Coronaviruses are enveloped positive-stranded RNA viruses. Their envelope accommodates three viral membrane proteins. The membrane (M) protein, the subject of this study, is the most abundant envelope protein. The spike (S) protein is involved in binding to the viral receptors and in entry of the virus during the initial stage of infection. The envelope (E) protein is a minor viral component but it is essential for particle assembly. Within the virion envelope a nucleocapsid is present in which the plus-stranded RNA genome is packaged. The M proteins of all coronaviruses are glycosylated. While the group I viruses such as transmissible gastroenteritis virus [TGEV] and the group III viruses (infectious bronchitis virus [IBV]) have M proteins with only N-linked sugars, in the group II viruses (e.g. in mouse hepatitis virus [MHV]) the M protein is invariably O-glycosylated. The MHV M protein, which localizes to the Golgi when expressed alone, is a type III membrane protein (22–25 kDa) with a short (approximately 25 residues) amino-terminal ectodomain and with its carboxy-terminal half located on the inside of virions, which corresponds to the cytoplasmic side of cellular membranes (Rottier, 1995). It contains a cluster of four hydroxylamino acids at its extreme amino terminus, where the O-linked sugars are attached. The oligosaccharides are synthesized by the sequential addition of N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), galactose and sialic acid, followed sometimes by the addition of one or two unidentified sugars (Krijnse Locker et al., 1992). The linkage of the initial GalNAc to the polypeptide in O-glycosylation is carried out by members of the GalNAc-transferase family (Clausen and Bennet, 1996). The maturation of the sugar side chain can be followed easily in biochemical experiments as every sugar gives rise to an electrophoretically detectable shift.

The study presented here focussed on the following questions: (1) How many O-linked side chains are added and to which residue(s)? (2) Does an O-glycosylation sequence motif exist? (3) What is the function of glycosylation and what relevance does the type of glycosylation have for the virus?

1. Identification of the MHV M glycosylation site

In order to identify the residue(s) to which a sugar side chain is added we constructed a number of mutant M proteins, in which either 1 or 2 of the hydroxylamino acids were substituted by alanines (Table 1 ). Wild-type (WT) and mutant M proteins were expressed in OST7-1 cells, pulse-labeled and chased. The appearance of electrophoretically slower migrating M protein species during the chase indicates the addition of O-linked sugars. Since none of the single substitutions of the hydroxylamino acids abolished O-glycosylation, multiple or alternative acceptor sites apparently exist. Only the mutant in which both threonines were substituted remained unmodified. We next prepared an additional set of M proteins with mutations in the cluster of hydroxylamino acids leaving only one threonine residue (Table 1). It appeared that the M protein could be modified at both its threonines, indicating the presence of alternative acceptor sites. Since the threonine at position 5 was glycosylated more efficiently than threonine at position 4, threonine 5 is the most likely candidate acceptor residue for O-glycosylation in WT M. Mutant M proteins with only one acceptor site made a similar shift in electrophoretic mobility as WT M, indicating that in WT M only one residue at a time is modified by O-linked sugars.

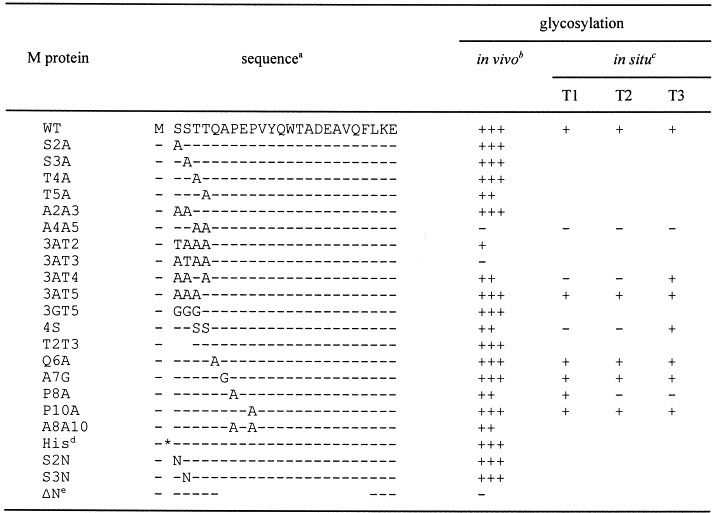

Table 1.

Mutant M proteins and their O-glycosylation

|

aAmino acid sequence of the M protein ectodomains. Hyphens indicate residues identical to those of WT M. Gaps are introduced for maximal alignment. bComparative semi-quantitative analysis of the glycosylation of the expressed M proteins: +++, ++ and + indicate efficient, less efficient and inefficient glycosylation, respectively; − indicates no glycosylation. cGlycosylation of ER-retained M proteins by ER-retained transferases. T1, T2 and T3 represent GalNAc transferase 1, 2 and 3. Whether M proteins are substrates is indicated by + and −. dThe asterisk indicates an insertion of six histidines.

2. In search of an O-glycosylation sequence motif

Assuming that GalNAc transferases recognize a specific sequence motif we investigated the effect of mutations in and around the hydroxylamino acid cluster (Table 1). The results indicate that a cluster of hydroxyl-amino acids per se is not required. Furthermore, the identity of the hydroxyl-amino acid at position 4 or 5 is not essential, since an M protein containing serine residues instead of threonine was still glycosylated. Also the distance with respect to the initiating methionine appeared not to be important. Furthermore, none of the amino acid substitutions downstream of the hydroxylamino acid cluster blocked O-glycosylation of the M protein. However, the presence of the proline 3 residues downstream of the functional acceptor site is beneficial for O-glycosylation. Altogether these results suggest that a specific sequence motif does not occur but that the requirements for O-glycosylation are flexible.

Recently, several different GalNAc transferases have been identified in eukaryotic cells. If we assume that these enzymes each have their own sequence specificities this might explain our inability to reveal a precise sequence motif for O-glycosylation. We therefore decided to study this issue. We used an in situ O-glycosylation assay which allowed us to analyse the primary sequence requirements of three different GalNAc-transferases using MHV M as the substrate. The in situ assay is based on the co-expression of ER-retained forms of the GalNAc-transferases T1, T2, or T3 and of the substrate (Röttger et al., 1998). GalNAc-transferases are normally localized to the Golgi complex. Endogenous GalNAc-transferase activity is not present in the ER, but the enzymes do function when retained (Röttger et al., 1998). A selection of our M protein mutants was provided with the double-lysine ER retention signal and tested in the in situ glycosylation assay (Table 1). The results indicate that the three GalNAc-transferases have largely overlapping, but distinct substrate specificities. They presumably explain why an in vivo O-glycosylation consensus sequence could not be identified. Finally, the results support the hypothesis that O-glycosylation of proteins is determined by the combined activities of all GalNAc-transferases present in particular cells. The differential expression of GalNAc transferases glycosylation in cells or tissues of the organism might thus be a mechanism to modulate the O-glycosylation of proteins.

3. The function of coronavirus M protein glycosylation

The hydroxylamino acid motif and the proline residue at position +3 relative to the most C-terminal threonine of the cluster are very well conserved in the M proteins of group II coronaviruses. Since glycosylation may vary from cell to cell depending on the expressed repertoire of GalNAc-transferases, these conserved features may serve to increase the opportunities for the M proteins to become glycosylated in many different cell types. Similarly, the N-glycosylation motifs in the M proteins of group I and III coronaviruses are also highly conserved.

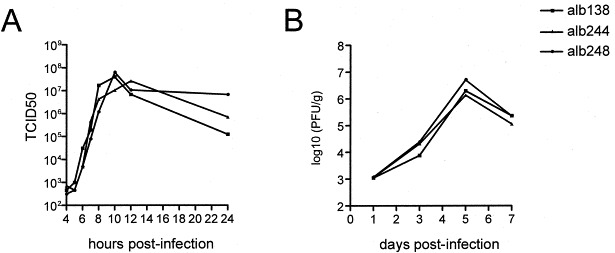

The conservation of the N- and O-glycosylation motifs in the coronavirus M proteins suggests that the presence and the particular type of carbohydrates are beneficial to the virus. Since glycosylation is not required for virus assembly (de Haan et al., 1998) we favor the idea that somehow the carbohydrates are involved in virus–host interaction. To examine the role of glycosylation of the ectodomain of the M protein, mutations expected to either ablate glycosylation or alter the glycosylation type were directly introduced into the genome of MHV by targeted RNA recombination. In this way, recombinant viruses were generated that carried M proteins that were either O-glycosylated (Alb138), N-glycosylated (Alb244), or not glycosylated at all (Alb248). After confirmation of their genotypes and protein phenotypes, the recombinant viruses were analyzed for their in vitro growth properties. The recombinant viruses displayed no obvious differences with respect to plaque size or growth in tissue culture and exhibited similar one-step growth characteristics (Fig. 1 A). Next we determined the virulence of the recombinant viruses using intracranial inoculation of C57Bl/6 mice. All recombinant viruses appeared to have the same LD50 or virulence and they replicated to the same titers in the brain (Fig. 1B). Similar results were obtained when the mice were inoculated intranasally. Apparently, the M protein glycosylation state is not an important virulence factor.

Fig. 1.

Growth of recombinant MHVs in vitro and in vivo. (A) Single-step growth kinetics of Alb138 (O+N−), Alb244 (O−N−), and Alb248 (O+N−) in murine L cells. Viral infectivity in culture medium at different times post-infection was determined by a quantal assay on L cells, and 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) were calculated. (B) Replication of Alb138, Alb 244 and Alb248 in mice. Mice were inoculated intracranially with 1.0×103 PFU of virus. On days 1, 3, 5, and 7 post-infection, mice were sacrificed and virus titers in the brain were determined by plaque-assay. The data shown represent the means of the titers from four animals.

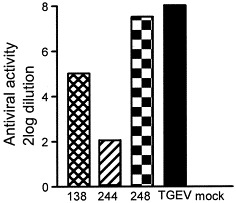

Although the function of M protein glycosylation is still enigmatic, it may correlate with the finding that several coronaviruses including MHV and TGEV were able to induce alpha interferon (IFNα). Type I interferons (including IFNα) are an important component of the first line of defense against virus infections. For TGEV, the oligosaccharides N-linked to the M protein were demonstrated earlier to be important for efficient IFNα induction (Laude et al., 1992). Mutations in the M protein ectodomain that impaired N-glycosylation decreased the interferogenic activity. In view of these results we tested the interferogenic capacity of our recombinant MHVs (Fig. 2 ). Coronaviruses containing M proteins with N-linked sugars appeared to induce type I IFN to higher levels than viruses carrying M proteins with O-linked sugars. MHV with unglycosylated M proteins appeared to be a poor IFN inducer.

Fig. 2.

Induction of alpha interferon. LMR cells were infected with Alb138 (O+N−), Alb244 (O−N−), Alb248 (O−N+), or TGEV (O−N+) at a multiplicity of 10 PFU per cell. At 91/2 h post-infection cells were fixed o/n with 3% formaldehyde. Porcine peripheral blood mononuclear (PBM) cells were induced to produce IFNα by overnight incubation on the TGEV- or MHV-infected fixed cells. Supernatants were collected and serial log2 dilutions of supernatants from induced PBM cells were assayed for IFN activity on LMR cells using vesicular stomatitis virus as a challenge. The IFN produced by the porcine PBM cells was characterized as mainly consisting of IFNα because it was neutralized for over 90% by an anti-IFNα serum (Laude et al., 1992).

In summary, the structural requirements for O-glycosylation of the MHV M protein have been characterized. No unique sequence motif for O-glycosylation could be identified, which is conceivably due to the presence of multiple GalNAc-transferases. Indeed, MHV M served as a substrate for three GalNAc-transferases in an in situ glycosylation assay. Recombinant viruses were generated that carried M proteins that were either O-glycosylated, N-glycosylated, or not glycosylated at all. The M protein glycosylation state appeared not to influence the tissue culture growth characteristics of recombinant viruses. Also no differences could be detected in the virulence and the in vivo growth characteristics of the recombinant viruses. However, MHV containing M proteins with N-linked sugars displayed a significantly higher interferogenic capacity than virus carrying O-glycosylated M proteins, while MHV with unglycosylated M proteins appeared to be a poor IFN inducer.

The studies presented here give new insights into questions related to O-glycosylation in general and to the glycosylation of the coronavirus M protein in particular. However, some important issues still remain. Most intriguing is the question why the different coronaviruses have so strictly conserved the particular glycosylation of their M protein and for what biological reason. Our results suggest that it has to do with the modulation of an antiviral immune response. However, the advantage of such responses for the viruses remains enigmatic.

References

- Clausen H., Bennet E.P. A family of UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases control the initiation of mucin-type O-linked glycosylation. Glycobiology. 1996;6:635–646. doi: 10.1093/glycob/6.6.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan C.A.M., Kuo L., Masters P.S., Vennema H., Rottier P.J.M. Coronavirus particle assembly: primary structure requirements of the membrane protein. J. Virol. 1998;72:6838–6850. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6838-6850.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijnse Locker J., Griffiths G., Horzinek M.C., Rottier P.J.M. O-glycosylation of the coronavirus M protein. Differential localization of the sialyltransferases in N- and O-linked glycosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:14 094–14 101. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)49683-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laude H., Gelfi J., Lavenant L., Charley B. Single amino acid changes in the viral glycoprotein M affect induction of alpha interferon by the coronavirus transmissible gastroenteritis virus. J. Virol. 1992;66:743–749. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.743-749.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottier P.J.M. The coronavirus membrane protein. In: Siddell S.G., editor. The Coronaviridae. Plenum Press; New York: 1995. pp. 115–139. [Google Scholar]

- Röttger S., White J., Wandall H., Olivo J.C., Stark A., Bennet E., Whitehouse C., Berger E., Clausen H., Nilsson T. Localization of three human polypeptide GalNAc-transferases in HeLa cells suggests initiation of O-linked glycosylation throughout the Golgi apparatus. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:45–60. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]