Abstract

Objective:

Detecting brain abnormalities in clinical high-risk (CHR) populations, prior to the onset of psychosis, is important for tracking pathological pathways, and for identifying possible intervention strategies that may impede or prevent the onset of psychotic disorders. Co-occurring cellular and extracellular white matter alterations have previously been implicated following a first psychotic episode. The present study investigates whether or not cellular and extracellular alterations are already present in a predominantly medication-naïve cohort of CHR subjects experiencing attenuated psychotic symptoms.

Method:

Fifty CHR individuals, of whom 40 were never medicated, were compared with 50 healthy controls, group matched for age, gender and parental socio-economic status. 3T multi-shell diffusion MRI data were obtained to estimate free-water imaging white matter measures, including fractional anisotropy of cellular tissue (FAT) and the volume fraction of extracellular free-water (FW).

Results:

Significantly lower FAT (F(1,95)=5.556, p=0.020) was observed in CHR subjects, compared with healthy controls, but no statistically significant FW alterations (F(1,95)=2.243, p=0.137) were observed between groups. Additionally, lower FAT in CHR subjects was significantly associated with a decline in Global Assessment of Functioning (r=−0.385, p=0.006).

Conclusions:

Cellular but not extracellular alterations characterized the CHR subjects, especially in those who experienced a decline in functioning. These cellular changes suggest an early deficit that possibly reflects a predisposition to develop attenuated psychotic symptoms. In contrast, extracellular alterations were not observed in this CHR population, suggesting that previously reported extracellular abnormalities may reflect an acute response to psychosis, which plays a more prominent role closer to or at onset of psychosis.

Keywords: Clinical high-risk, Diffusion tensor imaging, Free water, White matter, Neurodevelopment

Schizophrenia is a severe psychiatric disorder that emerges most commonly in late adolescence and early adulthood, affecting approximately 1% of the population (1). Recent studies have focused on detection and treatment intervention in the early stages of psychotic illness (2), especially during the clinical high-risk (CHR) phase, before a full-blown disorder is present (3, 4). Because psychotic symptoms, cognitive dysfunctions, and disturbances in social functions may all evolve in the CHR phase (5–8), investigating brain alterations in CHR could potentially shed light on their underlying mechanisms.

Studies in the last two decades, and especially those applying diffusion MRI (dMRI) techniques, strongly suggest white matter abnormalities in schizophrenia, where disrupted cortico-cortical connections may play a key role in both clinical symptoms and cognitive dysfunctions (9–13). Most studies apply diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) (14, 15) to estimate fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure sensitive to the arrangement and microstructure of white matter, often used to assess white matter integrity (9, 12, 13, 16). Lower FA, however, may be caused by different factors including axon diameter alterations, alterations in myelin sheath, increased extracellular volume fraction, and/or alterations in the organization of axonal fibers (17–23). Consequently, FA provides a non-specific and less than optimal estimate of white matter integrity (24), making it hard to relate FA changes with a specific underlying pathology. In addition, meta-analysis shows that FA alterations may be affected by the stage of illness and by exposure to antipsychotic medications (25). Thus, additional methodological advances and a careful selection of study populations are required to determine the source(s) of white matter alterations and their association with illness progression.

One way to increase FA specificity is to correct for partial volume effects with extracellular water. For example, free-water imaging analysis (19, 23, 26) uses two compartments to separately model diffusion properties of brain tissue and those of surrounding free water, which can only be found in the extracellular space (19). Tissue-FA (FAT), which is more specific to white matter cellular alterations than conventional FA measures, is derived from the tissue compartment, following the elimination of the free-water contribution. In addition, this model estimates the fractional volume of the free-water compartment (FW), which is affected by processes that change the extracellular space, such as atrophy and neuroinflammation (18, 27). FW maps can also be estimated using other dMRI techniques [e.g., (17, 28, 29)], and across methods show high signal in CSF filled cavities and lower albeit non-zero signal throughout the white matter.

Previous free-water imaging studies comparing patients following their first psychotic episode with healthy controls have shown widespread higher FW with limited focal lower FAT in frontal lobe regions of patients (18, 30). In chronic patients, the reverse has been noted, i.e., a greater extent of significantly lower FAT with less extensive significantly higher FW (27, 30). These results suggest that white matter abnormalities may be explained by co-occurring alterations: extracellular free-water alterations, measured by FW, and microstructural cellular alterations, measured by FAT. The higher FW may thus reflect an acute brain response to psychosis, which is less pronounced in chronic stages, while lower FAT may reflect preexisting neurodevelopmental abnormalities and/or a continuous process of accumulating cellular damage.

An important step towards understanding the source of these different white matter alterations is to investigate CHR to determine whether or not extracellular and cellular alterations are present before the onset of psychosis, and if so to what extent. There are currently only a limited number of dMRI studies in CHR subjects, most of which are based on DTI, and most are with a small sample size. Two separate white matter fiber-tracking studies report no significant differences between CHR subjects and healthy controls (31, 32). In contrast, three other studies show limited frontal regions with lower FA (33–35). In two additional tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) studies (36, 37), extensive regions with lower FA were observed in the corpus callosum, the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), the internal capsule, and in the corona radiata (CR) of patients. In one study that applied free-water imaging on a CHR cohort, group differences were found in FAT in fibers connecting the salience network (38), but FW has not been tested. These studies, taken together, suggest that while white matter alterations are likely present in CHR subjects, they are inconsistent, may not have a distinct location, and they are more subtle than those evinced in schizophrenia.

In the current study, we go beyond previous studies by performing a dMRI study on a large CHR population that was recruited in China, where most patients were naïve to psychotropic medications. Furthermore, we use free-water analysis to separately evaluate the extent and putative roles of extracellular and tissue-related microstructural white matter. Based on our first-episode study, we predicted that both types of alterations (higher FW and lower FAT) would be present in the CHR stage. In addition, based on the extent of the alterations, we aimed to identify which of these processes, extracellular or cellular changes, are more related to attenuated symptoms, prior to onset of psychosis.

METHODS

Participants

The ShangHai At Risk for Psychosis (SHARP) program of Shanghai Mental Health Center (SMHC) recruited help-seeking CHR subjects from their first outpatient assessment. A 2-year conversion rate to psychosis of 29.1% was previously observed in this predominantly medication naïve Chinese population (39). All subjects met criteria for CHR (Table 1), defined by the Chinese version of the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS) and the Scale of Prodromal Syndromes (SOPS) (40), administered by a senior psychiatrist (39, 41). Intervals between recruitment and MRI scan were 2.5 (SD=7.7) days. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) was assessed at time of recruitment, and retrospectively for the prior 12 months. Functional decline (per SIPS definition) was calculated as the drop in the current Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score compared to the patient’s highest GAF score in the prior 12 months (39, 42). Conversion to psychosis was assessed at least one year following the baseline assessment with the criteria of POPS (Presence of Psychotic Symptoms in SIPS) (43, 44). The first fifty CHR subjects who passed imaging quality control evaluation (see below) were included in this study.

Table 1.

Number of subjects meeting the different criteria for clinical high risk and experiencing symptoms.

| Criteria / Symptoms | # of CHR |

|---|---|

| Attenuated positive symptom syndrome (APSS) | 45 |

| Brief Intermittent Psychotic Syndrome (BIPS) | 2 |

| Genetic Risk and Deterioration Syndrome (GRDS) | 1 |

| APSS+GRDS | 2 |

| P1, unusual thought content > 2 | 41 |

| P2, suspiciousness > 2 | 42 |

| P3, grandiose ideas > 2 | 0 |

| P4, perceptual abnormalities > 2 | 22 |

| P5, disorganized communication | 2 |

CHR: Clinical high risk for psychosis

Healthy controls (HCs) were recruited through online advertisements, and fifty healthy controls that passed imaging quality control and were matched in age and gender to the CHR sample (Table 2) were included in the present study. Exclusion criteria at study entry for all participants included head injury with loss of consciousness of any duration, and any history of substance use, neurological disease, severe somatic diseases, IQ < 70, and/or dementia. HCs were additionally excluded if they met criteria for a psychotic disorder or a CHR syndrome (determined by SIPS) or any other mental disorder defined by DSM-IV. All subjects were right-handed by self-report.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects

| CHR | HCs | Statistical Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | 50 | 50 | - |

| Gender (female/male) | 20/30 | 20/30 | χ2(1) = 0.00, p=1.00 |

| Age range (years) | 14–32 | 14–31 | - |

| Age (years) | 19.7±4.6 | 19.2±3.9 | t(98)=0.62, p=0.54 |

| Education (years) | 10.5±2.4 | 11.2±2.3 | t(98)=−1.35, p=0.18 |

| Parental Education – Father | 10.2±3.9 | 10.3±4.2 | t(90)=−0.17, p=0.87 |

| Parental Education – Mother | 9.5±4.4 | 10.3±3.8 | t(90)=−0.88, p-0.38 |

| Average Motion (mm) | 1.0960±0.1888 | 1.0997±0.1830 | t(98)=−0.10, p=0.92 |

| Handedness (right/left) | 50/0 | 50/0 | - |

| Duration of symptoms (months) | 6.5±6.2 | - | - |

| SOPS-positive | 9.0±3.2 | - | - |

| SOPS-negative | 12.7±6.4 | - | - |

| SOPS-disorganization | 6.7±2.9 | - | - |

| SOPS-general | 9.1±3.2 | - | - |

| Highest GAF | 76.8±6.1 | - | - |

| GAF current | 51.3±7.0 | - | - |

| Antipsychotics | 10(20%) | - | - |

CHR: Clinical high risk for psychosis; HCs: healthy controls; SOPS: the Scale of Prodromal Syndromes; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning.

The study protocol and consent form were reviewed and approved by the local Ethics Committee at SMHC, China and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, USA. Written informed consent was obtained from each individual.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Data Acquisition

All subjects underwent MRI scans at SMHC using a 3 Tesla Siemens scanner (Verio, Siemens, Munich, Germany) with a 32-channel head coil. Multi-shell dMRI was acquired with 30 gradient directions at b=1000s/mm2, 6 at b=500s/mm2, 3 at b=200s/mm2, and 5 interleaved b0 images. An additional 30 gradient directions at b=3000s/mm2 were collected for tractography studies, however the latter shell was omitted from calculations so as to circumvent non-Gaussian effects. The sequence had 70 contiguous axial slices, 256mm field-of-view, 2mm isotropic voxels, repetition-time of 15800ms, and echo-time of 109ms. Acquisition time was 20:17 minutes, with 6/8 phase partial Fourier, and GeneRalized Autocalibrating Partial Parallel Acquisition (GRAPPA) with acceleration factor 2. Scanning parameters and acquisitions at SMHC were supervised by members of the Psychiatry Neuroimaging Laboratory (PNL) at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (http://pnl.bwh.harvard.edu), with visits to Shanghai and ongoing communication with the chief technical scientist (YT) at Shanghai.

Image Analysis

All scans included in the study passed quality control, which included visual inspection of the raw data, as well as visual inspection of the output images by trained raters at the PNL. Three CHR cases that had incomplete brain coverage, and 10 CHR cases that had severe image artifacts (e.g., multiple dropped signals, blurring or ghosting) were excluded from the study. One matching HC was excluded due to severe image artifacts. Additional inspection was made on the output images where no unusual output images were identified. Thus, in total, 63 CHR cases and 51 matching HC cases were considered before selecting the 50 CHR and 50 HC cases that were included in the study. Minor head motion and eddy current distortions were corrected using low-level registration functions (e.g., flirt and fnirt) from FSL version 5.0.4 (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) as part of the PNL’s analysis pipeline (https://github.com/pnlbwh/pnlutil). A motion parameter (the between-volume displacement averaged across all volumes) was estimated from these transformations and gradient orientations were corrected for the rotation component. DWI masks were manually edited in 3D Slicer (www.slicer.org). FA maps were generated by a non-linear fit estimation of diffusion tensors. We used TBSS to register all subjects to the FSL provided MNI template, and to generate a white matter skeleton from the FA maps, which is less susceptible to between subject mis-registration and is focused on the center of fibers, where less partial volume is expected (45, 46).

The free-water analysis is described in detail elsewhere (18, 19, 27). Briefly, water diffusion within each voxel is modeled using two compartments (19): an isotropic free-water compartment with the diffusion coefficient of free-water in body temperature (3×10−3mm2/s), and a second compartment (the tissue compartment) modeled by a diffusion tensor, accounting for water molecules that are not free to diffuse since they are hindered or restricted by tissue components such as membranes. Measures obtained from this model, using a non-linear and regularized fit (19), are the free-water compartment fraction (FW), and the tissue-FA (FAT), calculated from the tissue compartment’s tensor. For completeness, additional parameters were calculated from the tissue compartment’s tensor, namely, radial diffusivity (RDT) and axial diffusivity (ADT). In contrast to most previous publications, here the model was estimated from multi-shell diffusion imaging data, where the model fit becomes more stable and robust compared with single-shell data that is typically used in DTI studies (23, 47). FW, FAT, RDT and ADT maps were calculated for each subject, and then projected onto the TBSS skeleton for statistical analyses.

Statistical Analysis

For the first level of analysis, FW and FAT values were averaged across the white matter skeleton, in order to identify differences between groups that may not necessarily be location dependent. Linear regression models were constructed to compare CHR with HC, where the average diffusivity measure (FW or FAT) was the dependent variable, and group (HC or CHR), age, gender, and motion were predictor variables. Additional linear regression models were constructed separately for each group. To further interrogate any FAT effects, tests were repeated for the ADT and RDT values.

Bonferroni corrected Pearson product moment (when normally distributed) or Spearman correlation analyses tested for associations between diffusivity measures (FAT and FW) and clinical characteristics (duration of symptoms, functional decline, and four SOPS scores). In the results section below, p-values are reported as significant if they were lower than the Bonferroni corrected threshold equivalent to p=0.05. For comparison with previous DTI studies, selected analyses were also performed for the conventional FA measure.

To identify the spatial extent of group differences, in a second level of analysis permutation tests were used for group comparisons for each voxel on the white matter skeleton, using the randomize tool in FSL (48). Threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) (49) was applied to control for family wise errors, with a significance threshold (that is TFCE modified) of p<0.05. Age, gender, and motion were included as covariates. Anatomical locations were identified using the ICBM-DTI-81 atlas (50).

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

There were no significant differences between CHR subjects and HCs in age, gender, education, motion, or handedness (see Table 2). CHR subjects experienced attenuated positive symptoms (see Table 1), manifested primarily as elevated symptoms on P1 (unusual thought content/delusional ideas) and P2 (suspiciousness/persecutory ideas) of the SOPS. Mean duration of prodromal symptoms at assessment was 6.5 (SD=6.2) months. Forty of the 50 CHR subjects were never medicated with antipsychotics. Ten subjects had received antipsychotic or antidepressant medications: nine subjects for less than 3 weeks (aripiprazole-3, risperidone-2, quetiapine-1, sulpiride-1, citaplopram-1, and olanzapine, paroxetine and lamotrigine-1), and one subject had received one antipsychotic medication for three months (risperidone-1). The ten medicated subjects (8 males, 2 females, mean age 19.3 ± 3.7 years) had significantly more functional decline than non-medicated subjects (t(48)=2.115, p=0.040), and more negative symptoms at the trend level (t(48)=1.775, p=0.082). There were no other significant differences in demographics or clinical variables between the medicated and non-medicated CHR (Supplementary Table S1).

Within the one year follow up evaluation, 11 CHR subjects (7 males, 4 females, mean age 18.4 ± 2.2 years) converted to psychosis, and were diagnosed with schizophrenia. The average time between initial assessment and conversion was 6.27 months (S.D.=5.96; range 1 to 17 months). Nine converted CHRs were never medicated at the baseline. There were no significant differences in age, gender or clinical scores between subjects who converted to psychosis and subjects who did not convert.

Whole Brain Average Diffusivity Comparison of CHR and HC

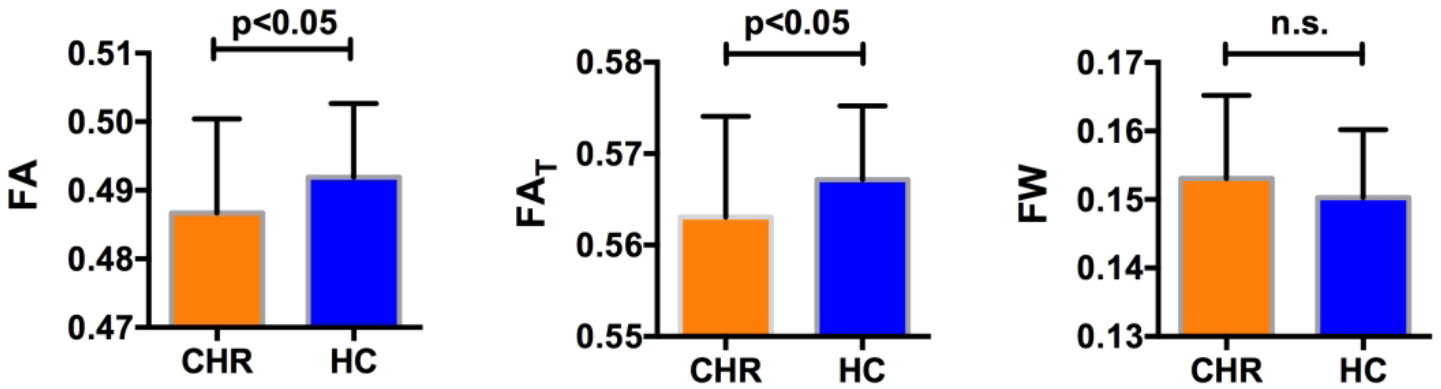

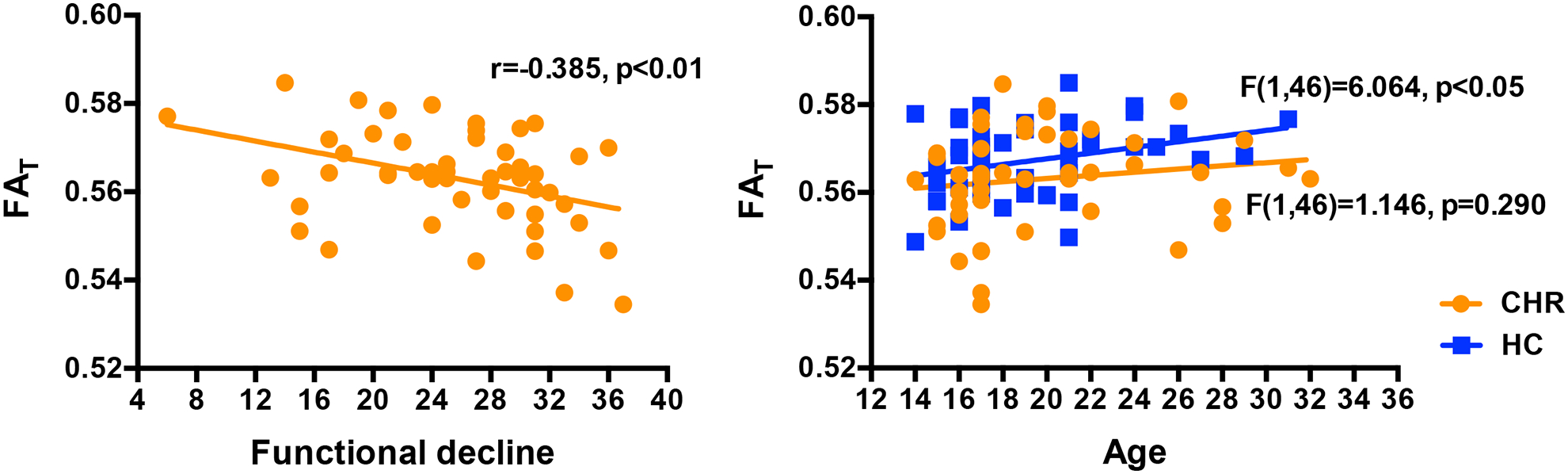

In comparing average diffusivities across the entire white matter skeleton we found that CHR had significantly lower FA (F(1,95)=5.672, p=0.019, Cohen’s d=−0.422; 0.487±0.002 for CHR and 0.492 ± 0.002 for HC) compared with HC (Figure 1). When applying the free-water model, we found that CHR had significantly lower FAT (F(1,95)=5.556, p=0.020, Cohen’s d=−0.424; 0.563±0.002 for CHR and 0.567±0.001 for HC) but not significantly higher FW (F(1,95)=2.243, p=0.137, Cohen’s d=0.034; 0.153±0.002 for CHR and 0.150±0.001 for HC) compared with HC (Figure 1). The lower FAT coincided with lower ADT (F(1,95)=6.348, p=0.013, Cohen’s d= −0.499) but not with higher RDT (F(1,95)=1.295, p=0.258, Cohen’s d= 0.164). Additionally, FAT (r(48)=−0.385, p=0.006; Figure 2) was negatively correlated with functional decline among CHRs, i.e., subjects with lower FAT tended to have more functional decline. A significant correlation with functional decline was also found for the ADT measure (r(48)=−0.299, p=0.035) and for the RDT measure (r(48)=0.300, p=0.034). The uncorrected FA measure also correlated with functional decline, although to a lesser degree than FAT (r(48)=−0.357, p=0.011). There was no significant correlation between FW and functional decline (r(48)=0.161, p=0.265). There were also no significant correlations between the diffusion measures (FA, FAT, ADT, RDT, and FW) and any additional clinical score.

Figure 1:

Subjects with clinical high risk for psychosis (CHR) had statistically significantly lower average FA (left) over the whole white matter skeleton compared with healthy controls (HC). Free-water imaging measures showed that the CHR group had significant lower FAT (center) but no group difference in FW (right), suggesting that the lower FA may be explained by cellular changes rather than by extracellular changes.

Figure 2:

FAT was statistically significantly negatively correlated with functional decline over a period of 12 months in patients (left). FAT was also statistically significantly positively correlated with age (right) in HC but not in CHR.

Gender (F(1,95)=4.337, p=0.040) and age (F(1,95)=5.951, p=0.017) were significant predictors of FAT across the entire sample. There was no significant interaction of group and gender (F(2,97)=1.706, p=0.187). However, for FAT there was a significant interaction of group and age (F(2,97)=4.789, p=0.010), suggesting age related differences between groups. Follow-up linear models within HC showed that FAT was positively correlated with age (F(1,46)=6.064, p=0.018). However, within CHR, FAT was not correlated with age (F(1,46)=1.146, p=0.290).

There were no significant differences between non-medicated CHR subjects and CHR subjects who received antipsychotics on either of the free-water measures (F(1,45)=2.003, p=0.164, Cohen’s d=0.425 for FAT and F(1,45)=0.051, p=0.822, Cohen’s d=0.018 for FW). For the non-medicated CHR subjects, correlation with functional decline remained significant (r(38)=−0.397, p=0.011), and there was a trend level decrease in FAT compared with HC (F(1,85)=2.931, p=0.091, Cohen’s d=−0.278). There were no significant group differences in FAT (F(1,45)=2.078, p=0.156, Cohen’s d=0.423) or FW (F(1,45)=0.006, p=0.939, Cohen’s d=0.128) between subjects who converted to psychosis and subjects who did not convert.

Voxel-wise Analyses

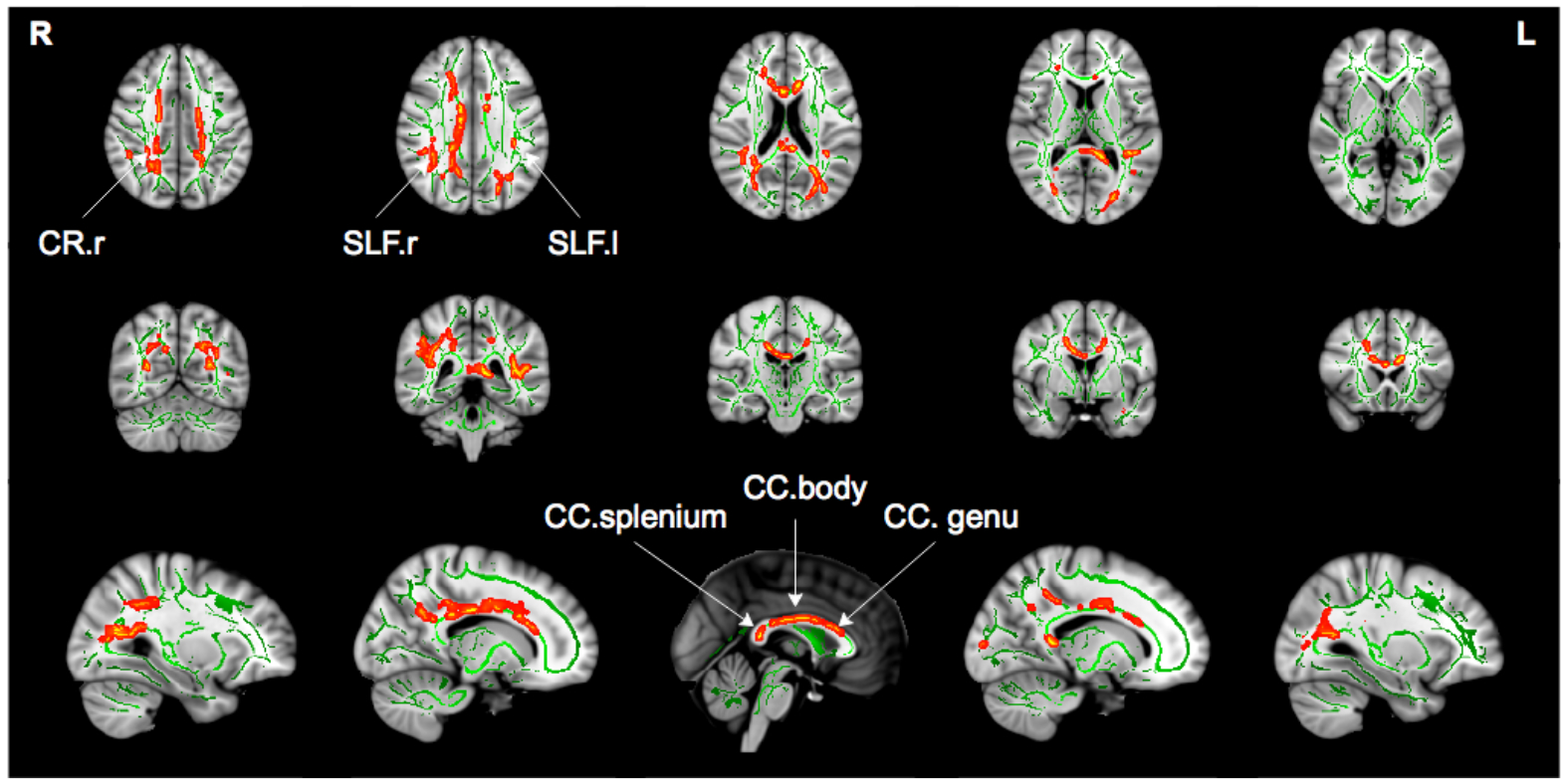

To understand better the extent of microstructural alterations, FAT and FW were compared between the CHR and HC groups using a voxel wise TBSS analysis. Similar to the whole brain analysis above, there were no group differences in FW. The statistical analysis identified lower FAT in the CHR group in 4% of the skeleton (5363 voxels), and in the following locations: the genu, body and splenium of corpus callosum, right anterior, superior and posterior corona radiata (CR), and bilateral superior longitudinal fasciculus (Figure 3). These locations largely overlapped with the group differences in FA (Supplementary Figure S1), which covered 10.6% of the skeleton (14267 voxels). There were no voxel-wise correlations between FAT and clinical parameters. However, there was a significant correlation (r(48)=−0.405, p=0.004) between functional decline and FAT averaged across all voxels that showed significant FAT group differences. There were no significant voxel-wise group differences in ADT or RDT. Also, we did not identify any significant group differences between subjects who converted to psychosis and subjects who did not convert.

Figure 3:

Tract based spatial statistics analysis showed significantly lower FAT values (p<0.05, corrected for family wise error) in CHR subjects compared with healthy controls. Significant lower FAT values (red to yellow) are drawn on top of the white matter skeleton (green) within the clusters including the genu, body and splenium of the corpus callosum (CC), right anterior, superior and posterior corona radiata (CR), and bilateral superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF).

DISCUSSION

We report differences in the white matter of a large and predominantly medication-naïve cohort of CHR subjects compared with HC. We demonstrate that the abnormalities observed in CHR originate from cellular (FAT) rather than from extracellular differences (FW) in the brain. This is in contrast to previous findings in first psychotic episode patients who presented with a large extent of extracellular differences in addition to cellular differences (18, 30). We further note that the cellular differences are manifested as an abnormal age related effects, and are associated with functional decline. We note, however, that our analyses assumed a linear relationship of the diffusion parameters with age, and were based on cross-sectional data. More accurate longitudinal models that are based on larger sample sizes are needed to better characterize the relationship with age, as well as group differences in age related effects. Our findings thus suggest that early cellular alterations appear prior to psychosis onset in subjects experiencing attenuated psychotic symptoms.

The finding of lower FAT is in agreement with previous studies that have observed lower FA and FAT in CHR subjects (36–38). FAT is meant to improve the specificity of the measurement to processes that occur within or around neuronal tissue. FAT is expected to show less group differences than FA when much of the group differences originate from extracellular processes (e.g., (18, 30, 51)). On the other hand, in some instances extracellular processes may dominate the signal, but may not show differences between the groups, in which case FAT would show more findings than FA (e.g., (52)). Finally, if there is not a big contribution to the signal from extracellular processes, FAT is expected to be similar to FA (19). Our study goes further, therefore, in that it helps to establish that microstructural abnormalities, which are apparent already in the CHR phase, likely originate from the tissue itself and not from extracellular free-water. Of further note, in the current study, the exact underlying pathology related with cellular alterations is difficult to determine. Nevertheless, the cellular alterations were correlated with more functional decline over time, rather than with the current symptom levels, which may suggest an ongoing deterioration. This correlation remained significant when excluding medicated subjects, providing reassurance that this is not a medication effect. In addition, the positive correlation between FAT and age in HC, which was not observed in CHR, suggests an abnormal age related effect in CHR.

Within the age range observed here, many of the white matter bundles are still at a stage of development before reaching a peak in anisotropy (53). The lack of a positive correlation between FAT and age in CHR may therefore suggest that white matter fiber development in CHR was prematurely disrupted, which possibly points to a neurodevelopmental anomaly. Also supporting this hypothesis is that FAT changes were associated with ADT changes that are thought to be more related to axonal organization, and not with RDT changes that are thought to be more related to neurodegeneration or demyelination (54). Taken together, the FAT group differences raise the possibility that initial pre-existing cellular anomalies pose a predisposition for the development of symptoms, and that any subsequent cellular deterioration determines the severity of the functional decline experienced by the subjects. This possibility could be tested by obtaining longitudinal imaging in CHR subjects prior to onset of psychosis.

The location of FAT group differences included the genu, body and splenium of the corpus callosum, right anterior, superior and posterior CR, and bilateral SLF. These differences found in a Chinese population are in line with previous whole-brain studies of CHR cohorts (33, 34, 36, 37). In particular, white matter abnormalities within SLF, which connects the fronto-parieto-temporal regions, are the most frequent abnormalities reported in CHR subjects (33, 34, 36). Interestingly, we report more locations with FAT group differences than in our previous studies of first-episode patients with psychosis (18, 30). Since it is not likely that cellular changes diminish with the progression of the disorder, we believe that several differences in the design of the current study likely lead to higher sensitivity for identifying FAT group differences. These design differences include a larger sample size that is better powered to identify group differences, and an improved multi-shell acquisition method, which provides better signal to noise ratio and a more robust model fit. The higher sensitivity of the multi-shell sequence can also be appreciated by noting the higher spatial extent of FAT group differences in the current study compared with a previous single shell study with a similar population (38).

Of particular note, based on our previous studies of subjects following their first psychotic episode (18, 30) we predicted that FW would be higher in CHR subjects. However, we did not find extracellular FW group differences in the current CHR population. Since the current study is better powered and uses a more sophisticated diffusion MRI sequence than previous studies, the lack of FW finding suggests that FW changes are either absent or much more subtle than those observed in first episode subjects. Thus, the current study suggests that substantial FW alterations may appear closer to psychosis onset as opposed to the current CHR population, where psychosis was not present. The absence of higher FW in CHR substantiates a hypothesis that an increase in FW likely represents an acute response of the brain to psychosis, and that the increase arrives to a peak following the first psychotic episode, and then declines in the chronic phases (27). Such a hypothesis could be tested in future studies, especially by following CHR subjects longitudinally, where an increase in FW is predicted in those subjects who convert to psychosis, compared with those who do not. Relating increased FW with acute response to psychosis may lead to treatment approaches that may prevent such an increase at the CHR stage (e.g., anti-inflammatory treatments), which may also prevent the outbreak of psychosis.

Limitations of the current study include the cross-sectional nature of this analysis and the fact that the sample was not powered to identify differences between subjects who developed psychosis compared with those who did not. CHR is an early, potentially recoverable stage of psychotic disorder (55) and thus it could be argued that CHR may not be representative of psychosis. However, all CHR subjects experienced attenuated psychotic symptoms, and it may be that conversion to psychosis is determined by the interaction of neuropathology with external factors and life events, quality of the support system, environmental factors, treatment strategies and response to treatment, or with supervening pathophysiological processes, such as neuroinflammation, that add to an already existing biological vulnerability (56). Future assessments in a large, longitudinal sample of subjects who converted to psychosis in order to validate our current findings will be important. While the current cohort was largely drug naïve, our results suggest that group differences, in part, may be contributed to medication status, and/or proxy of greater symptom severity. Future studies with a sufficient number of medicated and non-medicated subjects are needed to establish whether or not medication has an effect on the diffusion MRI measures. We note that while this cohort was acquired in China, it followed the same procedures and protocols as our other studies that were collected in the USA. Therefore, we do not expect technical differences to affect our results, although genetic differences between Chinese cohorts and Western cohorts may contribute to some of the differences between the current and previous studies. The specific multi-shell sequence that we used here was designed to support the model based quantitative analysis in addition to tractography studies. Free-water is visible in the low b-value range, and here we added two lower shells. In low b-values the signal profile is isotropic, and therefore requires fewer gradient orientations, however the acquisition could be further optimized in future work. We note that the high b-value shell was not used in the current study since it is not appropriate to include in a Gaussian diffusion model such as the free-water imaging. The information in the high b-value shell awaits future work with non-Gaussian models or tractography studies.

In conclusion, our data indicate microstructural white matter alterations are present in CHR subjects who are experiencing attenuated psychotic symptoms, prior to the onset of psychosis, and which are associated with functional decline, as well as possibly reflecting a predisposition to develop attenuated psychotic symptoms. In contrast, higher extracellular FW was not observed in this CHR population, suggesting that previously reported extracellular processes, such as neuroinflammation, may play a more prominent role closer to or at onset of psychosis. As we follow up this sample longitudinally, we will be able to provide important new information bearing on the relationship between white matter changes and the emergence of psychosis.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures and acknowledgments

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of China, National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC1306800), National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH101052, R01MH111448, R01MH074794, R01MH102377, R01MH108574, K23MH102358), National Nature Science Foundation of China (81361120403, 81671332, 81671329, 81871050), VA grant (2I01 CX000176, CX000157), Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (16JC1420200, 17411953100) and the Clinical Research Center at Shanghai Mental Health Center (CRC2018ZD01, CRC2018ZD04 and CRC2018YB01). YT was funded by a Municipal Human Resources Development Program for Outstanding Young Talents in Medical and Health Sciences in Shanghai (2017YQ069).

REFERENCE

- 1.Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA: Schizophrenia,“just the facts” what we know in 2008. 2. Epidemiology and etiology. Schizophr Res 2008;102:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yung AR, Yung AR, Pan Yuen H, et al. : Mapping the onset of psychosis: The comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2005;39:964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpenter WT, Schiffman J: Diagnostic concepts in the context of clinical high risk/attenuated psychosis syndrome. Schizophr Bull 2015;41(5):1001–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, et al. : The psychosis high-risk state: A comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. : Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: A multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008;65:28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon TD, Chung Y, He G, et al. : Progressive reduction in cortical thickness as psychosis develops: A multisite longitudinal neuroimaging study of youth at elevated clinical risk. Biol Psychiatry 2015;77:147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, et al. : Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:220–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mechelli A, Riecher-Rössler A, Meisenzahl EM, et al. : Neuroanatomical abnormalities that predate the onset of psychosis: A multicenter study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzsimmons J, Kubicki M, Shenton ME: Review of functional and anatomical brain connectivity findings in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2013;26:172–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friston KJ, Frith CD: Schizophrenia: A disconnection syndrome. Clin Neurosci 1995;3:89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinze K, Reniers RLEP, Nelson B, et al. : Discrete alterations of brain network structural covariance in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 2015;77:989–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samartzis L, Dima D, Fusar ‐Poli P, et al. : White matter alterations in early stages of schizophrenia: A systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies. J Neuroimaging 2014;24:101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wheeler AL, Voineskos AN: A review of structural neuroimaging in schizophrenia: From connectivity to connectomics. Front Hum Neurosci 2014;8:653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basser PJ, Mattiello J, LeBihan D: MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys J 1994;66:259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assaf Y, Pasternak O: Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)-based white matter mapping in brain research: A review. J Mol Neurosci 2008;34:51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubicki M, McCarley R, Westin C-F, et al. : A review of diffusion tensor imaging studies in schizophrenia. J Psychiatric Res 2007;41:15–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Schneider T, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, et al. : NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage. 2012;61:1000–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasternak O, Westin C-F, Bouix S, et al. : Excessive extracellular volume reveals a neurodegenerative pattern in schizophrenia onset. J Neurosci 2012;32:17365–17372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasternak O, Sochen N, Gur Y, et al. : Free water elimination and mapping from diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med 2009;62:717–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Donnell LJ, Pasternak O: Does diffusion MRI tell us anything about the white matter? An overview of methods and pitfalls. Schizophr Res 2015;161:133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kochunov P, Chiappelli J, Wright SN, et al. : Multimodal white matter imaging to investigate reduced fractional anisotropy and its age-related decline in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2014;223:148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kochunov P, Chiappelli J, Hong LE: Permeability-diffusivity modeling vs. fractional anisotropy on white matter integrity assessment and application in schizophrenia. NeuroImage Clin 2013;3:18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasternak O, Shenton ME, Westin C-F: Estimation of extracellular volume from regularized multi-shell diffusion MRI. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv 2012. pp. 305–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones DK, Knösche TR, Turner R: White matter integrity, fiber count, and other fallacies: The do’s and don’ts of diffusion MRI. Neuroimage. 2013;73:239–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melonakos ED, Shenton ME, Rathi Y, et al. : Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) studies in schizophrenia - can white matter changes be reliably detected with VBM? Psychiatry Res 2011;193:65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasternak O, Kubicki M, Shenton ME: In vivo imaging of neuroinflammation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasternak O, Westin C-F, Dahlben B, et al. : The extent of diffusion MRI markers of neuroinflammation and white matter deterioration in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2015;161:113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Cusick MF, Wang Y, et al. : Diffusion basis spectrum imaging detects and distinguishes coexisting subclinical inflammation, demyelination and axonal injury in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. NMR Biomed 2014;27:843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scherrer B, Warfield SK: Parametric representation of multiple white matter fascicles from cube and sphere diffusion MRI. PLoS One 2012;7:e48232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyall AE, Pasternak O, Robinson DG, et al. : Greater extracellular free-water in first-episode psychosis predicts better neurocognitive functioning. Mol Psychiatry 2018;23(3):701–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters BD, De Haan L, Dekker N, et al. : White matter fibertracking in first-episode schizophrenia, schizoaffective patients and subjects at ultra-high risk of psychosis. Neuropsychobiology 2008;58:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters BD, Dingemans PM, Dekker N, et al. : White matter connectivity and psychosis in ultrahigh-risk subjects: A diffusion tensor fiber tracking study. Psychiatry Res 2010;181:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bloemen OJN, De Koning MB, Schmitz N, et al. : White-matter markers for psychosis in a prospective ultra-high-risk cohort. Psychol Med 2010;40:1297–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlsgodt KH, Niendam TA, Bearden CE, et al. : White matter integrity and prediction of social and role functioning in subjects at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:562–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters BD, Schmitz N, Dingemans PM, et al. : Preliminary evidence for reduced frontal white matter integrity in subjects at ultra-high-risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res 2009;111:192–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carletti F, Woolley JB, Bhattacharyya S, et al. : Alterations in white matter evident before the onset of psychosis. Schizophr Bull 2012;38:1170–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Hohenberg CC, Pasternak O, Kubicki M, et al. : White matter microstructure in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis: A whole-brain diffusion tensor imaging study. Schizophr Bull 2014; 40(4):895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang C, Ji F, Hong Z, et al. : Disrupted salience network functional connectivity and white-matter microstructure in persons at risk for psychosis: findings from the LYRIKS study. Psychol Med 2016;46:2771–2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang T, Li H, Woodberry KA, et al. : Prodromal psychosis detection in a counseling center population in China: An epidemiological and clinical study. Schizophr Res 2014;152:391–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng L, Wang J, Zhang T, et al. : The Chinese version of the SIPS/SOPS: A pilot study of reliability and validity. Chinese Mental Health Journal 2012;26:571–576. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang T, Li H, Tang Y, et al. : Screening schizotypal personality disorder for detection of clinical high risk of psychosis in Chinese mental health services. Psychiatry Res 2015;228:664–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chon MW, Lee TY, Kim SN, et al. : Factors contributing to the duration of untreated prodromal positive symptoms in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res 2015;162:64–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGlashan T, Walsh B, Woods S: The psychosis-risk syndrome: Handbook for diagnosis and follow-up, Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang TH, Li HJ, Woodberry KA, et al. : Two-year follow-up of a Chinese sample at clinical high risk for psychosis: Timeline of symptoms, help-seeking and conversion. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2017;26(3):287–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, et al. : Tract-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage 2006;31:1487–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, et al. : Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 2004;23:S208–S219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taquet M, Scherrer B, Boumal N, et al. : Improved fidelity of brain microstructure mapping from single-shell diffusion MRI. Med Image Anal 2015;26:268–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winkler AM, Ridgway GR, Webster MA, et al. : Permutation inference for the general linear model. Neuroimage 2014;92:381–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith SM, Nichols TE: Threshold-free cluster enhancement: Addressing problems of smoothing threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 2009;44:83–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mori S, Wakana S, Van Zijl PCM, et al. : MRI atlas of human white matter, Am Soc Neuroradiology; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tuozzo C, Lyall AE, Pasternak O, et al. : Patients with chronic bipolar disorder exhibit widespread increases in extracellular free water, Bipolar Disord 2018;20:523–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maier-Hein KH, Westin CF, Shenton ME, et al. : Widespread white matter degeneration preceding the onset of dementia. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:485–493.e482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kochunov P, Hong LE: Neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative models of schizophrenia: White matter at the center stage. Schizophr Bull 2014;40(4):721–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Song SK, Sun SW, Ramsbottom MJ, et al. : Dysmyelination revealed through MRI as increased radial (but unchanged axial) diffusion of water. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1429–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McGorry PD: Issues for DSM-V: clinical staging: A heuristic pathway to valid nosology and safer, more effective treatment in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:859–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McGorry P, Keshavan M, Goldstone S, et al. : Biomarkers and clinical staging in psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2014;13:211–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.