Abstract

Introduction

This pre-specified subgroup analysis evaluated the efficacy and safety of budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate metered dose inhaler (BGF MDI) triple therapy versus corresponding dual therapies in the China subgroup of the phase III, double-blind KRONOS study in patients with moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Methods

Patients were randomized 2:2:1:1 to BGF MDI 320/18/9.6 μg, glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate (GFF) MDI 18/9.6 μg, budesonide/formoterol fumarate (BFF) MDI 320/9.6 μg, or budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry powder inhaler (BUD/FORM DPI) 400/12 μg twice daily for 24 weeks. The primary endpoint was change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) over weeks 12–24. Secondary endpoints included symptoms, health-related quality of life, and safety. Rate of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations was an additional efficacy endpoint.

Results

In the China subgroup (n = 432; 22.7% of the KRONOS population), BGF MDI demonstrated nominally significant improvements in the primary endpoint versus BFF MDI (least squares mean (LSM) difference 68 mL; P = 0.0035) and BUD/FORM DPI (LSM difference 78 mL; P = 0.0010) but not GFF MDI (LSM difference − 4 mL; P = 0.8316). BGF MDI demonstrated at least numerical improvements versus comparators in secondary lung function and symptom endpoints. BGF MDI reduced the rate of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations versus GFF MDI (rate ratio 0.41; P = 0.0030), with numerical benefits versus BFF MDI and BUD/FORM DPI. All treatments were well tolerated.

Conclusions

Results demonstrated that BGF MDI showed benefits on lung function (vs inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist), as well as symptoms and exacerbations relative to dual therapies. Findings support BGF MDI use in Chinese patients with moderate to very severe COPD.

Clinical Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02497001.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-020-01266-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Bronchodilator agents, China, Chronic obstructive, Disease exacerbation, Pulmonary disease, Pulmonary function tests

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| This subgroup analysis investigated the efficacy and safety of budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate metered dose inhaler (BGF MDI) triple therapy versus corresponding dual therapies in Chinese patients with moderate to very severe COPD who participated in the phase III, double-blind randomized KRONOS study (NCT02497001). |

| This pre-specified KRONOS subgroup analysis evaluated if the efficacy and safety profile of BGF MDI in the cohort of patients from China was comparable to that in the global KRONOS study population, which included patients from Canada, China, Japan, and the USA. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| BGF MDI showed benefits on lung function versus inhaled corticosteroids/long-acting β2-agonists (ICS/LABA), and symptoms and exacerbations versus ICS/LABA and versus long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA)/LABA. All treatments were well tolerated with no new or unexpected safety findings in this patient cohort. |

| The findings in the China subgroup were generally consistent with those in the overall global population, supporting the use of BGF MDI therapy in Chinese patients with moderate to very severe COPD. |

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third-leading cause of death in China [1], and in 2013 accounted for close to one million deaths—approximately one-third of all global deaths from this disease [2]. COPD prevalence in China is estimated to be around 14% for adults over 40 years of age and is higher in men and rural regions [3, 4]. COPD, therefore, imposes a substantial healthcare burden in China, owing to its prevalence, disease-related disability and mortality, and the aging population [2].

In China, the most commonly prescribed treatment for COPD is dual therapy with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) [5, 6]. For patients experiencing further symptoms or exacerbations on ICS/LABA treatment, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommends the addition of a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) [7]. Only open-triple ICS/LABA + LAMA regimens have been used in clinical practice in China but following the December 2019 approval of the fixed dose combination budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate metered dose inhaler (BGF MDI; Breztri Aerosphere™), delivered using co-suspension delivery technology, this is likely to undergo significant change.

Several triple ICS/LAMA/LABA combinations delivered in a single inhaler have been developed for COPD globally [8–11]. To date, the efficacy and safety of triple ICS/LAMA/LABA combinations in Chinese patients have not been reported.

The phase III KRONOS study evaluated the efficacy and safety of BGF MDI versus dual therapies in patients with moderate to very severe COPD, including a cohort of patients from China [9]. In the global study population, BGF MDI demonstrated benefits on lung function, symptoms, and exacerbations versus glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate (GFF) MDI and budesonide/formoterol fumarate (BFF) MDI dual therapies. This pre-specified subgroup analysis assessed the efficacy and safety of BGF MDI versus GFF MDI and BFF MDI in Chinese participants of the KRONOS study.

Methods

Study Design

KRONOS (NCT02497001) was a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase III trial conducted at 215 sites across Canada, China, Japan, and the USA [9].

The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice, including the Declaration of Helsinki [9], and was approved by institutional review boards and/or independent ethics committees at each site. Patients provided written informed consent.

For the study protocol, see https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/View?id=25410.

Patients

Eligible patients (40–80 years of age) were current/former smokers (at least 10 pack-years) with an established history of COPD and moderate to very severe airflow limitation (post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) at least 25% to less than 80% predicted [9]; an adjustment factor of 0.88 was applied for the Chinese population) [12, 13]. Patients were symptomatic (COPD Assessment Test score at least 10) despite receiving two or more inhaled maintenance therapies for at least 6 weeks before screening. There was no requirement for a history of COPD exacerbations in the year prior to study entry.

Key exclusion criteria included asthma and poorly controlled COPD, non-respiratory diseases, or conditions. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria were published elsewhere [9].

Treatment

Patients were randomized (2:2:1:1) to receive BGF MDI 320/18/9.6 μg, GFF MDI 18/9.6 μg, BFF MDI 320/9.6 μg (all administered from matching blinded MDIs), or open-label budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry powder inhaler (BUD/FORM DPI) 400/12 μg (Symbicort® Turbuhaler; metered dose, equivalent to BUD/FORM delivered dose of 320/9 μg). Treatments were administered as two actuations, twice daily for 24 weeks.

At screening, patients discontinued current COPD medications (including LAMAs and/or LABAs) and received ipratropium bromide maintenance therapy. ICS were continued during screening, provided patients were on a stable dose for at least 4 weeks. Ipratropium and ICS were stopped before randomization. Rescue use of albuterol (salbutamol) was permitted.

Study Endpoints

Findings according to the pre-specified Japan/China statistical analysis approach are reported. Most endpoints were assessed over weeks 12–24. The primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over weeks 12–24. Secondary lung function endpoints included change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over 24 weeks, FEV1 area under the curve from 0 to 4 h (AUC0–4) over weeks 12–24, peak change from baseline in FEV1 within 4 h post-dose over weeks 12–24, and time to onset of action (the first time point at which the change from baseline in FEV1 was greater than 100 mL) on day 1.

Secondary symptom and health-related quality of life endpoints included Transition Dyspnea Index (TDI) focal score over weeks 12–24, change from baseline in St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total score over weeks 12–24, change from baseline (last 7 days of the screening period) in mean daily number of puffs of rescue medication over 24 weeks, and time to clinically important deterioration (CID; defined as time to one of the following criteria: at least 100 mL decrease from baseline in trough FEV1; at least a 4-point increase from baseline in SGRQ total score; TDI focal score of − 1 point or less; or treatment-emergent moderate/severe COPD exacerbation occurring up to week 24). The rate of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations and time to first moderate/severe exacerbation were also assessed.

Safety was evaluated via adverse event monitoring, 12-lead electrocardiograms, clinical laboratory testing, and vital sign measurements. An external, independent clinical endpoint committee adjudicated all reported cases of pneumonia, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and deaths due to suspected MACE against predefined criteria. An external data monitoring committee reviewed the safety assessments at predetermined intervals.

Statistical Analysis

The analyses of the China subgroup within the global KRONOS population were pre-specified. Statistical analyses were considered exploratory; no adjustments for multiplicity were made, and P values are nominal. Endpoints were analyzed as described previously [9] (Supplementary Appendix S1).

Results

Study Population

Of the 1902 randomized patients in the KRONOS global population, 432 (22.7%) were randomized and treated in China (42 centers), and 395 patients (91.4%) from China completed the study. The China modified intent-to-treat, per-protocol (PP), safety and rescue medication user populations comprised 432, 396, 432, and 136 patients, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Baseline demographic characteristics for the China cohort were generally similar across treatment groups (Table 1). Most patients were male (91.9%), and 36.3% had experienced at least 1 COPD moderate/severe exacerbations in the previous year; 94.2% were using ICS at screening. Approximately one quarter (25.9%) had a baseline eosinophil blood count of at least 150 cells/mm3 (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics (China mITT population)

| BGF MDI 320/18/9.6 µg (n = 144) | GFF MDI 18/9.6 µg (n = 144) | BFF MDI 320/9.6 µg (n = 72) | BUD/FORM DPI 400/12 µg (n = 72) | All patients (n = 432) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 63.8 (6.0) | 65.0 (7.0) | 63.7 (6.3) | 65.3 (6.1) | 64.4 (6.4) |

| Male, n (%) | 138 (95.8) | 128 (88.9) | 61 (84.7) | 70 (97.2) | 397 (91.9) |

| Mean body mass index, kg/m2 (SD) | 22.5 (3.4) | 23.2 (3.5) | 22.7 (3.0) | 22.7 (3.0) | 22.8 (3.3) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 40 (27.8) | 44 (30.6) | 20 (27.8) | 14 (19.4) | |

| Median number of pack-years smoked, (range)a | 35.0 (10.0–150.0) | 34.0 (10.0–156.0) | 30.0 (10.0–165.0) | 38.5 (10.0–144.0) | 38.7 (10.0–165.0) |

| COPD severity, n (%) | |||||

| Mild | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.5) |

| Moderate | 59 (41.0) | 61 (42.4) | 31 (43.1) | 32 (44.4) | 183 (42.4) |

| Severe | 73 (50.7) | 67 (46.5) | 34 (47.2) | 33 (45.8) | 207 (47.9) |

| Very severe | 10 (6.9) | 16 (11.1) | 7 (9.7) | 7 (9.7) | 40 (9.3) |

| Mean duration of COPD, years (SD) | 4.7 (5.4) | 4.1 (4.2) | 5.1 (5.5) | 3.9 (3.7) | 4.4 (4.8) |

| Moderate/severe COPD exacerbations in the past 12 months, n (%) | |||||

| 0 | 91 (63.2) | 93 (64.6) | 47 (65.3) | 44 (61.1) | 275 (63.7) |

| 1 | 39 (27.1) | 32 (22.2) | 16 (22.2) | 18 (25.0) | 105 (24.3) |

| ≥ 2 | 14 (9.7) | 19 (13.2) | 9 (12.5) | 10 (13.9) | 52 (12.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.6 (1.1) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.7 (1.2) | 0.6 (1.0) |

| Median (range) | 0 (0–8) | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–8) | 0 (0–8) |

| Baseline eosinophil count | |||||

| Median, cells/mm3 (range) | 90.0 (20.0–1290.0) | 107.5 (15.0–355.0) | 105.0 (20.0–700.0) | 100.0 (35.0–1100.0) | 100.0 (15.0–1290.0) |

| < 150 cells/mm3, n (%) | 108 (75.0) | 107 (74.3) | 53 (73.6) | 52 (72.2) | 320 (74.1) |

| ≥ 150 cells/mm3, n (%) | 36 (25.0) | 37 (25.7) | 19 (26.4) | 20 (27.8) | 112 (25.9) |

| Post-albuterol FEV1, % predicted | |||||

| n | 144 | 143 | 72 | 72 | 431 |

| Mean (SD) | 47.9 (14.3) | 48.8 (14.4) | 48.5 (14.1) | 48.3 (12.7) | 48.4 (14.0) |

| Reversibility to albuterol | |||||

| n | 144 | 143 | 72 | 71 | 430 |

| Mean post-albuterol FEV1 − pre-albuterol FEV1, mL (SD) | 197.6 (118.6) | 185.4 (133.9) | 209.2 (151.9) | 234.4 (121.8) | 201.6 (130.9) |

| Reversibleb, n (%) | 65 (45.1) | 57 (39.6) | 30 (41.7) | 35 (48.6) | 187 (43.3) |

| ICS use at screening, n (%) | 137 (95.1) | 136 (94.4) | 67 (93.1) | 67 (93.1) | 407 (94.2) |

| BDI focal score | |||||

| n | 135 | 126 | 68 | 63 | – |

| Mean (SD) | 6.4 (1.9) | 6.3 (2.0) | 5.9 (2.0) | 6.8 (2.1) | – |

| SGRQ total score | |||||

| n | 139 | 129 | 69 | 65 | – |

| Mean (SD) | 38.7 (15.3) | 38.6 (15.0) | 40.1 (16.3) | 37.7 (17.0) | – |

| Mean CAT total score (SD) | 15.7 (4.0) | 15.5 (3.9) | 15.5 (4.5) | 16.6 (5.6) | 15.8 (4.4) |

| Rescue medication usec | |||||

| n | 45 | 35 | 29 | 25 | – |

| Mean puffs/day (SD) | 2.4 (1.3) | 3.8 (3.3) | 2.9 (2.0) | 3.8 (4.0) | – |

| COPD-related treatments containing MA, BA, or ICS used 30 days prior to screeningd | |||||

| n | 144 | 144 | 72 | 72 | 432 |

| PRN SABA and/or SAMA only, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LAMA only, n (%) | 5 (3.5) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 10 (2.3) |

| LABA only, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ICS only, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| MA/BA, n (%) | 2 (1.4) | 5 (3.5) | 4 (5.6) | 4 (5.6) | 15 (3.5) |

| LAMA/LABA, n (%) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 2 (2.8) | 4 (0.9) |

| ICS/LABA, n (%) | 81 (56.3) | 76 (52.8) | 41 (56.9) | 39 (54.2) | 237 (54.9) |

| ICS/LAMA, n (%) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (2.8) | 0 | 4 (0.9) |

| ICS/MA/BA, n (%) | 55 (38.2) | 57 (39.6) | 24 (33.3) | 28 (38.9) | 164 (38.0) |

| ICS/LAMA/LABA, n (%) | 52 (36.1) | 55 (38. 2) | 24 (33.3) | 26 (36.1) | 157 (36.3) |

| No MA, BA, or ICS, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

BA β2-agonist, BDI Baseline Dyspnea Index, BFF budesonide/formoterol fumarate, BGF budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, BUD/FORM DPI budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry powder inhaler, CAT COPD Assessment Test, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, GFF glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, ICS inhaled corticosteroid, LABA long-acting β2-agonist, LAMA long-acting muscarinic antagonist, MA muscarinic antagonist, MDI metered dose inhaler, mITT modified intent-to-treat, PRN as needed, SABA short-acting β2-agonist, SAMA short-acting muscarinic antagonist, SD standard deviation, SGRQ St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire

aNumber of pack-years smoked = (number of cigarettes each day/20) × number of years smoked

bDefined as improvement in FEV1 post-salbutamol administration (compared with pre-salbutamol administration) of ≥ 12% and ≥ 200 mL

cRescue medication user population

dSafety population; Scheduled use of SAMA is included for every case in which “MA” is explicitly included and scheduled use of SABA is also included for every case in which “BA” is explicitly included

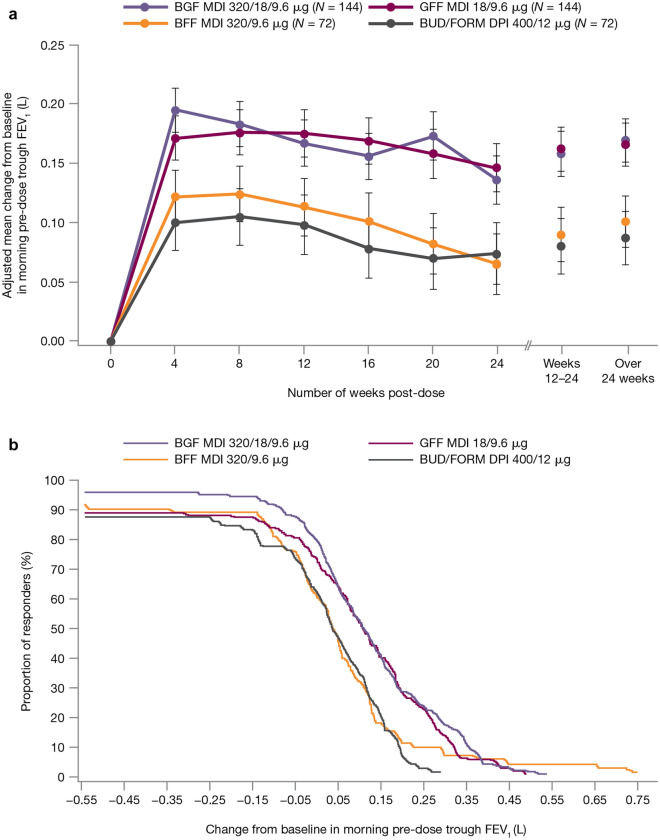

Lung Function

For the primary endpoint (change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over weeks 12–24), BGF MDI demonstrated nominally significant improvements versus BFF MDI (least squares mean (LSM) treatment difference 68 mL; P = 0.0035) and BUD/FORM DPI (LSM difference 78 mL; P = 0.0010) but not GFF MDI (LSM difference − 4 mL; P = 0.8316; Table 2, Fig. 1a). The cumulative proportion of responders for the primary endpoint was generally higher for BGF MDI and GFF MDI than for BFF MDI and BUD/FORM DPI (Fig. 1b). Additionally, BFF MDI was non-inferior to BUD/FORM DPI in the Chinese PP population (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 2.

Primary and secondary lung function endpoints (China mITT population; efficacy estimand unless otherwise stated)

| BGF MDI 320/18/9.6 µg (n = 144) | GFF MDI 18/9.6 µg (n = 144) | BFF MDI 320/9.6 µg (n = 72) | BUD/FORM DPI 400/12 µg (n = 72) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | ||||

| Change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 (weeks 12–24), mL | ||||

| n | 140 | 132 | 69 | 66 |

| LSM (SE) | 158 (18.8) | 162 (18.8) | 90 (22.8) | 80 (23.2) |

| LSM difference vs BGF MDI (95% CI) | NA | − 4 (− 41, 33) | 68 (22, 114) | 78 (32, 125) |

| P value | NA | 0.8316 | 0.0035 | 0.0010 |

| Secondary endpoints | ||||

| Change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 (weeks 12–24), mL (attributable estimand) | ||||

| n | 140 | 132 | 69 | 66 |

| LSM (SE) | 154 (19.3) | 149 (19.2) | 85 (23.3) | 74 (23.7) |

| LSM difference vs BGF MDI (95% CI) | NA | 5 (− 33, 43) | 70 (23, 116) | 81 (34, 128) |

| P value | NA | 0.7859 | 0.0032 | 0.0008 |

| Change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 (over 24 weeks), mL | ||||

| n | 143 | 139 | 71 | 67 |

| LSM (SE) | 169 (18.1) | 166 (18.1) | 101 (21.7) | 87 (22.1) |

| LSM difference vs BGF MDI (95% CI) | NA | 3 (− 32, 37) | 68 (25, 110) | 81 (38, 124) |

| P value | NA | 0.8797 | 0.0018 | 0.0002 |

| FEV1 AUC0–4 (over weeks 12–24), mL | ||||

| n | 140 | 132 | 69 | 66 |

| LSM (SE) | 300 (18.9) | 297 (18.9) | 196 (23.9) | 185 (24.4) |

| LSM difference vs BGF MDI (95% CI) | NA | 3 (− 39, 45) | 104 (53, 155) | 115 (63, 167) |

| P value | NA | 0.8810 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak change from baseline in FEV1 within 4 h post-dose (weeks 12–24), mL | ||||

| n | 140 | 132 | 69 | 66 |

| LSM (SE) | 362 (20.3) | 357 (20.3) | 249 (25.4) | 243 (25.9) |

| LSM difference vs BGF MDI (95% CI) | NA | 4 (− 39, 48) | 113 (59, 166) | 118 (64, 173) |

| P value | NA | 0.8412 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Onset of action on day 1 (change from baseline in FEV1 at 5 min post-dosing), mL | ||||

| n | 122 | 118 | 62 | 59 |

| LSM (SE) | 157 (13.0) | 175 (12.9) | 139 (15.4) | 161 (15.6) |

| Time to onset of action | 5 min | 5 min | 5 min | 5 min |

AUC0–4 area under the curve from 0 to 4 h, BFF budesonide/formoterol fumarate, BGF budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, BUD/FORM DPI budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry powder inhaler, CI confidence interval, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, GFF glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, LSM least squares mean, MDI metered dose inhaler, mITT modified intent-to-treat, SE standard error

Fig. 1.

a Primary lung function endpoint (change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over time) and b cumulative proportion of responders based on the change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over weeks 12–24 (efficacy estimand, China mITT population). Error bars represent standard error values. The proportion of responders represents the percentage of patients with a change from baseline in FEV1 meeting or exceeding the cutoff points shown in the x-axis. BFF budesonide/formoterol fumarate, BGF budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, BUD/FORM DPI budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry powder inhaler, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, GFF glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, MDI metered dose inhaler, mITT modified intent-to-treat

BGF MDI demonstrated nominally significant improvements versus BFF MDI and BUD/FORM DPI for the secondary lung function endpoints, including change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over 24 weeks (P ≤ 0.0018), FEV1, AUC0–4 over weeks 12–24 (P < 0.0001), and peak change from baseline in FEV1 within 4 h post-dose over weeks 12–24 (P < 0.0001; Table 2). In the Chinese PP population, BFF MDI was non-inferior to BUD/FORM DPI for these endpoints (Supplementary Table S1).

For all treatments, time to onset of action on day 1 was within 5 min, with changes from baseline in FEV1 of 157, 175, 139, and 161 mL at 5 min post-dose for BGF MDI, GFF MDI, BFF MDI, and BUD/FORM DPI, respectively.

Symptoms and Health-Related Quality of Life

Changes from baseline in SGRQ total score occurred in all treatment groups (Table 3), with numerical improvements for BGF MDI versus GFF MDI and BFF MDI, and a nominally significant improvement versus BUD/FORM DPI (Table 3). TDI focal scores over weeks 12–24 showed improvements in all treatment groups (range 1.87–3.00); BGF MDI showed a small numerical improvement versus GFF MDI and a nominally significant improvement versus BUD/FORM DPI. BGF MDI demonstrated nominally significant improvement in change from baseline in average daily rescue medication use over 24 weeks versus BFF MDI and numerical improvements versus GFF MDI and BUD/FORM DPI (Table 3). Non-inferiority analyses for BFF MDI to BUD/FORM comparisons are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 3.

Symptom and health-related quality of life endpoints, and CID and exacerbations (China mITT population; efficacy estimand)

| BGF MDI 320/18/9.6 µg (n = 144) | GFF MDI 18/9.6 µg (n = 144) | BFF MDI 320/9.6 µg (n = 72) | BUD/FORM DPI 400/12 µg (n = 72) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change from baseline in SGRQ total score over weeks 12–24 | ||||

| n | 139 | 129 | 69 | 65 |

| LSM (SE) | − 14.0 (1.23) | − 12.0 (1.23) | − 11.5 (1.48) | − 10.5 (1.51) |

| LSM difference vs BGF MDI (95% CI) | NA | − 1.95 (− 4.39, 0.49) | − 2.42 (− 5.37, 0.54) | − 3.42 (− 6.44, − 0.39) |

| P value | NA | 0.1168 | 0.1086 | 0.0270 |

| TDI focal score over weeks 12–24 | ||||

| n | 135 | 126 | 68 | 63 |

| LSM (SE) | 2.84 (0.24) | 2.46 (0.24) | 3.00 (0.29) | 1.87 (0.30) |

| LSM difference vs BGF MDI (95% CI) | NA | 0.38 (− 0.10, 0.86) | − 0.16 (− 0.75, 0.42) | 0.97 (0.37, 1.57) |

| P value | NA | 0.1216 | 0.5813 | 0.0016 |

| Change from baseline in average daily rescue medication use over 24 weeksa | ||||

| n | 45 | 35 | 29 | 25 |

| LSM (SE) | − 1.7 (0.33) | − 1.2 (0.40) | − 0.9 (0.40) | − 1.2 (0.40) |

| LSM difference vs BGF MDI (95% CI) | NA | − 0.52 (− 1.17, 0.12) | − 0.82 (− 1.47, − 0.16) | − 0.49 (− 1.18, 0.20) |

| P value | NA | 0.1119 | 0.0151 | 0.1604 |

| Time to CIDb | ||||

| n (%) with CID | 75 (52.1) | 77 (53.5) | 37 (51.4) | 45 (62.5) |

| Median time to event (weeks) | 24.0 | 20.3 | 20.1 | 12.9 |

| Hazard ratio vs BGF MDI (95% CI) | NA | 0.85 (0.62, 1.17) | 0.96 (0.65, 1.43) | 0.63 (0.44, 0.92) |

| P value | NA | 0.3218 | 0.8508 | 0.0155 |

| Model-estimated rate of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations | ||||

| n (%) with exacerbations | 20 (13.9) | 36 (25.0) | 14 (19.4) | 18 (25.0) |

| Rate per year (SE) | 0.37 (0.09) | 0.90 (0.17) | 0.43 (0.14) | 0.73 (0.20) |

| Rate ratio vs BGF MDI (95% CI) | NA | 0.41 (0.23, 0.74) | 0.87 (0.40, 1.88) | 0.51 (0.25, 1.04) |

| P value | NA | 0.0030 | 0.7196 | 0.0624 |

BFF budesonide/formoterol fumarate, BGF budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, BUD/FORM DPI budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry powder inhaler, CI confidence interval, CID clinically important deterioration, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, GFF glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, LSM least squares mean, MDI metered dose inhaler, mITT modified intent-to-treat, SE standard error, SGRQ St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, TDI Transition Dyspnea Index

aAssessed in the China rescue medication user population (all patients with mean baseline rescue salbutamol use of ≥ 1.0 puff/day)

bCID was defined as a ≥ 100-mL decrease from baseline in trough FEV1; a ≥ 4-point increase from baseline in SGRQ total score; a TDI focal score of –1 point or less; or a treatment-emergent moderate or severe COPD exacerbation occurring up to week 24

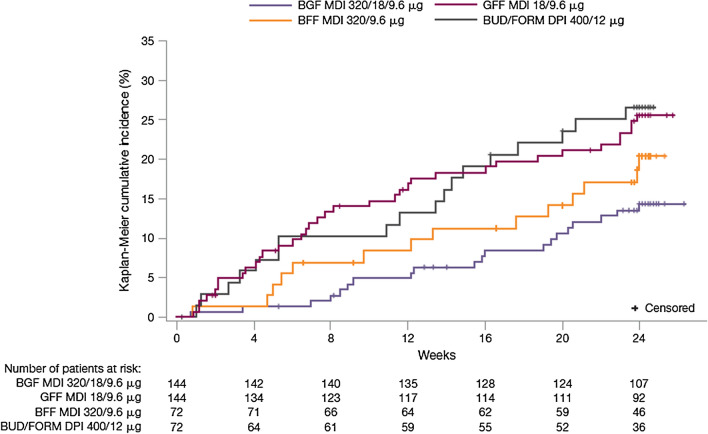

Exacerbations and CID

Annualized rates of moderate/severe exacerbations (Table 3) were nominally significantly lower with BGF MDI versus GFF MDI (rate ratio (RR) 0.41; P = 0.0030) and numerically lower versus BFF MDI (RR 0.87; P = 0.7196) and BUD/FORM DPI (RR 0.51; P = 0.0624). The time to first moderate/severe exacerbation was longest for BGF MDI versus other groups (Fig. 2), and the corresponding risk of a first moderate/severe COPD exacerbation was nominally significantly lower during treatment with BGF MDI versus GFF MDI (hazard ratio (HR) 0.488; P = 0.0106) and BUD/FORM DPI (HR 0.480; P = 0.0248) and numerically lower versus BFF MDI (HR 0.688; P = 0.2848). BGF MDI also increased the median time to a CID event versus other treatment groups (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot for time to first moderate/severe COPD exacerbation (efficacy estimand, China mITT population). BFF budesonide/formoterol fumarate, BGF budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, BUD/FORM DPI budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry powder inhaler, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, GFF glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, MDI metered dose inhaler, mITT modified intent-to-treat

Eosinophil Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup analyses of lung function response showed numerical improvements for BGF MDI versus GFF MDI in the change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 and FEV1 AUC0–4 in patients with blood eosinophil count of at least 150 cells/mm3 (but not patients with fewer than 150 cells/mm3; Supplementary Fig. S3).

No statistical comparisons were performed for COPD exacerbations because of the low number of patients and exacerbation events in both eosinophil subgroups. Unadjusted rates of moderate/severe exacerbations (per year) for BGF MDI, GFF MDI, BFF MDI, and BUD/FORM DPI were 0.42, 0.76, 0.43, and 0.59, respectively, in the fewer than 150 cells/mm3 subgroup; and 0.24, 1.03, 0.49, and 1.13 in the at least 150 cells/mm3 subgroup.

Analysis by continuous baseline eosinophil count with locally weighted scatter-plot smoothing (LOESS) showed that improvements in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 and exacerbation benefits for BGF MDI versus GFF MDI increased as eosinophil levels increased (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Safety

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported by 56.0% of patients, and 23.6% reported TEAEs that were considered treatment-related by the investigator. The most frequently reported TEAEs are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of adverse events (China safety population)

| BGF MDI 320/18/9.6 µg (n = 144) | GFF MDI 18/9.6 µg (n = 144) | BFF MDI 320/9.6 µg (n = 72) | BUD/FORM DPI 400/12 µg (n = 72) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEAEs, n (%) | ||||

| At least 1 TEAE | 82 (56.9) | 84 (58.3) | 32 (44.4) | 44 (61.1) |

| TEAEs relateda to study treatment | 31 (21.5) | 37 (25.7) | 15 (20.8) | 19 (26.4) |

| Serious TEAEs | 12 (8.3) | 19 (13.2) | 2 (2.8) | 11 (15.3) |

| Serious TEAEs relateda to study treatment | 5 (3.5) | 5 (3.5) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (5.6) |

| TEAEs that led to early discontinuation | 4 (2.8) | 5 (3.5) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (5.6) |

| Confirmedb,c MACE | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.4)c | 0 |

| Confirmedb pneumonia | 3 (2.1) | 3 (2.1) | 2 (2.8) | 1 (1.4) |

| Deaths (all causes) | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥ 3% of patients in any treatment arm, preferred term, n (%) | ||||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 35 (24.3) | 16 (11.1) | 12 (16.7) | 13 (18.1) |

| COPDd | 4 (2.8) | 12 (8.3) | 1 (1.4) | 8 (11.1) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (4.9) | 7 (4.9) | 3 (4.2) | 4 (5.6) |

| Toothache | 6 (4.2) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.8) |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 2 (1.4) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (4.2) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 3 (4.2) |

| Osteoporosis | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 3 (4.2) |

Data are n (%), where n is the number of patients who experienced the event

BFF budesonide/formoterol fumarate, BGF budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, BUD/FORM DPI budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry powder inhaler, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, GFF glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event, MDI metered dose inhaler, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

aPossibly, probably, or definitely related to the study drug in the opinion of the investigator

bConfirmed by a clinical endpoint committee

cEvent confirmed as non-fatal myocardial infarction

dWorsening of COPD

Three deaths occurred in the China subgroup: one each in the GFF MDI (unknown cause—adjudicated as probable respiratory cause (COPD) and probably treatment-related), BFF MDI (metastatic encephaloma), and BUD/FORM DPI treatment groups (lumbar vertebra metastases). There was one confirmed MACE (nonfatal myocardial infarction) in the BFF MDI group. Nine patients (2.1%) had confirmed pneumonia; the incidence was similar across treatment groups (range 1.4–2.8%). No clinically meaningful trends were observed in laboratory parameters, vital signs, or electrocardiograms over time in any group.

Discussion

This pre-specified subgroup analysis of the KRONOS study was the first to evaluate an ICS/LAMA/LABA fixed-dose triple combination in Chinese patients with moderate to very severe COPD. The results showed that BGF MDI had benefits on lung function (vs ICS/LABA), as well as symptoms and exacerbations relative to the corresponding LAMA/LABA and ICS/LABA, findings that were generally comparable to the global study population.

The Chinese subgroup generally had similar baseline demographics and clinical characteristics to the global KRONOS population [9]. However, the proportion of men was higher in the Chinese subgroup versus global patients (92% vs 71%), ICS use was more frequent (94% vs 72%, reflecting clinical practice differences), the median eosinophil count was lower (100 vs 150–155 cells/mm3), and in the year before enrollment a larger proportion of patients had experienced at least one COPD exacerbation (36% vs 26%).

Overall, the efficacy findings in Chinese patients were generally consistent with those in the KRONOS global population [9]. In both populations, BGF MDI demonstrated clinically meaningful improvement in lung function versus both BFF MDI and BUD/FORM DPI or pressurized MDI, the latter having a well-characterized efficacy and safety profile [14–17] and is approved for COPD treatment in China. Compared with the LAMA/LABA combination of GFF MDI, BGF MDI demonstrated superiority in the improvement of morning pre-dose trough FEV1 in the global, but not Chinese, population. Continuous analysis of lung function response by eosinophil count in the global population showed that the treatment difference between BGF MDI and GFF MDI for morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over 24 weeks increased with increasing blood eosinophil count, and was evident mainly at eosinophil counts greater than 250 cells/mm3 [9]. Similarly, subgroup analyses of the Chinese population by eosinophil count showed that numerical improvement in lung function with BGF MDI versus GFF MDI was observed in patients with eosinophil counts of at least 150 cells/mm3, and LOESS plots indicated that treatment differences increased as eosinophil levels increased. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution, given the small number of Chinese patients with eosinophil counts of at least 150 cells/mm3.

Reducing exacerbations is an important goal of COPD treatment and a key reason for using ICS-containing maintenance treatments [7]. In Chinese patients, results suggested that BGF MDI markedly reduced the rate of moderate/severe exacerbations relative to GFF MDI (59% reduction), consistent with findings in the global KRONOS population (52% reduction) [9]. A numerical reduction was also noted for BGF MDI versus BFF MDI in both the China and global populations (13% and 18% reductions in annualized exacerbation rates, respectively). These results are notable, given that most Chinese patients did not have exacerbations in the previous year, and had baseline eosinophil counts of less than 150 cells/mm3 (74.1% and 48.2% in the China and global populations, respectively), suggesting that the patient population who can benefit from triple therapy may extend beyond current GOLD guideline recommendations [7].

Robust improvements from baseline in symptomatic endpoints (SGRQ total score, TDI focal score, and rescue medication use) were observed with all treatments but generally favored BGF MDI over dual therapies. Moreover, the improvements from baseline met the minimum clinically important differences for SGRQ total and TDI focal scores [18, 19]. Improvements observed with BGF MDI relative to dual therapy comparators in Chinese patients were generally numerically larger compared with the global population; this may be due to differences in socioeconomic status between these populations, which can affect improvements in patient-reported outcomes in COPD [20].

Overall, treatments were well tolerated, with no new or unexpected safety findings, indicating that the safety profile of BGF MDI in Chinese patients was comparable to the well-established safety profiles of GFF MDI [21–23] and BUD/FORM DPI dual therapies [14–16]. The consistent safety profile between the Chinese and global KRONOS populations reflects the findings of a phase I pharmacokinetics study, which demonstrated that systemic exposures of budesonide, glycopyrronium, and formoterol in healthy Chinese adults were generally similar to those observed in Western subjects [24]. Similar to findings in the global population [9], the incidence of pneumonia was low overall and similar in the budesonide-containing treatment groups versus the GFF MDI group, suggesting that BGF MDI was not associated with an appreciably increased risk of pneumonia relative to dual LAMA/LABA therapy.

Limitations

In interpreting the findings of this analysis, several limitations should be considered, including the relatively small sample size of the China subgroup and the resulting limited statistical power. However, results in the China subgroup were generally consistent with the overall global population results.

Conclusions

This pre-specified subgroup analysis of the KRONOS study showed the benefits of triple therapy with BGF MDI on lung function (vs ICS/LABA), as well as symptoms and exacerbations versus GFF MDI, BFF MDI, and BUD/FORM DPI in Chinese patients with moderate to very severe COPD. All treatments were well tolerated with no new or unexpected safety findings. These findings support the use of BGF MDI in Chinese patients with moderate to very severe COPD.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the patients and their families and the team of investigators, research nurses, and operations staff involved in these studies.

Funding

The KRONOS study was supported by AstraZeneca. The funder of the study had a role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. AstraZeneca funded the Rapid Service fee and open access publication.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Karleen Nicholson, PhD, and Julia King, PhD, on behalf of CMC Connect, McCann Health Medical Communications, funded by AstraZeneca, Gaithersburg, USA in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines [25].

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

All authors were involved in the study conception/design, data acquisition, or data analysis/interpretation, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Prior Presentation

We can confirm that this manuscript is an original piece. Neither the work nor any part of its essential substance, tables or figures have been published in another journal. The research described in this manuscript was presented as a poster at the American Thoracic Society International Conference 2019, which was held in Dallas, TX, USA from 17–22 May 2019. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission to Advances in Therapy, and all conditions of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors have been met.

Disclosures

Chen Wang, Ting Yang, Jian Kang, Li Zhao, and Huijie He have nothing to disclose. Rongchang Chen reports research grants, consultant fees, and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Philips Respironics, Incentive and Boehringer Ingelheim. Pryseley N. Assam, Rong Su, and Shaila Ballal are employees of AstraZeneca. Eric Bourne and Paul Dorinsky are employees of AstraZeneca and hold stock and/or stock options in the company. Kiernan DeAngelis is an employee of IQVIA and as a former employee of AstraZeneca holds stock and/or stock options in the company.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice, including the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by institutional review boards (IRB) and/or independent ethics committees (IEC) at each site. Patients provided written informed consent. Details of the IRBs and IECs are published in the appendix of Ferguson et al. [9].

Data Availability

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.11860902.

References

- 1.Zhou M, Wang H, Zhu J, et al. Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990–2013: a systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;387(10015):251–272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin P, Wang H, Vos T, et al. A subnational analysis of mortality and prevalence of COPD in China from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Chest. 2016;150(6):1269–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang L, Gao P, Bao H, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a nationwide prevalence study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(6):421–430. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30103-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang C, Xu J, Yang L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China (the China Pulmonary Health [CPH] study): a national cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2018;391(10131):1706–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding B, Small M, Bergstrom G, Holmgren U. COPD symptom burden: impact on health care resource utilization, and work and activity impairment. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:677–689. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S123896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Social Survey Research Information. Announcing the results of China’s COPD market research report; 2016. https://www.ssri.com/china/cn/pdf/201609_1.pdf. Accessed Apr 17, 2018.

- 7.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2019 report: global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD; 2019. http://www.goldcopd.org. Accessed June 28, 2019.

- 8.Lipson DA, Barnhart F, Brealey N, et al. Once-daily single-inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1671–1680. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson GT, Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, et al. Triple therapy with budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate with co-suspension delivery technology versus dual therapies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (KRONOS): a double-blind, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(10):747–758. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30327-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papi A, Vestbo J, Fabbri L, et al. Extrafine inhaled triple therapy versus dual bronchodilator therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRIBUTE): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1076–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30206-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh D, Papi A, Corradi M, et al. Single inhaler triple therapy versus inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting β2-agonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRILOGY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10048):963–973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31354-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hankinson JL, Kawut SM, Shahar E, Smith LJ, Stukovsky KH, Barr RG. Performance of American Thoracic Society-recommended spirometry reference values in a multiethnic sample of adults: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) lung study. Chest. 2010;137(1):138–145. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhong N, Zheng J, Wen F, et al. Efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol via a dry powder inhaler in Chinese patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(2):257–265. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.636420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calverley P, Pauwels R, Vestbo J, et al. Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9356):449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szafranski W, Cukier A, Ramirez A, et al. Efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(1):74–81. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00031402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson GT, Tashkin DP, Skärby T, et al. Effect of budesonide/formoterol pressurized metered-dose inhaler on exacerbations versus formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the 6-month, randomized RISE (Revealing the Impact of Symbicort in reducing Exacerbations in COPD) study. Respir Med. 2017;132:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2(1):75–79. doi: 10.1081/COPD-200050513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahler DA, Witek TJ., Jr The MCID of the transition dyspnea index is a total score of one unit. COPD. 2005;2(1):99–103. doi: 10.1081/COPD-200050666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones PW, Gelhorn H, Wilson H, et al. Socioeconomic status as a determinant of health status treatment response in COPD trials. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2017;4(2):150–158. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.4.2.2017.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanania NA, Tashkin DP, Kerwin EM, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of glycopyrrolate/formoterol metered dose inhaler using novel Co-Suspension™ Delivery Technology in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2017;126:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez FJ, Rabe KF, Ferguson GT, et al. Efficacy and safety of glycopyrrolate/formoterol metered dose inhaler formulated using co-suspension delivery technology in patients with COPD. Chest. 2017;151(2):340–357. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipworth BJ, Collier DJ, Gon Y, et al. Improved lung function and patient-reported outcomes with co-suspension delivery technology glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate metered dose inhaler in COPD: a randomized phase III study conducted in Asia, Europe, and the USA. Int J Chron Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;13:2969–2984. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S171835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Q, Hu C, Yu H, et al. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of budesonide/glycopyrronium/formoterol fumarate dihydrate and glycopyrronium/formoterol fumarate dihydrate metered dose inhalers in healthy Chinese adults: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study. Clin Ther. 2019;41:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Battisti WP, Wager E, Baltzer L, et al. Good publication practice for communicating company-sponsored medical research: GPP3. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):461–464. doi: 10.7326/M15-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure.