Abstract

Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), a serine/threonine phosphatase, has been shown to control T cell function. We found that in vitro–activated B cells and B cells from various lupus-prone mice and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus display increased PP2A activity. To understand the contribution of PP2A to B cell function, we generated a Cd19CrePpp2r1afl/fl (flox/flox) mouse which lacks functional PP2A only in B cells. Flox/flox mice displayed reduced spontaneous germinal center formation and decreased responses to T cell-dependent and T-independent antigens, while their B cells responded poorly in vitro to stimulation with an anti-CD40 antibody or CpG in the presence of IL-4. Transcriptome and metabolome studies revealed altered nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and purine/pyrimidine metabolism and increased expression of purine nucleoside phosphorylase in PP2A-deficient B cells. Our results demonstrate that PP2A is required for optimal B cell function and may contribute to increased B cell activity in systemic autoimmunity.

Keywords: Autoimmunity, Immunology

Keywords: B cells

Introduction

B cells encounter antigens in secondary lymphoid organs and respond by proliferating and undergoing maturation and differentiation, which include class-switch recombination (CSR), Ab affinity maturation, and generation of memory B cells and plasma cells (1, 2). T-independent responses are elicited by polysaccharides that engage the B cell receptor (BCR) or CpG motifs and result in polyclonal B cell activation (3–5). T-dependent responses are elicited by proteins, such as 4-Hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl-chicken γ-globulin (NP-CGG), that are processed and presented to cognate Th cells for recognition by B cells (6). CD40 engagement by its ligand, which is expressed on T cells, is essential for T cell–dependent Ab responses and represents a major contributor to Ig production (7, 8). In vivo, activated mature B cells proliferate and form the germinal centers (GCs) where high-affinity, long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells are generated (1, 9, 10). GCs develop spontaneously without exposure to foreign antigens (11–15) in murine lupus and human systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and this dysregulation results in the production of autoantibodies (12, 13, 16–20).

Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is a serine/threonine phosphatase ubiquitously expressed in eukaryotic cells and comprises a scaffold-type structural subunit (A), a catalytic subunit (C), and a regulatory subunit (B) (21). There are 2 isoforms for the structural subunit (Aα and Aβ), 2 isoforms for the catalytic subunit (Cα and Cβ), and more than 20 regulatory subunits that enable PP2A to act on a wide range of substrates and to participate in cellular processes like cell cycle, gene transcription, and apoptosis (22, 23). PP2A levels and activity are increased in T cells from patients with SLE and account for decreased IL-2 production (24–27). Transgenic mice that overexpress the catalytic subunit PP2AC in T cells develop susceptibility to glomerulonephritis (28), whereas PP2A is requisite for Treg function (29). In addition, studies in patients with acute (30) and chronic B lymphocytic leukemia have signified the importance of PP2A in B cell oncogenesis (31). Given the central role of PP2A in the regulation of many key cellular processes and its role in human disease pathogenesis, therapeutic modalities targeting PP2A are being developed (32). The involvement of serine/threonine phosphatases in the B cell–dependent expression of autoimmunity is not known.

Here, we present evidence that PP2A activity is increased in in vitro–activated B cells and in B cells from lupus-prone mice. We also show that PP2A expression is increased in B cells from patients with SLE. The newly constructed mouse, which lacks PP2A in B cells, responds poorly to immunization with T-dependent and T-independent antigens, with decreased GC formation and plasmablast/plasma cell differentiation. When stimulated in vitro, B cells from Cd19CrePpp2r1afl/fl (flox/flox) mice show decreased Ig production with decreased CSR and plasmablast/plasma cell differentiation. This globally defective B cell response can be explained by differences in NAD and purine/pyrimidine metabolism and purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) expression. We propose that B cell function depends on PP2A, and its downregulation in B cells from patients with SLE should have therapeutic value.

Results

Increased PP2A expression and function in activated B cells or B cells from lupus-prone mice and SLE patients.

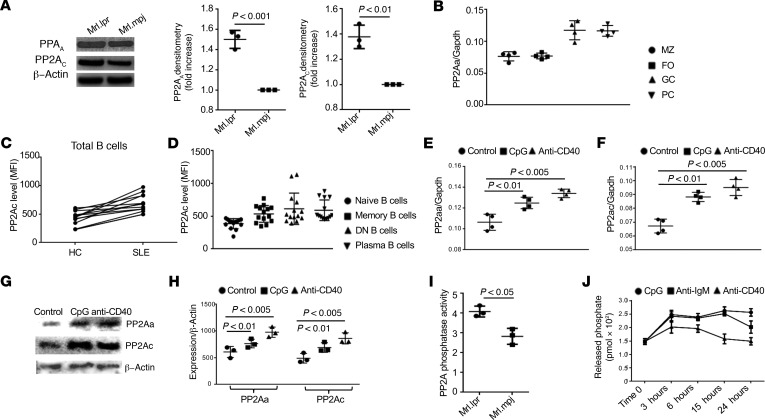

SLE is characterized by multiple B cell abnormalities leading to autoantibody production. Mrl.lpr, B6.lpr, and the triple-congenic NZM2410-derived SLE1.2.3 (SLE1.2.3) mice develop lupus spontaneously and display many features of human SLE, including autoantibody production and renal immune complex deposition. To examine whether PP2A has a role in B cell function in systemic autoimmunity, we measured PP2A protein levels in B cells from these mice. PP2AA and PP2AC protein levels were both increased in B cells from lupus-prone mice compared with matched controls (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.130655DS1). We next asked whether PP2A expression was restricted in certain subsets of B cells during development and differentiation. Marginal zone B cells (MZ), follicular B cells (FO), GC B cells, and plasma B cells (PC) were sorted out from MRL/lpr mice and subjected to quantitative PCR (qPCR) (33). All subsets were found to express PP2AA, but its expression was higher in GC B cells and PC (Figure 1B). To extend our studies to humans, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with SLE and matched healthy controls were isolated and stained for PP2Ac (the catalytic subunit) (34). Consistently, PP2AC levels were found increased, as determined by flow cytometry, in B cells from SLE patients; even the expression doesn’t correlate well with SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI; Figure 1C and Supplemental Figure 2). Of note, B cells with activating or activated phenotypes including memory B cells (CD19+IgD–CD27+), double negative (DN, CD19+IgD–CD27–) B cells, and PC (CD19+CD138+IgG+) displayed higher expression of PP2AC compared with naive B cells (CD19+IgD+CD27–) (Figure 1D). We postulated that certain stimuli that activate B cells might drive the expression of PP2A. To test our hypothesis, purified B cells were stimulated with either CpG or anti-CD40, and the expression of PP2AA and PP2AC (Figure 1, E and F) was quantified by qPCR. As expected, stimulation increased the expression of both PP2A subunits. Western blot analysis validated the increased expression of PP2AA and PP2AC (Figure 1, G and H) at the protein level. Increased protein levels of PP2As were accompanied with increased enzymatic activity in B cells from lupus-prone mice compared with matched controls (Figure 1I and Supplemental Figure 3), and in CpG or anti-CD40 stimulated B cells compared with unstimulated control (Figure 1J). Our results imply that enhanced PP2A phosphatase activity in B cells may contribute to the pathogenesis of lupus.

Figure 1. Increased PP2A expression and enhanced function in activated B cells or B cells from lupus-prone mice and SLE patients.

(A) Western blot analysis on the expression of both scaffold (PP2AA) and catalytic (PP2AC) subunits in splenic B cells isolated from the indicated mice. Quantification of Western blots (n = 3 per experiment, a representative experiment and pooled densitometry of the 3 experiments are shown). (B) Germinal center B cells (GC, CD19+FAS+GL7+), plasma cells (PC, CD19+IgG+CD138hi), marginal zone B cells (MZ, CD19+CD21+CD23lo), and follicular B cells (FO, CD19+CD21loCD23hi) were FACS sorted for qPCR. Dot plots show the expression of PP2AA, and elevated expression was observed in GC and PC compared with MZ and FO. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of the expression of PP2Ac (indicated by mean florescence intensity, MFI) in total B cells from patients with SLE and matched healthy controls. (D) Dot plots show the increased MFI of PP2Ac in DN B cells (CD19+IgD–CD27–), memory B cells (CD19+IgD–CD27+), and plasma B cells (CD19+IgG+CD138+) compared with naive B cells (CD19+IgD+CD27–). (E–H) CD19+ human B cells were enriched by magnetic beads and cultured with the indicated stimuli for the indicated time. (E) Dot plots show the expression of PP2Aa in B cells stimulated with either CpG or anti-CD40 compared with unstimulated B cells 3 hours after stimulation. (F) Dot plots show the expression of PP2Aa in B cells stimulated with either CpG or anti-CD40 compared with unstimulated B cells 3 hours after stimulation. (G) Western blot analysis of the expression of PP2Aa and PP2Ac in human B cells stimulated with either CpG or anti-CD40 for 48 hours. (H) Dot plots show the quantification of PP2Aa and expression PP2Ac in human B cells stimulated with either CpG or anti-CD40 compared with control unstimulated B cells 3 hours after stimulation. (I and J) PP2A phosphatase activity was quantified using a kit from R&D. The activity of PP2A is presented as the rate of phosphate release (pmol × 102). (I) Bar graph shows the PP2A phosphatase activity in ex vivo splenic B cells from lupus-prone Mrl.lpr mice compared with matching control Mrl.mpj mice (data pooled from 3 independent experiments, paired t test, mean ± SEM). (J) Splenic B cells were enriched from C57BL/6J WT mice by MACS and stimulated with the indicated reagents for several time periods; kinetic curves show the PP2A phosphatase activity (n = 3 for 3 independent experiments, 2-way ANOVA analysis, mean ± SEM).

PP2A is required for B cell activation and Ig production in vitro.

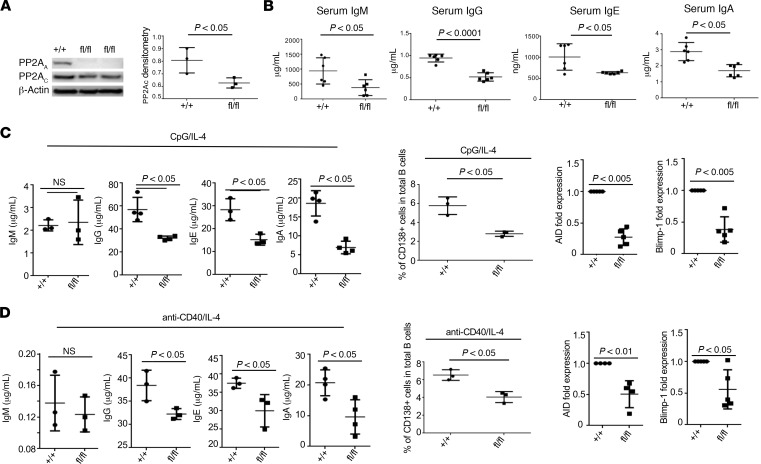

To study the role of PP2A in B cell function, we constructed a flox/flox mouse that lacks the dominant α isoform of the scaffold PP2AA subunit in B cells and studied it along with Cd19CrePpp2r1a+/+ (control) mice. Flox/flox mice did not express the scaffold PP2AA subunit and display decreased protein levels of the catalytic PP2Ac subunit (Figure 2A). However, the B cells in the spleen (Supplemental Figure 4A) and BM (data not shown) of flox/flox mice were intact and displayed comparable ex vivo apoptosis rates (Supplemental Figure 4B). Because PP2A has been reported to affect B cell survival in a variety of B cell malignancies (31), the development of different subsets of B cells was carefully examined. We did not detect any significant differences in the percentage or the absolute numbers of transitional B cells, MZ, and FO between flox/flox and control mice (data not shown). PP2AA was efficiently deleted but the deletion was restricted in B cells, and expectedly, we did not find any differences in the percentages of total T cells, CD4+ T cells, or CD8+ T cells (data not shown). Interestingly, total serum IgM, IgG, IgG1, and IgA levels were significantly decreased in flox/flox compared with control mice (Figure 2B), which suggested that PP2A may play a role in B cell activation and Ab production. To assess this possibility, B cells from either control or flox/flox mice were cultured in vitro in the presence of CpG and IL-4 (Figure 2C). As expected, stimulation with CpG efficiently switched most mature IgM+ mature B cells into IgG-producing cells, as indicated by higher titers of IgG but low titers of IgM released into culture medium. Of note, B cells with PP2AA deficiency displayed significantly reduced ability to differentiate into plasma cells and produce antibodies. Induction of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) and Blimp-1 during B cell activation is essential for B cell differentiation and isotype switching. Not surprisingly, failure of induction of AID and Blimp-1 was observed in B cells with PP2AA deficiency (Figure 2C). Next, we stimulated B cells with anti-CD40 in the presence of IL-4. Consistently, reduced plasma cell formation and failure of AID/Blimp-1 induction were also observed in B cells from flox/flox mice compared with control mice (Figure 2D). Equal proliferation and surviving rate of B cells from flox/flox mice or control mice in the presence of stimulation excluded the possibility that PP2AA indirectly affects Ig production through regulation on survival and proliferation (Supplemental Figure 4, C and D). Collectively, our data indicate that, in B cells, PP2A is required for cell activation and differentiation.

Figure 2. PP2A is important for B cell activation and Ig production in vitro.

(A) Western blot analysis of PP2Aa and PP2Ac subunit expression in isolated B cells from the indicated mice. Quantification of PP2Ac expression in isolated B cells from the indicated mice. (B) ELISA analysis of the indicated serum Ig levels from the indicated mice (12–24 weeks old) (n = 3 mice per group for 2 independent experiments). (C and D) Splenic B cells were isolated from the indicated mice and were stimulated with either CpG or anti-CD40 in the presence of IL-4 for 72 hours. (C) Left: ELISA analysis of the indicated Ig produced by in vitro cultured B cells with CpG and IL-4 stimulation. Middle: Dot plots represent the percentages of IgG+CD138+ plasma cells in total cultured B cells in the presence of CpG plus IL-4. Right: qPCR analysis on the expression of the indicated gene expression by the indicated B cells (n = 3 per group for 2 independent experiments). (D) Left: ELISA analysis of the indicated Ig produced by in vitro cultured B cells after anti-CD40 and IL-4 stimulation. Middle: Dot plots indicate the percentages of IgG+CD138+ plasma cells in total B cells cultured with anti-CD40 and IL-4. Right: qPCR analysis of indicated genes in the indicated B cells (n = 3 per group for 2 independent experiments). Paired t test, mean ± SEM.

PP2A is critical for B cell activation and differentiation and Ig production in vivo.

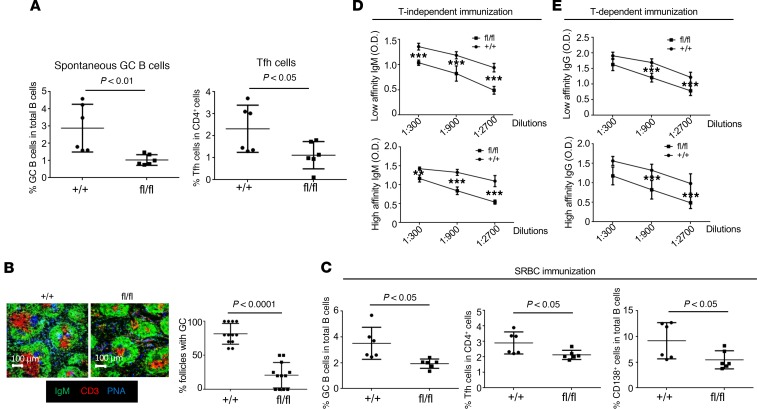

Interestingly, the percentages of both spontaneous GC B cells (CD19+FAS+PNA+) and T follicular helper cells (Tfh) (CD4+CXCR5hiPD1hi) in the spleens of flox/flox mice with middle ages were significantly reduced compared with age-matched controls (Figure 3A), which indicates that PP2AA contributes to B cell activation and differentiation in vivo. To validate our observation in vitro, control and flox/flox mice were immunized with sheep RBCs (SRBCs), which stimulate B cells polyclonally and induce GC formation. Confocal image analysis revealed that flox/flox mice immunized with SRBC developed significantly fewer GCs with smaller sizes in the spleens (Figure 3B). Flow cytometry analysis further confirmed the reduction of GC B cells, Tfh cells, and CD138+ plasmablast/plasma cells (Figure 3C) (35). Consistently, flox/flox mice immunized with either T-independent antigen NP-Ficoll (Figure 3D) or T-dependent antigen NP-CGG (Figure 3E) developed much lower NP-specific antibodies. Taken together, our results demonstrated that PP2A played a critical role duirng B cell activation and differentiation.

Figure 3. PP2A is critical for B cell activation, differentiation, and Ig production in vivo.

(A) Dot plots show the percentages of spontaneous germinal center B cells (GC-CD19+FAS+PNA+) and T follicular helper cells (Tfh-CD4+CXCR5hiPD1hi) in spleens of the indicated 24-week-old mice (n = 6 mice per group for 2 independent experiments). (B and C) Mice were immunized i.p. with 0.2 mL/mouse SRBC. (B) IHC staining of frozen spleen sections of the indicated mice (n = 3 mice per group in 2 independent experiments). Bar graphs show the quantification (percentage) of follicles with germinal centers in total splenic follicles from the indicated mice (n = 3 mice per group in 2 independent experiments). (C) Flow cytometry analysis (%) of germinal center B cells (GC-CD19+FAS+PNA+), T follicular helper cells (Tfh-CD4+CXCR5hiPD1hi), and IgG plasma cells (PC-CD19+IgG+CD138+) in the spleens of the indicated mice after SRBC immunization. (D and E) Indicated mice were i.p. immunized with 100 μg/mouse NP-Ficoll for 5 days or 100 μg/mouse NP-CGG in 5% alum for 14 days. (D) ELISA analysis for high affinity (NP-7) or low affinity (NP-41) for NP antigen-specific IgM in the serum of 12-week-old flox/flox mice compared with control mice 5 days after immunization with T-independent antigen NP-Ficoll (n = 3 per group in 2 independent experiments). (E) ELISA analysis of high affinity (NP-7) or all affinity (NP-41) NP antigen-specific IgG in the serum of 12-week-old flox/flox mice compared with control mice 14 days after immunization with T-dependent antigen NP-CGG (n = 3 per group in 2 independent experiments). Paired t test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.05, mean ± SEM.

PP2A expression in B cells contributes to disease pathogenesis in pristine-induced lupus.

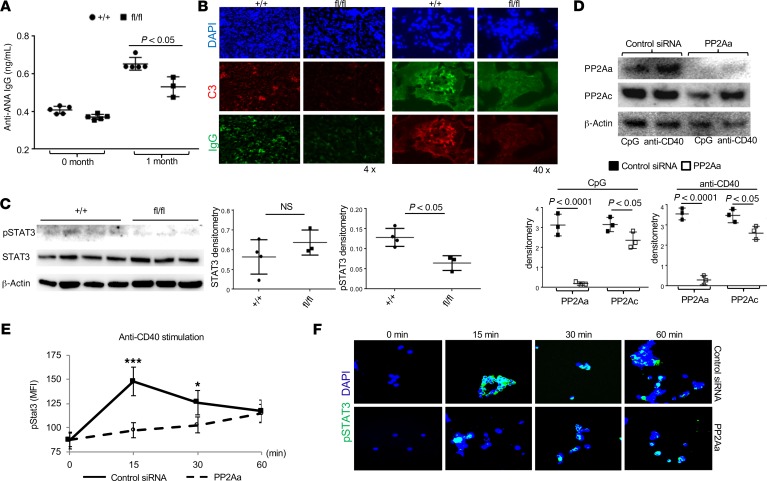

Next, we asked whether mice that lack PP2A in B cells can develop lupus-like manifestations when injected with pristine, a substance known to induce lupus-like sydrome in normal mice. Control and flox/flox mice were administrated pristine i.p., and we recorded that the flox/flox mice displayed reduced titers of anti–ANA IgG in the circulation (Figure 4A), with decreased IgG deposition in the kidneys (Figure 4B). These data imply that the presence of PP2A in B cells is needed for the development of autoimmunity.

Figure 4. PP2A expression in B cells for disease development in mice after injection of pristine.

(A and B) Indicated mice were challenged i.p. with 0.5 mL pristine. (A) Blot graph shows ANA antibody levels in the serum of flox/flox and control mice 1 month after pristine challenge (n = 6 mice per group). (B) Immunofluorescence image analysis to detect IgG deposition in the kidneys of flox/flox and control mice 6 months after pristine challenge (n = 6 mice per group). (C) Western blot analysis on pSTAT3 and total STAT3 expression in B cells with PP2A deficiency. Quantification of Western blots. (D–F) Human B cells were enriched from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) using MACS cell separation kits. (D) Western blot analysis to detect PP2Aa and PP2Ac in human B cells treated with control or PP2Aa siRNA. Quantification of Western blot densities. (E) Flow cytometry analysis on pSTAT3 induction during B cell activation in the absence of PP2Aa. (F) Immunofluorescence image analysis on pSTAT3 expression during B cell activation in the absence of PP2Aa. Original magnification ×63. Paired t test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005, mean ± SEM.

To identify PP2A downstream molecules, we sorted B cells and subjected their lysates for Western blot analysis. STAT3 is constitutively expressed in B cells and increases after activation. Since dysregulated STAT3 pathway in B cells is linked to lupus pathogenesis (36, 37), we examined the expression of STAT3 and pSTAT3 in total B cells from either flox/flox or control mice. To our surprise, pSTAT3 level in B cells from flox/flox mice was signifcantly reduced compared with the controls, even though the levels of total STAT3 were comparable between the 2 mice (Figure 4C). Furthermore, we extended this observation in human primary B cells in which we successfully silenced PP2AA using a Ppp2r1a siRNA (Figure 4D). After stimulation with anti-CD40, both flow cytometry (Figure 4E) and confocal image analysis (Figure 4F) revealed that, in the absence of PP2AA, there was a delayed and reduced pSTAT3 response in B cells. Collectively, our results strongly suggest that PP2A functions upstream of STAT3 during B cell activation.

PP2A in B cells inhibits mitochondrial respiration by suppressing expression of PNP, which is involved in purine and pyrimidine metabolism.

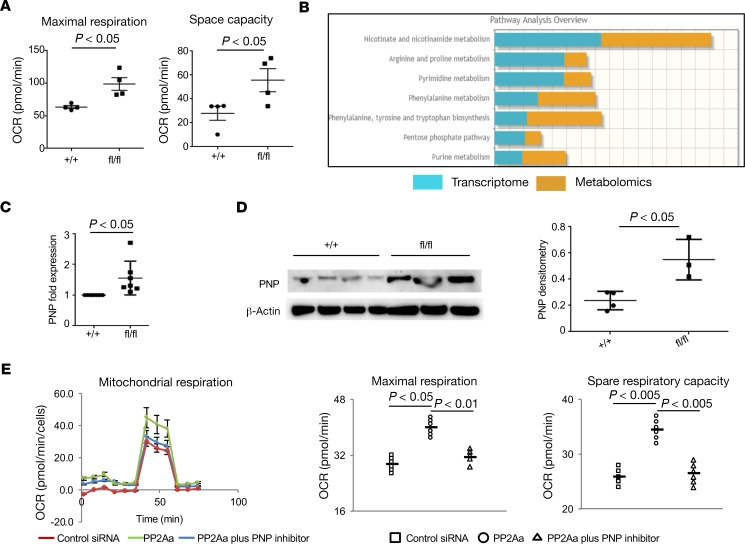

Considering that metabolic reprogramming is essential for B cell activation and Ab production (38), we decided to measure different metabolic parameters in B cells with Ppp2r1a deficiency. Seahorse metabolic analysis revealed that flox/flox B cells have increased mitochondrial respiration (maximal oxygen consumption rate [OCR] and space capacity OCR) but normal glycolysis rates (Figure 5A and data not shown). It has been shown that mitochondria provide instructive signals for several processes of B cells, including CSR and PC differentiation (39). Therefore, PP2A might regulate B cell differentiation and isotype switching through modulation of mitochondrial function. To further trace the pathways that are affected in the absence of PP2A in B cells, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (Supplemental Table 1) and metabolomics analysis (Supplemental Figure 5) in B cells from flox/flox mice and from control mice. Data obtained from the RNA-seq and metabolomics studies were combined to generate integrated metabolic pathway analysis, which revealed significant alterations in NAD, purine metabolism, and pyrimidine metabolism (Figure 5B and Supplemental Figure 6). Joint analysis showed a significant increase in PNP expression in B cells from flox/flox mice, which was further confirmed by mRNA expression (qPCR) (Figure 5C) and protein expression (Western blotting) (Figure 5D). Consistently, human B cells treated with Ppp2r1a siRNA displayed increased mitochondrial respiration (maximal OCR and space capacity OCR), and interestingly, addition of 9-Deazaguanine (a potent inhibitor of PNP) efficiently suppressed the enhanced mitochondrial respiration mediated by PP2A deficiency back to normal level, which validate the suppression of PNP mediated by PP2A during B cell activation (Figure 5E).

Figure 5. PP2A in B cells inhibits mitochondrial respiration by suppressing the expression of purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP).

(A) Dot plots show mitochondrial respiration in Ppp2r1a-deficient mouse splenic B cells compared with WT mouse splenic B cells (maximal oxygen consumption rate [OCR]and space capacity OCR) (n = 4 independent experiments). (B) Joint analysis of RNA sequencing and metabolomics in B cells from flox/flox mice compared with control mice (n = 3 mice per group). (C) Increased PNP mRNA expression in B cells from flox/flox mice compared with control mice (n = 6 mice per group for qPCR experiment). (D) Western blot analysis on PNP expression in mouse splenic B cells with PP2Aa deficiency compared with WT controls. Quantification of Western blots. (E) Human primary B cells were enriched from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). Left: Representation of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of human primary B cells exposed to the indicated treatments (9-Deazaguanine was applied as PNP inhibitor). Right: Dot plots indicate mitochondrial respiration in human primary B cells with PP2Aa deficiency compared with controls exposed to the indicated treatments. Paired t test, mean ± SEM.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that PP2A is required for optimal B cell function and that PP2A is increased in B cells of humans and mice with SLE. In the absence of PP2A, GC form poorly, and plasma cell generation is decreased. Mice with B cells deficient in PP2A cannot raise proper responses to T-dependent and T-independent antigens. Consistently, mice with PP2A deficiency in B cells are resistant to lupus in a pristine induced murine model. At the molecular level, we showed that PP2A expression in B cells is essential for proper STAT3 phosphorylation and downstream signaling during activation. We further show that deficiency of PP2A in B cells promotes oxidative phosphorylation and increases the expression of PNP, the key metabolic enzyme that is essential for purine metabolism and mitochondrial function. It has been reported that changes in mitochondrial function are essential in providing instructive and stochastic signals to activated B cells for cell fate determination; thus, PP2A expression in B cells contributes heavily to plasma cell differentiation and Ig production (39).

In agreement with our findings is the report that B cell–specific regulatory subunit G5PR (Ppp2R3C) transgenic mice have augmented generation of GC, and after aging, they produce autoantibodies (30). We did not observe reduced B cell numbers in vivo with increased apoptosis, a discrepancy with observations reported in mice lacking the regulatory subunit G5PR in B cells (40), which can be explained by the fact that PP2A regulatory subunits dictate substrate and cell function specificity (41).

Our metabolomics and genomics studies pointed to defects in the NAD, purine metabolism, and pentose phosphate pathway, which is in agreement with studies in cells from patients with acute B cell lymphoblastic leukemia (30). Increased PP2A in B cells from patients with SLE and lupus-prone mice may facilitate the expansion of B cells and their differentiation into Ig-secreting cells. Mice lacking PP2A in B cells displayed a compromised ability to generate GC needed for the completion of the immune response. Interestingly, we found that PNP expression is increased when B cells lack PP2A. Functional polymorphisms of PNP have been linked to IFN type I–linked SLE immunopathology (42), and T cells from patients with SLE — which have increased expression of PP2A (24) — have been reported to have decreased levels of PNP, suggesting a protective role for this important metabolic enzyme in autoimmunity (43). In parallel, PNP deficiency causes severe combined immunodeficiency, with a third of the patients developing humoral autoimmunity (44).

Our studies document that PP2A is required to generate a sufficient immune response to antigens and suggest that drugs or adjuvants able to increase PP2A activity in B cells may improve the efficacy of vaccines. Conversely, curtailment of the activity of PP2A in B cells may offer a novel tool to suppress autoimmune disease activity (45).

Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6J (strain 000664) and Cd19Cre (strain 006785) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Ppp2r1afl/fl mice (strain: 017441, the Jackson Laboratory, FVB background) were backcrossed for at least 7 generations into C57BL/6J mice. Subsequently, they were bred with Cd19Cre to generate Cd19CrePpp2r1afl/fl mice. Mrl.lpr (strain 000485), Mrl.mpj (strain 000486), SLE1.2.3 (strain 007228), and B6.lpr (strain 000482) were also purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Both age- and sex-matched male and female mice at the age of 10–14 weeks were used for experiments. All mice were bred and housed in a specific pathogen–free environment in a barrier facility, in accordance to the BIDMC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunization and blood sampling.

Twelve-week-old mice of indicated genotype were immunized i.p. by 0.2 mL/mouse SRBC (100% packed, Innovative Research), 100 μg/mouse NP21-CGG (Biosearch Technologies) in 5% alum (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 100 μg/mouse NP21-Ficoll (Biosearch Technologies) as indicated in the experiments. Blood was collected through tail vein on day 5 after NP-Ficoll immunization or day 14 after NP-CGG immunization. Blood and splenocytes were collected during necropsy after SRBC and NP-CGG immunization. Anti-NP antibodies in the serum were measured by ELISA in which the target antigens (BioSearch Technologies) were either NP7–BSA (NP7-BSA) (a low hapten density with a molar ratio of NP to BSA of approximately 7) to detect high-affinity anti-NP antibodies; or NP41-BSA (a high hapten density with a molar ratio of NP to BSA of approximately 41) to detect both high- and low-affinity anti-NP antibodies.

Human samples.

Peripheral blood from patients with SLE and normal subjects used in this study were procured under BIDMC IRB number 2006P000298. B cells were isolated by negative selection using MACS cell separation kits (Miltenyi Biotec).

Mouse B cell isolation and culture.

B cells were isolated from spleens by negative selection using MACS cell separation kits (Miltenyi Biotec). RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog 11875085) with 10% FCS, 1% glutamate, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibo) were applied for cell culture. Two million B cells (1 million/mL) were cultured per well with CpG (InvivoGen, 3 μg/mL) plus recombinant murine IL-4 (R&D Systems, 50 ng/mL) or anti-CD40 (BioLegend, catalog 553721, 100 ng/mL) plus IL-4 (R&D Systems, 50 ng/mL) for 72 hours.

Flow cytometry.

Freshly isolated mouse splenocytes and BM cells from unimmunized and immunized mice were stained as indicated in the Results section for GC B cells (CD19+FAS+GL7+), transitional B cells (CD19+CD21+CD23hi), MZ (CD19+CD21+CD23lo), FO (CD19+CD21loCD23hi), plasma cells (CD19+IgG+CD138hi), CD4+ T cells (CD90.2+TCRαβ+CD4+), CD8+ T cells (CD90.2+TCRαβ+CD8+), and Tfh (CD90.2+TCRαβ+CD4+PD1+CXCR5+). PBMCs were isolated from blood samples of patients with SLE and age-, sex-, and race-matched healthy controls by Ficoll-gradient method. PBMCs were stained as indicated in the Results section.

The following antibodies were applied: anti-CD4 (RM4-5 or GK1.5, BioLegend), anti-CD19 (6D5, BioLegend), anti–GL-7 (GL7, eBioscience); B220 (RA3-6B2, BioLegend), PE–Cy7 anti-CXCR5 (2G8, BD Biosciences), and anti-ICOS (398.4A, 7E.17G9, eBioscience); and antibodies against PD-1 (RMP1-30, BioLegend), CD28 (37.51, eBioscience), CD40L (MR1, eBioscience), CD62L (MEL-14, BD Biosciences), CD44 (IM7, BioLegend), and Fas (15A7, eBioscience). Peanut agglutinin (PNA) was conjugated with biotin (Vector Laboratory) and was detected by Alexa350-conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen). PE-conjugated anti-PP2AC Ab (Clone 1D6) was purchased from MilliporeSigma.

In vitro B cell studies.

Proliferation was studied by CFSE dye dilution. The cells were loaded with CFSE on day 0, and flow cytometry was performed on B cells cultured for 4 days. Apoptosis was studied by annexin V plus propidium iodide staining on day 4 of culture by flow cytometry. CSR was studied in B cells through the detection of AID on day 4 of in vitro culture by qPCR and detection of Ig production by ELISA on day 6 of in vitro culture. ELISA assays were performed using BD Pharmingen ELISA kits for mouse Igs. Plasma cell differentiation was studied in B cells cultured for 4 days by evaluating surface CD138 staining by flow cytometry and mRNA expression levels of Blimp-1 (PRDM-1), XBP-1, and IRF-4 by qPCR.

qPCR.

mRNA was isolated from mouse and human B cells by Trizol, and cDNA was synthesized by Bio-Rad iScript and further used to detect different gene expression using Taqman qPCR. The Taqman reagents for Aicda (Mm01184115_m1), Blimp-1 (Mm00476128_m1), XBP-1 (Mm00457357_m1), IRF-4 (Mm00516431_m1), and Bcl-6 (Mm00477633_m1) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Immunoblotting.

Mouse B cell protein lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Specific proteins were detected using anti-PP2AC, anti-PPP2R1a/1b, and anti–β-actin. Anti-PP2AC Ab (clone 1D6) was purchased from MilliporeSigma. Anti-PPP2R1a/1b Ab was purchased from Cell Signaling (clone 81G5). Anti–β-actin Ab was purchased from MilliporeSigma (clone 4C2).

Immunocytochemistry.

Frozen spleen sections were stained with indicated antibodies per general protocol and evaluated under confocal microscopy by 2 blinded users. For analysis of IgM or IgG deposit in the spleens and IgG deposit in the kidneys, IHC was performed on 10% formalin-fixed spleen tissue (4 μM) sections. Endogenous peroxidase quenching was performed by addition of 3% H2O2, followed by 0.25% pepsin-antigen retrieval. Tissues were subsequently blocked with 1.5% BSA, followed by incubation with HRP-linked anti–mouse IgM (Southern Biotech, catalog 1021-05) and/or anti–mouse IgG (Southern Biotech, catalog 1013-05) and treated with 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (MilliporeSigma). Tissues were imaged under an Olympus BX41 System Microscope.

PP2A phosphatase assay.

B cells were isolated from mouse spleens, and PP2A phosphatase assay was performed as manufactory’s instructions (MilliporeSigma, catalog 17-313). In vitro stimulation was performed at indicated time points (CpG, 3 μg/mL; anti-CD40 Ab, 100 ng/mL; and anti–mouse IgM, 1.3 mg/mL).

Targeted metabolomics analysis.

Metabolites were extracted from cells using 80% methanol (vol/vol). Polar metabolomics profiling (303 metabolites) was performed by using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectroscopy (LC/MS) in the BIDMC mass spectrometry core according to the protocol (46). Once the SRM data were acquired, peaks were integrated in order to generate chromatographic peak areas used for quantification across the sample set. Metabolomics data were analyzed using MetaboAnalyst 4.0 (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/) (47). Briefly, missing metabolite raw intensity values were filled in with the lowest detectable intensity of the respective metabolites, and all raw intensities were normalized to the sum intensity of the respective replicate. Metabolites with ≥ 2-fold changes between groups were identified and subjected to either enrichment analysis or pathway analysis. For joint pathway analysis, metabolites with ≥ 2-fold changes between groups and genes with significant alterations (P < 0.05, 2-tailed t-test) obtained from RNA-seq data were combined for the integrated metabolic pathway analysis.

Transcriptome analysis (RNA-seq).

RNA was extracted from sorted cells (1 × 104) using QIAGEN RNeasy Micro Kit. RNA-seq was performed using the Smart-seq2 platform. Smart-Seq2 libraries were prepared by the Broad Technology Labs and sequenced by the Broad Genomics Platform. Transcripts were quantified by the Broad Technology Labs computational pipeline using Cuffquant version 2.2.1. All RNA-seq data were deposited in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO accession no. GSE144700; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE144700).

Statistics.

Student 2-tailed t test and 2-way ANOVA were applied for statistical analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, although lower P values are indicated in individual figures. In all graphs, data represent mean ± SEM.

Study approval.

For human studies, written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and all studies were approved by the IRB (Committee on Clinical Investigations) at BIDMC. All animal studies were approved by the IACUC at BIDMC.

Author contributions

EM, HL, and GCT designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. WP, MK, SY, VCK, CI, NRR, JCC, SAA, PL, JM, AS, and MGT provided expertise and reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project is funded by NIH NIAID RO1 AI068787 and RO1 AI136924 to GCT. The authors would like to thank Raif S. Geha and Erin Janssen for valuable discussions and intellectual input.

Version 1. 03/12/2020

Electronic publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Copyright: © 2020, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: JCI Insight. 2020;5(5):e130655.https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.130655.

Contributor Information

Esra Meidan, Email: esra.meidan@childrens.harvard.edu.

Hao Li, Email: hli13@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Wenliang Pan, Email: wpan2@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Michihito Kono, Email: m-kono@med.hokudai.ac.jp.

Shuilian Yu, Email: syu3@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Vasileios C. Kyttaris, Email: vkyttari@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Christina Ioannidis, Email: cioannid@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Jose C. Crispin, Email: carlos.crispina@incmnsz.mx.

Sokratis A. Apostolidis, Email: socrates.apostolidis@gmail.com.

John Manis, Email: John.manis@enders.tch.harvard.edu.

Amir Sharabi, Email: isharabiamir@gmail.com.

George C. Tsokos, Email: gtsokos@bidmc.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Bannard O, Cyster JG. Germinal centers: programmed for affinity maturation and antibody diversification. Curr Opin Immunol. 2017;45:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pillai S, Mattoo H, Cariappa A. B cells and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23(6):721–731. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mond JJ, Lees A, Snapper CM. T cell-independent antigens type 2. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:655–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dintzis RZ, Middleton MH, Dintzis HM. Studies on the immunogenicity and tolerogenicity of T-independent antigens. J Immunol. 1983;131(5):2196–2203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blier PR, Bothwell AL. The immune response to the hapten NP in C57BL/6 mice: insights into the structure of the B-cell repertoire. Immunol Rev. 1988;105:27–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1988.tb00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S, Chen L. T lymphocyte co-signaling pathways of the B7-CD28 family. Cell Mol Immunol. 2004;1(1):37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuleihan R, Ramesh N, Geha RS. Role of CD40-CD40-ligand interaction in Ig-isotype switching. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5(6):963–967. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catron DM, Itano AA, Pape KA, Mueller DL, Jenkins MK. Visualizing the first 50 hr of the primary immune response to a soluble antigen. Immunity. 2004;21(3):341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Victora GD, Nussenzweig MC. Germinal centers. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:429–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen CD, Okada T, Tang HL, Cyster JG. Imaging of germinal center selection events during affinity maturation. Science. 2007;315(5811):528–531. doi: 10.1126/science.1136736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luzina IG, et al. Spontaneous formation of germinal centers in autoimmune mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70(4):578–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cappione A, et al. Germinal center exclusion of autoreactive B cells is defective in human systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(11):3205–3216. doi: 10.1172/JCI24179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinuesa CG, Sanz I, Cook MC. Dysregulation of germinal centres in autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(12):845–857. doi: 10.1038/nri2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong EB, Khan TN, Mohan C, Rahman ZS. The lupus-prone NZM2410/NZW strain-derived Sle1b sublocus alters the germinal center checkpoint in female mice in a B cell-intrinsic manner. J Immunol. 2012;189(12):5667–5681. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arkatkar T, et al. B cell-derived IL-6 initiates spontaneous germinal center formation during systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2017;214(11):3207–3217. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diamond B, Katz JB, Paul E, Aranow C, Lustgarten D, Scharff MD. The role of somatic mutation in the pathogenic anti-DNA response. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:731–757. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.003503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wellmann U, Letz M, Herrmann M, Angermüller S, Kalden JR, Winkler TH. The evolution of human anti-double-stranded DNA autoantibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(26):9258–9263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500132102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Domeier PP, et al. IFN-γ receptor and STAT1 signaling in B cells are central to spontaneous germinal center formation and autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2016;213(5):715–732. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zou YR, Diamond B. Fate determination of mature autoreactive B cells. Adv Immunol. 2013;118:1–36. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407708-9.00001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nashi E, Wang Y, Diamond B. The role of B cells in lupus pathogenesis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42(4):543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seshacharyulu P, Pandey P, Datta K, Batra SK. Phosphatase: PP2A structural importance, regulation and its aberrant expression in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;335(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virshup DM. Protein phosphatase 2A: a panoply of enzymes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12(2):180–185. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crispín JC, Apostolidis SA, Finnell MI, Tsokos GC. Induction of PP2A Bβ, a regulator of IL-2 deprivation-induced T-cell apoptosis, is deficient in systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(30):12443–12448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103915108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katsiari CG, Kyttaris VC, Juang YT, Tsokos GC. Protein phosphatase 2A is a negative regulator of IL-2 production in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(11):3193–3204. doi: 10.1172/JCI24895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sunahori K, Juang YT, Tsokos GC. Methylation status of CpG islands flanking a cAMP response element motif on the protein phosphatase 2Ac alpha promoter determines CREB binding and activity. J Immunol. 2009;182(3):1500–1508. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sunahori K, Nagpal K, Hedrich CM, Mizui M, Fitzgerald LM, Tsokos GC. The catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2Ac) promotes DNA hypomethylation by suppressing the phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase (MEK)/phosphorylated ERK/DNMT1 protein pathway in T-cells from controls and systemic lupus erythematosus patients. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(30):21936–21944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.467266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juang YT, et al. PP2A dephosphorylates Elf-1 and determines the expression of CD3zeta and FcRgamma in human systemic lupus erythematosus T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181(5):3658–3664. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crispín JC, et al. Cutting edge: protein phosphatase 2A confers susceptibility to autoimmune disease through an IL-17-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2012;188(8):3567–3571. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apostolidis SA, et al. Phosphatase PP2A is requisite for the function of regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(5):556–564. doi: 10.1038/ni.3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao G, et al. B-Cell-Specific Diversion of Glucose Carbon Utilization Reveals a Unique Vulnerability in B Cell Malignancies. Cell. 2018;173(2):470–484.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zonta F, et al. Lyn sustains oncogenic signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia by strengthening SET-mediated inhibition of PP2A. Blood. 2015;125(24):3747–3755. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-619155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Connor CM, Perl A, Leonard D, Sangodkar J, Narla G. Therapeutic targeting of PP2A. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2018;96:182–193. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allman D, Pillai S. Peripheral B cell subsets. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20(2):149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanz I, et al. Challenges and Opportunities for Consistent Classification of Human B Cell and Plasma Cell Populations. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2458. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tellier J, et al. Blimp-1 controls plasma cell function through the regulation of immunoglobulin secretion and the unfolded protein response. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(3):323–330. doi: 10.1038/ni.3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding C, et al. STAT3 Signaling in B Cells Is Critical for Germinal Center Maintenance and Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Murine Models of Lupus. J Immunol. 2016;196(11):4477–4486. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deenick EK, Pelham SJ, Kane A, Ma CS. Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 Control of Human T and B Cell Responses. Front Immunol. 2018;9:168. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caro-Maldonado A, et al. Metabolic reprogramming is required for antibody production that is suppressed in anergic but exaggerated in chronically BAFF-exposed B cells. J Immunol. 2014;192(8):3626–3636. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jang KJ, et al. Mitochondrial function provides instructive signals for activation-induced B-cell fates. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6750. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xing Y, Igarashi H, Wang X, Sakaguchi N. Protein phosphatase subunit G5PR is needed for inhibition of B cell receptor-induced apoptosis. J Exp Med. 2005;202(5):707–719. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slupe AM, Merrill RA, Strack S. Determinants for Substrate Specificity of Protein Phosphatase 2A. Enzyme Res. 2011;2011:398751. doi: 10.4061/2011/398751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghodke-Puranik Y, et al. Lupus-Associated Functional Polymorphism in PNP Causes Cell Cycle Abnormalities and Interferon Pathway Activation in Human Immune Cells. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(12):2328–2337. doi: 10.1002/art.40304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levinson DJ, Chalker D, Arnold WJ. Reduced purine nucleoside phosphorylase activity in preparations of enriched T-lymphocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Lab Clin Med. 1980;96(3):562–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Markert ML. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase deficiency. Immunodefic Rev. 1991;3(1):45–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kauko O, et al. PP2A inhibition is a druggable MEK inhibitor resistance mechanism in KRAS-mutant lung cancer cells. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(450):eaaq1093. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaq1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan M, Breitkopf SB, Yang X, Asara JM. A positive/negative ion-switching, targeted mass spectrometry-based metabolomics platform for bodily fluids, cells, and fresh and fixed tissue. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(5):872–881. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia J, Wishart DS. Web-based inference of biological patterns, functions and pathways from metabolomic data using MetaboAnalyst. Nat Protoc. 2011;6(6):743–760. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.