Abstract

Characterizing the three-dimensional (3D) morphological alterations of microvessels under both normal and seizure conditions is crucial for a better understanding of epilepsy. However, conventional imaging techniques cannot detect microvessels on micron/sub-micron scales without angiography. In this study, synchrotron radiation (SR)-based X-ray in-line phase-contrast imaging (ILPCI) and quantitative 3D characterization were used to acquire high-resolution, high-contrast images of rat brain tissue under both normal and seizure conditions. The number of blood microvessels was markedly increased on days 1 and 14, but decreased on day 60 after seizures. The surface area, diameter distribution, mean tortuosity, and number of bifurcations and network segments also showed similar trends. These pathological changes were confirmed by histological tests. Thus, SR-based ILPCI provides systematic and detailed views of cerebrovascular anatomy at the micron level without using contrast-enhancing agents. This holds considerable promise for better diagnosis and understanding of the pathogenesis and development of epilepsy.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Synchrotron radiation, 3D, Angioarchitecture, Blood vessel, Remodeling

Introduction

Epilepsy is an extremely common neurological disorder, impacting ~ 50 million people worldwide [1]. The term “epilepsy” encompasses a large number of syndromes, ranging from diseases with various etiopathogeneses to recurring spontaneous seizures. The seizures occur due to aberrant neuronal networks, resulting in transient excessive or hyper-synchronous discharges involving several cortical neurons [2, 3]. The exact pathogenesis of epilepsy, however, remains largely unknown. Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), for instance, is a focal form that is usually associated with hippocampal atrophy, sclerosis, axonal sprouting, neuronal loss, and various genetic factors [4–7]. Previous studies have mostly dealt with the neuropathological and neurophysiological aspects of epilepsy. Experimental and clinical research over the past decade suggests that systemic hypertension and cerebral small vessel disease amplify the risk of epilepsy, even in the absence of a clinically-detected stroke [8, 9]. Alterations in the neurovasculature have been shown to be of vital importance as well [10, 11]. Neurovascular units in particular play a significant role in the regulation of nutrient supply, vascular growth, hemodynamics, toxin elimination, and brain protection, thus emphasizing the function of neurons, glia, and vascular endothelium as a whole unit [12]. This link between blood vessels and the blood–brain barrier (BBB) provides a novel perspective from which to explore the possible pathogenesis of epilepsy.

The BBB in the neurovascular unit is a dynamic barrier with a variety of physiological functions, such as regulation of cerebral blood flow, nutrient metabolism, transport, and immunization. The BBB can respond to different pathophysiological signals and induce microvascular remodeling as well as angiogenesis in lesioned areas [13–15]. Following observations of pericytosis during seizures, pericytes have now been reported to introduce a pericyte–microglia-mediated mechanism underlying BBB dysfunction in epilepsy patients [16, 17]. Current research suggests that the induction of microvascular neovascularization and remodeling in the hippocampus seen in TLE may be associated with its chronic progression [18]. Microvascular neovascularization has been reported in the hippocampus of patients with previous TLE and chronic refractory periods. The hippocampus consists of four regions, cornu ammonis 1 (CA1), CA2, CA3, and CA4. In TLE patients, neovascularization has been found in the CA1 and CA3 regions, where metabolism is the most exuberant and, therefore, any changes in vascularization are likely to affect the function and metabolism of these regions [19]. Ndode et al. reported that the total length of hippocampal blood vessels is decreased two days after status epilepticus (SE) is induced in adult rats, but they did not find any change in hippocampal blood volume or blood flow. In addition, the proliferation of endothelial cells and angiogenesis in CA3 have been found at four days and two weeks after SE, respectively [20]. And several highly-expressed angiogenic factors have been detected in the brain tissue of epileptic rats 24 h after seizures [21–23]. Ruba et al. administered sunitinib to block angiogenesis in rats suffering from TLE and found that this resulted in atrophy of the hippocampus and control of seizures [24]. The existing body of research suggests a complex relationship between BBB damage and seizures [20, 25].

Following from all these studies, it can be inferred that the local angioarchitecture undergoes some remodeling after a lesion. However, the relationship between epilepsy and neovascularization is not well characterized, probably due to difficulties in accurately visualizing changes in hippocampal angioarchitecture during seizures. Admittedly, conventional vascular visualization techniques such as histological sections [26, 27], immunostaining [12], and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) have high resolution and can resolve data at the micron level. However, they can only display two-dimensional section structure and are unable to reveal the complex spatial networks of blood vessels. DSA also requires contrast-enhancing agents, which may lead to anaphylaxis and neural poisoning [28]. More recently, high-resolution MRI for the non-destructive microscopic analysis of tissue specimens has been proposed [29, 30]. The brain structure of both normal and CNS disease models (such as intracranial artery dissection [31] and spinal cord injury [32]) visualized using diffusion MRI exhibits excellent contrast between grey and white matter. Despite these advantages, high-field and small-bore MRI remains relatively expensive and difficult to set up and maintain. This technique also has a limitation in terms of unavoidable homogeneity-induced image distortions. Moreover, patients with metal implants are unsuitable for MRI scanning, which limits its general applicability.

Fortunately, the development of synchrotron radiation (SR) has pioneered a new method in the field of biomedical imaging. SR is characterized by high monochromatic photon flux and a wide energy spectrum, emitted with energies ranging from infrared light to hard x-rays [33–35]. Unlike conventional attenuation-contrast imaging, which is based on tissue density variations, state-of-the-art SR is based on the phase-contrast imaging (PCI) model [36, 37]. X-ray PCI exploits differences in the refractive index of different materials to differentiate structures [38], allowing it to clearly define biological soft tissues with weak X-ray absorption capacities without having to resort to contrast-enhancing agents [39]. In recent years, several PCI modalities have been developed, such as interferometry [40], diffraction-enhanced imaging [41, 42], grating-based phase-contrast X-ray imaging [43], and in-line phase contrast imaging (ILPCI) [44].

The simplest X-ray PCI-based method, ILPCI, was the main technique used in the present study [45]. Although it is the simplest method, the principle of ILPCI rests on a complicated phase-retrieval step. The constraints placed on SR source size guarantee good spatial coherence and enhancement of edge signals, enabling the visualization of biological tissue microstructures for preclinical evaluation [46]. This technique has been used to visualize a range of biological structures and phenomena, such as renal arteries [47], morphological changes in intervertebral discs and endplates [48], brain microvasculature [49, 50], neovascularization of hepatocellular carcinoma [51], and the internal microstructure of vessels and nerve fibers in the rat spinal cord [52, 53]. In addition to these, it has also recently been used as a promising tool for epilepsy treatment [54, 55] and breast cancer diagnosis [56, 57]. In the current study, we applied SR imaging to visualize the structural remodeling of cerebral vessels under pathological conditions in a dynamic, non-destructive manner.

Methods and Materials

Experimental Animals

The Animal Ethics Committee of Central South University, Changsha, China, approved the experimental protocols, which were in compliance with experimental animal use and ethical requirements per the Ministry of Health of China.

We used 48 male Sprague-Dawley rats (weighing 230–250 g on average) from the Animal Centre of Central South University, Changsha, China. The rats were randomly divided into four groups (12 rats per group): the first was a normal control group, the second was analyzed one day after seizures, the third was analyzed 14 days after seizures, and the fourth was analyzed 60 days after seizures.

Induction of Seizures

Seizures were induced in the experimental groups by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of an aqueous solution of lithium chloride (125 mg/kg; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), followed after 18–24 h by scopolamine (1 mg/kg, i.p.; Minsheng Pharma, China) to overcome the peripheral cholinergic antagonism induced by pilocarpine (PILO), and finally, treatment with PILO (30 mg/kg, i.p.; Sigma) 30 min after scopolamine administration [58, 59]. Animals in the control group were given saline in the same volume as the drugs administered to the experimental groups. After PILO injection, the animals were observed for a sequence of behavioral alterations following the Racine’s standard criteria [60]; rats classified as stage 4 or 5 were considered to have developed SE. SE was then terminated by i.p. injection of diazepam (7.5 mg/kg) 2 h after its onset to stop or limit the behavioral seizures; the same dose of diazepam was also given to control animals. Additional diazepam (5 mg/kg) was administered if seizures were not reduced efficiently or if they recurred within 1 h of the first diazepam injection [61, 62]. The experimental animals were housed in acrylic cages with free access to food and water, under a 12:12 h light:dark cycle at constant temperature (25°C) and humidity (50% ± 10%).

Sample Preparation

Before transcardiac perfusion, animals were deeply anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate (0.4 mL/kg, i.p.). We then perfused paraformaldehyde (4%) in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at different time points. The rat brains were dissected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h, and then separated for different experiments. Three brains per group were prepared for SR-ILPCI and the remaining three for histological observation. The rinsed brain specimens were fully dehydrated for ILPCI using an ascending ethanol gradient.

Image Acquisition and Post-processing

We performed all experiments with the biomedical application beamline (BL13W1) of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), which is a third-generation synchrotron source [50]. Its average beam current is 180 mA and storage energy is 3.5 GeV. The BL13W1 beamline offers tunable photon energy from 8 to 72.5 keV, with a maximal target size of ~ 5 mm (vertical) × 45 mm (horizontal) at 20 keV. The distance between the downstream detector and sample can be changed from 0 to 8 m. Our samples were fixed on a rotating stage, allowing the detector-to-sample distance to be adjusted by moving the detector along a rail vertical to the axis. High-contrast images were captured by a camera with a charge-coupled device (CCD). A schematic of the equipment used for SR imaging at BL13W1 is shown in Fig. 1A.

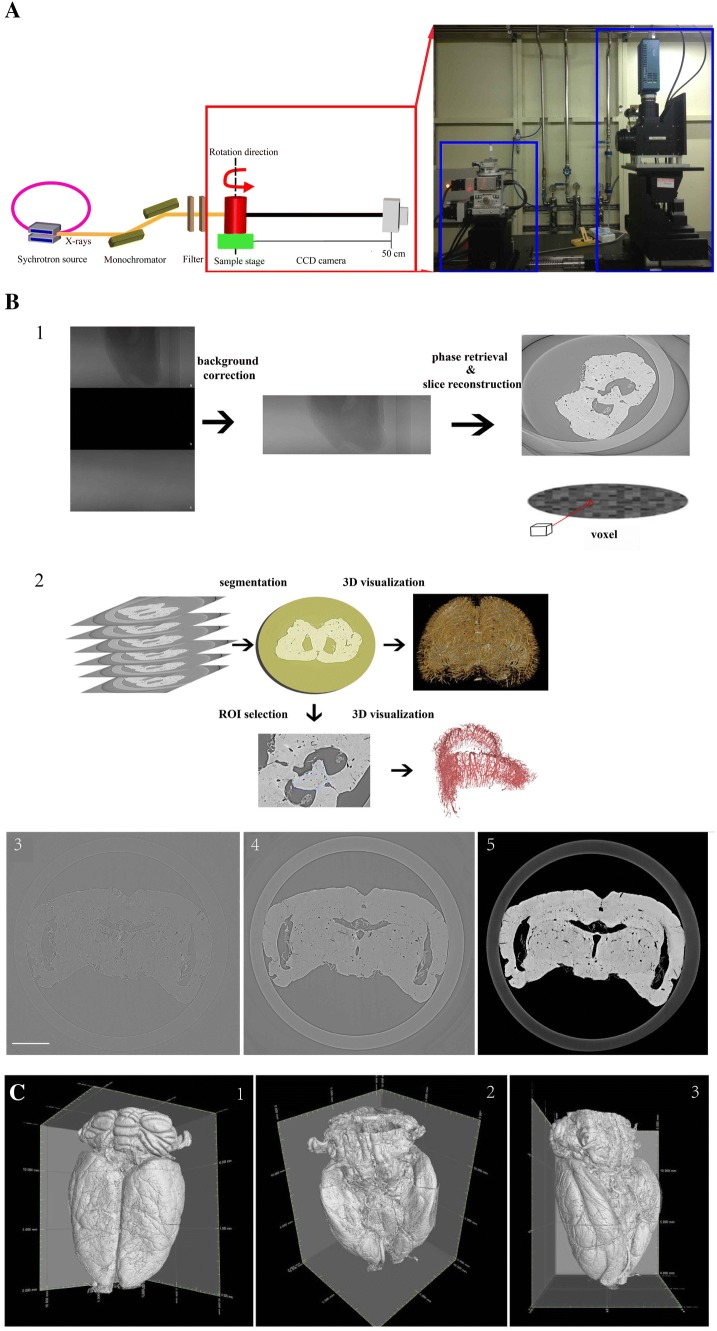

Fig. 1.

Reconstruction procedure and overview of the 3D surface morphology of rat brain. A Schema of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. B Reconstruction procedure, consisting of acquiring CT images, reconstruction of a series of CT slices, and in-depth processing (scale bar, 2 mm). C Overview of the 3D surface morphology of rat brain from dorsal, ventral, and lateral views.

The effective pixel size of the CCD detector was 5.2 μm. To acquire clear, high-contrast images of the vasculature, we set the scanning energy to 20.0 keV and the detector-to-sample distance to 0.5 m. By continuously rotating the samples from 0° to 180° and setting the exposure time to 1.5 s, a total of 900 projection images were acquired. We also recorded flat-field and dark-field images for subtracting background signals, filtering noise, and eliminating small intensity discrepancies. To improve the quality of reconstructed slices, we performed propagation-based phase-contrast extraction with PITRE software (Phase-sensitive X-ray Image processing and Tomography REconstruction – supplied by BL13W1) [63]. According to the principles of phase contrast imaging, the phase and amplitude of X-rays are influenced by interactions with matter, and the forward diffraction can be described by the complex refractive index “n” of the medium (n = 1 – δ + iβ), where δ is the refractive index decrement in relation to the phase shift, and β is the linear absorption coefficient. Based on preliminary experiments, the parameter δ/β was adjusted to 100 during phase extraction. After phase retrieval and reconstruction, intensity scales were reduced and rescaled to a grey value ranging from 0 to 255. The reformatted digital slice images were acquired using fast slice reconstruction software, based on fast Fourier transformation (supplied in PITRE). We then used VG Studio Max 3D reconstruction software v. 3.0 (Volume Graphics GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany), Image Pro Analyzer 3D v. 7.0 (Media Cybernetics Inc., USA) and Amira v. 6.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to render sequential CT slices into 3D microtomography and performed in-depth 3D analysis. A schematic for obtaining CT images and performing final 3D reconstruction is shown in Fig. 1B1. Through these operations, the 3D images of gross cerebral angioarchitecture and hippocampal regional vasculature were reconstructed (Fig. 1B2). Figure 1B3–B5 shows the step-by-step optimized image processing for slice reconstruction; Fig. 1B3 shows the original image used for slice reconstruction; Fig. 1B4 shows background subtraction; and Fig. 1B5 shows phase retrieval before slice reconstruction. Vascular information was further enhanced through filtered de-noising. Thus, the surface microvasculature of normal rat brain was completely exposed to identify multi-level branches of blood vessels on the pia mater (Fig. 1C).

As described previously, the network analysis mainly incorporated segmentation, skeletonization, and vectorization [49, 64]. We used color codes to define vasculature of different diameters. Using the geometric information of blood vessels and vascular corrosion algorithms, the centerline of the blood vessel (a line connecting points equidistant from both edges of the vessel) was extracted from the 3D images [65]. The vessel centerline provided detailed 3D topological data for subsequent complex morphometric analysis. The distance from the edge of the vessel to the centerline varied with diameter, so we constructed intuitive 3D images to determine the cerebral vascular diameter distribution, by which tortuosity can be measured.

Lastly, we used vascular analysis modules to calculate a series of parameters such as vascular surface area, vessel diameter, the number of vascular bifurcations, and the number of vascular segments for further analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Animals were perfused with paraformaldehyde, as described earlier, at the time of euthanasia. The samples were cryoprotected overnight in 30% sucrose in PBS, embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and then cut into 10-µm sections. We collected coronal sections and washed them three times with PBS. CD31 antigen unmasking was done by treatment with PBS containing 1 µg/mL proteinase K for 15 min at room temperature. The sections were blocked with PBS containing 0.25% Triton and 20% normal horse serum for 90 min at room temperature. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody against CD31 (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The sections were washed thrice in PBS and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for 1 h at room temperature. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, we first stained the sections using a diaminobenzidine kit (Maixin, Fuzhou, China) and then counterstained them with Harris hematoxylin. All samples were imaged using an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) and compared with the vascular images obtained using SR imaging. For quantitative analysis, microvessel densities (MVDs) in hippocampal areas were calculated on a 2D plane of the images using Image Pro Plus 6.0. The MVD was defined as the number of microvessels divided by the total area analyzed.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for changes in morphological parameters after seizures. P < 0.05 denoted a statistically significant difference. Differences in blood vessel surface area, number of vascular segments, and number of vascular bifurcations were assessed using nonparametric tests, first by the Kruskal-Wallis test and then by the Mann-Whitney U-test. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Results

3D Morphology of Cerebral and Hippocampal Angioarchitecture

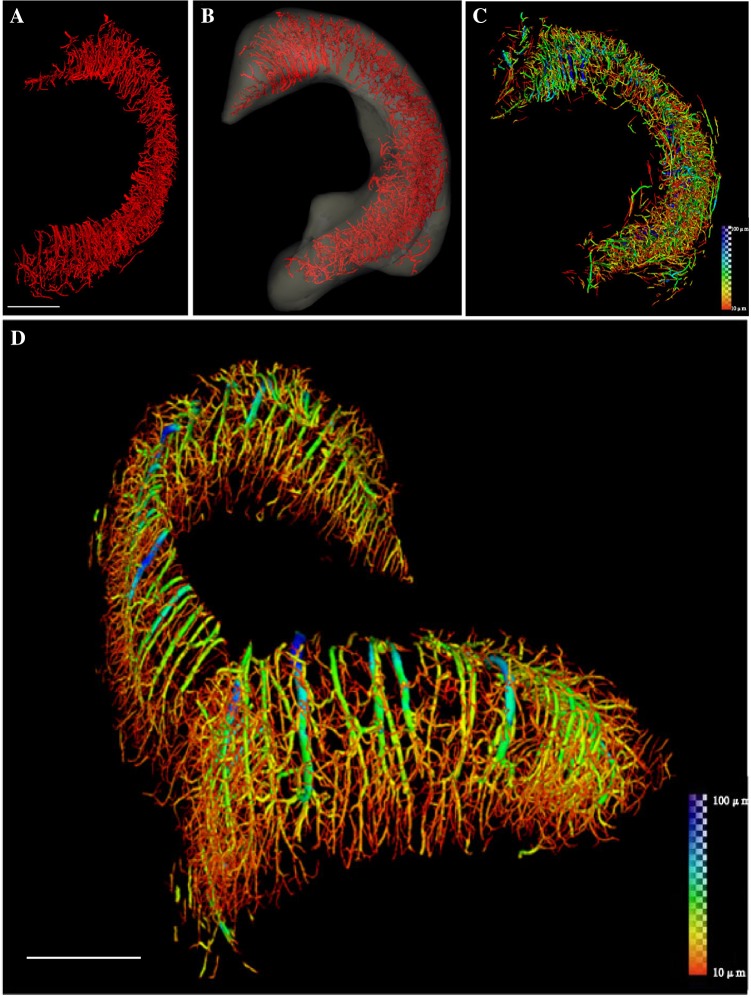

A high-throughput, high-brilliance, quasi-coherent, and high-purity synchrotron radiation source was used to display the spatial and temporal characteristics of rat hippocampal microvessels, including microvascular morphologies, shapes, branches, and nodes. Continuous pseudocolor changes depicted the distribution of vessel diameters, which ranged from 10 μm to 100 μm (Fig. 2). Using this information, the 3D microvascular network of the whole hippocampus was successfully reconstructed (Fig. 2D). Once this was done, the detailed 3D network of only the right hippocampus was extracted from the whole brain by SR-based ILPCI reconstruction. The spatial distribution of this section (the right hippocampus) was accurately outlined (Fig. 2A, B) and hippocampal vessel diameters were rendered to identify vessels with different diameters (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Reconstruction of the 3D angioarchitecture of the hippocampus in normal rat brain. A, B By SR-ILPCI reconstruction, the spatial structure distribution of the right hippocampal three-dimensional network was extracted from the whole brain (A) and accurately outlined (B) (scale bar, 600 μm). C Hippocampal vessel diameter rendering identifies the distribution of vessels with different diameters. D The original distribution of intracerebral vessels within the hippocampus with continuous pseudocolor changes depicting the distribution spectrum of vessel diameters, ranging from 10 μm to 100 μm (dark blue) (scale bar, 700 μm).

3D Visualization and Vascular Remodeling of Hippocampus after Epileptic Seizures

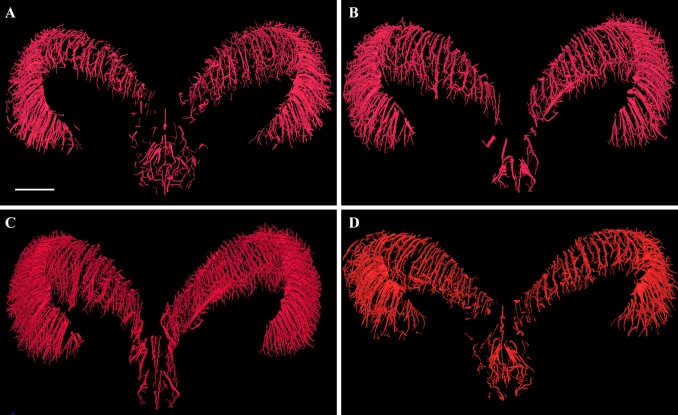

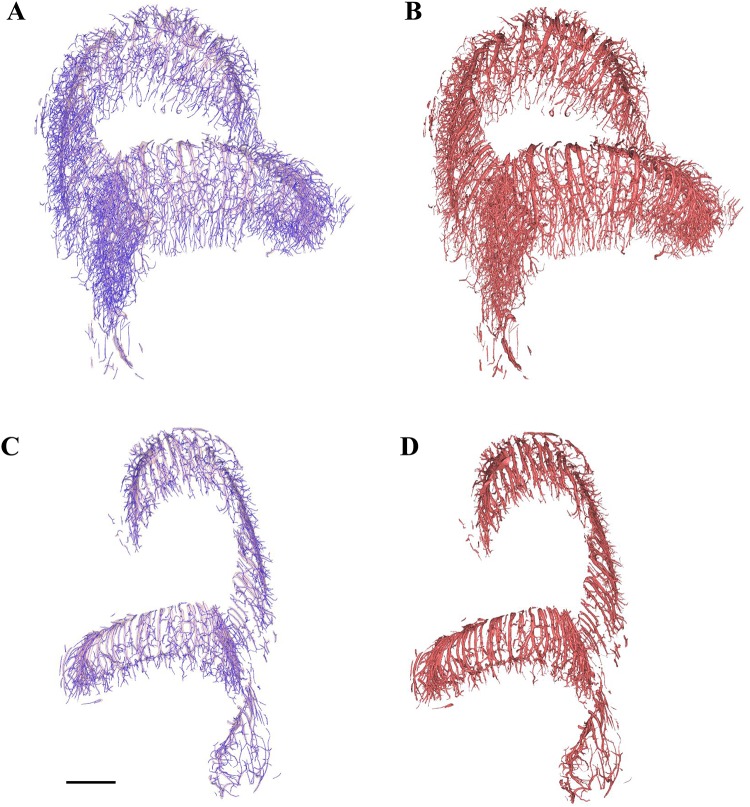

The 3D reconstructions of the experimental groups (days 1, 14, and 60) were compared with those of the control group. The reconstructions were performed using ILPCI to dynamically track angioarchitectural remodeling at different time points after the occurrence of epileptic seizures (Fig. 3). Compared to controls, the hippocampal angioarchitecture of the experimental groups showed remodeling in a dendritic pattern and increased density on day 1 after seizures. On day 14, the number of fine blood vessels with a twisted shape was significantly higher. On day 60, the total number of blood vessels decreased, and their distribution was loose and disordered, unlike the control group that had tightly-packed and well-organized blood vessels. On day 60, however, the diameters of the vessels varied widely and distinct differences were found (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Representative images of 3D microvasculature of hippocampus at different time points. A 3D image of vascular trees in rat hippocampus extracted from the whole brain in the control group (scale bar, 500 μm). B–D Images from day 1 (B), day 14 (C), and day 60 (D) after seizures.

Fig. 4.

Reconstructed 3D angioarchitecture on days 1 and 60 after epileptic seizures. A Day 1 hippocampal vascular centerlines (blue lines). B Day 1 reconstruction of hippocampal blood vessels. C Day 60 hippocampal vascular centerlines (blue lines). D Day 60 reconstruction of hippocampal blood vessels. Scale bar, 600 μm.

Quantitative Analysis of Hippocampal Angioarchitecture Following Policarpine-Induced Status Epilepticus

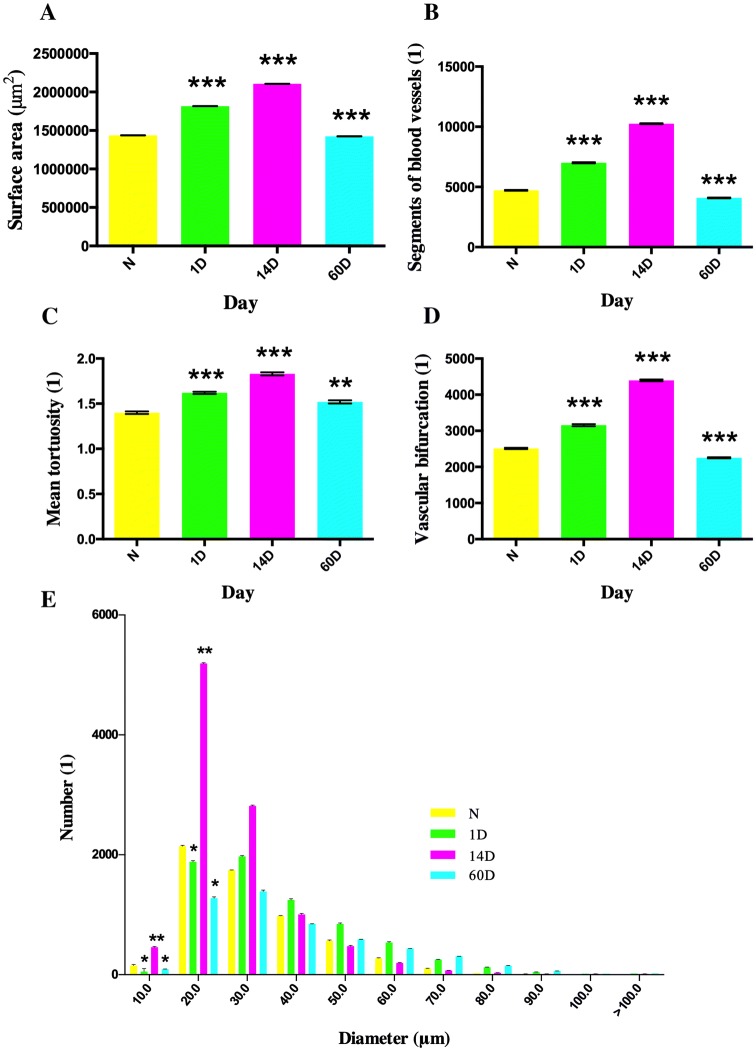

In order to objectively evaluate specific changes in the microvascular network after seizures, we analyzed the reconstructed hippocampal microvasculature based on the vascular tree module. For this, the surface area, blood vessel segments, mean tortuosity, vascular bifurcations, and diameter distribution were calculated and compared (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of vascular changes in hippocampus following PILO-induced SE. A–D The change of hippocampal microvessels in surface area (A), number of hippocampal microvascular segments (B), mean tortuosity (C), and number of bifurcations (D) with the course of disease. E The frequency distribution of blood vessels of different diameters. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs control group (N) at each time point; one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

The blood vessel surface area, number of vascular segments, and number of vascular bifurcations were measured in the control and experimental groups (days 1, 14, and 60). As the disease progressed, the surface area of blood vessels increased at days 1 and 14, while mice at day 60 showed a slight decline when compared to the control group (P < 0.05). The hippocampal microvascular segments and the number of bifurcations of hippocampal microvessels showed a similar trend, in that the days 1 and 14 groups had more and the day 60 group had fewer segments and bifurcations than the control group (P < 0.05).

To further examine the changes in microvasculature, we calculated the frequency distribution of blood vessels with different diameters. The changes at different time points occurred mainly in small blood vessels 10 μm and 20 μm in diameter, which showed an increasing trend over time compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5E). The changes that manifested on day 14 seemed more prominent than those on other days. There were no significant differences among the blood vessels of larger diameters.

In addition to changes in vascular surface area and diameter, vascular lesions can also affect vascular tortuosity in spatial changes. The mean tortuosity of a blood vessel was calculated based on the virtual vascular centerline. The value of this indicator increased with time, and the mean tortuosity in all three experimental groups was higher than that of the control group (Fig. 5C).

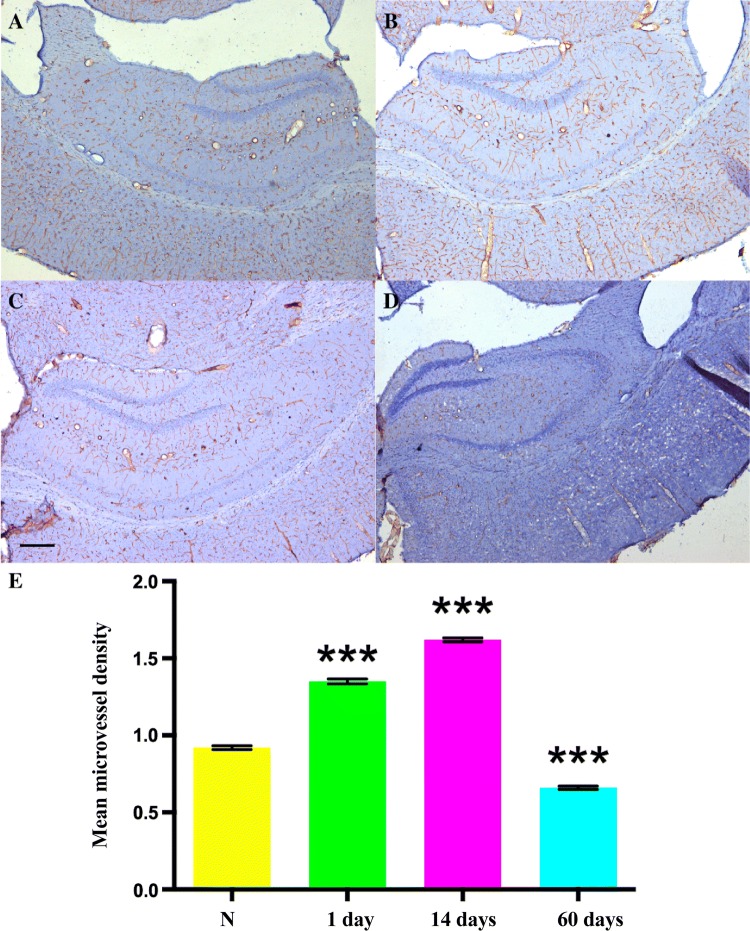

Overall, the number of vascular segments and mean tortuosity were higher on days 1 and 14 (P < 0.05), indicating an expansion of the hippocampal microvascular network. On the contrary, the number of segments and bifurcations was lower on day 60 (P < 0.05), suggesting a contraction of the hippocampal microvascular network. The surface area showed an increase on days 1 and 14, and a decline on day 60, which may account for the vessel constriction. Parallel quantifications using immunohistochemistry showed that the blood vessels displayed increased CD31 staining on day 1 and a significant decrease on day 60, consistent with the SR-ILPCI data (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Immunohistochemical staining of CD31 and quantitative analysis. A–D Representative images showing 5-fold magnification of histological staining for CD31 in the right hippocampus in the control (A), day 1 (B), day 14 (C), and day 60 (D) groups, revealing that the distribution of blood vessels in the hippocampus is not as rich as in cortex (scale bar, 200 μm). E Microvessel density in the hippocampal area (***P < 0.001 vs control (N)).

Discussion

The hippocampus is highly sensitive to ischemia, which is intimately associated with epilepsy. For instance, mesial TLE with hippocampal sclerosis is a common and well-documented phenomenon [4, 5, 66]. Recent research has shown that hippocampal vascularization changes that occur after seizures might be closely associated with the development of epilepsy [16, 18, 21, 22, 67]. To further investigate the role of hippocampal vascularization in the occurrence and progression of epilepsy, a more detailed understanding of angioarchitectural remodeling under normal physiological and pathological conditions is needed. Previous studies have confirmed that visualization techniques like histology and immunostaining have unavoidable limitations due to their invasiveness or lack of information on the spatial configuration of microvessels.

Other more modern technologies such as magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) [68] and CT angiography (CTA), including micro-CT, have their own shortcomings and cannot provide sufficiently detailed images of the microvasculature [69]. MRA requires long acquisition times and is not able to detect acute vascular changes [70], while CTA lacks the resolution to identify microvessels on a micron/submicron scale. Even though contrast-enhancing agents aid in delineating the 3D vasculature of whole brains, they may negatively affect the images [71]. MRI is advantageous for soft tissue visualization, but like CTA, is not sensitive enough to detect microvessels at micron/submicron levels [50]. These restrictions pose rather large limitations if one wishes to study the relationship between hippocampal vascularization and epilepsy.

SR-based ILPCI provides direct and straightforward visualization of microvascular networks in the brain. SR X-rays are different from traditional X-rays as the electrons come from the curvilinear motion of the sample in a magnetic field and the change of direction can often approach the speed of light. The magnetic field in a storage ring can therefore control the direction of electrons, giving SR X-rays high directivity, small divergence, and variable polarization. Such features confer upon SR X-rays the capability of providing more detailed information about microvessel shape and spatial organization, helping us better understand the changes in microvascular networks during epilepsy [72]. In this study, we used ILPCI and the SSRF BL13W1 beamline with a pixel size of 5.2 μm to obtain high-resolution images of rat brain vasculature and hippocampal microvasculature. No contrast-enhancing agents were added at any point in the process and therefore this method provides reliable depictions of microvessel configuration through a boundary-enhancement effect.

The 3D angioarchitecture reconstructed in this study demonstrated hippocampal microvascular remodeling alongside the progression of epilepsy. Such high resolution, 3D visualization facilitated further exploration of hippocampal microvascular angiogenesis, including the analysis of microvascular surface area, vascular tortuosity, and diameter distribution. The hippocampal microvasculature in rats suffering from lithium-PILO-induced epilepsy showed dramatic changes in overall organization. There is now a growing body of evidence that the density of blood vessels is increased in the sclerotic hippocampal regions of patients with TLE [23, 73]. Aside from this, it has been suggested that collagen-IV [23] and X-box binding protein l splicing [74] positively regulate cell proliferation and angiogenesis, pointing to possible molecular mechanisms underlying hippocampal angiogenesis during epilepsy. In our study, the 3D images generated showed that the surface area of blood vessels, number of hippocampal microvascular segments, and number of bifurcations of hippocampal microvessels were higher in SE-induced rats on days 1 and 14. Research by Alonso-Nanclares et al. showed that these new blood vessels are actually atrophic vascular structures with reduced or even absent lumens, often filled with the processes of reactive astrocytes [55]. Furthermore, one study has shown that angiogenesis and microglial activation are linked to epilepsy-induced neuronal death in the cerebral cortex [75]. It has been suggested that the newly-formed microvasculature is soon filled with reactive astrocytes and atrophy sets at a later stage. The atrophy might in fact be triggered by the act of being filled with astrocytes.

Our results showed that, during the development of epilepsy, the angioarchitecture of the hippocampus undergoes some remodeling, and eventually, vessel constriction. Hippocampal vascularization and angiogenesis in SE may be facilitated by bone marrow-derived cells, which can penetrate through parenchyma and help to build new cerebral vasculature in a time-dependent manner [68].

Some studies have proposed that angiogenesis increases the permeability of the BBB, which may directly induce epilepsy [76, 77]. In such scenarios, hippocampal angiogenesis may be the result of an unfortunate positive feedback loop, providing a potential intervention point and a treatment strategy for epilepsy. It has been reported that drugs targeting specific vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 2 pathways help to reduce epileptogenicity [77]. The progression of epilepsy can also be accelerated by inflammatory factors and neurotoxic amino-acids that pass through the injured BBB [78]. Therefore, a combination of drugs targeting angiogenesis, which also aid in clearing toxic cellular by-products, along with traditional anti-epileptic drugs may offer a new strategy for the treatment of epilepsy. Our findings provide visual evidence that can be used to test these hypotheses and also set in place methods to further study vascular changes in the brain.

The SR-ILPCI technique is a novel and reliable method for direct visualization of hippocampal microvascular networks during the progression of epilepsy. Despite its many advantages, there are still some limitations to the clinical application of this method. On the one hand, synchrotron radiation devices are excessively large, making the development of small-scale diagnostic instruments a challenge. On the other hand, SR-based ILPCI technology can currently only image small-volume samples due to the narrow light spot and high-resolution detectors, which also require small fields of view. Consequently, expanding the visual fields is an obstacle that needs to be overcome. Moreover, the radiation required for high-resolution imaging may damage biological tissues, even though efforts have been made to reduce the exposure time and radiation dose. Finally, the complete dehydration requirement for samples can potentially introduce small deformations, which is a common problem faced by any ex vivo 3D visualization of brain vasculature. The acceptable extent of deformation and feasibility of existing methods have been discussed in detail in our previous work [49]. In spite of these constraints, our data demonstrated that original morphological features are retained better using this method than with other invasive processes. In general, the method we used broadens the scope of study of cerebrovascular microstructural changes, and it does so better than existing technologies. While we still need to develop more accurate and efficient imaging technology in the future, we believe that SR-based techniques will provide a valuable platform to explore microvascular plasticity during epilepsy. This will ultimately help us understand the underlying pathogenic mechanisms of epilepsy in depth.

Conclusions

The 3D configuration of microvascular networks in the rat hippocampus under normal and seizure conditions was reconstructed using SR-based ILPCI and without any contrast-enhancing agents. This allowed microvessels to be distinguished at ultra-high resolution. Remodeling of focal brain microvasculature plays a vital role in the pathogenesis and development of epilepsy, and therefore SR-based ILPCI opens new avenues for the 3D imaging of brain vasculature and facilitates quantitative analysis of vascular networks in diverse pathologies. SR-based PCI holds considerable promise for the visualization of subtle structural details in microvessels, without the use of contrast-enhancing agents. Coupled with the further advancements in microtomography, future investigations using SR imaging will provide auxiliary diagnoses in neurovascular disorders and efficient evaluation of therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgements

This work was completed at the BL13W1 beamline of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) in China and was supported by Key Research Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016YFC0904400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81501025 & 81671299), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2016JJ3174), and the Science and Technology Department Funds of Hunan Province Key Project (2016JC2057). We would like to thank Prof. Tiqiao Xiao and other staff at the BL13W1 station of SSRF for their kind assistance during the experiments.

Footnotes

Pan Gu, Zi-Hao Xu and Yu-Ze Cao have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Bo Xiao, Email: csuxiaobo123456@163.com.

Meng-Qi Zhang, Email: zhangmengqi8912@163.com.

References

- 1.Aronica E, Muhlebner A. Neuropathology of epilepsy. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;145:193–216. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-802395-2.00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher RS, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, Elger C, Genton P, Lee P, et al. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE) Epilepsia. 2005;46:470–472. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Truccolo W, Donoghue JA, Hochberg LR, Eskandar EN, Madsen JR, Anderson WS, et al. Single-neuron dynamics in human focal epilepsy. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:635–641. doi: 10.1038/nn.2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuele SU, Luders HO. Intractable epilepsy: management and therapeutic alternatives. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:514–524. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70108-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semah F, Picot MC, Adam C, Broglin D, Arzimanoglou A, Bazin B, et al. Is the underlying cause of epilepsy a major prognostic factor for recurrence? Neurology. 1998;51:1256–1262. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu XX, Luo JH. Mutations of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits in epilepsy. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34:549–565. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0191-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei F, Yan LM, Su T, He N, Lin ZJ, Wang J, et al. Ion channel genes and epilepsy: functional alteration, pathogenic potential, and mechanism of epilepsy. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:455–477. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0134-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Reuck J, Nagy E, Van Maele G. Seizures and epilepsy in patients with lacunar strokes. J Neurol Sci. 2007;263:75–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maxwell H, Hanby M, Parkes LM, Gibson LM, Coutinho C, Emsley HC. Prevalence and subtypes of radiological cerebrovascular disease in late-onset isolated seizures and epilepsy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naik P, Cucullo L. In vitro blood-brain barrier models: current and perspective technologies. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101:1337–1354. doi: 10.1002/jps.23022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camidge DR, Pao W, Sequist LV. Acquired resistance to TKIs in solid tumours: learning from lung cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:473–481. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morin-Brureau M, De Bock F, Lerner-Natoli M. Organotypic brain slices: a model to study the neurovascular unit micro-environment in epilepsies. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2013;10:11. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer S, Wobben M, Marti HH, Renz D, Schaper W. Hypoxia-induced hyperpermeability in brain microvessel endothelial cells involves VEGF-mediated changes in the expression of zonula occludens-1. Microvasc Res. 2002;63:70–80. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2001.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rochfort KD, Cummins PM. Cytokine-mediated dysregulation of zonula occludens-1 properties in human brain microvascular endothelium. Microvasc Res. 2015;100:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchi N, Lerner-Natoli M. Cerebrovascular remodeling and epilepsy. Neuroscientist. 2013;19:304–312. doi: 10.1177/1073858412462747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milesi S, Boussadia B, Plaud C, Catteau M, Rousset MC, De Bock F, et al. Redistribution of PDGFRbeta cells and NG2DsRed pericytes at the cerebrovasculature after status epilepticus. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;71:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klement W, Garbelli R, Zub E, Rossini L, Tassi L, Girard B, et al. Seizure progression and inflammatory mediators promote pericytosis and pericyte-microglia clustering at the cerebrovasculature. Neurobiol Dis. 2018;113:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gales JM, Prayson RA. Chronic inflammation in refractory hippocampal sclerosis-related temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;30:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Z, You Z, Li M, Pang L, Cheng J, Wang L. Protective effect of resveratrol on the brain in a rat model of epilepsy. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:273–280. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0097-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ndode-Ekane XE, Hayward N, Grohn O, Pitkanen A. Vascular changes in epilepsy: functional consequences and association with network plasticity in pilocarpine-induced experimental epilepsy. Neuroscience. 2010;166:312–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicoletti JN, Shah SK, McCloskey DP, Goodman JH, Elkady A, Atassi H, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is up-regulated after status epilepticus and protects against seizure-induced neuronal loss in hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2008;151:232–241. doi: 10.1061/j.neuroscience.2007.09.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Y, Zhang Y, Guo Z, Yin H, Zeng K, Wang L, et al. Increased placental growth factor in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with epilepsy. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:665–670. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0646-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rigau V, Morin M, Rousset MC, de Bock F, Lebrun A, Coubes P, et al. Angiogenesis is associated with blood-brain barrier permeability in temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2007;130:1942–1956. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benini R, Roth R, Khoja Z, Avoli M, Wintermark P. Does angiogenesis play a role in the establishment of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy? Int J Dev Neurosci. 2016;49:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Vliet EA, Otte WM, Wadman WJ, Aronica E, Kooij G, de Vries HE, et al. Blood-brain barrier leakage after status epilepticus in rapamycin-treated rats II: Potential mechanisms. Epilepsia. 2016;57:70–78. doi: 10.1111/epi.13245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnett A, Audrain S, McAndrews MP. Applications of resting-state functional MR imaging to epilepsy. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2017;27:697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russo E, Leo A, Scicchitano F, Donato A, Ferlazzo E, Gasparini S, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease predisposes to temporal lobe epilepsy in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Brain Res Bull. 2017;130:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao W, Zhang J, Song Y, Sun L, Zheng M, Yin H, et al. Irreversible fatal contrast-induced encephalopathy: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2019;19:46. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sengupta S, Fritz FJ, Harms RL, Hildebrand S, Tse DHY, Poser BA, et al. High resolution anatomical and quantitative MRI of the entire human occipital lobe ex vivo at 9.4T. Neuroimage 2018, 168: 162–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Federau C, Gallichan D. Motion-correction enabled ultra-high resolution in-vivo 7T-MRI of the brain. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung SC, Kim HS, Choi CG, Kim SJ, Lee DH, Suh DC, et al. Quantitative analysis using high-resolution 3T MRI in acute intracranial artery dissection. J Neuroimaging. 2016;26:612–617. doi: 10.1111/jon.12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li P, Yu X, Griffin J, Levine JM, Jim J. High-resolution MRI of spinal cords by compressive sensing parallel imaging. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2015;2015:4266–4269. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2015.7319337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang M, Peng G, Sun D, Xie Y, Xia J, Long H, et al. Synchrotron radiation imaging is a powerful tool to image brain microvasculature. Med Phys. 2014;41:031907. doi: 10.1118/1.4865784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulz G, Weitkamp T, Zanette I, Pfeiffer F, Beckmann F, David C, et al. High-resolution tomographic imaging of a human cerebellum: comparison of absorption and grating-based phase contrast. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7:1665–1676. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis R. Medical applications of synchrotron radiation X-rays. Phys Med Biol. 1997;42:1213–1243. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/42/7/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eggl E, Schleede S, Bech M, Achterhold K, Loewen R, Ruth RD, et al. X-ray phase-contrast tomography with a compact laser-driven synchrotron source. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:5567–5572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500938112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoshino M, Uesugi K, Tsukube T, Yagi N. Quantitative and dynamic measurements of biological fresh samples with X-ray phase contrast tomography. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2014;21:1347–1357. doi: 10.1107/S1600577514018128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou SA, Brahme A. Development of phase-contrast X-ray imaging techniques and potential medical applications. Phys Med. 2008;24:129–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Endrizzi M. X-ray phase-contrast imaging. Nucl Inst Methods Phys Res A. 2018;878:88–98. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Snigirev A, Snigireva I, Lyubomirskiy M, Kohn V, Yunkin V, Kuznetsov S. X-ray multilens interferometer based on Si refractive lenses. Opt Express. 2014;22:25842–25852. doi: 10.1364/OE.22.025842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chapman D, Thomlinson W, Johnston RE, Washburn D, Pisano E, Gmur N, et al. Diffraction enhanced x-ray imaging. Phys Med Biol. 1997;42:2015–2025. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/42/11/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang X, Yang XR, Chen Y, Li HQ, Li RM, Yuan QX, et al. Visualising liver fibrosis by phase-contrast X-ray imaging in common bile duct ligated mice. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:417–423. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2630-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sztrokay A, Herzen J, Auweter SD, Liebhardt S, Mayr D, Willner M, et al. Assessment of grating-based X-ray phase-contrast CT for differentiation of invasive ductal carcinoma and ductal carcinoma in situ in an experimental ex vivo set-up. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:381–387. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lundstrom U, Larsson DH, Burvall A, Scott L, Westermark UK, Wilhelm M, et al. X-ray phase-contrast CO(2) angiography for sub-10 mum vessel imaging. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57:7431–7441. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/22/7431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bravin A, Coan P, Suortti P. X-ray phase-contrast imaging: from pre-clinical applications towards clinics. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58:R1–35. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/1/R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayo SC, Stevenson AW, Wilkins SW. In-line phase-contrast X-ray imaging and tomography for materials science. Materials (Basel) 2012;5:937–965. doi: 10.3390/ma5050937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Debatin JF, Spritzer CE, Grist TM, Beam C, Svetkey LP, Newman GE, et al. Imaging of the renal arteries: value of MR angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:981–990. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.5.1927823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao Y, Liao S, Zeng H, Ni S, Tintani F, Hao Y, et al. 3D characterization of morphological changes in the intervertebral disc and endplate during aging: A propagation phase contrast synchrotron micro-tomography study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43094. doi: 10.1038/srep43094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang MQ, Zhou L, Deng QF, Xie YY, Xiao TQ, Cao YZ, et al. Ultra-high-resolution 3D digitalized imaging of the cerebral angioarchitecture in rats using synchrotron radiation. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14982. doi: 10.1038/srep14982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang MQ, Sun DN, Xie YY, Peng GY, Xia J, Long HY, et al. Three-dimensional visualization of rat brain microvasculature following permanent focal ischaemia by synchrotron radiation. Br J Radiol. 2014;87:20130670. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20130670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li B, Zhang Y, Wu W, Du G, Cai L, Shi H, et al. Neovascularization of hepatocellular carcinoma in a nude mouse orthotopic liver cancer model: a morphological study using X-ray in-line phase-contrast imaging. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:73. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3073-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu J, Li P, Yin X, Wu T, Cao Y, Yang Z, et al. Nondestructive imaging of the internal microstructure of vessels and nerve fibers in rat spinal cord using phase-contrast synchrotron radiation microtomography. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2017;24:482–489. doi: 10.1107/S1600577517000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fratini M, Bukreeva I, Campi G, Brun F, Tromba G, Modregger P, et al. Simultaneous submicrometric 3D imaging of the micro-vascular network and the neuronal system in a mouse spinal cord. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8514. doi: 10.1038/srep08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Studer F, Serduc R, Pouyatos B, Chabrol T, Brauer-Krisch E, Donzelli M, et al. Synchrotron X-ray microbeams: A promising tool for drug-resistant epilepsy treatment. Phys Med. 2015;31:607–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pouyatos B, Nemoz C, Chabrol T, Potez M, Brauer E, Renaud L, et al. Synchrotron X-ray microtransections: a non invasive approach for epileptic seizures arising from eloquent cortical areas. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27250. doi: 10.1038/srep27250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pacile S, Baran P, Dullin C, Dimmock M, Lockie D, Missbach-Guntner J, et al. Advantages of breast cancer visualization and characterization using synchrotron radiation phase-contrast tomography. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2018;25(Pt 5):1460–1466. doi: 10.1107/S1600577518010172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tavakoli Taba S, Baran P, Lewis S, Heard R, Pacile S, Nesterets YI, et al. Toward improving breast cancer imaging: radiological assessment of propagation-based phase-contrast CT technology. Acad Radiol. 2019;26:e79–e89. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Honchar MP, Olney JW, Sherman WR. Systemic cholinergic agents induce seizures and brain damage in lithium-treated rats. Science. 1983;220:323–325. doi: 10.1126/science.6301005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eslami SM, Ghasemi M, Bahremand T, Momeny M, Gholami M, Sharifzadeh M, et al. Involvement of nitrergic system in anticonvulsant effect of zolpidem in lithium-pilocarpine induced status epilepticus: Evaluation of iNOS and COX-2 genes expression. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;815:454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu T, Ido K, Osada Y, Kotani S, Tamaoka A, Hanada T. The neuroprotective effect of perampanel in lithium-pilocarpine rat seizure model. Epilepsy Res. 2017;137:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu Q, Li Y, Shu Y, Feng L, Zhou L, Yue ZW, et al. NDEL1 was decreased in the CA3 region but increased in the hippocampal blood vessel network during the spontaneous seizure period after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Neuroscience. 2014;268:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen RC, Dreossi D, Mancini L, Menk R, Rigon L, Xiao TQ, et al. PITRE: software for phase-sensitive X-ray image processing and tomography reconstruction. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2012;19:836–845. doi: 10.1107/S0909049512029731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luo Y, Yin X, Shi S, Ren X, Zhang H, Wang Z, et al. Non-destructive 3D microtomography of cerebral angioarchitecture changes following ischemic stroke in rats using synchrotron radiation. Front Neuroanat. 2019;13:5. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2019.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang G, Kitslaar P, Frenay M, Broersen A, Boogers MJ, Bax JJ, et al. Automatic centerline extraction of coronary arteries in coronary computed tomographic angiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;28:921–933. doi: 10.1007/s10554-011-9894-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chatzikonstantinou A. Epilepsy and the hippocampus. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2014;34:121–142. doi: 10.1159/000356435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Romariz SA, Garcia Kde O, Paiva Dde S, Bittencourt S, Covolan L, Mello LE, et al. Participation of bone marrow-derived cells in hippocampal vascularization after status epilepticus. Seizure. 2014;23:386–389. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamamoto H, Iku S, Adachi Y, Imsumran A, Taniguchi H, Nosho K, et al. Association of trypsin expression with tumour progression and matrilysin expression in human colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 2003;199:176–184. doi: 10.1002/path.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hu JZ, Wu TD, Zeng L, Liu HQ, He Y, Du GH, et al. Visualization of microvasculature by x-ray in-line phase contrast imaging in rat spinal cord. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57:N55–63. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/5/N55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Figueiredo G, Brockmann C, Boll H, Heilmann M, Schambach SJ, Fiebig T, et al. Comparison of digital subtraction angiography, micro-computed tomography angiography and magnetic resonance angiography in the assessment of the cerebrovascular system in live mice. Clin Neuroradiol. 2012;22:21–28. doi: 10.1007/s00062-011-0113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu X, Zhao J, Sun J, Gu X, Xiao T, Liu P, et al. Lung cancer and angiogenesis imaging using synchrotron radiation. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:2399–2409. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/8/017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Margaritondo G, Meuli R. Synchrotron radiation in radiology: novel X-ray sources. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2633–2641. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-2073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alonso-Nanclares L, DeFelipe J. Alterations of the microvascular network in the sclerotic hippocampus of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;38:48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shi S, Tang M, Li H, Ding H, Lu Y, Gao L, et al. X-box binding protein l splicing attenuates brain microvascular endothelial cell damage induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation through the activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B, extracellular signal-regulated kinases, and hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha/vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:9316–9327. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sakurai M, Morita T, Takeuchi T, Shimada A. Relationship of angiogenesis and microglial activation to seizure-induced neuronal death in the cerebral cortex of Shetland Sheepdogs with familial epilepsy. Am J Vet Res. 2013;74:763–770. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.74.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Myczek K, Yeung ST, Castello N, Baglietto-Vargas D, LaFerla FM. Hippocampal adaptive response following extensive neuronal loss in an inducible transgenic mouse model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morin-Brureau M, Rigau V, Lerner-Natoli M. Why and how to target angiogenesis in focal epilepsies. Epilepsia. 2012;53(Suppl 6):64–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Winkler EA, Bell RD, Zlokovic BV. Central nervous system pericytes in health and disease. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1398–1405. doi: 10.1038/nn.2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]