Short abstract

Objective

We assessed the efficacy of a rational-emotive behaviour therapy psycho-educational programme in reducing depression among chemistry education undergraduates in a Nigerian university.

Methods

Twenty-three chemistry education undergraduates with major depressive disorder were randomised to a treatment group (12) or control group (11). Students were scored using Beck’s Depression Inventory three times (pre-test, post-treatment, and follow-up). An evidence-based protocol for combating depression was used in the treatment. Controls received counselling. Data were evaluated using univariate analysis of variance and two-way mixed analysis of variance.

Results

Mean depression scores did not differ between groups prior to the intervention. Rational-emotive behaviour therapy was effective in reducing depression scores.

Conclusion

Rational-emotive behaviour therapy is an effective tool in assisting university undergraduates (of chemistry education) to manage depression.

Keywords: Depression, undergraduate, chemistry education, Nigeria, rational emotive behaviour therapy, questionnaire

Introduction

Depression is a major challenge for undergraduate university students.1–5 Studies have shown that 25% of students worldwide meet the threshold for major depression at any given time.3 The prevalence of depression has been estimated to range from 1.6% (severe depression) to 58.2% (mild depression) in student populations in Nigeria,4,5 and depression is common among chemistry education undergraduates in Nigerian universities. A 2017 study found that 97.3% of the chemistry education undergraduates in Nigerian universities in the southeastern part of the country experienced high levels of depression; out of 611 chemistry education undergraduates surveyed, 51.1% of women and 48.9% of men reported experiencing moderate to severe depression. Depressive symptoms were recorded for 28.6% of first-year students, 28.6% of second-year students, 35.7% of third-year students, and 7.1% of fourth-year students.6

In Nigeria, the undergraduate chemistry education programme aims to equip individuals with the skills, knowledge, competencies, and intellectual and moral training required for teaching senior secondary school chemistry and engaging in careers in chemistry education, as well as to prepare these individuals for leadership roles in education ministries and public and private educational institutions.7 These objectives can only be achieved when the students are mentally and physically fit to attend lectures, complete course work and related tasks, and study for and pass their examinations. Depression can impair the ability to engage in school activities, resulting in poor academic performance, and can negatively affect students’ quality of life.8 Therefore, the objective of the present study was to investigate the efficacy of a psycho-educational programme rooted in the theory of rational-emotive behaviour therapy (REBT) in treating depression in a cohort of chemistry education students. REBT theory, developed by Albert Ellis in the 1950s, uses a cognitive behavioural approach to the treatment of depression,9 positing that thoughts affect feelings and in turn influence behaviour and actions.10 REBT seeks to modify irrational and self-defeating thoughts and beliefs, and identifies demandingness, self-downing, awfulising, and low frustration tolerance as the irrational beliefs mediating depressive symptoms.9

Method

This group-based intervention was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Education, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. This study was also conducted in accordance with the research tenets of the American Psychological Association. We obtained informed consent from all individuals included in this research.

We used the G*Power computer software11 to determine the statistical power of the sample, and obtained an a priori power of 0.85 (selected effect size f = 0.30, two groups, three measurements, correlation = 0.5). We assigned participants to groups using random allocation software.12 An independent statistician performed the randomisation, and the allocation concealment was conducted with sealed opaque envelopes numbered sequentially. The remaining 49 students with major depression were referred to counselling. Exclusion criteria were diagnosed psychiatric disorders (panic disorder, bipolar depression, schizophreniform disorder, current substance abuse, and organic brain syndrome), receiving psychotropic medication, and requiring hospitalisation because of the potential of suicide.9

Beck’s Depression Inventory (version II)13 was used to collect qualitative data from the study participants three times (pre-test, post-treatment, and at follow-up). Time between pre-testing and the beginning of treatment period was 4 weeks; at the end of the treatment period, we conducted a follow-up evaluation. Beck’s Depression Inventory is a well-validated and reliable scale of 21 items,14–16 and the internal consistency of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.871 in the present study. Higher Beck’s Depression Inventory scores correlate with a higher level of depression. A demographic questionnaire was used to collect information such as sex, level of study, place of residence, religion, age, and frequency of depression symptoms.

A well-tested protocol for managing depression—the REBT Depression Manual9—was used to aid the participants in the treatment group for 12 weeks. REBT uses cognitive, behavioural, and emotive techniques to assist patients in identifying and altering their depressive beliefs. Students in the control group received counselling services. Univariate analysis of variance and a two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance were performed on data from the pre-test and post-treatment questionnaires to determine the main effects of treatment and time and the time × group interaction effect. There were no missing data. We tested for data normality and violations of assumptions, and the study data were shown to be normally distributed. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

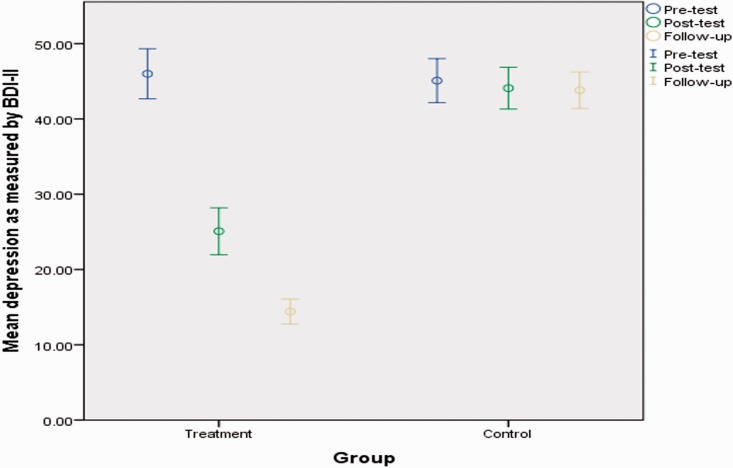

A total of 500 chemistry education undergraduates from all years of study were surveyed for eligibility and possible inclusion in the study. Seventy-two (14.4%) students met the eligibility criteria for major depressive disorder (scored 31 and above in Beck’s Depression Inventory at pre-test). Of these, the first 23 chemistry education undergraduates with major depressive disorder to meet the eligibility criteria were included in the study. Twelve students were randomised to the treatment group and 11 were randomised to the control group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flowchart.

Mean age was 22.25 ± 2.80 years in the treatment group and 21.36 ± 1.75 years in the control group. Four (33.3%) male students and eight (66.7%) female students were in the treatment group; six (54.5%) male students and five (45.5%) female students were in control group. In the treatment group, five students (41.7%) were in their first year of the programme, three (25.0%) were in the second year, and four (33.3%) were in the third year. In the control group, four (36.36%) students were in their first year, one (9.1%) was in the second year, three (27.27%) were in the third year, and three (27.27%) were in the fourth year. Univariate analysis of variance showed that at pre-test, there was no significant difference in the depression scores of students in the treatment and control groups (F(1,21) = .203, P = .657, ηp2 = .010).

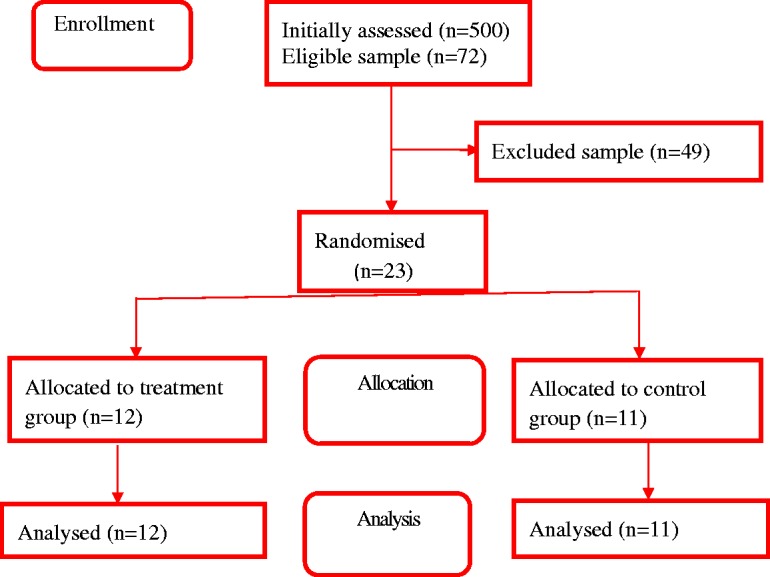

Two-way analysis of variance indicated a significant overall main effect of time on participants’ mean depression scores (F(2,20) = 129.157, P < .001, ηp2 = .928). Similarly, there was a significant difference in mean depression scores between the treatment and control groups (F(1,21) = 131.176, P < .001, ηp2 = .862). The time × group interaction effect was significant (F(2,20) = 109.409, P < .001, ηp2 = .916). Figure 2 illustrates the changes in mean depression scores by group and period of assessment. Treatment was effective in reducing depression scores over time.

Figure 2.

Effect of rational-emotive behaviour therapy on chemistry education undergraduates’ depression scores over time. Bars indicate the 95% confidence interval (CI). BDI-II, Beck’s Depression Inventory, version II.

Discussion

We assessed the efficacy of REBT in reducing depression among chemistry education undergraduate students in a Nigerian university. Several studies have shown the clinical utility of REBT in reducing depression in Nigeria and in other countries.14–16 There was no significant difference in mean depression scores at pre-test between students in the treatment and control arms in our study. Depression scores decreased among the students in the treatment group, suggesting that REBT enabled them to manage their depression. The finding supports studies that reported that REBT was effective in managing depression in both students and other populations.14–19

The present study adds to the existing pool of literature on REBT as effective alternative to pharmacotherapeutic treatment for depression in student populations. Educators and researchers should collaborate with psycho-educational programme specialists to implement REBT in assisting university undergraduates to reduce depression and psycho-social issues that may influence their learning and living experiences.

The present study has some limitations. Because of the small size of the sample, the generalizability of the findings is limited. Another limitation of the study is the lack of sufficient information about participants’ characteristics. We assessed depressive symptoms using only Beck’s Depression Inventory; the assessment of a physician was not performed, and this may be another limitation. To our knowledge, Beck’s Depression Inventory has not been validated in a Nigerian sample. REBT relies on the participant’s commitment and cannot treat severe conditions such as personality disorders. Future studies should endeavour to address these limitations and compare students with and without depression in terms of the collected exposure variables.

Conclusion

Depression and its treatment are topics of relevance in student populations, and the REBT psycho-educational programme was effective in reducing depression scores in our sample.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Ghaed L, Kosnin AM. Prevalence of depression among undergraduate students: gender and age differences. Int J Psychol Res 2014; 7: 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muniz FWMG, Maurique LS, Toniazzo MP, et al. Female undergraduate dental students may present higher depressive symptoms: a systematic review. Oral Dis 2019; 25: 726–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh M, Goel NK, Sharma MK, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress among students of Punjab University, Chandigarh. Nat J Commun Med 2017; 8: 666–671. http://njcmindia.org/uploads/8-11_666-671.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Aloba OO, et al. Depression amongst Nigerian university students: prevalence and sociodemographic correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006; 41: 674–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dabana A, Gobir AA. Depression among Students of Nigerian University: prevalence and Academic Correlates. Arch Med Surg 2018; 3: 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nwefuru BC, Otu MS, Eseadi C, et al. Stress, depression, burnout and anxiety among chemistry education students in Universities in South-East, Nigeria. Journal of Consultancy, Training and Services 2018; 2: 46–54. https://www.jconsulttrainserv.com [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Science Education University of Nigeria Nsukka. Department of science education undergraduate hand book. Nsukka: Prince Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hetolang TL, P’Olak KA. The association between stressful life events and depression among students in a university in Botswana. S Afr J Psychol 2017; 48: 255–267. [Google Scholar]

- 9.David D, Kangas M, Schnur JB, et al. REBT depression manual; Managing depression using rational emotive behavior therapy. Romania: Babes-Bolyai University (BBU), 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Najafi T, Lea-Baranovich D. Theoretical background, therapeutic process, therapeutic relationship, and therapeutic techniques of REBT and CT; and some parallels and dissimilarities between the two approaches. Int J Educ Res 2014; 2: 1–12. https://www.ijern.com/journal/February-2014/13.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, et al. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 2009; 41: 1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saghaei M. Random allocation software for parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med Res Methodol 2004; 4: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck depression inventory manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onuigbo LN, Eseadi C, Ebifa S, et al. Effect of rational emotive behaviour therapy program on depressive symptoms among university students with blindness in Nigeria. J Rat-Emo Cognitive Behav Ther 2018; 37: 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eseadi C, Onwuka GT, Otu M, et al. Effect of rational emotive behavior coaching on depression among type 2 diabetic inpatients. J Rat-Emo Cognitive Behav Ther 2017; 35: 363–382. [Google Scholar]

- 16.David D, Szentagotai A, Lupu V, et al. Rational emotive behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, and medication in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial, posttreatment outcomes, and six‐month follow‐up. J Clin Psychol 2008; 64: 728–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sava FA, Yates BT, Lupu V, et al. Cost‐effectiveness and cost‐utility of cognitive therapy, rational emotive behavioral therapy, and fluoxetine (prozac) in treating depression: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychol 2009; 65: 36–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mousavinik M, Basavarajappa Effect of rational emotive behaviour therapy on depression in infertile women. Zenith International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 2012; 2: 77–84. Available at: http://zenithresearch.org.in/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iftene F, Predescu E, Stefan S, et al. Rational-emotive and cognitive-behavior therapy (REBT/CBT) versus pharmacotherapy versus REBT/CBT plus pharmacotherapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder in youth; a randomized clinical trial. Psychiatry Res 2015; 225: 687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]