Abstract

Introduction:

Breast cancer is the most common neoplasia of women from all over the world especially women from Colombia. 5%10% of all cases are caused by hereditary factors, 25% of those cases have mutations in the BRCA1/BRCA2 genes.

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to identify the mutations associated with the risk of familial breast and/or ovarian cancer in a population of Colombian pacific.

Methods:

58 high-risk breast and/or ovarian cancer families and 20 controls were screened for germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, by Single Strand Conformation Polymorphism (SSCP) and sequencing.

Results:

Four families (6.9%) were found to carry BRCA1 mutations and eight families (13.8%) had mutations in BRCA2. In BRCA1, we found three Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS), of which we concluded, using in silico tools, that c.8112C>G and c.3119G>A (p.Ser1040Asn) are probably deleterious, and c.3083G>A (p.Arg1028His) is probably neutral. In BRCA2, we found three variants of uncertain significance: two were previously described and one novel mutation. Using in silico analysis, we concluded that c.865A>G (p.Asn289Asp) and c.6427T>C (p.Ser2143Pro) are probably deleterious and c.125A>G (p.Tyr42Cys) is probably neutral. Only one of them has previously been reported in Colombia. We also identified 13 polymorphisms (4 in BRCA1 and 9 in BRCA2), two of them are associated with a moderate increase in breast cancer risk (BRCA2 c.1114A>C and c.875566T>C).

Conclusion:

According to our results, the Colombian pacific population presents diverse mutational spectrum for BRCA genes that differs from the findings in other regions in the country.

Keywords: Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome, BRCA1, BRCA2, Germ-line mutations, Colombia

Resumen

Introducción:

El cáncer de mama es la neoplasia más común en mujeres de todo el mundo, y, también de Colombia. 5% a 10% de todos los casos son causados por factores hereditarios; 25% de estos casos tienen mutaciones en los genes BRCA1/BRCA2.

Objetivo:

El propósito de este estudio fue el de identificar mutaciones asociadas con riesgo de cáncer de mama y/u ovario familiar en pacientes del pacífico colombiano.

Métodos:

Fueron revisados para mutaciones en BRCA1 y BRCA2 de línea germinal mediante SSCP y secuenciación 58 familias de alto riesgo para cáncer de mama y/u ovario y 20 controles

Resultados:

cuatro familias (6.9%) presentaron mutaciones en BRCA1 y ocho familias (13.8%) en BRCA2. En BRCA1, encontramos tres variantes de significado clínico desconocido (VUS), de las cuales concluimos, usando herramientas bioinformáticas, que c.8112C>G y c.3119G>A (p.Ser1040Asn) son probablemente deletéreas, y c.3083G>A (p.Arg1028His) es probablemente neutral. En BRCA2, encontramos tres VUS: una mutación nueva y dos previamente descritas, usando análisis bioinformáticos, concluimos que c.865A>G (p.Asn289Asp) y c.6427T>C (p.Ser2143Pro) son probablemente deletéreas y c.125A>G (p.Tyr42Cys) es probablemente neutral. Solo una de ellas ha sido reportada previamente en Colombia. También identificamos 13 polimorfismos (4 en BRCA1 y 9 en BRCA2), dos de ellos asociados con un moderado incremento del riesgo para cáncer de mama (BRCA2 c.1114A>C and c.875566T>C).

Conclusión:

de acuerdo con nuestros resultados, la población del suroccidente colombiano presenta un espectro mutacional diverso para los genes BRCA que difiere de lo encontrado en otras regiones del país.

Palabras clave: Síndrome de Cáncer de Mama y Ovario Hereditario, BRCA1, BRCA2, Mutación de Línea Germinal, Colombia

Remark

| 1) Why was this study done? |

| The prevalence and type of BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutations varies considerably, among diverse ethnic groups and geographical areas. The population from Colombian pacific have a special genomic background with a high degree population admixture between Amerindians, Afro-descendants and Europeans. Data on the contribution of germline BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations to breast cancer in the Colombian population is scarce. The purpose of this study was to identify the mutations associated with the risk of familial breast and/or ovarian cancer in a population of Colombian pacific. |

| 2) What did the researchers do and find? |

| In this study, a mutational screening was performed for the entire coding region and exon-intron boundaries of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in high-risk Colombian families selected based on their family history of breast and ovarian cancer. 58 high-risk breast and/or ovarian cancer families and 20 controls were screened for germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, by Single Strand Conformation Polymorphism (SSCP) and sequencing. Four families were found to carry BRCA1 mutations and eight families had mutations in BRCA2. In BRCA1, we found three Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS), of which we concluded, using in silico tools, that c.8112C>G and c.3119G>A (p.Ser1040Asn) are probably deleterious, and c.3083G>A (p.Arg1028His) is probably neutral. In BRCA2, we found three variants of uncertain significance, using in silico analysis, we concluded that c.865A>G (p.Asn289Asp) and c.6427T>C (p.Ser2143Pro) are probably deleterious and c.125A>G (p.Tyr42Cys) is probably neutral. We also identified 13 polymorphisms (4 in BRCA1 and 9 in BRCA2), two of them are associated with a moderate increase in breast cancer risk (BRCA2 c.1114A>C and c.875566T>C). |

| 3) What do these findings mean? |

| The Colombian pacific population presents diverse mutational spectrum for BRCA genes that differs from the findings in other regions in the country. Therefore, the extrapolation of results from one region to the rest of the Colombian population is risky; these findings indicate that the Colombian population has a heterogeneous spectrum of BRCA mutations, so it is of utmost importance to generate studies where the different regions of the country are represented, in order to make a real approach to the Colombian mutational spectrum. |

Introduction

Breast Cancer (BC) is the most common type of cancer among women, with an estimated value of 1.67 million new cancer cases diagnosed in the year 2012 1 . In Colombia, this neoplasia is the main cause of cancer death in women 1 and for Santiago de Cali, which is the main urban center from Southwest Colombia, breast cancer occupies the first place in incidence and mortality rates in the female population 2 .

Of all cases of breast cancer, about 5%-10% have a strong inherited component, of which 25% is explained by germline mutations in the high penetrance breast cancer predisposition genes, BRCA1 3 and BRCA2 4 . The risk of breast cancer for BRCA1 mutation carriers at age 70, has been estimated to be within the range of 40%-87% and for ovarian cancer 16%-68%; the corresponding risks for BRCA2 mutation carriers were estimated to be 40%-84% for breast cancer and 11%-27% for ovarian cancer 5 . The risk not explained by the high penetrance genes is due to moderate or low penetrance genes 6 , 7 , each having a small effect on breast cancer risk 8 .

The prevalence and type of BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutations varies considerably, among diverse ethnic groups and geographical areas. Population specific and recurrent mutations have been described among the Ashkenazi Jews, Iceland, The Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Germany, France, Spain, Canada, countries of eastern and southern Europe 9 and in Latin American populations, such as Chile, México, Brazil and Costa Rica 10 . Thousands of mutations found in BRCA genes, in families with breast/ovarian cancer are now described in several websites, such as The Breast Cancer Information Core (BIC) (https://research.nhgri.nih.gov/bic/), the Leiden Open Variation Database (LOVD) (http://www.lovd.nl/3.0/home) and The Universal Mutation Database (UMD) website (http://www.umd.be/).

The population from Colombian pacific have a special genomic background with a high degree population admixture between Amerindians, Afro-descendants and the Europeans 11 . Data on the contribution of germline BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations to breast cancer in the Colombian population is scarce; Torres et al. 12 , evaluated both genes using the SSCP (Single Strand Conformation Polymorphism), DHPLC (Denaturing High Performance Liquid Chromatography) and PTT (Protein Truncation Test) methodologies, and five deleterious mutations were reported in the central region of Colombia. The additional works conducted in the country have focused on searching for specific mutations 13 , 14 or evaluating mutational panels 15 , 16 . In this study, a mutational screening was performed for the entire coding region and exon-intron boundaries of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in a group of 58 high-risk Colombian families selected based on their family history of breast and ovarian cancer.

Material and Methods

High-risk BC/OC (Breast Cancer/ Ovarian Cancer) Families from the Colombian pacific were selected from the clinical files of four institutions that offer attention to the population of the pacific region. The selected families met, at least, one of the following criteria: at least three family members with breast or ovarian cancer at any age; two first degree family members affected, at least one, with breast cancer before 41 years of age or with ovarian cancer at any age; one breast cancer case diagnosed before 35 years or less; one ovarian cancer case diagnosed before age 32.

Pedigrees were constructed based on an index case; none of the families met the strict criteria for other known syndromes involving breast cancer, such as Li Fraumeni syndrome, ataxia telangiectasia, or Cowden disease.

Control population

The sample of healthy Colombian controls was recruited from the Cali community. DNA samples were taken from unrelated individuals, with no personal or familial history of cancer. These individuals were interviewed and informed as to the aims of the study. The control sample was matched by age, sex and socioeconomic status with respect to the cases.

The DNA samples of patients and controls were obtained after due considerations of ethical and legal requirements of the Universidad del Valle and the Colombian law for human research.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood lymphocytes and was obtained based on the method described by Miller et al 17 . The whole coding sequences and exon-intron boundaries of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes were amplified by the polymerase chain reaction, using the primers described by Barker 18 and by the BIC database. The fragments obtained were analyzed using SSCP 19 , 20 . Any fragment showing a mobility shift was directly sequenced in both directions. Sequencing was performed in an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, United States).

The obtained sequences were analyzed with the software ChromasPro version 1.7.6 (http://technelysium.com.au/wp/chromaspro/). The presence and localization of mutations were obtained by sequence alignment using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and the reference sequences used were for BRCA1: ADN NG_005905.2, ARN NM_007294.3 and for BRCA2: ADN NG_012772.3 and ARN MN_000059.3. Two types of nomenclature were used to verify if the detected variants were reported in the databases and in the literature; the traditional system of the BIC - database and the nomenclature from the Human Genetic Variation Society (HGVS) (http://www.hgvs.org/).

Computational analysis

In order to determine the possible effects of sequence alterations of unknown clinical significance, the following prediction software were run for missense substitutions: AlignGVGD (http://agvgd.iarc.fr/index.php), PANTHER (http://pantherdb.org/), PolyPhen2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), SIFT (http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/), PROVEAN (http://provean.jcvi.org/index.php), MutPred (http://mutpred.mutdb.org/) and SNPs&GO (http://snps.biofold.org/snps-and-go/snps-and-go.html). Native alignments of each algorithm were used. For intronic mutations, splicing predictions were performed with: SSF, MaxEntScan, NNSplice and HSF algorithms, through the Alamut Visual Software v.2.7 (http://www.interactive-biosoftware.com/). Default thresholds were used for all the analyses. For the interpretation of the predictions of these five algorithms, we used the criteria by Thery et al 21 .

Results

A total of 72 index cases, belonging to 58 high-risk BC/OC families, were tested for BRCA1 and BRCA2. In the sample of selected families, 57% (33/58) had only BC; 24% (14/58) had both BC and OC, 7% (4/58) had BC and prostate cancer, and 12% (7/58) had breast, ovarian and prostate cancer. The clinical characteristics of the families included in this study are listed in Table 1. The diagnosis of cancer was certified by asking all index cases to provide their original pathology reports. The mean age of the patients at diagnosis was 41.7 years (ranging between 30-66 years). 46.6% of the patients were diagnosed before the age of 40, and 87.9 were diagnosed before the age of 50, 31 % of the families had three or more first degree relatives with either or both breast cancer and ovarian cancer.

Table 1. Selection criteria and clinical characteristics of the families included in this study .

| Selection Criteria | Family n (%) |

| ≥3 family members with breast cancer, at least one with ovarian cancer | 5 (8.6%) |

| ≥3 family members with breast cancer | 13 (22.4%) |

| 2 family members with breast cancer, at least one with ovarian cancer | 8 (13.8%) |

| 2 family members with breast cancer | 18 (31.0%) |

| 1 family member with breast cancer, at least one with ovarian cancer | 7 (12.1%) |

| Single affected individual with breast cancer < age 35 | 6 (10.4%) |

| Single affected individual with bilateral Ovarian cancer < age 31 | 1 (1.7%) |

| Total | 58 (100%) |

Germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations were found in 12 (20.6%) of the 58 families from the Colombian pacific region. We detected 6 variants of unknown clinical significance (3 in BRCA1 and 3 in BRCA2) (Table 2), only one of them has previously been reported in Colombia and 13 polymorphisms were also found (4 in BRCA1 and 9 in BRCA2) (Table 3).

Table 2. BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations detected in Colombian pacific high-risk breast/ovarian cancer families.

| E/I no. | cDNA | Protein change | Mutation Type | Family | Family Type | Index case status (age) | Family history (Br/Ov Ca) | Other cancers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | ||||||||

| I2 | c.81-12C>G | NA | Intronic | F43 | Br/Ov | BrCa (42 ) Ov Ca (42, 44) | 7 Br Ca 4 Ov Ca | Prostate, cervix, lung |

| E11 | c.3083G>A | p.Arg1028His | Missense | F52 F57 | Br Br | BrCa (45) BrCa (59) | 2 Br Ca 3 Br Ca | Column Prostate Gastric Lymphatic |

| E11 | c.3119G>A | p.Ser1040Asn | Missense | F56 | Br | BrCa (50) | 2 Br Ca | - |

| BRCA2 | ||||||||

| E3 | c.125A>G | p.Tyr42Cys | Missense | F44 | Br | BrCa (39) | 4 Br Ca | Lung, Stomach |

| E10 | c.865A>G | p.Asn289Asp | Missense | F9 | Br | BrCa (41) | 3 BrCa | - |

| F37 | Br | BrCa (47) | 4 BrCa | Lung, Colon | ||||

| F38 | Br/Ov | BrCa (49) | 1 BrCa 1 OvCa | Prostate Ovarian | ||||

| F49 | Br | BrCa (65) | 3 BrCa | - | ||||

| F52 | Br | BrCa (45) | 2 BrCa | Column | ||||

| F53 | Br | BrCa (51) | 2 BrCa | Colon | ||||

| E11 | c.6427T>C | p.Ser2143Pro | Missense | F34 | Br | BrCa (40) | 2 Br Ca | prostate, melanoma |

E/I= exon/intron, Br and BrCa: Breast Cancer, Ov and OvCa: Ovarian Cancer

Table 3. BRCA1 and BRCA2 polymorphisms detected in Colombian high-risk breast/ovarian cancer families.

| E/I no. | Nucleotide Change | Protein Change | dbSNP | Mutation Type | patients n=72 | controls n=20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | ||||||

| I7 | c.442-34C>T | NA | rs799923 | Intronic | 3 | 2 |

| E11 | c.2311T>C | p.Leu771= | rs16940 | S | 7 | 6 |

| E11 | c.3113A>G | p.Glu1038Gly | rs16941 | M | 32 | 12 |

| E16 | c.4837A>T | p.Ser1613Cys | rs1799966 | M | 48 | 12 |

| BRCA2 | ||||||

| E2 | c.-26G>A | NA | rs1799943 | 5’UTR | 23 | 2 |

| I4 | c.426-89T>C | NA | rs3783265 | Intronic | 2 | 0 |

| E10 | c.1114C>A | p.Asn372His | rs144848 | M | 25 | 2 |

| E11 | c.2971A>G | p.Asn991Asp | rs1799944 | M | 1 | 0 |

| E11 | c.3396A>G | p.Lys1132= | rs1801406 | S | 34 | 9 |

| E11 | c.6513C>G | p.Val2171= | rs206076 | S | 4 | 4 |

| I11 | c.6841+80_6841+83delTTAA | NA | rs3783265 | Intronic | 4 | 1 |

| I21 | c.8755-66T>C | NA | rs4942486 | Intronic | 40 | 9 |

| E22 | c.8851G>A | p.Ala2951Thr | rs11571769 | M | 23 | 6 |

E/I: exon/intron, S: synonymous, M: missense, NA: not applied, 5’UTR: 5’ untraslated region

Individuals without personal or familial breast cancer history were invited to participate as controls in the study. We recruited 20 control samples from the city of Cali (Colombia) who satisfied the inclusion criteria as stated in the methods.

BRCA1 Mutations

For BRCA1 we found three VUS, two corresponded to the missense type and one to the intronic type. The mutations found were identified in four families (6.9%) of our cohort, three of these families presented breast cancer and one family presented breast/ovarian cancer.

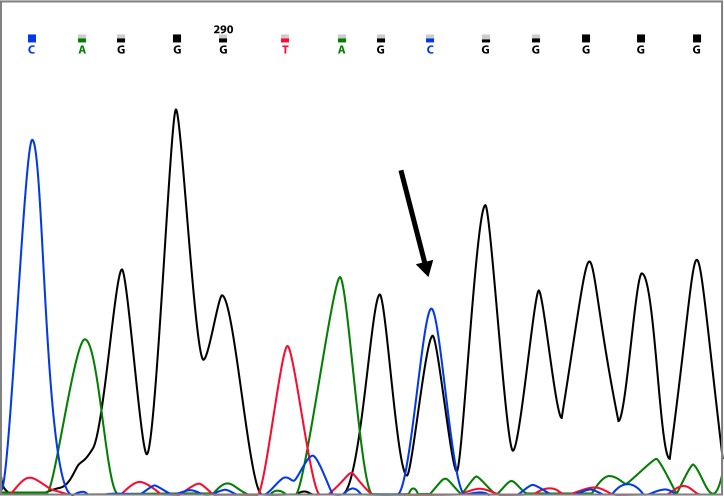

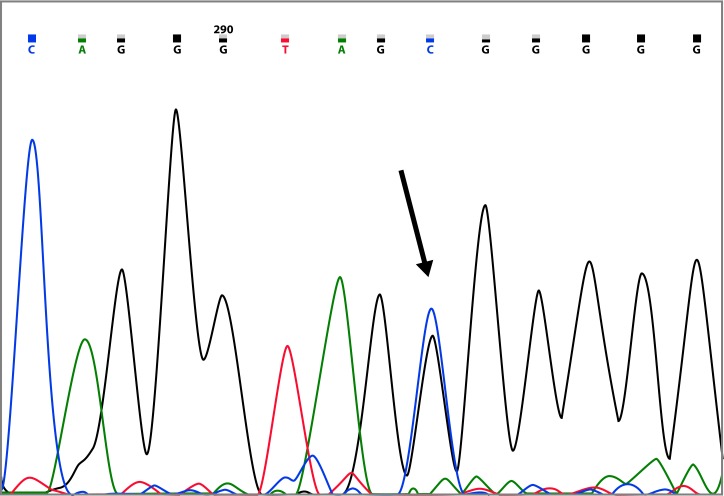

The mutation c.8112C>G, was found in three sisters, two with ovarian cancer (42 and 44 years, respectively) and one with breast cancer (42 years) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). This mutation has been reported 9 times in the BIC database, and it is found mainly in African American descendants. Till date, in South America, there are no previous reports for this mutation. Besides this intronic mutation, the three patients also presented the polymorphisms c.3113A>G and c.4837A>T in BRCA1.

Figure 1. Capillary sequencing chromatogram showing the BRCA1 c.8112C>G variant (marked with the arrow).

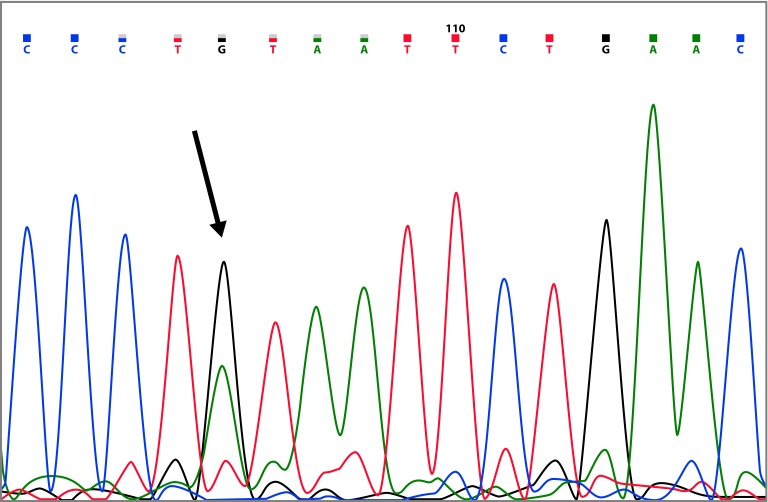

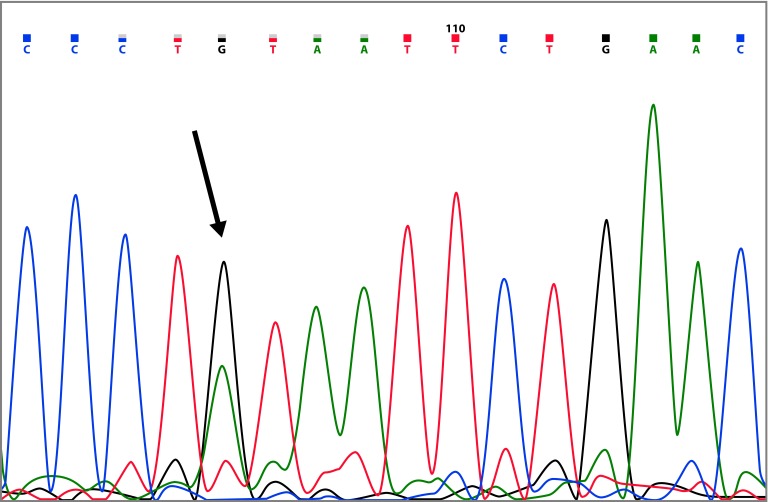

The mutation c.3083G>A (p.Arg1028His) was found in two families, the index cases were diagnosed at 45 and 59 years of age (Table 2 and Fig. 2). This mutation has been reported 13 times in the BIC database, 6 of these reports are from Latin America. Additionally, Arias-Blanco et al, reported this mutation in the Colombian population 22 .

Figure 2. Capillary sequencing chromatogram showing the BRCA1 c.3083G>A (p.Arg1028His) variant (marked with the arrow).

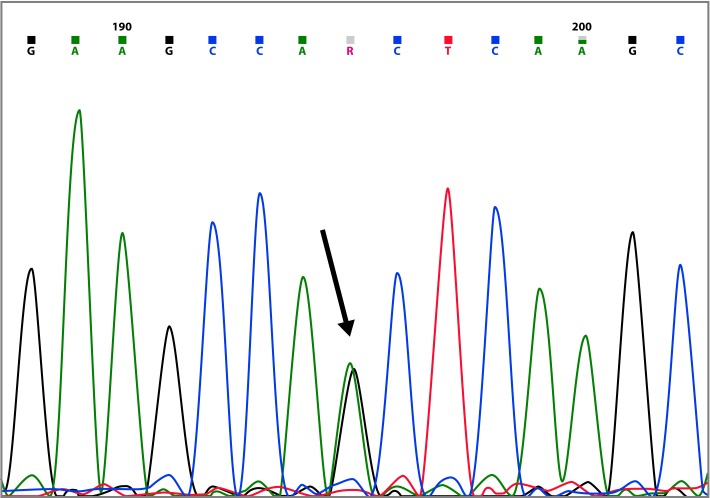

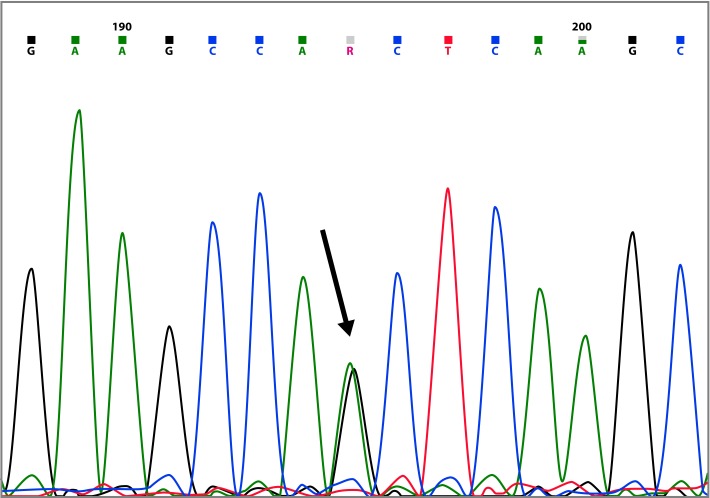

BRCA1 mutation c.3119G>A (p.Ser1040Asn), was found in a family with two cases of breast cancer (Table 2 and Fig. 3). In the BIC database, it has been reported 68 times, in Latin America it has been reported in Brazil 23 , Argentina 24 and Venezuela 25 . The missense mutations c.3119G>A and c.3083G>A, were always found together with the BRCA1 c.3113A>G polymorphism.

Figure 3. Capillary sequencing chromatogram showing the BRCA1 c.3119G>A (p.Ser1040Asn) variant (marked with the arrow).

BRCA2 Mutations

In BRCA2 we detected three missense variants of uncertain significance.

A new mutation not previously described was found in the BRCA2 gene, that is, the transition c.6427T>C that generates a serine to proline change (p.Ser2143Pro), this variant has neither been reported in the BIC databases, nor other databases consulted. Due to it being a missense mutation, we consider it as a VUS. This mutation was found in a family with two cases of breast cancer and one case of prostate cancer (Table 2). None of the controls presented the mutation.

The most prevalent mutation was c.865A>G, found in six (10.3%) of the families analyzed, in five of them, the age of diagnosis of index cases was between 41 and 51 years (Table 2). This mutation generates an asparagine for aspartate (p.Asn289Asp) change in the BRCA2 protein and has been reported 13 times in the BIC database, where it is classified as a VUS; however, this is the first report in South America. In this work, this mutation was found in every case accompanied by the BRCA2 c.8755-66T>C polymorphism.

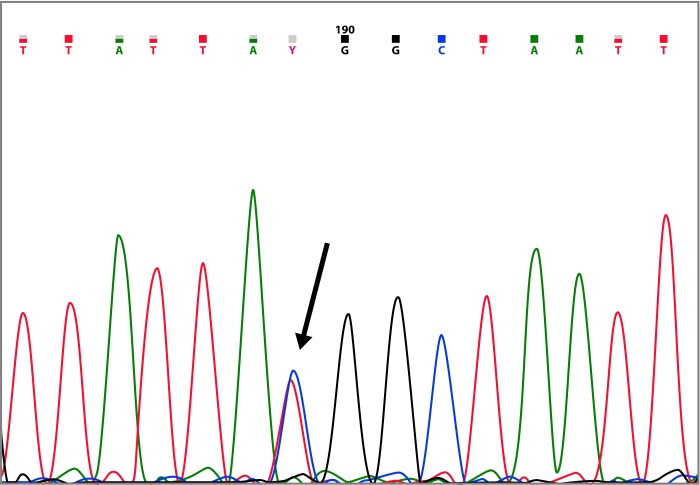

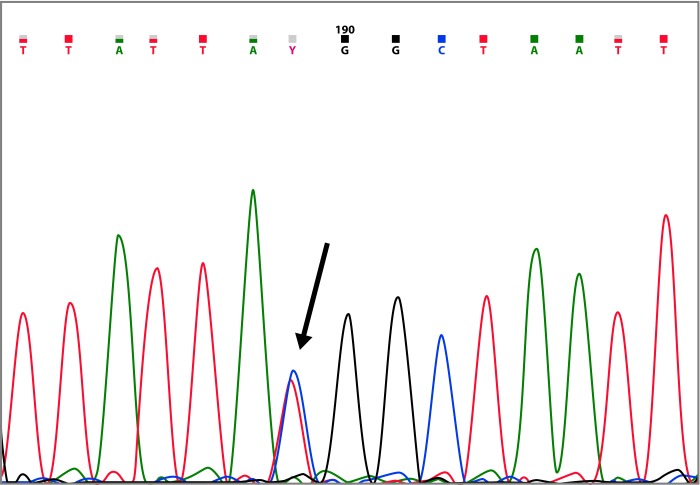

The mutation c.125A>G (p.Tyr42Cys) was identified in a patient diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 39, whose mother and two aunts also presented the neoplasia (Table 2 and Fig. 4). Of the 144 reports in the BIC database, two of them are from Latin America, additionally Ruiz-Flores et al. 26 , reported this mutation in the Mexican population.

Figure 4. Capillary sequencing chromatogram showing the BRCA2 c.125A>G (p.Tyr42Cys) variant (marked with the arrow).

None of the identified mutations were found in the control sample. All families with mutations in the BRCA genes, also presented polymorphisms. Regarding the found polymorphisms, it is important to note that the majority of these were detected in both, patients and controls, except for c.42689T>C and c.2971A>G, observed only in patients (Table 3).

BRCA2 c.6841+80_6841+83delTTAA has been reported as a VUS, 223 times in the BIC database. In this study, this alteration was found in homozygous state, taking into account the presence of this mutation in double doses, and being that, it was found in patients and controls, we concluded that this variant is of no clinical importance.

Analysis in silico

To predict the possible clinical relevance of VUS in BRCA1 and BRCA2, bioinformatics tools were used. Those in silico analysis were performed for five missense variants (two in the BRCA1 gene and three in BRCA2 gene) and for one intronic variant. From these results, the mutations c.8112C>G, c.3119G>A (p.Ser1040Asn) in BRCA1 and c.865A>G (p.Asn289Asp), c.6427T>C (p.Ser2143Pro) in BRCA2, were classified as probably deleterious and the mutations BRCA1 c.3083G>A (p.Arg1028His) and BRCA2 c.125A>G (p.Tyr42Cys), as probably neutrals. The details of the results of the in silico analysis, are shown in (Table 4 and 5).

Table 4. Results of bioinformatics analysis for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.

| Gene | cDNA | Protein Change | Align-GVGD | PANTHER (SubSPEC) | SIFT (Score) | PROVEAN (Score) | PolyPhen-2 (Prob.) | MutPred (Prob.) | SNP&GO (RI; EA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | c.3083G>A | p.Arg1028His | C0 | Neutral (-2.90) | Tolerated (0.23) | Neutral (0.12) | Benign (0) | Neutral (0.391) | Disease (4; 72%) |

| c.3119G>A | p.Ser1040Asn | C0 | Damaging (-3.46) | Tolerated (1) | Neutral (-1.69) | Probably Damaging (0.974) | Neutral (0.123) | Disease (7; 85%) | |

| BRCA2 | c.125A>G | p.Tyr42Cys | C0 | NA | Tolerated (0.113) | Neutral (-1.32) | Benign (0.09) | Neutral (0.243) | Disease (6; 78%) |

| c.865A>G | p.Asn289Asp | C0 | NA | Damaging (0.008) | Neutral (-1.14) | Benign (0.055) | Neutral (0.165) | Disease (9; 96%) | |

| c.6427T>C | p.Ser2143Pro | C0 | Damaging (-3.38) | Damaging (0.015) | Neutral (-1.22) | Probably Damaging (0.999) | Neutral (0.179) | Disease (8; 88%) |

Table 5. Results of bioinformatics analysis for BRCA1 intronic variant.

| Gene | cDNA | 5' or 3' score modification | (% variation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | c.81-12C>G | c.81N | SSF: | 70.09 → | - | -100.0% |

| c.81N | MaxEnt: | 7.05 → | 5.37 | -23.8% | ||

| c.81N | NNSPLICE: | 0.52 → | - | -100.0% | ||

| c.81N | GS: | 4.46 → | 3.40 | -23.8% | ||

| c.81N | HSF: | 77.26 → | 75.36 | -2.5% | ||

Discussion

A large number of mutations has been characterized in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Except for specific ethnic groups, there is no predominant mutation to account for the majority of cases of inherited breast cancer 27 . Despite the high prevalence of breast cancer in Colombia, data for this population is scarce 12 , 16 . An extrapolation of the results obtained in other populations is risky because the Colombian population is the result of a complex process of admixture 28 .

In this study, we examined 72 patients (58 families) with breast and/or ovarian familial cancer from the Southwestern region of Colombia, in order to identify the mutational spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. For the BRCA1 gene, we found 7 sequence variants, of which 3 have previously been classified as having unknown clinical significance, and 4 as polymorphisms. For BRCA2 gene, we found 12 variants, of which 2 have previously been classified as being of unknown clinical significance, one new mutation which has not been previously described, and 9 polymorphisms.

The most recurrent mutation in this study was BRCA2 c.865A>G (p.Asn289Asp). The analysis with SIFT classifies this mutation as being probably damaging (score: 0.008), just as SNP&GO (RI: 9) (Table 4). c.865A>G is located in a region of transcriptional activation 29 , and in the interaction region with the ALIX protein (amino acids 203300) 30 , this protein is part of the machinery that mediates the final membrane abscission event 31 . The possible role of BRCA2 in this process is controversial, but it is likely that recruits and delivers ALIX and other proteins, facilitating the completion of abscission 30 . Considering this evidence and the results from our in silico analysis, we suggest the p.Asn289Asp mutation as being probably deleterious.

Interestingly, p.Asn289Asp was found, in all cases, accompanied by polymorphism c.875566T>C, which has been associated with a 1.79fold increased risk of breast cancer (95% CI: 1.16-2.78, p= 0.009) 32 , therefore, it is likely that the convergence of p.Asn289Asp with polymorphism c.875566T>C further increases the risk of malfunction of the protein. Therefore, it is suggested, these variants as markers to consider in the diagnosis of the predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer in Colombian patients, taking into account the high frequency in which it was found, since 10.3% of the families exhibited this alteration.

Also, in the BRCA2 gene we report a novel mutation, the c.6427T>C (p.Ser2143Pro), this mutation was found in the index case, which presented BC at 40 years. For this missense mutation, PANTHER (3.38), SIFT (0.015) and Polyphen2 (score: 0.999) (Table 4) predicts that this variant is damaging, due to the Ser2143 being in a position highly conserved, additionally, SNP&GO predicts it as disease (RI 8), indicating a high probability of affecting the three dimensional structure of the protein, and probably its function. Therefore, we propose BRCA2 c.6427T>C as a variant to be considered in the diagnosis of predisposition to breast cancer and which, till date, can be considered as an exclusive variant from the Colombian population, considering that it has not been previously reported.

The other VUS found in BRCA2 gene was the alteration c.125A>G (p.Tyr42Cys), classified as non pathogenic by the majority of the in silico tools (Table 4). This variant has been widely classified as a neutral variant 33 . Wu et al. 34 , and Kuznetsov et al. 35 , using different functional assays, compared the mutant and the wildtype forms of BRCA2 and concluded that p.Tyr42Cys variant has no effect on the BRCA2 function. These results are consistent with the results obtained in our in silico analysis, so we suggest that the BRCA2 p.Tyr42Cys variant is probably neutral.

For the intronic variant BRCA1 c.8112C>G, the integrated in silico tools in Alamut predicted that the natural splice site in exon 3 (c.81N) would be altered as shown in [Table 5], where four of five splicing tools show a percentage of variation higher than 10%. To have a better understanding of the effect of this mutation on exon 3 in the acceptor site, we used the NNsplice program, and after mutation, the program predicts that the normal acceptor site would be altered, and one new possible alternative site would be used, the program gives to this site a score of 0.97 and it corresponds to the acceptor site in exon 4 (tag//ATTTTGC), this would lead to loss of exon 3, and the generation of a premature stop codon. We therefore, suggest that the mutation BRCA1 c.81-12C>G is probably deleterious because the generation of significant changes in the BRCA1 protein; this mutation was found in three sisters, which belong to a family with a high incidence of BC (7 cases) and OC (4 cases).

Other missense mutation identified in BRCA1 was c.3119G>A (p.Ser1040Asn), the PolyPhen-2 algorithm predicts this change as probably damaging (0,974), just as PANTHER (3.46) and SNP&GO (7. 85%) (Table 4). The region in which this variant is located has been suggested to be a region of direct interaction of BRCA1 with the RAD51 protein; this direct binding with RAD51 has been proposed to occur at amino acids 758-1064 of BRCA1 36 , however, till date, there is still no consensus on whether this interaction is direct or indirect 37 , furthermore, the controversy regarding this variant role need to be clarified because some authors classify it as neutral 38 - 43 . Taking into account the interaction with RAD51, and the fact that three of the programs portray this position as highly conserved, we suggest that this variant is probably deleterious.

For the BRCA1 missense mutations c.3083G>A (p.Arg1028His), the majority of the in silico tools used, predict that this variant is neutral or tolerated (Table 4), but only the SNP&GO algorithm predicts this variant as disease inducing, however, the RI index lacks sufficient confidence for the prediction. These results are consistent with previous studies, among them is an analysis of the interspecific sequence variation in which the p.Arg1028His variant is classified as probably neutral or of little clinical significance 44 . Considering all the previous evidence, we can conclude that this variant is probably neutral.

Although, BRCA2 c.1114A>C (p.Asn372His) is considered as a polymorphism, this variant is located within the region that interacts with the histone acetyltransferase domain of the P300/CBP associated Factor (PCAF) protein 45 and has been associated with a 2.29fold (95% CI: 1.164.49; p= 0.016) increased risk, in families with no BRCA1/2 mutations with high-risk of BC 32 . Wen-Qiong et al. 46 , performed a pooled analysis, where the BRCA2 p.Asn372His variant was significantly associated with an increased risk of overall cancer (dominant model: OR= 1.07, 95% CI: 1.01-1.13; recessive model: OR= 1.12, 95% CI: 1.02-1.23). Therefore, we suggest that this variant could be considered as a low penetrance allele to breast cancer.

Additionally, the BRCA2 c.426-89T>C polymorphism was found in two families, in both cases, it was accompanied by the mutation c.865A>G (p.Asn289Asp) and the polymorphisms c.8755-66T>C and c.8851G>A. The BIC database reported this variant 37 times, and it is a normal allelic variant that does not play a direct role in the generation of tumors in breast cancer 47 .

We found that 11 (18.9%) of the families studied present germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2, and 9 of them were probably deleterious in the Pacific colombian region. Therefore, these mutations explain 15.5% of the breast/ovarian cancer cases in our sample. Additionally, all the individuals analyzed have, at least, one polymorphism, and none of the controls presented the classified mutations as probably deleterious in this study.

Mutation screening was performed using a combination of SSCP (single-strand conformational polymorphism) and sequencing analysis. Considering that the SSCP method has a sensitivity of 94% 48 it is possible that around 6% of mutations in the coding region of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes may have not been detected. Additionally, this work did not include the search for large genomic deletions and rearrangements which explain approximately 10% of all BRCA1 mutations 12 .

The spectrum of mutations found in this study is different from that reported in previous studies, which evaluated patients from the central region of Colombia 12 , 22 , 49 , 50 . We suggest that the main reason for this difference between studies, is that the Colombian population is the result of a complex process of admixture between European, African and Native Americans, in varying degrees, depending on the region 28 . Therefore, the extrapolation of results from one region to the rest of the Colombian population is risky, for example, the population of Southwestern Colombia, has a specific population dynamic and it is different from the central region 51 . These findings indicate that the Colombian population has a heterogeneous spectrum of BRCA mutations, so it is of utmost importance to generate studies where the different regions of the country are represented, in order to make a real approach to the Colombian mutational spectrum.

Conclusions

We found that 11 of the families studied present germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2, and 9 of them were probably deleterious. These mutations explain 15.5% of the breast/ovarian cancer cases in our sample

The most recurrent mutation in this study was BRCA2 c.865A>G we suggest the p.Asn289Asp mutation as being probably deleterious. Also, in the BRCA2 gene we report a novel mutation, the c.6427T>C (p.Ser2143Pro), we propose this, as a variant to be considered as an exclusive variant from the Colombian population.

For the intronic variant BRCA1 c.8112C>G we suggest that the mutation BRCA1 c.8112C>G is probably deleterious; this mutation was found in a family with a high incidence of BC and OC. Also, in the BRCA1 gene we report the mutation c.3119G>A (p.Ser1040Asn),we suggest that this variant is probably deleterious.

We considered then, that at this time, the use of genetics test based on mutational panels for BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Colombian patients, would not be informative enough, because of the diverse mutational spectrum of this population, which is evidenced in this work. Therefore, the mutational screening of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 entire coding regions, is necessary for the molecular genetic testing of the Colombian high-risk breast cancer patients.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the families who participated in the research studies described in this article. We also acknowledge the institutions involved in the study, Hospital Universitario del Valle, Fundación Fondo de Droga Contra el Cáncer (FUNCANCER), Clínica Universitaria Rafael Uribe Uribe from Cali and Hospital Universitario “San José” from Popayán.

Footnotes

Funding: COLCIENCIAS (Código 110651929134) and Vice-rectoria de Investigaciones - Universidad del Valle (CI7830).

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C. Rebelo M et al Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bravo LE, Collazos T, Collazos P, García LS, Correa P. Trends of cancer incidence and mortality in Cali, Colombia 50 years experience. Colomb Med (Col) 2012;43(4):246–255. doi: 10.25100/cm.v43i4.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266(5182):66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, Swift S, Seal S, Mangion J. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995;378(6559):789–792. doi: 10.1038/378789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes DR, Antoniou AC. Unravelling modifiers of breast and ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers update on genetic modifiers. J Intern Med. 2012;271:331–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thacker J. The RAD51 gene family, genetic instability and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2005;219(2):125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy-Lahad E, Lahad A, Eisenberg SA. A Single nucleotide polymorphism in the RAD51 gene modifies cancer risk in BRCA2 but not BRCA1 carriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(6):3232–3236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051624098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Didraga MA, van Beers EH, Joosse SA, Brandwijk KI, Oldenburg RA, Wessels LF. A non-BRCA1/2 hereditary breast cancer sub-group defined by aCGH profiling of genetically related patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130(2):425–436. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1357-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balmaña J, Díez O, Rubio IT, Cardoso F. BRCA in breast cancer ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(Suppl 6):vi31–vi34. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashton-prolla P, Vargas FR. Prevalence and impact of founder mutations in hereditary breast cancer in Latin America. Genet Mol Biol. 2014;37(1 Suppl):234–240. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572014000200009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rojas W, Parra MV, Campo O, Caro MA, Lopera JG, Arias W. Genetic make up and structure of Colombian populations by means of uniparental and biparental DNA markers. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;143(1):13–20. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres D, Rashid MU, Gil F, Umana A, Ramelli G, Robledo JF. High proportion of BRCA1/2 founder mutations in Hispanic breast/ovarian cancer families from Colombia. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103(2):225–232. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanabria MC, Muñoz G, Vargas CI. Análisis de las mutaciones más frecuentes del gen BRCA1 (185delAG y 5382insC) en mujeres con cáncer de mama en Bucaramanga, Colombia. Biomédica. 2009;29:61–72. doi: 10.7705/biomedica.v29i1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torres D, Umaña A, Robledo JF, Caicedo JJ, Quintero E, Orozco A. Estudio de factores genéticos para cáncer de mama en Colombia. Universitas Medica. 2009;50(3):297–301. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodríguez AO, Llacuachaqui M, Pardo GG, Royer R, Larson G, Weitzel JN. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among ovarian cancer patients from Colombia. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Londoño-Hernández JE, Llacuachaqui M, Palacio GV, Figueroa JD, Madrid J, Lema M. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in unselected breast cancer patients from medellín, Colombia. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2014;12:11–15. doi: 10.1186/1897-4287-12-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16(3):1215–1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barker DF. Direct genomic multiplex PCR for BRCA1 and application to mutation detection by single-strand conformation and heteroduplex analysis. Hum Mutat. 2000;16(4):334–344. doi: 10.1002/1098-1004(200010)16:4<334::AID-HUMU6>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orita M, Iwahana H, Kanazawat H, Hayashi K, Sekiya T. Detection of polymorphisms of human DNA by gel electrophoresis as single-strand conformation polymorphisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2766–2770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naranjo J, Posso A, Cárdenas H, Muñoz JE. Detección de variantes alélicas de la kappa-caseína en bovinos Hartón del Valle. Rev Acta Agronóm. 2007;56(1):43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Théry JC, Krieger S, Gaildrat P, Révillion F, Buisine M-P, Killian A. Contribution of bioinformatics predictions and functional splicing assays to the interpretation of unclassified variants of the BRCA genes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(10):1052–1058. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arias-Blanco JF, Ospino-Durán EA, Restrepo-Fernández CM, Guzmán-AbiSaab L, Fonseca-Mendoza DJ, Ángel-Guevara DI. Frecuencia de mutación y de variantes de secuencia para los genes BRCA1 y BRCA2 en una muestra de mujeres colombianas con sospecha de síndrome de cáncer de mama hereditario serie de casos. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 2015;66(4):287–296. doi: 10.18597/rcog.294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Oliveira ES, Soares BL, Lemos S, Rosa RCA, Rodrigues AN, Barbosa LA, dos Santos LL. Screening of the BRCA1 gene in Brazilian patients with breast and/or ovarian cancer via high-resolution melting reaction analysis. Fam Cancer. 2016;15(2):173–181. doi: 10.1007/s10689-015-9858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solano A, Aceto G, Delettieres D, Veschi S, Neuman M, Alonso E. BRCA1 and BRCA2 analysis of Argentinean breast/ovarian cancer patients selected for age and family history highlights a role for novel mutations of putative south-American origin. Springerplus. 2012;1:20–20. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lara K, Consigliere N, Pérez J, Porco A. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer patients from Venezuela. Biol Res. 2012;45:117–130. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602012000200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruiz-Flores P, Sinilnikova OM, Badzioch M, Calderon-Garcidueñas a L, Chopin S, Fabrice O. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation analysis of early-onset and familial breast cancer cases in Mexico. Hum Mutat. 2002;20(6):474–475. doi: 10.1002/humu.9084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dufloth RM, Carvalho S, Heinrich JK, Shinzato JY, dos Santos CC, Zeferino LC. Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Brazilian breast cancer patients with positive family history. Sao Paulo Med J. 2005;123(4):192–197. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802005000400007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salas A, Acosta A, Alvarez-Iglesias V, Cerezo M, Phillips C, Lareu M V. The mtDNA ancestry of admixed Colombian populations. Am J Hum Biol. 2008;20(5):584–591. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tommasi S, Pilato B, Pinto R, Monaco A, Bruno M, Campana M. Molecular and in silico analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants. Mutat Res Mol Mech. 2008;644(1-2):64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mondal G, Rowley M, Guidugli L, Wu J, Pankratz VS, Couch FJ. BRCA2 localization to the midbody by filamin a regulates CEP55 signaling and completion of cytokinesis. Dev Cell. 2012;23:137–152. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agromayor M, Martin-Serrano J. Knowing when to cut and run mechanisms that control cytokinetic abscission. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23(9):433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seymour I J, Casadei S, Zampiga V, Rosato S, Danesi R, Falcini F. Disease family history and modification of breast cancer risk in common BRCA2 variants. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:783–786. doi: 10.3892/or.19.3.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldgar D E, Easton D F, Deffenbaugh A M, Monteiro ANA, Tavtigian S V, Couch FJ. Integrated evaluation of DNA sequence variants of unknown clinical significance. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:535–544. doi: 10.1086/424388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu K, Hinson S R, Ohashi A, Farrugia D, Wendt P, Tavtigian S V. functional evaluation and cancer risk assessment of BRCA2 unclassified variants. Cancer Res. 2005;65(2):417–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuznetsov S G, Liu P, Sharan S K. Mouse embryonic stem cell-based functional assay to evaluate mutations in BRCA2. Nat Med. 2008;14(8):875–881. doi: 10.1038/nm.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scully R, Chen J, Plug A, Xiao Y, Weaver D, Feunteun J. Association of BRCA1 with Rad51 in mitotic and meiotic cells. Cell. 1997;88:265–275. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81847-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caestecker KW. Van de Walle GR The role of BRCA1 in DNA double-strand repair Past and present. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319(5):575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durocher F, Shattuck-eidens D, Mcclure M, Labrie F, Skolnick MH, Goldgar DE. Comparison of BRCA1 polymorphisms, rare sequence variants and/or missense mutations in unaffected and breast/ovarian cancer populations. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5(6):835–842. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnold N, Peper H, Bandick K, Kreikemeier M, Karow D, Teegen B. Establishing a control population to screen for the occurrence of nineteen unclassified variants in the BRCA1 gene by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B. 2002;782(1-2):99–104. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De La Hoya M, Diaz-Rubio E, Calde T. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis-based analysis of loss of heterozygosity distinguishes nonobvious, deleterious BRCA1 variants from nonpathogenic polymorphisms. Clin Chem. 1999;45(11):2028–2030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Infante M, Duran M, Esteban-Cardeñosa E, Miner C, Velasco E. High proportion of novel mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast/ovarian cancer patients from Castilla-León (central Spain) J Hum Genet. 2006;51:611–617. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0404-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Claes K, Poppe B, Coene I, Paepe AD, Messiaen L. BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutation spectrum and frequencies in Belgian breast/ovarian cancer families. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(6):1244–1251. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tavtigian S V, Deffenbaugh A M, Yin L, Judkins T, Scholl T, Samollow PB. Comprehensive statistical study of 452 BRCA1 missense substitutions with classification of eight recurrent substitutions as neutral. J Med Genet. 2006;43(4):295–305. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.033878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abkevich V, Zharkikh A, Deffenbaugh A M, Frank D, Chen Y, Shattuck D. Analysis of missense variation in human BRCA1 in the context of interspecific sequence variation. J Med Genet. 2004;41(7):492–507. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.015867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teare MD, Cox A, Shorto J, Anderson C, Bishop DT, Cannings C. Heterozygote excess is repeatedly observed in females at the BRCA2 locus N372H. J Med Genet. 2004;41(7):523–528. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.017293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wen-Qiong X, Yong-Qiao H, Jin-Hong Z, Jian-Qun M, Jing H, Wei-Hua J. Association of BRCA2 N372H polymorphism with cancer susceptibility a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6791–6791. doi: 10.1038/srep06791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawahara M, Sakayori M, Shiraishi K, Nomizu T, Takeda M, Abe R. Identification and evaluation of 55 genetic variations in the BRCA1 and the BRCA2 genes of patients from 50 Japanese breast cancer families. J Hum Genet. 2004;49:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gross E, Arnold N, Goette J, Schwarz-Boeger U, Kiechle M. A comparison of BRCA1 mutation analysis by direct sequencing, SSCP and DHPLC. Hum Genet. 1999;105:72–78. doi: 10.1007/s004399900092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Briceño-Balcazar I, Gómez-Gutiérrez A, Díaz-Dussán NA, Noguera-Santamaría MC, Díaz-Rincón D, Casas-Gómez MC. Mutational spectrum in breast cancer associated BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in Colombia. Colomb Med (Col) 2017;48(2):58–63. doi: 10.25100/cm.v48i2.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cock-Rada AM, Ossa CA, Garcia HI, Gomez LR. A multi-gene panel study in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in Colombia. Fam Cancer. 2018;17(1):23–30. doi: 10.1007/s10689-017-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Avila S, Briceño I, Gomez A. Genetic population analysis of 17 Y-chromosomal STRs in three states (Valle del Cauca, Cauca and Nariño) from Southwestern Colombia. J Forensic Leg Med. 2009;16(4):204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]