Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this review is to systematically review randomized controlled trials on lifestyle interventions on PCa patients undergoing androgen deprivation therapy.

Methods

A literature search was conducted using the electronic databases Medline and PubMed. To be eligible, studies had to be randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that focused on side effects of ADT and lifestyle interventions to reduce side effects for men undergoing ADT with PCa. Lifestyle interventions were defined as interventions that included any dietary or behavioral components.

Results

Twenty-nine trials were included. Most of them focused on exercise interventions, while some investigated the effect of dietary or behavioral interventions. The effect of different lifestyle influencing modalities aimed to improve on the adverse effects of ADT varied greatly.

Conclusions

It is not possible to draw one conclusion on the effect of exercise-based interventions, but noted on several adverse effects of ADT improvement. Further studies are necessary to develop personalized lifestyle interventions in order to mitigate the adverse effects.

Keywords: Males, ADT, Side effects, Prostate cancer, Lifestyle interventions

Introduction

Prostate cancer is one of the most common forms of cancer in men and the second cause of death [1]. Androgens and androgen receptor signaling play an important role in the normal growth and function of the prostate, but also in the development and maintenance of prostate cancer. The beneficial effect of castration in the treatment of prostate cancer has already been discovered in 1941, by Huggins [2]. LHRH agonists are the most chosen form of chemical castration [3]. LHRH agonists bring the serum testosterone to a level similar to castration by interfering in the pulsatile release of LHRH in the hypothalamus, thereby down-regulating the release of luteinizing hormone in the anterior pituitary gland. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) achieves a remission in 80–90% in men with advanced prostate cancer and an average progression-free interval of 12–33 months [4].

Despite the fact that this form of therapy is very successful, it also known for its side effects and the impact of these side effects on the quality of life in addition to the psychological and physical effects influencing the quality of life in the long term. The most common life quality diminishing side effects are reduced libido, depression, fatigue, gynecomastia, hot flushes, obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, and osteoporosis [5].

Non-pharmaceutical lifestyle interventions aimed to reduce side effects while aiming to leave control in the hands of the patient are very important. They may prevent medicalization and are thought to increase quality of life.

Previous reviews have shown that physical activity may alleviate side effects of ADT [6, 7]. These reviews mainly focused on the effects of different types of exercise, but did not include all types of lifestyle interventions. The aim of this research is to provide a comprehensive overview of recent physical and psychological lifestyle interventions to reduce different side effects of ADT and to investigate the impact of these interventions on quality of life.

Methods

Data acquisition and search strategy

A literature search was conducted using the electronic databases Medline and PubMed. The literature search included relevant publications until January 25, 2019. Predefined search terms were used to identify articles concerning interventions to reduce side effects of ADT used as a therapy for prostate cancer.

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible, the study population had to consist of patients diagnosed with local or advanced PCa in whom ADT was started. Studies had to be randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that focused on side effects of ADT and lifestyle interventions to reduce those side effects. For this review, we selected studies concerning the following psychological effects: quality of life (health-related quality of life and disease-specific quality of life), fatigue, reduced libido, and depression. We selected studies investigating the following physical side effects: gynecomastia, hot flushes, osteoporosis, obesity, or a decreased cardiovascular health. Lifestyle interventions were defined as interventions that included any dietary or behavioral components. Studies reporting on medical therapies to diminish side effects were excluded, as were studies in which the participants stopped their ADT and studies not related to humans.

Screening of abstracts and full-text articles

A search was performed for abstracts that may be used for inclusion. Abstract screening was done according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full-text original articles were retrieved from the selected abstracts; only articles published in English or Dutch that were available for review were selected. Abstracts and original articles were independently assessed by two reviewers for eligibility (MG and NP). Disagreements were solved by consensus procedure in which an independent third author (HBLG) was conducted.

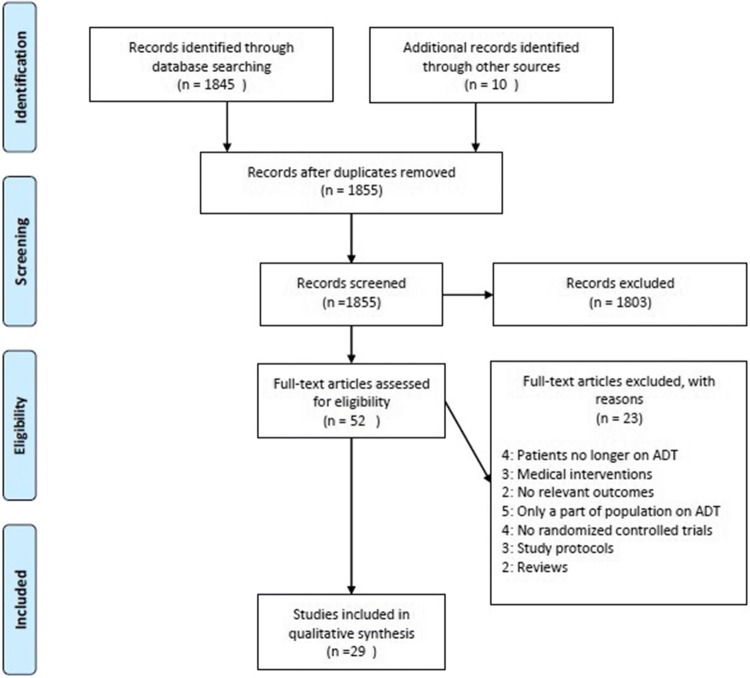

Subsequently, reference lists of all full-text articles were screened to identify additional relevant articles not found in the PubMed and Medline databases. The final number of included and excluded studies is illustrated in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the search and selection process

Study quality assessment tool

The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool was used to assess the risk of bias in the randomized controlled trial [8]. Two reviewers (MG and NP) assessed the overall quality. If no agreement could be reached, an independent person was involved (HPB).

Data synthesis

The following data were independently extracted from full-text articles by two reviewers: study year, study design, study population, mean age, type of interventions, duration and frequency of interventions, relevant study outcomes, and methods to assess these outcomes.

Results

Search results and analysis

Our literature search identified 1961 of which 29 articles were included in this analysis. The studies were all RCTs investigating the effect of life style interventions to mitigate ADT-induced side effects. Twenty studies investigated exercise modalities, two studies investigated dietary advice, and four studies combined these methods. Three studies investigated behavioral components, existing of cognitive behavioral therapy, educational support programs, or self-education. Study characteristics are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of the included studies

| Study year | Patients (n) | Age (mean) | Inclusion criteria | Interventions | Duration intervention (weeks) + frequency (x/week) | Relevant outcomes | Methods to assess relevant outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segal [9] |

Int: 82 Con: 73 Total: 155 |

Int: 68.2 Con: 67.7 |

Local and advanced PCa receiving ADT ≥ 3 months |

Supervised resistance exercise |

Duration: 12 Frequency: 3 |

Fatigue Overweight Quality of life |

FACT-F BMI, waist circumference, skinfolds thickness FACT-P |

| Taylor [10] |

Life: 46 Educ: 51 Con: 37 Total: 134 |

Int + Con: 69.2 | PCa treated with ADT |

Lifestyle activity program Educational support program |

Duration 24 Frequency: week 1–16: 1 4 week: 2 |

Overweight Depression Quality of life |

BMI: Waist and hip circumferences, waist-hip ratio CES-D SF-36, STAI |

| Sharma [11] |

Soy: 20 Con: 19 Total 39 |

Soy: 69.2 Con: 69.0 |

PCa treated with ADT | Soy protein: 20 g |

Duration: 12 Frequency: 7 |

Fatigue Libido and sexual function Hot flushes Quality of life |

SF-36 IIEF, WSFS Blatt-Kupperman scale SF-36 |

| Culos-Reed [12] |

Int: 53 Con: 47 Total: 100 |

Int: 67.2 Con: 68 |

PCa localized or metastatic and expect to receive ADT for ≥ 6 months | Supervised and unsupervised aerobic + resistant exercise |

Duration: 16 Frequency: 3–5 |

Fatigue Overweight Cardiovascular Libido Depression Quality of life |

FSS BMI, waist-to-hip ratio RR EPIC CES-D EORTC-QLQ-C30, EPIC |

| Galvao [13] |

Int: 29 Con: 28 Total: 57 |

Int: 69.5 Con: 70.1 |

Locally or advanced PCa (without bone metastasis) with prior exposure ADT > 2 months | Supervised aerobic + resistance exercise |

Duration: 12 Frequency: 2 |

Fatigue Overweight Cardiovascular Insulin resistance Quality of life |

QLQ-C30, SF-36 Dual X-ray absorptiometry: total lean body mass, regional lean mass: upper limb, lower limb, appendicular skeletal muscle total fat mass, trunk fat mass, and percentage body fat, Blood samples: total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, CRP 400 m walk Blood samples: Insulin + glucose EORTC-QLQ-C30; SF-36 |

| Bourke [14] |

Int: 25 Con: 25 Total: 50 |

Int: 71.3 Con: 72.2 |

Non localized PCa who receiving ADT ≥ 6 months | Supervised + unsupervised aerobic + resistance exercise |

Duration: 12 Frequency: Resistance + aerobic: week 1–6: 1; 7–12:2x Eating seminars: 1x |

Fatigue Overweight Insulin resistance Quality of life |

FACT-F BMI; weight; waist-to-hip ratio Blood biomarkers: insulin; IGF-1 FACT-P; FACT-G |

| Cormie [15] |

Int: 29 Con: 28 Total: 57 |

Int: 69.5 Con: 70.1 |

Locally PCa, on ADT ≥ 2 months and remained hypogonadal for ≥ 6 months | Supervised aerobic + resistance exercise |

Duration: 12 Frequency: 2 |

Libido and sexual function Quality of life |

QLQ-PR25 SF-36 |

| Hvid [16] |

Int: 10 Con: 9 Total: 19 |

Int: 67.8 Con: 68.5 |

PCa with ADT > 3 months Control group: healthy males |

Supervised endurance Exercise |

Duration: 12 Frequency: 3 |

Overweight Cardiovascular Insulin resistance |

Dual x-ray absorptiometry: body lean mass, fat mass, trunk fat mass MR: femoral to liver distance, visceral fat mass, skin fat mass, intermuscular adipose tissue Tissue samples: m. vastus lateralis Blood biomarkers: total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides VO2 Max OGTT Euglycemic–hyperinsulinemic clamp Blood samples: glucose, insulin Glucose kinetics calculations |

| Santa Mina [17] |

Aer: 32 Res: 34 Total: 66 |

Aer: 72.1 Res: 70.6 |

PCa currently receiving ADT ≥ 12 months |

Supervised and unsupervised aerobic or resistance exercise |

Duration: 26 Frequency Total: 3–5 Supervised: 1 × 2 week |

Fatigue Overweight Gynecomastia Cardiovascular Quality of life |

FACT-F BMI, Body fat, waist circumference, body fat: Skinfolds: chest, abdomen + thigh Chest skinfold thickness VO2 max FACT-P; PORPUS |

| Vitolins [18] |

Soy: 30 Ven: 30 V + S: 30 Con: 30 Total:120 |

Soy: 71 Ven: 67 V + S: 69 Con: 67 |

Locally advanced or metastatic PCa on ADT and having hot flushes |

Soy protein: 20 g Venlafaxine |

Duration: 12 Frequency: daily |

Hot flashes Quality of life |

HFSSS FACT-P; FACT-G |

| Walker [19] |

Int: 20 Con: 20 Total: 40 |

NR | PCa on ADT |

Education booklet on side effects Educational review survey |

NA | Libido |

PAIR inventory: DAS scale Sexual activity |

| Bourke [20] |

Int: 50 Con: 50 Total: 100 |

Int: 71 Con: 71 |

Locally advanced or metastatic PCa, previously on ADT ≥ 6 months and planned long term on ADT |

Aerobic + resistance Exercise + dietary advice |

Duration: 12 Frequency Resistance: week 1–6: 2x; 7–12: 1x Aerobic: week 1-6: 1; 7–12: 2x Dietary: 1 × 2 weeks |

Fatigue Overweight Cardiovascular Quality of life |

FACT-F BMI; weight Systolic blood pressure, aerobic exercise tolerance FACT-P |

| Uth [21] |

Int: 29 Con: 28 Total: 57 |

Int: 67.1 Con: 66.5 |

Advanced or locally advanced PCa with ADT or surgical castration ≥ 6 months | Supervised football training |

Duration: 12 Frequency: week 1–8: 2 week 9–12: 3 |

Overweight Cardiovascular |

Dual X-ray absorptiometry: lean body mass, android, gynoid total body fat mass: BMI; waist circumference; hip circumference VO2 max: 4-min walking test; incremental test to exhaustion Pulmonary gas exchange measurements Heart rate monitors |

| Winters- stone [22, 23] |

Int: 29 Con: 22 Total: 51 |

Int: 69.9 Con: 70.5 |

Localized or metastatic PCa currently receiving ADT |

Int: Supervised + unsupervised resistance exercise Cont: Stretching |

Duration: 52 Frequency: 3 |

Fatigue Overweight Insulin resistance Quality of life |

SCFS BMI Dual X-ray absorptiometry: Fat mass; Bone-free lean mass; trunk fat mass Blood biomarkers: insulin; IGF-1 LLFDI |

| Cormie [24] |

Int: 32 Con: 31 Total: 63 |

Int: 69.6 Con: 67.1 |

PCa within first 10 days on ADT and anticipated to remain on ADT ≥ 3 months | Supervised aerobic + resistance exercise |

Duration: 12 Frequency: 2 |

Fatigue Overweight Cardiovascular Osteoporosis Libido Insulin resistance Depression Quality of life |

FACIT-fatigue Dual X-ray absorptiometry: body lean mass, fat mass, appendicular lean mass, trunk fat mass, visceral fat mass Blood biomarkers: CRP VO2 max: 400-m walk test RR: brachial Dual X-ray absorptiometry: BMD: hip, lumbar spine, whole body Blood biomarkers: alkaline phosphatase, P1NP, N-telopeptide, N-telopeptide/creatinine ratio, vitamin D QLQ-PR25 Blood biomarkers: Insulin, glucose BSI-18 QLQ-PR25; SF-36 |

| Nilsen [25] |

Int: 28 Con: 30 Total: 58 |

Int: 66 Con: 66 |

Locally advanced PCa receiving RT after neo-adjuvant ADT for 6 months and adjuvant ADT 9–36 months | Supervised resistance exercise |

Duration: 16 Frequency: 3 |

Overweight Fatigue Osteoporosis Cardiovascular Quality of life |

Dual x-ray absorptiometry: lean body mass, Regional LBM: (trunk, lower extremities, upper extremities, appendicular skeletal mass), fat mass, fat percentage, body mass, BMI EORTC- QLQ-C30 Dual X-ray absorptiometry: BMD: total, total lumbar spine, hip, trochanter and femoral neck Shuttle walk test EORTC-QLQ-C30 |

| O’neill [26] |

Int: 47 Con: 47 Total: 94 |

Int: 69.7 Con: 69.9 |

PCa treated ADT for ≥ 6 months and planned to continue for ≥ 6 months or commencing to start ≥ 6 months | Aerobic exercise + dietary advice |

Duration: 26 Frequency: Walking: 5 |

Overweight Fatigue Cardiovascular Quality of life |

Weight, BMI, fat mass, lean muscle mass, waist-to-hip ratio, mid-upper arm muscle area Fat mass: Skinfold thickness FSS 400-m walk test FACT-P; PSS |

| Stefanopoul ou [27] |

Int: 33 Con: 35 Tot: 68 |

Int: 68.0 Con: 68.7 |

Localized or metastatic PCa undergoing ADT |

CBT booklet | Duration: 4 |

Hot Flushes Depression Quality of life |

HFNS HADS EORTC-QLQ-C30; EORTC- QLQ-PR25 |

| Gilbert [28] |

Int: 25 Con: 25 Total: 50 |

Int: 70.1 Con: 70.4 |

PCa receiving ADT ≥ 6 months + radiotherapy |

Supervised + unsupervised aerobic, balance, resistance exercise + Dietary advice: healthy-eating seminars |

Duration 12 Frequency: Training: 3 Diet: 1 × 2 week |

Overweight Cardiovascular |

BMI, weight Blood biomarkers: total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides RR: Brachial artery FMD, GTN-arterial dilatation VO2 max: Exercise tolerance: walking test |

| Nilsen [29] |

Int: 16 Con: 15 Total: 31 |

Int: 66 Con: 65 |

Locally advanced PCa receiving RT after neo-adjuvant ADT for 6 months and adjuvant ADT 9-36 months | Supervised resistance exercise |

Duration: 16 Frequency: 3 |

Overweight | Muscles biopsies m. Vastus lateralis: protein concentrations, HSP70, Alpha B-crystalline, HSP27, HSP27, HSP60, C OXIV, Citrate synthase Ubiquitin |

| Nilsen [30] |

Int: 12 Con: 11 Total: 23 |

Int: 67 Con: 64 |

Locally advanced PCa receiving RT after neo-adjuvant ADT for 6 months and adjuvant ADT 9–36 months | Supervised resistance exercise |

Duration: 16 Frequency: 3 |

Overweight | Muscle biopsies m. Vastus lateralis: histology, muscle fiber CSA, myonuclei, satellite cells, protein concentrations |

| Sajid [31] |

EXCAP: 6 Wii-fit: 8 Con: 5 Total: 19 |

EXCAP: 75.7 Wii-fit 77.5 Con: 71.8 |

PCa with ADT, ADT combined with RT |

EXCAP: Unsupervised aerobic exercise + resistance exercise Wii-fit: Multi- component exercise on WII |

Duration: 6 Frequency: 5 |

Fatigue Overweight |

SPPB Dual X-ray absorptiometry: body fat mass, body lean mass, skeletal muscle mass |

| Uth [32] |

Int: 29 Con: 28 Total: 57 |

Int: 67.1 Con: 66.5 |

Locally advanced or metastatic PCa undergoing ADT for ≥ 6 months | Supervised football exercise |

Duration: 32 Frequency: week 1–: 2 week 9–12: 3 week 12–32: 2 |

Overweight Osteoporosis |

Dual X-ray absorptiometry: body lean mass, fat mass, percentage fat mass, Dual x-ray absorptiometry: BMD: total hip, femoral, lumbar spine, Blood samples: P1NP, osteocalcin, CTX |

| Uth [33] |

Int: 29 Con: 28 Total: 57 |

Int: 67.1 Con: 66.5 |

Locally advanced or metastatic Pca undergoing ADT for ≥ 6 months |

Supervised football exercise |

Duration: 12 Frequency: wk 1-8: 2 wk 9-12: 3 |

Osteoporosis |

Dual X-ray absorptiometry BMC: total body, legs BMD: total body, legs Blood biomarkers: CTX, P1NP, osteocalcin |

| Kim [34] |

Int: 26 Con: 25 Total: 51 |

Int: 70.5 Con: 71.0 |

PCa Stage I to III receiving ADT |

Unsupervised strength training + resistance exercise |

Duration: 26 Frequency: 3-5 |

Osteoporosis Quality of life |

Dual x-ray absorptiometry: total BMD, regional BMD: Total hip, femur neck, lumbar spine, Blood samples: bs-ALP, Ntx FACT-P |

| Taaffe [35] |

ILRT: 58 ART: 54 Con: 51 Total:163 |

ILRT:68. 9 ART: 69 Con: 68.4 |

PCa with ADT exposure ≥ 2 months, anticipated to receive ADT following 12 months |

Supervised impact + resistance exercise (ILRT) Supervised + unsupervised aerobic + resistance exercise (ART) |

Duration: 52 Frequency: ILRT + AER: 2 | Fatigue Cardiovascular |

EORTC-QLQ-C30; SF-36 400 m walk |

| Wall et al. [36] |

Int: 50 Con: 47 Total: 97 |

Int: 69.1 Con: 69.1 |

Localized PCa on ADT for ≥ 2 months | Supervised and unsupervised aerobic + resistance exercise |

Duration: 26 Frequency: 2 |

Overweight Cardiovascular Insulin resistance |

Dual X-ray absorptiometry: lean body mass, fat mass, trunk fat mass, percentage body fat, appendicular fat mass, weight Blood biomarkers: CRP Respiratory gas analysis: fat oxidation, carbohydrate oxidation Blood samples: LDL; HDL; cholesterol, triglycerides VO2Max; RR: brachial Applanation tonometry: arterial stiffness, aortal blood pressure Carotid-to-radial pulse-wave Blood biomarkers: Insulin: Hba1c, glucose |

| Dawson [37] |

Int: 13 Con: 19 Total: 32 |

Pro: 68.6 Con: 66.3 |

PCa with ADT | Supervised resistance training |

Duration: 12 Frequency: 3 |

Fatigue Overweight Cardiovascular Insulin resistance Depression Quality of life |

BFI Dual X-ray: appendicular skeletal mass, lean body mass, fat mass, percentage body fat, waist circumference Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure Blood biomarkers: Glucose CES-D FACT-G; FACT-P |

RCTs randomized controlled trials; Int intervention group, Con control group, PCa prostate cancer, ADT androgen deprivation therapy, RT radiotherapy, Ven/V venlafaxine, Soy/S soy protein, physical examinations, BMI body mass index, LBM lean body mass, BMD bone mineral density, BMC bone mineral content, PPB positive pressure, breathing, RR blood pressure, OGTT oral glucose tolerance test, VO2 max maximal oxygen consumption, FMD flow-mediated dilatation, GTN-arterial dilatation glyceryl trinitrate-arterial dilatation

Blood biomarkers IGF-1: Insulin Growth Factor-1, IGFBP: Insulin-Like Growth Factor-Binding Peptide, IGFBP-1: Insulin-Like Growth Factor-Binding Peptide-1, IGFBP-3: Insulin-Like Growth Factor-Binding Peptide-3, Hba1c: Glycosylated Hemoglobin type A1c, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, HDL: High Density Lipoprotein, CRP: C-Reactive Protein, CTX: Cyclophosphamide, P1NP: Procollagen Type 1, bs-ALP: bone-specific Alkaline Phosphatase, NTX: N-Telopeptide of type I collagen

Questionnaires CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale, HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, DAS scale: Depression, Anxiety and Stress scale, BFI: Big Five Inventory, BSI-18: Brief Symptom Inventory 18, FSS: Fatigue Severity Scale, FACT-P: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate; FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy General; FACT-F: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Fatigue POMS: Profile Of Mood Status; EIFI-exhaustion: The Exercise-Induced Feeling Inventory EORTC-QLQ-C30: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30, EORTC-QLQ-PR25: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Prostate-Specific 25-item, SF-36: short-form health survey (36), EPIC: Expanded Prostate Cancer Index, HFSS: Hot Flashes Severity Score, HFNS: Hot Flushes and Night Sweats, HFSSS: Hot Flushes Severity Symptom Score, PAIR inventory: Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships, SPPB: Short Physical Performance Battery, IIEF: International Index of Erectile Function, WSFS: Watts Sexual Functioning Scale; PORPUS: Patient-Oriented Prostate Utility Scale, PSS: Perceived Stress Scale, LLFDI: Late Life Function and Disability Instrument, STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

Table 2 shows an overview of RCTs testing mitigation strategies for ADT-induced side effects, categorized per side effect. Table 3 summarizes the quality scores of the RCTs. The quality differed between the studies. The most common source of methodological bias was a lack of proper blinding procedures. Almost one-third of the studies presented incomplete outcome data.

Table 2.

Overview of RCTs testing mitigation strategies for ADT categorized per side effect

| Side effect | Intervention | Study | Outcomes | Methods to measure outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | Aerobic training | Santa Mina et al. [17] | No difference | PRO (FACT-P; PORPUS) |

| Aerobic training + dietary advice | O’neill et al. [26] | Improvement in the individual functional well-being subscale (P = 0.04) measured with FACT-P at 26 weeks | PRO (FACT-P; PSS) | |

| Aerobic + Resistance training | Culos-Reed et al. [12] | No difference | PRO (EORTC-QLQ-C30, EPIC) | |

| Galvao et al. [13] | Significant improvement for general health (P = 0.022), vitality (P = 0.19) and physical health score (P = 0.02) measured with SF-36 Significant improvement in role (P < 0.001), cognitive (P = 0.007), nausea (P = 0.025), dyspnea (P = 0.17) measured with QLQ-C30 after 12 weeks | PRO (QLQ-C30; SF-36) | ||

| Bourke et al. [14] | No difference | PRO (FACT-P; FACT-G) | ||

| Cormie et al. [24] | Significant improvement in social functioning (P = 0.015), mental health domains (P = 0.006) and the mental health composite score (P = 0.022) after 12 weeks measured with SF-36 | PRO (QLQ-PR25; SF-36) | ||

| Aerobic + resistance + dietary advice | Cormie et al. [15] | Significant difference in perceived general health (P = 0.022), vitality (P = 0.019); physical health composite (P = 0.02) subscales measured with SF-36 at 12 weeks | PRO (SF-36) | |

| Bourke et al. [20] | Significant improvement after 12 weeks (P = 0.001), no change after 24 weeks measured with FACT-P | PRO (FACT-P) | ||

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | Stefanopoulou et al. [27] | No differences | PRO (EORTC-QLQ-C30; EORTC-QLQ-PR25) | |

| Resistance training | Segal et al. [9] | Increase in QOL, compared with a decrease for the control group (P = 0.001) measured with FACT-P after 12 weeks | PRO (FACT-P) | |

| Taylor et al. [5] | No differences | PRO (SF-36, STAI) | ||

| Santa Mina et al. [17] | No differences | PRO (FACT-P; PORPUS) | ||

| Nilsen et al. [25] | No differences | PRO (EORTC-QLQ-C30) | ||

| Kim et al. [34] | No differences | PRO (FACT-P) | ||

| Dawson et al. [37] | Significant improvement in quality of life measured with FACT-G (P = 0.048) and FACT-P (P = 0.04) | PRO (FACT-G; FACT-P) | ||

| Soy protein | Sharma et al. [11] | No differences | PRO (SF-36) | |

| Vitolins et al. [18] | Improvements in emotional (P = 0.029) and functional subscales (P = 0.041) and in FACT-G (P = 0.025) and FACT-P total scores. (P = 0.048) | PRO (FACT-P; FACT-G) | ||

| Depression | Aerobic + resistance training | Culos-Reed et al. [12] | No differences | PRO (CES-D) |

| Santa Mina et al. [17] | No differences | PRO (FACT-F) | ||

| Cormie et al. [24] | No differences | PRO (BSI-18) | ||

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | Stefanopoulou et al. [27] | No differences | PRO (HADS) | |

| Educational support program | Taylor et al. [10] | No differences | PRO (CES-D) | |

| Lifestyle activity program | Taylor et al. [10] | No differences | PRO (CES-D) | |

| Resistance training | Dawson et al. [37] | No differences | PRO (CES-D) | |

| Fatigue | Aerobic training | Santa Mina et al. [17] | No differences | PRO (FACT-F) |

| Aerobic training + dietary advice | O’neill et al. [26] | No differences | PRO (FSS) | |

| Aerobic + resistance training | Cormie et al. [24] | Significant reduction (P = 0.042) measured with FACIT-fatigue | PRO (FACIT-fatigue) | |

| Culos-Reed et al. [12] | No difference | PRO (FSS) | ||

| Galvao et al. [13] | Significant reduction in fatigue (P = 0.021) and increased vitality (P = 0.019) measured with SF-36 and QLQ-C30 resp. | PRO (QLQ-C30, SF-36) | ||

| Santa Mina et al. [17] | No differences | PRO (FACT-F) | ||

| Sajid et al. [31] | EXCAP: Significant reduction (P = 0.04) measured with SPPB Wii-fit: no differences | PRO (SPPB) | ||

| Taaffe et al. [35] | Significant reduction in fatigue (P = 0.005) and increased vitality (P < 0.001) measured with EORTC-QLQ-C30 and SF-36 resp. | PRO (EORTC-QLQ-C30; SF-36) | ||

| Aerobic + resistance training + dietary advice | Bourke et al. [14] | Significant reduction at 12 weeks (P = 0.002) and 6 months (P = 0.006) measured with FACT-F | PRO (FACT-F) | |

| Bourke et al. [20] | Significant reduction at 12 weeks (P < 0.001) and 6 months (P = 0.010) measured with FACT-P | PRO (FACT-P) | ||

| Impact + resistance training | Taaffe et al. [35] | Significant reduction of fatigue (P = 0.005) and increased vitality (P < 0.001) | PRO (EORTC-QLQ-C30; SF-36) | |

| Resistance training | Segal et al. [9] | Significant reduction (P = 0.002) | PRO (FACT-F) | |

| Sharma et al. [11] |

Significant reduction after 12 weeks (P = 0.010) and 24 weeks (P = 0.002) Per-group analysis: significant reduction after 24 weeks (P = 0.04) |

PRO (SF-36) | ||

| Santa Mina et al. [17] | No differences | PRO (FACT-F) | ||

| Nilsen et al. [25] | No differences | PRO (EORTC- QLQ-C30) | ||

| Dawson et al. [37] | No differences | PRO (BFI) | ||

| Soy protein | Sharma et al. [11] | No differences | PRO (SF-36) | |

| Decreased libido + sexual function | Aerobic + resistance training | Culos-Reed et al. [12] | No difference between groups or effect over time in sexual function | PRO (EPIC) |

| Cormie et al. [15] | Significant difference in percentage of major interest in sex (P = 0.024) and maintenance in level of sexual activity (P = 0.045) No change in any level of sexual interest or sexual function | PRO (QLQ-PR25) | ||

| Cormie et al. [24] |

Significant less decline in sexual function (P = 0.028), no difference in sexual activity Per-group-analysis over time: decline in sexual activity (P = 0.012), no change in sexual function |

PRO (QLQ-PR25) | ||

| Information booklet | Walker et al. [19] | No significant differences. Sexual activity at baseline: 64.3% versus 38.5% (control), after 6 months: 25% versus 0% (control) | PRO (PAIR inventory: DAS scale, sexual activity) | |

| Soy protein | Sharma et al. [11] | No differences | PRO (IIEF, WSFS) | |

| Overweight | Aerobic training | Hvid et al. [16] |

Body composition: no differences Per-group analysis: reduction in BMI (P < 0.0001), weight (P < 0.0001), fat mass (P < 0.01), fat percentage (P < 0.05), trunk fat mass (P < 0.01) Blood biomarkers: no differences Per-group analysis: Increase in HDL over time. No differences in LDL, total cholesterol, triglycerides |

Body composition and blood biomarkers |

| Santa Mina et al. [17] | No differences | Body composition | ||

| Aerobic training + dietary advice | O’neill et al. [26] |

Body composition: significant reduction (all P = 0.001), waist-to-hip ratio (P = 0.009) No difference in lean body mass or mid-upper arm muscle area |

Body composition | |

| Aerobic + resistance training | Culos-Reed et al. [12] |

Body composition: significant reduction in waist girth (P = 0.044) and neck girth (P-0.019), no difference in BMI Per-group analysis: no difference in BMI |

Body composition | |

| Galvao et al. [13] |

Body composition: significant increase in total lean mass (P = 0.047), upper limb (P < 0.001), lower limb (P = 0.019), appendicular skeletal mass (P = 0.03). No change in weight total body fat mass trunk fat mass or percentage body fat Blood biomarkers: Significant decrease in CRP (P = 0.008). No change in other markers |

Body composition and blood biomarkers | ||

| Cormie et al. [24] |

Body composition: significant reduction in appendicular lean mass (P = 0.019), whole body fat mass (P = 0.001), whole body percentage fat (P < 0.001), trunk fat mass (P = 0.008). No differences in total body mass, visceral fat mass or body lean mass Blood biomarkers: significant reduction in HDL total cholesterol ratio (P = 0.028). No differences in other biomarkers |

Body composition and blood biomarkers | ||

| Sajid et al. [31] |

EXCAP: Body composition: no differences Wii-fit: Body composition: decrease in lean mass for the Wii-fit group (P = 0.045), |

Body composition | ||

| Wall et al. [36] |

Body composition: increase in lean body mass (P = 0.015), decrease in total fat mass (P = 0.020), trunk fat mass (P < 0.001), body fat percentage (P = 0.001), no change in weight Blood biomarkers: no differences |

Body composition and blood biomarkers | ||

| Aerobic + resistance training + dietary advice | Bourke et al. [14] | No differences | Body composition | |

| Bourke et al. [20] | No differences | Body composition | ||

| Gilbert et al. [28] |

Body composition: significant increase in skeletal muscle mass (P = 0.03), no difference in BMI or body fat mass Blood biomarkers: no differences |

Body composition and blood biomarkers | ||

| Educational support program | Taylor et al. [10] | No differences | Body composition | |

| Football training | Uth et al. [21] |

Significant increase in lean body mass (P = 0.02), no change in body fat percentage, body fat mass Per-group analysis: significant increase in lean body mass (P = 0.02), no change in body fat percentage or body fat mass |

Body composition | |

| Uth et al. [32, 33] | No differences | Body composition | ||

| Resistance exercise | Uth et al. [32, 33] | No differences | Body composition | |

| Segal et al. [9] | No differences | Body composition | ||

| Santa Mina et al. [17] | No differences | Body composition | ||

| Winters-stone [23] |

Significant reduction in total fat mass in covariance analysis (P = 0.02), not in ITT analysis No significant change in body lean mass, percentage body fat, weight or trunk fat mass |

Body composition | ||

| Nilsen et al. [25] | Significant increase in LBM in lower extremities (P = 0.002) and upper extremities (P = 0.048), appendicular skeletal muscle mass (P = 0.001). No change in total, trunk lean mass, total fat mass, trunk fat mass, percentage fat mass, weight, or BMI | Body composition | ||

| Nilsen et al. [29, 30] |

No significant difference in mitochondrial proteins or indicators of muscle cellular stress: HSP70 B-crystallin; ubiquitin; ubiquittinated proteins Per-group analysis: change over time in HSP70 (P = 0.03) |

Muscles biopsies m. Vastus lateralis: protein concentrations, HSP70, Alpha B-crystalline, HSP27, HSP27, HSP60, COXIV, Citrate synthase Ubiquitin | ||

| Nilsen et al. [29, 30] |

Significant change in total muscle fiber in favor for intervention group (P = 0.04) Significant increase in type II fibers for intervention group (P = 0.03); no change myonuclei number |

Muscle biopsies m. Vastus lateralis: histology, muscle fiber CSA, myonuclei, satelite cells, protein concentrations | ||

| Dawson et al. [37] |

Significant increase in lean mass, appendicular skelet mass (P = 0.02), sacropenic index (P = 0.02), fat free mass (P = 0.04). Significant decrease in waist circumference (P = 0.01), and percentage body fat (P = 0.01). No difference in fat mass or total mass Blood biomarkers: No difference |

Body composition | ||

| Hot flushes | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | Stefanopoulou et al. [27] |

Decreased hot flashes problem rating (P = 0.001) and reduced frequency at 6 weeks (P = 0.02). No difference at 32 weeks |

PRO (HFNS) |

| Soy protein | Sharma et al. [11] |

Difference in favor of the placebo group at 12 weeks (P = 0.04). No difference at 6 weeks Per-group analysis: no difference in vasomotor symptoms |

PRO (Blatt-Kupperman scale) | |

| Vitolin et al. [18] |

No differences Per-group analysis: significant decrease of vasomotor symptoms (P < 0.001), hot flushes severity (P < 0.001), hot flushes symptom severity score (P < 0.001) |

PRO (HFSS, HFSSS) | ||

| Gynaecomastia | Aerobic training | Santa Mina et al. [17] | No difference | Body composition |

| Resistance training | Santa Mina et al. [17] | No difference | Body composition | |

| Cardiovascular | Aerobic training | Hvid et al. [16] |

No significant difference in VO2 max (ml(O2)/min per kg), VO2max (ml(O2)/min Per-group analysis: increase in VO2 max (ml(O2)/min per kg) (P < 0.0001), VO2 max (ml(O2)/min) (P < 0.001). |

Physical test (VO2max) |

| No difference | ||||

| Santa Mina et al. [17] | No difference | Physical test (VO2max) | ||

| Aerobic training + dietary advice | O’neill et al. [26] | Significant change (P = 0.001) | Physical test (6-m walk test) | |

| Aerobic + resistance training | Culos-Reed et al. [12] |

No difference Per-group analysis: significant reduction of systolic blood pressure (P = 0.011) and diastolic blood pressure (P = 0.004) |

Blood pressure | |

| Galvao et al. [13] | No difference | Physical test (400 m walk test) | ||

| Cormie et al. [24] |

Significant increase in VO2 max (P = 0.004) and 400 m walk (P = 0.009) No change in blood pressure |

Physcial test (VO2 max: 400-m walk test) Blood pressure | ||

| Taaffe et al. [35] |

No differences Per-group analysis: cardiovascular fitness improved ART: P < 0.001 |

Physical test (400 m walk) | ||

| Wall et al. [36] |

Significant increase in VO2 Max (L min) and VO2 Max (ml/kg) (P = 0.033), fat oxidation (P = 0.037) No change in RMR, carbohydrate oxidation, peripheral systolic, diastolic RR or MAP, central diastolic RR or MAP, peripheral augmentation index, central augmentation pressure, central augmentation, index, pulse-wave velocity |

Physical test (Respiratory gas analysis, VO2 Max), blood pressure, blood samples | ||

| Aerobic + resistance training + dietary advice | Bourke et al. [20] |

Significant improvement in aerobic exercise tolerance at 12 weeks (P < 0.001) and 6 months (P < 0.001) No difference in systolic blood pressure |

Physcial test (aerobic exercise tolerance), blood pressure | |

| Aerobic, balance, resistance exercise + dietary advice | Gilbert et al. [28] |

Treadmill walk time improved at 12 and 24 weeks (P < 0.001) Difference in FMD at 12 weeks (P = 0.04). No difference in GTN dilatation, systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure |

Physical test (VO2 max, exercise tolerance: walking test), blood pressure | |

| Football training | Uth et al. [21] |

No significant difference between groups Per-group -analysis: VO2 max increased in the intervention group (1.0 ml/kg/min) P = 0.02 |

Physical test (VO2 max: 4-min walking test; incremental test to exhaustion, pulmonary gas exchange measurements; heart rate monitors) | |

| Impact + resistance training | Taaffe et al. [35] | No differences | Physical test (400 m walk) | |

| Resistance training | VO2max improvement (P = 0.41), also after adjustment for covariates (P = 0.38) | |||

| Santa Mina et al. [17] | Significant improvement compared to control group | Physical test (VO2 max) | ||

| Dawson et al. [37] | No differences | Blood pressure | ||

| Insulin resistance | Aerobic training | Hvid et al. [16] |

No difference in fasting glucose, glucose AUC or insulin AUC compared to control group Per-group analysis: significant change in fasting glucose (P < 0.05), no change in glucose AUC or insulin AUC |

Physical test (VO2 Max OGTT Euglycemic– hyperinsulinemic clamp), blood biomarkers |

| Aerobic + resistance training | Galvao et al. [13] | No differences | Blood biomarkers | |

| Cormie et al. [24] | No differences | Blood biomarkers | ||

| Wall et al. [36] | Significant change for glucose (P < 0.001). No change for Hba1c or insulin | Blood biomarkers | ||

| Aerobic + resistance training + dietary advice | Bourke et al. [14] | No differences | Blood biomarkers | |

| Resistance training | Winters-stone [23] | No differences | Blood biomarkers | |

| Dawson et al. [37] | No differences | Blood biomarkers | ||

| Osteoporosis | Aerobic + resistance training | Cormie et al. [24] | No differences | Body composition, blood biomarkers |

| Football training | Uth et al. [32] |

Bone mineral content: significant increment in total body BMC (P = 0.013), leg BMC (P < 0.001) Bone mineral density: no differences Blood biomarkers: significant change P1NP (P = 0.008) and osteocalcin (P = 0.002), no change in CTX |

Body composition, blood biomarkers | |

| Uth et al. [32] |

Bone mineral density: significant increment in left total hip (P = 0.030), right total hip (P = 0.015), left femoral shaft (P = 0.015), right femoral shaft (P = 0.016). No difference in right femoral neck, left femoral neck, lumbar spine L2–L4 Blood biomarkers: no differences |

Body composition, blood biomarkers | ||

| Resistance training | Nilsen et al. [25] | No differences | Body composition | |

| Kim et al. [34] | No differences | Body composition |

Table 3.

Methodological quality assessment tool for randomized controlled trials

| Random sequence generation (Selection bias) | Allocation concealment (Selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (attrition bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Other bias | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segal [9] | 2003 | + | + | − | ? | − | + | + |

| Taylor [10] | 2006 | − | − | − | + | + | + | − |

| Sharma [11] | 2009 | + | + | + | + | ? | + | − |

| Culos-Reed [12] | 2010 | + | + | − | + | ? | + | − |

| Galvao [13] | 2010 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| Bourke [14] | 2011 | + | ? | − | + | + | ? | ? |

| Cormie [15] | 2013 | + | + | − | ? | + | + | + |

| Hvid [16] | 2013 | − | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| Santa Mina [17] | 2013 | ? | + | − | + | + | + | − |

| Vitolins [18] | 2013 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Walker [19] | 2013 | ? | ? | − | ? | + | + | − |

| Bourke [20] | 2014 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| Uth [21] | 2014 | + | + | − | + | + | + | − |

| Winters-Stone [22, 23] | 2015 | ? | ? | − | + | + | + | − |

| Cormie [24] | 2015 | + | + | − | ? | + | + | + |

| Nilsen [25] | 2015 | + | ? | − | + | + | + | + |

| O’Neill [26] | 2015 | + | + | − | − | + | + | ? |

| Stefanopoulou [27] | 2015 | + | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| Gilbert [28] | 2016 | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Nilsen [29] | 2016 | + | ? | − | + | − | ? | − |

| Nilsen [30] | 2016 | + | ? | − | + | − | ? | − |

| Sajid [31] | 2016 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Uth [32] | 2016 | + | + | − | + | + | ? | − |

| Uth [33] | 2016 | + | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| Kim [34] | 2017 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − |

| Taaffe [35] | 2017 | + | + | − | + | − | + | ? |

| Wall Dawson [36, 37] |

2017 2018 |

+ + |

+ + |

− − |

+ − |

− + |

+ ? |

+ + |

Risk of bias summary for each trial included in the systematic review as evaluated by authors

+ low risk of bias; ? Some concerns are risk of bias; − high risk of bias

Psychological side effects

Quality of life

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is perceived physical and mental health over time either by an individual or by a group. The influence of lifestyle interventions on the quality of life for patients on ADT was examined in 16 studies [9–15, 17, 18, 20, 23–27, 34, 36].

Ten different questionnaires were used to measure HRQOL. Some of the questionnaires are developed to examine health-related quality of life in general (STAI; SF-36; EORTC-QLQ- C30; QLQ-PR25; PSS; FACT-G; LFDI). Others are used to investigate prostatic disease-specific quality of life or aspects of quality of life (FACT-P; PORPUS; EPIC). Eleven studies investigated the effects of physical exercises, three combined physical exercises with dietary advice, and two investigated the effect of soy consumption. In four studies, a positive effect of exercise only was noted [9, 13, 24, 36]. Two out of six studies investigating the effect of resistance training found a positive effect on the health-related quality of life and in one of these studies, an improved disease-specific quality of life had been found [36]. Aerobic and resistance training combined showed a positive effect in two out of four studies [13, 24]. In these two studies, only specific domains were significantly improved. For details, see Table 2. Variable results were found when combining exercises with dietary advice. All three studies found positive effects on different aspects of quality of life [15, 20, 26]. Bourke et al. found an improvement in the prostatic disease-specific quality of life after 12 weeks of training, but this was only temporary since the effect disappeared after 24 weeks [20]. One study investigated the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on quality of life, but failed to show an improvement. Two studies investigated the effect of soy consumption. Vitolins et al. found an improved HRQOL as well as an improved disease-specific quality of life after consumption of soy protein, while Sharma et al. failed to show any effect [11, 18].

Depression

In the treatment of PCa, ADT use is associated with depression. Five studies focused on depression [10, 12, 24, 27, 36]. Aerobic and/or resistance training failed to show a beneficial effect [12, 24, 36]. Applied cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for a period of four weeks did not show a beneficial effect [27]. A lifestyle activity program or an educational support program did not influence depression scores using CES-D [10].

Fatigue

Fatigue is a phenomenon, which is difficult to measure or define. Fatigue is experienced by patients receiving ADT and is associated with decreased levels of testosterone and reduction of skeletal muscle mass may contribute to fatigue. Influence of lifestyle interventions was examined in fourteen studies: ten investigated the effects of physical exercises, three combined physical exercises with dietary advice, and one investigated the effect of soy consumption [9, 11–14, 17, 20, 24–26, 31, 35, 36]. Soy consumption showed no effect [11].

Different exercise modalities yield conflicting results in relation to fatigue. Generally speaking, in half of the studies, a reduction in fatigue was noted. Combining exercises with dietary advice showed a beneficial effect in two studies [14, 20]. Another study failed to show improvement [26].

Decreased libido and sexual function

Since androgens play an essential role in maintaining sexuality, e.g., libido and erectile function, it is obvious that ADT causes a decrease in sexual activity and may result in a variety of sexual problems. Five studies investigated methods to counteract decreased libido and erectile function [11, 12, 15, 19, 24]. Aerobic and resistance exercises were examined in three studies in which contradictory findings were reported. In 2013, Cormie et al. found maintenance of major interest in sex as well as sexual activity in the exercise group. No change in sexual function was noted. In 2015, Cormie et al. reported a diminished decline in sexual function in favor of the exercise group. In per-group analysis, a decline in sexual activity was found without change in sexual function [24]. Culos-Reed et al. found no differences [12].

Patient information concerning the side effects of ADT followed by an educational partner session failed to show an effect on libido, measured by the PAIR and DAS-scores which, respectively, assess the current level of intimacy in one’s relationship and the relationship adjustment. Couples participating in the intervention were more successful at maintaining sexual activity [19]. Soy protein consumption did not influence libido or sexual function [11].

Physical side effects

Gynecomastia

Gynecomastia may develop in ADT. In one study, gynecomastia was measured by skinfold thickness and was not influenced by aerobic or resistance training [17].

Hot flushes

Hot flushes are defined as intense heat sensation, flushing, and perspiration involving face and trunk. Anxiety and palpitations may occur. ADT may induce these complaints because the decline in LH and FSH causes the release of hypothalamic catecholamines disrupting the thermoregulation center in the upper hypothalamus. CBT temporarily lowers the occurrence of hot flushes and problem rating in men [27]. Only at 6 weeks, significance was reached, and it was no longer significant at 32 weeks. Two studies examined the effect of soy consumption on hot flushes. One study found a significant decrease of ADT-associated vasomotor symptoms in the soy protein and placebo group [18]. Sharma et al. observed no change.

Surprisingly, a significant difference in favor of the placebo group was found [11].

Overweight

ADT may cause metabolic effects including dyslipidemia, elevated fasting serum glucose, weight gain, and increase in fat mass. C-reactive protein (CRP) might be a marker of adverse metabolic effects. Seventeen studies reporting on exercise programs of varying duration, frequency, intensity, and degree of supervision showed conflicting results [9, 10, 12–14, 16, 17, 20–26, 28–32, 36, 37]. These articles mention aspects of body composition amounting to sixteen different items: weight, BMI, waist circumference, hip circumference, waist and neck girth, waist-to-hip ratio, mid-upper arm muscle area, total fat mass, percentage body fat, trunk fat mass, visceral fat mass, body lean mass, appendicular lean mass, and skeletal muscle mass. The effect of aerobic and/or resistance training on body composition was examined in thirteen studies. Three of these studies added dietary advice [14, 20, 28].

Beneficial effects on one or multiple items reflecting body composition were found in eight of these studies (Table 2).

O’neill et al. investigated the effect of aerobic training and dietary advice and showed an improvement in body composition [26]. Two studies examined the effect of supervised football training [21, 32]. One study lasted 12 weeks, the other 32 weeks. Initially, a significant increase in lean body mass was reached after 12 weeks [21]. At 32 weeks, this effect ceased to be significant. Endurance training showed an improvement of body composition [16]. Metabolic syndrome is a clustering of at least three out of five following medical conditions: hypertension, hyperglycemia, abdominal obesity, high serum triglycerides, and a low high-density lipoproteins (HDL).

Blood biomarkers reflecting these changes were examined in six studies. A decrease in HDL/total cholesterol ratio was found by Cormie et al., who investigated the effects of a 12-week program combining aerobic and resistance training [24]. An improvement in HDL was found over time after a program of endurance training [16].

No other studies reported beneficial effects. The influence of aerobic and resistance training on CRP showed contradictory results. One study found a positive effect [13], and two studies found no change [24, 36]. On microscopic level, the effect of resistance training in biopsies of the m. vastus lateralis was reported [29, 30]. An increase in total muscle fibers and type II fibers was shown [29]. Muscle atrophy is associated with reduced mitochondrial function and increased muscle cellular stress, reflected by different heat shock proteins. Only HSP70 improved significantly [30].

Cardiovascular health

Factors influencing cardiovascular health are manifold: lipid profile, blood pressure, BMI, endothelial cell function, pro-inflammatory factors, and insulin resistance. ADT has a negative impact on these factors. Besides, there is an association between ADT and the occurrence of serious cardiac arrhythmias. Eleven studies investigated the effect of physical exercise of which three studies added dietary advice [12, 13, 16–18, 24, 26, 28, 36, 37]. The results of these studies are contradictory. With respect to blood pressure, four studies found no effect on systolic or diastolic blood pressure between the groups [12, 20, 24, 28]. Culos-Reed et al. found a change in systolic and diastolic blood pressure over time in the aerobic and resistance training group [12]. Using flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) as a measure, an improvement in the exercise combined with dietary advice group was found [28]. The effect of training on maximum oxygen utilization (VO2 max) was investigated in five studies [17, 18, 24, 36, 37]. Most of these studies consisted of a mixture of aerobic and/or resistance training. Uth et al. used football training. Almost consistently, an improvement was found.

Resistance training scored better in increasing cardiovascular fitness than aerobic [17, 18]. Four studies found a significant improvement on cardiovascular fitness after physical exercises, measured by different tests [13, 26, 29, 35].

Insulin resistance

It is not completely understood how ADT therapy deregulates glucose metabolism. Possibly hypogonadism, secondary to obesity, alters fatty acid metabolism or changes in skeletal muscle may play a role. The influence of exercise on insulin resistance was measured in seven studies [13, 14, 16, 22–24, 36, 37]. One study added dietary advice. A glucose-lowering effect of exercise was shown in two studies [16, 36]. Wall et al. showed an improvement for glucose metabolism in combined aerobic and resistance training [36]. Hvid et al. investigated the effect of endurance training on insulin resistance in men on ADT compared to healthy males and found a difference in fasting glucose over time in the per-group analysis [16].

Using the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), no differences over time were found between the groups with regard to fasting glucose, fasting insulin, glucose AUC, and insulin AUC [16]. Biomarkers: IGF-1, insulin, IFGBP-1 and IGFBP-3, and HBA1c failed to show a difference in any of the studies.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a major concern in men undergoing ADT therapy, especially with prolonged use. Five studies investigated the effect of exercise modalities on osteoporosis [24, 25, 32–34]. We were unable to find any studies focusing on dietary advice. Dual x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA-scan) was used in all studies in order to examine bone mineral density (BMD) and bone mineral content (BMC). Blood biomarkers were examined in four studies. Biomarkers were alkaline phosphatase, P1NP, N-telopeptide, N-telopeptide/creatinine ratio, vitamin D, osteocalcin, CTX, NTX, and BS-ALP. Only Uth was able to show a significant improvement in different markers of osteoporosis. He found an increment in BMC after 12 weeks of supervised football training [33]. Initially, BMD remained unchanged after 12 weeks of training [33], whereas after 32 weeks, an increase in BMD was found in the total hip and femoral shaft [32]. P1NP and osteocalcin were the only bone formation markers that showed a significant change. After 12 weeks, there was an increase in these markers [32] After prolonged training (32 weeks), this increase no longer was significant [32].

Discussion

This study focuses on lifestyle interventions to reduce the deleterious side effects of ADT. Twenty-nine RCTs reported the effect of different lifestyle interventions. The effect of exercises in different modalities and intensities was studied including measures such as dietary advice, self-education, CBT, or educational support program. We excluded therapies like prescribing calcium and vitamin D.

Regarding psychological effects, contradictory results were found. Many different questionnaires were used to examine the effect of lifestyle interventions on HRQOL, which make it hard to compare different outcomes and therefore it is difficult to make a straightforward conclusion about the effect of certain interventions.

Combining exercise with diet seems to have the most beneficial effects on HRQOL; all studies regarding this combination showed a significant improvement [15, 20, 26]. Soy protein consumption was found in only one study to have a beneficial effect.

An earlier study found that ADT use conferred a 41% increased risk of depression [38]. In this review, we were unable to find any difference in the occurrence of depression after applying lifestyle interventions, whereas in two studies an improvement of QOL was noted in absence of improvement of depression score [24, 37]. Tentative explanations for these outcomes can be the following. Both studies used different questionnaires to score quality of life and the occurrence of depression, making it difficult to compare them. In our review, we only noted the truly significant findings, but in the study of Cormie, where an improvement in various subscales of QOL was observed, a borderline significance was found in the depression score with a P value of 0054; this might be interpreted as a trend in improvement of physiological well-being [24].

There were many different tools used to examine fatigue. Some used general questionnaires, and others applied prostate-specific tools (FACT-F) [9, 14, 17, 20, 24]. Although there was a lack in using a common tool, different lifestyle interventions reduced fatigue and increased vitality. All studies used in this review examined physical exercises, sometimes combined with dietary advice. However, no attention was given to other lifestyle adjustments, such as smoking, alcohol use, or a balanced diet.

With regard to libido and sexual function, a possible beneficial effect of aerobic and resistance training was found [15, 24]. It is noteworthy that consuming soy protein did not have any effect [11]. Considering the age group for which ADT therapy is applied, we can expect a general natural decline of libido and sexual function.

Gynecomastia may very well occur after weight gain. Only one author reported on this subject [17]. This might reflect a disbelief in the effect of lifestyle changes on gynecomastia. A variety of medical therapies exist such as radiation therapy or lipolysis [39].

Two strategies were examined to reduce vasomotor symptoms. Although soy proteins appears to be successful in treating hot flushes in postmenopausal women [40], in men on ADT, they are unsuccessful. CBT appears to be helpful in managing hot flushes. Limitations of this study were the small sample size and short period of self-guided therapy. Further research might look into additional variables such as caffeine intake and other specific health problems.

In this study, we divided the metabolic changes into three subcategories: overweight, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular health. These categories are interrelated. Concerning insulin resistance, studies failed to show a difference between men with ADT undergoing physical exercises or not, when measured by fasting glucose. Endurance training, however, showed no differences in OGTT between men on ADT undergoing exercises versus healthy men [16]. No trial used the novo diabetes mellitus as an outcome.

Overweight was examined in 17 studies. All studies investigated the effect of exercise, and four studies added nutritional advice. Evidence was found that solely exercise or exercise combined with nutritional advice may decrease overweight. The influence of a dietary advice only on obesity hasn’t been investigated. Earlier studies showed the major impact of an appropriate diet in the prevention of obesity in the healthy old male population [41].

Considering osteoporosis, one study suggests that regularly practicing football may mitigate ADT-induced decline in BMD. However, aerobic or resistance training failed to show this decline. Future studies should investigate the effects of different exercise modalities.

National osteoporosis foundation recommends a daily calcium intake of 1200 mg and supplemental vitamin D of 800–1000 IU to maintain bone health [42]. In this review, there was not one study, which focused on an adequate intake as described above. As mentioned earlier, we did not include RCTs in which calcium and Vitamin D were prescribed. A systematic review conducted in 2012, which investigated the effect of calcium and vitamin D suppletion in men with PCa using ADT showed conflicting effects [43]. It would be interesting to conduct studies in which dietary advice is given to promote sufficient intake of calcium and vitamin D and investigate this effect on the development of osteoporosis in patients on ADT.

A number of limitations in this review must be considered. Firstly, we focused on two databases, PubMed and Medline, since these two are the most widely used and recognized. Secondly, there was substantial heterogeneity in life style interventions, in which some interventions were investigated frequently, while other interventions only once. This makes it impossible to compare the effects of different strategies and draw conclusions about the efficacy of these interventions. Additionally, we did not investigate the effect of duration of exercise, dietary advice, or other behavioral components.

There was a variety in quality of the different RCTs. Especially, the prevention of performance bias was often inadequate, due to the fact it was impossible to blind participants following lifestyle programs. Despite these limitations, evidence suggests that lifestyle interventions may have a beneficial effect on ADT-mediated side effects.

Conclusions

Adverse effects of ADT are manifold as well as the various lifestyle interventions aimed to alleviate these side effects. Physical exercises demonstrated to have a mainly positive effect on cardiovascular health. Contradictory results were found regarding quality of life, libido, fatigue, insulin resistance, overweight, and osteoporosis. No effect was found regarding depression and gynecomastia. Regarding dietary advice, soy protein showed no beneficial effect on libido or fatigue. No other studies allowed conclusions on dietary advice solely. A positive effect was shown with CBT on the occurrence of hot flushes. Other behavioral components failed to show a significant effect regarding side effects. Further research is necessary to identify the most effective interventions for the individual patient.

Funding

This study was funded by AstraZeneca BV, the Netherlands.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huggins C. Studies on prostatic cancer. I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and of androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Research. 1941;1(4):293. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.22.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. European Urology. 2014;65(2):467–479. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denis L, Murphy GP. Overview of phase III trials on combined androgen treatment in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer. 1993;72(12 Suppl):3888–3895. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931215)72:12+<3888::AID-CNCR2820721726>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor LG, Canfield SE, Du XL. Review of major adverse effects of androgen-deprivation therapy in men with prostate cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(11):2388–2399. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yunfeng G, Weiyang H, Xueyang H, Yilong H, Xin G. Exercise overcome adverse effects among prostate cancer patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy: An update meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(27):e7368. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner Jason R, Livingston Patricia M, Fraser Steve F. Effects of exercise on treatment-related adverse effects for patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen-deprivation therapy: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(4):335–346. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.5523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segal RJ, Reid RD, Courneya KS, et al. Resistance exercise in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(9):1653–1659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmack Taylor CL, Demoor C, Smith MA, et al. Active for Life After Cancer: A randomized trial examining a lifestyle physical activity program for prostate cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2006;15(10):847–862. doi: 10.1002/pon.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma P, Wisniewski A, Braga-Basaria M, et al. Lack of an effect of high dose isoflavones in men with prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy. Journal of Urology. 2009;182(5):2265–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Culos-Reed SN, Robinson JW, Lau H, et al. Physical activity for men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: Benefits from a 16-week intervention. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(5):591–599. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galvao DA, Taaffe DR, Spry N, Joseph D, Newton RU. Combined resistance and aerobic exercise program reverses muscle loss in men undergoing androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer without bone metastases: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(2):340–347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourke L, Doll H, Crank H, Daley A, Rosario D, Saxton JM. Lifestyle intervention in men with advanced prostate cancer receiving androgen suppression therapy: A feasibility study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2011;20(4):647–657. doi: 10.1158/1055-965.EPI-10-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cormie P, Newton RU, Taaffe DR, et al. Exercise maintains sexual activity in men undergoing androgen suppression for prostate cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013;16(2):170–175. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2012.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hvid T, Winding K, Rinnov A, et al. Endurance training improves insulin sensitivity and body composition in prostate cancer patients treated with androgen deprivation therapy. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2013;20(5):621–632. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santa Mina D, Alibhai SMH, Matthew AG, et al. A randomized trial of aerobic versus resistance exercise in prostate cancer survivors. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2013;21(4):455–478. doi: 10.1123/japa.21.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vitolins MZ, Griffin L, Tomlinson WV, et al. Randomized trial to assess the impact of venlafaxine and soy protein on hot flashes and quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(32):4092–4098. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker LM, Hampton AJ, Wassersug RJ, Thomas BC, Robinson JW. Androgen deprivation therapy and maintenance of intimacy: A randomized controlled pilot study of an educational intervention for patients and their partners. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;34(2):227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourke L, Gilbert S, Hooper R, et al. Lifestyle changes for improving disease-specific quality of life in sedentary men on long-term androgen-deprivation therapy for advanced prostate cancer: A randomised controlled trial. European Urology. 2014;65(5):865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uth J, Hornstrup T, Schmidt JF, et al. Football training improves lean body mass in men with prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2014;24(Suppl 1):105–112. doi: 10.1111/sms.12260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winters-Stone KM, Dieckmann N, Maddalozzo GF, Bennett JA, Ryan CW, Beer TM. Resistance exercise reduces body fat and insulin during androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2015;42(4):348–356. doi: 10.1188/15.ONF.348-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winters-Stone KM, Dobek JC, Benett JA, et al. Resistance training reduces disability in prostate cancer survivors on androgen deprivation therapy: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2015;96(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cormie P, Galvao DA, Spry N, et al. Can supervised exercise prevent treatment toxicity in patients with prostate cancer initiating androgen-deprivation therapy: A randomised controlled trial. BJU International. 2015;115(2):256–266. doi: 10.1111/bju.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilsen TS, Raastad T, Skovlund E, et al. Effects of strength training on body composition, physical functioning, and quality of life in prostate cancer patients during androgen deprivation therapy. Acta Oncologica. 2015;54(10):1805–1813. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1037008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Neill RF, Haseen F, Murray LJ, O’Sullivan JM, Cantwell MM. A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of a 6-month dietary and physical activity intervention for patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2015;9(3):431–440. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0417-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stefanopoulou E, Yousaf O, Grunfeld EA, Hunter MS. A randomised controlled trial of a brief cognitive behavioural intervention for men who have hot flushes following prostate cancer treatment (MANCAN) Psychooncology. 2015;24(9):1159–1166. doi: 10.1002/pon.3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert SE, Tew GA, Fairhurst C, et al. Effects of a lifestyle intervention on endothelial function in men on long-term androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. British Journal of Cancer. 2016;114(4):401–408. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsen TS, Thorsen L, Kirkegaard C, Ugelstad I, Fossa SD, Raastad T. The effect of strength training on muscle cellular stress in prostate cancer patients on ADT. Endocr Connect. 2016;5(2):74–82. doi: 10.1530/EC-15-0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilsen TS, Thorsen L, Fossa SD, et al. Effects of strength training on muscle cellular outcomes in prostate cancer patients on androgen deprivation therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2016;26(9):1026–1035. doi: 10.1111/sms.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sajid S, Dale W, Mustian K, et al. Novel physical activity interventions for older patients with prostate cancer on hormone therapy: A pilot randomized study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(2):71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uth J, Hornstrup T, Christensen JF, et al. Efficacy of recreational football on bone health, body composition, and physical functioning in men with prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: 32-week follow-up of the FC prostate randomised controlled trial. Osteoporosis International. 2016;27(4):1507–1518. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3399-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uth J, Hornstrup T, Christensen JF, et al. Football training in men with prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: Activity profile and short-term skeletal and postural balance adaptations. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2016;116(3):471–480. doi: 10.1007/s00421-015-3301-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim SH, Seong DH, Yoon SM, et al. The effect on bone outcomes of home-based exercise intervention for prostate cancer survivors receiving androgen deprivation therapy: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Cancer Nursing. 2017 doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taaffe DR, Newton RU, Spry N, et al. Effects of different exercise modalities on fatigue in prostate cancer patients undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: A year-long randomised controlled trial. European Urology. 2017;72(2):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wall BA, Galvao DA, Fatehee N, et al. Exercise Improves VO2max and body composition in androgen deprivation therapy-treated prostate cancer patients. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2017;49(8):1503–1510. doi: 10.1249/mss.0000000000001277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dawson JK, Dorff TB, Todd Schroeder E, et al. Impact of resistance training on body composition and metabolic syndrome variables during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):368. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4306-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nead KT, Sinha S, Yang DD, Nguyen PL. Association of androgen deprivation therapy and depression in the treatment of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Urologic Oncology. 2017;35(11):664.e1–664.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widmark A, Fossa SD, Lundmo P, et al. Does prophylactic breast irradiation prevent antiandrogen-induced gynecomastia? Evaluation of 253 patients in the randomized Scandinavian trial SPCG-7/SFUO-3. Urology. 2003;61(1):145–151. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Husain D, Khanna K, Puri S, Haghighizadeh M. Supplementation of soy isoflavones improved sex hormones, blood pressure, and postmenopausal symptoms. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2015;34(1):42–48. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2013.875434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cermak NM, Res PT, de Groot LC, Saris WH, van Loon LJ. Protein supplementation augments the adaptive response of a skeletal muscle to resistance-type exercise training: A meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;96:1454–1464. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.037556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weaver CM, Alexander DD, Boushey CJ, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and risk of fractures: An updated meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis International. 2016;27(1):367–376. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3386-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Datta M, Schwartz GG. Calcium and vitamin d supplementation during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: A Critical review. Oncologist. 2012;17(9):1171–1179. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]