio test statistics = 13.67, p = .001). Participants in the intervention groups were less likely to be indoor tanners compared to those in the control group at the two follow-up assessments. The baseline intention (Wald test = 3.73, p < .001) and behavior ( = 75.58, p < .001) were positively associated with IT behavior. A significant difference across the months was also detected ( = 57.94, p < .001). To further examine the differences among the three conditions, we performed pairwise comparisons (Details in Table 1). The odds of reporting as a non-IT user were 3.42 (p < .001) and 2.01 (p = .036) times less for the argument and story group participants, respectively, compared to the odds of control group participants. We plotted the probability and the standard error of IT usage for each condition over the follow-up months in Figure 2, which shows the intervention buffered the seasonal increase in IT. Although an increasing trend across the follow-up period was observed in all groups, the intervention participants reported lower probabilities than the control participants.

Table 1.

Effects of the Intervention on Behavior and Intention: Comparisons between Conditions

| Estimate | Standard error | Z | p | Adjusted p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT behavior | |||||

| Argument vs. control | −1.2283 | .3415 | −3.60 | .0003 | .0009 |

| Story vs. control | −.6963 | .3325 | −2.09 | .0362 | .0910 |

| Argument vs. story | −.5320 | 0.3611 | −1.47 | .1408 | .3037 |

| IT intention | |||||

| Argument vs. control | −.3596 | .0944 | −3.81 | .0002 | .0005 |

| Story vs. control | −.4069 | .0942 | −4.32 | .0000 | .0001 |

| Argument vs. story | .0474 | .0996 | .48 | .3175 | .8830 |

Note. Adjusted p values were calculated using Tukey’s method for multiple comparison between conditions.

Figure 2.

Probability of IT behavior at follow-up assessments

Intention

We assessed the intervention effect on IT intention using a mixed-effect linear regression model. The response variable was the intention to use IT at the two follow-ups. Because the intention of the same participant was correlated and the responses from the same follow-up wave for each participant were also correlated, we treated the participant and wave within participant as random effects. The model specification was:

where stood for intervention condition, for month, for participant, for wave, ’s baseline intercept and fixed effects for the baseline intention and behavior, fixed effect for intervention condition , fixed effect for month , random effect for participant in condition , random effect for wave of participant in condition , and random error.

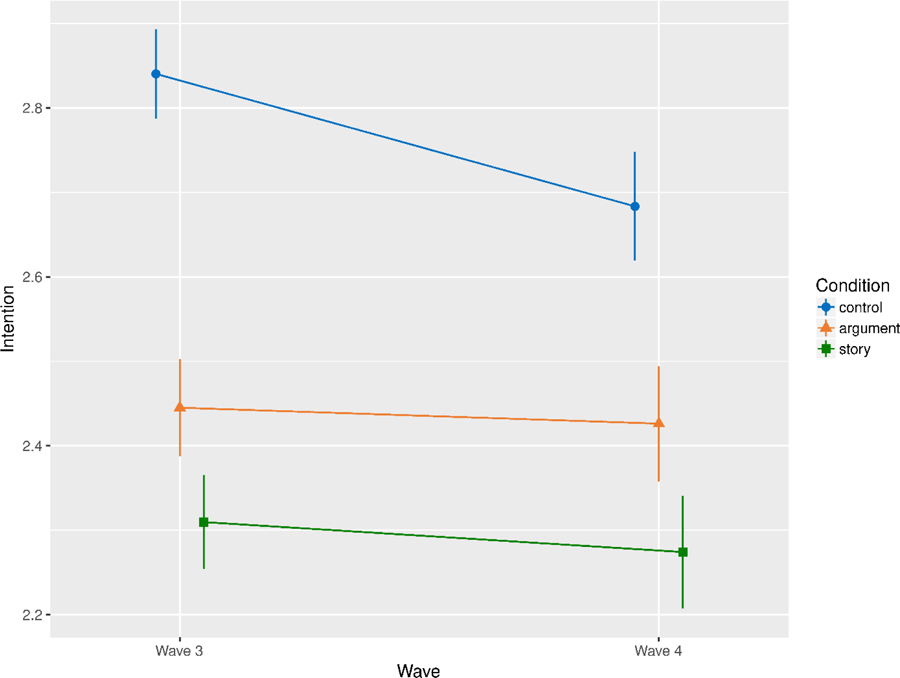

A significant difference among the groups was observed ( = 11.57, p < .001). The baseline intention ( = 53.03, p < .001) and behavior ( = 14.96, p < .001) were positively associated with IT intention. To further examine the differences among the three conditions, we performed pairwise comparisons (details in Table 1). We found significant differences between argument and control (p < .001), and between story and control (p < .001). No significant difference between argument and story groups was found. Participants in the argument and story groups indicated weaker intentions to IT in the next months than those in the control group across the two follow-ups. Figure 3 depicts the time trends for the two waves. Across the waves, intervention participants reported weaker IT intention than control participants.

Figure 3.

IT intention at follow-up assessments

Mediators

We first examined the effects of the intervention on the theoretical mediators. An analysis of variance model was performed to compare the three groups. Then pairwise comparisons were performed between each pair of groups, using t-tests with Tukey’s p value adjustment for multiple comparisons. As shown in Table 2, there were significant differences between the intervention conditions and the control condition for media realism and positive and negative outcome expectancies. Significant differences between argument condition and control condition were also found for collective efficacy and issue involvement.

Table 2.

Comparison of Intervention Effects on Theoretical Mediators across the Conditions at 6-month Follow-up

| Media realism | Expectancy (positive) | Expectancy (negative) | Collective efficacy | Issue involvement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argument | 1.99a (1.12) | 3.88a (1.26) | 5.58a (0.91) | 5.55a (0.97) | 4.86a (1.52) |

| Story | 2.15b (1.14) | 3.71b (1.12) | 5.59b (0.88) | 5.45 (1.07) | 4.56 (1.46) |

| Control | 3.24ab (1.14) | 4.67ab (0.85) | 4.97ab (0.86) | 5.22a (1.13) | 4.37a (1.65) |

Notes. Numbers are means and standard deviations. Means sharing the same subscripts are significantly different at Tukey adjusted p < .05.

To further examine mediation effects, we adopted the approach described by Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, 2010), which requires fitting the model to examine the association between (1) causal variable and mediator, (2) mediator and response conditional on causal variable, and (3) causal variable and response conditional on mediator. As a modification of the Baron and Kenny (1986) approach, the Zhao et al. approach does not require a significant total effect and it does not claim the existence of direct effect even if (3) is significant. It should be noted because our causal variable is the treatment condition with three groups, there will be two effect coefficients for the model (1) and (3). Additionally, because our outcome variable is a longitudinal measurement, the current method that jointly tests the product of the coefficients in (1) and (2) cannot be easily extended to our study. Therefore, we examined the three conditions based on the significance of the corresponding statistical test. A mediation effect exists if both (1) and (2) are significant. A complete mediation effect is present if (3) is not significant.

To examine condition (1), we used linear models to regress mediators on intervention condition controlling for baseline behavior and intention. For conditions (2) and (3), we used mixed-effect models similar to our previous analysis by adding the mediators to the model. For the causal variable which is multiple categorical in nature, two dummy variables were created for the argument and story conditions, with the control as reference group. The significance of the categorical variable was calculated using likelihood ratio tests and F-tests. Wald tests were also performed on the coefficients of the dummy variables to test the difference between the two interventions groups and the control group. The testing p values for conditions (1)-(3) are listed in Table 3. Media realism completely mediated intervention effects on IT behavior. For IT intention, outcome expectancies (both positive and negative), media realism, and collective efficacy were partial mediators. Adjusting for these four partial mediators would not eliminate the correlation (p = .029) between intervention condition and IT intention, which means collectively they do not completely mediate the intervention effect on IT intention. Issue involvement was not a mediator for either IT behavior or intention.

Table 3.

Tests of Indirect Effects of the Intervention on Behavior and Intention at 6-month Follow-up

| Intervention -> Mediator | Mediator -> behavior | Mediator -> intention | Intervention -> behavior | Intervention -> intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media realism | −1.25*** | .49*** | .10** | −.61† | −.24* |

| −1.07*** | −.19 | −.31** | |||

| Outcome expectancy (positive) | −.79*** | .11 | .11** | −1.14** | −.27** |

| −.92*** | −.60† | −.31** | |||

| Outcome expectancy (negative) | .63*** | −.05 | −.08 | −1.19*** | −.31** |

| .60*** | −.67† | −.36*** | |||

| Collective efficacy | .33* | −.22† | −.14*** | −1.24*** | −.33*** |

| .21† | −.70* | −.38*** | |||

| Issue involvement | .52** | −.02 | −.04† | −1.30*** | −.36*** |

| .21 | −.75* | −.40*** |

Notes. Numbers are unstandardized linear regression coefficients. In the intervention -> mediator and intervention -> outcome (behavior, intention) columns, the first row is for argument and the second row is for story.

p < .1

p < .05

p < .01

p ≤ .001

Argument vs. Story

Finally, we examined the process of argument and story condition effects on cognitive and emotional engagement in message production, and then these differential types of engagement effects on issue involvement at six months. To evaluate the effects of the argument and story condition on cognitive and emotional engagement, we regressed the two engagement types on the intervention conditions, controlling for the baseline behavior and intention. For cognitive engagement in message production, no significant difference between the two conditions was found: adjusted Ms = 4.82 and 4.90, p = .67. For emotional engagement in message production, a significant difference between the argument and story groups was found: adjusted Ms = 4.08 and 4.61, p = .01. Story group participants reported a higher-level emotional engagement in message production than argument group participants.

Next, to evaluate the effects of the cognitive and emotional engagement in message production at immediate post on issue involvement at six months, we regressed issue involvement on cognitive and emotional engagement, adjusting for the intervention conditions and baseline behavior and intention. No significant effect of cognitive engagement on issue involvement was found: β = −.002, p = .99, but a significant effect of emotional engagement on issue involvement was found: β = .24, p = .006. An F-test, however, showed the difference of the two effects was not significant (p = .15).

Discussion

The results demonstrate the web-based MLI was efficacious in reducing IT practices. Young women who were in either of the intervention conditions reported lower IT than those who were in the control condition, and women who were in the intervention conditions reported weaker IT intention. These results are congruent with those obtained from the field-based MLI delivered face to face at sorority houses.

The results, furthermore, indicate the efficacy of the web-based MLI was mediated by changes in media realism, positive and negative outcome expectancies, and collective efficacy. Of note, media realism completely mediated the long-term behavioral efficacy and partially mediated intention at six months. These results indicate the centrality of correcting perceived media realism in MLIs for behavior change. Correcting media realism involves creating awareness of media content concerning a risk behavior, demonstrating the contrast between the outcomes of the risk behavior in the media world and actual world, and reflecting on the effects of the media content on the beliefs and behaviors of self and society. Future efforts to address media realism perceptions should consider aspects of the perceptions new and unique to new media (see Cho, Li, Shen, & Cannon., 2019).

In addition to media realism, outcome expectancy beliefs were significant partial mediators of the behavioral intention at six months. Together, the results suggest future MLIs for risk behavior reduction can focus on altering the media realism and outcome beliefs of the population, through critical analysis and evaluation of media content.

A novel aspect of this study was its ability to foster collective efficacy, which also partially mediated intervention effects on intention. As predominant media messages could influence social normative perceptions, collective efficacy can be important to combating them. This study used the participative module of counter message production to generate collective efficacy and issue involvement so that young women can become not only critical consumers of the media but also creators of alternative voices and agents for social change.

Although data were consistent with the expectation for collective efficacy, they were not for issue involvement. As predicted, story production increased emotional engagement, which, in turn, influenced issue involvement. However, issue involvement was not associated with either behavior or intention at six months. Although the intervention significantly reduced IT behavior, there was no difference between the argument and story production conditions.

These findings may suggest the current public discourse about the potential power of storytelling for self-behavior change may need to be reconsidered. This study, along with Cho et al. (2018) in which sorority member women produced counter messages in small groups using iPads, obtained no evidence supporting the presumed advantage of stories in generating behavioral impact (see also Krause & Rucker, 2019). Instead, the results suggest argument production can be as impactful as story production. This is despite story production significantly influenced emotional engagement in message production. Emotional engagement in story production, however, appears to have a limited role in motivating self-behavior change.

Storytelling is frequently a recount of past experiences. The discrepancy between present awareness and past actions may evoke dejection emotions such as dissatisfaction, disappointment, or sadness (Higgins, 1987). Argument production, on the other hand, may require scrutinizing the external environment which may lead to efforts to cope with problems detected in the environment (Bless, Mackie, Schwarz, 1992). Future research should closely examine the more fine-grained psychological pathways through which argument and story production may generate effects. For example, research could measure the specific thoughts and emotions elicited during message production and use the though-listing technique to investigate the cognitions elicited during message production. Such efforts will be important because little knowledge has been available to explain the mechanisms underlying differential forms of participative actions. The argument and story production examined in this study are only two of the forms of participatory actions increasingly feasible through new media platforms.

Moreover, it is noteworthy the intervention was rather brief, about 40 minutes long in instruction, but could impact behavior at six months. Moreover, over 70% of participants chose to produce a counter message. These results show brief MLIs with strong conceptual bases could exert strong impact on behavior. A next step in this research may be to examine the role of the engagement factors in influencing the long-term efficacy.

This study’s limitations include the fact it was conducted with college women. Although research has indicated college women are a high-risk group with respect to IT (e.g., Mays & Evans, 2017), future research should examine the efficacy of the intervention with a more socioeconomically diverse sample. In addition, there might have been a measurement issue with issue involvement. In this study, the measurement focused on indoor tanning and melanoma. It is possible the intervention impacted participants’ involvement in the issue of media representations of tanned looks. Future research should improve the measurement so that the understanding of the role of issue involvement can be enhanced.

In sum, this study adds to knowledge by demonstrating the efficacy of a web-based MLI and the mediators underlying the efficacy. It indicates that by altering perceived media realism, outcome expectancies, and collective efficacy, web-based MLIs could generate behavior change.

Appendix A. Focal Content of Media Analysis Sections

| Section | Focus |

|---|---|

| Media and Women | Historical overview of media influences on women’s health-related perceptions and behaviors |

| Two Tales of Carcinogens | Contrasted that the carcinogen of tobacco smoke is readily visible, but the carcinogen of UV rays from is not; therefore, media influences on indoor tanning can be subtle |

| Feminine Mystiques | Named after Friedan’s 1963 book, this section presented changing ideals of women’s bodies facilitated by the media and advocated women to be true to their self and embrace their natural skin tone. |

| Voice of Women | Presented everyday women who have spoken against the harms of indoor tanning and melanoma |

Contributor Information

Hyunyi Cho, School of Communication, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH.

Chi (Chuck) Song, Division of Biostatistics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH.

Dinah Adams, Futurety LLC, Columbus, OH.

References

- Abar BW, Turrisi R, Hillhouse J, Loken E, Stapleton J, & Gunn H (2010). Preventing skin cancer in college females. Health Psychology, 29, 574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson E (1999). The power of self-persuasion. American Psychologist, 54, 875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Aufderheide P (1993). Media literacy: A report of the national leadership conference on media literacy. Aspen, CO: Aspen Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, & Johnson KK (1997). Effects of general and alcohol-specific media literacy training on children’s decision making about alcohol. Journal of Health Communication, 2, 17–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee SC, & Greene K (2007). Antismoking initiatives: Effects of analysis versus production media literacy interventions on smoking-related attitude, norm, and behavioral intention. Health Communication, 22, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2000). Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bless H, Mackie DM, & Schwarz N (1992). Mood effects on attitude judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 585–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta R (1999). Television images and adolescent girls’ body image disturbance. Journal of Communication, 49, 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Briñol P, McCaslin MJ, & Petty RE (2012). Self-generated persuasion: Effects of the target and direction of arguments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 925–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Li W, Shen L, & Cannon J (2019). Social media and attitude toward e-cigarette use among adolescents: Motivations, mediators and moderators. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21, e14303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Shen L, & Wilson KM (2014). Perceived realism: Dimensions and roles in narrative persuasion. Communication Research, 41, 828–851. [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Yu B, Cannon J, & Zhu YM (2018). Efficacy of a media literacy intervention for indoor tanning prevention. Journal of Health Communication, 23, 643–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver SH (1999). The television and video survival guide. Asheville, NC: Brown Dog Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Tickle JJ, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Ahrens MB, & Heatherton TF (2002). The incidence and context of tobacco use in popular movies from 1988 to 1997. Preventive Medicine, 34, 516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Titus-Ernstoff L, Gibson JJ, Ahrens MB, … Heatherton TF (2003). Effects of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: A cohort study. Lancet, 362 (9380), 281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demko CA, Borawski EA, Debanne SM, Cooper KD, & Stange KC (2003). Use of indoor tanning facilities by white adolescents in the United States. Archives Pediatric Dermatology, 157, 854–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Ghissassi F, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, Bouvard V …Cogliano V (2009). A review of human carcinogens part D: Radiation. Lancet Oncol, 10, 751–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbner G (1990). Epilogue: Advancing the path of righteousness (maybe) In Signorielli N, & Morgan M (Eds.), Cultivation analysis: New directions in media effects research (pp. 249–262). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ballesteros R, Díez-Nicolás J, Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, & Bandura A (2002). Structural relation of perceived personal efficacy to perceived collective efficacy. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51, 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison K, & Hefner V (2011). Media, body image, and eating disorders In Calvert SL & Wilson BJ (Eds.), The handbook of children, media, and development (pp. 381–406). Malden, MA: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94, 319–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Jaccard J, & Robinson J (2012). Accuracy of self-reported sun exposure and sun protection behavior. Prevention Science, 13, 519–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Scaglione NM, Cleveland MJ, Baker K, & Florence C (2017). A web-based intervention to reduce indoor tanning motivations in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science, 18, 131–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Stapleton J, & Robinson JA (2008). A randomized controlled trial of an appearance focused intervention to prevent skin cancer. Cancer, 113, 3257–3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs R, & Frost R (2003). Measuring the acquisition of media-literacy skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 38, 330–355. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S, Cho H, & Hwang Y (2012). Media literacy interventions: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Communication, 67, 454–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause RJ, & Rucker DD (2019, Epub ahead of print). Strategic storytelling: When narratives help versus hurt the persuasive power of facts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkey LK, & Hill A (2012). Using narratives to promote health In Cho H (Ed.), Health communication message design (pp. 95–112). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lazovich D, Stryker JE, Mayer JA, Hillhouse J, Dennis LK, Pichon L, … Thompson K (2008). Measuring nonsolar tanning behavior: Indoor tanning and sunless tanning. Archives of Dermatology, 144, 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays D, & Evans WD (2017). The effects of gain-, loss-, and balanced-framed messages for preventing indoor tanning among young adult women. Journal of Health Communication, 22, 604–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Myrick JG, Morales-Pico B, & Thomas NE (2014). Development and validation of the comprehensive indoor tanning expectations scale. JAMA Dermatology, 150, 512–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8, 162–613-619. [Google Scholar]

- Petty R, & Cacioppo J (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Sidani J, Carroll MV, & Fine MJ (2009). Associations between smoking and media literacy in college students. Journal of Health Communication, 14, 541–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, & Jemal A (2018). Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68, 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD, Rouner D, & Long MA (2006). Television dramas and support for controversial public policies. Journal of Communication, 56, 235–252. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton JL, Hillhouse J, Coups EJ, & Pagoto S (2016). Social media use and indoor tanning among a national sample of young adult non-Hispanic white women: A cross-sectional study. Journal of American Academy of Dermatology, 75, 218–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoman E, & Jolls T (2005). Media Lit Kit—Literacy for the 21st Century: An overview and orientation guide to media literacy education. Retrieved from: http://www.medialit.org/sites/default/files/01_MLKorientation.pdf

- Weinstock MA (1992). Assessment of sun sensitivity by questionnaire: Validity of items and formulation of a prediction rule. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 45, 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis TA, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, & Stoolmiller M (2009). Movie exposure to alcohol cue and adolescent alcohol problems: A longitudinal analysis in a national sample. Psychology of Addictive Behavior, 23, 23–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Lynch JG, & Chen Q (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar]