Abstract

State-of-the-art in vitro methods characterize receptor-ligand interactions, highlighting experiment strategies, advantages and limitations.

In plants, receptor-ligand interactions govern and monitor a large number of physiological processes, including growth, plant development, immunity, and interactions with the environment among other biological responses. By sensing and binding to ligands, receptors activate or inhibit biochemical signaling pathways to regulate cellular processes (Lumba et al., 2010; Couto and Zipfel, 2016; Hohmann et al., 2017, 2018a; Moussu and Santiago, 2019). Identification of key players and characterization of their biochemical interactions are fundamental for understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate these processes. A crucial aspect of unraveling the biochemical mechanisms behind cell communication is quantification of the different parameters that drive the formation of signaling complexes (Du et al., 2016). Nowadays, there are different techniques available to quantify biomolecular interactions that provide binding affinity (how strong the interaction is between two molecules), kinetics (how fast the interaction happens), and ligand specificity (how specific the interaction is between two molecules). This review aims to provide an overview of state-of-the art in vitro ligand-binding assays to investigate receptor-ligand interactions. An extensive review on methods for the analysis of protein-protein interactions in vivo was recently published by Xing et al. (2016). In addition to introducing method principles and new developments, we highlight the advantages and limitations (summary in Tables 1–3) and provide recommendations with the aim that readers may use this information as a reference when choosing the most suitable protein/receptor-ligand interaction technique(s) to study their system. For reference, we have also included a number of examples of plant ligand-receptor interactions characterized with different methodologies described below (Table 4).

Table 1. Summary of label-free methods discussed in this review.

$–$$$$ represents the cost of equipment, consumables, and protein sample.

| Description | ITC | SPR, GCI, BLI, QCM-D | AUC | DSF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Measures the binding enthalpy variation by sensing the heat generated by the binding reaction. | These optic and acoustic-based methods measure the binding kinetics. They measure the changes in mass, when the ligand binds to the receptor. | Monitoring of the sedimentation of components in a sample based on size and shape. | Thermal unfolding of a receptor investigated in the presence of a stabilizing ligand. |

| Affinity range | nm–µm | nm–mm and pm–mm | pm–mm | nm–mm |

| Thermodynamics | Yes | Yesb | No | Yesc |

| Kinetics | No | Yes | No | No |

| Sensitivitya | Low | High | Medium | Medium |

| Advantages | Thermodynamics are determined at a single experiment. No immobilization or labeling required. | Very low quantities of sample. Compatible with crude samples. QCM-D: mass changes include associated solvent allowing associated conformational changes. Sensor coating is more versatile. | No labeling required. Fluorescent tags may enhance the capabilities of the technique in high-affinity systems. | Relatively easy, cheap, and fast method. Low quantities of sample. |

| Limitations | High sample concentrations Heat release due to dilution effects. Slow binding processes may be difficult to study. | Immobilization of one interacting partner is required. Unspecific binding may be problematic. QCM-D: lower flow rate with potential noise in mass transport effect cases. | Large amount of sample required. Relative long duration of the experiment. High expertise needed to analyze the data. | Incompatibilities due to protein nature. Parameters are obtained at relatively high temperatures. |

| Financial aspects | Requires specialized equipment and high amount of protein. | Requires specialized equipment and proprietary consumables (i.e. chips, optic fibers). | Requires specialized ultracentrifuge with an optical arm and specialized cells and rotor. | It can be performed using specialized equipment but also in a standard quantitative PCR. May require a protein dye. |

| $$$ | $$$ | $$$$ | $$ |

Sensitivity is relative to the required sample concentration.

Thermodynamic parameters can be obtained through the measurement of Kd at different temperatures.

Thermodynamic parameters are extrapolated from the protein’s melting point.

Table 3. Summary of structure-based methods discussed in this review.

$–$$$$ represents the cost of equipment, consumables, and protein sample.

| Description | NMR | HDX-MS | SAXS and WAXS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | NMR analyzes the magnetic characteristics of specific nuclei, which absorb electromagnetic radiation when exposed to a magnetic field. | This method measures the reduction on hydrogen deuterium exchange rate through a series of increasing concentration of ligand. | This method is based on comparing light scattering profiles between the apo-receptor and the receptor-ligand complex. |

| Affinity range | nm–mm | nm–mm | nm–mm |

| Thermodynamics | No | No | No |

| Kinetics | No | No | No |

| Sensitivitya | High | High | Low |

| Advantages | Provides useful structural information of the receptor-ligand complex. | Low amount and concentration of sample is required. Provides identification of binding site. Applicable to intrinsically disordered proteins. | Provides information about conformational changes. Compatible with very high Mr systems. |

| Limitations | Requires isotope labeling. Restricted to low molecular mass receptors. | Dependent on the size of the peptides due to sample digestion process. | Access to synchrotron light source facilities. High sample concentration. |

| Financial aspects | Requires a specialized NMR equipment and high amount of protein and labeling. | Requires specialized equipment. | Requires a synchrotron facility or in-house SAXS/WAXS source. |

| $$$$ | $$$$ | $$$$ |

Sensitivity is relative to the required sample concentration.

Table 4. Some examples of plant ligand-receptor pairs.

Table 2. Summary of labeled-ligand methods discussed in this review.

$–$$$$ represents the cost of equipment, consumables, and protein sample.

| Description | FA | MST | FRET | Radiolabeling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Polarized light is used to analyze the change in rotational time of molecules. | This method is based on measuring the movement of molecules in a temperature gradient. | Fluorescence measurements of donor/acceptor pairs in close proximity (energy transfer). | Radioactive labeled ligand is applied to detect its binding to a receptor. |

| Affinity range | nm–mm | pm–mm | nm–mm | nm–mm |

| Thermodynamics | Yesb | Yesb | No | No |

| Kinetics | Yesc | No | No | No |

| Sensitivitya | High | High | Medium | High |

| Advantages | The method is label-free compatible using intrinsic fluorescence. Small amount of sample. | Very low quantities are required. Label-free compatibility due to intrinsic fluorescence. | The use of fluorescence tags in both, receptor and ligand facilitate accurate concentration measurements. | Very useful in systems with limited amount of receptor and/or ligand due to high sensitivity. Compatible with membrane proteins. |

| Limitations | Small differences in size between the bound and unbound forms. | Hydrophobic fluorescent dyes can produce unspecific binding. | The FRET pair needs to be in close proximity for efficient energy transfer. | Requires the use of radioactive material. |

| Financial aspects | Requires fluorescence spectrophotometer with light polarizers. | Requires specialized equipment and capillaries and a protein labeling kit. | Requires a spectrophotometer with desired filters. | Requires radioactive labeling, specific facility and licensing. |

| $$$ | $$$ | $$ | $$ |

Sensitivity is relative to the required sample concentration.

Thermodynamic parameters can be obtained through the measurement of Kd at different temperatures.

Through time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy.

The following points should be considered before starting your experiment:

(1) What type of technology is more suitable to study your system? A few aspects can determine that decision, such as the stability of your receptor protein, the solubility and chemical nature of your ligand, the receptor-ligand size ratio, or the nature of the binding process.

(2) Quality of your samples. In order to be able to interpret your results accurately, a good starting point is crucial. Receptor protein samples should always be checked for their integrity. Protein samples should be pure, and not aggregated or degraded, to ensure their best performance in the assays. Size-exclusion chromatography (purity and folding) or circular dichroism (folding) followed by SDS-PAGE (purity and degradation) should be standard techniques used to assess sample quality. The same is applicable to the ligands. Moreover, if the ligand has a synthetic origin, it is always important to take into consideration whether it has been precipitated with particular salts or chemicals, which could affect the experiment.

(3) Protein and ligand concentration. Accuracy with protein and ligand concentrations is key to quantifying a biomolecular interaction.

(4) Environmental conditions. Taking into consideration the natural environmental conditions where the interaction takes place can be helpful to perform the experiments in a mimicked biochemical context (e.g. the pH under which the interaction would likely take place in the cell).

LABEL-FREE LIGAND BINDING ASSAYS

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

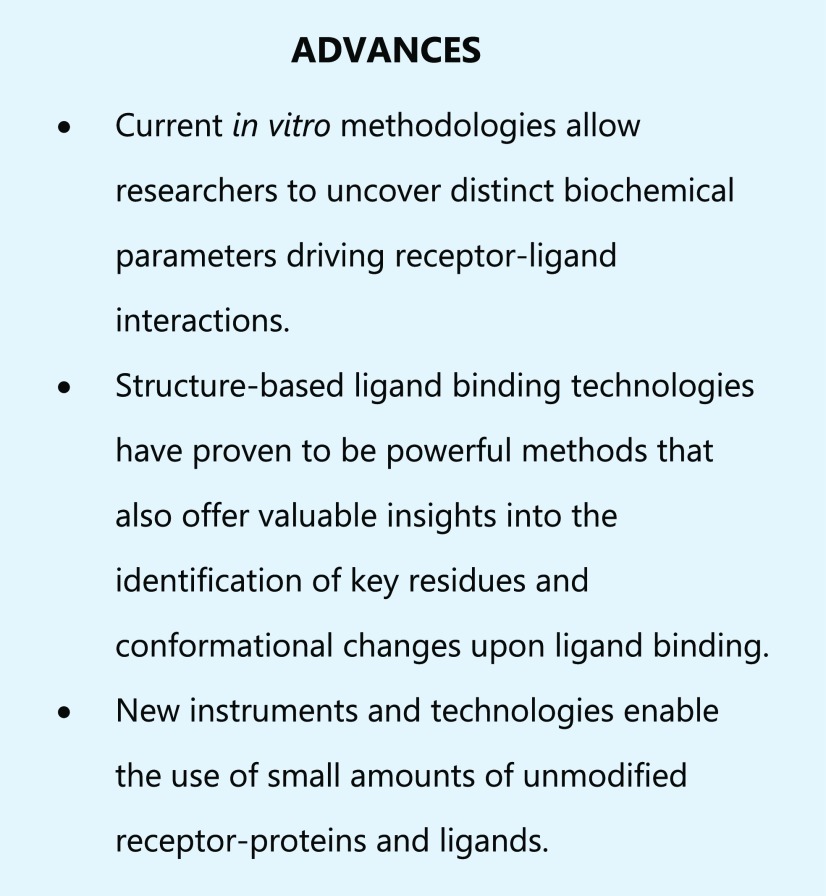

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) is a label-free technique that allows direct measurement of heat exchange during complex formation, providing information on the thermodynamics of biomolecular binding processes. ITC measures the heat released or absorbed during the binding reaction and allows the distinction between enthalpic and entropic contributions to the binding mode. ITC is particularly reliable in measuring entropy-driven interactions (Freire et al., 1990; Freyer and Lewis, 2008; Falconer, 2016). ITC instruments make use of a power compensation system that is responsible for maintaining the same temperature between the sample cell (containing the receptor protein) and the reference cell, typically filled with water or buffer. During the course of the experiment, a titration system injects precise amounts of ligand to the sample cell; this causes heat to be released or absorbed (depending on the nature of the reaction), and consequently, a temperature imbalance between the sample and the reference cell will occur. Such imbalance is then rapidly compensated by modulating the feedback power applied to the cell heater (Franks et al., 2012). The overall measurement of the system consists of the power applied to the sample cell as a function of time, to maintain equal temperatures between the sample and the reference cell at each ligand titration. The thermogram generated consists of a series of peaks that return to baseline, with the area of each peak corresponding to the heat released or absorbed at each ligand injection (Fig. 1; Freyer and Lewis, 2008; Du et al., 2016). As the receptor-binding site becomes saturated with ligand, the peak area decreases gradually until only dilution heat is observed. The binding curve (Fig. 1) represents the heat of the reaction per titration/injection as a function of the molar mass ratio between the ligand and the receptor protein. Fitting the binding curve to a specific binding model (Indyk and Fisher, 1998; Freiburger et al., 2015) provides the parameters Kd (dissociation constant), ΔΗ (enthalpy), and n (stoichiometry; Fig. 1). ITC enables reliable determination of dissociation constants (Kd) between 1 nm and 100 μm (Freyer and Lewis, 2008). Lower Kd values can be determined by performing a displacement assay, if a competitive ligand is available (Krainer and Keller, 2015). It is important to keep in mind that the heat recorded in an ITC experiment is the total heat effect released or absorbed in the sample cell upon addition of the ligand. This means that heat effects arising from dilution of the ligand and protein, differences in buffer composition between samples, etc., will also be accounted. Therefore, appropriate control experiments are necessary to remove the nonspecific heat effects from the experiment.

Figure 1.

Cartoon of overview of label-free methods. A, Schematic of an ITC instrument and an ITC thermogram (raw data), which provides information about affinity, stoichiometry, and thermodynamics. B, Schematic representation of surface-based optics methods (SPR, GCI, and BLI). At least one of the receptor or ligand needs to be immobilized. Recent developments allow for preferential orientation of molecules on the chip surface. Typical curves of a titration experiment are shown in the sensogram (low and high concentrations of ligand are represented in light blue and black, respectively). C, Schema of QCM-D principle. One of the biomolecules is immobilized on a quartz surface and voltage is applied through to the quartz disc to make it oscillate. The frequency of oscillation (f) is very sensitive to small fluctuations of mass on the surface. Structural properties are measured as changes in dissipation (D) after cutting the electrical power. D, Illustration of the principle of AUC. Buffer and a sample containing known concentrations of receptor and ligand are placed in a double-sector cell and high centrifugation speed is used to sediment the components of the sample while a radial scanner monitors sedimentation. In sedimentation velocity, the data obtained are modeled using hydrodynamics theory to calculate the size and proportions of the sedimented molecules. Fluorescence tags can be used to improve detection. E, In a DSF assay, the thermal unfolding of a receptor is monitored in the presence of increasing concentrations of ligand. The Kd is obtained at the ∼Tm of the free receptor. The method can use intrinsic Trp fluorescence or compatible dyes.

There are a few recommendations that might be helpful before you start your ITC experiment. Both the ligand and the receptor buffer/solutions have to be identical to avoid buffer mismatch artifacts. The concentration of the ligand injected should be high enough to reach saturation within the first third to half of the experiment. As a starting point, you can calculate a concentration 10 times higher than that of the receptor protein in the sample cell (e.g. 10 μm in the sample cell versus 100 μm of the ligand in the syringe). In principle, ITC is compatible with aqueous buffers in the range pH 2–12; however, you may want to avoid amine buffers such as Tris, which have a large enthalpy of ionization. So if you are not interested in quantifying the number of protons released or taken up in your binding reaction, you could substitute the Tris buffer with HEPES or phosphate buffer. If you need glycerol in your experiment, keep it below 20% to avoid bubbles and heat distortions. Similarly, if reductants are needed to maintain reduced cysteines, avoid dithiothreitol and use Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine at low concentrations. Also, the presence of organic solvents can cause signal artifacts, so if dimethyl sulfoxide is needed, keep it below 10% in all your solutions (Duff, et al., 2011).

This technique has a number of advantages compared to other biophysical methods; it determines direct thermodynamic binding parameters, samples do not get altered or modified, the interaction is measured in solution, and it is a very robust and highly sensitive technique. Moreover, it has no size limitation when it comes to protein-ligand samples. However, it also has certain limitations; kinetics of the interaction cannot be determined, it is not the best performing method for slow binding processes, and it requires larger amounts of sample than other methods, which sometimes can be limiting. New developments are focused on addressing these disadvantages with new systems that are more sensitive and require less sample per experiment (e.g. PEAQ-ITC [Malvern] and NanoITC [TA Instruments]). Traditionally, this technique was categorized as a low-throughput and time-consuming method, but this situation is now changing with the appearance of robotic instruments that do cell loading and data collection in an automated manner, thus enabling high-throughput experiments.

ITC has been broadly used to characterize very distinct plant receptor-ligand interactions in a broad range of binding affinities (Santiago et al., 2009, 2016; Liu et al., 2012; Hohmann et al., 2018b; Xiao et al., 2019).

Optical Biosensing Technologies

The following technologies are optical-based methods capable of measuring real-time protein-ligand kinetics and affinities. In all three methods, the protein receptor molecules are typically immobilized on the sensor surface, and the ligand (called the analyte) is then injected to flow across it. After a specific association time, determined by saturation of receptor binding sites, a solution containing no ligand is injected through the flow cell to dissociate the receptor-ligand complex (Fig. 1). Ligand association and dissociation from the receptor will translate into changes in the interference pattern of light. These changes, based on the number of ligand molecules bound to the receptor on the surface, are depicted in a sensogram, from which the kinetic association constant (Ka) rate (kon) and the dissociation constant rate (koff) can be calculated, and from which the Kd can be subsequently derived (Fig. 1).

These types of experiments should be performed with various concentrations of the analyte. The concentration range should span from 10× below to 10× above the Kd. It is crucial to accurately measure the analyte concentration to determine a specific binding constant. To avoid optical effects from buffer differences, the ligand (analyte) should be diluted in the same running buffer used for the experiment. If the diffusion rate is slower than the association rate of the ligand, mass transfer effects can be observed that alter the accuracy of the experimental kinetics. This problem can be overcome by increasing the flow rate of the experiment or lowering the receptor density on the surface.

One of the big advantages of these optical biosensing methods is that, compared to ITC, they all require much smaller amounts of receptor sample.

Surface Plasmon Resonance Spectroscopy

A surface plasmon resonance (SPR) phenomenon occurs at metal surfaces (typically gold and silver) when a p-polarized light-beam strikes the surface at a certain angle. SPR is extremely sensitive to small changes in the refractive index of the medium very close to the metal surface, which makes it possible to measure, with high accuracy, the absorption of molecules and their eventual interactions with specific ligands (Olaru et al., 2015).

SPR was developed and performed predominantly using Biacore technology (Raghavan and Bjorkman, 1995). Compared to ITC, SPR has the ability to measure higher binding affinities in the picomolar to millimolar range (Jain et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2019). It is a sensitive and robust method; however, experimental design and results analysis require higher expertise. Recent developments in SPR instrumentation and sensor chip design are making this technology compatible with performance of high-throughput ligand screening and work with membrane proteins (Kyo et al., 2009; Maynard et al., 2009; Olaru et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019a).

Grating-Coupled Interferometry

Interferometric and surface plasmon affinity sensors are based on the same physical effect: they both detect tiny changes in the refractive index profile close to the waveguide surface. This region is probed by the evanescent field of the waveguide, which undergoes a characteristic phase delay upon interaction of the ligand (analyte) with the receptor protein coupled to on the sensor surface (Lukosz, 1991; Kozma et al., 2009). Compared to conventional interferometry, grating-coupled interferometry (GCI) technology drastically improves the stability of the detected signal by coupling the reference and measuring light waves into the same waveguide, thus removing drifts originated by thermal and/or mechanical shifts of the optics (Kozma et al., 2011). This technology has been made commercially available by Creoptix AG. GCI has been proven to be more sensitive than SPR technology (Lukosz, 1991; Patko et al., 2012) in that a greater amount of surface is probed by each evanescent wave. In fact, each evanescent wave in SPR technology typically covers a surface area of ∼100 nm diameter, while the evanescent wave in GCI covers the whole 2-mm length of the sensor surface (Kozma et al., 2011; Patko et al., 2012), thereby probing more interactions than the SPR wave. The higher sensitivity of GCI instruments enables them to resolve reliable kinetics with very low responses, thus allowing researchers to study binding interactions between molecules with very large molecular weight ratios (e.g. hundreds of kilodaltons of immobilized ligands versus 200 D of small molecule analytes) and to work with ligands of much lower activity and with low surface densities of immobilized receptor on the surface (Creoptix.com/applications). Unlike SPR Biocore instruments, the GCI device designed by Creoptix AG has neither microfluidic channels nor microvalves. Instead, the microfluidics are built into the disposable chip. This makes the device compatible with crude samples (e.g. cell culture media, unpurified cell lysates, lipidic vesicles, etc.) and allows faster transition times, thus resolving very fast on- and off-rates, expanding the range of measurable kinetics with optical biosensing of affinities from the low picomolar range to tens of millimoles (Hohmann et al., 2018b; Creoptix.com/applications).

GCI has been used recently to shed light on ligand perception and signal activation by receptor kinases (Hohmann et al., 2018a, 2018b; Okuda et al., 2020).

Biolayer Interferometry

Biolayer interferometry (BLI) uses white light interferometry to measure biomolecular interactions. This technique analyzes the interference pattern of the light reflected between two surfaces, the layer of an immobilized receptor on the biosensor tip and an internal reference layer (Concepcion et al., 2009). Since the measurement is performed using optical fibers instead of a fluidic system, the technology is compatible with sample delivery in 96- or 384-well plates, allowing for high-throughput screening (Wartchow et al., 2011). BLI technology was mainly developed by FortéBio. Other interesting features of BLI instruments are their ease of use, with no high maintenance required, and compatibility with crude samples, since only molecules binding or dissociating from the biosensor can shift the interference pattern (Petersen, 2017). The major drawback of this technique is that it is ∼100-fold less sensitive than SPR or GCI and thus less likely to detect binding of small molecules. BLI detects affinities in the nanomolar to micromolar range. In addition, the fact that measurements are carried out in a well compromises the accuracy of the kinetic parameters obtained with BLI, as compared to SPR or GCI parameters, which are obtained under dynamic flow conditions. This technique was used to show, for the first time, the specific interaction between Leu-rich repeat extensin (LRX) proteins and rapid alkalinization factor (RALF) peptides (Mecchia et al., 2017).

It is important to keep in mind that all of these methods require immobilization of one of the binding partners, potentially modifying its conformation and/or binding surface and affecting the association rate (Du et al., 2016). In order to address this problem, chip engineers of all technologies have opted for the development of different coated chips that allow the coupling of the receptor molecules to the surface through specific tags. An example is the development of streptavidin-coated chips where biotinylated proteins and ligands can be coupled in a particular orientation (Fig. 1; Hutsell et al., 2010; Lorenzo-Orts et al., 2019; Okuda et al., 2020).

Quartz Crystal Microbalace and Quartz Crystal Microbalace with Dissipation

Quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) is another powerful surface sensing method that also monitors changes in mass in real time. In essence, a quartz crystal microbalance is a very sensitive scale able to weigh a few billionths of a gram. The heart of QCM technology is a quartz crystal oscillator. Quartz is referred to as a piezoelectric material (Curie, 1889; Cady, 1964), which means that it can be made to oscillate at a defined frequency by applying an appropriate voltage through metal electrodes directly attached to the quartz disc. The frequency of oscillation (f) is sensitive to the addition or removal of small amounts of mass at the sensor surface (Fig. 1C; Liu et al., 2011). QCM with dissipation (QCM-D), an extended version of the technique, allows for applications of this technology in liquid media (Nomura and Hattori, 1980). Liquid-media QCM has been used in different fields of biology to measure kinetics of molecular interactions (e.g. protein–protein interactions) and molecule-surface interactions (e.g. the affinity of biomolecules to surfaces functionalized with recognition sites), and to generate polymer films and measure their interactions with different soluble constituents or biosensor applications (Laricchia-Robbio and Revoltella, 2004; Dixon, 2008; Lee et al., 2015). QCM-D, similar to SPR or GCI, senses relative changes of mass coupled to the surface; however, due to the different principles by which the coupled mass is measured, the mass measured by SPR/GCI is referred to as optical or “non-hydrated”, whereas the mass measured by QCM-D is referred to as acoustic or “hydrated”. This means that in an SPR/GCI experiment, water associated with, for instance, a protein film (e.g. hydration shell) is essentially not included in the mass determination. In contrast, QCM-D senses both the macromolecules and the solvent coupled to it (Dixon, 2008; Liu et al., 2011). This makes QCM-D able to measure macromolecular reorganization and conformational changes due to changes in water content. This additional information contained in the dissipation factor allows for a more detailed interpretation of the surface of interaction and reaction processes (Dixon, 2008).

Both SPR/GCI and QCM-D technologies can monitor time-resolved mass changes and evaluate kinetics in the nanomolar to millimolar range (Laricchia-Robbio and Revoltella, 2004; Lee et al., 2015). However, SPR/GCI technologies are better methods for characterizing kinetics and affinities. Moreover, SPR/GCI instruments have smaller sample cell volumes and can achieve faster flow rates, which is beneficial in reducing potential mass transport effects. On the other hand, QCM-D is more sensitive for water-rich and extended layers and the sensor coating is much more versatile. This allows for surface interaction studies with different biological surfaces and polymers, such as cell wall fractions.

Analytical Ultra-Centrifugation

Analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) is a classical first-principle method of physical biochemistry that is very versatile and powerful for the investigation of protein interactions. The method is based on protein mass and gravity, where sedimentation is used to analyze the protein behavior in a series of ligand concentrations to calculate binding affinities. Sedimentation velocity (SV) measures the rate at which molecules move in response to centrifugal force, providing hydrodynamics about size and shape, whereas for sedimentation equilibrium (se), the final equilibrium distribution is examined, providing association constants and stoichiometry (Cole and Hansen, 1999; Howlett et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2013). AUC uses ultracentrifuges for high-speed centrifugation, typically ranging from 200,000g to 1,000,000g. The machine uses optic components for monitoring protein sedimentation over time, with sedimentation depending on protein mass (large proteins sediment faster). A two-sector cell is filled with buffer (as a reference) and with the sample containing the protein-ligand mixture (Fig. 1). Sedimentation starts upon high-speed centrifugation and the detector keeps monitoring it during the course of the experiment, typically 16 h. The detector measures protein absorbance at a single wavelength (190–800 nm; Fig. 1; Cole et al., 2008); however, the use of multiple wavelengths is also possible, allowing for spectral deconvolution of interacting and noninteracting components in the sample (Johnson et al., 2018). In an SV experiment, binding affinities can be calculated through ligand titration and by plotting the sedimentation coefficients as a function of the receptor-ligand ratio (Fig. 1; Zhao et al., 2013). The main limitations of this technique are the larger amount of sample required, the expensive equipment, and the high expertise required to analyze the data. On the other hand, it is a very robust method and typically label free, though it is compatible with the use of fluorophores for better resolution of high-affinity systems (in the picomolar to millimolar affinity range) using fluorescence-detected SV (Zhao et al., 2014).

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry

Differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF), also known as thermal shift assay, is a technique that measures protein thermal denaturation under different buffer compositions. This method has been widely used to determine the melting temperature (Tm) of proteins in the presence of ligands through the use of fluorescent dyes, GFP tags, or intrinsic Trp fluorescence in a label-free version (Lo et al., 2004; Royer, 2006; Moreau and Schaeffer, 2013). Besides providing evidence of direct interactions, most equilibrium binding ligands increase protein stability, which increases the Tm of the protein so that binding affinity and stoichiometry can be calculated (Matulis et al., 2005; Bai et al., 2019). DSF monitors sample fluorescence in a gradual temperature ramp, where the Tm can be extracted from the resulting thermal unfolding curves (Fig. 1). The change in protein stability (Tm) as a function of ligand concentrations serves to calculate the binding affinity at a certain temperature (close to the Tm). Different methods have been published using DSF to calculate Kd values, and affinities have been reported in the nanomolar to micromolar range. However, it is important to keep in mind that these calculations are indirect, and they require known values of unfolding enthalpy, as well as extrapolation to lower temperatures (Matulis et al., 2005). A more simplified method that uses denaturants to alter protein stability (e.g. guanidine hydrochloride) may aid in the determination of binding affinities at temperatures lower than the Tm (Bai et al., 2019). The measurements are made in a standard quantitative PCR machine or in a nanoDSF instrument (Magnusson et al., 2019) within 2–3 h. This technique also has certain limitations regarding the protein sample: low intrinsic fluorescence of the receptor protein (not all proteins contain Trp residues), high protein hydrophobicity (dye-protein complex formation), and low or no stability gain after ligand binding. On the other hand, the amount of protein required is very low (in the range of 5 μm in a sample volume of 10–20 μL).

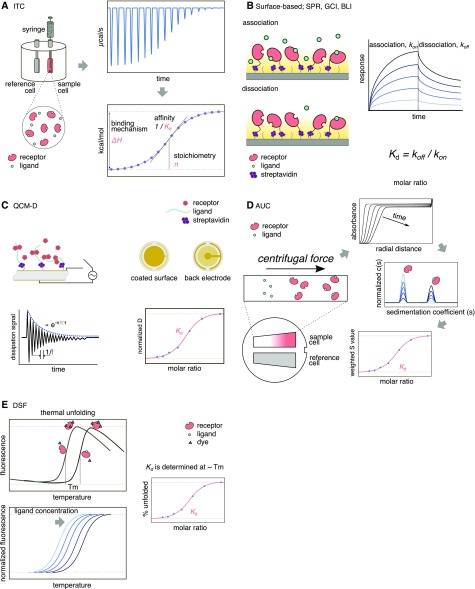

Fluorescence Anisotropy

Fluorescence anisotropy (FA) uses polarized light to excite fluorophores; the emitted light is partially polarized due to the changing orientation of the molecules in solution (rotation of the fluorophore dipole; Fig. 2). In essence, FA is based on changes in the hydrodynamic radius of the fluorophore due to interaction with a binding partner. Other factors, like viscosity of the solvent and size and shape of the rotating molecule, can affect this value. Anisotropy measurements are performed with standard fluorescence spectrometers using plane-polarized excitation light, where the fluorescence emitted is then measured with a second polarizer (in vertical and horizontal orientations relative to the plane of the optics). The hydrodynamic radius of a ligand is drastically affected upon binding to a receptor, and this affects the amount of polarized light emitted, described in terms of anisotropy (r), which corresponds to the ratio of the polarized component to the total intensity (Lakowicz, 2006; Zhang et al., 2015). The resulting anisotropy curves can then be fitted to different binding models (Fig. 2). This is a dual technique, since it is compatible with label-free techniqiues due to the intrinsic Trp fluorescence of proteins; however, the use of fluorescence tags (e.g. GFP) or chemically attached fluorophores is often adopted to increase sensitivity. For higher resolution, it is preferable to have a considerable change in size in the final complex relative to the apo-molecule. In the case of fluorophore usage, the selection of dyes is based on the lifetime and size of the interactors (Zhang et al., 2015). The binding affinity for FA ranges from nanomolar to millimolar. Time-resolved FA is a variant of this method that allows for determination of kinetic parameters (Kapusta et al., 2003; Veiksina et al., 2014).

Figure 2.

Cartoon of overview of labeled methods. A, Depiction of FA principle. The sample is irradiated with polarized light (vertical) and the detector can filter the resulting light with a second polarizer that changes from vertical to horizontal. The rotational speed of molecules correlates with the depolarization of light. The anisotropy value, r, is related to the movement of the molecules in the sample: the bigger the molecule (i.e. receptor/ligand complex), the slower the rotation speed compared to the free ligand, which will lead to less depolarized light, increasing the r value. The method can use intrinsic fluorescence of molecules as well as fluorophores. B, Representation of MST. A focus IR-laser generates a temperature gradient spot in the sample, inducing molecule displacement (thermophoresis). A detector monitors the sample spot, tracking the displacement of the sample. C, In FRET, a compatible donor/acceptor pair is required. The reduction in the signal of the donor (quenched) is used to generate a dose response graph. The donor and acceptor molecules need to be in close proximity (10 nm or less) for efficient energy transfer. D, Representation of a typical radioligand binding assay. In competition binding, the receptor is mixed in the presence of label-free and radiolabeled ligand. After incubation, the receptor is removed from the sample and the amount of unbound radioligand is used to calculate binding affinities.

LABELED LIGAND BINDING ASSAYS

Microscale Thermophoresis

Microscale thermophoresis (MST) is a powerful technique that can be used to measure dissociation constants and thermodynamic parameters. It measures the movement of molecules along microscopic temperature gradients, which strongly depends on molecular properties such as size, charge, conformation, or hydration shell. Thus, this technique is highly sensitive to changes in molecular properties, allowing for precise quantification of molecular events (Jerabek-Willemsen et al., 2014). MST requires sample labeling with a fluorophore and monitors the movement of the fluorescent molecules into a capillary where an infrared laser has been focused to produce a microscopic temperature gradient (Fig. 2). During the induction of this temperature gradient, the emitted fluorescence is then collected through the same objective as the infrared laser, allowing for the recording of dependent depletion or accumulation of fluorophores within the induced temperature gradient (Fig. 2). Thermophoresis of the apo-protein typically differs from that of the protein-ligand complex due to the change in size and solvation entropy. To derive binding constants, thermophoresis is recorded using a titration approach, where increasing concentrations of ligand are added to capillaries containing a constant concentration of labeled-receptor protein in solution. The thermophoresis signal is plotted against the ligand concentration to obtain a dose-response curve, from which the binding affinity can be calculated (Fig. 2; Jerabek-Willemsen et al., 2014).

When performing an MST experiment, a few considerations may help to optimize the experimental conditions. The concentration of labeled molecule (receptor or ligand) should be in the range of the Kd or lower. Concentrations of the binding partner that are too high could cause a significant shift on the inflection point of the dose-response curve, leading to inaccurate determination of the dissociation constant. To avoid sample evaporation, it is convenient to use wax to seal the capillaries right after preparing the dilution mixes. Another important consideration is the noise. In an MST experiment, the main source of noise is poor sample quality, meaning, for instance, that aggregates are present in the solution. Sample quality can be assessed at the purification step, but additives like detergents or bovine serum albumin can be used to enhance the stability of the protein during the experiment if necessary (Jerabek-Willemsen et al., 2011).

Similar to ITC, MST is measured in solution and does not require protein immobilization. Measurements are done in capillaries that hold only ∼3–5 μL, so it also does not use large amounts of sample, and it is compatible with any buffer. It is a fast technique that covers the picomolar to millimolar dynamic affinity range (Jerabek-Willemsen et al., 2014; Wild et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2019), and it is comparable to SPR and GCI measurements. However, when hydrophobic fluorescent labels are used, they can potentially modify the structural and chemical nature of the protein samples as well as promote nonspecific binding. New MST instruments (e.g. MonolithNT, NanoTemper Technologies) equipped with different detector types allow for the detection of Trp fluorescence as well as for visible light between 480 and 720 nm to perform label-free experiments (Seidel et al., 2012; Jerabek-Willemsen et al., 2014).

Förster (Fluorescence) Resonance Energy Transfer

Förster (Fluorescence) resonance energy transfer (FRET) describes the phenomenon of transferring energy from a donor to an acceptor molecule in close proximity, typically <10 nm apart. The implementation of FRET requires the use of compatible fluorescent tags (donor and acceptor) for overlapping of the emission spectrum of the donor with the absorption spectrum of the acceptor (Fig. 2). FRET has been widely used for detection of in vivo molecular interactions using fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (Chen et al., 2003; Zelazny et al., 2007; Long et al., 2018; Glöckner et al., 2019). Despite its use in proving molecular interactions and localization, quantitative FRET has emerged as an interesting approach in the determination of binding affinities for characterization of protein-protein interactions (Martin et al., 2008; Song et al., 2012; Ghalali et al., 2019). Typically, recombinant fusion proteins are purified and analyzed in vitro. Different fluorescent tags (pairs) have been used: CFP/GFP, clover/mRuby2, YFP/CFP, or tags specially engineered for FRET (CyPet/YPet), among others (Martin et al., 2008; Song et al., 2012; Ghalali et al., 2019). The measurement consists of a steady-state binding assay. A fluorescence plate reader is used for monitoring the fluorescence emission spectra during the ligand titration. The emission curves obtained during the titration experiment are used to determine the binding affinity (Fig. 2; Song et al., 2012; Ghalali et al., 2019). Due to the spatial requirements for FRET to occur, the location of the fluorescent pairs must be carefully selected to satisfy the <10 nm separation distance to allow for energy transfer. The affinity range goes from nanomolar to millimolar, and the method is mainly limited to relatively large molecules, although significant engineering work has been done with characterization of interactions by FRET biosensors such as Arg (Bogner and Ludewig, 2007), inorganic phosphate (Mukherjee et al., 2015), Glc (Deuschle et al., 2006), and abscisic acid (Waadt et al., 2014) that have been tested in planta to estimate ligand concentrations.

Radioligand Binding Assays

Currently, radioligand binding assays are mainly used for membrane-bound receptors (Schaller and Bleecker, 1995; Hoare and Usdin, 1999; Bylund et al., 2004). There are three experimental types of radioligand binding assays: the competitive binding assay, the saturation assay, and the kinetic binding assay (Fig. 2; Maguire et al., 2012). Competitive assays analyze the equilibrium binding at a fixed concentration of the radioligand and in the presence of different concentrations of an unlabeled competitor. In contrast, in a saturation experiment, a homogenate/cell containing a fixed concentration of the receptor is incubated with increasing concentrations of the radioligand to calculate the dissociation constant (Kd). Kinetic assays are used to determine receptor/ligand specific association and dissociation constants, from which a kinetic Kd can be derived (Fig. 2). A more extended guide on how to perform and analyze this type of experiment can be found in Maguire et al. (2012) and Hellmuth and Calderón Villalobos (2016). An example is the measurement of ethylene binding to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane receptor ETR1 (Schaller and Bleecker, 1995).

This very sensitive method is compatible with membrane proteins, and it covers affinities up to the nanomolar range. The main drawback of this technique is the use of radioactive material, which besides being hazardous requires a specialized facility and licensing.

Chemiluminescence-Based Receptor-Ligand Assay

Chemiluminescent labels, such as acridinium-esters, have been successfully used as an alternative to radiolabeling to characterize receptor-ligand pairs (Weeks et al., 1983; Joss and Towbin, 1994; Butenko et al., 2014; Wildhagen et al., 2015). Acridinium-esters rapidly decompose in a stoichiometric manner upon addition of hydrogen peroxide in an alkaline environment, producing a strong light signal that can be detected using a luminometer (Adamczyk et al., 2002; Roda et al., 2003; de Jong et al., 2005). An advantage of this type of labeling over fluorescence systems is that little or no background is generated. However, something to bear in mind is the possibility of inhibition or enhancement of the signal by matrix components; therefore, it is prerequisite to make use of highly pure reagents (de Jong et al., 2005).

STRUCTURE-BASED LIGAND BINDING ASSAYS

In addition to providing information on receptor-ligand binding affinity, all of these techniques also offer valuable insights into the structural changes that occur upon ligand binding.

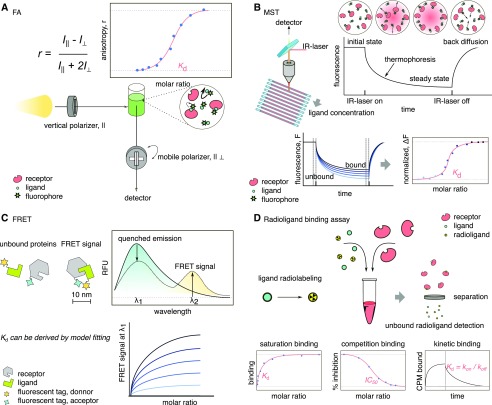

NMR

NMR spectroscopy is a well-known technique for studying intermolecular interactions. Protein-ligand complexes are studied using the so-called protein-observed and ligand-observed NMR approaches, in which the NMR parameters of the free and bound molecules are compared (Goldflam et al., 2012; Cala et al., 2014; Becker et al., 2018). NMR can provide affinities from the nanomolar to the millimolar range (Wild et al., 2016). In protein-observed methods, a spectrum of the receptor is acquired and the ligand is titrated. This provides information about the receptor residues involved in the direct interaction with the ligand, allowing for the mapping of the ligand binding site (Fig. 3). The major drawbacks of these protein-based methods are the experimental time and the need for highly stable and soluble receptor proteins. Moreover, these methods are limited to proteins with low molecular mass (∼30–50 kD), and they require protein isotope-labeling strategies and sequence resonance assignments (Cala et al., 2014; Becker et al., 2018). Conversely, in ligand-observed methods, a spectrum of the ligand is acquired and the receptor protein is added. The ligand can be a small molecule, a peptide, DNA, or another interacting protein (Fig. 3). In contrast with protein-observed methods, these experiments offer more sensitivity with larger proteins and require less protein sample without any labeling. Ligand-based methods can be used for the detection of specific interactions and the measurement of protein-ligand affinities, and they can also provide useful structural information on the receptor-ligand complex. Due to the lack of space in this review, we advise the reader to consult the following excellent reviews where different NMR methods to study protein-ligand interactions are described in detail (Cala et al., 2014; Becker et al., 2018).

Figure 3.

Cartoon of overview of structure-based methods. A, Scheme of NMR binding assays. The one-dimensional chemical shift uses labeled substrates, the height of the NMR ligand signal decreases upon binding with the receptor. In a two-dimensional chemical shift assay (bottom), the receptor is labeled with two isotopes and the NMR spectra are plotted. R1, R2, and R3 represent receptor amino acids that move upon ligand binding and are proportional to the amount of ligand. B, In an HDX-MS assay, the free receptor is incubated with heavy water, allowing amide hydrogen exchange with deuterium. The samples are digested and analyzed by MS to obtain the rates of deuterium uptake in different peptides. When the ligand is added to the receptor prior to deuterium exchange, some parts of the receptor will be “protected,” preventing HDX. The amount of deuterium obtained for some peptides will be inversely proportional to the amount of ligand. C, Principle of the light scattering techniques SAXS and WAXS. The scattering profile of samples containing increasing concentrations of ligand are compared and processed using the scattering profile of the buffer and that of the free receptor. Population modeling and model fitting are used to calculate the Kd.

Hydrogen Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry

Hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) is a powerful biophysics technique that can provide insights into protein dynamics, protein folding, protein-protein interactions, and protein-small molecule (ligand) interactions. HDX measures changes in mass linked with the deuterium exchange between amide hydrogens of the protein backbone and its surrounding solvent (Fig. 3; Masson et al., 2019). An HDX-MS experiment is divided into three main steps: (1) deuterium incorporation, (2) spatial localization of deuterium incorporation/exchange, and (3) data analysis. (1) Deuterium labeling can be carried out in a simple exchange reaction, where deuterium is incorporated through incubation of the protein with a deuterated buffer. This process is very sensitive to experimental conditions, such as pH or temperature fluctuations, so to assure reproducibility, experiments should be conducted in similar and optimal conditions. (2) To study protein-ligand interactions, the protein of interest (receptor) is incubated with the ligand(s) and the hydrogen/deuterium exchange can be spatially resolved using different techniques, as discussed in Masson et al. (2017). (3) Data analysis and interpretation are not always easy and require expertise. Readers are advised to consult excellent recent reviews for more comprehensive methodological details on how to perform, interpret, and report HDX experiments (Tu et al., 2010; Gallagher and Hudgens, 2016; Masson et al., 2017, 2019).

The advantages of this method are that it is highly sensitive (low nanomolar affinities), it requires low amounts of sample (nanomolar to low micromolar concentration), and it can be used to study potential conformational changes upon ligand binding and to identify the binding site.

Wide- and Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering

Wide- and small-angle x-ray scattering (WAXS and SAXS, respectively) are biophysical methods used to study structural features and changes in the physical behavior of proteins in solution (Fischetti et al., 2004; Kikhney and Svergun, 2015). SAXS reports the globally averaged distance distribution of scattering electron densities around all atoms. This distribution is obtained by measuring the higher signal intensity of the sample solution over the buffer solution (Fig. 3). To study a receptor-ligand interaction, the Kd can be measured by titrating receptor and ligand at a multiple ligand-receptor ratio and measuring the scattered photon intensity changes to the balance between the apo-receptor and the receptor-ligand complex (Fig. 3; Chen et al., 2019). The main difference between the two methods is that SAXS can only detect changes that alter the radius or gyration of proteins and protein complexes, whereas WAXS is an extension of SAXS in which data are collected at wider scattering angles. WAXS has been shown to be sensitive to secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structural features (Fischetti et al., 2004).

These methods need to be performed in a synchrotron facility. They are compatible with high-throughput target-based screens to identify ligands that modulate the activity of a receptor protein, and they also offer structural information about conformational changes upon ligand binding (Fischetti et al., 2004). The sample requirements range between 200 and 500 μL, with protein concentrations of 5–10 mg/mL. Higher concentrations generally result in data with a higher signal/noise ratio. This technique is more sensitive to protein-ligand size ratios. Changes for ligands <2% of the total protein-ligand Mr are difficult to detect by WAXS (e.g. 700 D ligand for a receptor target protein of 35 kD; Fischetti et al., 2004).

CONCLUSION

Decoding and quantifying protein-ligand interactions and protein-protein interactions is at the core of dissecting the biochemical mechanisms that regulate cellular processes (Dupeux et al., 2011; Hohmann et al., 2018a). The aim to seek an optimal technique to measure molecular interactions has challenged scientists to develop and engineer new ways to accurately detect and quantify protein-ligand and protein-protein interactions. In this review, we sought to provide the reader with an overview of state-of-the-art in vitro methods, their advantages, limitations, and considerations that should be taken into account when performing the experiments. In our analysis, we highlight the importance of mandatory quality-control check of protein samples and the value of using a combination of orthogonal techniques to uncover the different parameters and molecular mechanisms that drive the formation of signaling complexes. Currently, the methods described are restricted to quantify the contribution of one-on-one interactors in a particular condition. Hopefully, future methods will accommodate the detection of multiple interactor partners/competitors to dissect multimeric signaling complexes (see Outstanding Questions). Similarly, the array of in vitro methods for studying integral-membrane receptor-ligand interactions is rather limited due to the necessity of working with soluble parts in the best of cases (see Outstanding Questions). New approaches are addressing this issue using protein engineering to insert stabilizing mutations that allow successful solubilization of the integral-membrane receptor (IMR) in detergent micelles, to be used in biochemical ligand assays (Scott et al., 2013; Rawlings, 2016). Even though in vitro characterization is a very powerful approach for dissecting biological interactions, it need to be contrasted with in vivo data, since other molecules, dynamic environmental conditions, or members of the signaling complex may contribute to binding properties and affinities. We look forward to future technological developments that will help us to unravel complex signaling matrixes.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to researchers whose work has not been cited due to space limitations.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the University of Lausanne, the European Research Council (ERC; grant no. 716358 to J.S.), the Swiss National Science Foundation (Schweizerische Nationalfonds; grant no. 31003A_173101 to J.S.), and the Programme Fondation Philanthropique Famille Sandoz (J.S.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Adamczyk M, Moore JA, Shreder K(2002) Dual analyte detection using tandem flash luminescence. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 12: 395–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai N, Roder H, Dickson A, Karanicolas J(2019) Isothermal analysis of ThermoFluor data can readily provide quantitative binding affinities. Sci Rep 9: 2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker W, Bhattiprolu KC, Gubensäk N, Zangger K(2018) Investigating protein-ligand interactions by solution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. ChemPhysChem 19: 895–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogner M, Ludewig U(2007) Visualization of arginine influx into plant cells using a specific FRET-sensor. J Fluoresc 17: 350–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butenko MA, Wildhagen M, Albert M, Jehle A, Kalbacher H, Aalen RB, Felix G(2014) Tools and strategies to match peptide-ligand receptor pairs. Plant Cell 26: 1838–1847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund DB, Deupree JD, Toews ML(2004) Radioligand-binding methods for membrane preparations and intact cells. Methods Mol Biol 259: 1–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady WG.(1964) Piezoelectricity: An Introduction to the Theory and Applications of Electromechanical Phenomena to Crystals Vol Vol. 1 Dover Publications, Mineola, NY [Google Scholar]

- Cala O, Guillière F, Krimm I(2014) NMR-based analysis of protein-ligand interactions. Anal Bioanal Chem 406: 943–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-Y, Ho S-S, Kuo T-Y, Hsieh H-L, Cheng Y-S(2017) Structural basis of jasmonate-amido synthetase FIN219 in complex with glutathione S-transferase FIP1 during the JA signal regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: E1815–E1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Masiewicz P, Perez K, Hennig J (2019) Structure-based screening of binding affinities via small-angle x-ray scattering. bioRxiv 715193 doi: 10.1101/715193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Mills JD, Periasamy A(2003) Protein localization in living cells and tissues using FRET and FLIM. Differentiation 71: 528–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiliveri SC, Aute R, Rai U, Deshmukh MV(2017) DRB4 dsRBD1 drives dsRNA recognition in Arabidopsis thaliana tasi/siRNA pathway. Nucleic Acids Res 45: 8551–8563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HW, Manohar M, Manosalva P, Tian M, Moreau M, Klessig DF(2016) Activation of plant innate immunity by extracellular high mobility Group Box 3 and its inhibition by salicylic acid. PLoS Pathog 12: e1005518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Tanaka K, Cao Y, Qi Y, Qiu J, Liang Y, Lee SY, Stacey G(2014) Identification of a plant receptor for extracellular ATP. Science 343: 290–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JL, Hansen JC(1999) Analytical ultracentrifugation as a contemporary biomolecular research tool. J Biomol Tech 10: 163–176 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JL, Lary JW, P Moody T, Laue TM(2008) Analytical ultracentrifugation: sedimentation velocity and sedimentation equilibrium. Methods Cell Biol 84: 143–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concepcion J, Witte K, Wartchow C, Choo S, Yao D, Persson H, Wei J, Li P, Heidecker B, Ma W, et al. (2009) Label-free detection of biomolecular interactions using BioLayer interferometry for kinetic characterization. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen 12: 791–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto D, Zipfel C(2016) Regulation of pattern recognition receptor signalling in plants. Nat Rev Immunol 16: 537–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie J.(1889) Quartz piézo-électrique. Ann Chim Phys 17: 392 [Google Scholar]

- Deuschle K, Chaudhuri B, Okumoto S, Lager I, Lalonde S, Frommer WB(2006) Rapid metabolism of glucose detected with FRET glucose nanosensors in epidermal cells and intact roots of Arabidopsis RNA-silencing mutants. Plant Cell 18: 2314–2325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Sun T, Ao K, Peng Y, Zhang Y, Li X, Zhang Y(2018) Opposite roles of salicylic acid receptors NPR1 and NPR3/NPR4 in transcriptional regulation of plant immunity. Cell 173: 1454–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MC.(2008) Quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring: Enabling real-time characterization of biological materials and their interactions. J Biomol Tech 19: 151–158 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doblas VG, Smakowska-Luzan E, Fujita S, Alassimone J, Barberon M, Madalinski M, Belkhadir Y, Geldner N(2017) Root diffusion barrier control by a vasculature-derived peptide binding to the SGN3 receptor. Science 355: 280–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Li Y, Xia Y-L, Ai S-M, Liang J, Sang P, Ji X-L, Liu S-Q(2016) Insights into protein-ligand interactions: Mechanisms, models, and methods. Int J Mol Sci 17: E144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff MR, Grubbs J, Howell EE(2011) Isothermal titration calorimetry for measuring macromolecule-ligand affinity. J Vis Exp 2011: 2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupeux F, Santiago J, Betz K, Twycross J, Park S-Y, Rodriguez L, Gonzalez-Guzman M, Jensen MR, Krasnogor N, Blackledge M, et al. (2011) A thermodynamic switch modulates abscisic acid receptor sensitivity. EMBO J 30: 4171–4184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer RJ.(2016) Applications of isothermal titration calorimetry—The research and technical developments from 2011 to 2015. J Mol Recognit 29: 504–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischetti RF, Rodi DJ, Gore DB, Makowski L(2004) Wide-angle x-ray solution scattering as a probe of ligand-induced conformational changes in proteins. Chem Biol 11: 1431–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks WT, Linden AH, Kunert B, van Rossum B-J, Oschkinat H(2012) Solid-state magic-angle spinning NMR of membrane proteins and protein-ligand interactions. Eur J Cell Biol 91: 340–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiburger L, Auclair K, Mittermaier A(2015) Global ITC fitting methods in studies of protein allostery. Methods 76: 149–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire E, Mayorga OL, Straume M(1990) Isothermal titration calorimetry. Anal Chem 62: 950A–959A [Google Scholar]

- Freyer MW, Lewis EA(2008) Isothermal titration calorimetry: Experimental design, data analysis, and probing macromolecule/ligand binding and kinetic interactions. Methods Cell Biol 84: 79–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher ES, Hudgens JW(2016) Mapping protein-ligand interactions with proteolytic fragmentation, hydrogen/deuterium exchange-mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol 566: 357–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghalali A, Rice JM, Kusztos A, Jernigan FE, Zetter BR, Rogers MS(2019) Developing a novel FRET assay, targeting the binding between Antizyme-AZIN. Sci Rep 9: 4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöckner N, zur Oven-Krockhaus S, Wackenhut F, Burmeister M, Wanke F, Holzwart E, Meixner AJ, Wolf S, Harter K (2019) Three-fluorophore FRET-FLIM enables the study of trimeric protein interactions and complex formation with nanoscale resolution in living plant cells. bioRxiv 722124 doi: 10.1101/722124 [Google Scholar]

- Goldflam M, Tarragó T, Gairí M, Giralt E(2012) NMR studies of protein-ligand interactions. Methods Mol Biol 831: 233–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonneau M, Desprez T, Martin M, Doblas VG, Bacete L, Miart F, Sormani R, Hématy K, Renou J, Landrein B, et al. (2018) Receptor kinase THESEUS1 is a rapid alkalinization factor 34 receptor in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 28: 2452–2458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazak O, Brandt B, Cattaneo P, Santiago J, Rodriguez-Villalon A, Hothorn M, Hardtke CS(2017) Perception of root-active CLE peptides requires CORYNE function in the phloem vasculature. EMBO Rep 18: 1367–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth A, Calderón Villalobos LIA(2016) Radioligand binding assays for determining dissociation constants of phytohormone receptors. Methods Mol Biol 1450: 23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoare SRJ, Usdin TB(1999) Quantitative cell membrane-based radioligand binding assays for parathyroid hormone receptors. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 41: 83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann U, Lau K, Hothorn M(2017) The structural basis of ligand perception and signal activation by receptor kinases. Annu Rev Plant Biol 68: 109–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann U, Nicolet J, Moretti A, Hothorn LA, Hothorn M(2018a) The SERK3 elongated allele defines a role for BIR ectodomains in brassinosteroid signalling. Nat Plants 4: 345–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann U, Santiago J, Nicolet J, Olsson V, Spiga FM, Hothorn LA, Butenko MA, Hothorn M(2018b) Mechanistic basis for the activation of plant membrane receptor kinases by SERK-family coreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: 3488–3493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett GJ, Minton AP, Rivas G(2006) Analytical ultracentrifugation for the study of protein association and assembly. Curr Opin Chem Biol 10: 430–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutsell SQ, Kimple RJ, Siderovski DP, Willard FS, Kimple AJ(2010) High-affinity immobilization of proteins using biotin- and GST-based coupling strategies. Methods Mol Biol 627: 75–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indyk L, Fisher HF(1998) Theoretical aspects of isothermal titration calorimetry. Methods Enzymol 295: 350–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain P, Arora D, Bhatla SC(2016) Surface plasmon resonance based recent advances in understanding plant development and related processes. Biochem Anal Biochem 5: 1000300 [Google Scholar]

- Jerabek-Willemsen M, André T, Wanner R, Roth HM, Duhr S, Baaske P, Breitsprecher D(2014) MicroScale thermophoresis: Interaction analysis and beyond. J Mol Struct 1077: 101–113 [Google Scholar]

- Jerabek-Willemsen M, Wienken CJ, Braun D, Baaske P, Duhr S(2011) Molecular interaction studies using microscale thermophoresis. Assay Drug Dev Technol 9: 342–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CN, Gorbet GE, Ramsower H, Urquidi J, Brancaleon L, Demeler B(2018) Multi-wavelength analytical ultracentrifugation of human serum albumin complexed with porphyrin. Eur Biophys J 47: 789–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong LAA, Uges DRA, Franke JP, Bischoff R(2005) Receptor-ligand binding assays: Technologies and applications. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 829: 1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joss UR, Towbin H(1994) Acridinium ester labelled cytokines: Receptor binding studies with human interleukin-1α, interleukin-1β and interferon-γ. J Biolumin Chemilumin 9: 21–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapusta P, Erdmann R, Ortmann U, Wahl M(2003) Time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy measurements made simple. J Fluoresc 13: 179–183 [Google Scholar]

- Kikhney AG, Svergun DI(2015) A practical guide to small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) of flexible and intrinsically disordered proteins. FEBS Lett 589(19 Pt A): 2570–2577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozma P, Hamori A, Cottier K, Kurunczi S, Horvath R(2009) Grating coupled interferometry for optical sensing. Appl Phys B 97: 5–8 [Google Scholar]

- Kozma P, Hámori A, Kurunczi S, Cottier K, Horvath R(2011) Grating coupled optical waveguide interferometer for label-free biosensing. Sens Actuators B Chem 155: 446–450 [Google Scholar]

- Krainer G, Keller S(2015) Single-experiment displacement assay for quantifying high-affinity binding by isothermal titration calorimetry. Methods 76: 116–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Mazumder M, Gupta N, Chattopadhyay S, Gourinath S(2016) Crystal structure of Arabidopsis thaliana calmodulin7 and insight into its mode of DNA binding. FEBS Lett 590: 3029–3039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutschera A, Dawid C, Gisch N, Schmid C, Raasch L, Gerster T, Schäffer M, Smakowska-Luzan E, Belkhadir Y, Vlot AC, et al. (2019) Bacterial medium-chain 3-hydroxy fatty acid metabolites trigger immunity in Arabidopsis plants. Science 364: 178–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyo M, Ohtsuka K, Okamoto E, Inamori K(2009) High-throughput SPR biosensor. Methods Mol Biol 577: 227–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz JR.(2006) Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy 3rd ed Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- Laricchia-Robbio L, Revoltella RP(2004) Comparison between the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and the quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) method in a structural analysis of human endothelin-1. Biosens Bioelectron 19: 1753–1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Hnilova M, Maes M, Lin Y-CL, Putarjunan A, Han S-K, Avila J, Torii KU(2015) Competitive binding of antagonistic peptides fine-tunes stomatal patterning. Nature 522: 439–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Zhang L, Han Z, Yang X, Liu W, Li E, Chang J, Qi Y, Shpak ED, Chai J(2017) A receptor-like protein acts as a specificity switch for the regulation of stomatal development. Genes Dev 31: 927–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Liu Z, Song C, Hu Y, Han Z, She J, Fan F, Wang J, Jin C, Chang J, Zhou JM, Chai J(2012) Chitin-induced dimerization activates a plant immune receptor. Science 336: 1160–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Jaiswal A, Poggi MA, Wilson WD(2011) Surface llasmon resonance and quartz crystal microbalance methods for detection of molecular interactions In Wang B, and Anslyn EV, eds, Chemosensors: Principles, Strategies and Applications. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, pp 329–344 [Google Scholar]

- Lo M-C, Aulabaugh A, Jin G, Cowling R, Bard J, Malamas M, Ellestad G(2004) Evaluation of fluorescence-based thermal shift assays for hit identification in drug discovery. Anal Biochem 332: 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Y, Stahl Y, Weidtkamp-Peters S, Smet W, Du Y, Gadella TWJ Jr., Goedhart J, Scheres B, Blilou I(2018) Optimizing FRET-FLIM labeling conditions to detect nuclear protein interactions at native expression levels in living Arabidopsis roots. Front Plant Sci 9: 639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Orts L, Hohmann U, Zhu J, Hothorn M(2019) Molecular characterization of CHAD domains as inorganic polyphosphate-binding modules. Life Sci Alliance 2: e201900385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukosz W.(1991) Principles and sensitivities of integrated optical and surface plasmon sensors for direct affinity sensing and immunosensing. Biosens Bioelectron 6: 215–225 [Google Scholar]

- Lumba S, Cutler S, McCourt P(2010) Plant nuclear hormone receptors: A role for small molecules in protein-protein interactions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26: 445–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Liu Y, Bai B, Han Z, Tang J, Zhang H, Yaghmaiean H, Zhang Y, Chai J(2017) Structural basis for BIR1-mediated negative regulation of plant immunity. Cell Res 27: 1521–1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson AO, Szekrenyi A, Joosten H-J, Finnigan J, Charnock S, Fessner W-D(2019) nanoDSF as screening tool for enzyme libraries and biotechnology development. FEBS J 286: 184–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire JJ, Kuc RE, Davenport AP(2012) Radioligand binding assays and their analysis In Davenport AP, ed, Receptor Binding Techniques. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp 31–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SF, Tatham MH, Hay RT, Samuel IDW(2008) Quantitative analysis of multi-protein interactions using FRET: Application to the SUMO pathway. Protein Sci 17: 777–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson GR, Burke JE, Ahn NG, Anand GS, Borchers C, Brier S, Bou-Assaf GM, Engen JR, Englander SW, Faber J, et al. (2019) Recommendations for performing, interpreting and reporting hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) experiments. Nat Methods 16: 595–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson GR, Jenkins ML, Burke JE(2017) An overview of hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) in drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov 12: 981–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matulis D, Kranz JK, Salemme FR, Todd MJ(2005) Thermodynamic stability of carbonic anhydrase: Measurements of binding affinity and stoichiometry using ThermoFluor. Biochemistry 44: 5258–5266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard JA, Lindquist NC, Sutherland JN, Lesuffleur A, Warrington AE, Rodriguez M, Oh S-H(2009) Surface plasmon resonance for high-throughput ligand screening of membrane-bound proteins. Biotechnol J 4: 1542–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecchia MA, Santos-Fernandez G, Duss NN, Somoza SC, Boisson-Dernier A, Gagliardini V, Martínez-Bernardini A, Fabrice TN, Ringli C, Muschietti JP, et al. (2017) RALF4/19 peptides interact with LRX proteins to control pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis. Science 358: 1600–1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau MJJ, Schaeffer PM(2013) Dissecting the salt dependence of the Tus-Ter protein-DNA complexes by high-throughput differential scanning fluorimetry of a GFP-tagged Tus. Mol Biosyst 9: 3146–3154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mork-Jansson AE, Eichacker LA(2018) Characterization of chlorophyll binding to LIL3. PLoS One 13: e0192228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou S, Zhang X, Han Z, Wang J, Gong X, Chai J(2017) CLE42 binding induces PXL2 interaction with SERK2. Protein Cell 8: 612–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussu S, Santiago J(2019) Structural biology of cell surface receptor-ligand interactions. Curr Opin Plant Biol 52: 38–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyroud E, Reymond MCA, Hamès C, Parcy F, Scutt CP(2009) The analysis of entire gene promoters by surface plasmon resonance. Plant J 59: 851–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P, Banerjee S, Wheeler A, Ratliff LA, Irigoyen S, Garcia LR, Lockless SW, Versaw WK(2015) Live imaging of inorganic phosphate in plants with cellular and subcellular resolution. Plant Physiol 167: 628–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PN, Tossounian M-A, Kovacs DS, Thu TT, Stijlemans B, Vertommen D, Pauwels J, Gevaert K, Angenon G, Messens J, et al. (2020) Dehydrin ERD14 activates glutathione transferase Phi9 in Arabidopsis thaliana under osmotic stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 1864: 129506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura T, Hattori O(1980) Determination of micromolar concentrations of cyanide in solution with a piezoelectric detector. Anal Chim Acta 115: 323–326 [Google Scholar]

- Offenbacher AR, Iavarone AT, Klinman JP(2018) Hydrogen-deuterium exchange reveals long-range dynamical allostery in soybean lipoxygenase. J Biol Chem 293: 1138–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Shinohara H, Sakagami Y, Matsubayashi Y(2008) Arabidopsis CLV3 peptide directly binds CLV1 ectodomain. Science 319: 294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda S, Fujita S, Moretti A, Hohmann U, Doblas VG, Ma Y, Pfister A, Brandt B, Geldner N, Hothorn M(2020) Molecular mechanism for the recognition of sequence-divergent CIF peptides by the plant receptor kinases GSO1/SGN3 and GSO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117: 2693–2703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaru A, Bala C, Jaffrezic-Renault N, Aboul-Enein HY(2015) Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors in pharmaceutical analysis. Crit Rev Anal Chem 45: 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patko D, Cottier K, Hamori A, Horvath R(2012) Single beam grating coupled interferometry: High resolution miniaturized label-free sensor for plate based parallel screening. Opt Express 20: 23162–23173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RL.(2017) Strategies using Bio-Layer interferometry biosensor technology for vaccine research and development. Biosensors (Basel) 7: E49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putarjunan A, Ruble J, Srivastava A, Zhao C, Rychel AL, Hofstetter AK, Tang X, Zhu J-K, Tama F, Zheng N, et al. (2019) Bipartite anchoring of SCREAM enforces stomatal initiation by coupling MAP kinases to SPEECHLESS. Nat Plants 5: 742–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan M, Bjorkman PJ(1995) BIAcore: A microchip-based system for analyzing the formation of macromolecular complexes. Structure 3: 331–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings AE.(2016) Membrane proteins: Always an insoluble problem? Biochem Soc Trans 44: 790–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roda A, Guardigli M, Michelini E, Mirasoli M, Pasini P(2003) Peer reviewed: Analytical bioluminescence and chemiluminescence. Anal Chem 75: 462A–470A [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Dutta A, Roy D, Ganguly P, Ghosh R, Kar RK, Bhunia A, Mukhopadhyay J, Chaudhuri S(2016) Deciphering the role of the AT-rich interaction domain and the HMG-box domain of ARID-HMG proteins of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 92: 371–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer CA.(2006) Probing protein folding and conformational transitions with fluorescence. Chem Rev 106: 1769–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago J, Brandt B, Wildhagen M, Hohmann U, Hothorn LA, Butenko MA, Hothorn M(2016) Mechanistic insight into a peptide hormone signaling complex mediating floral organ abscission. eLife 5: e15075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago J, Rodrigues A, Saez A, Rubio S, Antoni R, Dupeux F, Park S-Y, Márquez JA, Cutler SR, Rodriguez PL(2009) Modulation of drought resistance by the abscisic acid receptor PYL5 through inhibition of clade A PP2Cs. Plant J 60: 575–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller GE, Bleecker AB(1995) Ethylene-binding sites generated in yeast expressing the Arabidopsis ETR1 gene. Science 270: 1809–1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Kummer L, Tremmel D, Plückthun A(2013) Stabilizing membrane proteins through protein engineering. Curr Opin Chem Biol 17: 427–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel SAI, Wienken CJ, Geissler S, Jerabek-Willemsen M, Duhr S, Reiter A, Trauner D, Braun D, Baaske P(2012) Label-free microscale thermophoresis discriminates sites and affinity of protein-ligand binding. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 51: 10656–10659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto Y, Yasui R, Kameoka H, Tamiru M, Cao M, Terauchi R, Sakurada A, Hirano R, Kisugi T, Hanada A, et al. (2019) Strigolactone perception and deactivation by a hydrolase receptor DWARF14. Nat Commun 10: 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Rodgers VGJ, Schultz JS, Liao J(2012) Protein interaction affinity determination by quantitative FRET technology. Biotechnol Bioeng 109: 2875–2883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soon F-F, Suino-Powell KM, Li J, Yong E-L, Xu HE, Melcher K(2012) Abscisic acid signaling: Thermal stability shift assays as tool to analyze hormone perception and signal transduction. PLoS One 7: e47857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka Y, Nagumo K, Azizah IN, Oura S, Iwahashi M, Kato N, Ueda M(2019) A comprehensive in vitro fluorescence anisotropy assay system for screening ligands of the jasmonate COI1-JAZ co-receptor in plants. J Biol Chem 294: 5074–5081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu T, Drăguşanu M, Petre B-A, Rempel DL, Przybylski M, Gross ML(2010) Protein-peptide affinity determination using an H/D exchange dilution strategy: Application to antigen-antibody interactions. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 21: 1660–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallone R, La Verde V, D’Onofrio M, Giorgetti A, Dominici P, Astegno A(2016) Metal binding affinity and structural properties of calmodulin-like protein 14 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Protein Sci 25: 1461–1471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiksina S, Kopanchuk S, Rinken A(2014) Budded baculoviruses as a tool for a homogeneous fluorescence anisotropy-based assay of ligand binding to G protein-coupled receptors: The case of melanocortin 4 receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1838: 372–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waadt R, Hitomi K, Nishimura N, Hitomi C, Adams SR, Getzoff ED, Schroeder JI(2014) FRET-based reporters for the direct visualization of abscisic acid concentration changes and distribution in Arabidopsis. eLife 3: e01739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Zhou M, Zhang X, Yao J, Zhang Y, Mou Z(2017) A lectin receptor kinase as a potential sensor for extracellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide in Arabidopsis thaliana. eLife 6: e25474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Loo JFC, Chen J, Yam Y, Chen S-C, He H, Kong SK, Ho HP(2019a) Recent advances in surface plasmon resonance imaging sensors. Sensors (Basel) 19: E1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zhu T, Fan E, Lu N, Ouyang F, Wang N, Yang G, Kong L, Qu G, Zhang S, et al. (2019b) Potential function of CbuSPL and gene encoding its interacting protein during flowering in Catalpa bungei. bioRxiv 803122 doi: 10.1101/803122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wartchow CA, Podlaski F, Li S, Rowan K, Zhang X, Mark D, Huang K-S(2011) Biosensor-based small molecule fragment screening with biolayer interferometry. J Comput Aided Mol Des 25: 669–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks I, Beheshti I, McCapra F, Campbell AK, Woodhead JS(1983) Acridinium esters as high-specific-activity labels in immunoassay. Clin Chem 29: 1474–1479 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild R, Gerasimaite R, Jung J-Y, Truffault V, Pavlovic I, Schmidt A, Saiardi A, Jessen HJ, Poirier Y, Hothorn M, et al. (2016) Control of eukaryotic phosphate homeostasis by inositol polyphosphate sensor domains. Science 352: 986–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]