Abstract

Cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are escalating rapidly across the globe, with the mortality risk being especially high among those with existing illness and multimorbidity. This study aimed to synthesize evidence for the role and response of palliative care and hospice teams to viral epidemics/pandemics and inform the COVID-19 pandemic response. We conducted a rapid systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines in five databases. Of 3094 articles identified, 10 were included in this narrative synthesis. Included studies were from West Africa, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, the U.S., and Italy. All had an observational design. Findings were synthesized using a previously proposed framework according to systems (policies, training and protocols, communication and coordination, and data), staff (deployment, skill mix, and resilience), space (community provision and use of technology), and stuff (medicines and equipment as well as personal protective equipment). We conclude that hospice and palliative services have an essential role in the response to COVID-19 by responding rapidly and flexibly; ensuring protocols for symptom management are available, and training nonspecialists in their use; being involved in triage; considering shifting resources into the community; considering redeploying volunteers to provide psychosocial and bereavement care; facilitating camaraderie among staff and adopting measures to deal with stress; using technology to communicate with patients and carers; and adopting standardized data collection systems to inform operational changes and improve care.

Key Words: COVID-19, coronavirus, pandemic, palliative care, hospice, end of life

Key Message

An evidence synthesis on the role and response of hospice and palliative care in epidemics/pandemics to inform response to coronavirus disease 2019. Hospice and palliative care services should respond rapidly and flexibly, produce protocols, shift resources to the community, redeploy volunteers, facilitate staff camaraderie, communicate with patients/carers via technology, and standardize data collection.

Introduction

The relief of suffering, supporting complex decision making, and managing clinical uncertainty are key attributes of palliative care and essential components of the response to epidemics and pandemics.1 The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is escalating rapidly across the globe. Those affected experience symptoms including breathlessness, cough, myalgia, and fever. The mortality risk is especially high among those with existing illness and multimorbidity.

Pandemics such as that caused by COVID-19 can lead to a surge in demand for health care services, including palliative and end-of-life care.2 These services must respond rapidly, adopting new ways of working as resources are suddenly stretched beyond their normal bounds. Globally, palliative care is now seen as an essential part of universal health coverage. To inform the palliative care response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we aimed to rapidly synthesize evidence on the role and response of palliative care and hospice services to viral epidemics/pandemics.

Methods

Design

Rapid systematic review according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

-

•

Population—patients, carers, health care professionals, other experts, wards, units, and services

-

•

Intervention—palliative care, hospice care, end-of-life care, and supportive care

-

•

Context—viral epidemics or pandemics characterized by rapid transmission through the population and requiring a rapid response from the health system, including Ebola, severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome, avian influenza, and COVID-19. HIV was excluded because of its slower transmission through the population.

-

•

Findings—role and/or response of palliative care and hospice services

-

•

Study design—case studies, cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, and intervention studies (opinion pieces and editorials excluded)

-

•

Language—no limits

Search Strategy

We searched five databases (MEDLINE [1966–2019], Embase [1980–2019], PsycINFO [1967–2019], CINAHL [1982–2019], and Web of Science [1970–2019]). The search strategy comprised terms for palliative care, hospice care, and end-of-life care as well as terms for pandemics and epidemics including specific named pandemics (Appendix). We identified and screened the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews, government and nongovernmental organization reports, opinion pieces, and included articles.

Study Selection

One researcher (S. N. E.) completed all searches and removed duplicate records. Articles were screened in EndNote (version X9, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA) using titles and abstracts by R. L. C., K. E. S., and S. N. E. Full texts were screened by K. E. S. and N. L.

Data Extraction

A bespoke data extraction form was created in Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Data were extracted by two researchers (K. E. S. and N. L.) and checked by a third researcher (A. E. B.). We did not appraise the quality of included studies.

Analysis

We conducted narrative synthesis and used the framework proposed by Downar and Seccareccia2 to group recommendations. This framework, based on an established model of intensive care surge capacity, suggests that a palliative pandemic plan should include focus on systems, space, staff, and stuff.2

Results

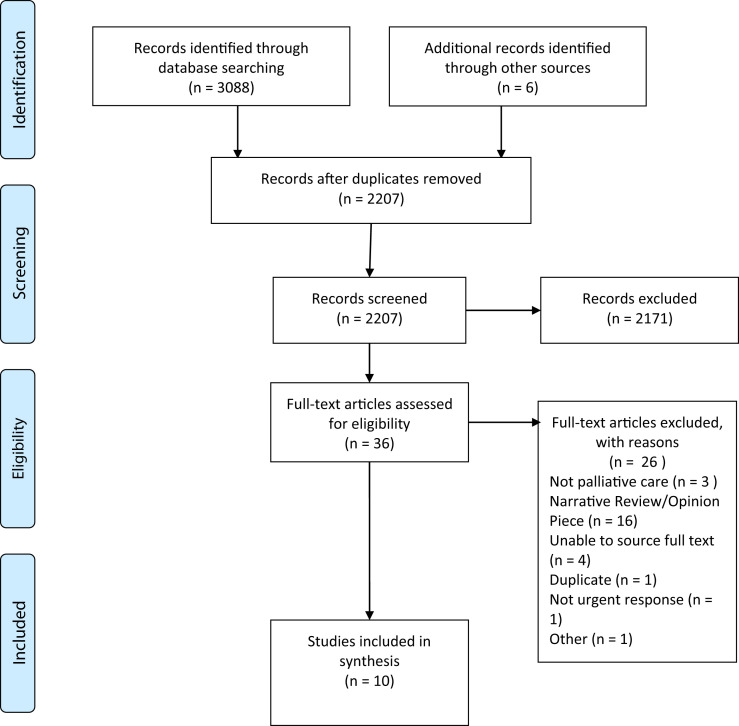

We identified 3088 articles from database searches (search date: March 18, 2020) and identified six additional articles through screening the reference lists of relevant articles and reports. After removing duplicates, 2207 articles remained. Thirty six articles underwent full-text review, and 10 articles were included in the analysis (Fig. 1 ; Table 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart.

Table 1.

Description of Included Studies

| Authors, yr | Context | Study Aim | Study Design | Setting/Participants | Findings and Author Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costantini et al., 20205 | Italy, coronavirus (COVID-19) | To examine the preparedness for and impact of COVID-19 on hospices in Italy to help inform the responses of other countries | Cross-sectional telephone survey | 16 hospices | Hospice response to COVID-19:

|

| Battista et al., 20196 | West Africa, EVD | To identify care measures and barriers and facilitators to their implementation for patients with EVD | Cross-sectional online survey | 29 clinicians and decision makers (24 physicians, three nurses, and two involved in project management and coordination) | Barriers to the provision of supportive care:

|

| Loignon et al., 20187 | West Africa, EVD | To document barriers to supportive care in Ebola treatment units | Qualitative telephone interviews | 29 clinicians and decision makers, comprising 25 physicians, three nurses, and one other | Barriers to the provision of supportive care:

|

| Dhillon et al., 20158 | West Africa, EVD | To describe the treatment course of a man admitted to an Ebola treatment center and to describe some of the challenges identified | Case report | One 33-yr-old man admitted to an Ebola treatment center who died from Ebola-related complications 18 days later | Challenges identified in providing care for an Ebola patient:

|

| Michaels-Strasser et al., 20159 | Sierra Leone, EVD | To assess the outcome or effectiveness of community care centers for rapid isolation and palliative care of people with suspected Ebola disease | Cross-sectional assessment using direct observation, a site assessment survey, and staff interviews | 11 community care centers and 58 key informants | Description and assessment of community care centers:

|

| Cheng et al., 201410 | Hong Kong, avian influenza | To explain measures taken by palliative care services in Hong Kong during the H7N9 influenza | Case study of a service | The first confirmed case of human avian influenza A (H7N9) | Response to avian influenza within a palliative care unit:

|

| Matzo et al., 20093 | Hypothetical mass casualty event from an influenza pandemic or other event | To understand the role of palliative care in mass casualty events and to make recommendations | Qualitative telephone interviews and group meeting with experts | 10 disaster management and public health experts | Issues for palliative care in mass casualty event:

|

| Cinti et al., 20084 | U.S., simulation exercise | To describe learning after simulation exercises for pandemic events | Simulation exercises with recommendations | A large tertiary care center with 913 beds | An ACC was described as four pods accommodating a total of 250 patients, providing limited supportive care for noncritical pandemic influenza patients and some who would require palliative care Authors concluded that: more attention was needed on palliative care and fatality management; plans should include involvement of clergy; palliative care protocols are essential, and there should be training for site leads in their use; and palliation medications should be included on the formulary |

| Chen et al., 200612 | Taiwan, SARS | To describe changes in hospice inpatient utilization during and after the SARS epidemic in 2003 in Taiwan | Retrospective study using administrative data | Hospice wards within 15 hospitals | Changes in hospice inpatient utilization during SARS epidemic: During the peak SARS period, the number of admissions to the 15 hospice wards decreased to 69% of those in the previous year, and inpatient day units reduced to 54%. It was not known whether the decrease in utilization was due to patients' voluntary decisions or hospital policies, and the study could not determine whether the needs of patients with terminal illnesses were met during the epidemic The authors concluded that the ability to shift resources from inpatient to community settings would improve care and that seamless continuity of care between facilities and settings should be ensured at all times |

| Leong et al., 200411 | Singapore, SARS | To describe the psychosocial impact of providing holistic care in an epidemic | Qualitative interviews | Eight health care professionals (doctors, nurses, social workers, and pharmacists) in a palliative care unit | Psychosocial impact of providing holistic care in an epidemic:

|

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; PPE = personal protective equipment; EVD = Ebola virus disease; ACC = alternative care center; SARS = severe acute respiratory syndrome.

The 10 articles were published between 2004 and 2020. Two articles concerned planning for pandemics,3 , 4 seven articles described data collected during epidemics/pandemics,5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and one article studied an epidemic retrospectively.12

The settings included West Africa,6, 7, 8, 9 Taiwan,12 Hong Kong,10 Singapore,11 the U.S.,4 and Italy.5 One article had no defined setting.3 Eight of the articles concerned specific epidemics/pandemics (including Ebola,6, 7, 8, 9 severe acute respiratory syndrome,11 , 12 influenza,3 , 10 and one on COVID-193).

We synthesized findings according to Downar and Seccareccia model of systems, staff, space, and stuff (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Synthesis of Evidence and Recommendations for the Palliative Care Response to COVID-19

| Systems |

|

| Staff |

|

| Space |

|

| Stuff |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; PPE = personal protective equipment.

Discussion

We provide the first evidence synthesis to guide hospice and palliative care teams in their response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Key findings were the need for teams to be flexible and rapidly redeploy resources in the face of changing need. For hospital teams, this involves putting in place protocols for symptom control and training nonspecialists in their use. Hospice services may see a shift in need and should be prepared to focus their resources on community provision.

This was a rapid review, and we did not assess quality of studies or grade our recommendations. We found existing evidence to be limited. All identified studies were observational, quantitative data were rare, and there were no studies with an experimental design. Most studies were from Asia or Africa, with one study from Europe, and one from the U.S. This reflects the fact that Europe and the U.S. are less experienced at responding to pandemics than other regions, and this may in turn result in a lack of preparedness to respond to COVID-19. Although the importance of palliative care in response to pandemics has been well documented,1 , 13 this is not reflected in pandemic plans or in palliative care training, and the research literature is sparse.

There were gaps in evidence, particularly around the role of palliative care teams in acute hospitals. There was also relatively little data on provision of palliative care in community settings, although in two studies, a reduction in demand for inpatient care was seen and led to the suggestion to shift resources into the community.5 , 12 Community palliative care can facilitate advance care planning and symptom control and helps prevent hospital admissions among people near the end of life.14 It is likely that community palliative care may help prevent hospital admissions among people dying from COVID-19 who would prefer to remain at home or in their care home, although this has not been tested. However, the rapid escalation of breathlessness in patients with COVID-19 who develop acute respiratory distress syndrome may make this challenging.15 Severe breathlessness and respiratory disease are both known to be associated with increased hospital admissions at the end of life.16 Therefore, rapid community response may be needed to manage advanced disease in COVID-19 if people are to remain at home.

Two studies reported cessation of hospice volunteer services in response to pandemics.5 , 10 An alternative role for volunteers may be in provision of psychological support for patients and carers, which could occur by using digital technology or telephones. In light of the social distancing measures being widely used in response to COVID-19, volunteers may have a wider role in supporting communities, for example, helping the most vulnerable with shopping for food and medicines.

Providing palliative care in pandemics can be compromised by the hostile environment, infection control mechanisms, and extreme pressure on services.10 In addition, the family unit of care may be disrupted. Even so, provision of palliative care is an ethical imperative for those unlikely to survive and may have the advantage of diverting dying people away from overburdened hospitals as well as providing the care that people want.3 Pandemic situations introduce complex ethical challenges concerning allocation of scarce resources, and palliative care teams are well placed to help patients and carers discuss preferences and make advance care plans.

Data collection systems to understand outcomes and share learning are important in a palliative pandemic response. However, these are frequently lacking.9 Such data should ideally include numbers of patients seen, as well as their main symptoms and concerns, treatments, effectiveness of treatment and outcomes. There is also a need to understand the prevalence of palliative care needs that are not met by palliative and hospice services. In a pandemic expected to last for several months such as COVID-19, implementing systems of data collection early would help services to plan for and improve care and could be used to project future needs.

Conclusion

Providing holistic care in a pandemic can be compromised by extreme pressure on services. Hospice and palliative care services can mitigate against this by maintaining the ability to respond rapidly and flexibly; ensuring protocols for symptom management and psychological support are available, and nonspecialists are trained in their use; being involved in triage; considering shifting resources from inpatient to community settings; considering redeploying volunteers to provide psychosocial and bereavement care; facilitating camaraderie among staff and adopting measures to deal with stress; use of technology to communicate with patients and carers; and adopting standardized data collection systems to inform operational changes and improve care. Long-term priorities should include ensuring palliative and hospice care are integrated into pandemic plans.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This research received no specific funding/grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. K. E. S. is funded by a UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) clinician scientist fellowship (CS-2015-15-005); I. J. H. is an NIHR senior investigator emeritus and is supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration South London at King's College Hospital National Health Service Foundation Trust. I. J. H. leads the Palliative and End of Life Care theme of the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration South London and coleads the national theme in this. R. L. C. is funded by Marie Curie and Cicely Saunders International; A. E. B. is funded by Cicely Saunders International and the Dunhill Medical Trust. S. N. E., N. L., and A. E. B. are previous Cicely Saunders International PhD training fellows. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, or the funding charities. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.029.

Supplementary Data

COVID PRISMA 2009 Checklist

Supplementary Material

Appendix

Appendix. Search Strategy

There were no restrictions for language or publication date. Searches were completed on March 18, 2020.

MEDLINE and Embase

(palliative care/OR palliative medicine/OR palliate$.mp. OR hospices/OR terminally ill/OR terminal care/OR hospice$.mp. OR end of life.mp. OR EOL.mp.) AND (exp pandemics/OR pandemic$.mp. OR epidemic$.mp. OR epidemics/OR exp disease outbreaks/OR disease outbreaks.mp. OR SARS.mp. OR SARS virus/OR Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome/OR coronavirus/OR coronavirus.mp. OR exp coronavirus infections/OR ebolavirus/OR influenza, human/OR influenza.mp. OR hemorrhagic fever, ebola/OR mers.mp. OR flu.mp. OR Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus/OR Tuberculosis/OR Pulmonary tuberculosis/OR Tuberculosis, multi-drug resistant/OR Extensively drug resistant tuberculosis/OR TB.mp.)

PsycINFO

(palliative care/OR palliate$.mp. OR hospice/OR terminally ill patient/OR terminal care.mp. OR hospice$.mp. OR end of life.mp. OR EOL.mp.) AND (exp pandemics/OR pandemic$.mp. OR epidemic$.mp. OR exp epidemics/OR disease outbreaks.mp. OR SARS.mp. OR Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome.mp. OR coronavirus.mp. OR influenza/OR swine influenza OR ebola.mp. OR ebolavirus.mp. OR influenza.mp. OR mers.mp. OR flu.mp. OR Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus.mp. OR Tuberculosis/OR Pulmonary tuberculosis/OR multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.mp. OR extensively drug resistant tuberculosis.mp. OR TB.mp.)

CINAHL

Searched for the below as title, abstract, and keywords.

(Palliative care OR palliative medicine OR palliat∗ OR hospice∗ OR terminally ill OR terminal care OR end of life OR eol) AND (pandemic∗ OR epidemic∗ OR disease outbreak OR SARS OR Severe acute respiratory syndrome OR SARS virus OR coronavirus OR coronavirus infections OR influenza OR flu OR MERS OR middle east respiratory syndrome OR ebola virus OR ebola OR Tuberculosis OR multidrug-resistant tuberculosis)

Web of Science

TS=((palliative care OR palliative medicine OR palliat∗ OR hospice∗ OR terminally ill OR terminal care OR eol) AND (pandemic∗ OR epidemic∗ OR disease outbreak OR SARS OR Severe acute respiratory syndrome OR SARS virus OR coronavirus OR coronavirus infections OR influenza OR flu OR MERS OR middle east respiratory syndrome OR ebola virus OR ebola OR Tuberculosis OR multidrug-resistant tuberculosis))

References

- 1.Powell R.A., Schwartz L., Nouvet E. Palliative care in humanitarian crisis: always something to offer. Lancet. 2017;389:1498–1499. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30978-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Downar J., Seccareccia D. Palliating a pandemic: “all patients must be cared for”. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matzo M., Wilkinson A., Lynn J., Gatto M., Phillips S. Palliative care considerations in mass casualty events with scarce resources. Biosecur Bioterror. 2009;7:199–210. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2009.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cinti S.K., Wilkerson W., Holmes J.G. Pandemic influenza and acute care centres: taking care of sick patients in a nonhospital setting. Biosecur Bioterror. 2008;6:335–348. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2008.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costantini M., Sleeman K.E., Peruselli C., Higginson I.J. Response and role of palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national telephone survey of hospices in Italy. Palliat Med. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0269216320920780. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Battista M.C., Loignon C., Benhadi L. Priorities, barriers, and facilitators towards international guidelines for the delivery of supportive clinical care during an ebola outbreak: a cross-sectional survey. Viruses. 2019;11:194. doi: 10.3390/v11020194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loignon C., Nouvet E., Couturier F. Barriers to supportive care during the Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa: results of a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhillon P., McCarthy S., Gibbs M., Sue K. Palliative care conundrums in an Ebola treatment centre. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-211384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michaels-Strasser S., Rabkin M., Lahuerta M. Innovation to confront Ebola in Sierra Leone: the community-care-centre model. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e361–e362. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng H.W., Li C.W., Chan K.Y., Sham M.K. The first confirmed case of human avian influenza A(H7N9) in Hong Kong and the suspension of volunteer services: impact on palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:e5–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.12.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leong I.Y., Lee A.O., Ng T.W. The challenge of providing holistic care in a viral epidemic: opportunities for palliative care. Palliat Med. 2004;18:12–18. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm859oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen T., Lin M., Chou L., Hwang S. Hospice utilization during the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:94. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosoff P.M. A central role for palliative care in an influenza pandemic. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1051–1053. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomes B., Calanzani N., Curiale V., McCrone P., Higginson I.J. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD007760. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007760.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bone A.E., Gao W., Gomes B. Factors associated with transition from community settings to hospital as place of death for adults aged 75 and older: a population-based mortality follow-back survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:2210–2217. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

COVID PRISMA 2009 Checklist

Supplementary Material