Abstract

Aging adults (65+) with disability are especially vulnerable to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and on contracting, they are a cohort most likely to require palliative care. Therefore, it is very important that health services—particularly health services providing palliative care—are proximately available. Treating the Melbourne metropolitan area as a case study, a spatial analysis was conducted to clarify priority areas with a significantly high percentage and number of aging adults (65+) with disability and high barriers to accessing primary health services. Afterward, travel times from priority areas to palliative medicine and hospital services were calculated. The geographic dispersion of areas with people vulnerable to COVID-19 with poor access to palliative care and health services is clarified. Unique methods of health service delivery are required to ensure that vulnerable populations in underserviced metropolitan areas receive prompt and adequate care. The spatial methodology used can be implemented in different contexts to support evidence-based COVID-19 and pandemic palliative care service decisions.

Key Words: COVID-19, palliative care, geographic information system, spatial analysis, disability, health service access

Key Message

A spatial analysis identified priority Melbourne metropolitan areas of aging adults with disability and low access to health services. Priority areas may require unique palliative care offerings in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The methodology can be applied to clarify priority areas of aging adults with disability across different settings.

Introduction

In December 2019, a new coronavirus disease, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), was identified in Wuhan, China.1 By March 26, 2020, more than 450,000 confirmed cases and more than 20,000 deaths across 172 countries had occurred.1 Although diverse age groups can experience the severe consequences of COVID-19, the virus has the most detrimental impact on aging adults older than 65 years.2 Data from the U.S. concludes that more than 31% of adults older than 65 years require hospitalization because of COVID-19, whereas 4%–11% of adults between 65 and 84 years die.2 Furthermore, between 11% and 27% of those older than 85 years die.2

Countries with aging populations such as Australia have reason to be concerned. Currently, 17.7% of people in Australia have a disability, and 15.9% are older than 65 years (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2019).3 The first four cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in Australia on January 26, and the number has quickly increased with 2423 confirmed cases as of March 25.1 The rapidly rising number of people experiencing ill health during a pandemic has the potential to have a detrimental impact on health service delivery, particularly surrounding the provision of palliative care.4 Within countries that have comparable demographics to Australia, it is important that priority areas with significantly high numbers of aging people with disability and poor health service access are identified. Their identification is a seminal first step toward evidence-based health service decisions.

Already, geographic information system methods (hereafter described as spatial methods) have been consistently used toward monitoring and tracking the COVID-19 pandemic.5 Boulos and Geraghty5 detailed how spatial methods have been essential toward the mapping of incidences of COVID-19 globally. They also indicate that spatial methods can be used to support health service decision-making, particularly by supporting the identification of new sites for health services. As an extension of this work, in the absence of resources and time to build new sites for service delivery, such methods can identify where bespoke health service delivery modes—for example, telehealth methods supporting palliative care for aging people with disability—should be delivered.4

As a case study to support future spatial work aimed at addressing service delivery for aging people with disability during a global pandemic, a spatial analysis was conducted to identify priority Melbourne metropolitan areas with a significantly high percentage and number of aging adults (65+) with disability and high barriers to accessing primary health services. Afterward, travel times from priority areas to palliative medicine and hospital services were clarified.

Method

Data Sources

Three sources of data were used. Data from the ABS 2011 Census of Population and Housing6 were used to clarify the number of people 65 years and older who require assistance with a core activity (a proxy for disability). The location of palliative medicine providers and hospital services was identified via Health Direct's 2019 National Health Services Directory,7 and the Metro ARIA8 (an accessibility index for key domains across Australian capital cities) health service index was used to measure access to primary care.

Data Analysis

People older than 65 years were mapped to the Statistical Area 1 level (the second smallest statistical area possible within the Australian geography standard; see ABS9 for more information). To identify areas with significantly high numbers and percentages of aging people with disability, and also poor access to primary health services, three hot spot analyses using the Environmental Systems Reseach Institute's software (Redlands, CA), ArcMap 10.4.1, were conducted. The hot spot (Getis-Ord Gi∗) analysis identifies areas with significantly high and low numbers of a domain given a geospatial mean. Similar to the approach undertaken by Lakhani et al.,10 areas that met the criteria of being significant (at the P < 0.05 level) during all three analyses were identified as priority areas. Afterward, a centroid (a marker representing the center of an area) was produced for each priority area, and the travel time via motor vehicle from priority areas to the nearest palliative medicine and hospital service was clarified via two iterations of the origin destination cost matrix geoprocessing tool. Finally, the travel time was averaged.

Findings

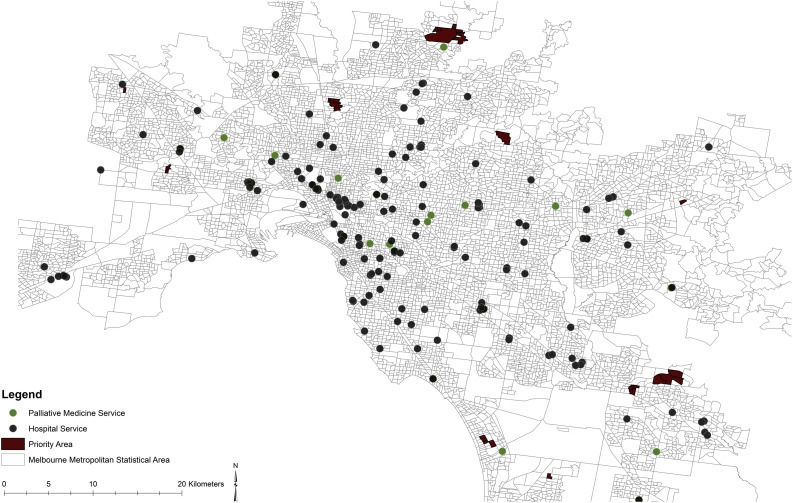

Of 8910 areas, 2085 were identified as having a significantly high level of difficulty accessing primary health services, 807 areas had a significantly high percentage of people with disability, whereas 664 had a significantly high number of people with disability. Thirty areas constituting areas of priority were significant across all three domains. Summary statistics for travel time in minutes to both health services and their averaged travel time are as follows (with mean [M], SD, minimum [min], and maximum [max] in parentheses): palliative care travel time (M = 9.96, SD = 3.46, min = 3.40, and max = 15.45), hospital travel time (M = 9.31, SD = 3.08, min = 2.98, and max = 15.68), average travel time (M = 9.64, SD = 1.37, min = 6.92, and max = 12.22). Fig. 1 clarifies the location of priority areas and palliative medicine and hospital services.

Fig. 1.

Melbourne metropolitan priority areas and palliative medicine and hospital services.

Discussion

Clearly, in light of COVID-19 (or a comparable rapidly spreading virus), unique service offerings are necessary to ensure health support is delivered to those most vulnerable. With Melbourne treated as a case study, priority areas were identified, and the travel time to essential health services was confirmed. The use of such methods can inform global practices for service delivery.

Given the barriers to accessing health services for people in priority areas, an overburdened health system, and the potential for further contamination through contact, service delivery lessons can be learned from offerings of palliative care and related approaches within rural and remote settings where similar barriers exist. The six priorities identified within the Rural Palliative Care Program initiated by Spice et al.11 are relevant. Three of these priorities are particularly suitable given the necessity of isolation: improving psychosocial support for patients and families; providing resources to support home death; and the development and use of a mobile specialist consultant team. Amending service provision with a focus on these priorities can support the delivery of services to vulnerable people within areas with poor access during COVID-19. The first priority listed is especially pertinent as the emergence of COVID-19 could be argued as causal of psychological distress for patients and families.

Essential to providing palliative care services are family caregivers. This is especially so in regions with poor access to health care—once again, for example, rural regions—12 and where health systems are overburdened during a time of pandemic crisis.4 In this regard, telehealth programs that build the skills of family caregivers become paramount.4 Dionne-Odom et al.12 described a telehealth program to support family members of individuals with cancer (hereafter, the program). The program involves six one-hour weekly telehealth sessions for family caregivers to support their provision of palliative care for a family member. In the context of COVID-19, such an approach could be amended so that these sessions are offered at a higher frequency (e.g., daily) and that information surrounding managing relevant COVID-19 symptoms and addressing psychological complications for family members and patients are delivered. Furthermore, including the perspectives of general practitioners with an expertise in palliative medicine for aging people with disability within telehealth sessions would be of benefit. Information sharing around how to manage the distinct consequences of COVID-19 for aging people with disability can ensure a tailored approach where those who may not be able to receive inpatient health services because of service proximity and capacity issues are still able to receive adequate support via informed family members.

Finally, attention needs to be directed to distinct palliative care models that can support the health and well-being of vulnerable populations in priority areas with poor access to health services during a pandemic. Downar and Seccareccia4 provide a palliative care pandemic plan, which includes palliative care considerations that are applicable. Their plan includes the domains: stuff, staff, space, and systems. In relation to the first domain, Donwar and Seccareccia4 highlight the need for adequate stock and delivery of medicine and medical equipment relevant to the particular pandemic. Under the context of COVID-19, an amendment to the stuff component of their plan includes the potential use of unmanned aerial technology—as identified by Boulos and Geraghty5—to deliver medicine and collect samples.

Conclusion

Spatial methods are increasingly becoming an essential method to inform health service planning. However, in the realm of service provision for people with disability and aging people, spatial methods are seldom used.10 The case study provides a spatial method framework that can be followed to identify priority areas for palliative care services in a time of crisis. Irrespective of COVID-19, it is expected that these methods have broader applications in aging societies where palliative care is increasingly becoming used. Coupling spatial methods with contextually appropriate palliative care service offerings is essential toward the delivery of evidence-based effective palliative care.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This research received no specific funding/grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The author declares no conflicts of interest. The data, maps or techniques used in this research draw on EpidorosTM first developed by Griffith University in 2008 in partnership with Metro South Health and Esri Australia with additional funding from the Australian Research Council and the Motor Accident Insurance Commission Qld. Dr. Ali Lakhani would also like to acknowledge Professor Elizabeth Kendall for her continual mentorship and indicating that such work is necessary, and Dr. Ori Gudes and Dr. Peter Grimbeek for their spatial and statistical advice respectively.

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins CSSE coronavirus COVID-19 global cases (dashboard) https://gisan ddata .maps.arcgi s.com/apps/opsda shboa rd/index .html#/bda75 94740 fd402 99423 467b4 8e9ec f6 Available from:

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): older adults. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/specific-groups/high-risk-complications/older-adults.html Available from:

- 3.Australian Bureau of Statistics 4430.0—Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: summary of findings. 2018. www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4430.0 Available from:

- 4.Downar J., Seccareccia D., Associated Medical Services Inc. Educational Fellows in Care at the End of Life Palliating a pandemic: “all patients must be cared for”. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulos M.N., Geraghty E.M. Geographical tracking and mapping of coronavirus disease COVID-19/severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic and associated events around the world: how 21st century GIS technologies are supporting the global fight against outbreaks and epidemics. Int J Health Geogr. 2020;19 doi: 10.1186/s12942-020-00202-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Population Census - Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2011. Census of Population and Housing. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health Direct Australia Ltd . 2019. National Health Services Directory (NHSD) (point) Available from: www.aurin.org.au. Accessed March 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.University of Adelaide—Hugo Centre for Migration and Population Research . 2015. Metro ARIA—Australian capital city urban centres (SA1) Available from: www.aurin.org.au. Accessed March 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Australian Geography Standard: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian statistical geography standard (ASGS): Remoteness structure, 2011.

- 10.Lakhani A., Parekh S., Gudes O. Disability support services in Queensland, Australia: identifying service gaps through spatial analysis. Appl Geogr. 2019;110 102045. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spice R., Paul L.R., Biondo P.D. Development of a rural palliative care program in the calgary zone of alberta health services. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:911–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dionne-Odom J.N., Taylor R., Rocque G. Adapting an early palliative care intervention to family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer in the rural deep south: a qualitative formative evaluation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1519–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]