Abstract

Background

Reflux symptoms including various extra-esophageal manifestations are commonly reported after esophagectomy. However, the intensity and presentation of reflux are both diverse and variable by patients. In this study we assessed reflux symptoms using the reflux symptom index (RSI) questionnaire in patients who underwent esophagectomy for esophageal cancer to order to identify the prevalence of significant reflux and its risk factors.

Methods

From April 2017 to July 2017, we investigated patients who underwent esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. The severity of reflux was evaluated with a self-administered nine-item outcomes instrument (score: 0 to 5). An RSI score ≥13 was considered significant reflux. Multivariable analysis was conducted to identify risk factors.

Results

A total of 151 patients was included (mean age, 64.1±8.8 years; male, n=136, 90.1%). The median time after esophagectomy was 22.6 months. The question regarding heartburn, chest pain, indigestion, or acid coming up was most frequently responded (n=104, 68.9%) with 41 (27.2%) patients presenting significant reflux (mean RSI score, 19.9±6.3). Time after esophagectomy <2 years, vocal cord palsy, retrosternal route of reconstruction, and postoperative weight loss were identified as significant risk factors for RSI ≥13 in the multi-variable analysis.

Conclusions

Reflux related symptoms including extra-esophageal manifestations were common. Our study revealed that short duration after esophagectomy, vocal cord palsy, retrosternal route of reconstruction, and postoperative weight loss were significant associated factors for reflux symptom after esophagectomy.

Keywords: Esophageal reflux, esophageal surgery, esophageal cancer

Introduction

Esophagectomy is a standard treatment for resectable esophageal cancer. Although postoperative mortality and morbidity rates have been reduced, and long-term survival rate has been increased during the past decades, functional outcomes after esophagectomy have not been improved significantly. Of functional derangement after esophagectomy, reflux symptoms are commonly reported findings with prevalence from 20% to 80%. It is one of the most problematic symptoms in patients after esophagectomy (1,2). Disruption of anatomical barriers preventing gastroesophageal reflux, delayed gastrointestinal motility from bilateral vagotomy, positive abdominal pressure, and negative intrathoracic pressure can induce post-esophagectomy reflux. Reflux can lead to anastomotic stenosis and reflux esophagitis in remnant esophagus; furthermore, it can result in life-threatening aspiration pneumonia (3). Therefore, the patients who underwent esophagectomy should adjust dietary habit and change daily lifestyle. Consequently, persistence of reflux symptoms may significantly reduce quality of life after esophagectomy (4,5).

The set of symptoms characteristic of the reflux comprise of typical regurgitation and extra-esophageal manifestations, including cough, dysphagia, and globus pharyngeus (6). The intensity and presentation pattern of reflux vary from patient to patient. In general, proton pump inhibitors are recommended to prevent reflux esophagitis and anastomotic stricture, and to relieve reflux related symptoms (6,7). Furthermore, an anti-reflux anastomosis technique has been proposed to prevent reflux symptoms (8). To enhance gastrointestinal motility, prokinetic agents such as erythromycin and pyloric drainage procedures have been reported to be effective in other studies (9,10). However, results from those studies vary according to literature (11,12).

Therefore, we attempted to quantify the prevalence of reflux symptoms in patients who underwent esophagectomy for esophageal cancer using the reflux symptom index (RSI) questionnaire, originally developed to evaluate significant reflux symptoms and related laryngopharyngeal symptoms. In addition, we aimed to identify predisposing factors for the significant reflux based on the RSI.

Methods

Study population

From April 2017 to July 2017, we prospectively performed a survey study for patients who underwent radical esophagectomy with lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer and agreed to answer the questionnaires at outpatient clinic follow-up. This study was approved and informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of our institute.

In our institution, we routinely performed pyloric drainage procedures (pyloromyotomy or pyloroplasty) and feeding jejunostomy. The jejunal feeding tube was removed when oral diet intake was determined to be sufficient at the first visit to out-patient clinic. Proton pump inhibitor was administered in all patients for at least 2 years and prokinetic agent for 1 year after esophagectomy. The gastric tube with posterior mediastinal route is the preferred approach for reconstruction. Fundoplication or wrapping technique around the anastomosis was not performed.

All surgical procedures and follow-up management were performed by a single surgeon (CHK). Follow-up was performed at a 3-month interval in the first 2 years and a 6-month interval after 2 years. Routine follow-up chest computed tomography scan was performed at 6-month intervals in the first 2 years and in 1-year intervals for the next 3 years. Endoscopic surveillance was performed at 1-year intervals for 2 years. We excluded patients based on the following criteria: (I) first follow-up visit after esophagectomy, (II) benign etiology for esophagectomy, and (III) nil per os for treatment.

Reflux symptom assessment

We used the RSI instrument to quantify the severity of symptoms after esophagectomy. The RSI was developed by Belafsky et al. in 2002 (13). This is a self-administered questionnaire which can be completed within a minute. Patients score each of nine items follows the question, “within the last month, how did the following problems affect you?”: (I) Hoarseness or a problem with your voice, (II) clearing your throat, (III) excess throat mucous or postnasal drip, (IV) difficulty swallowing food, liquids or pills, (V) coughing after you ate or after lying down, (VI) breathing difficulties or choking episodes, (VII) troublesome or annoying cough, (VIII) Sensations or something sticking in your throat, and (IX) heart burn, chest pain, indigestion, or stomach acid coming up. The scale for each item ranges from zero (no problem) to five (severe problem), with a maximum score of 45 (13). A total score ≥13 was defined as a significant cut-off value based on the Korean version of the RSI (14).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). In univariable analysis, categorical variables were compared using a χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test. In univariable and multivariable analysis, potential risk factors for RSI score ≥13 were analyzed using a binary logistic regression test. Variables with P<0.1 in univariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant in both univariable and multivariable analyses.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Table 1 describes the patients characteristics, surgical procedures, operative complication, and follow-up data according to the RSI score. A total of 151 patients were included. The mean age was 64.1±8.8 years. The majority were male patients (n=136, 90.1%) and squamous cell carcinoma (n=143, 94.7%) was the dominant histology. Neoadjuvant treatment was employed in 43 patients (28.5%). Preoperative body weight and body mass index (BMI) did not differ in baseline characteristic variables according to the RSI score.

Table 1. Patients characteristics and the comparison between RSI <13 and RSI ≥13.

| Variable | Total (n=151) | RSI <13 (n=110) | RSI ≥13 (n=41) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 64.1±8.8 | 63.6±8.7 | 65.1±8.9 | 0.351 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 136 (90.1) | 99 (90.0) | 37 (90.2) | 1.000 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment (yes), n (%) | 43 (28.5) | 31 (28.2) | 12 (29.3) | 0.895 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 143 (94.7) | 105 (95.5) | 38 (92.7) | 0.684 |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | ||||

| T category | 0.512 | |||

| cT1 | 69 (45.7) | 50 (45.5) | 19 (46.3) | |

| cT2 | 53 (35.1) | 41 (37.3) | 12 (29.3) | |

| cT3 | 29 (19.2) | 19 (17.3) | 10 (24.4) | |

| N category | 0.580 | |||

| cN0 | 101 (66.9) | 75 (68.2) | 26 (63.4) | |

| cN+ | 50 (33.1) | 35 (31.8) | 15 (36.6) | |

| Preoperative body weight (kg), mean ± SD | 63.3±10.6 | 63.7±10.6 | 62.4±10.5 | 0.509 |

| Preoperative BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 22.9±3.2 | 23.1±3.1 | 22.5±3.5 | 0.326 |

| Operative variables | ||||

| Anastomosis, n (%) | 0.072 | |||

| Cervical | 89 (58.9) | 60 (54.5) | 29 (70.7) | |

| Thoracic | 62 (41.1) | 50 (45.5) | 12 (29.3) | |

| Esophagectomy, n (%) | 0.834 | |||

| Minimally invasive approach | 90 (59.6) | 65 (59.1) | 25 (61.0) | |

| Thoracotomy approach | 61 (40.4) | 45 (40.9) | 16 (39.0) | |

| Conduit, n (%) | 0.087 | |||

| Stomach | 144 (95.4) | 107 (97.3) | 37 (90.2) | |

| Colon | 7 (4.6) | 3 (2.7) | 4 (9.8) | |

| Lymph node dissection, n (%) | ||||

| Recurrent laryngeal lymph node dissection | 124 (82.1) | 94 (85.5) | 36 (87.8) | 0.710 |

| Three-field lymph node dissection | 34 (22.5) | 18 (16.4) | 16 (39.0) | 0.003 |

| Route of conduit reconstruction, n (%) | 0.034 | |||

| Posterior mediastinum | 143 (94.7) | 107 (97.3) | 36 (87.8) | |

| Retrosternal | 8 (5.3) | 3 (2.7) | 5 (12.2) | |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | ||||

| Vocal cord palsy | 38 (25.1) | 19 (17.3) | 17 (41.5) | 0.002 |

| Anastomotic leak | 11 (7.3) | 10 (9.1) | 1 (2.4) | 0.290 |

| Complete resection | 147 (97.3) | 107 (97.3) | 40 (97.6) | 1.000 |

| Follow-up data | ||||

| Time after esophagectomy (month) | 29.7±23.0 | 33.1±22.5 | 20.5±22.1 | <0.001 |

| Time after esophagectomy <2 years, n (%) | 81 (53.6) | 51 (46.4) | 30 (73.2) | 0.003 |

| Time after esophagectomy ≥2 years, n (%) | 70 (46.4) | 59 (53.6) | 11 (26.8) | |

| Postoperative body weight (kg), mean ± SD | 55.8±9.5 | 56.8±9.4 | 53.1±9.0 | 0.032 |

| Postoperative BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 20.3±2.9 | 20.7±2.8 | 19.3±3.0 | 0.010 |

| % change in body weight*, mean ± SD | −11.6±8.4 | −10.5±7.9 | −14.6±9.2 | 0.007 |

| % change in BMI, mean ± SD | −11.0±8.8 | −10.0±8.3 | −13.7±9.5 | 0.021 |

| Endoscopic finding, n (%) | ||||

| Reflux esophagitis | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.563 |

| Anastomosis stenosis | 14 (9.3) | 10 (9.1) | 4 (9.8) | 1.000 |

| History of dilatation | 8 (5.3) | 5 (4.5) | 3 (7.3) | 0.684 |

| Radiologic finding, n (%) | ||||

| Pneumonic infiltration | 8 (5.3) | 2 (1.8) | 6 (14.6) | 0.005 |

| Disease status, n (%) | 1.000 | |||

| No evidence of disease | 141 (93.4) | 103 (93.6) | 38 (92.7) | |

| Recurrence on treatment | 10 (6.6) | 7 (6.4) | 3 (7.3) |

*, % change of body weight = (postoperative body weight-preoperative body weight)/preoperative body weight ×100. Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviation. BMI, body mass index; RSI, reflux symptom index.

Cervical anastomosis was performed in 89 patients (58.9%). Minimally invasive approach was applied in 90 (59.6%). Recurrent laryngeal lymph node dissection and three-field lymph node dissection were performed in 124 patients (82.1%) and 34 patients (22.5%), respectively. Postoperative vocal cord palsy rate and anastomotic leakage rate were 26.4% and 7.3%, respectively. In operative variables, three-field lymph node dissection (P=0.003), retrosternal route of reconstruction (P=0.034), postoperative vocal cord palsy (P=0.002) were more frequently identified in patients with an RSI ≥13.

At the time of completing the questionnaire, the median time after esophagectomy was 23 months (interquartile range: 13–43 months). The mean postoperative body weight and BMI were lower than preoperative values. Patients with RSI ≥13 showed lower postoperative body weight and BMI than those of patients with RSI <13. Percent changes of body weight and BMI were significantly different according to RSI score, meaning that weight loss of patients with RSI ≥13 was more severe than that of patients with RSI <13. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed reflux esophagitis in three patients. However, these patients did not report any symptoms regarding reflux and reflux-associated symptom. Balloon dilatation for anastomotic stenosis was performed in 8 patients (5.3%). Radiologic evaluation revealed aspiration pneumonia in 8 patients. Ten patients had recurrence at local or distant metastasis.

RSI score and risk factors of significant reflux

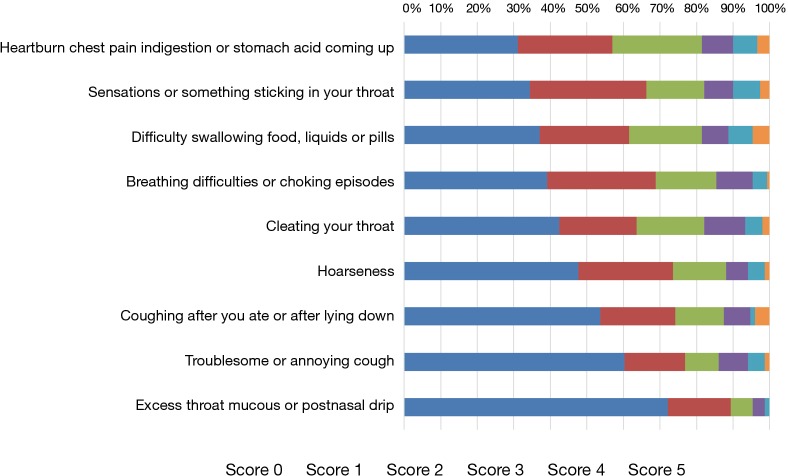

Forty-one (27.2%) patients presented significant reflux, with mean RSI score of 19.9±6.3. The mean score of RSI <13 was 5.8±3.6. Ten patients (6.6%) did not report any symptom. Figure 1 described the relationship between time after esophagectomy and frequency of RSI ≥13. As the time to follow-up increased, the frequency of RSI ≥13 decreased. Figure 2 showed the distribution of reflux symptoms in RSI questionnaire. The question regarding heartburn, chest pain, indigestion, or acid coming up was most frequently responded (n=104, 68.9%); meanwhile, excess throat mucus was the least frequently responded (n=42, 27.8%).

Figure 1.

Time after esophagectomy and frequency of RSI ≥13. RSI, reflux symptom index.

Figure 2.

Distribution of reflux symptoms in RSI questionnaire. RSI, reflux symptom index.

Table 2 presents potential risk factors for RSI ≥13 using binary logistic regression analysis. In univariable analysis, time after esophagectomy <2 years, retrosternal route of reconstruction, three-field lymph node dissection, vocal cord palsy, postoperative body weight and BMI at the time of answering the RSI, percent changes in body weight and BMI, were significantly associated with RSI ≥13. Patients who underwent cervical anastomosis with time after esophagectomy <2 years had a higher risk than those of who underwent thoracic anastomosis with time after esophagectomy ≥2 years (P=0.005). In multivariable analysis, time after esophagectomy <2 years (P=0.001), percent change in body weight (P=0.003), retrosternal route (P=0.005), and vocal cord palsy (P=0.005) were associated with RSI ≥13 after adjusting other potential confounding factors (Table 2). In the subset of posterior mediastinal route with gastric conduit (n=143), time after esophagectomy <2 years [odd ratio (OR) 4.031, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.606–10.119, P=0.003], percent change of body weight (OR 0.915, 95% CI: 0.863–0.970, P=0.003), and vocal cord palsy (OR 3.318, 95% CI: 1.348–8.170, P=0.009) remained risk factors for RSI ≥13.

Table 2. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis for risk factors of in patient with RSI ≥13.

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Time after esophagectomy <2 years | 3.155 | 1.438–6.924 | 0.004 | 4.516 | 1.824–11.185 | 0.001 | |

| Cervical anastomosis | 2.014 | 0.932–4.351 | 0.075 | – | – | – | |

| Thoracic anastomosis (time ≥2 years) | 1.000 | – | 0.005 | – | – | – | |

| Cervical anastomosis (time ≥2 years) | 1.704 | 0.409–7.093 | 0.464 | – | – | – | |

| Thoracic anastomosis (time <2 years) | 2.556 | 0.618–10.573 | 0.195 | – | – | – | |

| Cervical anastomosis (time <2 years) | 6.708 | 1.760–25.571 | 0.005 | – | – | – | |

| Retrosternal route | 4.954 | 1.127–21.769 | 0.034 | 11.626 | 2.090–64.668 | 0.005 | |

| Colonic conduit | 3.856 | 0.824–18.038 | 0.086 | – | – | – | |

| Three field lymph node dissection | 3.271 | 1.462–7.321 | 0.004 | – | – | – | |

| Vocal cord palsy | 3.393 | 1.534–7.505 | 0.003 | 3.531 | 1.454–8.574 | 0.005 | |

| Postoperative body weight (kg) | 0.958 | 0.920–0.997 | 0.035 | – | – | – | |

| Postoperative BMI (kg/m2) | 0.841 | 0.735–0.963 | 0.012 | – | – | – | |

| % change in body weight | 0.940 | 0.898–0.985 | 0.009 | 0.922 | 0.874–0.973 | 0.003 | |

| % change in BMI | 0.951 | 0.910–0.993 | 0.023 | – | – | – | |

RSI, reflux symptom index.

Tables 3,4 outlines differences of RSI score in each item according to the risk factors. Time after esophagectomy <2 years is associated with significantly higher scores than those of time after esophagectomy ≥2 years in most items (Table 3). Meanwhile, a question with regard to heartburn, chest pain, indigestion, or stomach acid coming up was the only item which did not show significant difference with the time after esophagectomy. Patient who had vocal cord palsy reported significantly higher scores in items regarding coughing, choking, dysphagia, and hoarseness than those without vocal cord palsy (Table 4). Approach via a retrosternal route tends to have higher scores in all nine items than those of posterior mediastinal route without statistical significance.

Table 3. Change of RSI score according to the time after esophagectomy.

| RSI | Time after esophagectomy | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <2 years (n=81) | ≥2 years (n=70) | ||

| Total score | 11.75±8.49 | 7.16±5.97 | <0.001 |

| Hoarseness | 1.19±1.30 | 0.74±1.10 | 0.026 |

| Clearing your throat | 1.42±1.35 | 0.96±1.27 | 0.032 |

| Excess throat mucous or postnasal drip | 0.62±0.94 | 0.24±0.69 | 0.006 |

| Difficulty swallowing food, liquids or pills | 1.67±1.64 | 1.00±1.08 | 0.003 |

| Coughing after you ate or after lying down | 1.16±1.45 | 0.69±1.08 | 0.023 |

| Breathing difficulties or choking episodes | 1.33±1.27 | 0.87±1.05 | 0.015 |

| Troublesome or annoying cough | 1.11±1.45 | 0.53±0.96 | 0.004 |

| Sensations or something sticking in your throat | 1.64±1.47 | 0.90±1.08 | <0.001 |

| Heart burn, chest pain, indigestion, or stomach acid coming up | 1.62±1.39 | 1.23±1.30 | 0.080 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. RSI, reflux symptom index.

Table 4. Change of RSI score according to postoperative vocal cord palsy.

| RSI | Vocal cord palsy | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=36) | No (n=115) | ||

| Total score | 13.61±9.38 | 8.37±6.75 | 0.003 |

| Hoarseness | 1.56±1.48 | 0.80±1.08 | 0.007 |

| Clearing your throat | 1.61±1.54 | 1.08±1.24 | 0.063 |

| Excess throat mucous or postnasal drip | 0.53±0.85 | 0.42±0.86 | 0.500 |

| Difficulty swallowing food, liquids or pills | 2.06±1.53 | 1.14±1.35 | 0.001 |

| Coughing after you ate or after lying down | 1.53±1.78 | 0.76±1.07 | 0.018 |

| Breathing difficulties or choking episodes | 1.47±1.34 | 1.01±1.12 | 0.041 |

| Troublesome or annoying cough | 1.44±1.63 | 0.65±1.09 | 0.009 |

| Sensations or something sticking in your throat | 1.72±1.60 | 1.17±1.24 | 0.061 |

| Heart burn, chest pain, indigestion, or stomach acid coming up | 1.69±0.35 | 1.36±1.36 | 0.194 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. RSI, reflux symptom index.

Discussion

Reflux symptoms are frequently reported after esophagectomy. We have determined that prevalence of reflux symptoms using the RSI instrument. Our study revealed that the route of conduit reconstruction, vocal cord palsy, decrease in body weight, and time after esophagectomy were associated with significant reflux after esophagectomy.

The RSI questionnaire is useful to assess typical gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and atypical respiratory symptoms related to reflux (13). In this study, the prevalence of significant reflux was 27%. Typical symptoms of reflux from regurgitation such as heartburn, chest pain, ingestion, or stomach acid coming up were the most frequently reported symptoms. More than 60% of patients reported other extra-esophageal symptoms of reflux such as foreign body sensation, dysphagia, and breathing difficulty. Meanwhile, less than 40% of the patients responded to questions regarding respiratory symptoms including recurrent cough and excess throat mucus. While typical symptoms showed relatively good response to proton pump inhibitors, response to proton pump inhibitors was not liked to resolution of respiratory symptoms in particular (15). Reflux symptoms are various and have a multifactorial etiology. Reflux symptoms are not likely to predict the endoscopic findings of reflux esophagitis (2). In addition, the severity of patients’ symptoms is not correlated with the existence of pathological change of esophagus and the severity of gastroesophageal reflux and duodenogastroesophageal reflux.

We showed several risk factors for significant reflux, including time after esophagectomy, postoperative weight loss, vocal cord palsy, and retrosternal route of reconstruction. Current strategies preventing reflux after esophagectomy focused on reducing acid exposure by decreasing acid production and refluxate from the stomach. In fact, prophylactic proton pump inhibitor reduced the prevalence of anastomotic strictures and reflux related symptoms after esophagectomy (6,7). A prokinetic agent is used to enhance gastrointestinal motility and to decrease duodenogastroesophageal reflux as well (10). Various surgical procedures have been proposed to decrease post-esophagectomy reflux (8,16). However, the Swedish national study demonstrated the combination of potential anti-reflux surgical maneuver including cervical anastomosis, pyloric drainage procedure, and creation of an anti-reflux anastomosis failed to prevent postoperative reflux, and that cervical anastomosis increased postoperative dysphagia significantly (11). Palmes et al. reported that pyloric drainage increased bile reflux after esophagectomy rather than prevented delayed gastric emptying (17). Thus far, no surgical procedure has been universally accepted to decrease reflux symptoms without a risk of dysphagia.

Reflux can be a long-term problem in esophageal cancer, as noted in 10-year survivors (5). The mucosal change in the remnant esophagus induced by acid/bile is a time dependent event (18). However, Nakahara et al. revealed that time after esophagectomy was the only prognostic factor for reflux and that reflux frequency significantly decreased after 2 years after esophagectomy, which were comparable with our study (19). The scores from eight items significantly decreased after 2 years except for the item of heartburn, chest pain, ingestion, or stomach acid coming up. Restoration of gastric motility and acidity may affect those findings. In addition, continued patient education for dietary habit and lifestyle modification may make reflux symptoms more manageable and less problematic for patients.

Regarding changes by acid or bile reflux, thoracic anastomosis is prone to development of columnar mucosa and reflux esophagitis in remnant esophagus (18). However, Johansson et al. reported that additional cervical exploration may lead to a less favorable clearance, resulting from dissection and subsequent scar tissue formation around remnant cervical esophagus (20). Similarly, some studies showed that three-field lymph node dissection and anterior approach for cervical spine surgery had higher risks of postoperative reflux symptoms and dysphagia (21-24). Cervical anastomosis can result in pharyngeal reflux and dysphagia in the early-period after esophagectomy compared to thoracic anastomosis (20). Kato et al. noted that poorer movement of hyoid bone and reduced crycopharyngeal opening in patients with retrosternal route was proved by videofluoroscopy (25). The present study also showed that cervical anastomosis with time after esophagectomy <2 years showed significantly higher risk for RSI ≥13 than thoracic anastomosis with time after esophagectomy ≥2 years in univariable analysis.

Weight loss after esophagectomy can result in poor survival and functional deterioration (26,27). Malnutrition can lead to weakness of the tongue muscles, which may contribute postoperative swallowing difficulty (28). Since weight loss and reflux symptoms can affect each other, the causal relationship between them is uncertain. However, preoperative high BMI was a risk factor for weight loss after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer (29). Furthermore, a significant number of patients who underwent esophagectomy for esophageal cancer failed to return to their preoperative body weight after three years (30). In addition, retrosternal route may impact on the nutritional status after esophagectomy. Retrosternal and posterior mediastinal routes showed similar outcomes in postoperative complication (31). However, a multi-center study revealed that the route of conduit reconstruction has impact on the nutritional status; the retrosternal route is associated with higher risk of malnutrition (32). In particular, we prefer retrosternal route of reconstruction for the colonic conduit, when the gastric conduit is unavailable. Therefore, the impact of retrosternal route of reconstruction seemed to be overestimated. In the sub-group analysis of gastric conduit with posterior mediastinal route, time after esophagectomy, postoperative weight loss, and vocal cord palsy were still associated with significant reflux.

Several items of RSI questionnaire are closely related to the symptoms from vocal cord palsy. Consequently, postoperative vocal cord palsy would be likely to have a high score of RSI. A large number of patients underwent recurrent laryngeal lymph dissection and three-field lymph nodes dissection. Regardless of hoarseness, laryngoscopic examination of the vocal cord in conjunction with early intervention by an otolaryngologist was routinely performed in all patients on postoperative day 3 in our institution. In addition, a number of vocal cord palsy after esophagectomy tend to be temporary in nature and palsy resolved after 6 months (33). Hence, most patients who experienced vocal cord palsy were treated or recovered at the time of evaluation. However, the history of vocal cord palsy remained a significant risk factor for RSI ≥13.

There are several limitations in this study. This study lacked objective measurements and its conclusions were based on subjective patient-reported symptoms only. Additional quality measurement, pH monitoring, histopathologic confirmation combined with the RSI could strengthen the results. Since all patients received proton pump inhibitors and prokinetic agents, the effect of medication was not determined in this study. Moreover, longitudinal evaluation should be performed to consolidate our results.

Despite of several limitations, we conclude that reflux-related symptoms including extra-esophageal manifestations are common. Furthermore, we suggest that short duration after esophagectomy, vocal cord palsy, retrosternal route of reconstruction, and postoperative weight loss are significant predisposing factors for significant reflux after esophagectomy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was approved by Seoul National University Hospital Clinical Research Institute with informed consent not required (IRB No. 1804-018-934).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: CHK serves as the unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Thoracic Disease from Sep 2018 to Aug 2020. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Aly A, Jamieson GG. Reflux after oesophagectomy. Br J Surg 2004;91:137-41. 10.1002/bjs.4508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shibuya S, Fukudo S, Shineha R, et al. High incidence of reflux esophagitis observed by routine endoscopic examination after gastric pull-up esophagectomy. World J Surg 2003;27:580-3. 10.1007/s00268-003-6780-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishimura K, Tanaka T, Tsubuku T, et al. Reflux esophagitis after esophagectomy: impact of duodenogastroesophageal reflux. Dis Esophagus 2012;25:381-5. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01268.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarpa M, Valente S, Alfieri R, et al. Systematic review of health-related quality of life after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:4660-74. 10.3748/wjg.v17.i42.4660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schandl A, Lagergren J, Johar A, et al. Health-related quality of life 10 years after oesophageal cancer surgery. Eur J Cancer 2016;69:43-50. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okuyama M, Motoyama S, Maruyama K, et al. Proton Pump Inhibitors Relieve and Prevent Symptoms Related to Gastric Acidity after Esophagectomy. World J Surg 2008;32:246-54. 10.1007/s00268-007-9325-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansson J, Oberg S, Wenner J, et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors on benign anastomotic stricture formations after esophagectomy and gastric tube reconstruction: results from a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 2009;250:667-73. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bcb139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aly A, Jamieson GG, Watson DI, et al. An antireflux anastomosis following esophagectomy: a randomized controlled trial. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:470-5. 10.1007/s11605-009-1107-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonoff MB, Puri V, Meyers BF, et al. Comparison of pyloric intervention strategies at the time of esophagectomy: is more better? Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:1950-7; discussion 1957-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Richter JE. Duodenogastric reflux-induced (alkaline) esophagitis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2004;7:53-8. 10.1007/s11938-004-0025-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Schaaf M, Johar A, Lagergren P, et al. Surgical Prevention of Reflux after Esophagectomy for Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:3655-61. 10.1245/s10434-013-3041-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritz S, Feilhauer K, Schaudt A, et al. Pylorus drainage procedures in thoracoabdominal esophagectomy - a single-center experience and review of the literature. BMC Surg 2018;18:13. 10.1186/s12893-018-0347-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). J Voice 2002;16:274-7. 10.1016/S0892-1997(02)00097-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung YH, Chang DY, Jang JH, et al. Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) and Reflux Finding Score (RFS) of Persons Taking Health Checkup and Their Relationship with Gastrofiberscopic Findings. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg 2007;50:431-7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yadlapati R, Pandolfino JE, Lidder AK, et al. Oropharyngeal pH Testing Does Not Predict Response to Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy in Patients with Laryngeal Symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1517-24. 10.1038/ajg.2016.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Urschel JD, Blewett CJ, Young JEM, et al. Pyloric Drainage (Pyloroplasty) or No Drainage in Gastric Reconstruction after Esophagectomy: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Dig Surg 2002;19:160-4. 10.1159/000064206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmes D, Weilinghoff M, Colombo-Benkmann M, et al. Effect of pyloric drainage procedures on gastric passage and bile reflux after esophagectomy with gastric conduit reconstruction. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2007;392:135-41. 10.1007/s00423-006-0119-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rice TW, Goldblum JR, Rybicki LA, et al. Fate of the esophagogastric anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;141:875-80. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakahara Y, Yamasaki M, Miyazaki Y, et al. Reflux after esophagectomy with gastric conduit reconstruction in the posterior mediastinum for esophageal cancer: original questionnaire and EORTC QLQ-C30 survey. Dis Esophagus 2018;31:1-7 10.1093/dote/doy001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson J, Johnsson F, Groshen S, et al. Pharyngeal reflux after gastric pull-up esophagectomy with neck and chest anastomoses. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;118:1078-83. 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70104-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rihn JA, Kane J, Joshi A, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux after anterior cervical surgery: a controlled, prospective analysis. Spine 2011;36:2039-44. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31821795f1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura M, Kido Y, Hosoya Y, et al. Postoperative gastrointestinal dysfunction after 2-field versus 3-field lymph node dissection in patients with esophageal cancer. Surg Today 2007;37:379-82. 10.1007/s00595-006-3413-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joaquim AF, Murar J, Savage JW, et al. Dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a systematic review of potential preventative measures. Spine J 2014;14:2246-60. 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee MJ, Bazaz R, Furey CG, et al. Risk factors for dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a two-year prospective cohort study. Spine J 2007;7:141-7. 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato H, Miyazaki T, Sakai M, et al. Videofluoroscopic evaluation in oropharyngeal swallowing after radical esophagectomy with lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer. Anticancer Res 2007;27:4249-54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hynes O, Anandavadivelan P, Gossage J, et al. The impact of pre- and post-operative weight loss and body mass index on prognosis in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2017;43:1559-65. 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker M, Halliday V, Williams RN, et al. A systematic review of the nutritional consequences of esophagectomy. Clin Nutr 2016;35:987-94. 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen KN. Managing complications I: leaks, strictures, emptying, reflux, chylothorax. J Thorac Dis 2014;6 Suppl 3:S355-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitagawa H, Namikawa T, Munekage M, et al. Analysis of Factors Associated with Weight Loss After Esophagectomy for Esophageal Cancer. Anticancer Res 2016;36:5409-12. 10.21873/anticanres.11117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin L, Lagergren P. Long-term weight change after oesophageal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 2009;96:1308-14. 10.1002/bjs.6723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urschel JD, Urschel DM, Miller JD, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of route of reconstruction after esophagectomy for cancer. Am J Surg 2001;182:470-5. 10.1016/S0002-9610(01)00763-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamasaki M, Miyata H, Yasuda T, et al. Impact of the route of reconstruction on post-operative morbidity and malnutrition after esophagectomy: a multicenter cohort study. World J Surg 2015;39:433-40. 10.1007/s00268-014-2819-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scholtemeijer MG, Seesing MFJ, Brenkman HJF, et al. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: incidence, management, and impact on short- and long-term outcomes. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:S868-78. 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]