Introduction

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is one of the leading causes of acute coronary syndromes in young women and the recommended management is conservative, whenever possible. We describe a case of SCAD presenting with cardiac arrest, which required an emergent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Case Report

A 32-year-old female patient without cardiovascular risk factors complained of chest pain and collapsed at home. Her family members immediately started the cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Upon the arrival of the emergency services, the patient was in cardiac arrest, and the first cardiac rhythm was ventricular fibrillation. After an estimated 3 minutes of no flow, 12 minutes of low-flow, and two defibrillations, a return of spontaneous circulation was obtained. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) on site showed a ST segment elevation in V3-4, as well as in D2-3 and aVF. Therefore, the regional ST-elevation myocardial infarction alarm system was activated, and the patient was transferred directly to the cardiac catheterization laboratory of a tertiary hospital. During the transfer, the patient became hemodynamically unstable and required high-dose catecholamines. Therefore, the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) team was alerted. Coronary angiography via the 6 French femoral access showed a subocclusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery with the TIMI 1 flow in the absence of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (Fig. 1, left panel, and Videos 1 and 2). The angiographic images were compatible with the SCAD of the mid-distal LAD. Based on the flow-limiting nature of the lesion, the hemodynamic instability and the clinical presentation with cardiac arrest, and the following discussion within the Heart Team, we proceeded to PCI of the LAD. The left main coronary artery was engaged with an EBU 3.5 catheter (Launcher, Medtronic, Minneapolis MN, USA). To increase the probability of wiring the true lumen, the dissection was crossed with an olive-tipped guidewire (Magnum, Biotronik, Galway, Ireland). Following the wire advancement, there was no flow in the LAD (Fig. 1, right panel). To document the intraluminal position of the wire, we advanced a second wire (Sion Blue guide; Asahi, Aichi, Japan) inserted through a microcatheter (Caravel, Asahi, Aichi, Japan) aside the first wire. After retrieving the second wire, we injected contrast through the microcatheter to confirm the position in the true lumen of the microcatheter (Fig. 2, left panel, and Video 3). The second wire was readvanced through the microcatheter, while the latter, as well as the olive-tipped guidewire, were retrieved. Following angioplasty, the first stent (Resolute Onyx 3.0×48 mm; Medtronic Ireland, Galway, Ireland) was implanted on the middle segment of the LAD. This led to a propagation of the dissection/intramural hematoma, proximally and distally (Video 4). Subsequently, a second and third stent (Resolute Onyx 2.75×18 mm and 3.0×33 mm) were implanted proximally and distally, respectively. The final angiographic result was favorable with the TIMI III flow (Fig. 2, right panel, and Video 5). Periprocedurally, the patient received 250 mg of aspirin with 6000 U of heparin intravenously and 180 mg of ticagrelor via the nasogastric tube. Following reperfusion, catecholamine could be weaned without the need of ECMO. Subsequently, the patient could be extubated in the absence of neurologic deficit. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T peaked at 1791 ng/L (upper limit of normal 14 ng/L) and echocardiography showed a mild to moderate reduction in the left ventricular function (ejection fraction with 45%) and anteroseptal/apical akinesia. Beta-hCG was negative, and vascular work-up showed no vasculopathy, aneurysms, or signs of fibromuscular dysplasia. The patient was discharged home on Day 12. At 6 months, she was asymptomatic, and echocardiography showed a normalization of the left ventricular function.

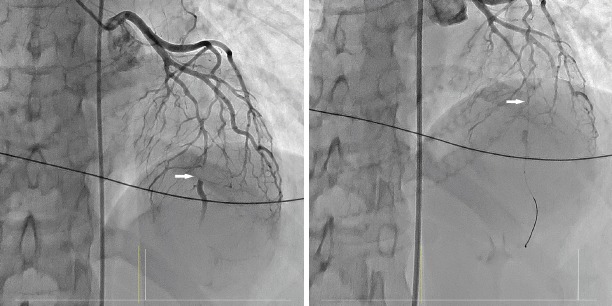

Figure 1.

Coronary angiography in the anterior-posterior cranial view showing subocclusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery with TIMI 1 flow (arrow, left panel). No-reflow after wiring the left anterior descending coronary artery (right panel)

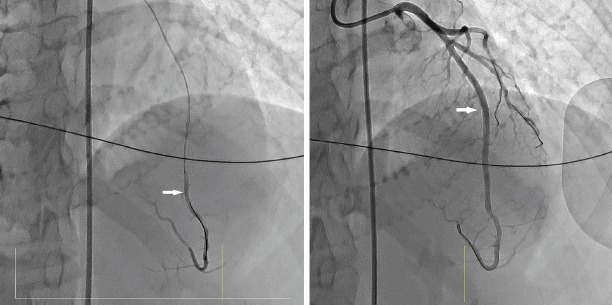

Figure 2.

Injection through the microcatheter to localize the true lumen in the distal segment of the left anterior descending coronary artery (arrow, left panel). The final result of the angioplasty of the left anterior descending coronary artery (right panel)

Discussion

The optimal management of SCAD is challenging, and to the best of our knowledge, no randomized controlled trials are available in the field. A conservative approach is recommended, with the exception of ongoing ischemia involving large coronary territories, hemodynamic instability, or life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias (1,2). Accordingly, PCI may be harmful due to the increased risk of iatrogenic dissection propagation or vessel occlusion (1). If a PCI is required, it is mandatory to ensure the intraluminal position of the wire before angioplasty/stenting. To that purpose, we passed the lesion first with an olive-tipped guidewire, and subsequently, we performed a contrast injection though a microcatheter inserted via a second wire. Not unexpectedly, the stent implantation led to the intramural hematoma propagation proximally and distally, requiring additional stents.

Conclusion

Although conservative therapy is generally recommended in the case of SCAD, PCI may be necessary for ongoing ischemia/life-threatening clinical presentations. The operators should be aware of the technical PCI challenges in this setting.

Video 1

Coronary angiography showed subocclusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery with TIMI 1, compatible with spontaneous coronary artery dissection

Video 2

Right coronary artery angiography without any pathology

Video 3

Injection through microcatheter to localize the true lumen in the distal segment of the left anterior descending coronary artery

Video 4

Angiography showed the prolongation of the dissection proximally and distally in the left anterior descending coronary artery

Video 5

Angiography showed the final result of the angioplasty of the left anterior descending coronary artery

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: M.R. reports institutional research grants from Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Terumo.

Informed consent: The patient was informed and she gave her consent for publishing this case report.

References

- 1.Adlam D, Alfonso F, Maas A, Vrints C Writing Committee. European Society of Cardiology, acute cardiovascular care association, SCAD study group:a position paper on spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3353–68. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saw J, Starovoytov A, Humphries K, Sheth T, So D, Minhas K, et al. Canadian spontaneous coronary artery dissection cohort study:in-hospital and 30-day outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1188–97. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.