Abstract

Introduction

To determine patient and rheumatologist preferences for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatment attributes in Spain and to evaluate their attitude towards shared decision-making (SDM).

Methods

Observational, descriptive, exploratory and cross-sectional study based on a discrete choice experiment (DCE). To identify the attributes and their levels, a literature review and two focus groups (patients [P] = 5; rheumatologists [R] = 4) were undertaken. Seven attributes with 2–4 levels were presented in eight scenarios. Attribute utility and relative importance (RI) were assessed using a conditional logit model. Patient preferences for SDM were assessed using an ad hoc questionnaire.

Results

Ninety rheumatologists [52.2% women; mean years of experience 18.1 (SD: 9.0); seeing an average of 24.4 RA patients/week (SD: 15.3)] and 137 RA patients [mean age: 47.5 years (SD: 10.7); 84.0% women; mean time since diagnosis of RA: 14.2 years (SD: 11.8) and time in treatment: 13.2 years (SD: 11.2), mean HAQ score 1.2 (SD: 0.7)] participated in the study. In terms of RI, rheumatologists and RA patients viewed: time with optimal QoL: R: 23.41%/P: 35.05%; substantial symptom improvement: R: 13.15%/P: 3.62%; time to onset of treatment action: R: 16.24%/P: 13.56%; severe adverse events: R: 10.89%/P: 11.20%; mild adverse events: R: 4.16%/P: 0.91%; mode of administration: R: 25.23%/P: 25.00%; and added cost: R: 6.93%/P: 10.66%. Nearly 73% of RA patients were involved in treatment decision-making to a greater or lesser extent; however, 27.4% did not participate at all.

Conclusion

Both for rheumatologists and patients, the top three decision-making drivers are time with optimal quality, treatment mode of administration and time to onset of action, although in different ranking order. Patients were willing to be more involved in the treatment decision-making process.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-020-01258-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Conjoint analysis, Discrete choice experiment, Patient perspective, Preferences, Rheumatoid arthritis, Rheumatologist perspective, Rheumatology, Share decision

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Treatment characteristics may determine its convenience and thereby have impact on patients’ adherence and health-related quality of life. Since patients are more likely to be satisfied and adhere to a treatment that is in line with their preferences, a patient-centered care approach may have significant impact on treatment outcomes. |

| Shared decision-making between physician and patient is a key component of the patient-centered care. The first step in shared decision-making is determining treatment preferences from patients’ perspective. |

| The aim of this study was to determine the preferences of patients and rheumatologists for the attributes of RA treatments and to evaluate their attitude towards shared decision-making. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Both for rheumatologists and patients, the top three decision-making drivers were found to be time with optimal quality, treatment mode of administration and time to onset of action, although in different ranking order. |

| For patients, attributes such as time with optimal quality of life and treatment mode of administration were found to be determinants in treatment selection. |

| Most of RA patients were willing to be more involved in the treatment decision-making process. Although nearly 73% of RA patients indicated that in real-world practice, they were involved in treatment decision-making to a greater or lesser extent, 27.4% of patients were not involved in the decision, with the rheumatologists driving the decisions. |

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is one of the most prevalent autoimmune chronic inflammatory diseases [1, 2]. If sub-optimally treated, RA can lead to joint damage [2], causing different degrees of disability, loss of quality of life (QoL) and even increased mortality [3].

In recent years, there have been important advances in the management and treatment of RA, which have resulted in better patient prognoses [2, 3]. Several efficacious agents are available for RA treatment, including conventional synthetic (cs) disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), biologic (b) DMARDs and targeted synthetic (ts) DMARDs [4].

RA therapies vary in their mechanisms of action and in other characteristics, such as route and frequency of administration or necessity for laboratory monitoring. These characteristics may determine the convenience of the therapy and thereby have impact on patients’ adherence and QoL. Since patients are more likely to be satisfied and adhere to a treatment that is in line with their preferences [5, 6], a patient-centered care approach, defined as ‘providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions,’ may have significant impact on treatment outcomes [7]. In RA, patient and physician assessment of disease severity and treatment response often do not align, suggesting that they focus on different aspects of the disease [8–11]. Values assigned by patients to their health status may be strongly driven not only by clinical aspects such as functional status or symptoms, but also by their beliefs and expectations. Involving patients in the decision-making process is crucial, as they must trade off the perceived benefits of the different treatments with the potential negative consequences. In line with this argument, European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) makes the case for shared decision-making between the patient and the rheumatologist, ensuring inclusion of the patient’s preferences when choosing a suitable medication [12]. In fact, several studies suggest that the number of patients who prefer to participate in decisions during the medical encounter has increased [13]. Hence, it is becoming increasingly important to inform the patient about the different therapeutic options and to offer them the possibility to actively participate in the decision-making process [14], taking into account their perspective and preferences.

Discrete-choice experiments (DCEs) have become the most frequently applied approach to assess patients’ preferences for treatment characteristics in health care research [15, 16]. In a DCE, individuals are asked to choose their preferred option among different (hypothetical) alternatives. This method is based on two assumptions: (1) that treatments can be described in terms of a set of attributes (characteristics) with varying levels and (2) that the priority given by an individual to treatments depends on the nature and level of the attributes that compose them [15]. This methodology has been used successfully in the past to determine patient and/or physician preferences for the attributes of DMARDs in rheumatic diseases [17–20].

The aim of this study was to determine the preferences of patients and rheumatologists for the attributes of RA treatments in Spain and to evaluate their attitude towards shared decision-making (SDM).

Methods

Design

This was an observational, descriptive, exploratory and cross-sectional study based on a DCE. The study was performed within the Spanish healthcare public system from September 2017 to February 2018. The DCE was conducted in accordance with International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) good practice recommendations for conjoint analysis in healthcare [21].

A steering committee constituted by three Spanish experts in RA (CDT, JIC, AUA) led the project.

Study Participants

The study population included RA patients and rheumatologists with experience in the management of RA. Study participants were invited to participate by emails sent by the Spanish Patient Advocacy Group Coordinadora Nacional de Artritis (ConArtritis) (RA patients) and the Spanish Society for Rheumatology (SER) (rheumatologists).

Patients 18 years or older, on DMARD treatment for at least 12 months and who gave their consent to participate were included in the study. The participating rheumatologists had to have at least 3 years of experience in RA management and work in the Spanish Health System.

As per the approach proposed by Orme [22], the minimum sample size necessary for the DCE was based on an estimate of proportion. The criterion of maximum variability was applied, with a 95% confidence interval and 10% margin of error. Patient sample size was estimated on the basis of the adult population in Spain in 2016 (37,408,739) [23] and RA prevalence (0.5%) [24]. The sample size for the rheumatologists was determined using the estimated number of rheumatologists practicing in the public Spanish Health System (629) [25]. A minimum sample of 96 RA patients and 83 rheumatologists was required.

Discrete Choice Experiment

Selection of Attributes and Levels

In DCEs, patients choose between two hypothetical treatment alternatives described by attributes (characteristics) and their corresponding levels (different possible values of the attributes) [15]. To select the attributes and levels for the DCE, three consecutive steps were conducted: (1) literature review; (2) RA patient focus group discussion; (3) rheumatologist focus group discussion.

Literature Review

Key terms related to the disease, treatment and stated-preferences studies were used to search the international Pubmed/Medline database. Publications referring to patient and physician preferences in relation to RA treatment as well as those that referred to their perspectives on the management of the disease were consulted. Articles published in Spanish or English up to 9 March 2016 were reviewed.

The results of the literature review [26] were used to provide inputs for discussion in both focus groups.

Focus Groups (Patients and Rheumatologists)

Following the literature review, two focus groups, one with RA patients and one with rheumatologists, were used to validate and assess the relevance of the attributes and levels identified in the literature as well as to identify attributes not previously described but that were relevant to the Spanish RA population.

A total of five RA patients, invited by the patient advocacy group “ConArtritis,” participated in the patient focus group. After the completion of a brief questionnaire on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, the list of attributes and levels derived from the literature review was presented to the patients to discuss them. During the discussion, patients were encouraged to add new attributes and levels not previously identified in the literature review, but relevant for them. When all attributes and levels were identified, a ranking exercise was then performed to determine the relevance of the attributes and levels proposed. The interpretation of the qualitative analysis and the analysis of the ranking exercises allowed identifying the most important attributes.

After the patient focus group, one with four experienced rheumatologists (including the members of steering committee) was conducted. The objectives of this focus group were to discuss the relevance of the attributes identified in the literature review and proposed by patients from the focus group and define the attributes and levels to be included in the DCE.

As a result of the literature review and the two focus groups, seven attributes composed of two or four levels each were selected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Attributes and levels used in the discrete choice experiment

| Attribute | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time with optimal QoL | 10 years | 7 years | 5 years | 2 years |

| Substantial improvement of RA symptoms | 9 out of 10 patients | 7 out of 10 patients | 5 out of 10 patients | 3 out of 10 patients |

| Onset of treatment action | 7 days | 15 days | 1 month | 3 months |

| Severe adverse events | 1 out of 100 patients | 5 out of 100 patients | ||

| Mild adverse events | 10 out of 100 patients | 30 out of 100 patients | ||

| Mode of administration | Daily oral | Weekly subcutaneous | Monthly subcutaneous | Monthly intravenous |

| Additional cost/month for treatment | 0 | 10 | 20 | 50 |

QoL quality of life, RA rheumatoid arthritis

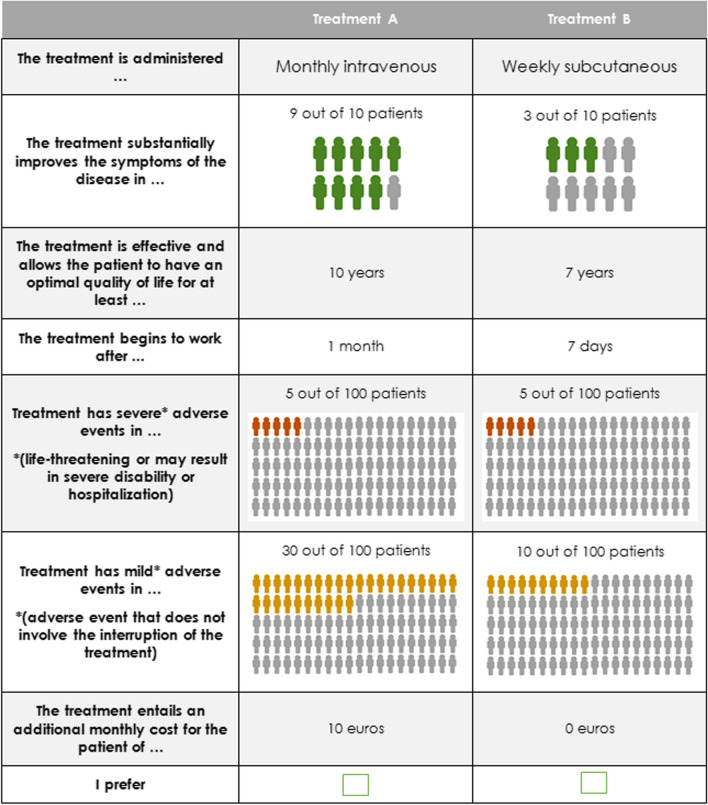

Experimental Design

The combinations of attributes and levels that defined each treatment pair were determined by an experimental design developed according to ISPOR recommendations. The DCE design encompassed two properties: orthogonality and balance [21]. The orthogonal design guarantees that all attribute levels vary independently, and the balance design ensures that each attribute level occurs the same number of times. The pairs of choice (Fig. 1) were generated by the mix and match algorithm [27]. To avoid dominance between alternatives, the resulting scenarios were evaluated for dominated alternatives.

Fig. 1.

Example of pair of choice (scenario) presented to RA patients

A total of eight scenarios were created, which formed a single block. Additionally, an initial control scenario, in which one treatment was clearly superior to the other (dominant option), was included. Participants who answered this question incorrectly were excluded from analysis as this indicates that they did not comprehend what is required from them in this study [28].

Survey Instrument

Two online surveys were generated, one for patients and one for rheumatologists. Both contained the same DCE choice scenarios and included an information form and an electronic informed consent form that had to be read and accepted before completing the questionnaire. In addition, both questionnaires initially included a series of questions to verify that participants met the selection criteria.

The rheumatologist questionnaire included a set of sociodemographic and professional variables to characterize them. The patient questionnaire included sociodemographic and clinical variables, and a Health Assessment questionnaire (HAQ) to assess the patient’s functional status [29]. A set of ad hoc questions was also included to collect the patient’s perception of: (1) the current degree of involvement in treatment decision-making and their expectations about their involvement [30]; (2) the satisfaction with the information received about the disease, current treatment and therapeutic alternatives (Likert scale: 1 = not at all satisfied; 5 = very satisfied).

Statistical Analyses

Stata version 14 and R version 3.4.1 were used for the statistical analysis. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant for all statistical tests.

For the descriptive analysis of the qualitative variables, the relative and absolute frequencies were calculated, and for the quantitative variables central tendency and dispersion measures were used for each group of participants.

To assess the utility and the relative importance (RI) value given to the attributes of RA treatments by patients and rheumatologists, a conditional logit model [31] was used. Respondents who did not select the dominant option in the control scenario were excluded. Substantial improvement of RA symptoms, time with optimal QoL, severe and mild adverse events and additional cost per month attributes were linearly transformed. Coefficients obtained in the conditional logit model represented the partial utilities, i.e., the preference for each level within each attribute. A statistically significant coefficient indicates that the attribute level influences the respondents’ treatment decisions. The RI of each attribute, defined as the relative preference weight for the attribute over all attributes, was calculated as the quotient between the range of the partial utility values of the attribute and the sum of the partial utility values ranges of the whole set of attributes. The greater the RI among the seven attributes, the more significant the attribute was for decision-making.

To evaluate which characteristics of the participants influenced decision-making, a hierarchical cluster analysis was applied to each group of participants based on DCE response, i.e., the scenario selected in each pairs of choice [32]. Since scenario choices were dichotomous, a binary distance was applied. Stats and Nbclust packages were used to determine the optimal number of clusters [33, 34]. To assess differential characteristics between the clusters obtained, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of each cluster were compared.

Maximum acceptable risk (MAR) was estimated as the quotient between the utility associated with a clinical benefit attribute (substantial improvement of RA symptoms) and the utility associated with risk (severe adverse events) [35].

To establish differences between the patient’s current role in the decision-making process and their expectations about their involvement in it, the answers given in the ad hoc questionnaire [30] were compared using McNemar Bowker’s test [36].

Statement of Ethics Compliance

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was developed to ensure that Good Clinical Practices were observed, in keeping with ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline principles. The study protocol was submitted to the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices and to the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda Hospital for approval. An electronic informed consent form was read and accepted by all participants before completing the questionnaire.

Results

Participants’ Characteristics

A total of 94 rheumatologists and 153 RA patients participated in the study. Due to incomplete data or incorrect responses to the control scenario, 4 rheumatologists and 16 RA patients were excluded from the analysis. A total of 90 rheumatologists [52.2% women; mean years of experience in RA 18.1 years (SD: 9.0); seeing an average of 24.4 RA patients/week (SD: 15.3); 75.6% working in a 200 - 1000 bed hospital] and 137 RA patients [mean age: 47.5 years (SD: 10.7); 84.0% women; mean time since diagnosis of RA 14.2 years (SD: 11.8) and time in treatment 13.2 years (SD: 11.2), mean HAQ score 1.2 (SD: 0.7)] were included in the final data analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patients sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (n = 137)

| Characteristic | % of patients or mean |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 47.5 (10.7) |

| Female, % | 84 |

| Marital status, % | |

| Married/in a relationship | 67.9 |

| Single/separated/divorced/widower | 32.1 |

| Level of education, % | |

| Primary school | 10.2 |

| Secondary school | 32.1 |

| University or higher | 51.1 |

| Other | 6.6 |

| Employment status, % | |

| Employed, full or part time | 47.7 |

| Non-employeda | 52.3 |

| Incomes, % | |

| ≤ 2500€/month | 83.9 |

| > 2500€/month | 1.5 |

| Unknown/not answered | 14.6 |

| Time since diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 14.2 (11.8) |

| Time in RA treatment, years, mean (SD) | 13.2 (11.2) |

| Time in current treatment, years, mean (SD) | 6.2 (7.8) |

| Mode of administration, % | |

| Oral | 21,9 |

| Subcutaneous | 18.3 |

| Intravenous | 4.4 |

| Oral + subcutaneous | 46.7 |

| Oral + intravenous | 8 |

| Subcutaneous + intravenous | 0.7 |

| Other medicines received/day, mean (SD) | 4.0 (3.4) |

| HAQ, mean (SD) | 1.2 (0.7) |

RA rheumatoid arthritis, SD standard deviation, HAQ Health Assessment Questionnaire

aIncluded: long-term sick-leave/disabled/unemployed/student/household/retired

Rheumatologists and Patients’ Preferences for RA Treatment Attributes

Partial Utilities

The main results of the DCE are shown in Table 3. Partial utilities denote the importance assigned to each level within an attribute. A positive partial utility for an attribute level indicates a preference for that level over the reference level, while a negative partial utility implies a lesser preference. Accordingly, the higher the partial utility, the greater the preference. It was not possible to directly compare partial utility values between attributes. The attribute levels with a statistically significant influence in patient/rheumatologist treatment choice are those with a p value < 0.05.

Table 3.

Patient and rheumatologist DCE results

| Attribute | Level | Patients (n = 137) | Rheumatologists (n = 90) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial utility | SE | p value* | Partial utility | SE | p value* | ||

| Time with optimal QoL | 1 year | 0.244 | 0.036 | < 0.001 | 0.195 | 0.045 | < 0.001 |

| 10 years | 2.44 | 1.951 | |||||

| 7 years | 1.708 | 1.366 | |||||

| 5 years | 1.22 | 0.976 | |||||

| 2 years | 0.488 | 0.39 | |||||

| Substantial improvement of RA symptoms | 1% patientsa | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.251 | 0.015 | 0.004 | < 0.001 |

| 9 out of 10 patients (90%) | 0.303 | 1.35 | |||||

| 7 out of 10 patients (70%) | 0.235 | 1.023 | |||||

| 5 out of 10 patients (50%) | 0.168 | 0.731 | |||||

| 3 out of 10 patients (30%) | 0.101 | 0.438 | |||||

| Onset of treatment action | 7 days (ref) | 0.000 | – | – | 0.000 | – | – |

| 15 days | − 0.372 | 0.285 | 0.193 | − 0.602 | 0.356 | 0.091 | |

| 1 month | − 0.562 | 0.255 | 0.027 | − 1.083 | 0.326 | 0.001 | |

| 3 months | 0.194 | 0.275 | 0.481 | − 0.715 | 0.342 | 0.036 | |

| Severe adverse events | 1% patientsa | − 0.156 | 0.058 | 0.007 | − 0.182 | 0.074 | 0.014 |

| 1 out of 100 patients (1%) | − 0.156 | − 0.182 | |||||

| 5 out of 100 patients (5%) | − 0.781 | − 0.908 | |||||

| Mild adverse events | 1% patientsa | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.856 | − 0.014 | 0.018 | 0.444 |

| 10 out of 100 patients (10%) | 0.025 | − 0.139 | |||||

| 30 out of 100 patients (30%) | 0.076 | – 0.416 | |||||

| Mode of administration | Daily Oral (ref) | 0.000 | – | – | 0.000 | – | – |

| Weekly subcutaneous | − 1.394 | 0.372 | < 0.001 | − 1.683 | 0.461 | < 0.001 | |

| Monthly subcutaneous | − 0.375 | 0.364 | 0.302 | − 0.249 | 0.442 | 0.574 | |

| Monthly intravenous | − 0.956 | 0.366 | 0.009 | – 0.446 | 0.458 | 0.331 | |

| Additional cost/month for treatment | Additional 1€/month | − 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.102 | – 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.296 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 10 | − 0.119 | – 0.092 | |||||

| 20 | − 0.238 | − 0.185 | |||||

| 50 | − 0.594 | − 0.462 | |||||

Bold values indicate that there is statistical significance (p < 0.05)

QoL quality of life, RA rheumatoid arthritis, SE standard error

aRefers to a 1% of increase of the proportion of patients

Partial utility of the attributes that were then linearly transformed (time with optimal QoL, RA symptoms, severe and mild adverse events and additional cost per month) must be interpreted as one unit increases, 1 year for time with optimal QoL attribute or a 1% increase in the proportion of patients for the rest.

Partial utilities of the levels of onset of treatment action and mode of administration are negative. This means that these levels are less preferred than the level of reference: 7 days and daily oral administration, respectively. With respect to the onset of treatment action, 1 month is statistically less preferred by patients and rheumatologists. For the latter, 3 months is also statistically significant. Notice that for patients, weekly subcutaneous and monthly intravenous administrations were statistically less preferred than daily oral administration, while for rheumatologists only weekly subcutaneous administration was significantly less preferred.

The probability of mild adverse events related to treatment and the associated additional cost/month were not identified as treatment decision-making drivers.

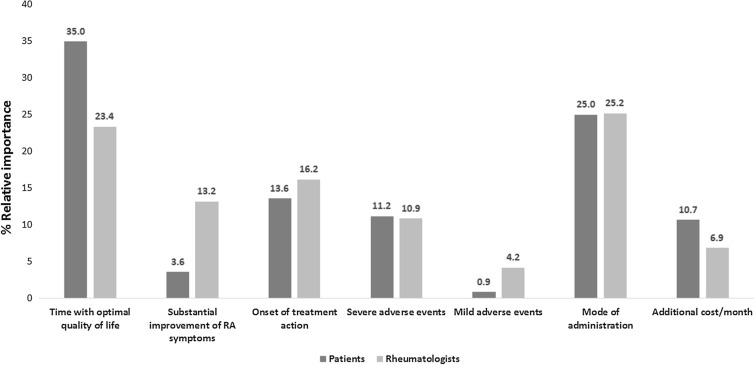

Relative Importance

For patients, time with optimal QoL was the most important attribute in RA treatment selection followed by mode of administration. The onset of treatment action, probability of severe adverse events and additional cost/month for treatment had a similar weight in the choice (RI: 13.6%, 11.2% and 10.7%, respectively). Overall, during the treatment decision-making process, patients conferred much more importance to treatment benefit-related attributes (time with optimal QoL + substantial improvement of RA symptoms) than to safety attributes (severe adverse events and mild adverse events). For rheumatologists, the mode of administration was the most important attribute followed by time with optimal QoL and the onset of treatment action (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Relative importance of attributes for patients and rheumatologists

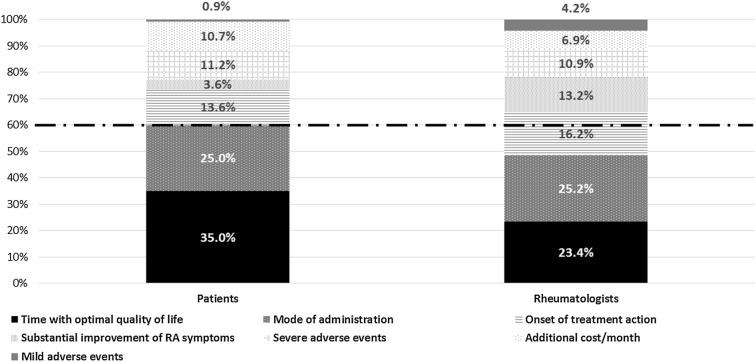

For rheumatologists and patients, treatment benefits (‘time with optimal QoL’ and ‘substantial improvement of RA symptoms’) accounted for 38.6% and 36.6% of the decision, respectively. For both, these attributes had a greater weight in the decision than those related to safety (patients: 38.7% vs. 12.1%; rheumatologists: 36.6% vs. 15.1%). It is important to note that, for patients, time with optimal QoL provided by the treatment, and its mode of administration determined 60% of the decision, while for rheumatologists, the decision was driven mainly by time with optimal QoL, mode of administration and onset of action (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Relative importance of attributes for patients and rheumatologists

Cluster Analysis

Based on the choices made in the DCE, i.e., scenario selected by participants in each pairs of choices, the patients’ sample was segmented into two subgroups (clusters). The analysis of the patients’ characteristics of the two clusters only showed statistically significant differences for the route of administration (p = 0.008) (Supplementary data Table S1). The estimates of the utility values of the different routes of treatment administration according to their current route of administration suggest that the current route of treatment administration may influence patient preference, showing a trend towards a greater preference for the route of administration in which the patient is currently receiving treatment (Supplementary data Figure S1).

No clusters were identified for rheumatologists.

Maximum Acceptable Risk

Differences between patients and rheumatologist were observed regarding the maximum acceptable risk. While rheumatologists were willing to accept an increase of 0.08% of risk to suffer a severe adverse event for a 1% increase in the chance of a mayor symptom improvement, patients' maximum acceptable risk was lower (0.02%).

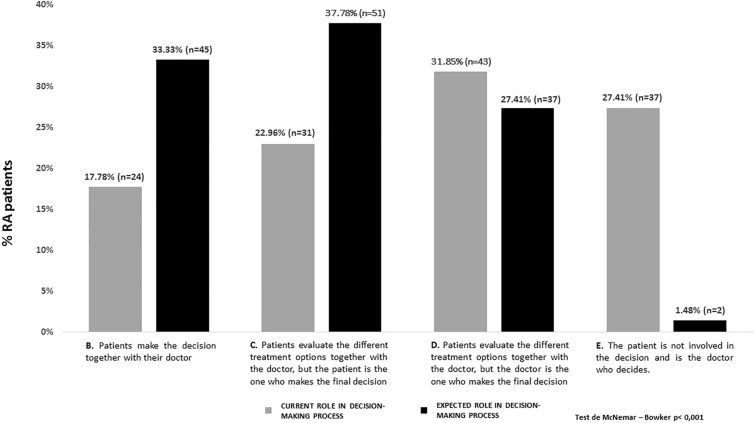

Patients’ Perception of Their Involvement in Treatment Decision-Making

Statistical differences were observed between the RA patients’ current role and the expected role in the treatment decision-making process (McNemar-Bowker’s test; p < 0001). In real-word practice nearly 73% of patients were involved in the treatment decision-making to a greater or lesser extent: 17.8% made the decision together with their doctor, 23.0% evaluated the different treatment options together with the doctor and the patient was the one who made the decision, and 31.8% evaluated the different treatment options together with the doctor but the doctor was the one who made the decision. However, 27.4% of patients were not involved in the decision (the rheumatologists made decisions). Related to their expectations about their involvement, it is important to note that 98.5% of patients were willing to be involved in the treatment decision-making process, and 71.1% of them would like to be the ones who make the decision (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

RA patients’ current and expected role in the decision-making process

Patients’ Satisfaction with the Information Received

The majority of patients were satisfied with the information received about the disease (60.3% of patients very satisfied/satisfied) and their current RA treatment (64.7% very satisfied/satisfied). However, less satisfaction was reported by patients with information received regarding therapeutic options (35.8% very satisfied/satisfied).

Discussion

Patients and physicians have different perceptions and beliefs about health and illness [8–11]. Adequate understanding of patients’ health perceptions and risk tolerance may assist physicians in the decision-making process at the time of the clinical encounters by helping them take into account benefit-risk ratios that are important to patients [11]. Therefore, in recent years, the healthcare systems in developed countries have been evolving into a patient-centered care model, in which patients take a more active role in making decisions that affect them [37], promoting their involvement in the healthcare decision-making process. Their participation can occur at multiple levels: individual (SDM), policy (patient expert on panels) and commissioning (incorporating patient preferences in health technology assessment or health state evaluation) [16]. Stated preference studies, such as DCE, are increasingly advocated as one of the most reliable and valid techniques available for quantifying preferences in health care [15, 16].

In RA, the treat-to-target approach has led health care professionals to focus on inflammatory disease, whereas patients are mainly concerned about pain and fatigue reduction and maintaining physical and mental function [38]. Better knowledge of patients’ preferences may help healthcare professionals improve disease management. By providing information related to patients’ most salient concerns, treatment selection can be in line with their preferences and therefore, improve their satisfaction and adherence to treatment.

Several studies have investigated preferences of RA patients [17–20, 39–43]; however, none of them include an attribute related to treatment benefits defined as time with optimal QoL. There is ample evidence that RA negatively impacts patients’ QoL [44]. In fact, previous works have found that many RA patients value QoL more than disease-related variables such as inflammatory biomarkers or joint counts [45]. Therefore, it is not surprising that our results pointed out ‘time with optimal QoL’ as one of the most important attributes, achieving a higher relative importance than ‘substantial improvement of RA symptoms.’ These results suggest that patients place greater value on medium- to long-term improvement than a one-off improvement in symptoms. For rheumatologists and patients, attributes related to treatment benefits are key drivers. Mode of administration has also been identified as a decision driver both for RA patients and rheumatologists. This result supports findings of previous studies that show that mode of administration (route and frequency) has a strong impact on patients’ decisions, with oral administration being the most preferred [17, 19, 39]. Few studies have studied the influence of onset of treatment action on treatment decision-making [46]. Our results suggested that a faster time for the drug to start working is preferred, and this attribute may impact treatment selection, mainly for rheumatologists.

Other studies available in the literature identified cost [20, 40] and safety [17, 19, 20, 43] as main drivers of treatment selection. However, in our study, additional treatment cost and safety seemed to be less valued, with these attributes being the ones with the least relative importance. One of the possible reasons for the discrepancy observed in relation to the importance of cost in decision-making is the magnitude of the difference in costs proposed in the DCE. In our study, the additional cost ranged from €0 to €50/month, while in previous studies the cost ranged from €500 to €1500/month [20] or from €0 to a threefold increase on health care taxes (€260/month) [40]. Regarding safety, differences may be due to the attributes used to describe safety in previous studies (‘probability of suffering serious infections’ [20], ‘generalized adverse events’ [20, 40], ‘local adverse events’ [20], ‘reactions at the site of drug administration’ [40], ‘to stop the medication due to a side effect by 6 months’ [43], ‘chance of serious treatment reaction’ [18, 19] or ‘mild treatment reaction’ [18]), which varied from the ones used in this survey (‘percentage of patients that suffer severe or mild adverse events’) and may be interpreted in a different way. The lesser importance attached to safety attributes may also be explained by the inclusion of the ‘optimal QoL’ concept of the lack of side effects.

The information provided by preferences studies is not only relevant to improving health decision-making, but can also be useful for defining new drug development strategies, more closely aligned with patients’ preferences. Preference studies conducted during preclinical development may contribute to seeking early patient input on what outcomes are important; during clinical trial design they may help define patient-relevant endpoints and study enrolment criteria; or in post-market approval studies, they may support the formulation of product communication and marketing strategies [47].

Shared decision-making (SDM) is the pinnacle of patient-centered care [48]. SDM increases patient knowledge, reduces anxiety over the care process and improves health outcomes [49] by ensuring that medical care better aligns with patients’ preferences and values. The results of the study highlighted that RA patients were willing to be involved in treatment decision-making. Although most of them are involved in the decision-making process, nearly 30% maintain a passive attitude, with the rheumatologist being the one who makes the decision for them. The use of patient decision aids (PDA) in RA may help rheumatologists to involve patients in decision-making by providing detailed information related to the disease and its treatment options and guiding patients through this process [50]. Since PDA provide detailed information about the therapeutic options, its use in clinical practice would cover the demand for more information on therapeutic options found in the study.

This study has some limitations, some of which are inherent to its design. First, although DCE is the recommended approach and is widely used to assess patient preferences for treatment characteristics, real-world treatment decision-making may differ from the stated choices provided during DCE because of the influence of treatment attributes that were not included in the study as well as other influences on decision making such as lifestyle or family environment. Therefore, although the attributes presented were confirmed as being the most relevant for treatment decision-making in RA, it cannot be excluded that attributes not included may also be relevant and play a role in treatment decision-making. Moreover, there is some uncertainty associated with the interpretation by patients of the attributes presented within the scenarios, mainly time with optimal QoL and onset of treatment action, and how it may affect the results. Finally, since RA patients were invited to participate by a Patient Advocacy Group, they may not be representative of the RA population and limitations in the generalizability of results cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

Our results provide knowledge related to patient and rheumatologist preferences for treatment, showing some differences between both perspectives. For rheumatologists, in addition to efficacy, treatment mode of administration and time to onset of action are decision-making drivers. For patients, efficacy defined as time with optimal QoL and treatment mode of administration are determinants in treatment selection.

The knowledge of patients’ preferences and the evidence that patients are willing to be involved in treatment decision-making that have been gained by this study may contribute to and facilitate the adoption of a patient-centered care model.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Spanish Patient Advocacy Group Coordinadora Nacional de Artritis (ConArtritis) and the Spanish Society of Rheumatology for their support during the conduct of the study. Also, they are very grateful to all the rheumatologists and patients who participated in the study.

Funding

This research, the Rapid Service and Open Access Fees were supported by Eli Lilly & Co, Madrid (Spain).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Silvia Díaz, Tatiana Dilla, José Antonio Sacristán and José Inciarte-Mundo are employees of Eli Lilly & Co. Marta Comellas, Miriam Prades and Luis Lizán work for an independent research entity that received funding from Eli Lilly & Co to coordinate and conduct the study and to write up the manuscript. Cesar Díaz-Torné, Ana Urruticoechea-Arana and José Ivorra-Cortés have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was developed to ensure that Good Clinical Practices were observed, in keeping with ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline principles. The study protocol was submitted to the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices and to the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda Hospital for approval. An electronic informed consent form was read and accepted by all participants before completing the questionnaire.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.11830479.

References

- 1.Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2016;388:2023–2038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Barton A, Burmester GR, Emery P, Firestein GS, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2018;4(18001):1–23. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanmartí R, García-Rodríguez S, Álvaro-Gracia JM, Andreu JL, Balsa A, Cáliz R, et al. Actualización 2014 del Documento de Consenso de la Sociedad Española de Reumatología sobre el uso de terapias biológicas en la artritis reumatoide. Reumatol Clín. 2015;11(5):279–294. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):960–977. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasma A, van’t Spijker A, Hazes JMW, Busschbach JJV, Luime JJ. Factors associated with adherence to pharmaceutical treatment for rheumatoid arthritis patients: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bemt BJ van den, Zwikker HE, Ende CH van den. Medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a critical appraisal of the existing literature. Expert Rev Clin Immunol [Internet]. 2014;337–51. Disponible en: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1586/eci.12.23?journalCode=ierm20#.Vegj7PmeDGc. Accessed 8 Apr 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Voshaar MJH, Nota I, Van De Laar MAFJ, Van Den Bemt BJF. Patient-centred care in established rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29(4–5):643–663. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen H, Ralph Schumacher H, Li X, Gu J, Ma L, Wei H, et al. Comparison of expectations of physicians and patients with rheumatoid arthritis for rheumatology clinic visits: a pilot, multicenter, international study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15(4):380–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Mits S, Lenaerts J, Vander Cruyseen B, Mielants H, Westhovens R, Durez P, et al. A Nationwide Survey on Patient’s versus Physician’s Evaluation of Biological Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis in Relation to Disease Activity and Route of Administration: The Be-Raise Study. Plose One. 2016;11(11):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markenson JA, Koenig AS, Feng JY, Chaudhari S, Zack DJ, Collier D, et al. Comparison of physician and patient global assessments over time in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective analysis from the RADIUS Cohort. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19:317–323. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3182a2164f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suarez-Almazor ME, Conner-Spady B, Kendall CJ, Russell AS, Skeith K. Lack of Congruence in the Ratings of Patients’ Health Status by Patients and Their Physicians. Med Decis Mak. 2001;21(2):113–121. doi: 10.1177/02729890122062361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, Buch M, Burmester G, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(3):492–509. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neame R, Hammond A, Deighton C. Need for information and for involvement in decision making among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a questionnaire survey. Arthritis Care and Res. 2005;53:249–255. doi: 10.1002/art.21071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Muhlbacher A, Regier DA, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value Heal. 2013;16(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soekhai V, de Bekker-Grob EW, Ellis AR, Vass CM. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: past, present and future. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(2):201–226. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0734-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nolla J, Rodríguez M, Martin-Mola E, Raya E, Ibero I, Nocea G, et al. Patients’ and rheumatologists’ preferences for the attributes of biological agents used in the treatment of rheumatic diseases in Spain. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1101. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S106311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poulos C, Hauber AB, González JM, Turpcu A. Patients’ willingness to trade off between the duration and frequency of rheumatoid arthritis treatments. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66(7):1008–1015. doi: 10.1002/acr.22265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Louder AM, Singh A, Saverno K, Cappelleri JC, Aten AJ, Koenig AS, et al. Patient preferences regarding rheumatoid arthritis therapies: a conjoint analysis. Am Heal Drug Benefits. 2016;9(2):84–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Augustovski F, Beratarrechea A, Irazola V, Rubinstein F, Tesolin P, Gonzalez J, et al. Patient preferences for biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis: a discrete-choice experiment. Value Heal. 2013;16(2):385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Heal. 2011;14(4):403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orme B. Getting started with conjoint analysis: strategies for product design and pricing research. 2. Madison, WI: Research Publishers LLC; 2010. pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Estimaciones de la población actual de España a 1 de enero de 2016. Available at: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176951&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735572981. Accessed 21 Sept 2016.

- 24.Carmona L, Ballina J, Gabriel R, Laffon A, EPISER Study Group The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the general population of Spain: results from a national survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(11):1040–1045. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.11.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.González López-Valcárcel B, Barber Pérez P, Suarez Vega R. Oferta y necesidad de especialistas médicos en España (2010–2025).2011; 230.

- 26.Dilla T, Rentero M, Comellas M, Lizan L, Sacristán J. Patients’ preferences for rheumatoid arthritis treatments and their participation in the treatment decision-making process: a systematic review of the literature. Value Heal. 2015;18(7):A652. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.2348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aizaki H. Basic functions for supporting an implementation of choice experiments in R. J Stat Softw. 2012;50:1–24. doi: 10.18637/jss.v050.c02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . How to conduct a discrete choice experiment for health workforce recruitment and retention in remote and rural areas: a user guide with case studies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Esteve-Vives J, Batlle-Gualda E. Reig A (1993) Spanish version of the Health Assessment Questionnaire: reliability, validity and transcultural equivalency. Grupo para la Adaptación del HAQ a la Población Española. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(12):2116–2122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solari A, Giordano A, Kasper J, Drulovic J, van Nunen A, et al. Role preferences of people with multiple sclerosis: image-revised, computerized self-administered version of the control preference scale. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mcfadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 105–142. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Everitt B, Landau S, Leese M, Stahl D. Cluster analysis. 5. Amsterdam: Wiley; 2011. p. 346. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Core Team R . R: A language and environment for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna: Core Team R; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charrad M, Ghazzali N, Boiteau V, Niknafs A. NbClust: an R package for determining the relevant number of clusters in a data set. J Stat Softw. 2014;61(6):1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v061.i06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson FR, Özdemir S, Mansfield C, Hass S, Miller DW, Siegel CA, et al. Crohn’s disease patients’ risk-benefit preferences: serious adverse event risks versus treatment efficacy. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(3):769–779. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowker AH. A Test for symmetry in contingency tables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1948;43(244):572–574. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1948.10483284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sacristán J. Patient-centered medicine and patient-oriented research: improving health outcomes for individual patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13(1). https://doaj.org/article/a61e88786f384c77a54c0bd21723e11f. Accessed 23 Apr 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Fautrel B, Alten R, Kirkham B, de la Torre I, Durand F, Barry J, et al. Call for action: how to improve use of patient-reported outcomes to guide clinical decision making in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38(6):935–947. doi: 10.1007/s00296-018-4005-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alten R, Krüger K, Rellecke J, Schiffner-Rohe J, Behmer O, Schiffhorst G, et al. Examining patient preferences in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis using a discrete-choice approach. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2217–2228. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S117774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scalone L, Sarzi-Puttini P, Sinigaglia L, Montecucco C, Giacomelli R, Lapadula G, et al. Patients’, physicians’, nurses’, and pharmacists’ preferences on the characteristics of biologic agents used in the treatment of rheumatic diseases. Patient Prefer Adherence [Internet]. 2018;12:2153–2168. https://www.dovepress.com/patientsrsquo-physiciansrsquo-nursesrsquo-and-pharmacistsrsquo-prefere-peer-reviewed-article-PPA. Accessed 23 Apr 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Hifinger M, Hiligsmann M, Ramiro S, Watson V, Severens JL, Fautre B, et al. Economic considerations and patients’ preferences affect treatment selection for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a discrete choice experiment among European rheumatologists. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):126–132. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bolge SC, Goren A, Brown D, Ginsberg S, Allen I. Openness to and preference for attributes of biologic therapy prior to initiation among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: patient and rheumatologist perspectives and implications for decision making. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1079–1090. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S107790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hazlewood GS, Bombardier C, Tomlinson G, Thorne C, Bykerk VP, Thompson A, et al. Treatment preferences of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: a discrete-choice experiment. Rheumatol (United Kingdom) 2016;55(11):1959–1968. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matcham F, Scott IC, Rayner L, Hotopf M, Kingsley GH, Norton S, et al. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanderson T, Morris M, Calnan M, Richards P, Hewlett S. Patient perspective of measuring treatment efficacy: the rheumatoid arthritis patient priorities for pharmacologic interventions outcomes. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(5):647–656. doi: 10.1002/acr.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fraenkel L, Bogardus ST, Concato J, Felson DT, Wittink DR. Patient preferences for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(11):1372–1378. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.019422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Postmus D, Mavris M, Hillege HL, Salmonson T, Ryll B, Plate A, et al. Incorporating patient preferences into drug development and regulatory decision making: results from a quantitative pilot study with cancer patients, carers, and regulators. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99(5):548–554. doi: 10.1002/cpt.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—the pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med. 2012;368(1):6–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1209500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pablos JL, Jover JA, Roman-Ivorra JA, Inciarte-Mundo J, Dilla T, Sacristan JA, et al. Patient decision aid (PDA) for Patients with rheumatoid arthritis reduces decisional conflict and improves readiness for treatment decision making. Patient Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s40271-019-00381-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.