Abstract

Objective:

To test reciprocal associations among internalizing symptoms (depression and social anxiety), using alcohol and cannabis to cope, and use-related problems.

Method:

The study utilized a community sample (N=387, 55% female; majority non-Hispanic Caucasian (83.1%) or African American (9.1%)) and a longitudinal design that spanned 17 to 20 years of age, and distinguished within- and between-person associations using latent curve models with structured residuals.

Results:

Reciprocal prospective within-person associations were supported for alcohol, such that elevated depression symptoms were associated with increased alcohol coping motivates one year later, which in turn, was associated with subsequent increased depression symptoms. Bidirectional associations were not supported for social anxiety, although high levels of social anxiety were associated with elevated levels of coping drinking one year later. Cannabis coping motives were associated with exacerbation of depression, but not social anxiety symptoms, one year later. Between- and within-person contemporaneous associations suggested that depression and social anxiety were more strongly associated with coping than social/enhancement motives, and that coping motives were associated with use related problems.

Conclusion:

Findings suggest that alcohol coping motivates exacerbate rather than ameliorate depression symptoms, which in turn, leads to greater reliance on alcohol to cope. There was more consistent support for associations with substance use-related problems for depression than for social anxiety. Both between- and within-person associations may be useful for identifying targets and timing of coping-oriented interventions.

Keywords: Adolescent substance use, emotional distress, coping, cannabis, alcohol

Public Health Statement:

Study findings suggest that emotional distress can lead to strong motivations to drink alcohol to cope, which, in turn, leads to exacerbation of emotional distress. This was not found for cannabis use, although using both cannabis and alcohol to cope was associated with use-related problems. Stable trait-like levels of coping motivated use as well as transient increases may be a useful variable to identify substance users who are most likely to benefit from coping skills intervention.

Internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, social withdrawal) are considered a risk factor for adolescent substance use (Colder, Chassin, Lee, and Villalta, 2010), and self-medication and coping theories are often invoked as explanatory mechanisms for this risk pathway. According to these theories, substance use is motivated by efforts to ameliorate emotional distress and this implies that elevated emotional distress motivates subsequent use. Yet, also plausible is that substance use exacerbates emotional distress. Wills and Shiffman (1985) noted that although using alcohol and drugs to cope with distress may provide short-term relief, reliance on this coping strategy is likely to interfere with adopting alternative adaptive coping, and exacerbation of emotional distress. Accordingly, coping motivated substance use is expected to result in continued emotional distress and escalation of substance use and use-related problems.

Although reciprocal associations are expected between internalizing symptoms and substance use, findings from prior research have been notably inconsistent, particularly with respect to adolescent substance use. In this study, we examined reciprocal associations between internalizing symptoms and substance use using a longitudinal design, and addressed three issues that likely contribute to inconsistent patterns of associations in the literature for adolescent and young adult samples. These issues include considering coping motivated use (rather than general use), statistically controlling for externalizing symptoms (e.g., aggression and rule breaking behavior), and separating between- and within-person associations. We focused on alcohol and cannabis because these are among the most commonly used substances (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, and Schulenberg, 2017). Furthermore, internalizing symptoms represent a variety of symptom clusters; we focused on depression and social anxiety symptoms, because these symptom clusters have shown the most robust associations with substance use (Colder et al., 2010; Hussong, Ennett, Cox, & Haroon, 2017).

Coping Motives

Consistent with the idea that alcohol and cannabis use are motivated to ameliorate emotional distress, some studies find that internalizing symptoms are prospectively associated with increases in alcohol and cannabis use (Parrish, Atherton, Quintana, Conger, & Robins, 2016; Stapinski, Montgomery, & Araya, 2016). Yet, other studies suggest that internalizing symptoms are negatively related to alcohol and cannabis use (Kaplow, Curran, Angold, & Costello, 2001; Farmer et al., 2015), perhaps because the fearfulness, social withdrawal, and avoidance that characterize internalizing symptomology protect youth from selecting into peer groups that support substance use (Fite, Colder, & O’Connor, 2006). Other research finds no association between internalizing symptoms and adolescent alcohol and cannabis use (e.g., Danielsson, Lundin, Agardh, Allebeck, & Forsell, 2016; Hussong, Curran, & Chassin, 1998; Meier, Hill, Small, & Luther, 2015; Miller-Johnson, Lochman, Coie, Terry, & Hyman, 1998). One possible reason for these mixed findings may be that adolescents engage in alcohol and cannabis use for many reasons, and internalizing symptoms are expected to be associated specifically with coping motived use. Hence, examining coping motivated use, rather than general use, may help clarify the link between internalizing symptoms and alcohol and cannabis use. Indeed, there is evidence from both cross-sectional and prospective studies that elevated levels of internalizing symptoms are associated with frequent use of alcohol and cannabis for coping reasons (e.g., Blevins, Banes, Stephens, Walker, & Roffman, 2016; Ehrenberg, Armeli, Howland, & Tennen, 2016; Kuntsche, Knibbee, Gmel, & Engels, 2005; Lee, Neighbors, & Woods, 2007; Simons, Correia, Carey, & Borsari, 1998; Zvolensky et al., 2007).

With respect to reciprocal associations, there is evidence that high levels of alcohol and cannabis use prospectively predict increases in internalizing symptoms (Jun, Sacco, Bright, & Camlin, 2015; Lev-Ran, et al., 2014; Parrish et al., 2016), but this has not been consistently supported (Frӧjd, Ranta, Kaltiala-Heino, & Marttunen, 2011; Scholes-Balog, Hemphill, Evans-Whipp, Toumbourou, & Patton, 2016). Again, these associations may be more consistent for coping motivated use, but not many studies have examined whether coping motivated substance use prospectively predicts internalizing symptoms. Blevins et al. (2016) found that using cannabis frequently for coping reasons was associated with elevated levels of internalizing symptoms above and beyond general frequency of use, but this study was cross-sectional making it difficult to establish temporal precedence. Armeli, Sullivan, and Tennen (2015) used a burst design that included daily assessments and found that increases in coping motivated drinking predicted subsequent increases in both anxiety and depression symptoms. We are unaware of studies that have similarly tested social anxiety or studies that have considered whether cannabis coping motives prospectively predict internalizing symptoms. The current study addresses these gaps in the literature.

Externalizing Symptoms

There is ample evidence that externalizing and internalizing symptoms covary (e.g., Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), which suggests the importance of statistically controlling for externalizing symptoms when testing associations between internalizing symptoms, substance use, and substance use motives. This is rarely done (Colder et al., 2010); when externalizing symptoms are included, the associations between internalizing symptoms and substance use are often diminished substantially, or may even change sign (Colder et al., 2018; Hussong et al., 2017). In the current study, we include externalizing symptoms as a statistical control variable to account for its potentially confounding effects.

Between- and Within-Person Associations

Substance use to cope with emotional distress is considered a reactive process, and thus coping motivations should ebb and flow as life circumstances change (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Cooper et al., 2008; Cox & Klinger, 2011). Similarly, internalizing symptoms vary within individuals across time (de Vries, Dijkman-Caes, & Delespaul, 1990; Nezlek, 2002; Star & Davila, 2012), and presumably the motivation to use substances to cope increases as emotional distress increases. Likewise, an individual using alcohol or cannabis to cope at a given point in time would be expected to experience subsequent exacerbation of internalizing symptoms in the long run (Wills and Shiffman, 1985). Taken together, these reactive processes suggest the importance of considering within-person or time-specific associations. Furthermore, failure to disaggregate between- and within-person associations can lead to misrepresentation and bias in associations (Hoffman & Stawski, 2009). In fact, between- and within-person associations can be quite different, even of opposite signs. A number of studies have considered within-person associations between coping motives and internalizing symptoms (e.g., Arbeau, Kuiken, & Wild, 2011; Armeli et al., 2014; 2015; Ehrenberg et al., 2016; Hussong, 2007; Littlefield, Jackson, & Talley, 2012) and we extend this work in several important ways. First, to our knowledge, no studies have included social anxiety and coping motives in a model that disaggregates between-and within-person associations, and this is a notable omission given the relevance of social anxiety in coping models (Buckner, Heimberg, Ecker, & Vinci, 2012). Second, we are aware of no studies that have considered these associations with respect to cannabis coping motives. The current study addresses these gaps in the literature.

Third, work examining coping motives that has disaggregated between and within-person (or time-specific) associations has utilized burst designs and examined daily or weekly associations. These designs are useful for understanding immediate reactive processes relevant to coping motivated substance use, but they do not offer any insight into long-term developmental sequela of an internalizing pathway. The literature provides clear evidence that, after initiation, there is significant variability in the escalation of adolescent substance use that progresses to heavy use and disorder for a small proportion of youth (Brown et al. 2008). This progression often occurs over the span of years (Marel et al., 2018; Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011). Typical age of initiation of alcohol and cannabis use is in middle adolescence (between 13–15 years) whereas the onset of disorder is late adolescence and young adulthood. These epidemiological findings suggests the utility of long-term prospective designs over multiple years and that late adolescence corresponds to a critical period when youth approach peak periods of problem use. Short-term intensive burst designs do not provide any insight into how coping motivated substance use may influence developmental trajectories, nor do they permit one to examine within-person associations in the context of the emergence and escalation of substance use. Our study addresses this gap by examining between- and within-person associations during this important period of late adolescence using three annual assessments. This design permits examination of growth over multiple years, as well as reciprocal within-person associations between coping motivated use and internalizing symptoms.

In the context of our study with annual assessments one has to consider reactive processes involving events that might influence behavior over long time spans, rather than reactive processes that might operate in a smaller scale of time (e.g., minute to minute or day to day). Adolescence is a time of transition when youth establish independence from their family, and experiment with adult roles and new identities in the service of establish independence and a stable sense of self (Steinberg and Morris, 2001). During this period youth begin to establish romantic relationships, explore sexuality, form friendships that are emotionally close and reciprocally supportive, renegotiate relationships with adults, and meet the demands of increasingly mature roles and responsibilities that may include entering the work force and formulating long-term life goals. These challenges can be stressful (Spear, 2000) and often accompanied by intense emotional experience (e.g., Larson, Moneta, Richards, & Wilson, 2002; Petersen et al., 1993). Both minor and major stressors are associated with emotional distress in adolescence in the short and long-term (Baer, Garmezy, McLaughlin, Pokorny, & Wernick, 1987; Flook, 2011; Brooks-Gunn & Warren, 1989; Compas, 1987). King, Molina, and Chassin (2008) argued that stress levels can vary across individuals but also within an individual across time. These authors used sophisticated state-trait error model to show that stress was best characterized by both stable time-invariant component and annually time-varying component. To the extent that distress drives coping motivated substance use (and vice versa), coping motivated substance use should fluctuate from year to year. In short, there are conceptual reasons when considering the developmental context of adolescence as well as indirect support for notion that coping motivated use would vary year to year. Consistent with this idea, Armeli, Connor, Covault, Tennen, and Kranzler (2008) used four annual assessments in a college sample and found that drinking to cope was elevated in years characterized by elevations in life stress. In a more recent study, Armeli, Covault, & Tennen (2018) found that levels of drinking to cope in college predicted alcohol-related problems five years post college. Littlefield, Sher, and Wood (2010) utilized a longitudinal sample that included seven assessment spanning ages 18 to 35 and found that increases in coping motivated drinking were associated with escalation in alcohol-related problems. These studies suggest the utility of long-term longitudinal designs to understand the developmental sequela of coping motivated substance use and support the utility of our longitudinal design to examine both growth trajectories as well as reciprocal within-person (or time-specific) associations relevant to coping motivates substance use.

The Current Study

In the current study, we used a community sample and a longitudinal design to test reciprocal associations between internalizing symptoms and frequency of using alcohol and cannabis to cope with emotional distress, and addressed several limitations of prior research. First, we focused on frequency of using alcohol and cannabis for coping reasons rather than general substance use. Second, we statistically controlled for externalizing symptoms. Third, we distinguished between- and within-person associations using latent curve models with structured residuals (LCM-SR; Curran, Howard, Bainter, Lane, & McGinley, 2014) with assessments that span three annual assessments during late adolescence. We expected that elevated internalizing symptoms would predict subsequent increases in coping motivated substance use, and that coping motivated substance use would predict subsequent increases in internalizing symptoms. Social and enhancement substance use motives were included as statistical control variables so that we could examine associations with coping motives above and beyond these other substance use motivations. Finally, we considered alcohol and cannabis use-related problems because some evidence suggests that coping motives are more strongly associated with use-related problems than with use (Cooper, Kuntsche, Levitt, Barber, & Wolf, 2016; Kuntsche et al., 2005). Although the majority of youth in a community sample are not expected to transition to problem use (Brown et al., 2008), our study is well suited to examine normal developmental processes that can lead to negative, albeit subclinical levels of problems.

Method

Participants

Data for this study were taken from a community sample of 387 adolescents and their caregivers recruited from households in Western NY assessed annually for nine years. The sample was recruited between April 2007 and February 2009. Adolescents were eligible for the study if they were between the ages of 11 and 12 at recruitment, and did not have any disabilities that would preclude them from either understanding or completing the assessment. Average age at the first assessment was 12 years old. The sample was approximately evenly split on gender (55% female at W1) and was predominantly non-Hispanic Caucasian (83.1%) or African American (9.1%). Median family income at first assessment was $70,000 and 6% of the families received public assistance income. These sample demographics compared well to demographics of families within our sampling frame, which was Erie County, NY (see Scalco, Trucco, Coffman, & Colder, 2015; Trucco, Colder, Wieczorek, Lengua, & Hawk, 2014 for more information on recruitment and sample description).

Procedure

For the current study, we focused on our final three waves of data: Wave 7 (W7), Wave 8 (W8) and Wave 9 (W9) because this is when alcohol and cannabis motives were assessed. After consent (caregiver) and assent/consent (depending on the age of the adolescent), the adolescent and caregiver were taken to separate rooms to complete the assessments. At each wave, caregivers were compensated $40 and adolescents were compensated $125. At W7, adolescents were on average 17.9 years old and 55% were attending college.

Retention was good for all waves (91% at W7-W9). Few demographic and W1 variables (e.g., cannabis and alcohol use) were associated with attrition, and those differences that did emerge are small (Colder et al., 2018; Colder et al., 2014). Furthermore, our data analytic approach utilized full-information likelihood estimation, which allowed us to include participants with missing data. Given the high retention rate, small differences, and our data analytic strategy, there is no reason to indicate that the findings were influenced by missing data.

Because motives are only relevant for users, participants were excluded if they abstained from use at all three assessments (W7-W9). Between W7 and W9, 51 participants reported no alcohol use and were excluded from analysis of alcohol use and motives, and 123 reported no cannabis use and were excluded from analysis of cannabis use and motives. The study was approved by University at Buffalo Internal Review Board.

Measures

Substance Use.

The number of drinks of alcohol per drinking day was computed from a weekly drinking calendar that asked participants to report the number of drinks consumed on each day of the week in a typical week from the past 90 days (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). A drink was defined as 12 ounces of beer, 1 wine cooler (12 oz.), 1 glass of wine (4 oz.), 1 shot of liquor (1 ¼ oz.), or 1 mixed drink. The average number of drinks was computed across drinking days to represent drinks per drinking day. We also computed number of drinking days per typical week for descriptive purposes. Past year frequency of cannabis use was reported using eight response options. Responses were converted to days in the past year to increase interpretability (e.g., not all = 0 days, once or twice = 1 day, once a month = 12 days, 2–3 days/month = 24 days, 4 or 5 days/week = 48 days, everyday = 365 days). Quantity of cannabis use was not assessed. Between 47% to 52% reported at least monthly marijuana use across the three assessments.

Substance Use Motives.

At each wave, the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ, Cooper, 1994) and the Marijuana Motives Questionnaire (MMQ, Simons, Correia and Carey, 2000) were used to assess use motives. Participants were asked to “think of all the times you use alcohol/marijuana, how often would you say that you use alcohol/marijuana for the following reasons?” Response options were 1=almost never/never, 2=some of the time, 3=half of the time, 4=most of the time, 5=almost always/always. Three subscales were taken from the DMQ and MMQ. The first subscale, coping motives, comprised five items and demonstrated good internal consistency at each wave for both alcohol and marijuana scales (α range: = .81 – .91). The other two scales were the social and enhancement motives subscales, which were included as statistical control variables in our analysis. Social motives and enhancement motives were strongly correlated at each wave (rs = .63 – .74), and so we combined these scales for analysis as has been done in past research (e.g., Armeli et al., 2008; Littlefield et al., 2012). This helped reduce the complexity of our models. The resulting social/enhancement motives scale had good internal consistency across waves for both alcohol and marijuana (α range: =.91 – .93).

Substance Use Problems.

The Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006) and The Marijuana Adult Consequences Questionnaire (MACQ; Simons, Dvorak, Merrill & Read, 2012) were used to assess use-related problems at each Wave. Items were summed to form scale scores for alcohol and marijuana problems. Internal consistency for both scales at each wave was very good (α range: = .91 – .95).

Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms.

Depression symptoms and externalizing behavior problems were assessed with the DSM-oriented affective problem scale (14 items, α range: = .83 – .86), and the externalizing problem scale (33 items, α range: = .90 – .91) from Adult Self Report form of the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASR ASEBA; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2003). Substance use items were removed from the externalizing scale to eliminate item overlap with our outcomes of interest. We used the standard ASR response options: 0=not true, 1=somewhat or sometimes true, and 2=very true or often true. Social anxiety (19 items, α range: = .93 – .94) was assessed using the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS, Mattick & Clarke, 1998). Participants were asked to rate how characteristic each item was for them using the follow response options: 1=not at all, 2=slightly, 3=moderately, 4=very, 5=extremely. For all ASR and SIAS scales, an average item score was computed.

Analysis Plan

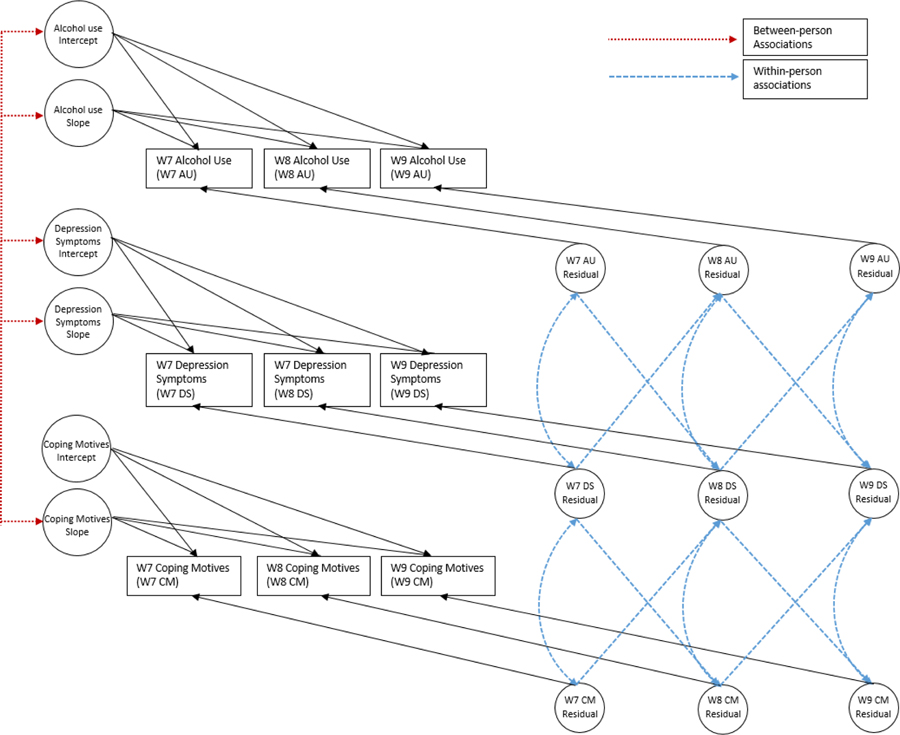

Our hypotheses were tested using Latent Curve Model with Structured Residuals (LCM-SR, Curran et al., 2014) estimated in Mplus version 8.0 using Maximum Likelihood Robust Estimation (MLR, Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2017). We modeled the data by wave rather than age because it was not feasible to model individually varying times of observation with continuous age given the demands of numerical integration, and structuring the data by age cohorts led to sparseness of some elements of the observed covariance matrix. Part of a multivariate LCM-SR is presented in Figure 1, which shows relevant paths and covariances for alcohol use, depression symptoms, and alcohol coping motives. The full model included alcohol problems, social/enhancement motives, age, and gender, however, we excluded these variables to simplify this conceptual figure. As shown in Figure 1, these models included covariances among growth factors (between-person associations), and cross-lag paths between residuals and within-time residual covariances (within-person or time-specific associations). Separate models were run for alcohol and cannabis, and for each domain of internalizing symptoms (depression and social anxiety symptoms) resulting in four multivariate LCM-SR models. Our model testing procedure followed that of Curran et al. (2014) and began by estimating univariate growth models, and then adding autoregressive paths between residuals and testing equality of the residual variances and autoregressive paths within construct using a nested model χ2 test. After establishing the best fitting univariate models, they were combined into the multivariate LCM-SR.

Figure 1.

Conceptual figure of part of a latent curve model with structured residuals (LCM-SR) for alcohol use, depressive symptoms, and coping motives

We tested whether gender moderated estimates in our LCM-SR models using a multiple group approach as some findings suggest gender differences in coping motived substance use (Cooper et al., 2016; Kuntsche et al., 2005). Nested tests suggested group differences on the depression growth factor intercepts, and the alcohol and cannabis use growth factor intercepts. Females were higher in depression and males were higher in alcohol and cannabis use. Given the general lack of gender differences, we report results below for the overall sample, and included gender (age) as statistical control variables predicting the latent intercepts and slopes.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables can be found in supplemental Tables S1 and S2. The sample typical consumed 1–2 drinks per drinking day across assessments with a range of 1–15 drinks. Typical number of drinking days per week was 1–2 across assessments with a range of 1–7. Drinkers typically experienced 6–7 alcohol-related problems in the past year with a range of 0–45. On average, drinkers reported drinking for social/enhancement reasons about half the time, and reported coping drinking some of the time. Frequency of cannabis use started out low at Wave 1 (average of 8 times in the past year) and increased to 84 and 102 times at Waves 2 and 3. A small percent of participants reported daily cannabis use (6–10% across the assessments). Typical number of cannabis-related consequences was between 6–7 across the three assessments with a range of 0–50. Similar to alcohol use, cannabis users reported using for social/enhancement reasons about half the time, and reported coping use some of the time. Mental health symptoms and motives variables showed moderate to high one-year stabilities (rs = .55 – .84), and coping motives were moderately associated with depression and social anxiety symptoms at each assessment.

Univariate Models

We were limited to evaluating linear growth because we had three repeated measures. Slope factor loadings (0, 1, and 2) were set so that the intercept represented Wave 7 levels of the variable. Determining the best fitting growth model involved comparing several models for each variable with and without random effects and with and without a linear slope. We do not report all of the nested tests here for the sake of brevity, but provide fit information for the final models (model χ2, comparative fit index, CFI, and root mean squared error of approximation, RMSEA).

The growth model for alcohol use included a random intercept and slope without autoregressive paths between residuals and no equality constraint for the residual variances (χ2 (1 df) = .081, p = 0.78, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA<0.01). The mean of the slope factor was not statistically significant suggesting that on average there was no change in drinks per drinking day, but there was significant individual variability in rate of change. The growth model for cannabis suggested increases in frequency and significant variability in both the intercept and slope, and the model included equality constraints for the residual variances across time but did not include autoregressive paths (χ2 (3 df) = 2.07, p = 0.56, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA<0.01). Growth modeling of the alcohol and cannabis problems supported linear increases with a random effect for the intercept but not slope. Nested tests supported constraining residual variances to be equal for both models and adding equal autoregressive paths for alcohol problems, but not for cannabis problems. These autoregressive paths suggests some carryover effects of alcohol problems across adjacent years above and beyond growth. The final models fit the data well (χ2 (4 df) = 9.39, p < 0.06, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.07 for alcohol problems, and χ2 (5 df) = 8.16, p < .15, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = .05 for the cannabis problems).

Growth models varied for motives. The best fitting model for alcohol coping and social/enhancement motives was an random intercept only model with residual variances constrained to be equal and equal autoregressive paths between residuals (χ2 (5 df) = 4.90, p < .43, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < .01 for alcohol coping motives and χ2 (5 df) = 3.969), p < .55, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < .01 for alcohol social/enhancement motives). The growth model for cannabis coping motives included a random intercept and slope (suggesting increases), and residual variances and autoregressive paths constrained to equal over time ((χ2 (4 df) = 1.78, p = 0.78, CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = 0.01). The final model for cannabis social/enhancement motives included a random intercept only model with residual variances constrained to be equal and no autoregressive paths (χ2 (6 df) = 8.21, p = 0.23, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.04).

Growth models varied slightly for the three domains of mental health symptoms. The best fitting model for externalizing behavior and social anxiety was an random intercept only model with equal residual variances and equal autoregressive paths (χ2 (5 df) = 3.040, p < .69, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < .01 for externalizing behavior, and χ2 (5 df) = 5.110, p < 0.40, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < 0.01 for social anxiety). Here again these autogressive paths suggest some carry over effects of symptoms between adjacent years above and beyond growth. The model for depression included linear increases with a random intercept and slope, equal residual variances without autoregressive paths (χ2 (3 df) = 2.306, p = 0.51, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < .01).

Multivariate Models

We next combined the univariate LCM-SR models into multivariate models. It was not feasible to combine all of the univariate models into one model. Accordingly, separate multivariate models were run for each substance (alcohol and cannabis) and for each domain of internalizing symptoms (depression and social anxiety symptoms) for a total of four multivariate models. In these models, growth factor covariances represent between-person associations. Covariances among structured residuals within time represent contemporaneous within-person associations. Nested model tests were used to evaluate the residual covariances for equivalence across time. Our models also included cross-lag paths among structured residuals (Wave 7 predicting Wave 8 and Wave 8 predicting Wave 9) when indicated by nested model tests. The cross-lag paths represent within person prospective associations. The equivalence of these paths across the two lags and their equality were evaluated using a nested model test. We do not report the nested tests for sake of brevity and the details of each model and constraints supported with final model fit indices are reported in Supplemental Table S3.

Alcohol Use and Depression.

Growth factor correlations (between-person associations) are presented in Table 1. The depression symptoms intercept was positively correlated with coping, but not social/enhancement motives. High levels of depression symptoms at Wave 7 were associated with high levels of coping drinking. Depression symptoms were not associated with the alcohol use intercept or slope. However, high levels of depression symptoms at Wave 7 were associated with high levels of Wave 7 alcohol problems. This supports the idea that depression is associated specifically with use for coping motives and alcohol-related problems, but not general alcohol use. Both coping and social/enhancement reasons for drinking at Wave 7 were associated levels of drinking and problems at Wave 7. Declines in alcohol use quantity were associated with coping motives at Wave 7. This may be attributable to coping motives being associated with higher levels of alcohol use (intercept correlations) and hence there is more opportunity for alcohol use to decline among frequent coping drinkers.

Table 1.

Growth Factor Covariances (Standardized) for Multivariate Latent Curve Models with Structured Residuals

| Alcohol: Depression | Coping | Soc/Enh | Int Dep | Slope Dep | Extern | Int Alc Q | Slope Alc Q | Alc Prob |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coping | 1 | |||||||

| Soc/Enh | .52* | 1 | ||||||

| Int Depression | .47* | .16 | 1 | |||||

| Slope Depression | .04 | .08 | −.09 | 1 | ||||

| Extern | .48* | .30* | .56* | .04 | 1 | |||

| int Alc Quant | .38* | .48* | .16 | .04 | .38* | 1 | ||

| slope Alc Quant | −.26* | −.21 | −.25 | .21 | −.33* | −.68* | 1 | |

| Alc Prob | .49* | .56* | .37* | .01 | .71* | .71* | −.46* | 1 |

| Alcohol: Soc Anx | Coping | Soc/Enh. | Soc Anx | Extern | Int QxF | Slope QxF | Alc Prob | |

| Coping | 1 | |||||||

| Soc/Enh | .47* | 1 | ||||||

| Soc Anx | .51* | .11 | 1 | |||||

| External | .56* | .32* | .33* | 1 | ||||

| Int Alc Quant | .32* | .46* | −.01 | .36* | 1 | |||

| Slope Alc Quant | −.26* | −.20 | −.03 | −.37* | −.73* | 1 | ||

| Alc Prob | .47* | .58* | .11 | .69* | .71* | −.50* | 1 | |

| Cannabis: Depression | Coping | Soc/Enh | Int Dep | Slope Dep | Extern | Int Freq | Slope Freq | Can Prob |

| Coping | 1 | |||||||

| Soc/Enh | .65* | 1 | ||||||

| Int Depression | .31* | .01 | 1 | |||||

| Slope Depression | −.06 | .09 | −.28 | 1 | ||||

| External | .42* | .03 | .62* | −.05 | 1 | |||

| Int Can Freq | .44* | .23* | −.08 | .39 | .32* | 1 | ||

| Slope Can Freq | .04 | .26* | .05 | −.54 | −.10 | −.53* | 1 | |

| Can Prob | .75* | .33* | .45* | −.18 | .59* | .55* | −.05 | 1 |

| Cannabis: Soc Anx | Coping | Soc/Enh | Soc Anx | Extern | Int Freq | Slope Freq | Can Prob | |

| Copipng | 1 | |||||||

| Soc/Enh | .66* | 1 | ||||||

| soc anx | .31* | .12 | 1 | |||||

| External | .49* | .29* | .38* | 1 | ||||

| Int Can Freq | .38* | .27* | −.07 | .33* | 1 | |||

| Slope Can Freq | .19 | .24* | −.06 | .01 | −.52* | 1 | ||

| Can Prob | .72* | .50* | .37* | .54* | .55* | −.01 | 1 | |

Note. Coping = Coping Motives; Soc/Enh = Social and Enhancement Motives; Int = Intercept; Extern = Externalizing; Soc Anx = Social Anxiety; Alc Quant = Alcohol Quantity; Can Freq = Cannabis Frequency; Alc Prob = Alcohol Problem; Can Prob = Cannabis Problem.

The residual correlations represent within-person (or time-specific) cross-sectional associations and they are presented in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, depression symptoms were positively associated with all variables other than alcohol use and alcohol problems. The residuals represent deviations from a person’s expected value of that variable, and so for example, the positive association between depression and coping motives suggests that when a person experiences more than their expected level of depression symptoms given growth, he/she is likely to engage in coping drinking. This was also true with respect to social/enhancement motives, although this correlation was less than half the magnitude of the correlation with coping motives. Also notable is that when a person engaged in coping drinking more than expected given his/her stable propensity for coping drinking, he/she did not necessarily drink at higher levels, but they did experience more alcohol-related problems. A limitation of these residual correlations is that they are cross-sectional representing associations within a given year, and are not helpful for establishing temporal precedence. Temporal precedence can be inferred from the cross-lag paths between structured residuals, which are described next.

Table 2.

Residual Covariances (Standardized) from Multivariate Latent Curve Models with Structured Residuals

| Alcohol: Depression | Coping | Soc/Enh | Depression | Extern | Alc Quant | Alc Prob |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coping | 1 | |||||

| Soc/Enh | .33* | 1 | ||||

| Depression | .43* | .16* | 1 | |||

| Extern | .30* | .29* | .67* | 1 | ||

| Alc Quant | .02 | .18* | −.15 | −.01 | 1 | |

| Alc Prob | .29* | .28* | .09 | .21* | .25* | 1 |

| Alcohol: Soc Anx | Coping | Soc/Enh | Soc Anx | Extern | Alc Quant | Alc Prob |

| Coping | 1 | |||||

| Soc/Enh | .36* | 1 | ||||

| Soc Anx | .44* | .21* | 1 | |||

| Extern | .25* | .26* | .25* | 1 | ||

| Alc Quant | .09 | .18* | −.08 | .01 | 1 | |

| Alc Prob | .31* | .27* | .10 | .21* | .25* | 1 |

| Cannabis: Depression | Coping | Soc/Enh | Depression | Extern | Can Freq | Can Prob |

| Coping | 1 | |||||

| Soc/Enh | .54* | 1 | ||||

| Depression | .37* | .13 | 1 | |||

| Extern | .24* | .28* | .61* | 1 | ||

| Can Freq | .40* | .33* | .53* | .17* | 1 | |

| Can Prob | .39* | .36* | .34* | .38* | .33* | 1 |

| Cannabis: Soc Anx | Coping | Soc/Enh | Soc Anx | Extern | Can Freq | Can Prob |

| Coping | 1 | |||||

| Soc/Enh | .54* | 1 | ||||

| Soc Anx | .27* | −.02 | 1 | |||

| Extern | .25* | .17 | .23* | 1 | ||

| Can Freq | .43* | .37* | .33* | .20 | 1 | |

| Can Prob | .41* | .26* | .07 | .34* | .36* | 1 |

Note. Coping = Coping Motives; Soc/Enh = Social and Enhancement Motives; Extern = Externalizing; Alc quant = Alcohol Quantity; Alc Prob = alcohol problems Can Freq = Cannabis Frequency; Can Prob = Cannabis Problem

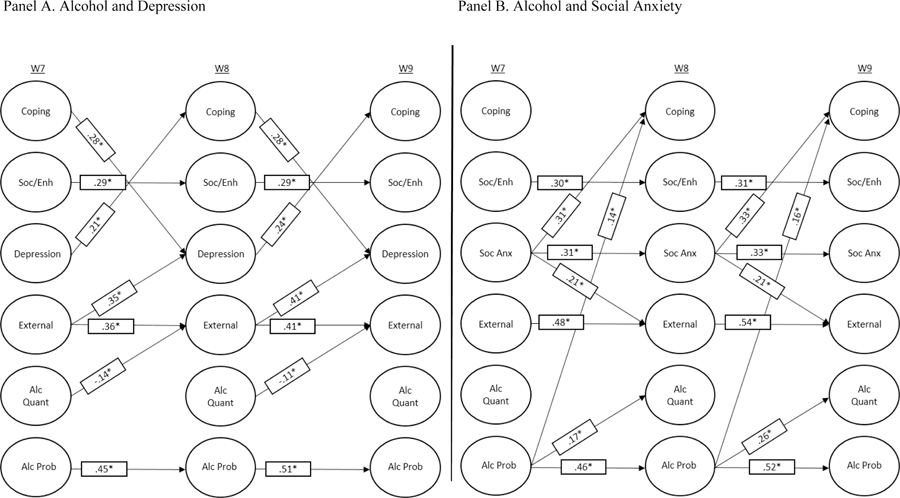

Statistically significant cross-lag paths are shown in Panel A of Figure 2 (path coefficients with 95% confidence intervals are presented Supplemental Table 4). As shown in Figure 2, depression symptoms and coping motives were reciprocally related. The experience of elevated depression symptoms relative to person’s expected level of symptoms given growth was associated with increased frequency of coping motivated drinking one year later, and more frequent coping drinking relative to a person’s stable propensity to drink for coping reasons was associated with increased depression symptoms one year later. The standardized coefficients can be interpreted to suggest that with a standard deviation increase in depression symptoms there is a .21–.24 standard deviation increase in coping drinking on year later, and with a standard deviation increase in coping drinking, there is a .28 increase in depression symptoms on year later. Within-person prospective associations in Panel A of Figure 2 showed very few associations with alcohol use or problems.

Figure 2.

Residual Cross-Lags from Alcohol Models

In sum, at the within-person level we found support for reciprocal associations between coping drinking and depression symptoms. However, we found no evidence that coping drinking and depression were prospectively associated with alcohol-related problems, but there was cross-sectional support for associations between coping drinking and alcohol-related problems at both the between- and within-person level. Furthermore, consistent across both between- and within-person levels of analysis, cross-sectional correlations suggested that depression symptoms were more strongly associated with coping motives than with social/enhancement motivates.

Alcohol and Social Anxiety.

The pattern of between-person growth factor correlations for social anxiety was similar findings for depression symptoms (see Table 1). One difference was that unlike depression symptoms, there was no association between social anxiety and alcohol problems at Wave 7 (social anxiety and alcohol problems intercept correlation). The within-person (or time-specific) correlations among structured residuals are presented in Table 2, and correlations were similar those observed for depression symptoms. The positive association between social anxiety and coping motives suggests that when a person experienced more social anxiety symptoms than expected given their stable propensity to experience symptoms, this was associated with high levels of coping drinking. This was also true with respect to social/enhancement motives, although this correlation was less than half the magnitude of the correlation with coping motives. When an individual engaged in more coping drinking than expected given his/her stable propensity for coping drinking, he/she did not necessarily drink at higher levels, but did experience more alcohol-related problems.

Statistically significant cross-lag paths are shown in Panel B of Figure 2 (path coefficients and 95% confidence intervals are presented in Supplemental Table 4). Social anxiety prospectively predicted coping motives such that the experience of elevated social anxiety symptoms relative to a person’s stable propensity to experience symptoms was associated with increased frequency of coping drinking one year later. The coefficients suggests that a one standard deviation increase in social anxiety symptoms in a given year was associated with a .31 to .33 standard deviation increase in coping drinking one year later. However, unlike depression symptoms, coping motives did not prospectively predict social anxiety. Alcohol problems were prospectively associated with quantity of alcohol use one year later and with increased coping drinking. These effects were not supported in the depression model, and likely emerged in this model because of less overlap between social anxiety and externalizing symptoms than between depression and externalizing symptoms.

In sum, findings for social anxiety differed somewhat from those for depression. There was no support prospective reciprocal within-person associations between coping drinking and social anxiety. Although social anxiety prospectively predicted increases in coping drinking (like depression), coping drinking did not, in turn, lead to exacerbation of social anxiety symptoms. Also notable is that social anxiety was not associated with alcohol-related problems at either the between- or within-person levels. Like depression, social anxiety was more strongly correlated cross-sectionally with coping than with social/enhancement motives at both the between-and within-person level.

Cannabis Use and Depression Symptoms.

Between-person growth factor correlations were similar to those observed for alcohol and depression symptoms (see Table 1). The depression symptoms intercept was positively correlated with the cannabis coping motives intercept, but not enhancement/social motives intercept. High levels of depression symptoms at Wave 7 were associated with cannabis coping motives at W7. Depression Symptom growth factors were not associated with cannabis use growth factors. However, high levels of depression symptoms at Wave 7 were associated with high levels of Wave 7 cannabis-related problems. Both coping and enhancement/social motives at Wave 7 were associated with the frequency of cannabis use and problems at Wave 7. However, coping motivates were more strongly correlated with problems (large versus moderate sized effect).

Within-person (or time-specific) correlations among the structured residuals in Table 2 suggest that depression symptoms were positively associated with all variables other than social/enhancement motives. The positive association between depression symptoms and coping motives suggests that when a person experienced more than their expected level of depression symptoms given growth, he/she was likely to engage in cannabis use for coping reasons in a given year. Further, the positive correlation between depression symptoms and cannabis use and problems suggest that when an adolescent experienced more than their expected level of depression symptoms given growth, he/she was likely to use cannabis more frequently and experience more cannabis-related problems. Also notable is that higher coping or social/enhancement motives than expected given a person’s stable propensity to use for these reasons, was associated with more frequent cannabis use and more cannabis-related problems. As noted above, these within-person residual correlations provide limited insight into temporal precedence because they are cross-sectional and represent associations within a given year.

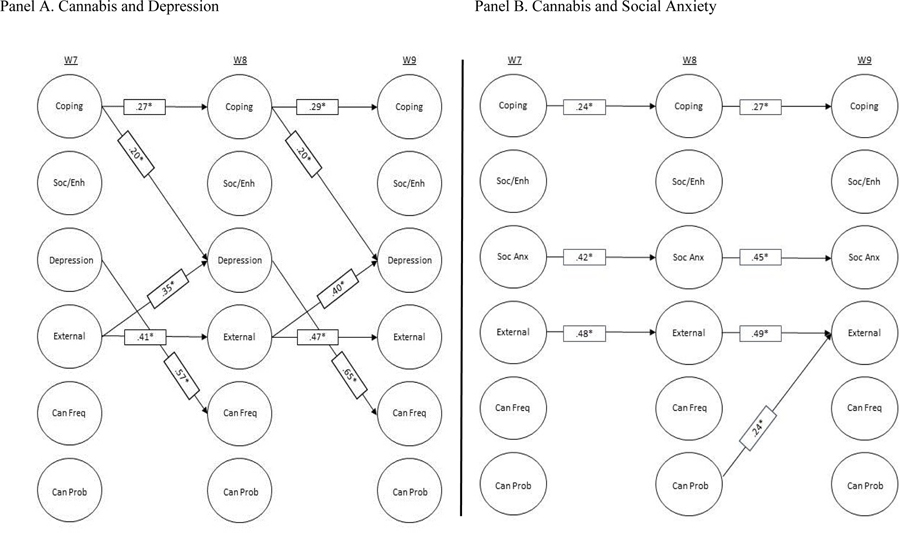

Statistically significant cross-lag paths are shown in Panel A of Figure 3. Cannabis coping motives were prospectively associated with depression such that higher cannabis coping motives than expected given a person’s stable propensity to use for coping reasons was associated with increased depression symptoms one year later. A one standard deviation increase in coping motives was associated with a .21 increase in depression symptoms. Although depression symptoms were not prospectively associated with coping motives, adolescents who experience elevated depression symptoms relative to their expected level of symptoms given growth increased their frequency of cannabis use one year later. A one standard deviation increase in depression symptoms was associated with a .57–.65 standard deviation increase in cannabis use. None of the variables in the model prospectively predicted cannabis problems.

Figure 3.

Residual Cross-lagged Paths for Marijuana Models

In sum, we found little evidence for reciprocal within-person prospective associations between depression and cannabis coping motives. Although cannabis coping motives prospectively predicted exacerbation of depression symptoms, depression symptoms did not predict subsequent coping motivates. Consistent with findings from the alcohol use model, depression symptoms were more strongly cross-sectionally associated with cannabis coping motivates than with social/enhancement motives at the between-person level. Cross-sectional associations suggested that cannabis coping motives were associated with use-related problems at both the between- and within-person levels, and also associated with more frequent use in general.

Cannabis Use and Social Anxiety.

Between-person growth factor correlations suggest associations similar to those observed for cannabis use and depression symptoms (see Table 1). Social anxiety was associated with coping motives, but not social/enhancement motives, and with cannabis-related problems, but not cannabis use. Both coping and social/enhancement motives were associated with use and problems.

Within-person (or time-specific) correlations among structured residuals suggest that social anxiety was associated with cannabis use, but not problems (see Table 2). Adolescents who experienced elevated social anxiety symptoms in a given year relative to his/her stable propensity to experience such symptoms used cannabis more frequently than was expected given growth. Like depression symptoms, social anxiety was associated with coping motivates, but not with social/enhancement motives. Exacerbation of social anxiety symptoms in a given year above one’s stable propensity to experience symptoms was associated with frequent coping use.

Statistically significant cross-lag paths are shown in Panel B of Figure 3 (path coefficients with 95% confidence intervals are presented in Supplemental Table 4). As shown in Figure 3, there was no evidence for a prospective association between social anxiety symptoms and coping motives, and this was contrary to depression where we found prospective association between coping motives and depression. In fact, very few cross-lagged associations were evident.

In sum, findings regarding cannabis and social anxiety were similar to those for cannabis and depression. One exception as that we found no prospective association between coping motivates and social anxiety symptoms.

Discussion

Though self-medication and coping theories are commonly invoked to account for adolescent and young adult substance use, empirical evidence has been mixed, and relatively few studies evaluated reciprocal associations implied by these theories. In the current study, we sought to test self-medication pathways pertaining to two of the most commonly used substances among adolescents, alcohol and cannabis. Important contributions of this work included: (1) testing bidirectional associations; (2) distinguishing within-person and between-person associations in the context of developmental trajectories of use in order to understand both stable and dynamic components of substance use coping motives; and (3) considering social anxiety and depression symptoms, two domains of emotional distress commonly considered within a self-medication framework. In addition, we statistically controlled for a potential confound (externalizing symptoms) and examined use and use-related problems because some evidence suggests that coping motives may be more germane to use-related problems (Cooper et al., 2016; Kuntsche et al., 2005). Results suggested a complex pattern of associations that offered some support for a self-medication pathway.

Findings were most consistent with respect to alcohol use, such that both depression and social anxiety symptoms were associated with drinking for coping reasons at both the between and within person levels, and importantly, high levels of both depression and social anxiety symptoms were prospectively associated with increases in coping drinking. Moreover, coping drinking was associated with increases in subsequent depression symptoms, suggestive of a reciprocal process that moves youth toward greater and greater reliance on alcohol as a coping strategy. Findings were less consistent for cannabis use. Although using cannabis for coping reasons was associated with subsequent exacerbation of depressive symptoms, we did not find evidence for reciprocal associations. Cross-sectional associations at both the between and within person level suggested that cannabis coping motivates were associated with high levels of cannabis-related problems. We discuss both between- and with-in person associations in more detail below.

Between-Person Associations

Between-person associations in our analysis are based on an individual’s standing on a distribution of scores relative to others in the sample and represent trait-like associations. These associations provided some support for a self-medication pathway with respect to both alcohol and cannabis use. Individuals experiencing high stable levels of emotional distress (either depression or social anxiety) across the three annual assessments tended to drink or use cannabis for coping reasons more than individuals low in emotional distress. Emotional distress was more weakly associated with social/enhancement use motives at the between person level (correlations were ½ the size of those with coping motives), suggesting some specificity of association with coping motives. Moreover, frequent coping drinking was associated with high levels of use and use-related problems.

There is evidence in the literature suggesting that, when internalizing symptoms marked by dysphoria or negative affect are linked to alcohol outcomes, it is often alcohol problems, rather than alcohol use (Kuntsche et al., 2005; Martens et al., 2008; Merrill & Read, 2010; Merrill, Wardell, & Read, 2014; Read, Radomski, & Wardell, 2017; Willem, Bijttebier, Claes, & Uytterhaegen, 2012). Our findings are consistent with this as the general pattern of between-person associations suggested that individuals experiencing high levels of depression symptoms also experienced high levels of use-related problems. Furthermore, associations of coping drinking with use-related problems were much stronger (twice as large) than associations between coping motives and use.

As hypothesized, the between-person associations suggested stronger support for a self-medication pathway for coping motivated use compared to general use, and this may in part account for inconsistent findings in the literature as not all studies testing this risk pathway include coping motives (e.g., Mason, Hitchings, & Spoth, 2008; Marmorstein, Iacono, & Malone, 2010). This is perhaps not surprising as youth report a variety of motives for substance use (Cooper et al., 2016), and hence just examining general use may obscure associations relevant to the self-medication pathway. Interpretation of our between-person associations is limited by their cross-sectional nature, especially given evidence for bi-directional associations among many of these variables (e.g., Parrish et al., 2016; Brook, D. Brook, Zhang, Cohen, & Whiteman, 2002; Hallfors, Waller, Bauer, Ford, & Halpern, 2005).

Within-Person Associations

An important methodological feature of our study is that we disaggregated between- and within-person associations, allowing for a clearer understanding of how a self-medication risk pathway may operate at multiple levels. Theory posits motivations for substance use have a stable trait like component that varies between individuals, as well as a more dynamic component that varies within a person in response to changing developmental and contextual demands (Cooper et al.1995; Cooper et al., 2008; Cox & Klinger, 2011). Although prior work has examined coping motivated use within-person associations (e.g., Arbeau et al., 2011; Armeli, O’Hara, Ehrenberg, Sullivan, & Tennen, 2014; Armeli, et al., 2015; Littlefield et al., 2012), these studies utilized burst designs typically examining daily fluctuations in internalizing symptoms and coping motivated use. Adolescence is a time when substance use escalates with significant heterogeneity and late adolescence is period when youth approach peak levels of problem use (Brown et al, 2008). Short-term intensive burst designs do not provide insight about the long-term developmental sequela of coping motivated use. Our study extends this work by examining between- and within-person associations across the span of three years in late adolescence.

Our findings support the idea that coping motives for alcohol and cannabis have both a stable trait-like component as well as a more dynamic component that fluctuates year-to-year. This was also true of depression and social anxiety symptoms. Adolescence is a period of significant social transitions as well as physical and psychological changes that can be stressful (Spear, 2000) and often accompanied by intense emotional experiences (Larson et al., 2002; Petersen et al., 1993). It is therefore not surprising that we observed significant within-person variation in emotional distress and substance use coping motivates across our assessments. Furthermore, cross-sectional within-person associations suggested that when a person experienced higher than his/her stable propensity for emotional distress (depression and social anxiety symptoms), this was accompanied by stronger alcohol and cannabis coping motives. Like our between-person associations, there was some evidence of specificity in that elevations in depression and social anxiety symptoms were more strongly associated with coping motivates (moderate sized correlations) compared to social/enhancement motives (small sized correlations). Also similar to the between-person associations, coping drinking was more strongly associated with alcohol problems (moderate correlations) than use (small correlations).

Cannabis coping motives showed less specificity with respect to problems at the within-person level. When an individual’s cannabis coping motives were higher than his/her stable propensity to engage in coping use in a given year, this was similarly associated with use and problems (modest sized correlations). These findings are consistent with prior work suggesting that coping drinking is more strong linked to problems (Kuntsche et al., 2005; Martens et al., 2008; Merrill & Read, 2010; Merrill et al., 2014; Read et al., 2017; Willem et al., 2012), but that cannabis use to cope is more broadly associated with use and problems (e.g., Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2007; Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005; Lee et al., 2007). The specific reasons for this difference across alcohol and cannabis use are unclear. One possible explanation is the different behavioral effects of each drug. For example, alcohol, but not cannabis use, can lead to acute increases aggression (De Sousa Fernandes Perna, Theunissen, Kuypers, Toennes, & Ramaekers, 2016), and hence, stronger links to negative consequences.

Our cross-lagged within-person associations provide the strongest evidence for a self-medication pathway as they help establish temporal precedence and suggest that when a person experiences an increase in emotional distress during a given year, this is predictive of later coping use. For both depression and social anxiety, elevations in emotional distress were associated with subsequent increases in coping drinking. This is compatible with self-medication models. However, coping drinking was not predictive of alcohol problems. This was surprising given that the literature suggests stronger links between coping motives and problems. One possibility is that alcohol problems may be more trait like than use, and hence vary less from one assessment to the next after one accounts for between-person variance. Indeed, we found lower variance estimates at the within-person level for alcohol problems (standardized residuals = .68 to .73) compared to alcohol use (.85 to .90).

The self-medication pathway operated differently at the within-person level for cannabis use. Elevations in cannabis coping motivates in a given year relative to a person’s stable propensity for coping use was prospectively associated with increases in depression symptoms, which in turn, were associated with increases cannabis use. Why depression did not predict cannabis coping motivates is unclear, and warrants replication and further exploration in future studies. One possibility is that we had fewer cannabis users than alcohol users, and so our cannabis models may have had less power to detect effects. We also did not find any evidence for a self-medication pathway for cannabis use with respect to social anxiety. That is, elevations in social anxiety were not associated with coping motives, or with cannabis use or problems. Although some prior research has found that social anxiety is associated with cannabis use and problems and with coping motivates (e.g., Buckner, Crosby, Wonderlich, & Schmidt, 2012; Buckner, Zvolensky, & Schmidt, 2012), these studies examined between person associations. Our findings also provided support for between-person associations. It is possible that social anxiety represents a trait-like vulnerability for self-medication motivated cannabis use that doesn’t operate at the within person level. Here again the relatively small sample of cannabis users may have limited our power to detect effects.

We also found that elevations in alcohol coping motives in a given year relative to a person’s stable propensity for coping drinking were associated with increases in subsequent depression symptoms. This is compatible with an emerging literature suggesting the drinking to cope with emotional distress paradoxically increases depressive symptoms (Armeli et al., 2014; 2015). There is robust evidence that depression is an outcome of drinking, but no studies to our knowledge have examined whether coping drinking in particular (rather than drinking more generally) may contribute to such outcomes using a long-term longitudinal design. These data suggest that coping drinking is part of a paradoxical process, whereby an individual seeks out emotional relief from depressive symptoms through drinking, which in turn, is associated with more rather than less depression. Such a process is specific to depression as coping drinking did not predict subsequent social anxiety. This again highlights the importance of disaggregating emotional distress into specific types of distress, in order to isolate processes that are unique to specific domains of emotion as has been suggested by several authors (Colder et al., 2010; Hussong et al., 2017).

Limitations and Conclusions

Results from this study should be understood within the context certain limitations. First, although our community sample provided an opportunity to examine the emergence of substance use coping motivates within a normative developmental context, findings may not generalize to high risk or clinical samples. Second, we focused on social anxiety and depression as these clusters of internalizing symptoms have been strongly implicated in coping motivated substance use. Other domains of internalizing symptoms may or may not operate in a similar fashion (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety), and this would be a useful direction for future research. Third, although a strength of our study was the longitudinal design, our annual assessments may have missed some of the dynamic interplay between internalizing symptoms, motives, and substance use outcomes. It would be useful to replicate our findings utilizing multiple burst periods of assessment that are spread over multiple years as this would allow one to examine how daily processes may change over the course of years as adolescents escalate in their use. Fourth, our models were complex and the small sample size may have limited power to detect effects. This seems most applicable to our cannabis models. Finally, individual differences in addition to internalizing symptoms are likely to influence alcohol and cannabis coping motivates, but we were reluctant to include more variables in our already complex models. Personality is strong candidate for inclusion as prior work has shown strong links between personality and coping motives (e.g., Littlefield et al., 2010) and this would be useful direction for future work.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides evidence at both the between- and within-person for self-medication models in adolescence. The most compelling evidence suggests that coping drinking is part of a paradoxical reciprocal process, whereby an individual seeks out emotional relief from distress through drinking, which in turn, is associated with more rather than less distress. This process was evident at the within- person level suggesting time specific elevation in an individual’s emotional distress can trigger such a process as most self-medication theories would predict. Cross-sectional associations hinted at a similar pattern for cannabis use, but did not replicate in the prospective associations, perhaps because of our smaller sample of cannabis users or because coping motivations operate different for cannabis. There were also differences in how social anxiety and depression were related to coping motives and use. In general, cross-sectional associations were similar for social anxiety and depression symptoms, but we saw little evidence of prospective effects of social anxiety. This suggests that social anxiety may operate more acutely on coping motives and use, and it is important to disaggregate internalizing symptom clusters.

In terms of intervention implications, our findings suggest that both between- and within-person level variability can be useful for identifying targets for intervention. Among youth who are emotionally distressed, it would be useful to target motives for use – coping motives in particular, and promote alternative coping strategies. Identifying those who are chronically motivated to use substances as a way of coping with emotional distress (between-person differences) or those experiencing acute elevations in coping motivates (within-person differences), and connecting them with coping skills interventions may be especially beneficial for those in this high-risk group (e.g., Conrod, Castellanos-Ryan, & Strang, 2010; Litt, Kadden, Kobela-Cormier, & Petry, 2008). Further, feedback-based interventions such a norms-based or motivational interventions (e.g., Blevins, Walker, Stephens, Banes, & Roffman, 2018; Labrie et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2011) could be tailored to provide personalized information about specific motivations for use. For those with strong coping motivations, it might be useful for interventionists to highlight that, though coping motivated use may relieve distress acutely, in the long run, it leads to increasingly higher levels of distress, at least with respect to alcohol. Also, findings from our within-person analysis suggest that a fruitful application of these findings may be in “just in time adaptive interventions” that deliver feedback via text message in a manner that is individualized to a person’s own report of mood states (Muench, van Stolk-Cooke, Morgenstern, Kuerbis, & Markle, 2014; Suffoletto, 2016). Accordingly, such interventions could catch adolescents and young adults in moments of distress and accompanying increases in coping motivations, providing feedback and alternative coping strategies that could be effectively employed during periods of greatest risk as they occur.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA019631) awarded to Dr. Craig R. Colder.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla L (2003). Manual for the ASEBA adult forms & profiles: for ages 18–59: Adult self-report and adult behavior checklist. ASEBA. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeau KJ, Kuiken D, & Wild TC (2011). Drinking to enhance and cope: A daily process study of motive specificity. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 1174–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Conner TS, Covault J, Tennen H, & Kranzler HR (2008). A serotonin transporter gene polymorphism (5-HTTLPR), drinking-to-cope motivation, and negative life events among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69, 814–823. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S Covault J, & Tennen H (2018). Long-term changes in the effects of episodic-specific drinking to cope motivation on daily well-being. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32, 715–726. doi:10.1037.adb0000409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Dranoff E, Tennen H, Austad CS, Fallahi CR, Raskin S, … & Pearlson G (2014). A longitudinal study of the effects of coping motives, negative affect and drinking level on drinking problems among college students. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 27(5), 527–541. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2014.895821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, O’Hara RE, Ehrenberg E, Sullivan TP, & Tennen H (2014). Episode-specific drinking-to-cope motivation, daily mood, and fatigue-related symptoms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75, 766–774. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Sullivan TP, & Tennen H (2015). Drinking to cope motivation as a prospective predictor of negative affect. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(4), 578–584. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer PE, Garmezy LB, McLaughlin RJ, Pokorny AD, & Wernick MJ (1987). Stress, coping, family conflict, and adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 10, 449–466. doi: 10.1007/BF008466144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CE, Banes KE, Stephens RS, Walker DD, & Roffman RA (2016). Motives for marijuana use among heavy-using high school students: An analysis of structure and utility of the comprehensive marijuana motives questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors, 57, 42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CE, Walker DD, Stephens RS, Banes KE, & Roffman RA (2018). Changing social norms: The impact of normative feedback included in motivational enhancement therapy on cannabis outcomes among heavy-using adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, & Bernstein A (2007). Marijuana use motives: Concurrent relations to frequency of past 30-day use and anxiety sensitivity among young adult marijuana smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 32(1), 49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Cohen P, & Whiteman M (2002). Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(11), 1039–1044. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, & Warren MP (1989). Biological and social contributions to negative affect in young adolescent girls. Child Development, 60, 40–55. doi: 10.2307/1131069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, McGue M, Maggs J, Schulenberg J, Hingson R, Swartzwelder S, … Murphy S (2008). A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics, 121 Suppl 4, S290–310. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, & Schmidt NB (2012). Social anxiety and cannabis use: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(2), 297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Heimberg RG, Eckerd AH, & Vinci C (2012). A biopsychosocial model of social anxiety and substance use. Depression and Anxiety, 30, 276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, & Schmidt NB (2012). Cannabis-related impairment and social anxiety: The roles of gender and cannabis use motives. Addictive Behaviors, 37(11), 1294–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Chassin L, Lee MR, & Villalta IK (2010). Developmental perspectives: Affect and adolescent substance use In Kassel JD (Ed.), Substance abuse and emotion (pp. 109–135). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/12067-005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Frndak SE, Lengua LJ, Read JP, Hawk LW Jr., & Wieczorek WF (2018) Internalizing and externalizing problem behavior: A test of a latent variable interaction predicting a two-part growth model of adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(2), 319–330. doi: 10.1007/s10802-017-0277-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, O’Connor RM, Read JP, Eiden RD, Lengua LJ, Hawk LW Jr, & Wieczorek WF (2014). Growth trajectories of alcohol information processing and associations with escalation of drinking in early adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(3), 659–670. doi: 10.1037/a0035271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R, Parks G, & Marlatt G (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE (1987). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 393–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos-Ryan N, & Strang J (2010). Brief, personality-targeted coping skills interventions and survival as a non–drug user over a 2-year period during adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(1), 85–93. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML (1994). Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, & Mudar P (1995). Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 990–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Krull JL, Agocha VB, Flanagan ME, Orcutt HK, Grabe S, … & Jackson M (2008). Motivational pathways to alcohol use and abuse among Black and White adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(3), 485–501. doi: 10.1037/a0012592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Kuntsche E, Levitt A, Barber LL, & Wolf S (2016). Motivation models of substance use: A review of theory and research no motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco In Sher KJ (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders (pp. 375–421). NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, & Klinger EC (2011). A motivational model of alcohol use: Determinants of use and change In Cox WM & Klinger EC (Eds.), Handbook of motivational counseling: Goal-based approaches to assessment and intervention with addiction and other problems (2011 ed., pp. 131–158). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Howard AL, Bainter SA, Lane ST, & McGinley JS (2014). The separation of between-person and within-person components of individual change over time: A latent curve model with structured residuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(5), 879–894. doi: 10.1037/a0035297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson AK, Lundin A, Agardh E, Allebeck P, & Forsell Y (2016). Cannabis use, depression and anxiety: A 3-year prospective population-based study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 193, 103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa Fernandes Perna EB, Theunissen EL, Kuypers KP, Toennes SW, & Ramaekers JG (2016). Subjective aggression during alcohol and cannabis intoxication before and after aggression exposure. Psychopharmacology, 233(18), 3331–40. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4371-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries MW, Dijkman-Caes COM, Delespaul PAEG. (1990). The sampling of experience: A method of measuring the co-occurrence of anxiety and depression in daily life In Maser JD and Cloninger CR (Eds.), Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders (pp. 707–726). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg E, Armeli S, Howland M, & Tennen H (2016). A daily process examination of episode-specific drinking to cope motivation among college students. Addictive Behaviors, 57, 69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer RF, Seeley JR, Kosty DB, Gau JM, Duncan SC, Lynskey MT, & Lewinsohn PM (2015). Internalizing and externalizing psychopathology as predictors of cannabis use disorder onset during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(3), 541–551. doi: 10.1037/adb0000059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fite PJ, Colder CR, & O’Connor RM (2006). Childhood behavior problems and peer selection and socialization: Risk for adolescent alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 1454–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flook L (2011). Gender differences in adolescents’ daily interpersonal events and well-being. Child Development, 82, 454–461. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01521.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröjd S, Ranta K, Kaltiala-Heino R, & Marttunen M (2011). Associations of social phobia and general anxiety with alcohol and drug use in a community sample of adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 46(2), 192–199. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Bauer D, Ford CA, & Halpern CT (2005). Which comes first in adolescence—sex and drugs or depression? American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 29(3), 163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L, & Stawski RS (2009). Persons as contexts: Evaluating between-person and within-person effects in longitudinal analysis. Research in Human Development, 6(2–3), 97–120. doi: 10.1080/15427600902911189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM (2007). Predictors of drinking immediacy following sadness: an application of survival analysis to experiencing sample data. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 226–237. doi: 10.1016.j.addbeh.2006.07.01.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Curran PJ, & Chassin L (1998). Pathways of risk for accelerated heavy alcohol use among adolescent children of alcoholic parents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26(6), 453–466. doi: 10.1023/A:1022699701996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Ennett ST, Cox MJ, & Haroon M (2017). A systematic review of the unique prospective association of negative affect symptoms and adolescent substance use controlling for externalizing symptoms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors : Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 31(2), 137–147. doi: 10.1037/adb0000247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Jones DJ, Stein GL, Baucom DH, & Boeding S (2011). An internalizing pathway to alcohol use disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25, 390–404. doi:10.1037.a0024519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2017). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Jun HJ, Sacco P, Bright CL, & Camlin EA (2015). Relations among internalizing and externalizing symptoms and drinking frequency during adolescence. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(14), 1814–1825. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1058826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Angold A, & Costello EJ (2001). The prospective relation between dimensions of anxiety and the initiation of adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(3), 316–326. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, Molina BS, & Chassin L (2008). A state-trait model of negative life event occurrence in adolescence: Predictors of stability in the occurrence of stressors. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 848–859. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, & Engels R (2005). Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(7), 841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Neighbors C, Zheng C, Kenney SR, … & Grossbard J (2013). RCT of web-based personalized normative feedback for college drinking prevention: Are typical student norms good enough? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 1074–1086. doi: 10.1037/a0034087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]