Abstract

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the major causes of chronic liver disease worldwide. Currently, no successful treatments are available for ALD. The pathogenesis of ALD is characterized as simple steatosis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis (AH), and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Autophagy is a highly conserved intracellular catabolic process, which aims at recycling cellular components and removing damaged organelles in response to starvation and stresses. Therefore, autophagy is considered as an important cellular adaptive and survival mechanism under various pathophysiological conditions. Recent studies from our lab and others suggest that chronic alcohol consumption may impair autophagy and contribute to the pathogenesis of ALD. In this chapter, we summarize recent progress on the role and mechanisms of autophagy in the development of ALD. Understanding the roles of autophagy in ALD may offer novel therapeutic avenues against ALD by targeting these pathways.

1. Introduction

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is a major health problem and a significant source of chronic liver injury worldwide. In 2012, about 3.3 million deaths, or 5.9% of all global deaths, were attributed to alcohol consumption (WHO). The latest surveillance report published by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) showed that liver cirrhosis was the 12th leading cause of death in the United States, with a total of 42,443 deaths in 2015, 49.5% of which were estimated to be attributed to ALD (Yoon, 2018). ALD comprises a spectrum of disorders and pathologic changes in individuals with acute and chronic alcohol consumption, ranging from alcoholic steatosis to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis (AH) and liver cancer (Gao & Bataller, 2011; Nagy, Ding, Cresci, Saikia, & Shah, 2016; Williams, Manley, & Ding, 2014).

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is an evolutionarily conserved and programmed intracellular degradation pathway in response to starvation and stresses. It is involved in the trafficking of long-lived proteins and cellular organelles via the formation of autophagosomes, which then fuse with lysosomes for degradation to maintain cellular homeostasis. Autophagy is generally considered as a pro-survival mechanism in response to various stress conditions and plays a critical role in normal liver physiology and liver diseases (Czaja et al., 2013; Ding, 2010; Yin, Ding, & Gao, 2008).

Accumulating evidence has shown that altered autophagy is implicated in the pathogenesis and protection of alcohol-induced tissue injury (Czaja et al., 2013; Ding, Li, & Yin, 2011; Ding, Manley, & Ni, 2011; Dolganiuc, Thomes, Ding, Lemasters, & Donohue, 2012; Li, Wang, Ni, Huang, & Ding, 2014). In this chapter, we summarize recent findings about the roles and the underlying molecular mechanisms of autophagy in the development of ALD.

2. Alcohol metabolism

Metabolism of alcohol has been extensively studied (Cederbaum, 2012; Zakhari, 2006; Zelner, Matlow, Natekar, & Koren, 2013). Briefly, it is metabolized mainly in the liver and through both major oxidative and minor non-oxidative pathways. The most common oxidative pathway of alcohol metabolism in the liver is catalyzed by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), which converts alcohol into highly reactive metabolite, acetaldehyde (Crabb, Matsumoto, Chang, & You, 2004). Alcohol can also be oxidized into acetaldehyde by cytochrome P450 family 2, subfamily E, polypeptide 1 (Cyp2E1) and catalase (Crabb et al., 2004; Lu & Cederbaum, 2008). The highly reactive acetaldehyde forms adducts with other macromolecules, such as proteins, leading to alteration of protein functions, loss of activity and subsequent liver injury (Setshedi, Wands, & Monte, 2010). Acetaldehyde is further metabolized by mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) into more harmless acetate and acetyl-CoA for use in metabolic pathways (Crabb et al., 2004). The metabolism of alcohol through this pathway increases the conversion of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) into its reduced form, NADH, resulting in an increased NADH/NAD+ ratio, alteration of cellular redox status and decreased NAD+-dependent enzyme activities (Bailey & Cunningham, 2002). In addition, metabolism of alcohol by Cyp2E1 results in production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which also leads to liver injury (Cederbaum, Lu, & Wu, 2009).

In addition to the oxidative metabolism, a minimal portion of alcohol can also be metabolized via two non-oxidative pathways. Alcohol can directly interact with fatty acid and generates fatty acid ethyl ester (FAEE) through FAEE synthase (Zelner et al., 2013). FAEE was thought to have minor effects and mainly considered as a diagnostic marker, but increasing evidences showed that FAEE exacerbates alcohol-induced injury in various tissues including liver (Wu et al., 2006), pancreas (Werner et al., 2002; Wu, Bhopale, Ansari, & Kaphalia, 2008), and heart (Beckemeier & Bora, 1998; Wu et al., 2008, 2006). FAEE induces mitochondria damage by binding to mitochondria membrane and uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation (Lange & Sobel, 1983). Alcohol also reacts with phospholipase D (PLD), which normally breaks down phospholipids to generate phosphatidic acid (PA). The reaction of ethanol with PLD leads to the formation of phosphatidyl ethanol, which is poorly metabolized and its impact on cellular functions remain to be established (Zakhari, 2006).

3. Autophagy

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved degradation pathway for cytosolic macromolecules and damaged/excess organelles. It is first described by de Duve and Wattiaux in the 1960s (De Duve & Wattiaux, 1966). However, until 1990s, the molecular characterization of autophagy began by Ohsumi’s laboratory using yeast genetic screens that led to the discovery of a group of essential autophagy-related genes (Atg) in yeast (Thumm et al., 1994; Tsukada & Ohsumi, 1993). So far, more than 30 different Atg have been identified in yeast, and most of them are found to be highly conserved in mammals. The process of autophagy starts from the formation of a transient double-membrane structure, the phagophore, which is the active sequestering compartment. Following the expansion and closure, the phagophore becomes a complete autophagosome. Autophagosomes then subsequently fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes where the enwrapped contents are degraded by lysosomal enzymes (Klionsky & Emr, 2000; Nakatogawa, Suzuki, Kamada, & Ohsumi, 2009; Parzych & Klionsky, 2014). Several multi-molecular complexes have been found to contribute to autophagosome formation including: (1) ULK1 protein-kinase complex, (2) Becline-VPS34 class III PI3K complex, (3) Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 and Atg8/LC3 conjugation systems, and (4) Atg9-Atg2-Atg18 complex.

The ULK1 (Unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 or 2, mammalian homologs of Atg1, hereafter we only refer to as ULK1) kinase complex is the most upstream component of the core autophagy machinery. In mammalian cells, this complex is composed of ULK1, Atg13, RB1CC1/FIP200 (RB1-inducible coiled-coil 1, a putative yeast Atg17 homolog) and C12orf44/Atg101 (Mizushima, 2010). The initiation of autophagy requires the formation of the ULK1 kinase complex at the phagophore assembly site (PAS) to allow the recruitment and activation of other Atg proteins. ULK1 interacts with Atg13, which directly binds to FIP200 and mediates the interaction between FIP200 and ULK1. The activity of ULK1 kinase complex can be regulated by both mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). When nutrients are sufficient, mTORC1 is activated and negatively regulates autophagy by directly phosphorylating ULK1 (S757) and inhibiting its activity (Egan, Kim, Shaw, & Guan, 2011, Egan et al., 2011; Kim, Kundu, Viollet, & Guan, 2011). In contrast, when cells suffer from energy deficiency, AMPK is activated and phosphorylates ULK1 at different sites (S317, S467, S555, T574, S637 and S777), which activates ULK1 to promote autophagy resulting in the catabolic degradation of cellular components to generate ATP (Egan, Kim, et al., 2011, Egan, Shackelford, et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011; Loffler et al., 2011).

Once activated, ULK1 further phosphorylates Beclin1 (mammalian homologs of Atg6) on S14 (Russell et al., 2013). Beclin1 is a component of the autophagy-promoting class III phosphoinositide 3 (PI3)-kinase complexes, which also contains Atg14L, p150 (the yeast ortholog is Vps15) and the class-III PI3 kinase VPS34 (Kihara, Noda, Ishihara, & Ohsumi, 2001). This complex is responsible for the production of phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns3P) directly from phosphatidylinositol (Burman & Ktistakis, 2010). PtdIns3P serves as a landmark on the membrane to recruit other factors, such as Atg18, involved in the process of autophagosome formation (Obara, Sekito, Niimi, & Ohsumi, 2008). After the activation of Beclin1-VPS34 class III PI3K complex, phagophore expands and elongates by membrane addition, which is accomplished by the Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 and Atg8/LC3 conjugation systems.

These two essential ubiquitin-like (Ubl) conjugation systems involve the Ubl proteins Atg12 and microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B light chain 3 (MAP1-LC3 or LC3, a homolog of Atg8) (Ohsumi, 2001). In the ubiquitin system, Atg12 is the first Ubl and its carboxy-terminal glycine is first activated by an E1-like enzyme, Atg7. Subsequently, Atg12 is transferred to an E2-like conjugating enzyme, Atg10, and conjugates with Atg5. This conjugation requires no known E3 enzyme, and further binds to Atg16L1 (the ortholog of yeast Atg16) to form the Atg12-Atg5-Atg16L1 complex. The Atg12-Atg5-Atg16L1 complex localizes to the isolation membrane throughout its elongation process and serves as an E3 ligase to promote LC3 conjugation with phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). Nascent LC3 is first processed by a protease, Atg4, to expose its C-terminus glycine, which is called LC3-I form that resides in the cytosol. LC3-I is then further activated by E1-like enzyme, Atg7, then transferred to an E2-like conjugating enzyme, Atg3. Finally, LC3 conjugates with PE to form a membrane associated LC3-II form, with the Atg12-Atg5-Atg16L1 complex participating as an E3-like ligase.

In addition to Ubl conjugation system, a Atg9-Atg2-Atg18 complex containing the core protein Atg9, Atg2 and WIPI1/2 (mammalian homologs of Atg18) acts as a cycling system. It contributes to the elongation of the phagophore (Polson et al., 2010). Atg9 is thought to participate in membrane delivery from donor sources, such as the trans-Golgi network or late endosomes, to the expanding phagophore. The movement of Atg9 is dependent on the activity of the ULK1, class III PI3K VPS34, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK/p38) (Papinski et al., 2014; Webber & Tooze, 2010). Eventually, the expanding membrane closes around its cargo to form a complete autophagosome. The latter moves along microtubules in a dynein motor-dependent manner and cluster closed to the microtubule-organizing center near the nucleus, where it fuses with a lysosome to form an autolysosome. The mechanism that controls the timing of fusion is not known at present. UVRAG, which is part of the PtdIns3K complex, can activate the GTPase Rab7, which promotes fusion with lysosomes (Jager et al., 2004; Liang et al., 2008). Other components of the SNARE (soluble NSF [N-ethyl-maleimide-sensitive fusion protein] attachment protein receptor) family proteins, such as VAMP7, VAMP8, VAMP9 and STX17/syntaxin 17, are also implicated in autophagosome fusion with lysosomes (Fader, Sanchez, Mestre, & Colombo, 2009; Furuta, Fujita, Noda, Yoshimori, & Amano, 2010; Itakura, Kishi-Itakura, & Mizushima, 2012). In addition, LAMP-2A, a lysosomal membrane protein, is also required for the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes. Lack of LAMP-2A prevents the localization of STX17 and SNAP-29 on the autophagosomes resulting in defective fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes (Hubert et al., 2016). After the sequestered cargo is delivered inside the lysosome, it is broken down by resident hydrolases of the lysosome and the resulting macromolecules are released back into the cytosol as new energy sources for cell survival. In addition to providing new building blocks and energy sources, autophagy also helps to remove damaged organelles such as mitochondria as another important mechanism for cell survival (Williams & Ding, 2018).

4. Autophagy in ALD mouse models

While many species have been used to study ALD including baboons, pigs and rats, mice have been used predominantly in current ALD research. This is due to the availability of numerous transgenic and knockout mice that can easily help scientists determine the role of a particular molecule or signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of ALD. In addition, mice have more than 85% genetic similarity to humans, and their physiology and genetics have been extensively studied. Moreover, mice can reproduce quickly and are relatively inexpensive compared to baboons and pigs. Several mouse models have been used to study alcoholic liver injury that include acute oral gavage, ad libitum oral alcohol in drinking water, intragastric infusion (Tsukamoto-French model) (Tsukamoto, Reidelberger, French, & Largman, 1984), chronic Lieber-DeCarli diet ethanol feeding and the most recent NIAAA chronic-binge ethanol model, which was developed by Bin Gao’s group (hereafter referred to as Gao-binge model).

4.1. Acute alcohol exposure

Alcohol binge drinking can result in mitochondrial damage, inhibition of insulin signaling, steatosis, apoptotic and necrotic cell death, all of which can be regulated by autophagy. Acute alcohol treatment significantly increased both mRNA and protein levels of various essential Atg in mouse livers (Ni, Du, You, & Ding, 2013). Induction of the expression of Atg in hepatocytes by acute alcohol is mediated by the transcription factor FoxO3 and hypoxia-inducing factor-1 beta (Ni et al., 2014, 2013). Using GFP-LC3 transgenic mice, we demonstrated that acute ethanol treatment induced a significant elevation of GFP-LC3 positive autophagosomes and autophagic flux in mouse livers. Similarly, an enrichment of PE-conjugated LC3 was particularly found in the LAMP1-positive heavy membrane fraction, where lysosomes are located, indicating that autophagosomes have been fused with the lysosomes to form the degradative autolysosomes (Ding et al., 2010; Ding, Li, & Yin, 2011; Ding, Manley, & Ni, 2011). Electron microscope (EM) analysis also indicated an accumulation of autophagosomes in acute alcohol treated mouse livers. This induction of autophagy is suppressed after siRNA-mediated knockdown of Atg7 (Ding et al., 2010). In accordance with our findings, several recent studies also found that acute alcohol exposure induces autophagy in mouse livers (Lin et al., 2013; Thomes et al., 2012).

4.2. Chronic alcohol exposure

In a chronic alcohol mouse model, male SV129 mice were fed with Lieber-DeCarli liquid dextrose diet containing gradually increased alcohol for 4 weeks. Fatty liver, elevation of Cyp2E1 and oxidative stress were induced by alcohol feeding in these mice (Lu & Cederbaum, 2015). Inhibition of autophagy by administration of 3-methyladenine (3-MA) enhanced alcohol-induced hepatotoxicity, steatosis and oxidant stress. In contrast, activation of autophagy by rapamycin blunted the elevated steatosis produced by alcohol feeding (Lu & Cederbaum, 2015). In similar studies from another research group, GFP-LC3 transgenic mice were fed control and ethanol-containing liquid diets for 4–6 weeks. Alcohol feeding increased hepatomegaly, steatosis and elevated liver proteins, suggesting slower catabolism in alcohol fed-GFP-LC3 mice (Lin et al., 2013; Thomes et al., 2012). Hepatocytes from mice chronically consuming alcohol exhibited a fourfold rise in GFP-LC3 puncta, which represents autophagosomes, compared with hepatocytes from pair-fed control mice. Cyp2E1 activity and content are elevated in alcohol-fed mice, suggesting enhanced ethanol metabolism may contribute to the augmented autophagosome contents. It should be noted that hepatic proteasome activity was also suppressed in livers of alcohol-fed mice, which may also contribute to a portion of the net protein gain in the liver (Thomes et al., 2012). There is evidence that chronic ethanol consumption also inhibits the degradative phase (i.e. autophagosome degradation by lysosomes) of autophagy, which could account, in part, for the rise in autophagosomes (Thomes, Trambly, Fox, Tuma, & Donohue, 2015).

Isolated primary hepatocytes from rats after 6 weeks of Lieber-Decarli ethanol feeding showed decreased lipid droplet (LD) breakdown in response to starvation. Mechanistically, it is found that chronic ethanol exposure inhibited lysosome mobility and decreased Rab7 activity. Moreover, chronic ethanol also decreased Src kinase activity and Dyn2 (a GTPase involved in scission of cell membrane and formation of microtubule bundle) activities resulting decreased lysosome-mediated LD turnover (Li & Ding, 2017; Rasineni et al., 2017; Schroeder et al., 2015; Schulze, Drizyte, Casey, & McNiven, 2017, Schulze et al., 2017).

4.3. Gao-binge model

Most recently, a novel mouse model (Gao-binge model or NIAAA model) that combines chronic alcohol feeding with acute alcohol exposure was developed by Bin Gao’s group (Bertola, Mathews, Ki, Wang, & Gao, 2013, Bertola, Park, & Gao, 2013). In this model, mice are fed a control Lieber-DeCarli liquid diet for 5-days before switching them to a 10-days ethanol Lieber-DeCarli diet (1–5%) followed by one oral gavage of ethanol (31.5% v/v, 5 g/kg) in the morning of day 11 for 9h. Control animals are fed a calorie-matched diet and receive a maltose dextran gavage (45%) on day 11 (Bertola, Mathews, et al., 2013; Bertola, Park, & Gao, 2013). In this model, mice showed markedly elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and steatosis along with significant inflammation in mouse livers compared with either the chronic 10-days feeding or the acute binge alone (Bertola, Mathews, et al., 2013; Bertola, Park, & Gao, 2013).

Using GFP-LC3 transgenic mice, we recently characterized autophagic flux in the mouse livers after Gao-binge treatment (Chao, Ni, & Ding, 2018). We found that the number of GFP-LC3 puncta increased in hepatocytes of ethanol feeding plus binge mice. In the presence of leupeptin, a lysosomal inhibitor that blocks autolysosomal degradation, the number of GFP-LC3 puncta and levels of GFP-LC3-II further increased compared with either leupeptin alone or ethanol group alone, suggesting that Gao-binge alcohol increases autophagic flux in mouse livers. Increased autophagic flux often leads to the degradation of p62, a substrate protein of autophagy. However, to our surprise, the levels of hepatic p62 were not altered in Gao-binge alcohol-treated mice, suggesting that Gao-binge alcohol-induced autophagy is not sufficient to degrade p62. Subsequently, we found that Gao-binge alcohol decreased hepatic TFEB, a master transcription factor that regulates lysosomal biogenesis, resulting in the decreased lysosome numbers in hepatocytes. Decreased hepatic TFEB is likely mediated by the activation of mTOR and pharmacological inhibition of mTOR partially rescued TFEB signaling and protected against Gao-binge alcohol-induced steatosis and liver injury. Overexpression of TFEB enhanced not only hepatic lysosomal biogenesis but also mitochondrial biogenesis as overexpression of TFEB also markedly upregulated PGC-1α expression. As a result, activation of TFEB protected against Gao-binge alcohol-induced steatosis and liver injury. More importantly, we also found that nuclear TFEB levels decreased in human ALD liver samples compared with healthy human liver donors (Chao et al., 2018). These findings suggest that targeting TFEB may be a promising strategy for treating ALD.

5. Potential therapeutic approaches to treat ALD by modulating autophagy

Alcohol consumption can alter autophagy and modulating autophagy may help to improve the pathogenesis of ALD (Ding et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2013; Thomes et al., 2012; Wu, Wang, Zhou, Yang, & Cederbaum, 2012). Suppression of autophagy with pharmacologic agent chloroquine or siRNA against Atg7 significantly increases hepatocyte apoptosis and liver injury (Ding et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2013). In contrast, pharmacological activation of autophagy protects against alcohol-induced steatosis and liver injury (Chao, Ni, & Ding, 2018; Ding et al., 2010). How autophagy protects against alcohol-induced liver injury is not fully understood, but it could involve selective degradation of damaged mitochondrial and/or lipids (Ding, Li, & Yin, 2011, Ding, Manley, & Ni, 2011; Williams, Ni, Ding, & Ding, 2015; Williams & Ding, 2015).

Autophagy can be either selective or nonselective. Traditionally autophagy is viewed as a non-selective process under nutrient and/or energy deprivation condition. While nonselective autophagic bulk degradation of cellular components provides nutrients and energy to support anabolic metabolism in response to starvation, selective autophagy targets specific substrates and organelles such as intracellular aggregated proteins, mitochondria (mitophagy), endoplasmic reticulum (ER-phagy), pathogens, peroxisomes (pexophagy), ribosomes (ribophagy) and lipid droplets (lipophagy), in either nutrient rich or poor conditions (Green & Levine, 2014; Reggiori, Komatsu, Finley, & Simonsen, 2012). The selective functions of autophagy indicate that it is important for maintaining cellular homeostasis by removing superfluous or injured organelles.

5.1. Mitophagy

The selectively removal of damaged mitochondria is a specific form of autophagy termed as mitophagy. Mitophagy is mediated by autophagy receptor proteins, which typically can bind both damaged mitochondria (usually are ubiquitinated) and LC3-decorated phagophores (Behrends & Fulda, 2012; Ding & Yin, 2012; Ni, Williams, & Ding, 2015; Williams & Ding, 2018).

Several signaling pathways are responsible for the progression of mitophagy, among which, so far, the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin pathway is the best characterized. PINK1, containing a mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS), is a 64-kDa mitochondrial serine/threonine kinase and is recruited to mitochondria immediately after synthesis. In healthy mitochondria, PINK1 is imported through the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes via the translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane (TOM) complex and translocase of the inner mitochondrial membrane (TIM) complex respectively. It is then first processed by the matrix processing peptidase (Greene et al., 2012) and then cleaved between amino acids A103 and F104 by the inner mitochondrial membrane protease PARL (Deas et al., 2011; Jin et al., 2010; Meissner, Lorenz, Weihofen, Selkoe, & Lemberg, 2011). The new truncated form of PINK1 is released into the cytosol for N-terminal recognition and degraded by the proteasome (Yamano & Youle, 2013). The cleaved PINK1 fragments in the cytosol may also inhibit Parkin translocation to mitochondria (Fedorowicz et al., 2014). When mitochondria are damaged, in particular with depolarized mitochondrial membrane potential, PINK1 is no longer imported into the inner membrane or cleaved by PARL, resulting in its accumulation on the outer mitochondrial membrane (Matsuda et al., 2010; Narendra et al., 2010; Vives-Bauza et al., 2010). The accumulated PINK1 on the outer mitochondrial membrane then phosphorylates Ser65 within Parkin’s UBL domain that leads to the recruitment and tethering of Parkin to mitochondria. Besides of Parkin phosphorylation, PINK1 also phosphorylates Ser65 on ubiquitin and promotes the Parkin E3 ligase activity resulting in greater Parkin-induced ubiquitination of outer mitochondrial membrane protein, including the mitochondrial fusion proteins mitofusin 1 (Mfn1) and Mfn2, the mitochondrial trafficking protein Miro1, TOM20, and the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) (Koyano et al., 2014). Degradation of Mfn1/Mfn2 causes imbalance of mitochondrial dynamic, resulting in mitochondrial fragmentation (Chan et al., 2011; Gegg et al., 2010; Geisler et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2011). Ubiquitination and degradation of Miro1 lead to mitochondrial arrest, which can separate damaged mitochondria from healthy mitochondria. Both of mitochondrial fragmentation and mitochondrial arrest may further facilitate mitophagy since smaller mitochondria are likely more readily to be engulfed by autophagosomes (Ni et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2011).

Mitochondrial damage is well defined in alcoholic liver disease (Serviddio, Bellanti, Sastre, Vendemiale, & Altomare, 2010; Williams & Ding, 2015). As we discussed above, during the major oxidative metabolism of alcohol, excess NADH is generated and oxidized indirectly by mitochondrial electron transport system. The excessive amount of NADH and thus the reducing capacity in the mitochondrial electron transport system is thought to cause an increased leakage of mitochondrial ROS, causing alcohol-induced oxidative stress in livers. This has been shown to alter oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial proteome and mitochondrial dynamics. Mitochondrial fragmentation was observed in ethanol-treated hepatocytes (Ding, Li, & Yin, 2011; Ding, Manley, & Ni, 2011). Ethanol treatment also increased the sensitivity of mitochondrial permeability transition (King et al., 2014) and mitochondrial DNA depletion in livers of ethanol-treated mouse (Mansouri et al., 1999; Mansouri, Demeilliers, Amsellem, Pessayre, & Fromenty, 2001). Chronic ethanol consumption enhances oxidative damage to mtDNA along with increased strand breakage, and other alterations in the structural integrity of mitochondrial DNA (Cahill, Stabley, Wang, & Hoek, 1999), which has been thought to cause ethanol-related liver pathology. Mitophagy may be important to eliminate dysfunctional and potentially deleterious mitochondria (Williams & Ding, 2015). Alcohol-induced autophagy can selectively target to the damaged mitochondria as observed in both acute (Ding et al., 2010; Ding, Li, & Yin, 2011; Ding, Manley, & Ni, 2011) and chronic (Eid, Ito, Maemura, & Otsuki, 2013) as well as Gao-binge alcohol (Williams et al., 2015). Alcohol-induced GFP-LC3 positive autophagosomes specifically envelop mitochondria have been documented (Ding et al., 2010; Ding, Li, & Yin, 2011; Ding, Manley, & Ni, 2011). What is the mechanism of this selectivity has yet to be determined. It is possible that the PINK1-Parkin signaling pathway may be involved. Immunoelectron microscopic studies indicated that expression of PINK1 was increased in mitochondria from ethanol-treated rats (Eid et al., 2013). To investigate the role of Parkin in alcohol-induced liver injury and steatosis, we recently used WT and Parkin KO mice that were treated with acute and Gao-binge alcohol model (Williams et al., 2015). We demonstrated that the translocation of Parkin to mitochondria and mitophagy increased after Gao-binge alcohol treatment in mouse livers, but not in acute alcohol treated mouse livers (Williams et al., 2015). Alcohol caused greater mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress in Parkin KO mouse livers compared with WT mouse livers. Furthermore, Parkin KO mice had decreased mitophagy, β-oxidation, mitochondrial respiration, and cytochrome c oxidase activity after acute alcohol treatment compared with WT mice. Interestingly, liver mitochondria seemed to be able to adapt to alcohol treatment, but mitochondria in Parkin KO mouse liver had less capacity to adapt to Gao-binge treatment compared with mitochondria in WT mouse liver. These data suggest that Parkin-mediated mitophagy may be protective against alcohol-induced liver injury by removing alcohol-induced damaged mitochondria. In addition to decreasing mitophagy, after alcohol treatment, Parkin KO mice had severely swollen and damaged mitochondria that lacked cristae, which were not seen in WT mice, suggesting that Parkin may have other roles in maintaining healthy mitochondria population (Williams et al., 2015). Other group also found that alcohol-mediated oxidative stress can also cause the translocation of the inducible form of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) to mitochondria, which in turn increases the recruitment of LC3 to the mitochondria (Bansal, Biswas, & Avadhani, 2014). The recognition of the damaged mitochondria could be mediated by multiple mechanisms after alcohol exposure and elucidation of these mechanisms is one of the important future works.

5.2. Removal of lipid droplet by autophagy

Excessive accumulation of hepatic triglycerides and fatty acids is one of the main features of alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Free fatty acids can be detrimental to hepatocytes. The esterified lipids are sequestered in LD and would be considered harmless, although de-esterification can occur, which would increase levels of cellular free fatty acids. Autophagosomes can transport the content of LD to the lysosome, in which lipids are degraded by the lysosomal acid lipase. This process, known as lipophagy (Singh et al., 2009), is still far from a complete understanding. Nevertheless, lipophagy occurs in alcohol-treated mouse livers although it could be impaired or insufficient (Ding, Li, & Yin, 2011; Ding, Manley, & Ni, 2011; Rasineni et al., 2017). Alcohol-induced GFP-LC3 positive autophagosomes specifically envelop LD have been observed in vivo and in vitro (Ding et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2013). While activating autophagy by rapamycin reduced hepatic TG level, inhibiting autophagy by chloroquine elevated hepatic TG level in both acute and chronic ALD models (Ding et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2013). Notably, similar observations can be made in a HFD-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) model (Lin et al., 2013), suggesting that a common mechanism of lipophagy may be involved in the removal of lipids. In addition to the canonical lipophagy that may involve the autophagosomes, more recent evidence suggests that β-adrenergic (β-AR)/cAMP pathway-mediated LD lipolysis via cytosolic adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) may be important for LD turnover (Schott et al., 2017). ATGL-mediated lipolysis may breakdown large LD into small LD that are favorable for the engulfment of autophagosomes that deliver the LD to lysosomes. Alternatively, small LD can be enveloped directly by lysosomes via microlipophagy or nanolipophagy (Schulze, Drizyte, et al., 2017; Schulze, Rasineni, et al., 2017). Indeed, we recently found that LD can directly penetrate into single membrane vesicles in hepatocytes during fasting (Li et al., 2018). Our unpublished data also show that the majority of isolated lysosomes from Gao-binge-treated mouse livers contain LD, suggesting a role of microlipophagy in regulating LD homeostasis. Interestingly, chronic ethanol exposure impaired (β-AR)/cAMP-mediated LD lipolysis and in turn blocked the mobilization of LD to lysosomes (Schott et al., 2017). Impaired LD lipolysis together with the impaired TFEB-mediated lysosomal biogenesis thus could be major contributors for the hepatic LD accumulation in the development of ALD.

5.3. Removal of protein aggregates by autophagy

It is well documented that chronic alcohol consumption can inhibit proteasome activity and induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress resulting in the accumulation of aggregated proteins, which are called Mallory-Denk bodies (MDB) in the liver (Baraona, Leo, Borowsky, & Lieber, 1975; Donohue et al., 2007; Ji, 2008; Kaplowitz & Ji, 2006; Riley et al., 2002; Zatloukal et al., 2007). Early studies showed the rate of hepatic protein degradation in ethanol-fed animals declined significantly (Donohue, Zetterman, & Tuma, 1989), which might be due to declines in both proteasome and autophagy function, contributing to the development of hepatomegaly and the formation of MDB. These cytosolic inclusion bodies are characteristic hall markers of ALD, which are also often seen in autophagy deficiency. MDB is enriched with cytokeratin 8 and 18, and in association with other proteins including ubiquitin and p62 (Lahiri et al., 2016). p62 is able to polymerize via an N-terminal PB1 domain, and interacts with ubiquitinated proteins via the C-terminal UBA domain. p62 also binds directly to LC3 via its LC3 interacting region (LIR). p62 is an autophagy substrate protein and usually degraded by autophagy. p62 also acts as an autophagy receptor for selective autophagy such as selective autophagy for protein aggregates via its interaction with ubiquitinated proteins and LC3. The presence of MDB suggests that autophagy activity may be impaired in chronic alcohol consumption. Indeed, pharmacological activation autophagy by rapamycin, an mTORC1 inhibitor, increased the clearance of MDB in a keratin 8-overexpressing transgenic mouse model of MDB pathology (Harada, Hanada, Toivola, Ghori, & Omary, 2008). In another classical protein aggregates-induced liver injury model, the α1-antitrypsin deficiency, carbamazepine (CBZ) induced autophagy and decreased the hepatic load of α1-antitrypsin mutant proteins as well as hepatic fibrosis (Hidvegi et al., 2010). In contrast to rapamycin, CBZ induces autophagy in the liver independent of mTOR, suggesting that various autophagy pathways could be targeted to remove aggregated proteins and/or to treat liver diseases including ALD.

6. Conclusion

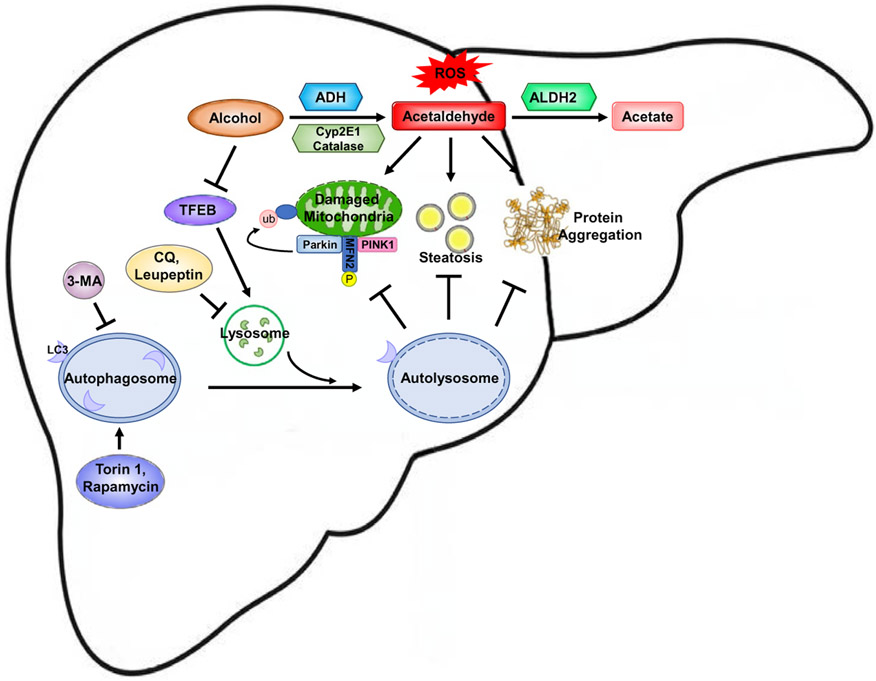

In summary, increasing evidence has indicated that alcohol may increase the formation of autophagosomes but may also impair either the lysosome functions or lysosomal biogenesis resulting in insufficient autophagy in hepatocytes. Pharmacological targeting lysosomal biogenesis or autophagy may protect against alcohol-induced liver injury by removing damaged mitochondria, protein aggregates and LD. Since ALD is a chronic liver disease, it remains to be studied whether activation of lysosomal degradation and autophagy can reverse the chronic alcoholic pathogenesis such as fibrosis and inflammation by promoting liver repair and regeneration. The possible molecular events associated with autophagy that could be altered by alcohol consumption and the possible targets that can be manipulated to prevent and treat ALD are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A proposed model for the molecular events and mechanisms underlying the protection of autophagy against alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol is mainly metabolized in the liver through a major oxidative pathway. In this pathway, alcohol is catalyzed by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), which converts alcohol into highly reactive metabolite, acetaldehyde. A small portion of alcohol can also be oxidized into acetaldehyde by cytochrome P450 family 2, subfamily E, polypeptide 1 (Cyp2E1) and catalase. Acetaldehyde is further metabolized by mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) into more harmless acetate. Alcohol consumption leads to mitochondria damage due to increased reactive oxygen species, lipid accumulation and formation of protein aggregates. Autophagy can be induced as an adapted protective mechanism to remove damaged mitochondria, accumulated lipid droplets and protein aggregates. The removal of damaged mitochondria is through selective mitophagy, which is mediated by the PINK1/Parkin pathway that promotes mitochondrial ubiquitination. However, chronic alcohol drinking inhibits the activity of transcription factor EB, which is a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy, leading to insufficient autophagy. Pharmacological induction of autophagy (Torin 1 or rapamycin) or inhibition of autophagy (Leupeptin, CQ or 3-MA) protects or exacerbates alcohol-induced liver injury and steatosis, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by NIH grants: R01 AA020518, R01 DK102142, U01 AA024733 and P20GM103549 & P30GM118247 (W.X.D.), and CSC (No. 201708040024) (X.C.).

Abbreviations

- 3-MA

3-methyladenine

- ADH

alcohol dehydrogenase

- AH

alcoholic hepatitis

- ALD

alcoholic liver disease

- ALDH1/2

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1/2

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- Atg

autophagy-related gene

- CYP2E1

cytochrome P450 2E1

- EM

electron microscope

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FAEE

fatty acid ethyl ester

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- KO

knockout

- Lamp1

lysosome-associated membrane protein 1

- LC3/MAP1-LC3

microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B light chain 3

- LIR

LC3 interacting region

- MAPK14/p38

mitogen-activated protein kinase 14

- MDB

Mallory-Denk bodies

- Mfn1

mitofusin 1

- mTORC1

mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1

- MTS

mitochondrial targeting sequence

- NAD+

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NIAAA

National Institute on alcohol abuse and alcoholism

- PA

phosphatidic acid

- PAS

phagophore assembly site

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PINK1

phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-induced kinase 1

- PLD

phospholipase D

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PtdIns3P

phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate

- RB1CC1/FIP200

RB1-inducible coiled-coil 1

- SNARE

soluble NSF [N-ethyl-maleimide-sensitive fusion protein] attachment protein receptor

- TFEB

transcription factor EB

- TIM

translocase of mitochondrial inner membrane

- TOM

translocase of mitochondrial outer membrane

- Ubl

ubiquitin-like

- ULK1/2

Unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1/2

- VDAC

voltage-dependent anion channel

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bailey SM, & Cunningham CC (2002). Contribution of mitochondria to oxidative stress associated with alcoholic liver disease. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 32, 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal S, Biswas G, & Avadhani NG (2014). Mitochondria-targeted heme oxygenase-1 induces oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in macrophages, kidney fibroblasts and in chronic alcohol hepatotoxicity. Redox Biology, 2, 273–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraona E, Leo MA, Borowsky SA, & Lieber CS (1975). Alcoholic hepatomegaly: Accumulation of protein in the liver. Science, 190, 794–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckemeier ME, & Bora PS (1998). Fatty acid ethyl esters: Potentially toxic products of myocardial ethanol metabolism. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 30, 2487–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrends C, & Fulda S (2012). Receptor proteins in selective autophagy. International Journal of Cell Biology, 2012, 673290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertola A, Mathews S, Ki SH, Wang H, & Gao B (2013). Mouse model of chronic and binge ethanol feeding (the NIAAA model). Nature Protocols, 8, 627–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertola A, Park O, & Gao B (2013). Chronic plus binge ethanol feeding synergistically induces neutrophil infiltration and liver injury in mice: A critical role for E-selectin. Hepatology, 58, 1814–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman C, & Ktistakis NT (2010). Regulation of autophagy by phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. FEBS Letters, 584, 1302–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill A, Stabley GJ, Wang X, & Hoek JB (1999). Chronic ethanol consumption causes alterations in the structural integrity of mitochondrial DNA in aged rats. Hepatology, 30, 881–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederbaum AI (2012). Alcohol metabolism. Clinics in Liver Disease, 16, 667–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederbaum AI, Lu Y, & Wu D (2009). Role of oxidative stress in alcohol-induced liver injury. Archives of Toxicology, 83, 519–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan NC, Salazar AM, Pham AH, Sweredoski MJ, Kolawa NJ, Graham RL, et al. (2011). Broad activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by Parkin is critical for mitophagy. Human Molecular Genetics, 20, 1726–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao X, Ni HM, & Ding WX (2018). Insufficient autophagy: A novel autophagic flux scenario uncovered by impaired liver TFEB-mediated lysosomal biogenesis from chronic alcohol-drinking mice. Autophagy, 14, 1646–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao X, Wang S, Zhao K, Li Y, Williams JA, Li T, et al. (2018). Impaired TFEB-mediated lysosome biogenesis and autophagy promote chronic ethanol-induced liver injury and steatosis in mice. Gastroenterology, 155, 865–879.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb DW, Matsumoto M, Chang D, & You M (2004). Overview of the role of alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase and their variants in the genesis of alcohol-related pathology. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 63, 49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja MJ, Ding WX, Donohue TM Jr., Friedman SL, Kim JS, Komatsu M, et al. (2013). Functions of autophagy in normal and diseased liver. Autophagy, 9, 1131–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Duve C, & Wattiaux R (1966). Functions of lysosomes. Annual Review of Physiology, 28, 435–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deas E, Plun-Favreau H, Gandhi S, Desmond H, Kjaer S, Loh SH, et al. (2011). PINK1 cleavage at position A103 by the mitochondrial protease PARL. Human Molecular Genetics, 20, 867–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding WX (2010). Role of autophagy in liver physiology and pathophysiology. World Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1, 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding WX, Li M, Chen X, Ni HM, Lin CW, Gao W, et al. (2010). Autophagy reduces acute ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity and steatosis in mice. Gastroenterology, 139, 1740–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding WX, Li M, & Yin XM (2011). Selective taste of ethanol-induced autophagy for mitochondria and lipid droplets. Autophagy, 7, 248–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding WX, Manley S, & Ni HM (2011). The emerging role of autophagy in alcoholic liver disease. Experimental Biology and Medicine (Maywood, N.J.), 236, 546–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding WX, & Yin XM (2012). Mitophagy: Mechanisms, pathophysiological roles, and analysis. Biological Chemistry, 393, 547–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolganiuc A, Thomes PG, Ding WX, Lemasters JJ, & Donohue TM Jr. (2012). Autophagy in alcohol-induced liver diseases. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 36, 1301–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue TM Jr., Cederbaum AI, French SW, Barve S, Gao B, & Osna NA (2007). Role of the proteasome in ethanol-induced liver pathology. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 31, 1446–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue TM Jr., Zetterman RK, & Tuma DJ (1989). Effect of chronic ethanol administration on protein catabolism in rat liver. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 13, 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan D, Kim J, Shaw RJ, & Guan KL (2011). The autophagy initiating kinase ULK1 is regulated via opposing phosphorylation by AMPK and mTOR. Autophagy, 7, 643–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W, et al. (2011). Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science, 331, 456–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid N, Ito Y, Maemura K, & Otsuki Y (2013). Elevated autophagic sequestration of mitochondria and lipid droplets in steatotic hepatocytes of chronic ethanol-treated rats: An immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study. Journal of Molecular Histology, 44, 311–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fader CM, Sanchez DG, Mestre MB, & Colombo MI (2009). TI-VAMP/VAMP7 and VAMP3/cellubrevin: Two v-SNARE proteins involved in specific steps of the autophagy/multivesicular body pathways. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1793, 1901–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorowicz MA, de Vries-Schneider RL, Rub C, Becker D, Huang Y, Zhou C, et al. (2014). Cytosolic cleaved PINK1 represses Parkin translocation to mitochondria and mitophagy. EMBO Reports, 15, 86–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta N, Fujita N, Noda T, Yoshimori T, & Amano A (2010). Combinational soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor proteins VAMP8 and Vti1b mediate fusion of antimicrobial and canonical autophagosomes with lysosomes. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 21, 1001–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, & Bataller R (2011). Alcoholic liver disease: Pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology, 141, 1572–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegg ME, Cooper JM, Chau KY, Rojo M, Schapira AH, & Taanman JW (2010). Mitofusin 1 and mitofusin 2 are ubiquitinated in a PINK1/parkin-dependent manner upon induction of mitophagy. Human Molecular Genetics, 19, 4861–4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Holmstrom KM, Skujat D, Fiesel FC, Rothfuss OC, Kahle PJ, et al. (2010). PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nature Cell Biology, 12, 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, & Levine B (2014). To be or not to be? How selective autophagy and cell death govern cell fate. Cell, 157, 65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AW, Grenier K, Aguileta MA, Muise S, Farazifard R, Haque ME, et al. (2012). Mitochondrial processing peptidase regulates PINK1 processing, import and Parkin recruitment. EMBO Reports, 13, 378–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada M, Hanada S, Toivola DM, Ghori N, & Omary MB (2008). Autophagy activation by rapamycin eliminates mouse Mallory-Denk bodies and blocks their proteasome inhibitor-mediated formation. Hepatology, 47, 2026–2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidvegi T, Ewing M, Hale P, Dippold C, Beckett C, Kemp C, et al. (2010). An autophagy-enhancing drug promotes degradation of mutant alpha1-antitrypsin Z and reduces hepatic fibrosis. Science, 329, 229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert V, Peschel A, Langer B, Groger M, Rees A, & Kain R (2016). LAMP-2 is required for incorporating syntaxin-17 into autophagosomes and for their fusion with lysosomes. Biology Open, 5, 1516–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E, Kishi-Itakura C, & Mizushima N (2012). The hairpin-type tail-anchored SNARE syntaxin 17 targets to autophagosomes for fusion with endosomes/lysosomes. Cell, 151, 1256–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager S, Bucci C, Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E, Saftig P, et al. (2004). Role for Rab7 in maturation of late autophagic vacuoles. Journal of Cell Science, 117, 4837–4848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C (2008). Dissection of endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver injury. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 23(Suppl. 1), S16–S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SM, Lazarou M, Wang C, Kane LA, Narendra DP, & Youle RJ (2010). Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. The Journal of Cell Biology, 191, 933–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz N, & Ji C (2006). Unfolding new mechanisms of alcoholic liver disease in the endoplasmic reticulum. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 21(Suppl. 3), S7–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A, Noda T, Ishihara N, & Ohsumi Y (2001). Two distinct Vps34 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes function in autophagy and carboxypeptidase Y sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of Cell Biology, 152, 519–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, & Guan KL (2011). AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nature Cell Biology, 13, 132–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AL, Swain TM, Mao Z, Udoh US, Oliva CR, Betancourt AM, et al. (2014). Involvement of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in chronic ethanol-mediated liver injury in mice. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 306, G265–G277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, & Emr SD (2000). Autophagy as a regulated pathway of cellular degradation. Science, 290, 1717–1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyano F, Okatsu K, Kosako H, Tamura Y, Go E, Kimura M, et al. (2014). Ubiquitin is phosphorylated by PINK1 to activate parkin. Nature, 510, 162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri P, Schmidt V, Smole C, Kufferath I, Denk H, Strnad P, et al. (2016). p62/Sequestosome-1 is indispensable for maturation and stabilization of Mallory-Denk bodies. PLoS One, 11, e0161083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange LG, & Sobel BE (1983). Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by fatty acid ethyl esters, myocardial metabolites of ethanol. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 72, 724–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Chao X, Yang L, Lu Q, Li T, Ding WX, et al. (2018). Impaired fasting-induced adaptive lipid droplet biogenesis in liver-specific Atg5-deficient mouse liver is mediated by persistent nuclear factor-like 2 activation. The American Journal of Pathology, 188, 1833–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, & Ding WX (2017). Impaired Rab7 and dynamin2 block fat turnover by autophagy in alcoholic fatty livers. Hepatology Communications, 1, 473–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang S, Ni HM, Huang H, & Ding WX (2014). Autophagy in alcohol-induced multiorgan injury: Mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. BioMed Research International, 2014, 498491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Lee JS, Inn KS, Gack MU, Li Q, Roberts EA, et al. (2008). Beclin1-binding UVRAG targets the class C Vps complex to coordinate autophagosome maturation and endocytic trafficking. Nature Cell Biology, 10, 776–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CW, Zhang H, Li M, Xiong X, Chen X, Chen X, et al. (2013). Pharmacological promotion of autophagy alleviates steatosis and injury in alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver conditions in mice. Journal of Hepatology, 58, 993–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffler AS, Alers S, Dieterle AM, Keppeler H, Franz-Wachtel M, Kundu M, et al. (2011). Ulk1-mediated phosphorylation of AMPK constitutes a negative regulatory feedback loop. Autophagy, 7, 696–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, & Cederbaum AI (2008). CYP2E1 and oxidative liver injury by alcohol. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 44, 723–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, & Cederbaum AI (2015). Autophagy protects against CYP2E1/chronic ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity. Biomolecules, 5, 2659–2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri A, Demeilliers C, Amsellem S, Pessayre D, & Fromenty B (2001). Acute ethanol administration oxidatively damages and depletes mitochondrial dna in mouse liver, brain, heart, and skeletal muscles: Protective effects of antioxidants. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 298, 737–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri A, Gaou I, De Kerguenec C, Amsellem S, Haouzi D, Berson A, et al. (1999). An alcoholic binge causes massive degradation of hepatic mitochondrial DNA in mice. Gastroenterology, 117, 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda N, Sato S, Shiba K, Okatsu K, Saisho K, Gautier CA, et al. (2010). PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. The Journal of Cell Biology, 189, 211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner C, Lorenz H, Weihofen A, Selkoe DJ, & Lemberg MK (2011). The mitochondrial intramembrane protease PARL cleaves human Pink1 to regulate Pink1 trafficking. Journal of Neurochemistry, 117, 856–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N (2010). The role of the Atg1/ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 22, 132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy LE, Ding WX, Cresci G, Saikia P, & Shah VH (2016). Linking pathogenic mechanisms of alcoholic liver disease with clinical phenotypes. Gastroenterology, 150, 1756–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, & Ohsumi Y (2009). Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: Lessons from yeast. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology, 10, 458–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Gautier CA, Shen J, et al. (2010). PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biology, 8, e1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni HM, Bhakta A, Wang S, Li Z, Manley S, Huang H, et al. (2014). Role of hypoxia inducing factor-1beta in alcohol-induced autophagy, steatosis and liver injury in mice. PLoS One, 9, e115849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni HM, Du K, You M, & Ding WX (2013). Critical role of FoxO3a in alcohol-induced autophagy and hepatotoxicity. The American Journal of Pathology, 183, 1815–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni HM, Williams JA, & Ding WX (2015). Mitochondrial dynamics and mitochondrial quality control. Redox Biology, 4, 6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara K, Sekito T, Niimi K, & Ohsumi Y (2008). The Atg18-Atg2 complex is recruited to autophagic membranes via phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and exerts an essential function. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283, 23972–23980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsumi Y (2001). Molecular dissection of autophagy: Two ubiquitin-like systems. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology, 2, 211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papinski D, Schuschnig M, Reiter W, Wilhelm L, Barnes CA, Maiolica A, et al. (2014). Early steps in autophagy depend on direct phosphorylation of Atg9 by the Atg1 kinase. Molecular Cell, 53, 471–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parzych KR, & Klionsky DJ (2014). An overview of autophagy: Morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 20, 460–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polson HE, de Lartigue J, Rigden DJ, Reedijk M, Urbe S, Clague MJ, et al. (2010). Mammalian Atg18 (WIPI2) localizes to omegasome-anchored phagophores and positively regulates LC3 lipidation. Autophagy, 6, 506–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasineni K, Donohue TM Jr., Thomes PG, Yang L, Tuma DJ, McNiven MA, et al. (2017). Ethanol-induced steatosis involves impairment of lipophagy, associated with reduced Dynamin2 activity. Hepatology Communications, 1, 501–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F, Komatsu M, Finley K, & Simonsen A (2012). Selective types of autophagy. International Journal of Cell Biology, 2012, 156272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley NE, Li J, Worrall S, Rothnagel JA, Swagell C, van Leeuwen FW, et al. (2002). The Mallory body as an aggresome: In vitro studies. Experimental and Molecular Pathology, 72, 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell RC, Tian Y, Yuan H, Park HW, Chang YY, Kim J, et al. (2013). ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nature Cell Biology, 15, 741–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott MB, Rasineni K, Weller SG, Schulze RJ, Sletten AC, Casey CA, et al. (2017). Beta-adrenergic induction of lipolysis in hepatocytes is inhibited by ethanol exposure. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 292, 11815–11828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder B, Schulze RJ, Weller SG, Sletten AC, Casey CA, & McNiven MA (2015). The small GTPase Rab7 as a central regulator of hepatocellular lipophagy. Hepatology, 61, 1896–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze RJ, Drizyte K, Casey CA, & McNiven MA (2017). Hepatic lipophagy: New insights into autophagic catabolism of lipid droplets in the liver. Hepatology Communications, 1, 359–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze RJ, Rasineni K, Weller SG, Schott MB, Schroeder B, Casey CA, et al. (2017). Ethanol exposure inhibits hepatocyte lipophagy by inactivating the small guanosine triphosphatase Rab7. Hepatology Communications, 1, 140–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serviddio G, Bellanti F, Sastre J, Vendemiale G, & Altomare E (2010). Targeting mitochondria: A new promising approach for the treatment of liver diseases. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 17, 2325–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setshedi M, Wands JR, & Monte SM (2010). Acetaldehyde adducts in alcoholic liver disease. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 3, 178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Novak I, Komatsu M, et al. (2009). Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature, 458, 1131–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KJ, McCoy MK, Blackinton J, Beilina A, van der Brug M, Sandebring A, et al. (2011). DJ-1 acts in parallel to the PINK1/parkin pathway to control mitochondrial function and autophagy. Human Molecular Genetics, 20, 40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomes PG, Trambly CS, Fox HS, Tuma DJ, & Donohue TM Jr. (2015). Acute and chronic ethanol administration differentially modulate hepatic autophagy and transcription factor EB. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 39, 2354–2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomes PG, Trambly CS, Thiele GM, Duryee MJ, Fox HS, Haorah J, et al. (2012). Proteasome activity and autophagosome content in liver are reciprocally regulated by ethanol treatment. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 417, 262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thumm M, Egner R, Koch B, Schlumpberger M, Straub M, Veenhuis M, et al. (1994). Isolation of autophagocytosis mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Letters, 349, 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada M, & Ohsumi Y (1993). Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Letters, 333, 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto H, Reidelberger RD, French SW, & Largman C (1984). Long-term cannulation model for blood sampling and intragastric infusion in the rat. The American Journal of Physiology, 247, R595–R599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vives-Bauza C, Zhou C, Huang Y, Cui M, de Vries RL, Kim J, et al. (2010). PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107, 378–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Winter D, Ashrafi G, Schlehe J, Wong YL, Selkoe D, et al. (2011). PINK1 and Parkin target Miro for phosphorylation and degradation to arrest mitochondrial motility. Cell, 147, 893–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber JL, & Tooze SA (2010). Coordinated regulation of autophagy by p38alpha MAPK through mAtg9 and p38IP. The EMBO Journal, 29, 27–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner J, Saghir M, Warshaw AL, Lewandrowski KB, Laposata M, Iozzo RV, et al. (2002). Alcoholic pancreatitis in rats: Injury from nonoxidative metabolites of ethanol. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 283, G65–G73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JA, & Ding WX (2015). A mechanistic review of mitophagy and its role in protection against alcoholic liver disease. Biomolecules, 5, 2619–2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JA, & Ding WX (2018). Mechanisms, pathophysiological roles and methods for analyzing mitophagy—Recent insights. Biological Chemistry, 399, 147–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JA, Manley S, & Ding WX (2014). New advances in molecular mechanisms and emerging therapeutic targets in alcoholic liver diseases. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20, 12908–12933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JA, Ni HM, Ding Y, & Ding WX (2015). Parkin regulates mitophagy and mitochondrial function to protect against alcohol-induced liver injury and steatosis in mice. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 309, G324–G340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Bhopale KK, Ansari GA, & Kaphalia BS (2008). Ethanol-induced cytotoxicity in rat pancreatic acinar AR42J cells: Role of fatty acid ethyl esters. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 43, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Cai P, Clemens DL, Jerrells TR, Ansari GA, & Kaphalia BS (2006). Metabolic basis of ethanol-induced cytotoxicity in recombinant HepG2 cells: Role of nonoxidative metabolism. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 216, 238–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Wang X, Zhou R, Yang L, & Cederbaum AI (2012). Alcohol steatosis and cytotoxicity: The role of cytochrome P4502E1 and autophagy. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 53, 1346–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano K, & Youle RJ (2013). PINK1 is degraded through the N-end rule pathway. Autophagy, 9, 1758–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin XM, Ding WX, & Gao W (2008). Autophagy in the liver. Hepatology, 47, 1773–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y-HCC (2018). Liver cirrhosis mortality in the United States: National, state, and regional trends, 2000–2015. Surveillance Report #111. Available at: https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance111/Cirr115.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Zakhari S (2006). Overview: How is alcohol metabolized by the body? Alcohol Research & Health, 29, 245–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatloukal K, French SW, Stumptner C, Strnad P, Harada M, Toivola DM, et al. (2007). From Mallory to Mallory-Denk bodies: What, how and why? Experimental Cell Research, 313, 2033–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelner I, Matlow JN, Natekar A, & Koren G (2013). Synthesis of fatty acid ethyl esters in mammalian tissues after ethanol exposure: A systematic review of the literature. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 45, 277–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further reading

- Kim J, & Guan KL (2011). Regulation of the autophagy initiating kinase ULK1 by nutrients: Roles of mTORC1 and AMPK. Cell Cycle, 10, 1337–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Management of substance abuse, Available at: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/facts/alcohol/en/.