Abstract

Oxidative stress and inflammation are commonly present in many chronic diseases. These responses are closely related to pathophysiological processes. The inflammatory process can induce oxidative stress and vice versa through the activation of multiple pathways. Therefore, agents with antioxidant and/or anti-inflammatory activities are very useful in the treatment of many pathologies. Clerodendrum cyrthophyllum Turcz, a plant belonging to the Verbenaceae family, is used in Vietnamese traditional medicine for treating migraine, hypertension, inflammation of the throat, and rheumatic arthritis. Despite its usefulness, studies on its biological properties are still scarce. In this study, ethanol extract (EE) of leaves of C. cyrtophyllum showed protective activity against CuSO4 toxicity. The protective activity was proven to relate to antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. EE exhibited relatively high antioxidant activity (IC50 of 16.45 µg/mL) as measured by DPPH assay. In an in vivo anti-antioxidant test, three days post fertilization (dpf) zebrafish larvae were treated with different concentrations of EE for 1 h and then exposed to 10 µM CuSO4 for 20 min to induce oxidative stress. Fluorescent probes were used to detect and quantify oxidative stress by measuring the fluorescent intensity (FI) in larvae. FI significantly decreased in the presence of EE at 5 and 20 µg/mL, demonstrating EE’s profound antioxidant effects, reducing or preventing oxidative stress from CuSO4. Moreover, the co-administration of EE also protected zebrafish larvae against oxidative damage from CuSO4 through down-regulation of hsp70 and gadd45bb expression and upregulation of sod. Due to copper accumulation in zebrafish tissues, the damage and oxidative stress were exacerbated overtime, resulting in the upregulation of genes related to inflammatory processes such as cox-2, pla2, c3a, mpo, and pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (il-1ß, il-8, tnf-α, and il-10, respectively). However, the association of CuSO4 with EE significantly decreased the expression of cox-2, pla2, c3a, mpo, il-8, and il-1ß. Taken together, the results suggest that EE has potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities and may be useful in the treatment of various inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Anti-inflammation, oxidative stress, antioxidant, CuSO4, zebrafish larvae, Clerodendrum cyrtophyllum

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress and inflammation contribute to the pathogenesis of many chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and aging [1]. They are tightly linked with one another. If inflammation is the primary event, the activated macrophages and neutrophils liberate large amounts of reactive species at the site of inflammation [2]. Consequently, oxidative stress will develop and further increase inflammation. Conversely, if oxidative stress appears, the overproduced reactive oxygen/nitrogen species can induce inflammation through upregulation of pro-inflammatory gene expression [1,3]. Inflammation will eventually further accentuate oxidative stress. In clinical practice, identification and treatment of the primary abnormality are very important. However, the relationship between inflammation and oxidative stress is interdependent; treating only the primary abnormality may not always be successful [1]. Therefore, finding agents that inhibit both ROS production and inflammatory mediators has been considered a promising strategy for preventing or treating diseases associated with chronic inflammatory conditions.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) have been widely used in developmental biology and drug discovery. Several characteristics make zebrafish a convincing tool in drug discovery, such as low maintenance costs, rapid embryogenesis, transparency, high similarity between the human and zebrafish genomes, etc. [4]. More specifically related to this research, oxidative and inflammatory responses can be robustly and easily induced and visualized in zebrafish, particularly in the early stages [5]. Copper is an essential micronutrient but misregulation of intracellular levels can become toxic to many cell types. Under inflammatory conditions, serum copper levels increase and trigger oxidative stress responses that activate inflammatory responses [5]. The zebrafish copper-induced inflammation model has been used previously and presents several advantages as it is a non-invasive and sterile method, in comparison to methods involving physical damage and the use of infectious agents, besides its gentle manipulation of the larvae [6]. In this study, we used CuSO4 as an agent to induce an inflammatory response through the oxidative stress reaction to study the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of ethanol extracts of Clerodendrum cyrthophyllum Turcz.

C. cyrthophyllum, a plant belonging to the Verbenaceae family, is widely distributed in tropical countries such as Vietnam, China, India, Japan, Korea, and Thailand [7]. In Vietnam, it is used for treating migraine, hypertension, inflammation of the throat, and rheumatic arthritis. In several studies, phenolic acids and flavonoids have been isolated from various plant parts [8]. Total phenols and flavonoids displayed good antioxidant activity and potential anti-inflammatory activity in several experimental models [9]. Investigations on this plant suggest that it has potential as an alternative treatment for inflammatory diseases. However, further investigation is needed to identify the exact mechanism of action and pathways that are modulated by this plant. In this study, we investigated the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of the ethanol extract of C. cyrthophyllum using the zebrafish copper-induced inflammation model to elucidate the molecular mechanisms to explain its effects, and provide scientific evidence for using it in traditional medicine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), quercetin, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA), copper sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4·5H2O), and pyrocatechol violet (PV) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other reagents were of the highest commercially available grade.

2.2. Preparation of the Ethanol Extract of Clerodendrum cyrtophyllum Turcz (EE)

2.2.1. Plant Collection

Leaves of Clerodendrum cyrtophyllum Turcz Verbenaceae were collected from northern provinces of Vietnam in June 2018, by Nguyen Kim Thanh from Vietnam National University (VNU-BIOL). A voucher specimen (HNU 024106) was deposited at the Botanical Museum of Hanoi, University of Science. Leaves were cleaned and dried for 72 h to a constant weight using a hot air oven at 40 °C before extraction. Dried leaves were then ground in a blender to fine powder (size smaller than 0.5 mm).

2.2.2. Preparation of Total Extract

Given that polar (aqueous) extracts are used in traditional practice, we selected ethanol to extract polar secondary metabolites, minimizing the extraction of mineral salts and polysaccharides. For this, 100 g of dried leaf powder was extracted with 1000 mL 95% ethanol at 60 °C in a water bath with 360 rpm agitation for 4 h. The extract was then filtered and collected. The residue was extracted another two times using the same procedure. The collected ethanol extracts were then combined, concentrated on a rotary evaporator (40 °C) under reduced pressure, and lyophilized to obtain the crude extract. The yield of extract was 11.3% relative to the dried leaf powder. The crude extract was stored at −20 °C until use. After the extraction, the EE was analyzed with various analytical techniques including colorimetric methods, HPTLC (high performance thin layer chromatography), and mass spectrometry analyses. The extract presents a concentration of total phenolic compounds of 23.3 ± 1.5 GAE mg/g and flavonoid of 2.97 ± 0.01 QE mg/g expressed in dry weight of leaves material.

2.3. Fish and Experimental Conditions

The adult wild–type AB zebrafish (Danio rerio) were maintained in a recirculating ZebTec housing system (Techniplast) at 28 °C with a 12:12 h (light:dark) photoperiod. Conductivity was maintained at approximately 500 μS/cm, pH 7.2. Fish were fed ad libitum three times daily. The day before mating, males and females (2:2) were placed in spawning tanks. Naturally spawned embryos were obtained within 30 min after the lights were switched on in the morning. The embryos were selected visually using a binocular microscope and only fertilized and normally developed eggs were selected. Selected eggs were placed in embryo medium at 28 °C. Embryo medium was renewed every 24 h. Hatched larvae at three days post fertilization (dpf) were used for subsequent experiments. Since zebrafish larvae below 120 h old are not considered animals [10], no animal test authorization is required according to European legislation (EU Directive, 2010/63/EU). All experiments were terminated at 120 h post fertilization (hpf). The term “larvae” refers to hatched embryos up to 120 hpf that are using up the yolk-sac reserves and do not yet feed externally (also called yolk-sac larva, early larva, pre-larva, or eleuthero embryos) [10].

2.4. Experimental Design

2.4.1. Preparation of Test Samples

The dry ethanol extract of Clerodendrum cyrtophyllum Turcz (EE) was dissolved in DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) to make a stock solution of 50 mg/mL. The stock solution was diluted to different concentrations using fresh larvae medium (dechlorinated water with conductivity approximately 500 μS/cm, pH 7.2) so that the final concentration in each experimental well was 5, 20, and 40 µg/mL.

2.4.2. Protective Effect of EE against CuSO4 Toxicity in Zebrafish Larvae

Mortality was used as an initial endpoint to characterize and evaluate the protective effect of the EE against CuSO4 toxicity in zebrafish larvae. Zebrafish larvae 3 dpf at a density of twenty larvae per well were incubated with EE at different doses (5, 20, and 40 µg/mL) for 1 h and then stimulated with a lethal dose (20 µM) of CuSO4 for 24 h. All treatments were performed in six-well culture plates. The parameter assessed was mortality rate at 24 h.

2.4.3. Anti-Oxidant Effect of EE

In Vitro Antioxidant Tests: Measurement of DPPH Radical Scavenging Capacity

The ability of the prepared extract to scavenge DPPH radicals was determined by the method described by Cheng-zhong et al. (2013) [11] with slight modifications. Briefly, a 20 µL solution of EE in different concentrations (5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, and 500 µg/mL) was added to 180 µL methanol solution of DPPH (0.1 mM). Quercetin was used as a positive control and methanol was used as a blank. All reaction mixtures were shaken and incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance was then measured at 517 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. All samples were analyzed in triplicate. The DPPH scavenging ability of the plant extracts was calculated using the following equation:

| %Scavenging Activity = (Abs control − Abs sample) × 100/(Abs control) |

where Abs control is the absorbance of the blank and Abs sample is the absorbance of the sample.

The antioxidant activity was reported in terms of IC50 (concentration of extract necessary to decrease the initial concentration of DPPH by 50%).

Cu2+ Chelation Ability

The ability of EE to chelate Cu2+ was assessed using the method described by Santos et al. (2017) that employs pyrocatechol violet (PV) as the chromogen agent [12]. Briefly, in each well, 30 µL solution of EE in different concentrations (5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, and 500 µg/mL) or water (control) were mixed with 200 µL of sodium acetate buffer (50 mmol/L, pH 6.0). Then, 30 µL of a 100 mg/L CuSO4.5H2O solution were added in each well and let react for 2 min. After 2 min, 8.5 µL of solution pyrocatechol violet 2 mmol/L were added to initiate the reaction. All reaction mixtures were shaken and incubated for 10 min at 25 °C. The absorbance was then measured at 632 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Cu2+ chelating ability of EE was calculated as:

| Cu2+ chelating ability of EE (%) = [(Abs control − Abs sample)/Abs control] × 100. |

In Vivo Antioxidant Test

Generation of reactive oxygen species was determined using the membrane-permeable fluorescent dye 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA). H2DCFDA is hydrolyzed inside cells to the non-fluorescent compound 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein, which emits fluorescence when oxidized to 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF). Thus, the fluorescence emitted by DCF directly reflects the overall oxidative status of a cell [13,14]. Zebrafish larvae (3 dpf) were transferred into 12-well plates containing 940 µL embryo media, 6 larvae per well. Groups of 6 hatched larvae were treated with EE at different doses of 5, 20, and 40 µg/mL or 100 mM quercetin for 1 h and then exposed to 10 µM CuSO4 for 20 min to induce oxidative stress. After 20 min of exposure, larvae were washed twice with fresh larvae medium and incubated with H2DCFDA (2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate) solution (20 µg/mL) for 1 h in the dark at 28 ± 1 °C. After incubation, zebrafish larvae were washed 3 times in fresh larvae medium, anesthetized with 0.0003% MS-222 (tricaine methane-sulfonate), and transferred to flat 24-well plates (one larva per well) before observation and photography under a fluorescence microscope. Each larva was placed on the lateral side with the head preferably on the left side with respect to the observer. Fluorescence intensity of an individual larva was quantified using Autovision software and a BD pathway 855 system (BD Biosciences). Larvae exposed to CuSO4 but not treated with EE were used as controls.

The stock solutions of H2DCFDA were prepared in DMSO. The solutions were protected from light and stored at −20 °C until used for the analysis. Working solutions were prepared on the day of the experiment.

Quantitative Real–Time PCR

Three days post fertilization zebrafish larvae were transferred into 12-well plates containing 940 µL embryo media, 20 larvae per well. A group of 20 hatched larvae was first treated with EE at different doses of 5, 20, and 40 µg/mL for 1 h and then exposed to 10 µM CuSO4 (a concentration capable of inducing oxidative stress and inflammation) for 4 h. After 4 h, larvae were collected and stored at –80 °C for qPCR analysis to evaluate the effects of EE on the expression of genes related to oxidative stress, such as sod, gpx4, hsp70, and gadd45bb.

Total RNA Extraction, DNase Treatment and Reverse Transcription

Total RNA was extracted from these larvae using Trizol Reagent solution (Ambion, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, United states) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The pellet containing RNA was dried and resuspended in 100 µL of RNase-free water. The concentration of total RNA was determined spectrophotometrically at A260/A280 and A260/A230 nm using a NanoDropTM 1000 (Thermo Scientific). RNA integrity was checked by denaturating gel electrophoresis (1.2% agarose). The extracted RNA samples were then subjected to DNase treatment (DNA-free™ DNA Removal Kit, Invitrogen) to avoid DNA contamination. One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into double-stranded cDNA using the RevertAid RT kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The resulting cDNA was used to measure the expression of 5 oxidant genes in a real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Two housekeeping genes (β-actin and elongation factor 1α (efl1-α)) were used as references. The expression of genes encoding sod, cat, gpx4, hsp70, and gadd45bb was evaluated. The list of specific primers used is given in Table 1. Primers were designed on Primer3 software. Amplifix software was used to check the quality of the primers. The efficiency of each primer was confirmed by RT-PCR.

Table 1.

Primer pairs used in this study.

| Gene Name | Function | GenBank Accession No. | Forward and Reverse Primer Sequences (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | Housekeeping gene | AF057040 |

Fwd: CCCCATTGAGCACGGTATTG Rev: ATACATGGCAGGGGTGTTGA |

| Elongation factor 1 alpha (efl1-α) | Housekeeping gene | L23807.1 |

Fwd: CCAAGGAAGTCAGCGCATAC Rev: CCTCCTTGCGCTCAATCTTC |

| Interleukin-1 (il-1ß) | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | NM_212844.2 |

Fwd: AAAGTGCGCTTCAGCATGTC Rev: GCTGGTCGTATCCGTTTGGA |

| Interleukin -8 il-8 (cxcl8b.1) | cytokine | NM_001327985.1 |

Fwd: GCCTTCATGCTTCTGATCTGC Rev: AATCACCCACGTCTCGGTAGGA |

| Cyclooxygenase -2 (ptgs2a or cox2) | Catalyze the formation of prostaglandin, thromboxane | NM_153657.1 |

Fwd: ACAGATGCGCTACCAGTCTT Rev: CCCATGAGGCCTTTGAGAGA |

| Phospholipase A2 pla2 (pla2g4aa) | Provide precursors for generation of eicosanoids | NM_131295.2 |

Fwd: TCATGTCTCCTGGGCTGTTT Rev: CCAGCTCCTCCTCCATAGTG |

| Tumor necrosis factor (tnf-α) | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | AB183467 |

Fwd: CACAAAGGCTGCCATTCACT Rev: GATTGATGGTGTGGCTCAGGT |

| nf- ƙb (nkap) | A ubiquitous transcription factor | NM_001003414.1 |

Fwd: GGTCGGACAGAGATCACGGATT Rev: TGCTGTTCTTCACGTCCTCT |

| Interleukin -10 (il-10) | Anti-inflammatory cytokine | AY887900.1 |

Fwd: AGTCATCCTTTCTGCTCTGCT Rev: AAAGCCCTCCACAAATGAGC |

| c3a (c3a.1) | Complement 3a | NM_131242.1 |

Fwd: GTACGAGGCGAACAACTGGA

Rev: CATCATACGCCGCAGCTTTC |

| mpo | Myeloperoxidase | AF349034.1 |

Fwd: GTGGTCGTGTCGGTTCTCTT Rev: GCAGATTATGCGGGCCATTG |

| sod (sod1) | Superoxide dismutases | NM_131294.1 |

Fwd: ATGGTGAACAAGGCCGTTTG Rev: AAAGCATGGACGTGGAAACC |

| gpx4b | glutathione peroxidase | BC095133.1 |

Fwd: TGAGAAGGGTTTACGCATCCTG Rev: TGTTGTTCCCCAGTGTTCCT |

| hsp70 | Protect cell from oxidative stress | AF210640.1 |

Fwd: CAACGTGCTGATCTTTGACC Rev: TCCTCTTGGCTCGTTCACAT |

| gadd45bb | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible | NM_001012386.2 |

Fwd: CGCTTCAGATCCACTTCACG Rev: TCCCACTTCCTTCAGCTTGA |

RT-PCR was performed using an ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Five microliters of 25-fold diluted cDNA template was mixed with 5 μL of each primer (5 μM) and 10 μL of SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) to a final volume of 20 μL. The standard cycling conditions were 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s and 60 °C for 30 s. All reactions were performed as technical triplicates. For analysis, a standard curve of a pool of the cDNA of all samples was constructed following the absolute quantification method (Bio-Rad) [15]. The equation for the linear regression line

| CT = m(log quantity) + b. |

where b is the y-intercept and m is the slope of the linear regression. Based on the equation for the linear regression, we can determine the quantity of an unknown sample:

The ratios of the quantity of candidate gene/average quantity of housekeeping genes were subsequently calculated for each candidate gene and used to assess the differences in expression levels between experimental groups.

2.4.4. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of EE

To evaluate the anti-inflammatory properties of EE, a similar experiment was designed using 10 µM CuSO4 to stimulate inflammation. After 4 and 24 h of CuSO4 exposure, the expression of genes related to inflammatory processes were analyzed in zebrafish larvae using qPCR.

The resulting cDNA was used to measure the expression of 9 immune system genes in a real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Two housekeeping genes (ß-actin and efl1-α) were used as the reference. The expression of genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (il-1ß, il-8, and tnf-α), neutrophil (mpo), complement 3a (c3a), phospholipase A2 (pla2), cox-2, transcription factor NF-κB (nf-ƙb), and an anti-inflammatory response cytokine (il-10) were evaluated. The list of specific primers used is given in Table 1. Primers were designed on Primer3 software. Amplifix software was used to check the quality of the primers. The efficiency of each primer was confirmed by RT-PCR.

2.5. Data Presentation and Statistical Analyses

Data analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, United States). In the case of data with a normal distribution, data are shown as mean ± SEM; a t-test and one-way analysis of variance with LSD post hoc test were used for statistical comparisons to determine treatment differences. A probability level of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

When data were not normally distributed, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks was performed, followed by a Mann–Whitney test to determine significant differences between the experimental groups. When non-parametric statistics were used, the data are presented using Turkey’s boxplot (bottom and top of the box are 25th and 75th percentile, the horizontal line in the box is the median, the ends of the whiskers represent 1.5 times the interquartile distance, and the individual dots are values that fall outside the whiskers).

3. Results

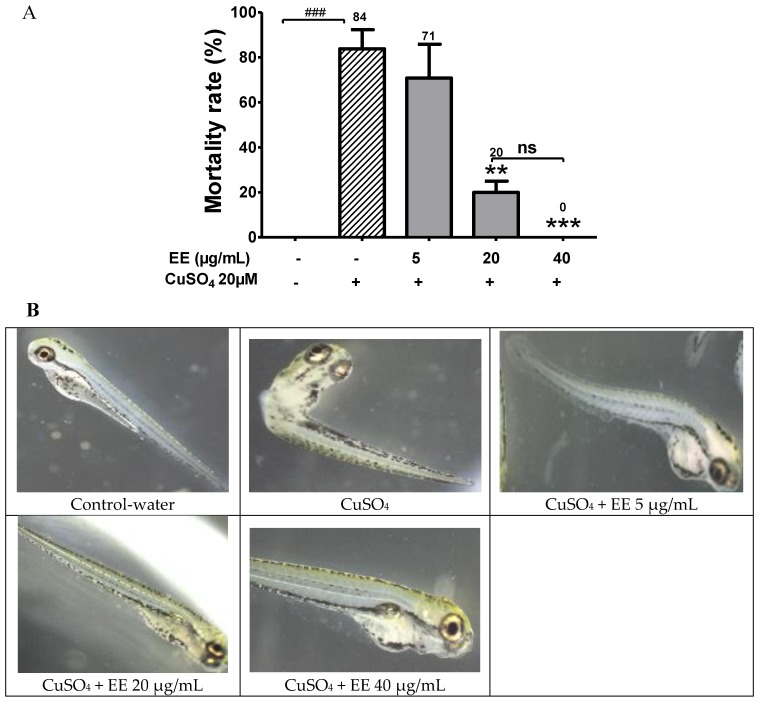

3.1. Protective Activity of EE against CuSO4 Toxicity in Zebrafish Larvae

In the present study, we showed that the exposure of CuSO4 at high dose of 20 µM induced mortality in zebrafish larvae (Figure 1A), and EE at the doses of 20 and 40 µg/mL effectively inhibited the toxicity of CuSO4, improving fish survival. The mortality of larvae which were treated with CuSO4 alone was 84%, while the mortality rate was 20% for co-administration with EE at the 20 µg/mL dose. At the high EE dose 40 µg/mL, no dead larvae were observed after 24 h.

Figure 1.

Protective effect of the ethanol extract of C. cyrtophyllum leaves (EE) against CuSO4 toxicity. (A) Mortality rates of zebrafish larvae after treatment with 20 µM CuSO4 and ethanol extracts of C. cyrtophyllum (EE) at different doses. (B) Representative photographs of zebrafish larvae treated with 20 µM CuSO4 and ethanol extracts of C. cyrtophyllum (EE) at different doses. The data are presented as mean ± S.E. for three different experiments performed in triplicate. ### p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 compared to the CuSO4 alone group.

The protective effect of EE against CuSO4 was further confirmed by representative photographs of zebrafish larvae treated with 20 µM CuSO4 and EE at different doses. Photographs of zebrafish showed that treatment only with CuSO4 induced toxicity in larvae. Several malformations were observed, including trunk curvature, shorter body length, and loss of moving ability. Interestingly, in the groups that were treated with copper plus EE, the extent of morphological abnormality decreased. At high dose, EE 40 µg/mL protected zebrafish larvae against toxicity of CuSO4, and no morphological abnormality was observed (Figure 1B). These results provide evidence that EE protected larvae from CuSO4 toxicity in a dose-dependent manner. To elucidate the protective mechanisms of EE, we further evaluated its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities.

3.2. Antioxidant Effect

3.2.1. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of EE

Effect of the Ethanol Extract of C. cyrtophyllum Leaves (EE) on DPPH Radical Scavenging

The free-radical scavenging ability of EE is shown in Table 2. The positive control, quercetin, has a strong DPPH scavenging property with a maximum achievable response (Emax) of 93.82%. The concentration that gave the half-maximal effect (IC50) was 3.93 ± 1.09 µg/mL. Similar to quercetin, EE showed a strong antioxidant activity with an IC50 value of 16.45 ± 1.11 μg/ mL and an Emax of 94.24%. The results indicate that EE may act as a DPPH radical scavenger.

Table 2.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of EE.

| EE | Quercetin | |

|---|---|---|

| Emax (%) | 94.24 | 93.82 |

| IC50 (µg/mL) | 16.45 ± 1.11 | 3.93 ± 1.09 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | 11.63–23.27 | 2.98–5.17 |

| R2 | 0.9958 | 0.98995 |

| Number of Points Analyzed | 7 | 7 |

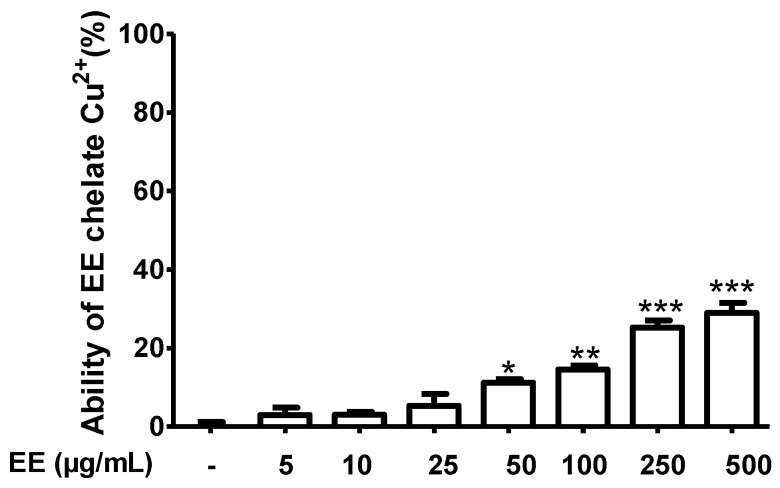

Effect of the Ethanol Extract of C. cyrtophyllum Leaves (EE) on Cu2+ Chelation Ability

The ability of EE to chelate Cu2+ is shown in Figure 2. Compounds in EE bind Cu2+ with the formation of a complex EE–Cu2+. EE showed a weak copper chelating activity. At the highest concentration of 500 µg/mL, Cu2+ chelating ability of EE only reached 29%.

Figure 2.

Effect of the ethanol extract of C. cyrtophyllum leaves (EE) on Cu2+ chelation ability. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. for three different experiments performed in triplicate. * p < 0.05, ** and *** p < 0.001 compared to the control group.

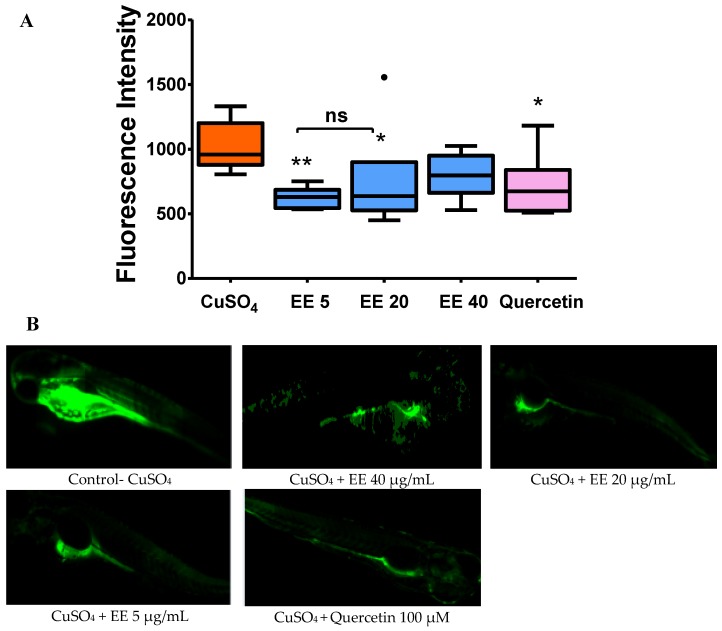

3.2.2. Effect of the Ethanol Extract of C. cyrtophyllum Leaves (EE) on the Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species

As shown in Figure 3, quercetin 100 µM inhibited ROS formation, thus fluorescence intensity significantly decreased compared to the CuSO4 group. Similar to quercetin, co-administration with EE at 5 and 20 µg/mL significantly decreased fluorescence intensity. These results suggest that administration of EE can limit the generation of reactive oxygen species generated in response to CuSO4.

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effect of ethanol extract (EE) from leaves of C. cyrtophyllum Turcz on CuSO4-stimulated ROS production in zebrafish larvae. The zebrafish were exposed to different concentrations of EE (5, 20, and 40 µg/mL) or 100 µM quercetin for 1 h and then exposed to 10 µM CuSO4 for 20 min to induce oxidative stress. After 20 min, larvae were incubated with H2DCFDA (20 µg/mL) for 1 h. Fluorescent probes were used to detect and quantify oxidative stress by measuring the fluorescent intensity (FI) in larvae using Autovision software and a BD pathway 855 system (BD Biosciences). (A) Fluorescence intensity obtained from individual zebrafish larvae. The data are presented as medians for six different larvae, * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 compared to the CuSO4 alone Group. (B) Representative fluorescence micrographs of ROS production.

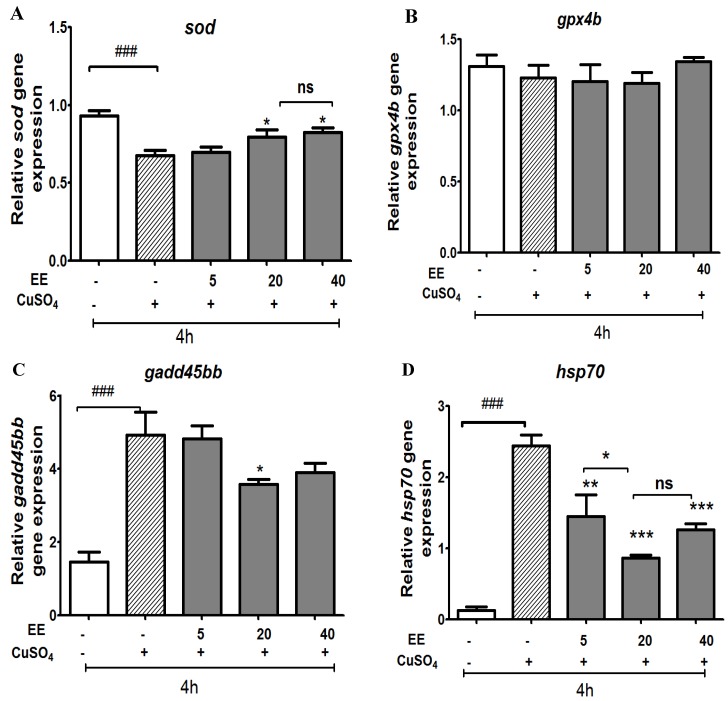

3.2.3. Effect of the Ethanol Extract of C. cyrtophyllum Leaves (EE) on Antioxidant Gene Expression

To further investigate the mechanism of antioxidant action, we measured the effects of EE on the expression of two genes involved in antioxidant systems (sod and gpx4). As shown in Figure 4, exposure to copper sulfate resulted in a significant reduction in sod compared to the control group. EE at 20 and 40 µg/mL significantly increased sod, whereas expression of gp4x was not affected by any treatment.

Figure 4.

Effect of ethanol extract (EE) of C. cyrtophyllum Turcz leaves on expression of antioxidant genes: sod (A); gpx4 (B); hsp70 (C), and gadd45bb (D). The zebrafish larvae were exposed to EE for 1 h and to CuSO4 10 µM for 4 h. After 4 h, larvae were collected for qPCR analysis. The relative gene expressions are presented as the ratio of the quantity of candidate gene/average quantity of housekeeping genes. A pool of 20 larvae per group (n = 3) was used. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. for three different experiments performed in triplicate. * p < 0.05, ** and ### p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 compared to the CuSO4 alone group.

We also designed experiments to examine whether copper sulfate is capable of inducing stress response or growth arrest and DNA damage through evaluating the expression levels of a growth arrest and DNA-damage gene (gadd45bb) and a stress-related gene (hsp70). As shown in Figure 4, CuSO4 induced a stress response; the mRNA expression levels of hsp70 and gadd45bb were significantly upregulated. The co-administration of EE at the doses of 5, 20, and 40 µg/mL protected zebrafish larvae against oxidative damage due to CuSO4 and therefore the expressions of hsp70 and gadd45bb were down-regulated.

3.3. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of EE

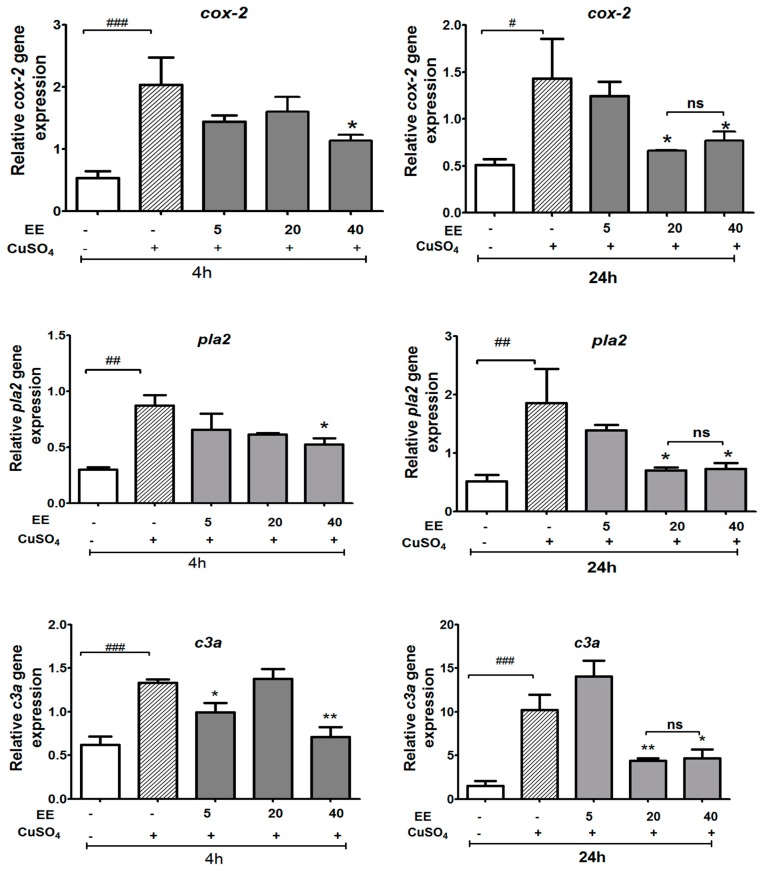

3.3.1. Effect of the Ethanol Extract of C. cyrtophyllum Turcz Leaves on the Expressions of c3a, cox-2, and pla2 Genes

For the expression of two genes involved in the eicosanoid pathway (cox-2 and pla2), and of the complement gene c3a, as shown in Figure 5, CuSO4 markedly increased the expression of cox-2, c3a, and pla2 genes when compared with the control group. EE at 40 µg/mL greatly suppressed the CuSO4-induced mRNA levels of cox-2, pla2, and c3a at both 4 and 24 h after copper sulfate exposure, while EE at 20 µg/mL only showed an effect on expression after 24 h.

Figure 5.

Effect of ethanol extract (EE) of C. cyrtophyllum Turcz leaves on the expression of genes in the eicosanoid pathway (pla2, cox-2, and c3a.). The zebrafish larvae were exposed to EE for 1 h and CuSO4 10 µM for 4 and 24 h. After 4 or 24 h, larvae were collected for qPCR analysis. The relative gene expressions are presented as the ratio of the quantity of candidate gene/average quantity of housekeeping genes. A pool of 20 larvae per group (n = 3) was used. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. for three different experiments performed in triplicate. * p < 0.05, ** and ### p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 compared to the CuSO4 alone group.

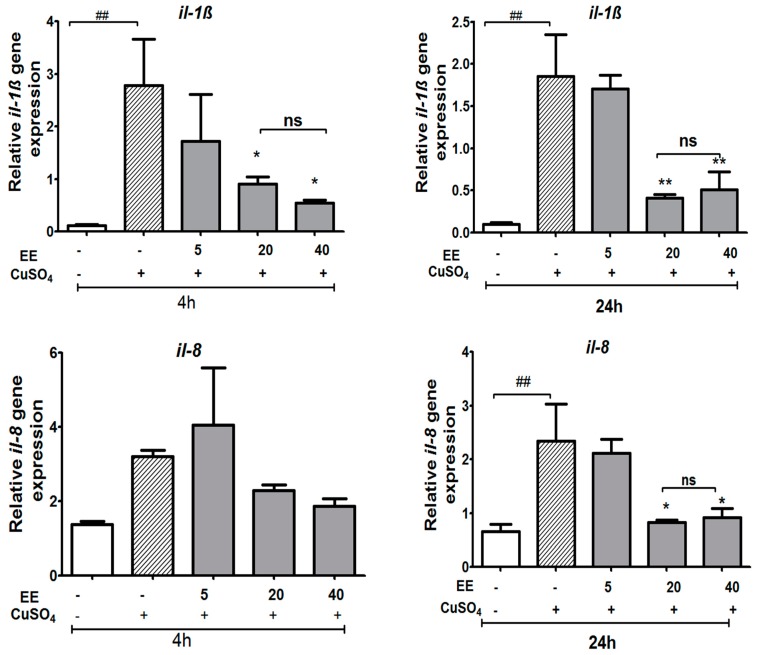

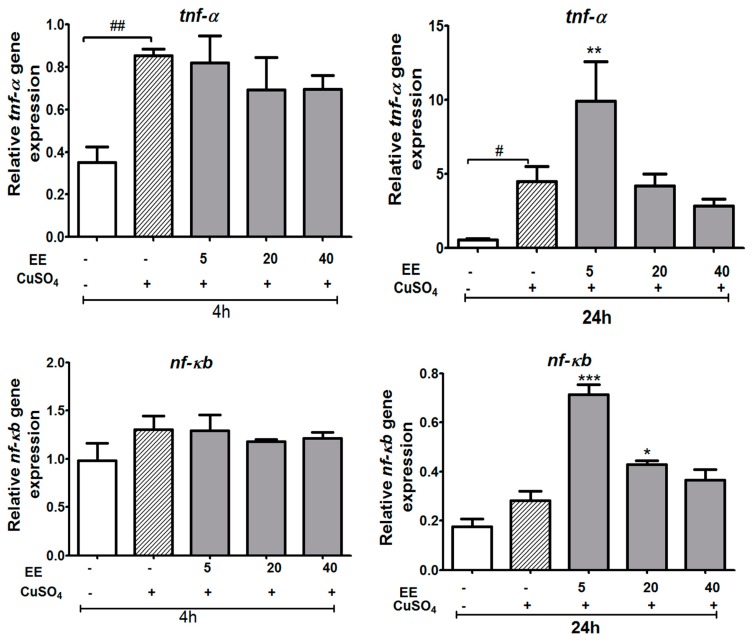

3.3.2. The EE Inhibited the Transcription of CuSO4-Induced Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Zebrafish Larvae

We examined whether the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine genes increased due to CuSO4 exposure and, subsequently, whether EE inhibits CuSO4-induced expression of tnf-α, il-1β, nf-ƙb, and il-8 at concentrations of 5, 20, and 40 µg/mL. Real-time RT-PCR analysis revealed that CuSO4 stimulated the inflammation process by a significant increase of il-1β and tnf-α expression at 4 and 24 h and il-8 levels at 24 h after copper sulfate exposure (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The co-administration of EE at the doses of 20 and 40 µg/mL resulted in a decrease in the mRNA levels of il-1β at both 4 and 24 h, and il-8 at 24 h (Figure 6). No significant differences were observed for the expression of nf-ƙb or tnf-α between the different treatment groups (Figure 7). These results suggest that the EE at concentrations of 20 and 40 µg/mL inhibited transcription activities of pro-inflammatory cytokines induced by CuSO4 in zebrafish larvae.

Figure 6.

Relative expression of genes involved in immune responses (il-1ß and il-8) of zebrafish larvae after exposure to CuSO4 and treatment with the ethanol extract (EE) of C. cyrtophyllum Turcz at different doses. The zebrafish larvae were exposed to EE for 1 h and to CuSO4 10 µM for 4 and 24 h. After 4 or 24 h, larvae were collected for qPCR analysis. The relative gene expressions are presented as the ratio of the quantity of candidate gene/average quantity of housekeeping genes. A pool of 20 larvae per group (n = 3) was used. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. for three different experiments performed in triplicate. * p < 0.05, ** and ### p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to the CuSO4 alone group.

Figure 7.

Relative expression of genes involved in immune responses (tnf-α and nf-ƙb) of zebrafish larvae after exposure to CuSO4 and treatment with the ethanol extract (EE) of C. cyrtophyllum Turcz at different doses. The zebrafish larvae were exposed to EE for 1 h and to CuSO4 10 µM for 4 and 24 h. After 4 or 24 h, larvae were collected for qPCR analysis. The relative gene expressions are presented as the ratio of the quantity of candidate gene/average quantity of housekeeping genes. A pool of 20 larvae per group (n = 3) was used. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. for three different experiments performed in triplicate. * p < 0.05, ** and ### p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 compared to the CuSO4 alone group.

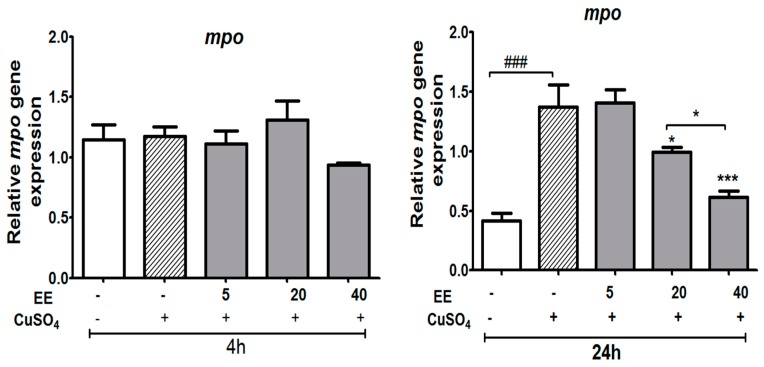

3.3.3. Effect of the Ethanol Extract (EE) of C. cyrtophyllum Turcz Leaves on Expression of the mpo Gene

Neutrophil migration, as indirectly measured by the mRNA level of mpo, displayed a significant increase after 24 h of exposure to copper sulfate. Exposing zebrafish larvae to EE resulted in a decrease in the mRNA levels of mpo at 20 and 40 µg/mL (p < 0.05) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Relative expression of genes involved in immune responses (mpo) of zebrafish larvae after exposure to CuSO4 and treatment with the ethanol extract (EE) of C. cyrtophyllum Turcz. The data are presented as mean ± S.E. for three different experiments performed in triplicate. * p < 0.05, ** and ### p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to the CuSO4 alone group.

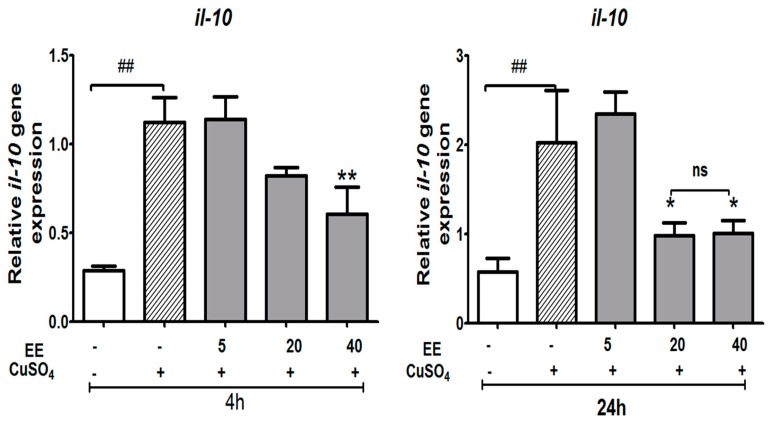

3.3.4. Effect of the Ethanol Extract (EE) of C. cyrtophyllum Turcz leaves on the Expression of Anti-Inflammatory Cytokine il-10

As shown in Figure 9, stimulating zebrafish larvae with CuSO4 increased the level of il-10 mRNA. Increased il-10 expression in response to CuSO4 stimulation alone showed the regulatory action on cells after the inflammatory reaction. The level of il-10 was significantly suppressed by EE at 40 µg/mL at 4 h, and at both 20 and 40 µg/mL at 24 h (p < 0.05). The level of il-10 decreased the most under the EE treatment condition, which illustrated the effect of EE on reinforcing cellular immunity and inhibiting humoral immunity.

Figure 9.

Relative expression of anti-inflammatory gene (il-10) of zebrafish larvae after exposure to CuSO4 and treatment with the ethanol extract (EE) of C. cyrtophyllum Turcz at different doses. The zebrafish larvae were exposed to EE for 1 h and to CuSO4 10 µM for 4 and 24 h. After 4 or 24 h, larvae were collected for qPCR analysis. The relative gene expressions are presented as the ratio of the quantity of candidate gene/average quantity of housekeeping genes. A pool of 20 larvae per group (n = 3) was used. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. for three different experiments performed in triplicate. * p < 0.05, ** and ### p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 compared to the CuSO4 alone group.

4. Discussion

4.1. Protective Activity of the Ethanol Extract of C. cyrtophyllum against CuSO4 Toxicity

Copper is an essential micronutrient but misregulation of intracellular levels can become toxic to many cell types. Copper generates dose-dependent responses. A previous study demonstrated that low concentrations of copper (<10 µM) did not induce mortality [16]. At the concentration of 10 μM, although it did not cause a significant decrease of zebrafish larvae survival, copper sulfate was able to induce oxidative stress and a marked increase of inflammatory markers [17]. A concentration of 25 μM induced a 75–80% death rate [18]. In the present study, CuSO4 at 20 µM induced 80% mortality after 24 h of exposure. Interestingly, treatment with EE at concentrations of 20 and 40 µg/mL showed a protective effect against damage induced by CuSO4.

What is the reason for this? Which molecular mechanism of EE helped zebrafish larvae to avoid the toxicity of copper? To better understand the protective mechanism of EE, the toxicity mechanism of copper in zebrafish larvae first needs to be identified.

It was suggested recently that copper induces oxidative stress [16,18]. Oxidative stress can occur by two mechanisms: the direct effect of copper, which induces DNA and cell damage, or the increase of ROS release due to the activation of phagocytic cells and increased tissue damage [13]. The increase of ROS release might induce the activation of activator protein-1 (AP-1) and nuclear factor kappa-B (Nf-κB), both signaling pathways that upregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines leading to inflammation. Inflammation represents the result of copper damage. Both oxidative stress and inflammation are related to the toxicity mechanism of copper. We thus investigated the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of EE.

4.2. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of the Ethanol Extract of C. cyrtophyllum

To evaluate the antioxidant activity, we first used an in vitro test, the DPPH assay. DPPH radical scavenging assay is one of the most common methods used to evaluate the radical scavenging activity of antioxidants because of its speed, reliability, and reproducibility. A change in color from purple to yellow indicates a decrease in absorbance of DPPH radicals. This demonstrates that an antioxidant present in a solution is interacting with the free radicals [11]. In this study, EE exhibited strong antioxidant properties against 1,1-diphenyl,2-picryl hydrazyl (DPPH), with an IC50 value of 16.45 ± 1.11 µg/mL. The antioxidant activity of EE found here was stronger than that reported by Liu et al. (2011) for a methanol extract of C. cyrtophyllum (52.74 ± 2.07 µg/mL) [9]. This can be explained by the fact that flavonoids are important antioxidants due to their high redox potential, which allows them to act as reducing agents, hydrogen donors, and singlet oxygen quenchers [19]. Antioxidant activity was correlated with total flavonoids. The higher is the content of flavonoids, the stronger is the antioxidant capacity in vitro. In our study, EE was found to present higher flavonoid contents than the methanol extract reported by Liu et al. [9]. Another antioxidant mechanism of flavonoids may result from the interactions between flavonoid and metal ions (especially iron and copper) leading to chelates formation that are only slightly active in the promotion of free-radical reaction. In our study, EE can chelate copper, decreasing the toxicity of CuSO4. However, the copper chelating ability of EE is weak. It did not appear as a major mechanism for protective activity of the ethanol extract of C. cyrtophyllum against CuSO4 toxicity.

Although the in vitro model is simple, fast, and inexpensive, it cannot be a complete substitute for in vivo animal testing. The absence of biokinetics in in vitro methods may lead to a misinterpretation of the data. Animal models thus are more reliable than in vitro tests [20]. Among animal models, zebrafish display several pathological features similar to those of humans [21]. In this study, we used a zebrafish model to confirm the antioxidant effects of EE, as well as to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of its antioxidant activity.

There are two main mechanisms of drug-induced oxidative stress: an increase in ROS production and a reduction of cellular antioxidant genes. We thus examined the effects of EE on ROS production as well as on the expression of antioxidant genes.

Regarding ROS production, the image analysis in stress-induced ROS generation showed that copper sulfate induced toxicity in the cells via the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). EE displayed a protective effect against stress in vivo by reducing ROS formation in zebrafish larvae. Regarding the expression of antioxidant genes, in our study, sod was decreased significantly after 4 h of exposure to copper when compared to control, while groups that were treated with CuSO4 plus EE at 20 and 40 µg/mL resulted in a significant increase of mRNA levels of sod when compared with the CuSO4 group. Increasing superoxide dismutase (SOD) helps to transfer ROS to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which then forms a non-toxic compound (H2O) under the effects of catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and peroxidase.

Major cytotoxic roles for ROS include the activation of the apoptosis pathway [22]. Heat shock proteins are one of the key players in protecting the cell against the harmful effects of oxidative stress in the cellular stress response process and are crucial for defending cells from copper toxicity [16]. Our results are similar to those previously reported where copper induces hsp70 expression [16]. Interestingly, expression of hsp70 decreased in the EE treatment groups. This result suggests that the presence of EE helped to protect zebrafish larvae against CuSO4 toxicity, reducing oxidative stress and damage. As a result, the expression of hsp70 decreased.

Gadd45 participates in cell growth and cell cycle control, DNA repair, apoptosis, maintenance of genomic stability, and the regulation of signaling pathways. Transcription of the gadd45 genes is induced by DNA-damaging agents and other cellular stresses and is associated with growth arrest [23,24]. Olivari et al. (2008) described events induced by copper via oxidative stress, such as cell death by apoptosis and necrosis in hair cells of the lateral line of zebrafish [13]. Supporting these data, our results show that copper induced activation of the apoptosis pathway in such a way that mRNA expression level of gadd45bb was significantly upregulated. EE can scavenge superoxide anions, inhibit ROS production, and defend cells from copper toxicity, decreasing cellular stresses, apoptosis, and DNA-damage. As a result, the expression of gadd45bb was downregulated compared to the CuSO4 alone group.

Intracellular production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is deeply involved in inflammatory responses. High levels of redox metals promote ROS formation and these metals can also act as mediators of inflammation, inducing peripheral inflammation in numerous models [25]. Leite et al. (2013) reported the gradual accumulation of copper in zebrafish larvae within 24 hpf; increased activity of NO; upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine-related genes il-1β, tnf, and cox-2; and increased PGE2 and myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels, which are also known for their activity as inflammatory players [18]. Similar to previous studies, our data also show that copper induced inflammation through the upregulation of cox-2, il-1β, tnf-α, mpo, pla2, il-8, c3a, and il-10. Altogether, this study provides more evidence on the effects of copper as well as on the general scenario of the inflammatory status and response to copper exposure that corroborates copper’s role in oxidative stress and inflammation.

The expression of cox-2, pla2, c3a, il-1ß, and il-8 decreased in the EE treatment groups. COX-2 and PLA2 are involved in the synthesis of key biological mediators in inflammation. Inhibition of these enzymes is a well-established target in the discovery of anti-inflammatory drugs, with COX-inhibitors being the most prominent drug class in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Flavonoids play an important role in various medicinal applications. C. cyrtophyllum leaves present high flavonoid contents [8,9]. Flavonoids have been reported to inhibit the activities of arachidonic acid metabolizing enzymes such as PLA2, COX, and 5-LOX, to reduce the production of inflammatory metabolites from arachidonic acid and oxidative damage [26]. IL-1ß and IL-8 are pro-inflammatory cytokines. There is abundant evidence that certain pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-2, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and IFN-γ are involved in the process of pathological inflammation. Because of this, the cytokine system constitutes a very interesting target for the development of clinically relevant anti-inflammatory drugs. In this study, EE effectively inhibited the production of il-1ß and il-8 at both 20 and 40 µg/mL by suppressing their mRNA expression in CuSO4-stimulated zebrafish larvae. This result demonstrates that EE effectively inhibits the generation of an inflammatory response. However, the level of TNF-α transcription was not affected by EE at 4 h. At 24 h, expression of tnf-α even increased at the dose of 5 µg/mL. Increased expression of tnf-α can explain the weak anti-inflammatory activity of EE at 5 µg/mL.

The regulation of inflammatory gene transcription is controlled by specific signaling pathways and transcription factors, such as NF-κB and AP-1. In response to stimulation, NF-κB is liberated from a complex with I-κB and induces transcription of inflammatory genes that cause acute inflammation and a systemic inflammatory response syndrome [27]. In this study, CuSO4 did not increase the expression of nf-κb. This result demonstrates that nf-κb did not regulate the inflammatory gene transcription stimulated by CuSO4. The increase expression of inflammatory genes due to CuSO4 can relate to other transcription factors with other signaling pathways that need further studies. The ethanol extract from C. cyrtophyllum had no effect on the expression of nf-κb at 4 h; however; expression of nf-κb increased at the dose of 5 and 20 µg/mL at 24 h. In our previous study, EE alone had no effect on the expression of nf-κb. Increasing its expression when association with CuSO4 may be related to another function of nf-κb. The association of NF-kB activity and inflammatory disease is not easy to interpret because both pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators are produced during inflammation [28]. In 2001, Lawrence et al. [29]. showed NF-kB involves in both the onset and resolution of acute inflammation in a single model system using pharmacological inhibitors. These studies confirmed the role of NF-kB in proinflammatory gene induction but also showed a role for NF-kB in the expression of anti-inflammatory genes during the resolution of inflammation [29]. Thus, increasing expression of nf-κb at the dose of 5 and 20 µg/mL at 24 h may be related to resolution function of NF-kB in a cute inflammation.

However, the increase in mRNA levels is not directly proportional to the amount of protein translated, due to transcriptional and post translational modifications. Although no significant differences in the mRNA levels of tnf-α and nf-κb at 4 h or increase of the expression of these genes at 24 h was observed, further studies are required in order to investigate the expression at the protein level and to verify the presence and activation of these proteins.

Recently, d’Alencon et al. demonstrated that copper sulfate exposure induces neutrophil migration to the inflammatory focus, in response to damage induced in hair cells of the lateral line of zebrafish larvae [30]. Activated neutrophils, monocytes, and some tissue macrophages release MPO at the site of inflammation. MPO catalyzes the reaction between hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and physiological halides (such as Cl−) to form reactive oxidants such as hypochlorous acid (HOCl) [31]. In this study, EE effectively inhibited the expression of mpo at 20 and 40 µg/mL at 24 h. This suggests that EE has an anti-inflammatory role through the inhibition of leukocyte infiltration.

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a cytokine with potent anti-inflammatory properties that plays a central role in limiting the host immune response to pathogens, thereby preventing damage to the host and maintaining normal tissue homeostasis. IL-10 is a molecule that displays both immunostimulatory and immunoregulatory activities [32]. IL-10 can up-regulate endogenous anti-cytokines and down-regulate pro-inflammatory cytokine receptors to dampen uncontrolled production of inflammatory cytokines and excessive inflammation during infection [33]. In this study, stimulation of zebrafish larvae with CuSO4 increased the level of il-10 mRNA at 4 and 24 h after exposure. The elevation of il-10 displayed immunoregulatory activity on cells after the inflammatory reaction [18]. Co-administration with EE at 20 and 40 µg/mL down-regulated il-10. Supporting these data, a previous study conducted by Visser et al. (1998) revealed that elevated il-10 levels were also observed in an LPS-induced inflammatory model in peritoneal macrophages, demonstrating similarities of modulation mechanisms in these two models [34].

4.3. The Relation between Dose and Response

In most cases, EE displayed an effect on gene expression depending on the dose. At the low dose of 5 µg/mL, EE generally exerted no detectable effects. However, at 20 µg/mL, EE showed a higher effect. Interestingly, the anti-inflammatory property of EE not only depends on the dose but also on the time. At 4 h, EE at 20 µg/mL indicated no effects or low effect on the inhibition expression of inflammatory genes. However, this effect increased at 24 h. One possible explanation could be that, as exposure to the extract is prolonged over time, there is an increase in the accumulation of the extract until it reaches a concentration that induces anti-inflammatory effects in zebrafish. At the highest dose of 40 µg/mL, EE induced the best effects at both 4 and 24 h.

4.4. The Potential Area of Application of EE

The results of this study suggest that the ethanol extract of C. cyrtophyllum leaves possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. They provide some evidence for the use of the plant extract in the prevention as well as treatment of oxidative stress and inflammatory conditions. However, before applying EE in treatment human diseases, we still need to do experiments in other models to confirm the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of EE. We also need to perform additional experiments to determine whether EE is safe for testing in human subjects; preclinical toxicology studies need to be performed to identify the treatment regimen associated with the least degree of toxicity and thus determine a suitable and safe starting dose for clinical trials.

5. Conclusions

The ethanol extract of C. cyrtophyllum displayed prominent antioxidant effects through radical scavenging activity in vitro and decreased production of ROS in a CuSO4-induced zebrafish inflammation model. In addition, in vivo results in zebrafish suggest that the ethanol extract from C. cyrtophyllum also inhibits oxidative stress via the upregulation of sod and the downregulation of hsp70 and gadd45bb. EE also inhibited inflammation via the downregulation of the inflammatory genes cox-2, pla2, c3a, il-1, il-8, mpo, and il-10. These in vivo results help to elucidate the protective mechanism against CuSO4 toxicity of the ethanol extract of leaves of C. cyrtophyllum. Taken together, these findings provide a pharmacological basis for the use of C. cyrtophyllum leaves in the treatment of inflammatory disorders.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by ARES (Académie de Recherche et d’Enseignement Supérieur) and DGD (Direction Générale de la Coopération au Développement) through the funding of the project “Exploring the Medical and (Eco)-toxicological Potential of Natural Extracts in North Vietnam”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H.N. and P.K.; Methodology, T.H.N., T.M.N., H.D.L., T.N.T.K., V.C., and J.L.; Validation, P.K. and H.D.L.; Formal analysis, T.H.N. and T.M.N.; Investigation, T.H.N., T.M.N., H.D.L., T.N.T.K., V.C., and J.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, T.H.N.; Writing—Review and editing, P.K., T.M.N., H.P.T., and T.N.T.K.; Supervision, P.K.; and Project Administration, P.K. and H.P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ARES (Académie de Recherche et d’Enseignement Supérieur) and the Ministry of Cooperation (DGD (Direction Générale de la Coopération au Développement)) in Belgium.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Biswas S.K. Does the Interdependence between Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Explain the Antioxidant Paradox? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/5698931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fialkow L., Wang Y., Downey G.P. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species as signaling molecules regulating neutrophil function. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;42:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes P.J., Karin M. Nuclear factor-kB—A pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakraborty C., Hsu C., Wen Z., Lin C., Agoramoorthy G. Zebrafish: A Complete Animal Model for In Vivo Drug Discovery and Development. Curr. Drug Metab. 2009;10:116–124. doi: 10.2174/138920009787522197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira T.C.B., Campos M.M., Bogo M.R. Copper toxicology, oxidative stress and inflammation using zebrafish as experimental model. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2016;36:876–885. doi: 10.1002/jat.3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nhuong L.C., van Long N., Hoa N.D. Chemical constituents and antioxidant activity of flavonoids from Clerodendron cyrtophyllum Turcz. Vietnam. Pharm. J. 2006;46:30–33. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kar P., Goyal A.K., Das A.P., Sen A. Antioxidant and pharmaceutical potential of Clerodendrum L.: An overview. Int. J. Green Pharm. 2014;8:210–216. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J., Zheng X., Yang Q., Liang Z., Li D., Yang X., Xu J. Optimization of Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction and Radical-Scavenging Capacity of Phenols and Flavonoids from Clerodendrum cyrtophyllum Turcz Leaves. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu H., Wang L., Wang M. Antioxidant and Nitric Oxide Release Inhibition Activities of Methanolic Extract from Clerodendrum cyrtophyllum Turcz. Hort. Environ. Biotechnol. 2011;52:309–314. doi: 10.1007/s13580-011-0204-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lackmann C., Martinez M., Rainieri S., Barranco A., Hollert H., Spirhanzlova P., Velki M., Seiler T. Chemosphere Novel procedures for whole organism detection and quantification of fluorescence as a measurement for oxidative stress in zebrafish (Danio Rerio) larvae. Chemosphere. 2018;197:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C.Z., Yuan H.H., Bao X.L., Lan M.B. In vitro antioxidant and cytotoxic properties of ethanol extract of Alpinia oxyphylla fruits. Pharm. Biol. 2013;51:1419–1425. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2013.794844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santos J.S., Brizola V.R.A., Granato D. High-throughput assay comparison and standardization for metal chelating capacity screening: A proposal and application. Food Chem. 2017;214:515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olivari F.A., Hernández P.P., Allende M.L. Acute copper exposure induces oxidative stress and cell death in lateral line hair cells of zebrafish larvae. Brain Res. 2008;1244:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S.H., Ko C.I., Jee Y., Jeong Y., Kim M., Kim J.S., Jeon Y.J. Anti-inflammatory effect of fucoidan extracted from Ecklonia cava in zebrafish model. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;92:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bio-Rad . Real-Time PCR Applications Guid. Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.; Hercules, CA, USA: 2006. Real-Time qPCR Data Analysis; pp. 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez P.P., Undurraga C., Gallardo V.E., Mackenzie N., Allende M.L., Reyes A.E. Sublethal concentrations of waterborne copper induce cellular stress and cell death in zebrafish embryos and larvae. Biol. Res. 2011;44:7–15. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602011000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cruz F.F., Leite C.E., Kist L.W., de Oliveira G.M., Bogo M.R., Bonan C.D., Campos M.M., Morrone F.B. Effects of caffeine on behavioral and inflammatory changes elicited by copper in zebrafish larvae: Role of adenosine receptors. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017;194:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leite C.E., de Oliveira Maboni L., Cruz F.F., Rosemberg D.B., Zimmermann F.F., Pereira T.C.B., Bogo M.R., Bonan C.D., Campos M.M., Morrone F.B., et al. Involvement of purinergic system in inflammation and toxicity induced by copper in zebrafish larvae. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013;272:681–689. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babbar N., Oberoi H.S., Sandhu S.K. Therapeutic and Nutraceutical Potential of Bioactive Compounds Extracted from Fruit Residues. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015;55:319–337. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.653734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saeidnia S., Manay A., Abdollahi M. From in vitro Experiments to in vivo and Clinical Studies; Pros and cons. Curr. Drug Discov Technol. 2015;12:218–224. doi: 10.2174/1570163813666160114093140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang L.L., Wang G.Q., Yang L.M., Huang Z.B., Zhang W.Q., Yu L.Z. Endotoxin molecule lipopolysaccharide-induced zebrafish inflammation model: A novel screening method for anti-inflammatory drugs. Molecules. 2014;19:2390–2409. doi: 10.3390/molecules19022390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhai Q., Ji H., Zheng Z., Yu X., Sun L., Liu X. Copper induces apoptosis in BA/F3β cells: Bax, reactive oxygen species, and NFκB are involved. J. Cell. Physiol. 2000;184:161–170. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200008)184:2<161::AID-JCP3>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moskalev A.A., Smit-McBride Z., Fraifeld V.E. Gadd45 proteins: Relevance to aging, longevity and age-related pathologies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2012;11:51–66. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu B., Zhang Y.H., Jiang Y., Li L.L., Chen Q., He G.Q., Tan X.D., Li C.Q. Gadd45b is a novel mediator of neuronal apoptosis in ischemic stroke. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2015;11:353–360. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.9813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choo X.Y., Alukaidey L., White A.R., Grubman A. Neuroinflammation and copper in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/145345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S., Pandey A.K. Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview. Sci. World J. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/162750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu S.F., Malik A.B. NF-kB activation as a pathological mechanism of septic shock and inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2006:622–645. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00477.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence T. The Nuclear Factor NF-kB Pathway in Inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009:a001651. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawrence T., Gilroy D.W., Colville-Nash P.R., Willoughby D.A. Possible new role for NF-κB in the resolution of inflammation. Nat. Med. 2001;7:1291–1297. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Alencon C.A., Pena O.A., Wittmann C., Gallardo V.E., Jones R.A., Allende M.L. A high-throughput chemically induced inflammation assay in zebrafish. BMC Biol. 2010;8:151. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan A., Alsahli M., Rahmani A. Myeloperoxidase as an Active Disease Biomarker: Recent Biochemical and Pathological Perspectives. Med. Sci. 2018;6:33. doi: 10.3390/medsci6020033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harizi H., Gualde N. Pivotal role of PGE2 and IL-10 in the cross-regulation of dendritic cell-derived inflammatory mediators. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2006;3:271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J.M., An J. Cytokines, Inflammation and Pain. Int. Anesth. Clin. 2007;45:27–37. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e318034194e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Visser J., van Boxel-Dezaire A., Methorst D., Brunt T., De Kloet E.R., Nagelkerken L. Differential regulation of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-12 by glucocorticoids in vitro. Blood. 1998;91:4255–4264. doi: 10.1182/blood.V91.11.4255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]