Abstract

Approaches to stereocontrol that invoke thermodynamic control fail when two or more potential products are energetically similar, but rational structural perturbations can be employed to break the energetic degeneracy and provide selective transformations. This manuscript illustrates that tethering is an effective approach for the stereoselective construction of bis-spiroketals with thermodynamically similar stereoisomers, providing a new approach to set remote stereocenters and prepare complex structures that have not previously been accessed stereoselectively.

Keywords: cyclization, diastereoselectivity, macrocycles, oxygen heterocycles, spiro compounds

Graphical Abstract

Mind the gap: This manuscript describes the capacity of tethers to direct stereoselective, thermodynamically controlled syntheses of bis-spiroketals. Remote stereocontrol can be excellent when tethering is coupled with Re2O7-mediated isomerization and dehydrative cyclization. This strategy is applied to the stereocontrolled construction of the spirolide core and to an enantioselective synthesis of the pinnatoxin bis-spiroketal in which the generation of multiple stereocenters is directed by a single stereogenic alcohol.

Utilizing substrate-based thermodynamic control to dictate stereochemical outcomes avoids the complex catalysts or stoichiometric reagents that are required for reagent-controlled approaches. The formation of spiroketals from keto diols is a classic example of this strategy,[1] whereby the doubly anomeric stereoisomer often forms spontaneously. Extending this strategy to the synthesis of bis-spiroketals, such as those found in the marine shellfish toxins pinnatoxin A (1)[2] and spirolide C (2),[3] from diketo diols has not proven to be readily successful. The challenge results from the absence of anomeric stabilization in tetrahydrofuran rings.[4] The elegant syntheses of the pinnatoxin bis-spiroketal,[5] therefore, required substrates with multiple stereocenters and exploited remote hydrogen-bonding and steric effects, while the stereoselective synthesis of the spirolide bis-spiroketal remains an unsolved problem.[6] The construction of these units provides an excellent opportunity to demonstrate the merits of utilizing tethering to provide a thermodynamic bias the stereochemical outcomes of reactions. This manuscript describes the spirotricyclization of macrocyclic diketo diols in which a tether breaks the energetic degeneracy of the product stereoisomers. Coupling this approach with Re2O7-mediated allylic alcohol regio- and steroisomerization provides an enantioselective method for preparing the pinnatoxin bis-spiroketal, whereby numerous remote stereocenters are established with high control.

Employing precursors with stereodefined alcohols leads to the first stereoselective construction of the spirolide bis-spiroketal.

We have been exploring the use of Re2O7 as a catalyst for complexity-generating reactions from allylic alcohol substrates.[7] The spirocycle-forming examples in Scheme 1[7a] are particularly relevant to the objectives in this manuscript. The conversion of diol 3 to spiroketal 4 shows that the stereochemical information in a non-allylic alcohol can control the configuration of a remote stereocenter through thermodynamic control without loss of enantiomeric integrity. Bis-spiroketal formation proceeds smoothly and rapidly, as seen in the formation of 6 and 7 from 5, but the lack of a significant thermodynamic preference results in a 1:1 mixture of products. Examining the structures of the products reveals that the alkenyl groups in 6, which contains the stereochemical orientation present in pinnatoxin A, have a proximal relationship whereas those in 7 have a distal relationship. We postulated that tethering the alkenyl groups with a chain that allows for the formation of the stereochemical orientation in 6 while being too short to permit the alternate diastereomer would provide a unique and effective method for directing the outcomes of these reactions. Precedent from this strategy came from our studies in using tethering to control the stereochemistry of bridged tetrahydropyrans in oxidative Prins cyclizations[8] and from insightful examples showing that that a macrocyclic architecture can influence the relative stabilities of otherwise energetically similar spiroketals.[9]

Scheme 1.

Re2O7-Catalyzed generation of spiroketals and bis-spiroketals.

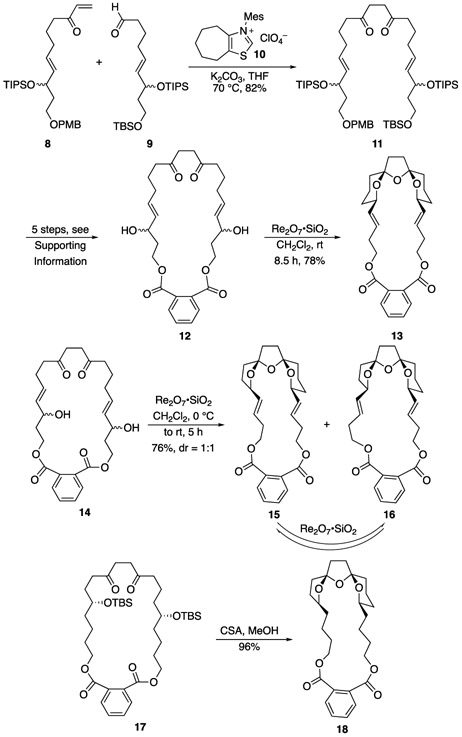

This plan was tested as shown in Scheme 2. The 1,4-diketone substrate is available through an efficient Stetter reaction between enone 8 and aldehyde 9 in the presence of Glorius’ pre-catalyst (10) to yield 11.[10],[11] A sequence of routine protecting group manipulations and acylations provided substrate 12. Proceeding through this sequence with a diastereomeric mixture facilitates the sequence but does not result in handling difficulties because the remote stereocenters result in spectroscopically and chromatographically identical isomers. The phthalate diester linkage was selected for synthetic ease, though numerous other connecting groups could, in principle, be employed. Exposing 12 to Re2O7•SiO2[7b] (5 mol%, selected based on its ease of handling for small scale reactions) initially provided a mixture of diastereomeric products that equilibrated to yield 13 as a single stereoisomer after 8.5 h, thereby demonstrating the ability of the tethering strategy to control the stereochemical orientation of the central tetrahydrofuran in a manner that is relevant to the synthesis of the pinnatoxin core. X-ray diffraction studies of the small crystals of 13 did not deliver a well-resolved structure but provided strong evidence for the stereochemical outcome.[12] The lower homologue 14, prepared through a similar sequence, also undergoes cyclization to form bis-spiroketals 15 and 16 in a 1:1 ratio. The structures of these isomers, which differ in the stereochemical orientations of their peripheral tetrahydrofuran rings, were determined based on extensive 1H and 13C NMR analyses and a crystal structure of 16.[12],[13] The ability to control the stereochemical orientation of the central tetrahydrofuran ring is unprecedented for this ring system.[6] Exposing either 15 or 16 to Re2O7•SiO2 regenerated the 1:1 mixture that was observed in the cyclization, indicating that the product ratio is due to thermodynamic, rather than kinetic, control. This result indicates that tethering will be useful in approaches to the spirolide core that utilize substrates with stereochemically defined alcohols. Indeed, acid-mediated silyl ether cleavage of 17 resulted in a remarkably efficient conversion to 18, delivering a single stereoisomer in 96% yield, demonstrating the first stereocontrolled synthesis of the spirolide bis-spiroketal. This outcome was verified through crystallographic analysis.

Scheme 2.

Tethered bis-spiroketal synthesis. TBS = tert-butyl dimethylsilyl, TIPS = triisopropylsilyl, PMB = para-methoxybenzyl, Mes = mesityl, 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl.

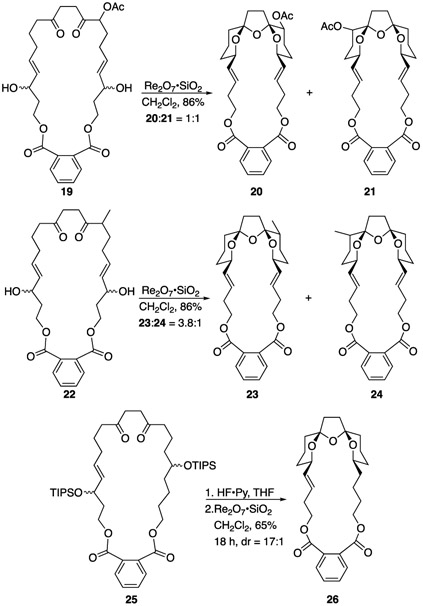

Exploiting the stereochemical equilibration that is inherent in the Re2O7-catalyzed transformations in enantioselective bis-spiroketal construction requires diastereocontrol relative to a non-equilibrating stereocenter (Scheme 3). The stereocenter that is embedded in the tricyclic core of the pinnatoxins became the initial focus of our studies. Acetoxy-substituted macrocycle 19 served as the initial substrate for diastereoselectivity studies since the product could be converted to a ketone that could eventually allow for tertiary alcohol formation. Exposing 19 to Re2O7•SiO2 successfully generated bis-spiroketals 20 and 21 in good yield, but without a stereochemical preference. These isomers could not be interconverted through re-exposure to the reaction conditions because both rings would need to undergo stereomutation, which would require the formation of high energy intermediates. Postulating that increasing the steric bulk of the substituent while minimizing the potential for anchimeric assistance would improve diastereocontrol led to the formation of methyl-containing substrate 22, with the expectation that the resulting methine group could serve as a substrate for stereospecific carbon–hydrogen bond functionalization to form the tertiary alcohol.[14] Spirocyclization indeed proceeded with greater stereocontrol, with 23 and 24 being formed in a 3.8:1 ratio. The orientations of the methyl groups in these compounds were determined through 1-D TOCSY experiments.[12] No effort was made to optimize the stereocontrol since the major isomer had the incorrect stereochemical orientation for stereoretentive oxidative tertiary alcohol formation. The led us to explore a variant of the strategy used for the conversion of 3 to 4 (Scheme 1) whereby the stereochemical information from a non-allylic secondary alcohol is transmitted across the ring system. Thus, 25 was deprotected and the resulting diol smoothly isomerized to bis-spiroketal 26. Equilibration was slow but ultimately led to a 17:1 diastereomeric ratio of products. Attempts to enhance the stereoselectivity further resulted in a lower yield. The two-step sequence was employed based on the difficulty in characterizing the mixture of stereo- and constitutional isomers that result from partial hemiketal formation in the deprotected cyclization substrate.

Scheme 3.

Stereoselectivity relative to a non-equilibrating stereocenter.

These results provided the framework for the enantioselective construction of the bis-spiroketal in the pinnatoxins (Scheme 4). This approach utilizes a dithiane as a precursor to the tertiary alcohol in the ring system, since the use of a ketone in this role could inhibit the generation of the adjacent oxocarbenium ion that is essential for cyclic ketal formation. The route commenced from dihydrofuran (27) through transketalization with propane dithiol[15] followed by oxidation to form aldehyde 28.[16] Coupling with allylic stannane 29[17] under Maruoka’s enantioselective conditions[18] provided 30, with the minor enantiomer being undetectable. This reaction delivers the exocyclic alkene group for the pinnatoxin subunit synthesis, and also generates the stereocenter[19] that will control all other stereocenters in the sequence while providing an efficient fragment coupling. The four-step sequence of silyl ether formation, formylation, and vinylation provided allylic alcohol 31. The corresponding enone is somewhat unstable, so oxidation was delayed until immediately before coupling with the aldehyde. The synthesis of aldehyde 34 was initiated by the hydrozirconation and Me2Zn-mediated transmetallation[20] of alkyne 32 followed by quenching with aldehyde 33. Protection of the resulting secondary alcohol as a TIPS ether, selective TBS ether cleavage, and oxidation formed 34. Oxidation of 31 followed by Stetter coupling with 34 in the presence of 10 provided 1,4-diketone 35 in excellent yield. Cleaving the TBS ether under mildly acidic conditions, acylation with phthalic anhydride, and oxidative PMB ether cleavage generated seco-acid 36 efficiently. Macrocyclization under Shiina’s conditions[21] provided lactone 37.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of the spirotricyclization substrate. a) MeOH, BF3•OEt2, CH2Cl2, then 1,3-propanedithiol, 73%; b) (ClCO)2, DMSO, Et3N, CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 70%; c) 28, TiCl4, Ti(OiPr)4, Ag2O, (R)-BINOL, CH2Cl2, −20 °C, 82%, >99% ee; d) TIPSOTf, 2,6-lutidine, CH2Cl2, 94%; e) nBuLi, THF, −25 °C, then DMF, −78 °C, 83%; f) Vinylmagnesium bromide, THF, −50 °C, 93%; g) Cp2Zr(H)Cl, CH2Cl2, then Me2Zn, then 32, 94%; h) TIPSOTf, 2,6-lutidine, CH2Cl2; i) PPTs, EtOH; j) SO3•Py, Et3N, DMSO, CH2Cl2, 78% (three steps); k) Dess-Martin periodinane, NaHCO3, CH2Cl2; l) 9, 10, K2CO3, THF, 70 °C, 91% (two steps); m) PPTs, EtOH; n) Phthalic anhydride, DMAP, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 90% (two steps); o) DDQ, CH2Cl2, H2O. p) MNBA, DMAP, CH2Cl2, 85%, two steps. PPTs = pyridinium para-toluenesulfonate, DDQ = 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone, MNBA = 2-methyl-6-nitro-benzoic anhydride, DMAP = 4-dimethylaminopyridine.

Spirocycle formation proceeded through deprotection of the silyl ethers of 37 (92% yield) followed by the addition of addition of Re2O7•SiO2 to the resulting isomeric mixture (Scheme 5). Tricyclic product was formed very quickly, presumably due to the conformational biasing by the dithiane. Equilibration was quite sluggish for this reaction, however, so we added hexafluoroisopropyl alcohol (HFIP) to the reaction upon the completion of the tricyclic unit based on our previous observation that HFIP is compatible with Re2O7 and facilitates ionization reactions.[22] Ultimately this resulted in the isolation of 38 in 81% yield as a 7.5:1 mixture of separable diastereomers. The minor diastereomer in this reaction places the alkenyl group in an axial orientation and this isomer undergoes equilibration under the reaction conditions to form the same 7.5:1 ratio of diastereomers. This verifies that the process is under thermodynamic control, with the increased complexity resulting in a minor erosion in diastereocontrol. Thus the tethering and isomerization strategy delivered the tricyclic unit efficiently and with high diastereocontrol. Cleaving the dithiane through alkylative conditions followed by the addition of MeMgI delivered the tertiary alcohol as a single diastereomer. The stereochemical outcome of this reaction was determined through a NOESY experiment and from the observation of a 0.6 Hz coupling constant for the axial methyl group in the 1H NMR spectrum, consistent with the known W-coupling of axially-oriented methyl groups adjacent to a carbon with an axially oriented hydrogen.[23] This is consistent with previous related examples.[5b],[6a,b] The phthalate diester was cleaved under standard conditions to deliver 39 in good yield. Thus the pinnatoxin bis-spiroketal was delivered with excellent stereocontrol form a sequence in which a single, stereochemically defined alcohol guided the generation of all subsequent stereogenic units.

Scheme 5.

Completion of the pinnatoxin bis-spiroketal unit synthesis. a) Bu4NF, AcOH, THF, 92%; b) Re2O7•SiO2, CH2Cl2, then HFIP, 7 h, 81%, dr = 7.5:1; c) MeI, Ag2CO3, H2O, CH3CN; d) MeMgI, Et2O, −78 °C, 52% (two steps); e) LiOH•H2O, THF, H2O, 80%.

We have described a strategy for controlling the stereochemical outcome of reactions that generate bis-spiroketals. This approach merges the use of Re2O7 as a catalyst to promote cyclization and thermodynamically controlled stereochemical equilibration with the incorporation of a tether to create an energetic bias for a specific stereoisomer. The method was applied to the synthesis of the pinnatoxin core, in which a single stereocenter directed the generation of three rings and three new stereocenters with a high degree of control. The tethering strategy also proved to be extremely effective in the preparation of the challenging spirolide bis-spiroketal. Applying this method to molecules of the complexity of the bis-spiroketals demonstrates a high degree of functional group compatibility that has also been observed in other applications of oxorhenium catalysts in natural product synthesis, whereby reactions proceed in the presence of essentially all non-basic moieties.[24] The phthalate diester linker allowed for the demonstration of concept. However the natural products that contain bis-spiroketals often embed these units in a macrocycle, indicating that the strategy will be applicable to natural product syntheses at a very late stage in the sequence. Notably a proposal for the biosynthesis of spirolide[25] postulates that the bis-spiroketal forms after the macrocycle is formed, indicating that the tethering strategy mimics nature’s approach to the formation of these structures.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Examples of natural products with the bis-spiroketal motif.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institutes of Health (R01GM103886) for generous support of this work. We thank Mr. Qi Qin for useful discussions regarding the design of non-routine NMR experiments for challenging structure determinations, and Dr. Steve Geib and Dr. Edison Castro (Hernández Sánchez group) for conducting the crystallographic studies.

References

- [1] a).Palmes JA, Aponick A, Synthesis 2012, 44, 3699–3721 [Google Scholar]; b) Raju BR, Saikia AK, Molecules 2008, 13, 1942–2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Aho JE, Pihko PM, Rissa TK, Chem. Rev 2005, 105, 4406–4440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mead KT, Brewer BN, Curr. Org. Chem 2003, 7, 227–256. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Uemura D, Chou T, Haino T, Nagatsu A, Fukuzawa S, Zheng S.-z., Chen H.-s., J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117, 1155–1156. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hu T, Burton IW, Cembella AD, Curtis JM, Quilliam MA, Walter JA, Wright JLC, J. Nat. Prod 2001, 64, 308–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ellervik U, Magnusson G, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 2340–2347. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pinnatoxin approaches: a) McCauley JA, Nagasawa K, Lander PA, Mischke SG, Semones MA, Kishi Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 7647–7648 [Google Scholar]; b) Sakamoto S, Sakazaki H, Hagiwara K, Kamada K, Ishii K, Noda T, Inoue M, Hirama M, Angew. Chem 2004, 116, 6667–6672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2004, 43,6505–6510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Nakamura S, Kititchi F, Hashimoto S, Angew. Chem 2008, 120, 7199–7202 [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 7091–7094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Stivala CE, Zakarian A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130,3774–3776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Araoz R, Servent D, Molgo J, Iorga BI, Fruchart-Gaillard C, Benoit E, Gu Z, Stivala C, Zakarian A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 10499–10511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Yasukawa Y, Tsuchikawa H, Todokoro Y, Murata M, Asian J. Org. Chem 2018, 7, 1101–1106 [Google Scholar]

- [6].Spirolide approaches: a) Brimble MA, Furkert DP, Org. Biomol. Chem 2004, 2, 3573–3583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ishihara J, Ishizaka T, Suzuki T, Hatakeyama S, Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 7855–7858 [Google Scholar]; c) Volchkov I, Sharma K, Cho EJ, Lee D, Chem. Asian J 2011, 6, 1961–1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Labarre-Lainé J, Periñan I, Desvergnes V, Landais Y, Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20, 9336–9341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7] a).Xie Y, Floreancig PE, Chem. Sci 2011, 2, 2423–2427 [Google Scholar]; b) Xie Y, Floreancig PE, Angew. Chem 2013, 125, 653–656 [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 625–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Xie Y, Floreancig PE, Angew. Chem 2014, 126, 5026–5029 [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 4926–4929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Afeke C, Xie Y, Floreancig PE, Org. Lett 2019, 21, 5064–5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Han X, Floreancig PE, Org. Lett 2012, 14, 3808–3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9] a).Marjanovic J, Kozmin SA, Angew. Chem 2007, 119, 9010–9013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2007, 46, 8854–8857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fujiwara K, Suzuki Y, Koseki N, Aki Y.-i., Murata S.-i., Yamamoto F, Kawamura M, Norikura T, Matsue H, Murai A, Katoono R, Kawai H, Suzuki T, Angew. Chem 2014, 126, 799–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 780–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Biju AT, Wurz NE, Glorius F, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 5970–5971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See also: Guo B, PhD thesis, University of Pittsburgh (USA), 2012, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- [11].For a related 1,4-diketone synthesis with a sila-Stetter reaction, see: Labarre-Lainé J, Beniazza R, Desvergnes V, Landais Y, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 4706–4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Please see the Supporting Information for details.

- [13].CCDC 1979474 (16) and 1979473 (18) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- [14] a).Chen MS, White MC, Science 2007, 318, 783–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Litvinas ND, Brodsky BH, Du Bois J, Angew. Chem 2009, 121, 4583–4586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 4513–4516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Solladié G, Fernandez I, Maestro C, Tetrahedron Asymmetry 1991, 2, 801–819. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bournaud C, Marchal E, Quintard A, Sulzer-Mossé S, Alexakis A, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2010, 21, 1666–1673 [Google Scholar]

- [17] a).Trost BM, King SA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112, 408–422 [Google Scholar]; b) Williams DR, Kiryanov AA, Emde U, Clark MP, Berliner MA, Reeves JT, Angew. Chem 2003, 115, 1296–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2003, 42, 1258–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hanawa H, Hashimoto T, Maruoka K, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 1708–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].The enantiomeric excess and absolute stereochemical orientation of this alcohol were determined through Mosher ester analysis. a) Dale JA, Dull DL, Mosher HS, J. Org. Chem 1969, 34, 2543–2549 [Google Scholar]; b) Hoye TR, Jeffrey CS, Shao F, Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 2451–2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wipf P, Xu W, Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 5197–5200. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shiina I, Kubota M, Ibuka R, Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 7535. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Qin Q, Xie Y, Floreancig PE, Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 8528–8534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Williamson KL, Howell T, Spencer TA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1966, 88, 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- [24] a).Rohrs TM, Q Q, Floreancig PE, Angew. Chem 2017, 129, 11040–11044; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 10900–10904 [Google Scholar]; b) Trost BM, Amans D, Seganish WM, Chung CK, Chem. Eur. J 2012, 18, 2961–2971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jung HH, Seiders JR II, Floreancig PE, Angew. Chem 2007, 119, 8616–8619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2007, 46, 8464–8467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Hutchison JM, Lindsay HA, Dormi SS, Jones GD, Vivic DA, McIntosh MC, Org. Lett 2006, 8, 3663–3665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Trost BM, Toste FD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 11262–11263. [Google Scholar]

- [25].MacKinnon SL, Cembella AD, Burton IW, Lewis N, LeBlanc P, Walter JA, J. Org. Chem 2006, 71, 8724–8731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.