Mutants with abnormal LCIB localization reveal the importance of starch sheath formation for the CO2-concentrating mechanism in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii.

Abstract

Aquatic photosynthetic organisms induce a CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) to overcome the difficulty of acquiring inorganic carbon under CO2-limiting conditions. As part of the CCM, the CO2-fixing enzyme Rubisco is enriched in the pyrenoid located in the chloroplast, and, in many green algae, several thick starch plates surround the pyrenoid to form a starch sheath. In Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, low-CO2–inducible protein B (LCIB), which is an essential factor for the CCM, displays altered cellular localization in response to a decrease in environmental CO2 concentration, moving from dispersed throughout the chloroplast stroma to around the pyrenoid. However, the mechanism behind LCIB migration remains poorly understood. Here, we report the characteristics of an Isoamylase1-less mutant (4-D1), which shows aberrant LCIB localization and starch sheath formation. Under very-low-CO2 conditions, 4-D1 showed retarded growth, lower photosynthetic affinities against inorganic carbon, and a decreased accumulation level of the HCO3− transporter HLA3. The aberrant localization of LCIB was also observed in another starch-sheathless mutant sta11-1, but not in sta2-1, which possesses a thinned starch sheath. These results suggest that the starch sheath around the pyrenoid is required for the correct localization of LCIB and for the operation of CCM.

In the aquatic environment, photosynthetic activity is limited by the slow diffusion rate of CO2 and the low catalytic activity of the CO2-fixing enzyme ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), as well as energy loss due to the oxygenase activity of Rubisco. To maintain photosynthetic activity in such a CO2-deficient environment, most aquatic algae induce a CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) for the active uptake of inorganic carbon (Ci; CO2 and HCO3−) into cells and to concentrate CO2 into the pyrenoid, where Rubisco is enriched in the chloroplast (Badger et al., 1980). The pyrenoid is a central feature of the eukaryotic algal CCM (Meyer et al., 2017), which increases the CO2/O2 ratio at the active site of Rubisco, yielding maximum carboxylase activity. The physiological and molecular aspects of CCM in eukaryotic algae have been well studied in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Yamano and Fukuzawa, 2009; Mackinder, 2018). Recent studies revealed that the pyrenoid of Chlamydomonas is a liquid-like organelle, in which essential pyrenoid component 1 (EPYC1) interacts with Rubisco, bringing about a liquid–liquid phase separation (Mackinder et al., 2016; Freeman Rosenzweig et al., 2017; Wunder et al., 2018). Furthermore, proteomic studies and localization analysis have identified candidate proteins in the pyrenoid (Mackinder et al., 2017; Zhan et al., 2018). Cryo-electron microscopy revealed that thylakoid membranes penetrate the pyrenoid in the form of structures called pyrenoid tubules (Engel et al., 2015). Within the pyrenoid tubules, several minitubules connect the chloroplast stroma to the pyrenoid matrix, possibly to facilitate the rapid diffusion of small molecules such as ATP and metabolites from the Calvin–Benson cycle.

Several starch plates composed of multiple starch granules surround the pyrenoid, forming a prominent ring-like starch sheath (Sager and Palade, 1957). The starch sheath rapidly forms in response to a decrease in environmental CO2 concentration (Kuchitsu et al., 1988). Because the timing of starch sheath formation coincides with the induction of the CCM (Ramazanov et al., 1994), it has been proposed that the starch sheath acts as a barrier to prevent CO2 diffusion from the pyrenoid. On the other hand, other studies have suggested that absence of the starch sheath does not affect the photosynthetic ability of the cells, indicating that the starch sheath itself is not directly involved in the CCM (Villarejo et al., 1996). Recently, starch granules abnormal 1 (SAGA1) was identified as a protein that physically interacts with Rubisco in the starch plates (Itakura et al., 2019). A saga1 mutant showed abnormal starch plates and multiple pyrenoids without the pyrenoid tubule network.

Another essential factor for the CCM is the active Ci transport system that concentrates extracellular Ci into the pyrenoid. It was reported that Chlamydomonas acclimates to two distinct limiting CO2 conditions, termed low-CO2 (LC; ∼0.03% to 0.5% CO2 in growth-chamber culture or 7–70 μm CO2 in liquid culture) and very-low–CO2 (VLC; <0.02% CO2 or <7 μm CO2), and that there are at least two types of Ci transport systems dependent on external CO2 concentrations (Wang and Spalding, 2014a).

Under VLC conditions, HCO3− is actively transported from outside of the cell to the chloroplast stroma by the cooperative function of high-light activated 3 (HLA3) located in the plasma membrane and low-CO2–inducible protein A (LCIA) in the chloroplast envelope (Miura et al., 2004; Duanmu et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2015; Yamano et al., 2015). Additionally, three bestrophin-like proteins located in the thylakoid membrane may be associated with HCO3− transport from the chloroplast stroma to the thylakoid lumen (Mukherjee et al., 2019). Upon entering the lumen, HCO3− in the lumen is converted to CO2 by α-type carbonic anhydrase in the pyrenoid tubules, to be fixed by Rubisco (Karlsson et al., 1998).

Under LC conditions, Ci transport switches from the HLA3/LCIA-dependent HCO3− uptake system to a CO2 uptake system involving low-CO2–inducible protein B (LCIB; Miura et al., 2004; Wang and Spalding, 2014a). LCIB accumulates slightly under high-CO2 (HC) conditions during aeration with air containing 5% CO2, but is strongly accumulated during CCM induction under LC and VLC conditions (Yamano et al., 2010). LCIB interacts with its homologous protein LCIC (Yamano et al., 2010); the crystalline structure of these proteins resembles β-type carbonic anhydrase and has an active site of carbonic anhydrase that coordinates with a zinc ion (Jin et al., 2016). Based on these findings, the LCIB/LCIC complex is assumed to convert CO2 to HCO3− to maintain the Ci pool in the stroma. An lcib mutant cannot grow under LC conditions but can survive under VLC conditions (Wang and Spalding, 2006; Yamano et al., 2010). This unique phenotype is supported by the biphasic phenotype of photosynthetic O2-evolving activity. Below 7 µm CO2, the O2-evolving activity of the lcib mutant is comparable to that of wild-type cells, but it decreases under 7–70 µm CO2 (Yamano et al., 2010; Wang and Spalding, 2014a), suggesting that LCIB is indispensable, particularly under LC conditions. Furthermore, the lcia/lcib double mutant showed a slower growth rate than the lcia single mutant, indicating that LCIB is also required for the CCM under VLC conditions (Wang and Spalding, 2014a).

LCIB changes its localization within the chloroplast in response to CO2 concentrations. Under HC and LC conditions, LCIB disperses within the chloroplast stroma and maintains the intracellular Ci accumulation by rapid conversion of CO2, which is passively transported from outside the cells, to HCO3− (Wang and Spalding, 2014a). Under VLC conditions, LCIB is known to form puncta around the starch sheath’s periphery (Yamano et al., 2010; Wang and Spalding, 2014b). Previously, the CO2-dependent migration patterns of LCIB were suggested to contribute to the CCM (Yamano et al., 2014).

Here, through analysis of a newly isolated mutant with aberrant LCIB localization under VLC conditions, we present evidence to support the importance of the starch sheath around the pyrenoid for proper LCIB localization and operation of the CCM under CO2-limiting stress conditions.

RESULTS

Screening of Mutants with Aberrant LCIB Localization

To identify new factors responsible for LCIB migration to the pyrenoid in response to changes in CO2 concentration, we first generated a Chlamydomonas marker strain, AN-1, expressing functional LCIB fused with fluorescent protein Clover in an lcib-mutant background. This AN-1 strain was generated by transformation of the lcib-insertion mutant LMJ.RY0402.173287, hereafter designated as “B1” (Supplemental Table S1), from the CLiP Library (Li et al., 2016) with a LCIB-Clover expression plasmid (pCT1) driven by a constitutive HSP70A-RBCS2 (AR) promoter (Nitta et al., 2018). In lcib-mutant B1, the aphVIII cassette was inserted in the sixth exon of LCIB with a 1-bp deletion (Supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). Due to this disruption of LCIB, its interaction partner LCIC was hardly detected in B1, as shown in Yamano et al. (2010; Supplemental Fig. S1C). Additionally, the accumulation levels of LCIA and HLA3 also decreased in B1.

To examine whether LCIB-Clover in AN-1 was functional in vivo, we compared the growth rates of wild-type strain CC-5325, B1, and AN-1 under different CO2 conditions and evaluated their photosynthetic characteristics by measuring the rates of Ci-dependent O2-evolution. Although B1 cells grew slowly under LC conditions as well as under VLC conditions (Supplemental Fig. S1D), AN-1 cells grew similarly to CC-5325 under all conditions tested. The Ci concentration required for half-maximal O2-evolving activity (K0.5 [Ci]) for AN-1 (24 ± 5 µm) was significantly lower than that in B1 (1,225 ± 91 μm) and at the same level as that in CC-5325 (28 ± 3 µm; Supplemental Fig. S1E and Supplemental Table S2). Furthermore, the accumulation of HLA3 and LCIA as well as LCIC were recovered in AN-1 cells by the introduction of pCT1 (Supplemental Fig. S1C). Because AN-1 cells expressed CCM at a comparable level to wild-type cells, we used AN-1 as a marker strain for the subsequent screening of mutants with aberrant LCIB localization.

We generated 2,400 spectinomycin-resistant transformants by random insertion of the aadA cassette into AN-1. By observing fluorescent signals derived from LCIB-Clover, we isolated four mutants (4-D1, 16-F5, 21-A5, and 22-B8) showing dispersed localization of LCIB-Clover in the chloroplast even under VLC conditions (Supplemental Fig. S2). Among these, we selected 4-D1 alone for further analyses, because 4-D1 almost lost its starch sheath, as described below.

Isoamylase1 Is the Causal Gene for the 4-D1 Mutant Phenotype

To identify the gene responsible for the mutation in 4-D1, we determined the nucleotide sequences of the flanking regions of the inserted aadA cassette by thermal asymmetric interlaced (TAIL)-PCR. Using aadA cassette-specific downstream primer (DP), the sequence derived from the 13th intron of Cre03.g155001 corresponding to Isoamylase1 (ISA1) was amplified (Fig. 1A), indicating that ISA1 was disrupted in 4-D1 (Fig. 1B). Because DNA amplification using the aadA-specific upstream primer and the 14th intron-specific primer R6 failed, some DNA rearrangements may have occurred in the boundary region between the aadA cassette and the 14th intron.

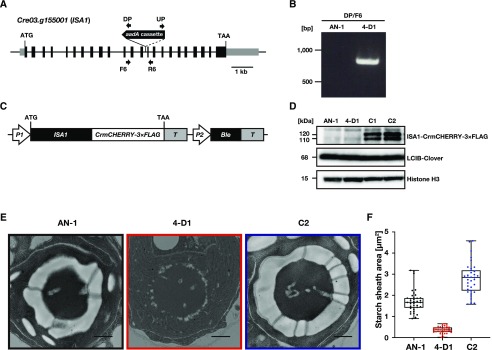

Figure 1.

Characterization of the 4-D1 mutant and its complemented strains. A, Schematic of aadA cassette insertion into ISA1 in 4-D1. Exons, introns, and untranslated regions are shown as black boxes, black lines, and gray boxes, respectively. Locations for PCR primers are indicated by arrows. DP, downstream primer; UP, upstream primer. B, Genomic PCR to confirm insertion of the aadA cassette in 4-D1. AN-1 was used as a negative control. C, Schematic of the expression plasmid for complementation. P1, HSP70A/RBCS2 tandem promoter; T, 3′-untranslated region of RBCS2; P2, RBCS2 promoter. Ble resistance to Zeocin was used as a selection marker. D, Accumulation of ISA1-CrmCHERRY-3×FLAG and LCIB-Clover fusion proteins in AN-1, 4-D1, C1, and C2. Cells grown in 5% (v/v) CO2 were shifted to 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for 24 h. Histone H3 was used as a loading control. E, Representative TEM images of AN-1, 4-D1, and C2. Cells grown in 5% (v/v) CO2 were shifted to 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for 24 h. Scale bars = 1 μm. F, Starch sheath areas calculated using TEM images. Median values derived from the analysis of AN-1, 4-D1, and C2 are represented with error bars depicting the interquartile range (n = 35–37).

A previous study showed that ISA1 is the gene disrupted in the starchless mutant sta7, and that the gene product, as a starch-debranching enzyme, is essential for starch synthesis (Mouille et al., 1996). To determine whether the phenotype of 4-D1 could be complemented by expression of the normal ISA1 protein, we introduced an expression plasmid pTMZ1-ISA1, in which ISA1 was fused with CrmCHERRY and 3×FLAG tag driven by an AR promoter using Ble as a selection marker (Fig. 1C) into 4-D1. By immunoblotting analysis of Zeocin-resistant transformants using an anti-FLAG antibody, we isolated two strains, C1 and C2, which accumulated proteins of ∼110 and 120 kD (Fig. 1D). Considering that two amino acid sequences of ISA1 with different length were deposited in GenBank (96.3 kD; AY324649) and Phytozome (115.7 kD; Cre03.g155001), respectively, the two bands detected in the immunoblotting analysis could be derived from splice variants of ISA1 mRNA. Alternatively, we could not exclude other possible posttranslational modifications of ISA1, such as processing, phosphorylation, or glycosylation.

Next, to check the restoration of starch synthesis activities of C1 and C2, we estimated the accumulated levels of starch by iodine staining, measured the starch content, and quantified the starch area using electron micrographs. In AN-1, C1, and C2, the color of extracted cells turned dark purple with iodine treatment (Supplemental Fig. S3) with 10.2, 9.2, and 9.1 μg mm−3 starch content, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S4). Consequently, the starch sheath surrounding the pyrenoid was observed in bright field images of AN-1, C1, and C2 (Supplemental Fig. S3) as well as in images of AN-1 and C2 obtained using transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Fig. 1E; Supplemental Fig. S5). By contrast, 4-D1 cells were light yellow in the presence of iodine with starch content of only 0.8 μg mm−3. In TEM images of 4-D1, no clear starch plates were observed, but low-electron-density structures, corresponding to possible small starch granules, were detected around the pyrenoid. The median values of the total starch area in the vicinity of the pyrenoid in TEM images decreased significantly to 0.37 µm2 in 4-D1 compared with 1.67 μm2 in AN-1 and 2.85 μm2 in C2 (Fig. 1F).

CO2-dependent LCIB Localization Is Aberrant in ISA1-less Mutant

To examine LCIB localization patterns in response to changes of CO2 concentration in AN-1, 4-D1, and C2, we observed intracellular fluorescent signals derived from LCIB-Clover along with measurement of the CO2 concentrations in the culture medium (Fig. 2A). From the obtained images, we quantified LCIB migration patterns by calculating the coefficient of variation (CV) values of the LCIB-Clover fluorescent signals (Fig. 2B). High- and low-CV values indicated aggregated and dispersed patterns, respectively, of the fluorescent signals inside of the cell (Nitta et al., 2018).

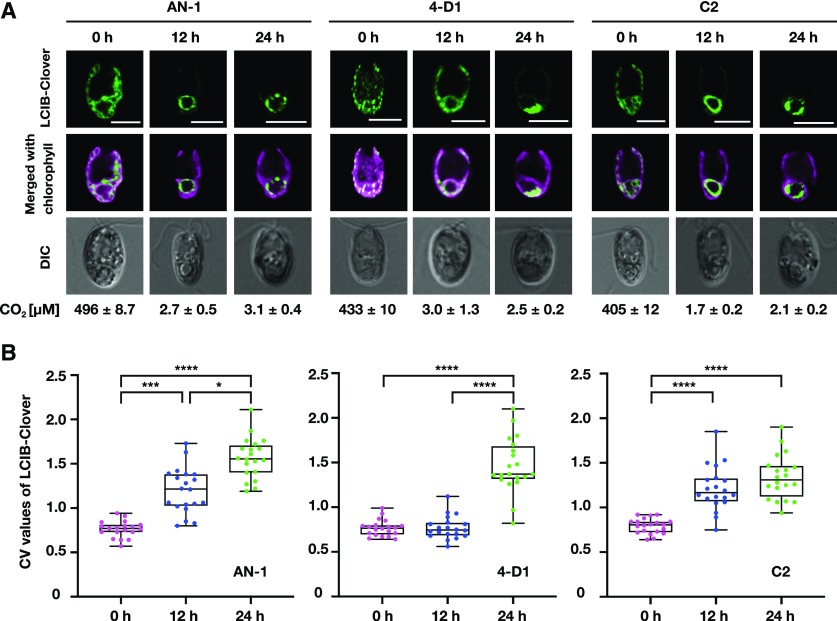

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization of LCIB in the 4-D1 mutant and its complemented strain. A, Representative LCIB-Clover fluorescence images of AN-1, 4-D1, and C2. Cells grown in 5% (v/v) CO2 (0 h) were shifted to 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for 12 h or 24 h. CO2 concentrations calculated from the total Ci concentration in the culture medium are shown below each image. DIC, differential image contrast. Scale bars = 5 μm. B, Quantification of localization patterns of LCIB-Clover. The CV value of the fluorescence intensity was calculated in each cell to quantify LCIB-Clover localization. The median values derived from the analysis of AN-1, 4-D1, and C2 cells are represented with error bars depicting the interquartile range (n = 19–20). Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test was used to assess the statistical significance of LCIB-Clover localization between different conditions (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001).

Under HC conditions, LCIB-Clover fluorescent signals in AN-1 (median CV value 0.77), 4-D1 (0.76), and C2 (0.81) were dispersed in the chloroplast. After replacing the culture medium and aerating with air containing 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for 12 h, the CO2 concentrations in the culture medium decreased to the range of 1.7–3.0 µm in all strains corresponding to VLC conditions (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. S6). LCIB-Clover in AN-1 (median CV value 1.22 at 12 h) and C2 (1.16 at 12 h) associated with the ring-like structure around the pyrenoid, whereas fluorescent signals of LCIB-Clover in 4-D1 (0.75 at 12 h) remained dispersed in the chloroplast. After 24 h, CO2 concentrations were 2.1–3.1 µm, in which VLC conditions were maintained. Signals of LCIB-Clover in 4-D1 (1.37 at 24 h) were associated with the basal region of the chloroplast, in contrast to the ring-like structure around the pyrenoid observed in AN-1 (1.55 at 24 h) and C2 (1.31 at 24 h). These results suggest that migration and the ring-like-organization of LCIB around the pyrenoid under VLC conditions requires starch sheath formation.

Starch Sheath Formation Is Required for LCIB Localization under VLC Conditions

To further verify the contribution of starch sheath formation to LCIB localization under VLC conditions, we compared LCIB localization patterns between the two starchless mutants sta11-1 and sta2-1. sta11-1 is defective in α-1,4 glucanotransferases, whereas sta2-1 is defective in a granule-bound starch synthase I (Delrue et al., 1992; Colleoni et al., 1999).

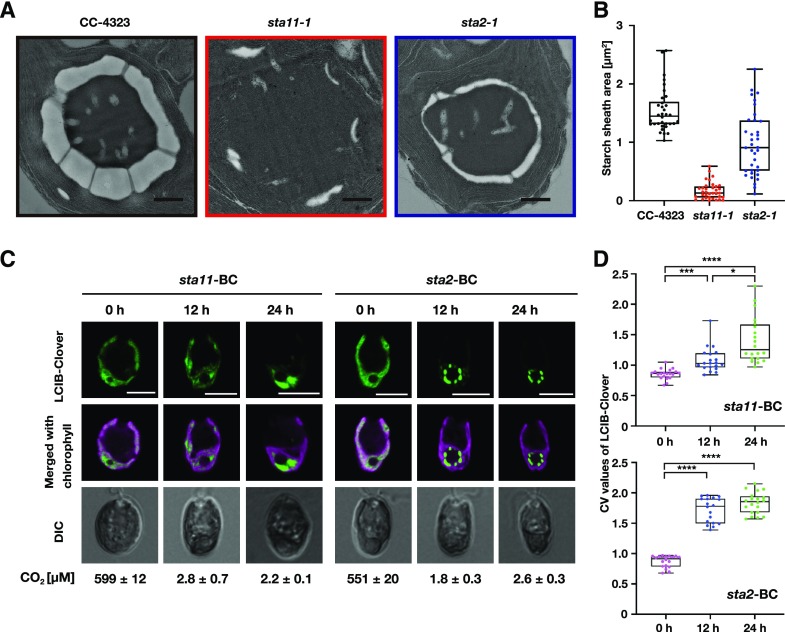

First, we observed sta11-1, sta2-1, and their parental strain CC-4323 using TEM (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. S5). sta11-1 cells possessed small starch-plate-like structures surrounding the pyrenoid with irregular orientation, and no prominent starch sheath formation. In sta2-1 cells, the starch sheath surrounding the pyrenoid was observed, but the starch plates were thinner than those in CC-4323. The median values of the total starch area in the vicinity of the pyrenoid decreased significantly to 0.13 µm2 in sta11-1 and 0.91 µm2 in sta2-1 compared with 1.45 µm2 in CC-4323 (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Starch sheath formation is required for the localization of LCIB around the pyrenoid. A, Representative TEM images of CC-4323, sta11-1, and sta2-1. Cells were grown in 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for 24 h. Scale bars = 1 μm. B, Starch sheath areas calculated using TEM images. The median values derived from the analysis of CC-4323, sta11-1, and sta2-1 cells are represented with error bars depicting the interquartile range (n = 34–36). C, Representative LCIB-Clover fluorescence images of sta11-BC and sta2-BC. Cells grown autotrophically in 5% (v/v) CO2 (0 h) were shifted to 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for 12 or 24 h. CO2 concentrations shown below the images were calculated from the total Ci concentration in the culture medium measured at the time of observation of LCIB localization. DIC, differential image contrast. Scale bars = 5 μm. D, Quantification of the localization patterns of LCIB-Clover. The CV value of the fluorescence intensity was calculated in each cell to quantify LCIB-Clover localization. The median values derived from the analysis of sta11-BC and sta2-BC cells are represented with error bars depicting the interquartile range (n = 18–20). Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test was used to assess the statistical significance of LCIB-Clover localization between different conditions (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.00, and ****P < 0.0001).

To examine the localization pattern of LCIB, we introduced an expression plasmid, pCT1, into sta11-1 and sta2-1 mutants, and transformants exhibiting fluorescent signals were designated as sta11-BC and sta2-BC. After iodine staining, the color of sta11-BC cells remained light yellow (Supplemental Fig. S7), and the starch content was barely detectable (Supplemental Fig. S4). By contrast, iodine-stained sta2-BC cells turned reddish brown due to the accumulation of structurally modified amylopectin. The total starch content in sta2-BC cells was reduced to 7.1 μg mm−3 from 10.2 μg mm−3 in AN-1 (Supplemental Fig. S4).

Under HC conditions, LCIB-Clover fluorescent signals in sta11-BC (median CV value 0.86) and sta2-BC (0.91) were dispersed in the chloroplast (Fig. 3, C and D; Supplemental Fig. S6). After replacing the culture medium and aerating with air containing 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for 12 h, the migration process of LCIB-Clover to the pyrenoid was retarded in sta11-BC cells (1.03 at 12 h), similar to 4-D1, compared with that of sta2-BC (1.78 at 12 h) even when CO2 concentration was in the range of VLC conditions (1.8–2.8 µm CO2). After 24 h, LCIB-Clover aggregated at the basal region of the chloroplast in sta11-BC (1.26 at 24 h), but did not show a ring-like structure around the pyrenoid as shown in sta2-BC (1.86 at 24 h). These results suggest that when multiple starch plates surround the pyrenoid, LCIB localizes around the starch sheath under VLC conditions irrespective of the thickness or composition of the starch plates.

Growth Is Retarded in 4-D1 and sta11, But Not in sta2, under VLC Conditions

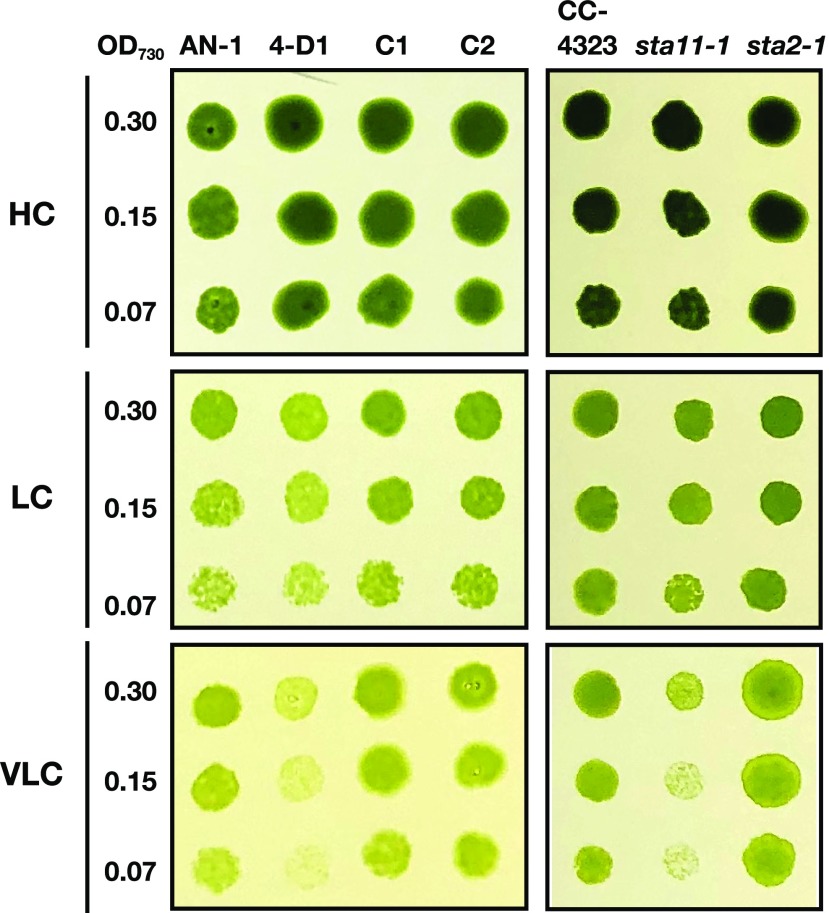

To examine the physiological importance of starch sheath formation in CCM, we compared the growth of 4-D1, sta11-1, and sta2-1 with that of the respective parental strains under different CO2 conditions supplied with air containing 5% CO2 (HC), 0.04% CO2 (LC), or 0.01% CO2 (VLC; Fig. 4). Although there were no significant differences under HC conditions, growth of 4-D1 and sta11-1 were retarded compared to that in AN-1 and CC-4323, respectively, under VLC conditions. By contrast, sta2-1 grew normally under VLC as well as LC conditions.

Figure 4.

Spot tests for the growth of starch mutants. Cells were diluted to the indicated optical density (OD), and 3 μL of each cell suspension was spotted onto MOPS-P agar plates, and incubated under HC (5% [v/v] CO2) or LC (0.04% [v/v] CO2) conditions for 4 d, or VLC (0.01% [v/v] CO2) conditions for 5 d.

Photosynthetic Ci Affinity Is Decreased in Starch Sheath Mutants

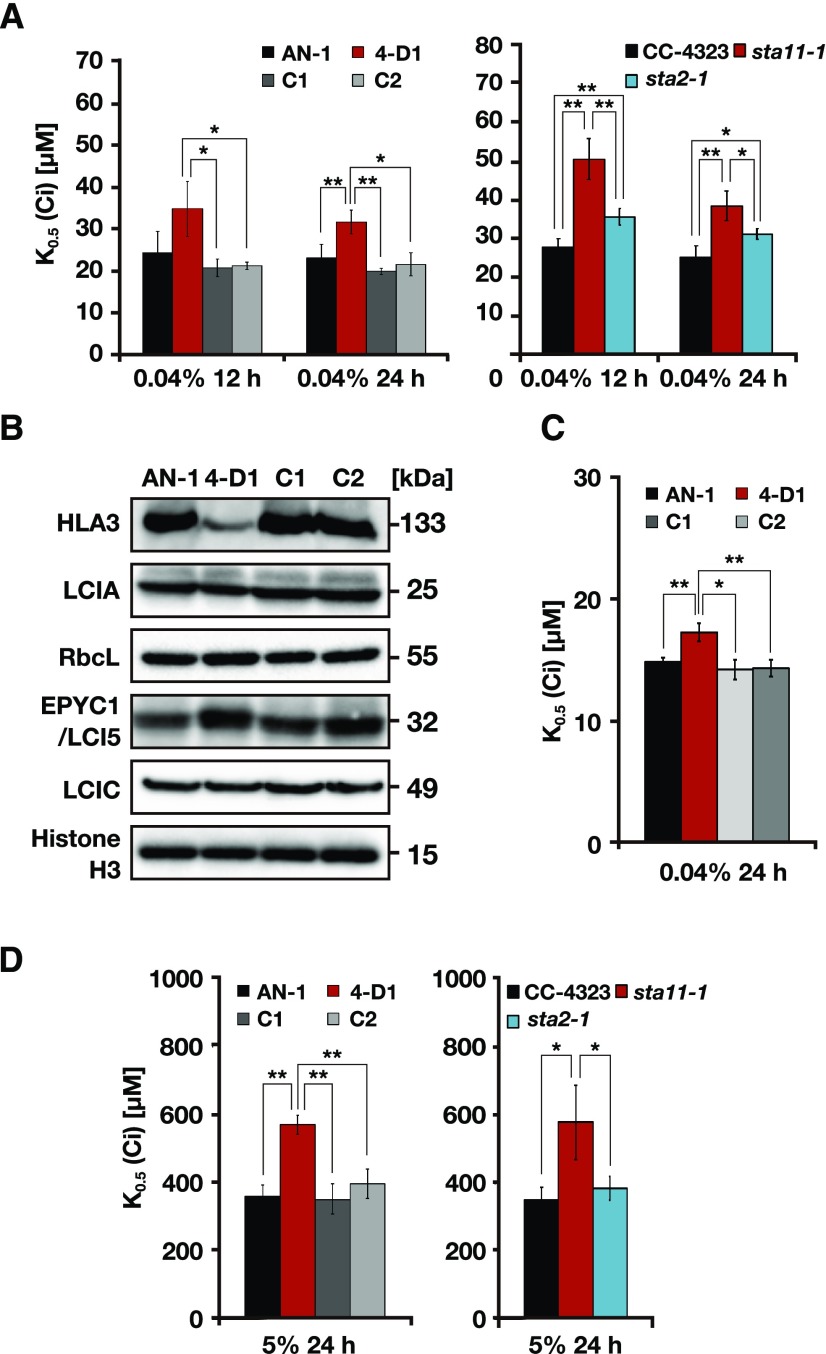

The retarded growth of 4-D1 and sta11-1 mutants under VLC conditions indicates that the starch sheath may contribute to the CCM. To clarify this hypothesis, we measured the O2-evolving activity of 4-D1, sta11-1, and sta2-1 (Fig. 5A; Supplemental Table S2). When aerating with air containing 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for 12 h or 24 h, the K0.5 (Ci) values of 4-D1 cells (35 ± 7 μm at 12 h and 32 ± 3 μm at 24 h) were 1.4–1.7-fold higher than those of AN-1 (24 ± 5 μm at 12 h and 23 ± 3 μm at 24 h), C1 (21 ± 2 μm at 12 h and 20 ± 1 μm at 24 h), and C2 (21 ± 1 μm at 12 h and 22 ± 3 μm at 24 h). The maximum rates of O2-evolving activity (Vmax) were comparable in each strain (Supplemental Table S2). Similarly, the K0.5 (Ci) values of sta11-1 (51 ± 5 μm at 12 h and 39 ± 4 μm at 24 h) were 1.5–1.8-fold higher than that of CC-4323 (28 ± 2 μm at 12 h and 25 ± 3 μm at 24 h). This decrease of Ci affinity was alleviated in sta2-1 (36 ± 2 μm at 12 h and 31 ± 1 μm at 24 h), in which the K0.5 (Ci) values were 1.2–1.3-fold higher than that of CC-4323 (Fig. 5A; Supplemental Table S2). These results suggest that a starch sheath with thick starch plates, as well as ring-like LCIB localization around the starch sheath, is required for maintaining photosynthetic Ci affinity.

Figure 5.

Physiological characteristics of starch mutants. A, Ci affinity of the indicated strains at pH 7.8. Cells grown in 5% (v/v) CO2 were shifted to 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for 12 or 24 h. Photosynthetic O2-evolving activity was measured in external dissolved Ci concentrations at pH 7.8, and the K0.5 (Ci) value—the Ci concentration required for half-maximal rate—was calculated. Data in all experiments are mean values ± sd from three or four biological replicates. B, Accumulation of CCM-related proteins in AN-1, 4-D1, C1, and C2. Cells grown in 5% (v/v) CO2 were shifted to 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for 12 h. Histone H3 was used as a loading control. C, Ci affinity of the indicated strains at pH 6.2. Cells grown in 5% (v/v) CO2 were shifted to 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for 24 h. D, Ci affinity of the indicated strains at pH 7.8. Cells were grown in 5% (v/v) CO2 for 24 h. A, C, and D, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by Student’s t test.

To explore the possible cause of decreased Ci affinity in 4-D1, we examined the accumulation levels of CCM-related proteins. The accumulation levels of LCIA, Rubisco large subunit (RbcL), EPYC1/LCI5, and LCIC were comparable in all strains (Fig. 5B). By contrast, the accumulation level of HLA3 was reduced in 4-D1, but recovered in C1 and C2. Furthermore, to distinguish whether reduced HLA3 accumulation itself caused the decreased Ci affinity in 4-D1, we measured O2-evolving activity at pH 6.2, where the contribution of HLA3 could be ignored (Yamano et al., 2015). The decreased Ci affinity was alleviated at pH 6.2, but the K0.5 (Ci) values of 4-D1 (17 ± 1 μm at 24 h) were still 1.2-fold higher than that in AN-1 (15 ± 1 μm at 24 h), C1 (14 ± 1 μm at 24 h), and C2 (14 ± 1 μm at 24 h; Fig. 5C; Supplemental Table S3). Similarly, the K0.5 (Ci) values of 4-D1 (571 ± 29 μm) were 1.4–1.6-fold higher than that in AN-1 (361 ± 33 μm), C1 (352 ± 45 μm), and C2 (398 ± 43 μm) and that of sta11-1 (579 ± 109 μm) was also 1.7-fold higher than that in CC-4323 (384 ± 34 μm), even under HC conditions (Fig. 5D), in which HLA3 did not accumulate, LCIB was dispersed throughout the chloroplast, and CCM was suppressed.

DISCUSSION

The Starch Sheath Is Required for the CCM

In this study, we elucidated the contribution of the starch sheath to the CCM by characterizing mutants with aberrant LCIB localization. A previous study proposed that starch sheath formation itself is not involved in the CCM, because the isa1 allelic mutant BAFJ-6, in which no starch sheath formed, did not show a significant decrease in Ci affinity compared with cw-15 cells (Villarejo et al., 1996). However, a small difference in O2-evolving activity could be overlooked in this report because the phenotype of BAFJ-6 cells was not compared with its parental strain CC-125, and the phenotype of the complemented strain was not examined. On the other hand, another study reported that the isa1 allelic mutant sta7-10 showed slightly lower rates of photosynthetic O2 evolution compared with the parental strain CC-425 (Posewitz et al., 2004), but the detailed characteristics of the CCM were not examined. In this study, through various verifications using several starch mutants, parental strains, and complemented strains, we conclude that the starch sheath itself is required for LCIB localization around the starch sheath as well as maintaining an increased Ci affinity under VLC conditions.

Ci affinity in 4-D1 and sta11-1 decreased under HC as well as VLC conditions (Fig. 5D). Similarly, saga1 cells with abnormal starch sheath morphology showed a decreased photosynthetic rate at saturating concentrations of Ci when acclimated to both HC and LC conditions (Itakura et al., 2019). The observations that the CCM is slightly induced even under HC conditions (Badger et al., 1980) and that a starch-sheath–like structure was observed in TEM images of cells grown under HC conditions (Mackinder et al., 2016), suggest the possibility that starch synthesis and/or starch sheath formation may be necessary to increase CO2 availability for Rubisco under HC as well as CO2-limiting conditions.

The physical barrier role of the starch sheath itself with thick starch plates may not only limit CO2 diffusion out of the pyrenoid but also help shield the pyrenoid matrix from photosynthetically evolved O2 in the chloroplast stroma. This is possibly analogous to the O2-evolving PSII being excluded from the pyrenoid tubules in green algae (McKay and Gibbs, 1991). Thus, starch sheath formation may contribute to the spatial separation between the sites of O2 evolution and CO2 fixation to maintain Rubisco carboxylation activity and to avoid Rubisco oxygenation leading to the energetically expensive process of photorespiration.

Another phenotype of 4-D1 is a decreased accumulation level of HLA3 alongside normal accumulation of LCIA (Fig. 5B). In the absence of a starch sheath, the intracellular CO2 flux may change, which may influence the expression or accumulation of CCM-related factors. A comprehensive analysis of gene expression changes by RNA sequencing in starch-sheathless mutants could reveal the relationship between the starch sheath and expression of CCM components.

Relationship between Starch Sheath Formation and LCIB Localization

How does the starch sheath contribute to normal LCIB localization under VLC conditions? One possibility is that the starch sheath surrounding the pyrenoid acts as a scaffold for LCIB localization. Thus, the absence of a starch sheath prevents LCIB localization from forming a ring-like structure around the starch sheath; accordingly, LCIB aggregates at the basal region of the chloroplast. Because LCIB and LCIC do not have a starch-binding domain and exist as soluble proteins in the chloroplast stroma (Yamano et al., 2010), it is unlikely that the LCIB/LCIC complex binds directly to the starch sheath. Alternatively, the LCIB/LCIC complex may be positioned to the outside of the starch sheath via an unidentified linker protein.

SAGA1 containing a carbohydrate-binding module (CBM), CBM20 could localize to the inner side of the starch sheath to restrict starch granule elongation at the end of the starch plate, thereby forming a thick starch sheath (Itakura et al., 2019). Similarly, LCIB could be located outside the starch sheath via an unknown factor containing a starch-binding domain. For example, starch branching enzyme 3 with CBM48 and low-CO2-inducible protein 9 with CBM20 localize around the pyrenoid (Mackinder et al., 2017); these proteins could play a role as a linker between LCIB and the starch sheath. Additionally, ISA1 also contains CBM48, and was detected in the purified pyrenoid in the proteomic study (Zhan et al., 2018). Considering the size-exclusion (∼80 kD) effect of the pyrenoid due to the characteristic of its liquid–liquid phase separation (Mackinder et al., 2017), ISA1 at 91 kD could be excluded from localizing in the pyrenoid matrix. Although we could not detect fluorescent signals derived from ISA1-CrmCHERRY-3×FLAG, it will be necessary to analyze ISA1 localization by alternative methods to examine the relationship with LCIB localization.

A recent study showed that bestrophin-like proteins localized on the thylakoid membrane are enriched ∼1.5-fold around the pyrenoid relative to the rest of the chloroplast (Mukherjee et al., 2019). Considering that bestrophin-like proteins could interact with LCIB (Mackinder et al., 2017), a model for the CO2-recapture system around the pyrenoid was proposed in cooperation with a bestrophin-like protein and the LCIB/LCIC complex (Mukherjee et al., 2019). Previous immunogold electron microscopy using an anti-LCIB antibody suggested that LCIB may be enriched in the vicinity of a gap in the starch sheath (Yamano et al., 2010), where CO2 can readily diffuse from the pyrenoid matrix. Therefore, a starch-sheathless mutant may not efficiently maintain the Ci pool in the vicinity of the pyrenoid owing to a defect in the CO2-diffusing barrier of the starch sheath and also to an inefficient CO2-recapture system due to the aggregation of LCIB at the basal region of the chloroplast.

Mechanism of LCIB Migration toward the Pyrenoid

Although this study revealed that the starch sheath is required for proper LCIB localization around the pyrenoid, the mechanism of LCIB migration to the pyrenoid in response to a decrease in CO2 concentration remains unclear. Because dispersed LCIB-Clover was able to migrate toward the bottom of the chloroplast even in sheathless mutants, LCIB can respond to changes in CO2 concentration regardless of starch sheath formation. Considering that Ci concentrations could increase in the vicinity of pyrenoid due to maintenance of the Ci pool during CCM operation, it might be possible that LCIB itself and/or LCIB-interacting proteins including LCIC migrate toward cellular locations with higher levels of Ci concentrations. When the starch sheath is missing, the efficiency of maintaining Ci pools in the vicinity of the pyrenoid may reduce due to the leakage of CO2 from the pyrenoid. This situation could result in a delay in forming a gradient of Ci concentration in the chloroplast, causing a delay in LCIB migration toward the pyrenoid, as shown in the 4-D1 and sta11-1 mutants.

We present here a reappraisal of the contribution of the starch sheath to the CCM using a forward genetics approach. This means that mutant screening is still important to identify novel CCM components and its regulation. Previously, we succeeded in ultra-fast screening of mutants with aberrant LCIB localization based on real-time calculation of CV values of LCIB-Clover using intelligent image-activated cell sorting (Nitta et al., 2018). This technology enabled us to screen mutants showing dispersed localization under VLC conditions from over 220,000 transformants. From massive mutant screening techniques such as intelligent image-activated cell sorting, further components of CCM operation and its regulation may be revealed to enhance our molecular understanding of the CCM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture and Growth Conditions

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strain CC-5325 and mutants lcib, sta11-1, and sta2-1 were obtained from the Chlamydomonas resource center. For physiological and biochemical experiments, 5 mL of cells were precultured in Tris-acetate-phosphate medium by vigorous shaking, and diluted with MOPS-P medium, which contained phosphate (620 mm of K2HPO4 and 412 mm of KH2PO4) and Hutner’s trace elements supplemented with 20 mm of MOPS. The cells were cultured by aerating with air containing 5% (v/v) CO2 (HC) until midlog phase. HC-acclimated cells were centrifuged at 600g, resuspended in 50 mL of fresh MOPS-P medium, and cultured by aerating with air containing 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for the indicated time periods. Cells were cultured at 25°C with continuous illumination at 120 μmol photons m−2 s−1 unless otherwise indicated. The genotypes of strains used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Mutant Screening

A DNA cassette containing an aadA gene was amplified using PrimeSTAR GXL DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio) with pALM32 (Meslet-Cladière and Vallon, 2011) as a template and aadA-ATG-less-F/pHyg-R2 primer set. The PCR product was purified using a PCR purification kit (QIAGEN) and the concentration was adjusted to 100 ng μL−1. The aadA cassette was used to transform AN-1 cells by electroporation using a NEPA-21 electroporator (NEPAGENE), as described in Yamano et al. (2013). Spectinomycin-resistant transformants were grown in 200 μL of MOPS-P medium using 96-well microtiter plates in a chamber supplied with 5% (v/v) CO2 for 24 h, and then shifted in a chamber supplied with 0.04% (v/v) CO2 for CCM induction. Mutants showing aberrant LCIB localization were obtained by observation of LCIB-Clover fluorescent signals in each transformant using an Axioskop 2 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss). Sequences of the primers used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S4.

TAIL-PCR

TAIL-PCR was performed as described in Wang et al. (2014). To amplify the downstream flanking region of the inserted aadA cassette, specific primers DP-1 and DP-2 were used for primary and secondary PCR reactions, respectively. We also used degenerate primers A3, A5, and A6 as random primers (Liu et al., 1995; Liu and Whittier 1995).

Complementation of the 4-D1 Mutant

To generate the ISA1-CrmCHERRY-3×FLAG expression plasmid (pTMZ1-ISA1), the following cloning steps were performed. First, to remove the aphVIII coding region from pMO520 (Onishi and Pringle, 2016), inverse PCR was carried out using PrimeSTAR Max DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio) and aphVIII-deletion-F1/aphVIII-deletion-R1 primer set, resulting in pMO520-aphVIII-del. Next, the coding sequence of Ble was amplified using PrimeSTAR GXL with the pSP124S plasmid (Lumbreras et al., 1998) as a template and ble-fusion-F1/ble-fusion-R1 primer set. Then, the PCR product was purified and cloned into pMO520-aphVIII-del digested with PciI using the SLiCE cloning method (Motohashi, 2015), resulting in plasmid pTMZ1. Next, the genomic sequence of ISA1 was amplified with KOD FX Neo (TOYOBO) using a custom-made fosmid clone (009-B12) as a template and ISA1-fusion-F1/ISA1-fusion-R2 primer set. Finally, the PCR product of the ISA1 fragment was inserted into the pTMZ1 digested with HpaI using SLiCE to obtain pTMZ1-ISA1, which was used to transform 4-D1 cells by electroporation using a NEPA-21 electroporator, as described in Yamano et al. (2013). The transformants were isolated on Tris-acetate-phosphate plates containing 10 μg of mL−1 zeocin.

Spot Test Analysis

Cultured cells at midlog phase were diluted with MOPS-P medium to OD730 of 0.30, 0.15, and 0.07, and 3 μL of each cell suspension was spotted onto MOPS-P agar plates. The plates were kept in air growth chambers under HC (5% [v/v] CO2), LC (0.04% [v/v] CO2), or VLC (0.01% [v/v] CO2) conditions for 3–5 d.

Immunoblotting Analysis

Immunoblotting analyses to detect soluble proteins (LCIB, LCIC, LCI5/EPYC1, RbcL, ISA1-CrmCHERRY-3×FLAG, and Histone H3) and membrane-bound proteins (HLA3 and LCIA) were performed as described in Yamano et al. (2010) and Wang et al. (2016). The primary antibodies were used at the indicated dilutions: rabbit anti-LCIB (1:5,000 dilution), rabbit anti-LCIC (1:10,000), rabbit anti-LCIA (1:5,000), rabbit anti-HLA3 (1:1,000), rabbit anti-Histone H3 (1:20,000), mouse anti-FLAG (1:10,000), rabbit anti-RbcL (1:10,000), and chicken anti-LCI5 (1:2,000). To recognize the primary antibody, a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Life Technologies) or goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Life Technologies) was used as a secondary antibody in a dilution of 1:10,000, or goat anti-chicken IgY-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a dilution of 1:5,000.

Starch Detection by Iodine Staining and Quantitative Analysis

Starch was assayed using iodine staining as described in Posewitz et al. (2004) with slight modifications. Briefly, cultured cells at OD730 of 0.6–1.0 were centrifuged, the pellets were mixed with 5 mL of 95% (v/v) ethanol, and vortexed vigorously. The resuspended cells were centrifuged at 22,100g, the pellet was resuspended in 3 mL of water, and autoclaved at 121°C for 1 min to solubilize starch. After autoclaving, the resuspended sample was cooled on ice, and 10 µL of iodine solution (0.05 m; Wako) was added. Intracellular starch levels were analyzed quantitatively using a Total Starch Assay Kit (AA/AMG; Megazyme) as described in Kajikawa et al. (2015). The cell volume was measured using a particle analyzer (CDA-1000; Sysmex).

Measurement of CO2 Concentration in the Culture Medium

Cell suspensions were centrifuged at 1,000g for 1 min to remove cells from the supernatant. Subsequently, five 10-μL aliquots of the supernatant were directly injected and total Ci concentrations were measured by using a gas chromatograph (GC-8A; Shimadzu) with a methanizer (MTN-1; Shimadzu), as described in Yamano et al. (2008). CO2 concentrations were calculated using the equation:

where pKa is the acid dissociation constant of 6.35, and using an HCO3–/CO2 of 4.47 at pH 7.0.

Subcellular Localization of LCIB-Clover

To obtain high-resolution fluorescence images, mutants were observed using a confocal fluorescence microscope TCS SP8 (Leica) equipped with a sensitive hybrid detector. LCIB-Clover was excited at 488 nm, and the emission was detected in a wavelength range of 500–520 nm. The images obtained were deconvoluted using Huygens Essential software (Scientific Volume Imaging) as described in Yamano et al. (2018).

Quantification of the Localization Patterns of LCIB-Clover

To quantify the localization pattern of LCIB, the CV of LCIB-Clover fluorescent signals was calculated. The CV value was defined as the ratio of the sd (σ) to the mean (μ) of LCIB-Clover fluorescent signals. Using the software Fiji/ImageJ (https://imagej.net/Fiji/Downloads), a cup-shaped chloroplast area except for the pyrenoid region was defined as the region of interest for an individual cell using the chlorophyll channel derived from confocal fluorescence microscopy images. The σ and μ of LCIB-Clover fluorescence intensity was quantified using the above-defined region of interest, and σ/μ was calculated.

TEM

Cells were fixed at 4°C overnight with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde and 2% (w/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The sections were postfixed with 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide in 0.1 m of phosphate buffer for 3 h at room temperature, then dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol solutions. After immersion in propylene oxide (Nacalai Tesque), samples were once again immersed in a mixture of propylene oxide and LUVEAK-812 (Nacalai Tesque) at 3:1, 1:1, and 1:3 each for 90 min, embedded in EPON 812 resin (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the inverted beam capsule procedure, and polymerized at 45°C overnight or 60°C for two nights. Ultrathin sections for TEM were prepared using an ultramicrotome EM UC6 (Leica). The ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined at ×12,000 magnification using a H-7650 TEM (Hitachi).

Calculation of the Starch Sheath Area

The cross-sectional area of the starch sheath around the pyrenoid was measured using the software ImageJ. TEM images were binarized to generate black images of the starch sheath. Then, the starch sheath was surrounded by an area selection tool, and the areas of the black regions were calculated.

Measurement of Photosynthetic O2-Evolution

Cells were harvested and suspended in Ci-depleted 20-mm MES-NaOH buffer (pH 6.2) or HEPES-NaOH buffer (pH 7.8) at 10 μg mL−1 chlorophyll. Photosynthetic O2-evolution was measured using a Clark-type O2 electrode (Hansatech Instruments), as described in Yamano et al. (2008).

Statistical Analyses

To assess the statistical significance of difference between photosynthetic affinities against Ci, two-tailed Student’s t test was used on biological replicates by using the software Microsoft Excel. Localization patterns of LCIB-Clover under different culture conditions were statistically evaluated by Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test using the software GraphPad Prism8 (https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/).

Accession Numbers

The accession numbers of Phytozome database for Chlamydomonas genes LCIB, ISA1, STA2, and STA11 are Cre10.g452800, Cre03.g155001, Cre17.g721500, and Cre03.g181500, respectively. The accession numbers of the GenBank database for ISA1 is AY324649.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Construction of the host strain for mutant screening.

Supplemental Figure S2. Subcellular localization of LCIB-Clover in mutants with aberrant LCIB localization.

Supplemental Figure S3. Accumulation levels of starch by iodine staining in AN-1, 4-D1, C1, and C2 cells.

Supplemental Figure S4. Starch content in the starch mutants.

Supplemental Figure S5. TEM images of the pyrenoid and starch sheath in starch wild-type and starch mutant cells.

Supplemental Figure S6. Subcellular localization of LCIB-Clover in starch mutants.

Supplemental Figure S7. Accumulation levels of starch by iodine staining in CC-4323, sta11-BC, and sta2-BC cells.

Supplemental Table S1. Genetic information of strains used in this study.

Supplemental Table S2. Photosynthetic parameters of wild-type and transformant cells at pH 7.8.

Supplemental Table S3. Photosynthetic parameters of wild-type and transformant cells at pH 6.2.

Supplemental Table S4. Sequences of primers used in this study.

Acknowledgments

Electron microscopic observation was supported by Keiko Okamoto-Furuta and Haruyasu Kohda (Division of Electron Microscopic Study, Center for Anatomical Studies, Graduated School of Medicine, Kyoto University). We thank Toshiki Matsuoka and Akihiro Nishimura (Graduated School of Biostudies, Kyoto University) for technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI grant nos. 16H04805 to H.F. and 16K07399 to T.Y., and Grant-in-Aid Research Fellow grant no. 17J08280 to C.T.), the Japan Science and Technology Agency, Advanced Low Carbon Technology Research and Development Program (grant no. JPMJAL1105 to H.F.), the Council for Science, Technology, and Innovation, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan (ImPACT program), and the Kyoto University Research Development Program (grant no. ISHIZUE 2019 to T.Y.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Badger MR, Kaplan A, Berry JA(1980) Internal inorganic carbon pool of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: Evidence for a carbon-dioxide concentrating mechanism. Plant Physiol 66: 407–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colleoni C, Mouille G, Gallant D, Bouchet B, Morell M, Samuel M, Delrue B, d’Hulst C, Bliard C, Nuzillard JM, et al. (1999) Genetic and biochemical evidence for the involvement of α-1,4 glucanotransferases in amylopectin synthesis. Plant Physiol 120: 993–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delrue B, Fontaine T, Routier F, Decq A, Wieruszeski JM, Van Den Koornhuyse N, Maddelein ML, Fournet B, Ball S(1992) Waxy Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: Monocellular algal mutants defective in amylose biosynthesis and granule-bound starch synthase activity accumulate a structurally modified amylopectin. J Bacteriol 174: 3612–3620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duanmu D, Miller AR, Horken KM, Weeks DP, Spalding MH(2009) Knockdown of limiting-CO2-induced gene HLA3 decreases HCO3− transport and photosynthetic Ci affinity in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5990–5995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel BD, Schaffer M, Kuhn Cuellar L, Villa E, Plitzko JM, Baumeister W(2015) Native architecture of the Chlamydomonas chloroplast revealed by in situ cryo-electron tomography. eLife 4: e04889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman Rosenzweig ES, Xu B, Kuhn Cuellar L, Martinez-Sanchez A, Schaffer M, Strauss M, Cartwright HN, Ronceray P, Plitzko JM, Förster F, et al. (2017) The eukaryotic CO2-concentrating organelle is liquid-like and exhibits dynamic reorganization. Cell 171: 148–162 e19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Wang Y, Fei X, Wright DA, Spalding MH(2015) Expression activation and functional analysis of HLA3, a putative inorganic carbon transporter in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J 82: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura AK, Chan KX, Atkinson N, Pallesen L, Wang L, Reeves G, Patena W, Caspari O, Roth R, Goodenough U, et al. (2019) A Rubisco-binding protein is required for normal pyrenoid number and starch sheath morphology in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116: 18445–18454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S, Sun J, Wunder T, Tang D, Cousins AB, Sze SK, Mueller-Cajar O, Gao YG(2016) Structural insights into the LCIB protein family reveals a new group of β-carbonic anhydrases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 14716–14721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajikawa M, Sawaragi Y, Shinkawa H, Yamano T, Ando A, Kato M, Hirono M, Sato N, Fukuzawa H(2015) Algal dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase, triacylglycerol accumulation regulator1, regulates accumulation of triacylglycerol in nitrogen or sulfur deficiency. Plant Physiol 168: 752–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson J, Clarke AK, Chen ZY, Hugghins SY, Park YI, Husic HD, Moroney JV, Samuelsson G(1998) A novel α-type carbonic anhydrase associated with the thylakoid membrane in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is required for growth at ambient CO2. EMBO J 17: 1208–1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchitsu K, Tsuzuki M, Miyachi S(1988) Changes of starch localization within the chloroplast induced by changes in CO2 concentration during growth of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: Independent regulation of pyrenoid starch and stroma starch. Plant Cell Physiol 29: 1269–1278 [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhang R, Patena W, Gang SS, Blum SR, Ivanova N, Yue R, Robertson JM, Lefebvre PA, Fitz-Gibbon ST, et al. (2016) An indexed, mapped mutant library enables reverse genetics studies of biological processes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 28: 367–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YG, Mitsukawa N, Oosumi T, Whittier RF(1995) Efficient isolation and mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA insert junctions by thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR. Plant J 8: 457–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YG, Whittier RF(1995) Thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR: Automatable amplification and sequencing of insert end fragments from P1 and YAC clones for chromosome walking. Genomics 25: 674–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumbreras V, Stevens DR, Purton S(1998) Efficient foreign gene expression in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii mediated by an endogenous intron. Plant J 14: 441–447 [Google Scholar]

- Mackinder LCM.(2018) The Chlamydomonas CO2-concentrating mechanism and its potential for engineering photosynthesis in plants. New Phytol 217: 54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinder LCM, Chen C, Leib RD, Patena W, Blum SR, Rodman M, Ramundo S, Adams CM, Jonikas MC (2017) A spatial interactome reveals the protein organization of the algal CO2-concentrating mechanism. Cell 171: 133–147 e14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinder LCM, Meyer MT, Mettler-Altmann T, Chen VK, Mitchell MC, Caspari O, Freeman Rosenzweig ES, Pallesen L, Reeves G, Itakura A, et al. (2016) A repeat protein links Rubisco to form the eukaryotic carbon-concentrating organelle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 5958–5963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay RML, Gibbs SP(1991) Composition and function of pyrenoids: Cytochemical and immunocytochemical approaches. Can J Bot 69: 1040–1052 [Google Scholar]

- Meslet-Cladière L, Vallon O(2011) Novel shuttle markers for nuclear transformation of the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot Cell 10: 1670–1678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MT, Whittaker C, Griffiths H(2017) The algal pyrenoid: Key unanswered questions. J Exp Bot 68: 3739–3749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Yamano T, Yoshioka S, Kohinata T, Inoue Y, Taniguchi F, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Yamato KT, et al. (2004) Expression profiling-based identification of CO2-responsive genes regulated by CCM1 controlling a carbon-concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 135: 1595–1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motohashi K.(2015) A simple and efficient seamless DNA cloning method using SLiCE from Escherichia coli laboratory strains and its application to SLiP site-directed mutagenesis. BMC Biotechnol 15: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouille G, Maddelein ML, Libessart N, Talaga P, Decq A, Delrue B, Ball S(1996) Preamylopectin processing: A mandatory step for starch biosynthesis in plants. Plant Cell 8: 1353–1366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Lau CS, Walker CE, Rai AK, Prejean CI, Yates G, Emrich-Mills T, Lemoine SG, Vinyard DJ, Mackinder LCM, et al. (2019) Thylakoid localized bestrophin-like proteins are essential for the CO2 concentrating mechanism of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116: 16915–16920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta N, Sugimura T, Isozaki A, Mikami H, Hiraki K, Sakuma S, Iino T, Arai F, Endo T, Fujiwaki Y, et al. (2018) Intelligent image-activated cell sorting. Cell 175: 266–276 e13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi M, Pringle JR(2016) Robust transgene expression from bicistronic mRNA in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. G3 (Bethesda) 6: 4115–4125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posewitz MC, Smolinski SL, Kanakagiri S, Melis A, Seibert M, Ghirardi ML(2004) Hydrogen photoproduction is attenuated by disruption of an isoamylase gene in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 16: 2151–2163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramazanov Z, Rawat M, Henk MC, Mason CB, Matthews SW, Moroney JV(1994) The induction of the CO2-concentrating mechanism is correlated with the formation of the starch sheath around the pyrenoid of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Planta 195: 210–216 [Google Scholar]

- Sager R, Palade GE(1957) Structure and development of the chloroplast in Chlamydomonas. I. The normal green cell. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 3: 463–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarejo A, Martinez F, del Pino Plumed M, Ramazanov Z(1996) The induction of the CO2 concentrating mechanism in a starch-less mutant of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Physiol Plant 98: 798–802 [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Yamano T, Kajikawa M, Hirono M, Fukuzawa H(2014) Isolation and characterization of novel high-CO2-requiring mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Photosynth Res 121: 175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Yamano T, Takane S, Niikawa Y, Toyokawa C, Ozawa SI, Tokutsu R, Takahashi Y, Minagawa J, Kanesaki Y, et al. (2016) Chloroplast-mediated regulation of CO2-concentrating mechanism by Ca2+-binding protein CAS in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 12586–12591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Spalding MH(2006) An inorganic carbon transport system responsible for acclimation specific to air levels of CO2 in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 10110–10115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Spalding MH(2014a) Acclimation to very low CO2: Contribution of limiting CO2 inducible proteins, LCIB and LCIA, to inorganic carbon uptake in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 166: 2040–2050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Spalding MH(2014b) LCIB in the Chlamydomonas CO2-concentrating mechanism. Photosynth Res 121: 185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunder T, Cheng SLH, Lai SK, Li HY, Mueller-Cajar O(2018) The phase separation underlying the pyrenoid-based microalgal Rubisco supercharger. Nat Commun 9: 5076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Asada A, Sato E, Fukuzawa H(2014) Isolation and characterization of mutants defective in the localization of LCIB, an essential factor for the carbon-concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Photosynth Res 121: 193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Fukuzawa H(2009) Carbon-concentrating mechanism in a green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, revealed by transcriptome analyses. J Basic Microbiol 49: 42–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Iguchi H, Fukuzawa H(2013) Rapid transformation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii without cell-wall removal. J Biosci Bioeng 115: 691–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Miura K, Fukuzawa H(2008) Expression analysis of genes associated with the induction of the carbon-concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 147: 340–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Sato E, Iguchi H, Fukuda Y, Fukuzawa H(2015) Characterization of cooperative bicarbonate uptake into chloroplast stroma in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 7315–7320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Toyokawa C, Fukuzawa H(2018) High-resolution suborganellar localization of Ca2+-binding protein CAS, a novel regulator of CO2-concentrating mechanism. Protoplasma 255: 1015–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Tsujikawa T, Hatano K, Ozawa S, Takahashi Y, Fukuzawa H(2010) Light and low-CO2-dependent LCIB-LCIC complex localization in the chloroplast supports the carbon-concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 1453–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y, Marchand CH, Maes A, Mauries A, Sun Y, Dhaliwal JS, Uniacke J, Arragain S, Jiang H, Gold ND, et al. (2018) Pyrenoid functions revealed by proteomics in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. PLoS One 13: e0185039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]