Abstract

Objective: This study examined the effect of pediatric obesity on executive function and reward-related decision-making, cognitive processes that are relevant to obesogenic behaviors, and evaluated their association with sample (e.g., age, gender, intelligence, and socioeconomic status, SES) and study/task (e.g., categorical/continuous variable, food stimuli) characteristics.

Methods: A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted using Hedge's g effect sizes of published studies from 1960 to 2016, limited to children younger than the age of 21 years without medical comorbidities. Analysis included estimation of heterogeneity (τ2), publication bias (funnel-plot symmetry and fail-safe N), and sensitivity analyses for sample and study/task characteristics.

Results: Across 68 studies with 70 samples, obesity was associated with worse functioning overall (−0.24; 95CI: −0.30 to −0.19; p < 0.001) and for each component process (attention, switching, inhibition, interference, working memory, reward, delay of gratification: −0.19 to −0.38; p's < 0.017), except trait impulsivity (−0.06; 95CI: −0.18 to 0.07). Deficits increased with age and female composition of the sample for inhibition (p = 0.002). No other characteristics moderated effect of obesity.

Conclusions: Small-to-moderate negative associations with obesity were observed for executive and reward-related performance, but not on reported impulsivity in studies with children younger than the age of 21 years. These results were not moderated by IQ, SES, and study/task characteristics. Age and gender moderated association with inhibition, with a larger obesity-related deficit in older and predominantly female samples. These results suggest cognitive and demographic intervention targets for prevention and mitigation of obesogenic behavior.

Keywords: : attention, executive function, IQ, reward, SES

The pediatric obesity epidemic began over 15 years ago,1 with over 20% of adolescents and 17.5% of children currently obese in the United States (body mass index—BMI—above the 95th percentile).2 In addition to increased risk for medical and psychopathological comorbidities during childhood3 and later in adulthood,4,5 pediatric obesity is associated with worse social,6 cognitive,7 and academic outcomes.6,8 Models of obesity point to the centrality of executive and reward-related processes that may serve to promote and maintain obesity through their influence on obesogenic behavior (e.g., consumption of energy dense foods).9,10 In light of the growing literature examining these cognitive functions in pediatric obesity, we conducted a meta-analysis with the goals of drawing definitive conclusions about their status in children with obesity and moderating sociodemographic factors (e.g., socioeconomic status—SES, age, gender).

Executive function subsumes voluntary regulatory processes that enable flexible goal-directed behavior, which in conjunction with reward processing guides decision-making.11 The meta-analysis takes a cognitive neuroscience perspective, which posits that a set of general-purpose control processes enabled by the prefrontal cortex serve to regulate complex cognition.12 Three control processes have been revealed by latent variable analysis13: (a) attending to and holding contextually appropriate stimuli and responses in mind temporarily (indexed by assessments of attention and working memory); (b) inhibiting inappropriate responses (indexed by tasks of inhibition and interference and questionnaires of impulsive traits), and (c) flexibly shifting responses as context changes (indexed by assessments of cognitive flexibility or shifting). These control processes interact with implicit and explicit reward processes associated with affect (i.e., hedonic value or “liking”), learning of reward contingencies, and motivation (i.e., “wanting”)14 in the context of decision-making. The behavioral outcomes of reward-related decision-making are typically measured by delay of gratification and delayed discounting tasks manipulating rewards. These tasks require the integration of control and reward-related processes subserved by connections of the prefrontal cortex with striatal regions.15 Guided by this conceptual framework, our literature search included the italicized terms.

Executive and reward function is associated with both the promotion and maintenance of obesity by influencing both healthy and obesogenic behaviors.9,10 Better inhibitory control has been associated with increased likelihood of completing a planned physical activity or healthy food choice in adults16 and was associated with more fruit/vegetable intake and engagement in physical activity in children.17 Children with better executive function at the end of elementary school were also more likely to maintain a lean body weight at end of junior high.18 Conversely, poor executive abilities in children have been associated with greater snack food intake and sedentary behavior17 and increased risk for maladaptive food behavior (e.g., emotional overeating),19 while increased reward sensitivity in children has been associated with greater intake of fast food and sweetened beverages.20 In addition, worse delay of gratification and self-regulation in early childhood (2 and 4 years) were associated with higher BMIs in later childhood,21 preadolescence,22 and adulthood.23 Prevention and intervention efforts would be served by knowing the magnitude of executive and reward-related decision-making deficits in children and adolescents with obesity and whether these deficits are moderated by sociodemographic factors.

The effect of obesity on executive function appears to be moderated by a variety of demographic factors. Variability in general intelligence, as measured by IQ, and SES are independently associated with risk for pediatric obesity24 and executive dysfunction25–27 and, therefore, have the potential to attenuate or augment the association between obesity and executive deficits. In addition, it is possible that the effect of obesity on executive function changes across development with adolescence representing a particularly vulnerable period of development because the maturation of executive control lags behind gains in reward sensitivity.28 Thus, obesity may further compromise executive abilities during adolescence, leading to a larger adverse effect of obesity on executive functioning in adolescents than in younger children. Understanding the moderating influence of developmental and demographic factors on the effect of obesity is necessary for identifying who is at risk.

The present study aims to comprehensively quantify the magnitude of impairment in executive and reward function in pediatric obesity by conducting a meta-analysis of studies published through December 2016 that examined those cognitive functions in children younger than the age of 21 years without other health comorbidities. Since the previously published meta-analysis29 (inclusion July 2012) focusing on impulsivity in pediatric obesity (i.e., inhibitory control and reward-related decision-making), there have been more than twice as many additional studies that have been published. The present study examines whether their observed pattern of obesity-related deficits for inhibition and reward-related decision-making29 are replicated and extend to other control processes (e.g., cognitive flexibility, working memory). In addition, we examined the effect of important moderators through sensitivity analyses, including sociodemographic factors (e.g., age and gender, SES), IQ, and study-design characteristics. Together, we sought to provide a comprehensive view of the status of executive and reward function in pediatric obesity.

Methods

This study followed the guidelines outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.30

Literature Search

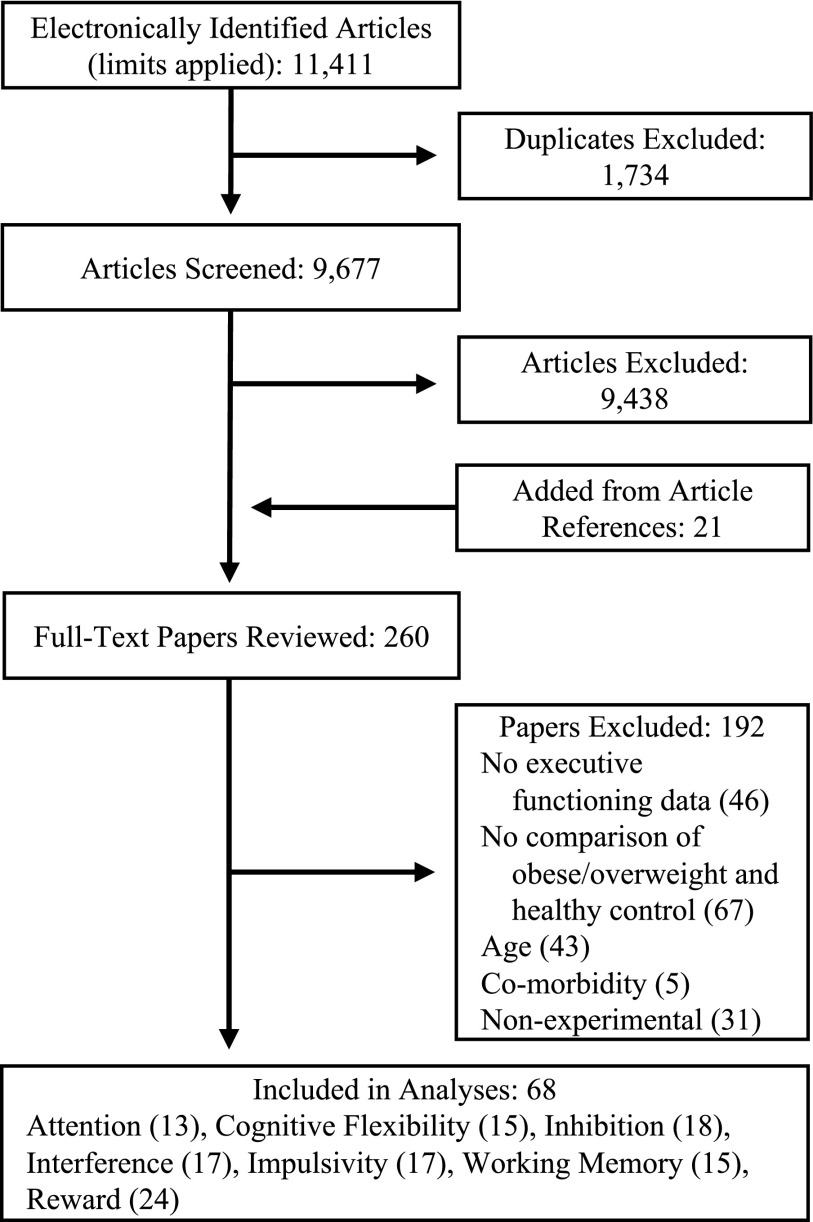

Our search used PubMed (from 1960 to 2016), PsychInfo (from 1978 to 2016), and Academic Search Premier (from 1975 to 2016) and included following search terms attention, executive function, cognitive control, inhibition, working memory, switching, cognitive flexibility, impulsivity, delayed discounting, reward, and delay of gratification in conjunction with obesity, obese, body mass index, overweight, weight, and adiposity. Search terms for cognitive functioning were derived from common terminology related to executive and reward processes in addition to the tasks used to assess them (examples of search terms are italicized in Introduction). The search used the limits youth, adolescents, child/children, pediatric, and human and yielded 9677 unique studies. Figure 1 presents a graphic of the decision process (Supplementary Data for an example of the electronic search strategy; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/chi).

FIG. 1.

Flowchart depicting results and method the systematic review.

Titles of studies were screened according to the following exclusion criteria: (a) not written or translated to English; (b) participant older than the age of 21years; (c) inclusion of participants with genetic syndrome associated with obesity; (d) inclusion of participants diagnosed with psychopathological disorder (e.g., eating disorder or anxiety) or medical comorbidity (e.g., metabolic syndrome or type II diabetes); and (e) report of only latent variable for executive/reward function. Full texts were reviewed for both the exclusion criteria and the following inclusion criteria: (a) empirical study; (b) participant sample included both participants with healthy weight (>5% BMI percentile <85%) and overweight/obesity (BMI percentile ≥85%); and (c) executive or reward functioning and adiposity were assessed concurrently. A total of 68 studies met criteria for inclusion, many of which assessed multiple processes of executive and reward function (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Study | Sample size | Study design | Adiposity criteria | Mean age (range) | Gender (%M) | Executive measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #+Alarcon et al.51 | 152 | Cat | BMI.p (>85th) | 14.1 (12–17) | 56 | Working Memory: 2-Back Task |

| ^Batterink et al.54 | 35 | Cont | BMI | 15.7 (NA) | 0 | Inhibition: Go/No-Go |

| Bauer et al.55 | 69 | Cat | BMI.p (>85th) | 16.4 (14–20) | 52 | Interference: Stroopb |

| Bauer et al.56 | 158 | Cat | BMI.p (>85th) | 15.6 (NA) | 0 | Attention: Sustained Attention Task |

| Impulsivity: Barratt Impulsiveness Scalea | ||||||

| Working Memory: Spatial Memory Task | ||||||

| #Blanco-Gomez et al.57 | 424 | Cat | BMI.p (>95th) | 8.5 (6–10) | 49 | Attention: Children's Colored Trails Test 1 |

| Switching: Children's Colored Trails Test 2 | ||||||

| 220 | 56.6 | Inhibition: Five Digit Test | ||||

| Switching Five Digit Test (Flexibility & Switching)a | ||||||

| Bonato & Boland58 | 40 | Cat | Triceps (>1SD) | 10.0 (8–11) | 50 | Reward: Candy and Non-Edible Choice to Wait |

| ^Bonato & Boland59 | 20 | Cat | Triceps (>1SD) | 10.0 (8–11) | 50 | Interference: Incompatibility (ACC & RT)a |

| ^Bourget & White60 | 36 | Cat | OW.p (>110%) | 7.14 (5–9) | 0 | Reward: Food and Toy Wait Time |

| #^Breat et al.61 | 109 | Cat | Adjusted BMI | 13.4 (10–18) | 45 | Impulsivity: Matching Familiar Figure Test |

| ^Bruce et al.62 | 59 | Cont | BMI.p (>85th) | 10.3 (8–12) | 53 | Reward: Points Saved |

| #Bruce et al.63 | 20 | Cat | BMI | 11.9 (10–14) | 45 | Impulsivity: Eysenck 16 Junior Questionnaire |

| #+Buck et al.64 | 77 | Cont | BMI.z | 9.3 (7–12) | 55 | Interference: Stroop Color and Word Test Children's Version |

| +Cserjesi et al.65 | 24 | Cont | BMI (>24) | 12.3 (NA) | 100 | Attention: (1) D2 Attention Endurance Test; (2) Digit Span Forward |

| Switching: (1) Semantic Fluency; (2) Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (Perseverative Errors and Responses)a | ||||||

| Working Memory: Digit Span Backward | ||||||

| #De Decker et al.20 | 443 | Cont | BMI.z | 8.9 (5–11) | 51 | Impulsivity: Behavioral Activation Scale |

| #Delgado-Rico et al.66 | 63 | Cat | BMI | 14.2 (12–17) | 40 | Switching: D-KEFs Stroop Switching |

| Interference: D-KEFs Stroop | ||||||

| Impulsivity: (1) Sensitivity to Reward; (2) UPPS-P (all subscales)a | ||||||

| Delgado-Rico et al.67 | 52 | Cat | BMI (IOTF) | 14.1 (12–17) | 33 | Reward: Risk Gains Task |

| #^Duckworth et al.18 | 105 | Cont | BMI.z | 10.6 (NA) | 48 | Impulsivity: statistical composite |

| ^Evans et al.68 | 244 | Cont | BMI | 9.2 (NA) | 55 | Reward: Food Wait Time |

| #+^Fields et al.69 | 37 | Cat | BMI.p (>95th) | 17.3 (14–19) | 58 | Reward: Question Based Delay Discounting |

| #+Fields et al.70 | 61 | Cat | BMI.p (>85th) | 15.0 (14–16) | 44 | Attention: Continuous Performance Test |

| Inhibition: Stop Signal Test | ||||||

| Reward: Question Based Delay Discounting | ||||||

| Groppe and Elsner71 | 1657 | Cont | BMI SDS | 8.3 (6–11) | 48 | Switching: Cognitive Flexibility Task |

| Interference: Fruit Stroop Task | ||||||

| Reward: (1) Candy and Toy Choice to Wait; (2) Hungry Donkey Task | ||||||

| Working Memory: Digit Span Backward | ||||||

| +Guerrieri et al.72 | 78 | Cat | BMI norms | 9.0 (8–10) | 58 | Inhibition: Stop Signal Test |

| Reward: Door Opening Task | ||||||

| Gunstad et al.73 | 451 | Cat | BMI.p (>85th) | 12.5 (6–19) | 51 | Switching: (1) Semantic Fluency; (2) Trail-Making Test B |

| Working Memory: Digit Span Backward | ||||||

| Hjorth et al.74 | 744 | Cat | BMI.p (>85th) | 9.9 (9–11) | 51 | Attention: (1) D2 Attention Endurance Test |

| Hofmann et al.75 | 58 | Cat | BMI.p (>97th) | 13.6 (10–18) | 59 | Impulsivity: Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-15 |

| Huang et al.76 | 525 | Cont | BMI | 13.0 (NA) | 48 | Interference: Flanker (ACC & RT)a |

| Hughes et al.77 | 187 | Cont | BMI.z | 4.8 (NA) | 52 | Inhibition: Children's Behavior Questionnaire-Effortful Control |

| Reward: Food and Gift Delay of Gratification | ||||||

| ^Johnson et al.78 | 142 | Cont | Skinfold | 8.6 (6–11) | 45 | Reward: Food and Toy Items Delayed |

| #+Kamijo et al.79 | 126 | Cat | BMI.p (>85th) | 8.9 (7–9) | 50 | Inhibition: Go/No-Go |

| #+Kamijo et al.80 | 74 | Cat | BMI.p (>95th) | 9.0 (NA) | 49 | Inhibition: Go/No-Go |

| #+Kamijo et al.81 | 74 | Cat | BMI.p (>95th) | 8.9 (7.9–9.9) | 54 | Inhibition: Flankerb |

| Kulendran et al.82 | 103 | Cat | BMI.p (>85th) | 14.3 (10–17) | 38 | Inhibition: Stop Signal Test (SSRT, SSD, errors)a |

| Reward: Monetary Temporal Discounting Task | ||||||

| #Levitan et al.83 | 193 | Cont | BMI.z | 4.0 (NA) | 53 | Inhibition: Stop Signal Test |

| +Li et al.84 | 2519 | Cont | BMI.p (>85th) | 12.0 (8–16) | 52 | Working Memory: Digit Span Backward |

| Lu et al.85 | 87 | Cont | BMI | 12.7 (NA) | 55 | Reward: Delay Discounting Task |

| #+^Maayan et al.86 | 91 | Cat | BMI.p (>95th) | 17.4 (14–21) | 39 | Attention: (1) WRAML index; (2) Trail-Making Test A |

| Switching: Trail-Making Test B | ||||||

| Interference: Stroop Color Word Number Correct | ||||||

| Working Memory: WRAML index | ||||||

| Mata et al.87 | 54 | Cat | BMI (IOTF) | 15.4 (12–18) | 39 | Reward: Risk Gains Task |

| Matton et al.88 | 579 | Cont | Adjusted BMI | 15.7 (14–19) | 40 | Impulsivity: Sensitivity to Reward (SRSPQ & Behavioral Activation System)a |

| Meule et al.89 | 122 | Cont | BMI | 13.6 (10–18) | 48 | Impulsivity: Barratt Impulsiveness Scalea |

| #Miller et al.90 | 133 | Cont | BMI.p | 2.8 (NA) | 50 | Reward: Fooda and Toya Delay of Gratification |

| Mond et al.91 | 9415 | Cont | BMI (IOTF) | 6.0 (4–8) | 52 | Working Memory: Sentences |

| #Moreno-Lopez et al.92 | 52 | Cat | BMI (IOTF) | 14.2 (12–17) | 33 | Interference: D-KEFs Stroop |

| Impulsivity: (1) SPSRQ; (2) UPPS-P (all subscales)a | ||||||

| ^Nederkoorn et al.93 | 63 | Cat | BMI | 13.7 (12–15) | 40 | Impulsivity: Behavioral Activation Scalea |

| Inhibition: Stop Signal Task | ||||||

| Reward: Door Opening Task | ||||||

| ^Nederkoorn et al.95 | 26 | Cont | OW.p (>120%) | 9.3 (NA) | 35 | Inhibition: Stop Signal Task |

| ^Nederkoorn et al.94 | 89 | Cat | OW.p (>120%) | 8.1 (7–9) | 45 | Inhibition: Stop Signal Task Food and Toy |

| Niemiro et al.96 | 28 | Cat | BMI.p (>85th) | 8.9 (8–10) | 100 | Other: Woodcock-Johnson III Executive Processing |

| Parisi et al.97 | 318 | Cat | BMI.p (>85th) | 9.9 (6–13) | 46.9 | Attention: (1) Kauffman Attention Factor; (2) SDAG |

| ^Pauli-Pott et al.98 | 111 | Cont | BMI SDS | 11.1 (7–15) | 43 | Attention: TAP |

| #+Pearce et al.52* | 59 | Cat | BMI.p (>95th) | 11.7 (7–18) | 41 | Attention: 1-Back Task |

| Inhibition: Stop Signal Task (SSRT & SSD)a | ||||||

| Reward: BART (Pops and Pumps)a | ||||||

| #+Pearce et al.52* | 59 | Cat | BMI.p (>95th) | 11.7 (7–18) | 41 | Working Memory: 2-Back Task |

| Continued | 112 | 12.5 (7–18) | 54 | Switching: BRIEF Switch | ||

| Inhibition: BRIEF (Inhibit & Emotional Control subscales)a | ||||||

| Working Memory: BRIEF | ||||||

| Other: BRIEF (Initiate, Plan and Organization, Organization of Materials, & Monitoring subscales)a | ||||||

| #+Pontifex et al.99 | 204 | Cont | Total Fat | 8.8 (7–10) | 53 | Switching: Switch Task (Heterogeneous and Homogeneous)a |

| Interference: Flankerb | ||||||

| #Ross et al.100 | 130 | Cat | BMI (>30) | 19.5 (15–21) | 42 | Switching: Trail-Making Test B-A |

| Interference: Stroop Interference | ||||||

| Working memory: (1) WISC Index; (2) Letter-Number Sequencing | ||||||

| Other: (1) Category Test; (2) Tower of London | ||||||

| Ross et al.101 | 238 | Cont | BMI.z | 15.6 (14–17) | 56 | Reward: (1) Iowa Gambling Task; (2) Risky Choices (Dice and Cup Tasks)a |

| #Scholten et al.102 | 1377 | Cat | BMI.z | 10.2 (8–12) | 51 | Impulsivity: Temperament in Middle Childhood Questionnaire |

| Reward: Door Opening Task | ||||||

| Schwartz et al.103 | 983 | Cont | Visceral Fat | 15.0 (12–18) | 49 | Attention: Digit Span Forward |

| Switching: Semantic Fluency | ||||||

| Interference: Stroop | ||||||

| Working Memory: (1) Digit Span Forward; (2) Self Ordered Pointing | ||||||

| Sigal and Adler104 | 64 | Cat | OW.p (>125%) | NA (8–13) | 100 | Reward: Food and Non-Food Weight Time |

| Skoranski et al.105 | 60 | Cat | BMI.p (>85th) | 12.8 (7–17) | 38 | Interference: Simonb |

| ^Sobhany and Rogers106 | 112 | Cat | Triceps (>90th) | 4.8 (3–5) | 49 | Reward: Food and non-Food Choice to Wait |

| 134 | 8.6 (6–13) | 49 | Reward: Food and non-Food Choice to Wait | |||

| ^van den Berg et al.107 | 331 | Cat | BMI SDS | 9.1 (6–13) | 55.3 | Impulsivity: SRSPQ |

| Velders et al.108 | 1621 | Cont | BMI SDS | 4.0 (NA) | 51 | Switching: BRIEF Switch |

| Inhibition: BRIEF Inhibit | ||||||

| ^Verbeken et al.109 | 82 | Cat | Adjusted BMI | 11.8 (10–14) | 40 | Interference: Test of Everyday Attention for Children-Opposite Worlds |

| Inhibition: Stop Signal Task | ||||||

| Reward: (1) Maudsley Index of Childhood Delay Aversion; (2) Door Opening Task | ||||||

| Other: Five Digit Test Circle Drawing | ||||||

| ^Verbeken et al.110 | 438 | Cont | Adjusted BMI | 12.0 (10–15) | 47.5 | Reward: Behavioral Activation Scale Drive |

| Verbeken et al.111 | 132 | Cont | BMI.p (>85th) | 12.4 (11–16) | 45.5 | Reward: Hungry Donkey Task |

| +^Verdejo-Garcia et al.112 | 61 | Cat | BMI (IOTF) | 14.9 (13–16) | 61 | Switching: (1) Trail-Making Test B-A; (2) Five Digit Test |

| Interference: (1) Stroop; (2) Five Digit Test | ||||||

| Impulsivity: (1) SPSRQ; (2) UPPS-P (all subscales)a | ||||||

| Reward: (1) Delay Discounting; (2) Iowa Gamboling Task | ||||||

| Working Memory: Letter-Number Sequencing | ||||||

| Verdejo-Garcia et al.113 | 80 | Cat | BMI (IOTF) | 15.2 (12–18) | 39 | Reward: SRSPQ |

| #Wirt et al.114 | 496 | Cat | BMI.p (>90th) | 7.0 (5–9) | 49.8 | Inhibition: TAP Go/No-Go (total and errors)a |

| #Wirt et al.115 | 445 | Cont | BMI.p (>90th) | 7.0 (5–9) | 49.8 | Attention: TAP |

| Switching: TAP | ||||||

| Inhibition: TAP Go/No-Go | ||||||

| #+Yau et al.116 | 60 | Cat | BMI.p (>95th) | 17.4 (14–20) | 40 | Switching: (1) Trail-Making Test B; (2) Wisconsin Card Sorting Task Perseverative Errors |

| Interference: Stroop | ||||||

| Working Memory: WRAML index | ||||||

| Zamzow et al.50 | 2841 | Cat | BMI | NA (8–19) | NA | Attention: Continuous Performance Test |

| Working Memory: Letter N-Back | ||||||

| Other: Penn Conditional Exclusion Task |

Value in parentheses after adiposity measure indicate cutoff used to identify overweight/obesity. Leading numbers indicate reference number.

Studies included in SES model.

Studies included in IQ model.

Studies also included in Thamotharan et al. (2013).

Measures combined to create an aggregated effect.

Interference score calculated by hand (incongruent scores - congruent scores).

Included in search as a study under submission and was later published.

BMI, body mass index; BMI.p, percentile; BMI.z, Z-score; BMI SDS, standardized; IOTF, International Obesity Task Force cutoffs used; Triceps, triceps skin-fold thickness; OW.p, percent overweight.

Coding and Data Extraction

All studies were coded by authors AP and CL with disagreements or errors resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

See Supplementary Data for description of study reported statistics. In the event that obese and overweight groups were reported separately, pooled means and standard deviations were used to create a single overweight/obese group. Effects were categorized into one of seven cognitive process: (a) Attention: performance on sustained attention tasks resulting in individual (e.g., Continuous Performance Test) or composite scores (e.g., Kauffman Attention Factor); (b) Cognitive Flexibility/Switching: performance-based measures of verbal fluency, perseveration (e.g., Wisconsin Card Sorting Task), and switching (e.g., Trail-Making Test B); (c) Inhibition: performance on response inhibition (e.g., Go-No/Go, Stop Signal Task); (d) Interference: performance on interference tasks (e.g., Flanker, Stroop); (e) Trait Impulsivity: parental or self-report questionnaires assessing everyday impulsivity (e.g., UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale or Behavioral Activation Scale)–while these behaviors reflect inhibitory and reward function, they were separated due to evidence for the independence of impulsive traits from actions (i.e., inhibition) and choices (i.e., reward)31; (f) Working Memory: performance on working memory tasks (e.g., span tasks, N-back task); (g) Reward: performance on delay discounting, delay of gratification, and reward-related risk taking tasks (e.g., Door Opening Task); (h) Other: tasks related to planning (e.g., Tower of London) or assessments of general executive functioning (e.g., Woodcock–Johnson Executive Processing). For study and task details see Table 1.

Data Analysis

All data analyses were completed using R.32 Study results were converted to Hedge's g,33 with negative effects indicating worse performance in the obese/overweight group or with greater adiposity. Random effect models, using a restricted maximum likelihood estimator and inverse variance weights, were used to estimate the effect of obesity on executive and reward function overall and for each component processes model.34 Although Cochrane's Q and the I2 statistic are commonly used to classify heterogeneity, both have been shown to increase with the number and size of studies in the model.35,36 Therefore, this study used predication intervals, which estimate the variability of the true effect of obesity,37,38 to estimate heterogeneity because they are calculated from τ2 (i.e., between study random variance), which does not systematically vary with the number or size of the studies model. Publication bias was assessed through funnel plot asymmetry using Egger's regression test,39 however, in the presence of heterogeneity, caution was taken when interpreting funnel plots because asymmetry may be attributable to methodological differences in studies, true heterogeneity due to differences in study characteristics, or artifact due to sampling variation in addition to publication bias.40,41 A weighted fail-safe N (FSN; i.e., file drawer problem) was used to assess the stability of findings such that a FSN greater than 5k + 10 (k: number of effects in model) represents a high tolerance to unpublished null findings.42

Sensitivity analyses used mixed effects metaregression models for the following characteristics: (a) Mean age of the sample; (b) Gender composition of the sample (percent male); (c) the effect of adiposity on IQ (Hedge's g estimate); and (d) the effect of adiposity on SES (Hedge's g estimate); (e) Study Design, which was coded as continuous for studies assessing correlation with adiposity and categorical for studies assessing adiposity through group differences; (f) Experimental Assessments, which was included when clusters of studies used the same or similar tasks and was included for Cognitive Flexibility/Switching, Inhibition, Interference, Working Memory, and Reward-Related Decision-Making models; and (g) Food Stimuli, which was included for Delay of Gratification tasks that characterized the delayed rewards as food versus nonfood.

Results

A total of 70 unique samples, extracted from 68 studies, were used in these analyses. Twenty of the 68 studies were also included by the previous meta-analysis,29 while three studies included in that article were excluded due to meeting our exclusion criteria (report of only latent variables, medical comorbidities, or existing conditions). The number of effects sizes extracted from each study ranged from 1 to 14, while study samples sizes ranged from 20 to 9415 participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Model Characteristics

| Model | Age | Gender (%M) | Studies included | Effects included | Participants | Samplea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive Composite | 11.3 | 48.1 | 70 | 149 | 30,359 | 57,800 |

| Attention | 12.1 | 46.6 | 12 | 15 | 6259 | 6692 |

| Switching | 12.3 | 52.5 | 14 | 19 | 6137 | 7157 |

| Inhibition | 9.7 | 44.8 | 18 | 19 | 4070 | 4159 |

| Interference | 13.2 | 46.4 | 16 | 17 | 4208 | 4269 |

| Impulsivity | 12.8 | 43.9 | 17 | 20 | 4160 | 4326 |

| Working memory | 13.5 | 48.9 | 15 | 17 | 18,713 | 19,826 |

| Reward | 11 | 49.1 | 25 | 36 | 5268 | 8048 |

The Overall model contains all executive process and reward models in addition to studies falling in the Other category (Studies = 6; Participants = 3323).

Total sample size for models counts multiple measures from same study separately.

Random Intercept Models

IQ and SES

A total of 15 (22%) and 25 (37%) studies reported data on intelligence and SES, respectively (Table 3). Adiposity had a significant small negative effect for IQ and SES. Both models showed wide prediction intervals indicating nontrivial heterogeneity, likely due to differences in measurement across studies. There was no funnel plot asymmetry and both models showed the FSN's above the cutoff for high tolerance of unpublished null findings. Together, these findings indicate that greater adiposity was associated with lower intelligence and lower SES, however, the prediction interval indicates that the true effect varies substantially.

Table 3.

Model Results

| Model statistics | Heterogeneity estimates | Model bias | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | β (95% CI) | Z | p | τ2 | 95% PI | Egger's Z | p | FSN | |

| Demographic models | |||||||||

| IQ | 15 | −0.30 (−0.51 to −0.09) | −2.79 | 0.005** | 0.124 | −1.10 to 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.865 | 96 |

| SES | 25 | −0.39 (−−0.57 to −0.20) | −4.05 | <0.001*** | 0.183 | −1.30 to 0.52 | −−1.30 | 0.194 | 520 |

| Executive models | |||||||||

| Overall model | 149 | −0.24 (−0.30 to −0.19) | −8.43 | <0.001*** | 0.083 | −0.81 to 0.33 | −4.75 | <0.001*** | 6976 |

| Attention | 15 | −0.19 (−0.30 to −0.08) | −3.29 | 0.001** | 0.026 | −0.58 to 0.18 | −2.32 | 0.020* | 101 |

| Switching | 19 | −0.21 (−0.32 to −0.11) | −4.12 | <0.001*** | 0.025 | −0.56 to 0.14 | −2.65 | 0.008** | 155 |

| Inhibition | 19 | −0.39 (−0.51 to −0.26) | −6.10 | <0.001*** | 0.034 | −0.80 to 0.02 | −−3.96 | <0.001*** | 226 |

| Interference | 17 | −0.28 (−0.50 to −0.05) | −2.38 | 0.017* | 0.179 | −1.22 to 0.66 | −0.74 | 0.460 | 101 |

| Trait impulsivity | 20 | −0.06 (−0.18 to 0.07) | −0.94 | 0.349** | 0.046 | −0.53 to 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.498 | 10 |

| Working memory | 17 | −0.20 (−0.32 to −0.07) | −3.13 | 0.002 | 0.045 | −0.67 to 0.27 | −3.26 | 0.001** | 85 |

| Reward | 36 | −0.25 (−0.36 to −0.15) | −4.86 | <0.001*** | 0.057 | −0.75 to 0.24 | −2.51 | 0.012* | 282 |

| Delay of gratification | 18 | −0.25 (−0.36 to −0.13) | −4.29 | <0.001*** | 0.021 | −0.25 to 0.08 | −2.52 | 0.012* | 74 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

CI, confidence interval; FSN, Fail-Safe N; PI, prediction interval.

Overall and component process models

There was a significant small negative effect of obesity in the Overall model, indicating worse functioning in children and adolescents with obesity, regardless of component process. Given the wide prediction interval, significant funnel plot asymmetry may not reflect true publication bias but rather systematic heterogeneity across studies, such as cognitive process assessed. The FSN far exceeded the cutoff, indicating that the model was robust to potential unpublished or null findings.

In light of evidence for heterogeneity of effects associated with obesity, separate models were used to assess each cognitive process. Given too few studies, the “Other” category was not examined in a separate model. All processes except Trait Impulsivity showed small negative effects of adiposity, indicating that greater adiposity was associated with worse functioning. Thus, Trait Impulsivity was not included in further analyses. Prediction intervals for Attention, Cognitive Flexibility/Switching, and Inhibition show a distribution of true effects that range from large/moderate negative effects of obesity to negligible positive effects. Interference, Reward-Related Decision-Making, and Working Memory, however, had prediction intervals that extended into small/moderate positive effects. Attention, Cognitive Flexibility/Switching, Inhibition, Working Memory, and Reward-Related Decision-Making all showed evidence of funnel plot asymmetry, however, heterogeneity seen in the predication intervals indicate that there may be study-level differences driving the asymmetry. The majority of the models were robust to potentially unknown null data with only Working Memory and Delay of Gratification showing FSN values that did not meet the cutoff, indicating that new or unpublished null results may affect the strength of the effect of adiposity on those processes. In sum, these models provide evidence for three important findings: first, pediatric obesity is associated with an overall deficit; second, pediatric obesity has a significant negative effect on all component processes except Trait Impulsivity; and third, the prediction intervals indicate that although the effect of pediatric obesity was negative, there may be important differences across studies that influence this effect.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sociodemographic, study design, and experimental assessment characteristics were independently examined to determine whether they moderated the observed significant negative effects of obesity (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity Results

| Model statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | β (95% CI) | Z | p | |

| Age | ||||

| Overall model | 145 | −0.001 (−0.02 to 0.01) | −0.18 | 0.860 |

| Attention | 14 | −0.03 (−0.07 to 0.01) | −1.72 | 0.086† |

| Switching | 19 | −0.02 (−0.04 to 0.01) | −1.27 | 0.204 |

| Inhibition | 19 | −0.04 (−0.07 to −0.02) | −3.11 | 0.002** |

| Interference | 17 | 0.02 (−0.05 to 0.09) | 0.53 | 0.595 |

| Working memory | 16 | −0.02 (−0.06 to 0.02) | −1.00 | 0.316 |

| Reward | 35 | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.02) | −0.39 | 0.693 |

| Gender (% Male) | ||||

| Overall model | 146 | −0.002 (−0.01 to 0.003) | −0.76 | 0.448 |

| Attention | 14 | 0.003 (−0.01 to 0.01) | −0.74 | 0.458 |

| Switching | 19 | −0.01 (−0.02 to 0.003) | −1.43 | 0.153 |

| Inhibition | 19 | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.03) | 3.06 | 0.002** |

| Interference | 17 | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | −0.64 | 0.525 |

| Working memory | 16 | 0.01 (−0.004 to 0.01) | 1.13 | 0.259 |

| Reward | 36 | −0.002 (−0.01 to 0.01) | −0.36 | 0.717 |

| Study design and indexa | ||||

| Overall model | 149 | −0.06 (−0.18 to 0.05) | −1.1 | 0.273 |

| Attention | 15 | −0.16 (−0.40 to 0.08) | −1.12 | 0.196 |

| Switching | 19 | −0.10 (−0.32 to 0.11) | −0.95 | 0.342 |

| Inhibition | 19 | −0.16 (−0.40 to 0.07) | −1.37 | 0.172 |

| Interference | 17 | −0.16 (−0.65 to 0.33) | −0.65 | 0.515 |

| Working memory | 17 | −0.29 (−0.48 to −0.11) | −3.05 | 0.002** |

| Reward | 36 | −0.08 (−0.29 to 0.13) | −0.71 | 0.477 |

| Food stimulib | ||||

| Delay of Gratification | 18 | −0.10 (−0.34 to 0.14) | −0.82 | 0.411 |

| IQ | ||||

| Overall model | 45 | −0.01 (−0.31 to 0.29) | −0.09 | 0.931 |

| Attention | 8 | 0.19 (−0.58 to 0.96) | 0.48 | 0.633 |

| Switching | 9 | 0.67 (−0.22 to 1.54) | 1.46 | 0.144 |

| Interference | 7 | 0.41 (−2.22 to 3.04) | 0.31 | 0.758 |

| Working memory | 8 | 0.10 (−0.44 to 0.63) | 0.35 | 0.724 |

| SES | ||||

| Overall model | 58 | −0.09 (−0.31 to 0.13) | −0.79 | 0.428 |

| Attention | 6 | 0.76 (−0.48 to 2.00) | 1.2 | 0.229 |

| Switching | 10 | −0.46 (−1.28 to 0.35) | −1.12 | 0.264 |

| Inhibition | 9 | 0.02 (−0.54 to 0.58) | 0.07 | 0.945 |

| Interference | 8 | −0.87 (−2.30 to 0.57) | −1.18 | 0.237 |

| Working memory | 7 | −0.10 (−0.42 to 0.23) | −0.56 | 0.574 |

| Reward | 6 | 0.25 (−0.68 to 1.18) | 0.53 | 0.595 |

p < 0.10.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Reference level is continuous.

Reference level is no food stimuli.

Attention

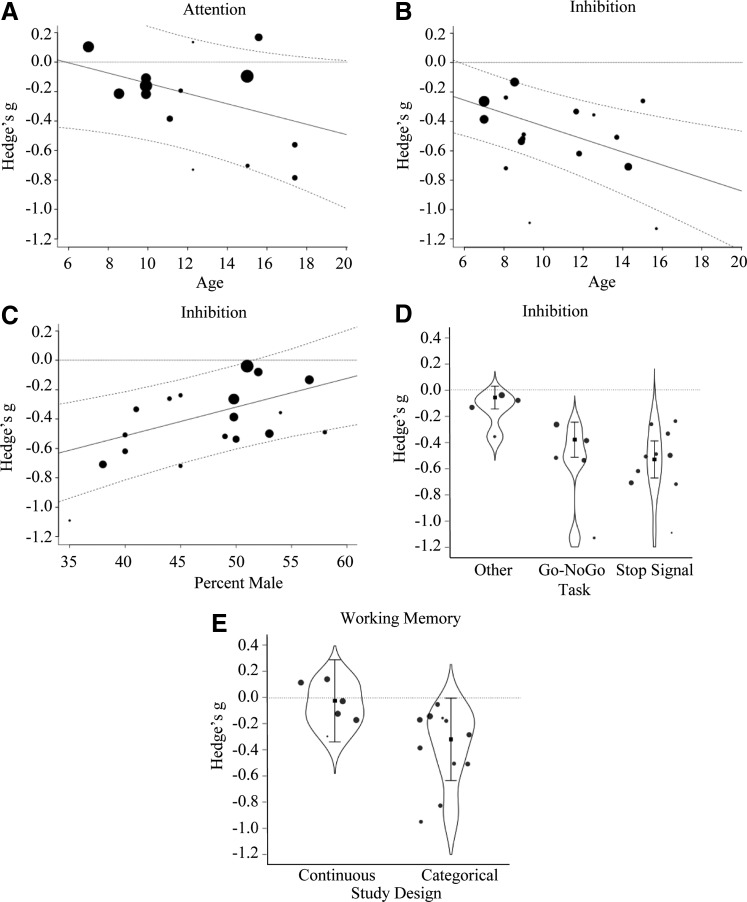

A marginally significant effect of Age indicated that higher mean sample age was associated with more negative effects of adiposity (Fig. 2A). Thus, deficits in attention increased for samples with older children with obesity. No other moderators were significant.

FIG. 2.

These plots depict significant moderators of the effect of obesity on executive abilities with the moderator Age shown in A and B, sample composition in C, Task Type in D, and Study Design in E. The size of the points on the graphs relate to the contribution or weight of that study in the model. The dotted lines reflect predicted marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals.

Inhibition

A significant effect of Age indicated that higher mean sample age was associated with more negative effects of adiposity (Fig. 2B). In addition, a significant effect of Gender indicated that a higher composition of males in a sample was associated with less negative effects of adiposity (Fig. 2C). Although Study Design was not significant, there was an effect of Experimental Assessment (Qmoderator (2) = 37.27, p < 0.001). Studies assessing response inhibition with performance measures (Go/No-Go task: n = 5; β = −0.32, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001 and stop signal task: n = 10; β = −0.47, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001; no difference between tasks, p = 0.129) showed greater negative effects than questionnaire-based assessments (Fig. 2D). Together, these results indicate that older children and females were more vulnerable to the negative effects of obesity and that task performance was more sensitive to the effect of obesity on inhibition than behavioral reports. No other moderators were significant.

Working memory

A significant effect of Study Design indicated that using a categorical rather than a continuous study design resulted in larger negative effects (Fig. 2E). No other moderators were significant, including differences in Experimental Assessments (span-based versus other tasks; p = 0.158).

Remaining models

No moderators were significant for Cognitive Flexibility/Switching, Interference, Reward-Related Decision-Making, or Delay of Gratification models. Similarly, there were no differences between Experimental Assessments in models for Cognitive Flexibility/Switching (trail-making test versus fluency or questionnaire measures; p = 0.102), Interference (Stroop versus Flanker or Simon tasks versus other tasks; p = 0.690), nor Reward-Related Decision-Making (delay of gratification versus risk-taking tasks versus delay discounting; p = 0.147). In addition, there was no effect of Food Stimuli for Delay of Gratification (p = 0.411), indicating that food rewards did not impact Reward-Related Decision-Making differently from nonfood rewards.

Discussion

Small-to-moderate impairments were associated with pediatric obesity for executive and reward-related performance but not trait impulsivity, with larger inhibitory deficits in older and predominantly female samples. Although obesity was associated with lower IQ and SES, these variables did not moderate the observed effects. Together, these findings replicate those of the previous meta-analysis29 and extend the scope of the negative effects of obesity to include additional executive processes and potential moderators. Our results suggest cognitive and demographic targets for intervention and prevention of obesity.

The present findings provide a comprehensive view of the current status of executive and reward deficits in pediatric obesity. Our findings replicate inhibitory and reward-related decision-making deficits in pediatric obesity, but found no evidence for differences for parental/self-report measures of impulsivity. This indicates that obesity was associated with more impulsive actions and decisions, but not impulsive personality traits.31 Beyond replication, our findings showed working memory and cognitive flexibility/shifting deficits associated with obesity. In addition, the present study showed attention deficits associated with obesity while the previous meta-anlysis29 did not, perhaps due to increased power after including the seven studies published since 2012. Despite replication, the present effect sizes were slightly smaller than those reported previously,29 potentially due to the inclusion of double the number of included studies, studies examining a wider range of executive functions, or the strict exclusion of samples with medical comorbidities. Nevertheless, largely consistent findings across these two meta-analyses underscore the stability of deficits for inhibitory and reward function and, therefore, their importance in mediating behaviors that promote obesity in children and adolescents.

Sensitivity analysis revealed age and gender as important moderators of the strength of the associations between obesity and executive and reward functioning, which has implications for intervention or prevention efforts. The performance gap between children with and without obesity was larger for older than younger children on inhibition tasks and marginally so for attention tasks. Developmental models have identified adolescence as a vulnerable period for reward-related decision-making due to the development of reward functioning outpacing the maturation of executive function.43 Such a model predicts that adolescents ought to show a greater adverse effect of obesity on reward-related decision-making, which requires the interaction of executive and reward functioning. Contrary to this prediction, the effect of obesity on reward-related decision-making was not significantly moderated by sample age. Perhaps the dissociable effects of sample age on executive and reward-related function relate to differences in the sensitivity of measures or lack of controls for cognitive load or difficulty. They may also reflect a true dissociation in the effect of obesity on executive and reward processes, a ripe area for examination with experimental studies in the future. Nevertheless, it is notable that prevalence of severe obesity (BMI 120% above the 95th percentile) increases from 1.7% in young children to 8.7% in adolescence2 and is associated with increased likelihood of experiencing multiple medical complications44 and decreased quality of life relative to overweight and obese peers.45 Disproportionately more severely obese children in adolescent samples may intensify the negative effect of adiposity, and therefore, adolescence should be more closely examined for identification of cognitive dysfunction and possible intervention efforts.

Gender moderated effects of obesity such that inhibitory deficits were larger in samples with a greater percentage of females. Although rates of pediatric obesity do not differ by gender,2 worse quality of life due to health comorbidities and depression is seen at higher rates in females than males with obesity.46,47 These differences may result in worse response inhibition for girls with obesity as depression can lead to worse executive functioning,48 however, one would also expect that higher rates of depression in females would also negatively affect reward functioning. In adults and adolescents, neural engagement during response inhibition has been seen to differ by gender with greater engagement of frontal-striatal regions in females and greater activation in parietal and motor regions in males.49 Thus, it is possible that those brain-based gender differences underlie the observed moderation of the effect of obesity on response inhibition by gender. Thus, females should be targeted for early intervention and prevention efforts.

Caution is warranted in interpreting the present findings in light of two observations: first, there are sources of heterogeneity that cannot be controlled. Although statistically significant, some models were not robust against potential unpublished or unknown findings (e.g., Working Memory) and prediction intervals indicated substantial heterogeneity in the distribution of true effects ranging from moderate–large negative effects to small positive effects (e.g., Interference, Reward-Related Decision-Making, and Working Memory). Furthermore, cognitive load/task difficulty is an important source of heterogeneity for executive function. For example, cognitive load differs by the proportion of congruent to incongruent trials on Interference tasks and by the requirement to dynamically update what is maintained in working memory.50–52 Such features of study design could not be controlled because they were either not reported or manipulated in few studies.

Second, sociodemographic, study design, and experimental assessment moderators failed to explain heterogeneity for most component processes (except inhibition and attention), which may be due to measurement limitations. Greater adiposity was associated with lower IQ and SES, which is consistent with previous reviews,24 however, they did not moderate association with obesity for executive and reward functioning. The large prediction intervals for these variables indicate substantial heterogeneity in the size of the true effect. Although assessment of IQ is standardized, the construct of SES is not and was assessed differently across studies, potentially contributing to the observed heterogeneity. Only a relatively small proportion of studies reported IQ or SES data, which also may have resulted in reduced power to identify moderation. Furthermore, the failure of included moderators to explain variability across studies highlights a need to include more fine-grained measurement of demographic variables (e.g., race and ethnicity) in future studies so that possible correlates of both obesity and executive functioning can be identified.

In sum, the present results provide a comprehensive view of the status of executive and reward-related functioning in pediatric obesity, which should motivate future experimental work. In addition, we identified potential moderators that should be further examined in prospective studies, to target intervention and prevention efforts. Whether the observed impairment is a cause or consequence of obesity cannot be discerned by the present results. Structural and functional neural differences in the prefrontal cortex, which subserves control processes,12 and in fronto-striatal regions, which subserve reward related decision-making,15 are observed between children with and without obesity, however, whether these differences lead to behaviors that promote obesity or are caused by obesity is yet unknown. Some mechanistic insight is provided by our preliminary findings showing a reversal of behavioral and functional neural differences in frontal-striatal regions following weight-loss surgery,53 suggesting that adiposity has deleterious effects on neural function. Which metabolic factors may drive the observed plasticity remains to be examined in the future.

Supplementary Material

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Denotes papers included in the meta-analysis.

References

- 1.Strauss RS, Pollack HA. Epidemic increase in childhood overweight, 1986–1998. JAMA 2001;286:2845–2848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in Obesity Prevalence Among Children and Adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 Through 2013–2014. JAMA 2016;315:2292–2298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halfon N, Larson K, Slusser W. Associations between obesity and comorbid mental health, developmental, and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample of US Children Aged 10 to 17. Acad Pediatr 2013;13:6–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: Systematic review. Int J Obes 2011;35:891–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinson ML, Vasunilashorn SM. The long-arm of adolescent weight status on later life depressive symptoms. Age Ageing 2016;45:389–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krukowski RA, Smith West D, Philyaw Perez A, et al. Overweight children, weight-based teasing and academic performance. Int J Pediatr Obes 2009;4:274–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinert KRS, Po'e EK, Barkin SL. The relationship between executive function and obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. J Obes 2013;2013:820956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bisset S, Fournier M, Janosz M, Pagani L. Predicting academic and cognitive outcomes from weight status trajectories during childhood. Int J Obes 2013;37:154–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carnell S, Gibson C, Benson L, et al. Neuroimaging and obesity: Current knowledge and future directions. Obes Rev 2011;13:43–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raman J, Smith E, Hay PJ. The clinical obesity maintenance model: An integration of psychological constructs including disordered overeating, mood, emotional regulation, habitual cluster behaviors, health literacy and cognitive function. J Obes 2013;2013:240128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinbeis N, Crone EA. The link between cognitive control and decision-making across child and adolescent development. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2016;10:28–32 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol 2013;64:135–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, et al. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol 2000;41:49–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berridge KC, Robinson TE. Parsing reward. Trends Neurosci 2003;26:507–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horstmann A. It wasn't me; it was my brain—Obesity-associated characteristics of brain circuits governing decision-making. Physiol Behav 2017;176:125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall PA, Fong GT, Epp LJ, Elias LJ. Executive function moderates the intention-behavior link for physical activity and dietary behavior. Psychol Health 2008;23:309–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riggs NR, Chou C-P, Spruijt-Metz D, Pentz MA. Executive cognitive function as a correlate and predictor of child food intake and physical activity. Child Neuropsychol 2010;16:279–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *18.Duckworth AL, Tsukayama E, Geier AB. Self-controlled children stay leaner in the transition to adolescence. Appetite 2010;54:304–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groppe K, Elsner B. The influence of hot and cool executive function on the development of eating styles related to overweight in children. Appetite 2015;87:127–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *20.De Decker A, Sioen I, Verbeken S, et al. Associations of reward sensitivity with food consumption, activity pattern, and BMI in children. Appetite 2016;100:189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seeyave DM, Coleman S, Appugliese D, et al. Ability to delay gratification at age 4 years and risk of overweight at age 11 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:303–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graziano PA, Kelleher R, Calkins SD, et al. Predicting weight outcomes in preadolescence: The role of toddlers' self-regulation skills and the temperament dimension of pleasure. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:937–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlam TR, Wilson NL, Shoda Y, et al. Preschoolers' delay of gratification predicts their body mass 30 years later. J Pediatr 2013;162:90–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrewsbury V, Wardle J. Socioeconomic status and adiposity in childhood: A systematic review of cross-sectional studies 1990–2005. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:275–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ardila A, Pineda D, Rosselli M. Correlation between intelligence test scores and executive function measures. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2000;15:31–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman NP, Miyake A, Corley RP, et al. Not all executive functions are related to intelligence. Psychol Sci 2006;17:172–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hackman DA, Farah MJ, Meaney MJ. Socioeconomic status and the brain: Mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010;11:651–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Somerville LH, Casey BJ. Developmental neurobiology of cognitive control and motivational systems. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2010;20:236–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thamotharan S, Lange K, Zale EL, et al. The role of impulsivity in pediatric obesity and weight status: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2013;33:253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacKillop J, Weafer J, Gray JC, et al. The latent structure of impulsivity: Impulsive choice, impulsive action, and impulsive personality traits. Psychol Bull 2016;233:3361–3370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2014. Available at www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- 33.Del Re AC. Compute.Es: Compute Effect Sizes. R package version 0.2-2; 2013. Available at http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/compute.es

- 34.Viechtbauer W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J Statist Software 2010;36:1–48 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alba AC, Alexander PE, Chang J, et al. High statistical heterogeneity is more frequent in meta-analysis of continuous than binary outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;70:129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruecker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I-2 in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borenstein M, Higgins JPT, Hedges LV, Rothstein HR. Basics of meta-analysis: I2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res Synth Methods 2017;8:5–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley RD, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. Br Med J 2011;342:d549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terrin N, Schmid CH, Lau J, Olkin I. Adjusting for publication bias in the presence of heterogeneity. Statist Med 2003;22:2113–2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sterne J, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. Br Med J 2011;343:d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull 1979;86:638–641 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA. The Adolescent Brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1124:111–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelly A, Barlow SE, Rao G, et al. Severe Obesity in Children and Adolescents: Identification, Associated Health Risks, and Treatment Approaches: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013;128:1689–1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeller MH, Inge TH, Modi AC, et al. Severe obesity and comorbid condition impact on the weight-related quality of life of the adolescent patient. J Pediatr 2015;166:651–659.e654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsiros MD, Olds T, Buckley JD, et al. Health-related quality of life in obese children and adolescents. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2009;33:387–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yagnik PJ, McCormick DP, Ahmad N, Schecter AJ. Childhood and adolescent obesity and depression: A systematic literature review. Int Arch Integr Med 2014;1:23–33 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rock PL, Roiser JP, Riedel WJ, Blackwell AD. Cognitive impairment in depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2014;44:2029–2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubia K, Lim L, Ecker C, et al. Effects of age and gender on neural networks of motor response inhibition: From adolescence to mid-adulthood. NeuroImage. 2013;83:690–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *50.Zamzow J, Culnan E, Spiers M, et al. B-37 The Relationship between Body Mass Index and Executive Function from Late Childhood through Adolescence. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2014;29:550 [Google Scholar]

- *51.Alarcon G, Ray S, Nagel BJ. Lower Working Memory Performance in Overweight and Obese Adolescents Is Mediated by White Matter Microstructure. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2016;22:281–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *52.Pearce AL, Mackey E, Nadler EP, Vaidya CJ. Sleep health and psychopathology mediate executive deficits in pediatric obesity. Child Obes 2018;14:189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pearce AL, Mackey E, Cherry JBC, et al. Effect of Adolescent Bariatric Surgery on the Brain and Cognition: A Pilot Study. Obesity 2017;25:1852–1860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *54.Batterink L, Yokum S, Stice E. Body mass correlates inversely with inhibitory control in response to food among adolescent girls: An fMRI study. NeuroImage 2010;52:1696–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *55.Bauer LO, Kaplan RF, Hesselbrock VM. P300 and the stroop effect in overweight minority adolescents. Neuropsychobiology 2010;61:180–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *56.Bauer LO, Manning KJ. Challenges in the detection of working memory and attention decrements among overweight adolescent girls. Neuropsychobiology 2016;73:43–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *57.Blanco-Gómez A, Ferré N, Luque V, et al. Being overweight or obese is associated with inhibition control in children from six to ten years of age. Acta Paediatr 2015;104:619–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *58.Bonato DP, Boland FJ. Delay of gratification in obese children. Addict Behav 1983;8:71–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *59.Bonato DP, Boland FJ. Response inhibition deficits and obesity in children. Int J Eat Disord 1983;2:61–74 [Google Scholar]

- *60.Bourget V, White DR. Performance of overweight and normal-weight girls on delay of gratification tasks. Int J Eat Disord 1984;3:63–71 [Google Scholar]

- *61.Braet C, Claus L, Verbeken S, Van Vlierberghe L. Impulsivity in overweight children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;16:473–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *62.Bruce AS, Black WR, Bruce JM, et al. Ability to delay gratification and BMI in preadolescence. Obesity 2011;19:1101–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *63.Bruce AS, Lepping RJ, Bruce JM, et al. Brain responses to food logos in obese and healthy weight children. J Pediatr 2013;162:759–764.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *64.Buck SM, Hillman CH, Castelli DM. The relation of aerobic fitness to stroop task performance in preadolescent children. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008;40:166–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *65.Cserjési R, Molnár D, Luminet O, Lénárd L. Is there any relationship between obesity and mental flexibility in children? Appetite 2007;49:675–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *66.Delgado-Rico E, Río-Valle JS, González-Jiménez E, et al. BMI predicts emotion-driven impulsivity and cognitive inflexibility in adolescents with excess weight. Obesity 2012;20:1604–1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *67.Delgado-Rico E, Soriano-Mas C, Verdejo-Román J, et al. Decreased insular and increased midbrain activations during decision-making under risk in adolescents with excess weight. Obesity 2013;21:1662–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *68.Evans GW, Fuller-Rowell TE, Doan SN. Childhood cumulative risk and obesity: The mediating role of self-regulatory ability. Pediatrics 2012;129:e68–e73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *69.Fields SA, Sabet M, Peal A, Reynolds B. Relationship between weight status and delay discounting in a sample of adolescent cigarette smokers. Behav Pharmacol 2011;22:266–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *70.Fields SA, Sabet M, Reynolds B. Dimensions of impulsive behavior in obese, overweight, and healthy-weight adolescents. Appetite 2013;70:60–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *71.Groppe K, Elsner B. Executive function and food approach behavior in middle childhood. Front Psychol 2014;5:447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *72.Guerrieri R, Nederkoorn C, Jansen A. The interaction between impulsivity and a varied food environment: Its influence on food intake and overweight. Int J Obes 2007;32:708–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *73.Gunstad J, Spitznagel MB, Paul RH, et al. Body mass index and neuropsychological function in healthy children and adolescents. Appetite 2008;50:246–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *74.Hjorth MF, Sorensen LB, Andersen R, et al. Normal weight children have higher cognitive performance - Independent of physical activity, sleep, and diet. Physiol Behav 2016;165:398–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *75.Hofmann J, Ardelt-Gattinger E, Paulmichl K, et al. Dietary restraint and impulsivity modulate neural responses to food in adolescents with obesity and healthy adolescents. Obesity 2015;23:2183–2189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *76.Huang T, Tarp J, Domazet SL, et al. Associations of adiposity and aerobic fitness with executive function and math performance in danish adolescents. J Pediatr 2015;167:810–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *77.Hughes SO, Power TG, O'Connor TM, Orlet Fisher J. Executive functioning, emotion regulation, eating self-regulation, and weight status in low-income preschool children: How do they relate? Appetite 2015;89:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *78.Johnson WG, Parry W, Drabman RS. Performance of obese and normal size children on a delay of gratification task. Addict Behav 1978;3:205–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *79.Kamijo K, Khan NA, Pontifex MB, et al. The relation of adiposity to cognitive control and scholastic achievement in preadolescent children. Obesity 2012;20:2406–2411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *80.Kamijo K, Pontifex MB, Khan NA, et al. The association of childhood obesity to neuroelectric indices of inhibition. Psychophysiology 2012;49:1361–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *81.Kamijo K, Pontifex MB, Khan NA, et al. The negative association of childhood obesity to cognitive control of action monitoring. Cereb Cortex 2014;24:654–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *82.Kulendran M, Vlaev I, Sugden C, et al. Neuropsychological assessment as a predictor of weight loss in obese adolescents. Int J Obes 2014;38:507–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *83.Levitan RD, Rivera J, Silveira PP, et al. Gender differences in the association between stop-signal reaction times, body mass indices and/or spontaneous food intake in pre-school children: An early model of compromised inhibitory control and obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2015;39:614–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *84.Li Y, Dai Q, Jackson JC, Zhang J. Overweight is associated with decreased cognitive functioning among school-age children and adolescents. Obesity 2008;16:1809–1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *85.Lu Q, Tao F, Hou F, et al. Cortisol reactivity, delay discounting and percent body fat in Chinese urban young adolescents. Appetite 2014;72:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *86.Maayan L, Hoogendoorn C, Sweat V, Convit A. Disinhibited eating in obese adolescents is associated with orbitofrontal volume reductions and executive dysfunction. Obesity 2011;19:1382–1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *87.Mata F, Verdejo-Román J, Soriano-Mas C, Verdejo-García A. Insula tuning towards external eating versus interoceptive input in adolescents with overweight and obesity. Appetite 2015;93:24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *88.Matton A, Goossens L, Braet C, Vervaet M. Punishment and reward sensitivity: Are naturally occurring clusters in these traits related to eating and weight problems in adolescents? Eur Eat Disord Rev 2013;21:184–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *89.Meule A, Hofmann J, Weghuber D, Blechert J. Impulsivity, perceived self-regulatory success in dieting, and body mass in children and adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Appetite 2016;107:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *90.Miller AL, Rosenblum KL, Retzloff LB, Lumeng JC. Observed self-regulation is associated with weight in low-income toddlers. Appetite 2016;105:705–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *91.Mond JM, Stich H, Hay PJ, et al. Associations between obesity and developmental functioning in pre-school children: A population-based study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1068–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *92.Moreno-López L, Soriano-Mas C, Delgado-Rico E, et al. Brain Structural Correlates of Reward Sensitivity and Impulsivity in Adolescents with Normal and Excess Weight. Bruce A, ed. PLoS One 2012;7:e49185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *93.Nederkoorn C, Braet C, Van Eijs Y, et al. Why obese children cannot resist food: The role of impulsivity. Eat Behav 2006;7:315–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *94.Nederkoorn C, Coelho JS, Guerrieri R, et al. Specificity of the failure to inhibit responses in overweight children. Appetite 2012;59:409–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *95.Nederkoorn C, Jansen E, Mulkens S, Jansen A. Impulsivity predicts treatment outcome in obese children. Behav Res Ther 2007;45:1071–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *96.Niemiro GM, Raine LB, Khan NA, et al. Circulating progenitor cells are positively associated with cognitive function among overweight/obese children. Brain Behav Immun 2016;57:47–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *97.Parisi P, Verrotti A, Paolino MC, et al. Cognitive profile, parental education and BMI in children: Reflections on common neuroendrocrinobiological roots. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2010;23:1133–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *98.Pauli-Pott U, Albayrak O, Hebebrand J, Pott W. Does inhibitory control capacity in overweight and obese children and adolescents predict success in a weight-reduction program? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;19:135–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *99.Pontifex MB, Kamijo K, Scudder MR, et al. V. The differential association of adiposity and fitness with cognitive control in preadolecent children. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 2014;79:72–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *100.Ross N, Yau PL, Convit A. Obesity, fitness, and brain integrity in adolescence. Appetite 2015;93:44–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *101.Ross JM, Graziano P, Pacheco-Colon I, et al. Decision-making does not moderate the association between cannabis use and body mass index among adolescent cannabis users. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2016;22:944–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *102.Scholten EWM, Schrijvers CTM, Nederkoorn C, et al. Relationship between Impulsivity, Snack Consumption and Children's Weight. PLoS One 2014;9:e88851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *103.Schwartz DH, Leonard G, Perron M, et al. Visceral fat is associated with lower executive functioning in adolescents. Int J Obes 2013;37:1336–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *104.Sigal JJ, Adler L. Motivational effects of hunger on time estimation and delay of gratification in obese and nonobese boys. J Genet Psychol 1976;128:7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *105.Skoranski AM, Most SB, Lutz-Stehl M, et al. Response monitoring and cognitive control in childhood obesity. Biol Psychol 2013;92:199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *106.Sobhany MS, Rogers CS. External responsiveness to food and non-food cues among obese and non-obese children. Int J Obes 1985;9:99–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *107.van den Berg L, Pieterse K, Malik JA, et al. Association between impulsivity, reward responsiveness and body mass index in children. Int J Obes 2011;35:1301–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *108.Velders FP, De Wit JE, Jansen PW, et al. FTO at rs9939609, food responsiveness, emotional control and symptoms of ADHD in preschool children. PLoS One 2012;7:e49131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *109.Verbeken S, Braet C, Claus L, et al. Childhood obesity and impulsivity: An investigation with performance-based measures. Behav Change 2009;26:153–167 [Google Scholar]

- *110.Verbeken S, Braet C, Lammertyn J, et al. How is reward sensitivity related to bodyweight in children? Appetite 2012;58:478–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *111.Verbeken S, Braet C, Bosmans G, Goossens L. Comparing decision making in average and overweight children and adolescents. Int J Obes 2014;38:547–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *112.Verdejo-García A, Pérez-Expósito M, Schmidt-Río-Valle J, et al. Selective alterations within executive functions in adolescents with excess weight. Obesity 2010;18:1572–1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *113.Verdejo-García A, Verdejo-Román J, Río-Valle JS, et al. Dysfunctional involvement of emotion and reward brain regions on social decision making in excess weight adolescents. Hum Brain Mapp 2014;36:226–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *114.Wirt T, Hundsdörfer V, Schreiber A, et al. Associations between inhibitory control and body weight in German primary school children. Eat Behav 2014;15:9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *115.Wirt T, Schreiber A, Kesztyüs D, Steinacker JM. Early life cognitive abilities and body weight: Cross-sectional study of the association of inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and sustained attention with BMI percentiles in primary school children. J Obes 2015;2015:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *116.Yau PL, Javier DC, Ryan CM, et al. Preliminary evidence for brain complications in obese adolescents with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2010;53:2298–2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.