This phase 2b, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial evaluates the efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, a novel, high-affinity, monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin (IL)–13 that selectively prevents formation of the IL-13Rα1/IL-4Rα heterodimer receptor signaling complex, in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

Key Points

Question

Is lebrikizumab, a novel, high-affinity, monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin 13 that selectively inhibits interleukin 13 signaling, efficacious and safe in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis?

Findings

Among 280 patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in this phase 2b, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial, lebrikizumab statistically significantly improved measures of clinical manifestations of atopic dermatitis, pruritus, and quality of life in a dose-dependent manner vs placebo during 16 weeks of treatment.

Meaning

Lebrikizumab was efficacious for adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, was generally well tolerated, and had a favorable safety profile consistent with previous lebrikizumab studies; these data support the central role of interleukin 13 in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis.

Abstract

Importance

Interleukin 13 (IL-13) is a central pathogenic mediator driving multiple features of atopic dermatitis (AD) pathophysiology.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, a novel, high-affinity, monoclonal antibody targeting IL-13 that selectively prevents formation of the IL-13Rα1/IL-4Rα heterodimer receptor signaling complex, in adults with moderate to severe AD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A phase 2b, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging randomized clinical trial of lebrikizumab injections every 4 weeks or every 2 weeks was conducted from January 23, 2018, to May 23, 2019, at 57 US centers. Participants were adults 18 years or older with moderate to severe AD.

Interventions

Patients were randomized 2:3:3:3 to placebo every 2 weeks or to subcutaneous injections of lebrikizumab at the following doses: 125 mg every 4 weeks (250-mg loading dose [LD]), 250 mg every 4 weeks (500-mg LD), or 250 mg every 2 weeks (500-mg LD at baseline and week 2).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was percentage change in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) (baseline to week 16). Secondary end points for week 16 included proportion of patients achieving Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (IGA 0/1); EASI improvement of at least 50%, 75%, or 90% from baseline; percentage change in the pruritus numeric rating scale (NRS) score; and pruritus NRS score improvement of at least 4 points. Safety assessments included treatment-emergent adverse events.

Results

A total of 280 patients (mean [SD] age, 39.3 [17.5] years; 166 [59.3%] female) were randomized to placebo (n = 52) or to lebrikizumab at doses of 125 mg every 4 weeks (n = 73), 250 mg every 4 weeks (n = 80), or 250 mg every 2 weeks (n = 75). Compared with placebo (EASI least squares mean [SD] percentage change, −41.1% [56.5%]), lebrikizumab groups showed dose-dependent, statistically significant improvement in the primary end point vs placebo at week 16: 125 mg every 4 weeks (−62.3% [37.3%], P = .02), 250 mg every 4 weeks (−69.2% [38.3%], P = .002), and 250 mg every 2 weeks (−72.1% [37.2%], P < .001). Differences vs placebo-treated patients (2 of 44 [4.5%]) in pruritus NRS improvement of at least 4 points were seen as early as day 2 in the high-dose lebrikizumab group (9 of 59 [15.3%]). Treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 24 of 52 placebo patients (46.2%) and in lebrikizumab patients as follows: 42 of 73 (57.5%) for 125 mg every 4 weeks, 39 of 80 (48.8%) for 250 mg every 4 weeks, and 46 of 75 (61.3%) for 250 mg every 2 weeks; most were mild to moderate and did not lead to discontinuation. Low rates of injection-site reactions (1 of 52 [1.9%] in the placebo group vs 13 of 228 [5.7%] in all lebrikizumab groups), herpesvirus infections (2 [3.8%] vs 8 [3.5%]), and conjunctivitis (0% vs 6 [2.6%]) were reported.

Conclusions and Relevance

During 16 weeks of treatment, lebrikizumab provided rapid, dose-dependent efficacy across a broad range of clinical manifestations in adult patients with moderate to severe AD and demonstrated a favorable safety profile. These data support the central role of IL-13 in AD pathophysiology. If these findings replicate in phase 3 studies, lebrikizumab may meaningfully advance the standard of care for moderate to severe AD.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03443024

Introduction

The pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis (AD) is multifaceted, involving a complex interplay of several factors, including genetics, environment, and dysregulated immune pathways.1,2,3,4 A central feature in AD immunopathogenesis is dysregulation of helper T-cell type 2 (TH2) cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells, which leads to a robust increase in type 2 immune cytokines,5 including interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-13, and IL-31. Previous studies3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 have shown that IL-13 has important roles in inflammation, skin barrier dysfunction, skin thickening, infections, pruritus, and allergic responses that characterize AD. Interleukin 13 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression is elevated in both lesional and nonlesional skin vs healthy control tissues, with IL-13 mRNA levels correlating with disease severity.14 In circulation, T cells producing IL-13 are also increased in patients with AD and correlate with disease activity.12,15,16,17,18,19,20

Lebrikizumab is a novel, high-affinity, monoclonal antibody that selectively targets IL-13 and prevents formation of the IL-13Rα1/IL-4Rα heterodimer receptor signaling complex. Lebrikizumab does not prevent IL-13 binding to the IL-13Rα2 decoy receptor,6 which is thought to be involved in endogenous regulation of IL-13. In a phase 2a proof-of-concept trial in adults with moderate to severe AD, overall results with lebrikizumab in single doses or once monthly in combination with a topical corticosteroid (TCS) showed a dose-dependent response and generally positive findings on key outcomes.21 Findings of the phase 2a proof-of-concept study21 informed the design of our phase 2b dose-ranging trial. This article reports results of the phase 2b randomized clinical trial assessing the efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab monotherapy every 4 weeks or every 2 weeks in adults with moderate to severe AD.

Methods

This randomized clinical trial was conducted at 57 US centers. The trial protocol (Supplement 1) and the written informed consent form were approved by local institutional review boards or independent ethics committees. The trial was conducted from January 23, 2018, to May 23, 2019, and the study was undertaken in accord with current US federal regulations, US Food and Drug Administration guidelines,22 the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice,23 and the Declaration of Helsinki.24 This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines.

Study Design

This phase 2b, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-ranging randomized clinical trial of lebrikizumab injections every 4 weeks or every 2 weeks consisted of a 16-week treatment period with a 16-week safety follow-up (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Patients sequentially received a screening number assigned via iMedidata Rave (Medidata Solutions Worldwide, Inc). After a screening period not exceeding 30 days and after eligibility requirements were confirmed on day 1 (baseline), screening numbers were entered into an interactive web response system, and patients were randomized 2:3:3:3 to matching placebo every 2 weeks or to subcutaneous injections of lebrikizumab at the following doses: 125 mg every 4 weeks (250-mg loading dose [LD]), 250 mg every 4 weeks (500-mg LD), or 250 mg every 2 weeks (500-mg LD at baseline and week 2). Additional study design details are available in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

The sponsor (Dermira, Inc), investigators, study site personnel, and patients were blinded to treatment assignments, and blind integrity was maintained throughout the study. Blinded, coded kits with study drug in prefilled syringes and boxes masked the treatment assignments.

Rescue therapy was allowed to manage patient symptoms and to inform the phase 3 program.25,26 Topical corticosteroid rescue was considered preferable before systemic rescue treatment. Patients requiring a TCS could remain in the study and were to continue TCS use as briefly as possible; those requiring systemic rescue therapy were discontinued from the study.

Study Patients

Eligible patients were adults 18 years or older with moderate to severe AD (Eczema Area and Severity Index [EASI]27 of at least 16), Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of at least 3, at least 10% of the total body surface area (BSA) affected, and chronic AD28 for at least 1 year and for whom topical treatment was inadequate or inadvisable. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are available in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Efficacy and Safety Assessments

The prespecified primary end point was percentage change from baseline in the EASI to week 16. Secondary end points reported herein for week 16 included the following: proportion of patients achieving an IGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) (IGA 0/1) on a 5-point scale (score range, 0-4) (eTable 1 in Supplement 2); proportion of patients with at least 50%, at least 75%, and at least 90% improvement from baseline on the EASI (EASI50, EASI75, and EASI90, respectively); percentage change from baseline on the pruritus numeric rating scale (NRS) score (11-point scale assessing “worst” itch in the prior 24 hours); proportion of patients with at least a 4-point improvement in pruritus NRS score from baseline; percentage change from baseline in total BSA involvement; change from baseline in Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) total score (range, 0 [clear] to 28 [very severe]); and change from baseline in the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (range, 0 [no effect of skin disease on quality of life] to 30 [maximum effect on quality of life]). Visits occurred every 2 weeks through week 16 and at weeks 20 and 24, with a safety telephone follow-up at week 32 (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Safety assessments included treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs).

Statistical Analysis

The sample size (target number, approximately 275 patients) was based mainly on prior study results, including TCS use,21 which defined an estimated sample size of approximately 75 patients for active groups and 50 for the placebo group to adequately power the study. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc). No interim analyses were planned or performed. All statistical tests were 2-sided and performed at the .05 level of significance. Statistical comparisons were performed at week 16 only and between lebrikizumab groups and placebo only. Efficacy analyses used the modified intent-to-treat population (all patients who were randomized and received study drug regardless of rescue medication use). Safety analyses used the safety population (those randomized who received ≥1 dose of study drug).

The primary end point was evaluated using an analysis of covariance with a factor of treatment group and corresponding baseline EASI as the covariate. Missing efficacy data were imputed using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, which do not rely on the assumption of data missing at random. The binary secondary end points of the proportion of patients with IGA 0/1, EASI50, EASI75, and EASI90 and the proportion of patients with at least a 4-point improvement in pruritus NRS score were evaluated with pairwise Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests. Missing values were imputed with MCMC for IGA 0/1 response and EASI; no imputations were made for the proportion of patients with at least a 4-point improvement in pruritus NRS score. The continuous secondary end points of percentage change in pruritus NRS score and change in total BSA involvement were evaluated with an analysis of covariance; no imputations were made for missing pruritus NRS score from baseline or missing total BSA involvement. Change from baseline in POEM total score and DLQI were analyzed descriptively, with no data imputation.

The following 3 sensitivity analyses were prespecified to evaluate the robustness of response for IGA 0/1 and EASI75: (1) nonresponder imputation for all missing values, (2) repeated-measures analyses on observed data (also performed for the primary end point), and (3) nonresponder imputation for rescue medication use and last observation carried forward for other missing values (additional details are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 2). A post hoc analysis was performed for pruritus NRS score (MCMC imputation).

Results

Patient Disposition, Baseline Demographics, and Disease Characteristics

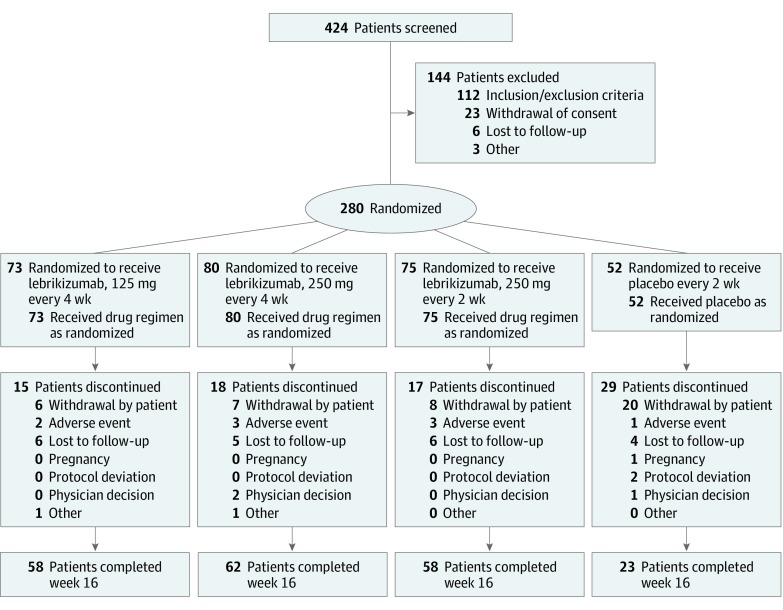

A total of 280 patients (mean [SD] age, 39.3 [17.5] years; 166 [59.3%] female) were randomized to placebo (n = 52) or to lebrikizumab at the following doses: 125 mg every 4 weeks (n = 73), 250 mg every 4 weeks (n = 80), or 250 mg every 2 weeks (n = 75) (Figure 1). Week 16 completion rates were greater for lebrikizumab-treated patients vs placebo-treated patients (44.2% [23 of 52] for placebo and 79.5% [58 of 73], 77.5% [62 of 80], and 77.3% [58 of 75] for 125 mg of lebrikizumab every 4 weeks, 250 mg every 4 weeks, and 250 mg every 2 weeks [hereinafter, the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively]). The most common reasons for discontinuation were withdrawal by patient (41 of 280 [14.6%]), lost to follow-up (21 of 280 [7.5%]), and adverse event (9 of 280 [3.2%]).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram Showing Patient Disposition.

CONSORT indicates Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics were well matched across groups (Table 1). Consistent with inclusion criteria, the patient population exhibited symptoms of moderate to severe AD based on IGA score, EASI, pruritus NRS score, percentage BSA involvement, and DLQI. A total of 16 patients (4 placebo and 12 lebrikizumab) self-reported prior dupilumab use.

Table 1. Baseline Demographics and Disease Characteristics in the Modified Intent-to-Treat Populationa.

| Variable | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo Every 2 wk (n = 52) | Lebrikizumab | |||

| 125 mg Every 4 wk (n = 73) | 250 mg Every 4 wk (n = 80) | 250 mg Every 2 wk (n = 75) | ||

| Baseline Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 42.2 (18.2) | 36.7 (16.5) | 40.2 (17.9) | 38.9 (17.4) |

| Female | 24 (46.2) | 46 (63.0) | 47 (58.8) | 49 (65.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 26 (50.0) | 37 (50.7) | 42 (52.5) | 40 (53.3) |

| Black or African American | 16 (30.8) | 26 (35.6) | 28 (35.0) | 23 (30.7) |

| American Indian or Alaskan native | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) |

| Asian | 6 (11.5) | 8 (11.0) | 7 (8.8) | 6 (8.0) |

| Multiple or other | 4 (7.7) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.5) | 5 (6.7) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 5 (9.6) | 14 (19.2) | 11 (13.8) | 12 (16.0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 47 (90.4) | 59 (80.8) | 69 (86.3) | 63 (84.0) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29.7 (8.0) | 30.1 (7.7) | 29.2 (6.9) | 28.1 (6.4) |

| Baseline Disease Characteristics | ||||

| Disease duration, mean (SD), y | 24.4 (17.4) | 22.8 (15.4) | 23.3 (16.7)b | 22.1 (17.2) |

| Prior dupilumab use | 4 (7.7) | 4 (5.5) | 3 (3.8) | 5 (6.7) |

| IGA | ||||

| 3, Moderate | 32 (61.5) | 43 (58.9) | 54 (67.5) | 53 (70.7) |

| 4, Severe | 20 (38.5) | 30 (41.1) | 26 (32.5) | 22 (29.3) |

| EASI, mean (SD) | 28.9 (11.8) | 29.9 (13.5) | 26.2 (10.1) | 25.5 (11.2) |

| Pruritus NRS score, mean (SD)c | 7.4 (2.4) | 7.6 (2.0) | 7.1 (2.4) | 7.6 (1.9) |

| Sleep loss NRS score, mean (SD)d | 1.8 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.0 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.2) |

| BSA involvement, mean (SD), % | 46.5 (22.7) | 45.5 (24.5) | 41.1 (20.9) | 39.4 (21.5) |

| POEM total score, mean (SD) | 19.4 (6.8) | 21.5 (5.7)e | 19.9 (6.7) | 20.4 (5.7) |

| DLQI, mean (SD) | 14.1 (7.1) | 14.5 (7.1)e | 14.2 (7.7) | 14.1 (6.9) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index (range, 0 [no effect of skin disease on quality of life] to 30 [maximum effect on quality of life]); EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment (5-point scale); NRS, numeric rating scale; POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (range, 0 [clear] to 28 [very severe]).

Percentages are based on the number of patients in the modified intent-to-treat population with a nonmissing response.

Sample size is n = 79.

Sample sizes are as follows: n = 49 for placebo and n = 68, n = 77, and n = 69 for the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively.

Sample sizes are as follows: n = 49 for placebo and n = 68, n = 77, and n = 70 for the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively. Sleep loss NRS scores reflect interference of itch on sleep over the past 24 hours on a 5-point scale (0 indicates not at all, and 4 indicates unable to sleep at all).

Sample size is n = 72.

Primary End Point

Compared with placebo (EASI least squares mean [SD] percentage change, −41.1% [56.5%]), lebrikizumab groups showed dose-dependent, statistically significant improvement in the primary end point vs placebo at week 16: 125 mg every 4 weeks (−62.3% [37.3%], P = .02), 250 mg every 4 weeks (−69.2% [38.3%], P = .002), and 250 mg every 2 weeks (−72.1% [37.2%], P < .001) (Table 2). Dose-dependent differences in mean percentage change in the EASI between placebo-treated patients and lebrikizumab-treated patients were observed as early as the first visit (week 4), with further improvements to week 16 (statistical comparison at week 16 only) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2).

Table 2. Efficacy Outcomes at Week 16 in the Modified Intent-to-Treat Population.

| Variable | Placebo Every 2 wk (n = 52) | Lebrikizumab | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 125 mg Every 4 wk (n = 73) | 250 mg Every 4 wk (n = 80) | 250 mg Every 2 wk (n = 75) | ||

| Primary End Point | ||||

| LS mean (SD) % change from baseline in EASIa | −41.1 (56.5) | −62.3 (37.3) | −69.2 (38.3) | −72.1 (37.2) |

| P value vs placeboa | NA | .02 | .002 | <.001 |

| 95% CI of differencea | NA | −38.6 to −3.9 | −46.0 to −10.2 | −48.3 to −13.6 |

| Secondary End Points | ||||

| IGA 0/1 response, % | 15.3 | 26.6 | 33.7 | 44.6 |

| P value vs placebob | NA | .19 | .04 | .002 |

| EASI50, % | 45.8 | 66.4 | 77.0 | 81.0 |

| P value vs placebob | NA | .06 | .004 | <.001 |

| EASI75, % | 24.3 | 43.3 | 56.1 | 60.6 |

| P value vs placebob | NA | .06 | .002 | <.001 |

| EASI90, % | 11.4 | 26.1 | 36.1 | 44.0 |

| P value vs placebob | NA | .08 | .006 | <.001 |

| Pruritus NRS score LS mean (SD) % change from baselinec | 4.3 (55.6) | −35.9 (55.6) | −49.6 (55.6) | −60.6 (55.6) |

| P value vs placeboc | NA | .005 | <.001 | <.001 |

| 95% CI of differencec | NA | −67.9 to −12.5 | −81.4 to −26.3 | −93.0 to −36.8 |

| No. | 22 | 55 | 56 | 50 |

| Pruritus NRS score improvement of ≥4 points from baseline, % | 27.3 | 41.8 | 47.4 | 70.0 |

| P value vs placebod | NA | .24 | .11 | <.001 |

| No. | 22 | 55 | 57 | 50 |

| BSA involvement LS mean (SD) % change from baselinee | −41.8 (40.5) | −49.2 (40.5) | −60.5 (40.4) | −62.6 (40.6) |

| P value vs placeboe | NA | .45 | .06 | .04 |

| 95% CI of differencee | NA | −26.8 to 11.9 | −37.9 to 0.5 | −40.2 to −1.4 |

| No. | 24 | 59 | 62 | 59 |

| POEM total score mean (SD) change from baselinef | −5.8 (6.9) | −8.9 (7.4) | −11.4 (7.8) | −12.4 (6.9) |

| No. | 24 | 59 | 62 | 59 |

| DLQI mean (SD) change from baselinef | −5.9 (6.9) | −7.9 (6.7) | −9.2 (6.8) | −9.7 (7.1) |

| No. | 24 | 59 | 62 | 59 |

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index (range, 0 [no effect of skin disease on quality of life] to 30 [maximum effect on quality of life]); EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index (indicating ≥50%, ≥75%, or ≥90% improvement from baseline); IGA 0/1, Investigator’s Global Assessment (5-point scale, with 0 indicating clear and 1 indicating almost clear); LS, least squares; NA, not applicable; NRS, numeric rating scale; POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (range, 0 [clear] to 28 [very severe]).

From an analysis of covariance with a factor of treatment group and corresponding baseline EASI as the covariate. Values have been adjusted for multiple imputation. Missing data were imputed using Markov chain Monto Carlo methods.

From pairwise Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests. Missing data were imputed using Markov chain Monto Carlo methods. Patients with missing baseline values were not included in the analysis.

From an analysis of covariance with a factor of treatment group and corresponding baseline pruritus NRS score as the covariate. No imputations were made for missing data.

From pairwise Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests. No imputations were made for missing data.

From an analysis of covariance with a factor of treatment group and corresponding baseline BSA involvement as the covariate. No imputations were made for missing data.

In accord with the statistical analysis plan, comparisons of statistical significance were not performed. No imputations were made for missing data. Responses of “not done” were not included in summaries.

Secondary End Points

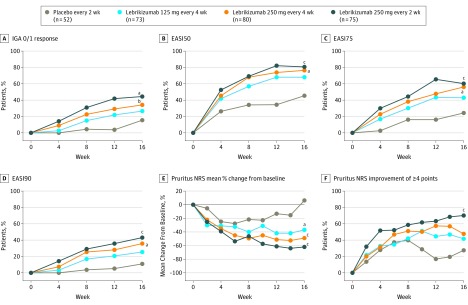

Statistically significantly more patients receiving the 250-mg lebrikizumab dose vs placebo achieved IGA 0/1 response, EASI50, EASI75, and EASI90 at week 16 (Table 2). Dose-dependent differences between placebo-treated patients and lebrikizumab-treated patients were seen as early as the first visit (week 4), with further improvement to week 16 (Figure 2). Lebrikizumab patients showed greater improvement vs placebo patients from baseline at week 16 in mean percentage BSA involvement, with statistically significant differences observed in the group receiving 250 mg every 2 weeks (Table 2).

Figure 2. Time Course of Response in the Modified Intent-to-Treat Population (Statistical Comparison at Week 16 Only).

A-D, Comparisons with placebo from pairwise Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests. Missing values were imputed using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. Patients with missing baseline values were not included in the analyses. After baseline up through week 16, visit summary statistics represent average values obtained by averaging the summary statistics generated from each imputed data set. E, Comparisons with placebo from least squares mean and contrast P values from an analysis of covariance with a factor of treatment group and corresponding baseline pruritus numeric rating scale score as the covariate. No imputations were made for missing data (patient numbers fluctuate at each visit). F, Comparisons with placebo from pairwise Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests. No imputations were made for missing data (patient numbers fluctuate at each visit). EASI indicates Eczema Area and Severity Index (indicating ≥50%, ≥75%, or ≥90% improvement from baseline); IGA 0/1, Investigator’s Global Assessment (5-point scale, with 0 indicating clear and 1 indicating almost clear); and NRS, numeric rating scale.

aP < .01 vs placebo.

bP < .05 vs placebo.

cP < .001 vs placebo.

Patient-Assessed Measures of Pruritus

Lebrikizumab groups showed dose-dependent, statistically significant improvement in least squares mean percentage change from baseline in pruritus NRS score at week 16 vs the placebo group (Table 2) using either no imputation method or MCMC imputation for missing data (eFigure 3A in Supplement 2). Improvements were observed throughout the trial to week 16 (Figure 2E, with statistical comparison at week 16 only). In addition, a greater proportion of lebrikizumab-treated patients vs placebo-treated patients achieved at least a 4-point improvement in pruritus NRS score from baseline at week 16, with statistically significant differences observed in the group receiving 250 mg every 2 weeks on both imputation methods performed (Table 2 [27.3% placebo vs 70.0% lebrikizumab, 250 mg every 2 weeks; P < .001, no imputation of missing data] and eFigure 3B in Supplement 2 [39.3% placebo vs 67.2% lebrikizumab, 250 mg every 2 weeks; P = .009, MCMC imputation]). Differences vs placebo-treated patients (4.5% [2 of 44]) in pruritus NRS score change of at least 4 points were seen as early as day 2 in the high-dose group: 6.3% (4 of 63), 5.6% (4 of 71), and 15.3% (9 of 59) for the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively. Improvements with lebrikizumab vs placebo were observed through week 16 (Figure 2F, with statistical comparison at week 16 only).

Efficacy in Patients With Prior Dupilumab Use

Of 16 patients self-reporting prior dupilumab use (4 placebo patients and 12 lebrikizumab patients [4, 3, and 5 in the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively]), 9 reported lack of efficacy with dupilumab. At week 16, compared with 0 of 4 placebo patients, 5 of 12 lebrikizumab patients with prior dupilumab use achieved EASI75, and 4 of 12 lebrikizumab patients achieved IGA 0/1 response.

Rescue Medication Use

Rescue medication use was approximately 3-fold greater among placebo-treated patients vs lebrikizumab-treated patients (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Across treatment groups, most patients used topical rescue medication only, with the exception of the group receiving lebrikizumab 250 mg every 4 weeks, in which more systemic rescue medication was used. Placebo-treated patients received topical rescue medication earlier than lebrikizumab-treated patients, and the duration of topical medication use was greater for placebo-treated patients vs lebrikizumab-treated patients. These findings suggest that TCS use would not have confounded our study results. Generally, outcomes of sensitivity analyses were consistent with those of the primary analysis and were similar regardless of rescue medication use (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Safety Assessments

Treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 24 of 52 placebo patients (46.2%) and in 42 of 73 (57.5%), 39 of 80 (48.8%), and 46 of 75 (61.3%) patients in the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively; most were mild to moderate and did not lead to trial discontinuation (Table 3). Low rates in TEAEs of clinical interest (injection site reactions, herpesvirus infections, and conjunctivitis) were reported. Infrequently, TEAEs led to discontinuation (in 1 of 52 placebo patients [1.9%] and in 9 of 228 lebrikizumab patients [3.9%]) (Table 3 and eTable 5 in Supplement 2). No deaths were reported during the study. Serious TEAEs were reported by 2 of 52 placebo patients (3.8%) (including peripheral edema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pulmonary embolism) and by 4 of 228 lebrikizumab patients (1.8%) (including chest pain, periprosthetic fracture, hernial eventration, and panic attack). No serious TEAEs were considered to be related to study drug, and none led to trial discontinuation.

Table 3. Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events (TEAEs) in the Safety Populationa.

| Variable | No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo Every 2 wk (n = 52) | Lebrikizumab | ||||

| 125 mg Every 4 wk (n = 73) | 250 mg Every 4 wk (n = 80) | 250 mg Every 2 wk (n = 75) | All (n = 228) | ||

| Patients reporting ≥1 TEAE | 24 (46.2) | 42 (57.5) | 39 (48.8) | 46 (61.3) | 127 (55.7) |

| No. of TEAEs | 61 | 104 | 115 | 143 | 362 |

| Patients reporting ≥1 serious TEAEs | 2 (3.8) | 2 (2.7) | 0 | 2 (2.7) | 4 (1.8) |

| No. of serious TEAEs | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patients who discontinued study because of TEAEs | 1 (1.9) | 2 (2.7) | 4 (5.0) | 3 (4.0) | 9 (3.9) |

| Maximum severity | |||||

| Mild | 12 (23.1) | 21 (28.8) | 12 (15.0) | 20 (26.7) | 53 (23.2) |

| Moderate | 8 (15.4) | 18 (24.7) | 25 (31.3) | 23 (30.7) | 66 (28.9) |

| Severe | 4 (7.7) | 3 (4.1) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (4.0) | 8 (3.5) |

| Strongest relationship to study drug | |||||

| Not related | 21 (40.4) | 34 (46.6) | 24 (30.0) | 31 (41.3) | 89 (39.0) |

| Related | 3 (5.8) | 8 (11.0) | 15 (18.8) | 15 (20.0) | 38 (16.7) |

| Common TEAEs reported in ≥5% in any lebrikizumab treatment group | |||||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 3 (5.8) | 6 (8.2) | 9 (11.3) | 2 (2.7) | 17 (7.5) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 2 (3.8) | 4 (5.5) | 2 (2.5) | 9 (12.0) | 15 (6.6) |

| Headache | 3 (5.8) | 3 (4.1) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (5.3) | 8 (3.5) |

| Injection site pain | 1 (1.9) | 0 | 3 (3.8) | 4 (5.3) | 7 (3.1) |

| Fatigue | 0 | 0 | 4 (5.0) | 0 | 4 (1.8) |

| TEAEs of clinical interest | |||||

| Injection site reactionsb | 1 (1.9) | 2 (2.7) | 4 (5.0) | 7 (9.3) | 13 (5.7) |

| Herpesvirus infectionsc | 2 (3.8) | 2 (2.7) | 4 (5.0) | 2 (2.7) | 8 (3.5) |

| Conjunctivitisd | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 3 (3.8) | 2 (2.7) | 6 (2.6) |

Treatment-emergent adverse events are those with an onset on or after the date of first study drug injection. Percentages are based on the number of patients in the safety population.

Includes the following injection site–related MedDRA (version 20.1; MedDRA MSSO) preferred terms: injection site pain, erythema, pruritus, edema, swelling, rash, dermatitis, infection, and reaction.

Includes the following MedDRA (version 20.1; MedDRA MSSO) preferred terms: oral herpes, herpes zoster, genital herpes, herpes simplex, and eczema herpeticum. Individual term rates were as follows: 0% (0 of 52) (placebo) vs 1.4% (1 of 73), 2.5% (2 of 80), and 1.3% (1 of 75) (for the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively) for oral herpes; 0% (0 of 52) (placebo) vs 0% (0 of 73), 2.5% (2 of 80), and 1.3% (1 of 75) (for the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively) for herpes zoster; 0% (0 of 52) (placebo) vs 1.4% (1 of 73), 0% (0 of 80), and 0% (0 of 75) (for the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively) for genital herpes; 1.9% (1 of 52) (placebo) vs 0% (0 of 73), 0% (0 of 80), and 0% (0 of 75) (for the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively) for herpes simplex; and 1.9% (1 of 52) (placebo) vs 0% (0 of 73), 0% (0 of 80), and 0% (0 of 75) (for the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively) for eczema herpeticum.

Includes the following MedDRA (version 20.1; MedDRA MSSO) preferred terms: conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis bacterial, and conjunctivitis allergic.

Common TEAEs (≥5% in any lebrikizumab group) included upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, headache, injection site pain, and fatigue (Table 3). Few lebrikizumab-treated patients reported TEAEs of clinical interest, namely, injection site reactions, herpesvirus infections, and conjunctivitis (Table 3). Low rates of conjunctivitis were reported (preferred terms by MedDRA, version 20.1; MedDRA MSSO: conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis bacterial, or conjunctivitis allergic), with no patients who received placebo reporting conjunctivitis vs 1.4% (1 of 73), 3.8% (3 of 80), and 2.7% (2 of 75) of patients in the 3 lebrikizumab groups, respectively. All of these conjunctivitis adverse events were moderate in severity, and none of these events led to discontinuation of study medication or the study; prior conjunctivitis history was not systematically captured. A similar rate of herpesvirus infections was reported in placebo patients and in all lebrikizumab-treated patients (Table 3). Injection site reactions were reported in less than 6% (13 of 228) of all lebrikizumab-treated patients.

No notable differences were observed between placebo patients and lebrikizumab patients with respect to physical examination results, vital signs, electrocardiogram measurements, and laboratory findings. Small increases in eosinophil counts were observed at week 4 in lebrikizumab patients; these changes were transient, and levels approached baseline values by week 16 (eFigure 4 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

During 16 weeks of treatment, lebrikizumab showed rapid, dose-dependent efficacy across a broad range of key AD clinical manifestations, including skin lesions, pruritus, and quality of life, in adult patients with moderate to severe AD not previously controlled by standard topical therapies. All 3 lebrikizumab groups showed dose-dependent, statistically significant improvement in the primary end point (mean percentage change in the EASI from baseline to week 16) vs placebo, which was supported by statistically significant improvements among the groups receiving 250 mg of lebrikizumab in secondary outcomes, including IGA 0/1 response, EASI50, EASI75, EASI90, pruritus NRS score, POEM total score, and DLQI.

Pruritus, which has substantial negative consequences for quality of life in AD,29 is regarded as the most burdensome symptom among patients with AD.30,31 Rapid, robust efficacy was observed with lebrikizumab on pruritus, which was measured daily by patients using an 11-point NRS. A reduction in itch severity was observed by day 2 in the high-dose lebrikizumab-treated patients. These data are consistent with preclinical evidence that IL-13 directly sensitizes sensory neurons to respond to pruritogens.13 The rapid onset of itch relief seen herein suggests that lebrikizumab may help ameliorate the substantial patient burden of itch in addition to concurrent improvement in clinical measures of disease severity.

The clinical success of dupilumab, an anti–IL-4Rα monoclonal antibody approved in the United States for treatment of adults and adolescents with moderate to severe AD,32 validated the importance of type 2 immune cytokine activation in AD pathophysiology.33,34 Dupilumab blocks downstream signaling of both IL-4 and IL-13, precluding the ability to discern which cytokine has a more central role in AD pathophysiology. The phase 2b data herein, prior successful investigational treatment of AD with lebrikizumab,21 and phase 2b data in AD with another monoclonal antibody acting on IL-13 (tralokinumab)35 suggest that IL-13 may be the central pathogenic mediator in AD. This hypothesis is supported by AD transcriptome data showing dominant expression of IL-13 cytokine, with much lower levels of IL-4 cytokine,36,37 as well as by the predominance of IL-13 and IL-13–producing cells in the circulation of patients with AD.14,38,39,40,41 These phase 2b data provide additional clinical support for the central role of IL-13 in AD pathophysiology and suggest that IL-13 inhibition alone may be sufficient for therapeutic responses in patients with AD.

Lebrikizumab was generally well tolerated, which is consistent with the safety profile observed in more than a dozen prior phase 2 and phase 3 lebrikizumab trials across multiple indications, during which more than 4500 patients received lebrikizumab.21,42,43,44,45,46,47 Most TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity and did not lead to discontinuation. Few lebrikizumab-treated patients reported TEAEs of clinical interest, including injection site reactions, herpesvirus infections, and conjunctivitis.

While the prevalence of conjunctivitis is increased among patients with AD vs healthy controls, dupilumab-induced conjunctivitis has emerged as a notable tolerability issue in dupilumab clinical trials and in real-world evidence from registries, ranging from 9% to 38%.48,49 Across all lebrikizumab AD studies, conjunctivitis rates have been low and similar to those in placebo-treated patients, with no clear dose-response pattern observed.21,47 Similar results have been reported in the phase 2b AD study of tralokinumab,35 suggesting that selective IL-13 blockade may not (or only minimally) increase risk of conjunctivitis in AD, which will be further clarified in larger phase 3 studies. It has been proposed that inhibition of IL-4 signaling through the type 1 receptor (IL-4Rα and common gamma chain) may trigger TH2 to TH1 polarization, which leads to interferon γ–mediated goblet cell apoptosis and reduction in mucin production50,51,52; this in turn leads to development of dry eye and conjunctivitis.53,54,55 Numerous investigations have been performed to investigate the risk factors for dupilumab-associated conjunctivitis given the high rates observed in clinical trials and real-world experience.56,57,58 Biopsy specimens from dupilumab-treated patients with AD who developed conjunctivitis showed substantial scarcity of intraepithelial goblet cells.59 Further data are needed to assess the mechanisms underlying dupilumab-induced conjunctivitis. Notably, rates of conjunctivitis were comparatively lower in our trial with lebrikizumab, no apparent dose-response relationship was observed, and no events resulted in discontinuation of study medication or the study.

Based on these phase 2b results and clinical data to date, lebrikizumab could be an important addition to the AD treatment landscape and a central therapeutic agent in the treatment paradigm. In addition to the rapid onset of lebrikizumab action (eg, itch relief by day 2) and the possibility of reduced risk for TEAEs of clinical interest (ie, injection site reactions, herpesvirus infections, and conjunctivitis) vs other biologic agents and small-molecule inhibitors in development, lebrikizumab may offer the possibility of convenient once-monthly dosing: improvements observed with once-monthly dosing were generally consistent with those of twice-monthly dosing. Indeed, the complex AD pathophysiology may warrant treatment options that target different cytokines and cytokine receptors to account for specific immunologic AD subtypes and a corresponding personalized treatment approach.12,60

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, AD is a chronic disease, and additional studies are needed to assess efficacy beyond 16 weeks, including the potential for less frequent maintenance dosing and maintenance of response over time. Second, the primary analysis did not account for TCS use. However, outcomes of sensitivity analyses were similar to those of the primary analyses and consistent regardless of rescue medication use, suggesting that TCS use did not confound results. Third, AD has high prevalence among adults and children in the United States,6 and this study only evaluated lebrikizumab in adults, limiting generalizability of our findings.

Conclusions

These data support the central role of IL-13 in AD pathophysiology. If these findings replicate in phase 3 studies, lebrikizumab may meaningfully advance the standard of care for moderate to severe AD. Taken together, the broad and robust improvements in AD clinical manifestations observed with lebrikizumab, along with its favorable safety profile, suggest that it may be an efficacious and well-tolerated treatment for moderate to severe AD. A follow-up phase 3 program25,26 was initiated in October 2019 to evaluate long-term efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, maintenance therapy regimens, and therapeutic use in younger patients.

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eTable 1. Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA)

eTable 2. Schedule of Assessments

eTable 3. Summary of Rescue Medication Use (Modified Intent-to-Treat Population)

eTable 4. Post Hoc Sensitivity Analysis (Modified Intent-to-Treat Population)

eTable 5. Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events Leading to Study Discontinuation Through End of Study (Safety Population)

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Percent Change in EASI (mITT Population; Statistical Comparison at Week 16 Only)

eFigure 3. Improvement on Pruritus NRS at Week 16 (mITT Population)

eFigure 4. Mean Change From Baseline (109/Liter) in Eosinophils (Safety Population)

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Deleanu D, Nedelea I. Biological therapies for atopic dermatitis: an update. Exp Ther Med. 2019;17(2):1061-1067. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman SR, Cox LS, Strowd LC, et al. The challenge of managing atopic dermatitis in the United States. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2019;12(2):83-93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim J, Kim BE, Leung DYM. Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis: clinical implications. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019;40(2):84-92. doi: 10.2500/aap.2019.40.4202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin M, Yoon J. From bench to clinic: the potential of therapeutic targeting of the IL-22 signaling pathway in atopic dermatitis. Immune Netw. 2018;18(6):e42. doi: 10.4110/in.2018.18.e42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunner PM, Guttman-Yassky E, Leung DY. The immunology of atopic dermatitis and its reversibility with broad-spectrum and targeted therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4S):S65-S76. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moyle M, Cevikbas F, Harden JL, Guttman-Yassky E. Understanding the immune landscape in atopic dermatitis: the era of biologics and emerging therapeutic approaches. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28(7):756-768. doi: 10.1111/exd.13911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raap U, Weißmantel S, Gehring M, Eisenberg AM, Kapp A, Fölster-Holst R. IL-31 significantly correlates with disease activity and Th2 cytokine levels in children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23(3):285-288. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01241.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raap U, Wichmann K, Bruder M, et al. Correlation of IL-31 serum levels with severity of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(2):421-423. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ezzat MH, Hasan ZE, Shaheen KY. Serum measurement of interleukin-31 (IL-31) in paediatric atopic dermatitis: elevated levels correlate with severity scoring. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(3):334-339. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trier AM, Kim BS. Cytokine modulation of atopic itch. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;54:7-12. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bieber T. Interleukin-13: targeting an underestimated cytokine in atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2020;75(1):54-62. doi: 10.1111/all.13954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czarnowicki T, He H, Krueger JG, Guttman-Yassky E. Atopic dermatitis endotypes and implications for targeted therapeutics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miron Y, Miller PE, Ghetti A, Ramos M, Hofland H, Cevikbas F. Neuronal responses elicited by interleukin-13 in human neurons. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(9):B8. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.06.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ungar B, Garcet S, Gonzalez J, et al. An integrated model of atopic dermatitis biomarkers highlights the systemic nature of the disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(3):603-613. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tazawa T, Sugiura H, Sugiura Y, Uehara M. Relative importance of IL-4 and IL-13 in lesional skin of atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2004;295(11):459-464. doi: 10.1007/s00403-004-0455-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choy DF, Hsu DK, Seshasayee D, et al. Comparative transcriptomic analyses of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis reveal shared neutrophilic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(6):1335-1143.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.06.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.La Grutta S, Richiusa P, Pizzolanti G, et al. CD4+IL-13+ cells in peripheral blood well correlates with the severity of atopic dermatitis in children. Allergy. 2005;60(3):391-395. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Czarnowicki T, Gonzalez J, Shemer A, et al. Severe atopic dermatitis is characterized by selective expansion of circulating TH2/TC2 and TH22/TC22, but not TH17/TC17, cells within the skin-homing T-cell population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(1):104-115.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czarnowicki T, He H, Leonard A, et al. Blood endotyping distinguishes the profile of vitiligo from that of other inflammatory and autoimmune skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(6):2095-2107. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou L, Leonard A, Pavel AB, et al. Age-specific changes in the molecular phenotype of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(1):144-156. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson EL, Flohr C, Eichenfield LF, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab (an anti–IL-13 monoclonal antibody) in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical corticosteroids: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase II trial (TREBLE). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(5):863-871.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download. Published December 2009. Accessed November 27, 2017.

- 23.Office of Medical Products and Tobacco, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; Office of Medical Products and Tobacco, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research . E6(R2) Good Clinical Practice: Integrated Addendum to ICH E6 (R1). https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/e6r2-good-clinical-practice-integrated-addendum-ich-e6r1. Published February 2018. Accessed March 7, 2018.

- 24.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ClinicalTrials.gov . Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Lebrikizumab in Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis. NCT04146363. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04146363?cond=NCT04146363&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed January 18, 2020.

- 26.ClinicalTrials.gov . Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Lebrikizumab in Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis. NCT04178967. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04178967?cond=NCT04178967&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed January 18, 2020.

- 27.Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M; EASI Evaluator Group . The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10(1):11-18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100102.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovener (Stockholm) Suppl. 1980;60(92):44-47. doi: 10.2340/00015555924447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li WQ, Sevetson E, Block JK, Qureshi AA. The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(1):26-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kido-Nakahara M, Furue M, Ulzii D, Nakahara T. Itch in atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37(1):113-122. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elmariah SB. Adjunctive management of itch in atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):373-394. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dupixent (dupilumab) [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis US LLC and Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2017.

- 33.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. ; SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators . Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335-2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):130-139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wollenberg A, Howell MD, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with tralokinumab, an anti–IL-13 mAb. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):135-141. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsoi LC, Rodriguez E, Degenhardt F, et al. Atopic dermatitis is an IL-13–dominant disease with greater molecular heterogeneity compared to psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(7):1480-1489. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suárez-Fariñas M, Ungar B, Noda S, et al. Alopecia areata profiling shows TH1, TH2, and IL-23 cytokine activation without parallel TH17/TH22 skewing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(5):1277-1287. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Czarnowicki T, Esaki H, Gonzalez J, et al. Early pediatric atopic dermatitis shows only a cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA)+ TH2/TH1 cell imbalance, whereas adults acquire CLA+ TH22/TC22 cell subsets. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(4):941-951.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunner PM, Suárez-Fariñas M, He H, et al. The atopic dermatitis blood signature is characterized by increases in inflammatory and cardiovascular risk proteins. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8707. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09207-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brunner PM, He H, Pavel AB, et al. The blood proteomic signature of early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis shows systemic inflammation and is distinct from adult long-standing disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(2):510-519. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He H, Li R, Choi S, et al. Increased cardiovascular and atherosclerosis markers in blood of older patients with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(1):70-78. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corren J, Lemanske RF, Hanania NA, et al. Lebrikizumab treatment in adults with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1088-1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanania NA, Noonan M, Corren J, et al. Lebrikizumab in moderate-to-severe asthma: pooled data from two randomised placebo-controlled studies. Thorax. 2015;70(8):748-756. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheerens H, Arron JR, Zheng Y, et al. The effects of lebrikizumab in patients with mild asthma following whole lung allergen challenge. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44(1):38-46. doi: 10.1111/cea.12220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noonan M, Korenblat P, Mosesova S, et al. Dose-ranging study of lebrikizumab in asthmatic patients not receiving inhaled steroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(3):567-574.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanania NA, Korenblat P, Chapman KR, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in patients with uncontrolled asthma (LAVOLTA I and LAVOLTA II): replicate, phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(10):781-796. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30265-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.ClinicalTrials.gov. A study to evaluate the safety of lebrikizumab compared to topical corticosteroids in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. NCT02465606. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02465606?term=NCT02465606&rank=1. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- 48.Thyssen JP, de Bruin-Weller MS, Paller AS, et al. Conjunctivitis in atopic dermatitis patients with and without dupilumab therapy: International Eczema Council survey and opinion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(7):1224-1231. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faiz S, Giovannelli J, Podevin C, et al. ; Groupe de Recherche sur l’Eczéma Atopique (GREAT), France . Effectiveness and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in a real-life French multicenter adult cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):143-151. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.García-Posadas L, Hodges RR, Diebold Y, Dartt DA. Context-dependent regulation of conjunctival goblet cell function by allergic mediators. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12162. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30002-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pflugfelder SC, Corrales RM, de Paiva CS. T helper cytokines in dry eye disease. Exp Eye Res. 2013;117:118-125. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tukler Henriksson J, Coursey TG, Corry DB, De Paiva CS, Pflugfelder SC. IL-13 stimulates proliferation and expression of mucin and immunomodulatory genes in cultured conjunctival goblet cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(8):4186-4197. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waldman RA, DeWane ME, Sloan SB, King B, Grant-Kels JM. Dupilumab ocular surface disease occurs predominantly in patients receiving dupilumab for atopic dermatitis: a multi-institution retrospective chart review [published online July 17, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maudinet A, Law-Koune S, Duretz C, Lasek A, Modiano P, Tran THC. Ocular surface diseases induced by dupilumab in severe atopic dermatitis. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8(3):485-490. doi: 10.1007/s40123-019-0191-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nahum Y, Mimouni M, Livny E, Bahar I, Hodak E, Leshem YA. Dupilumab-induced ocular surface disease (DIOSD) in patients with atopic dermatitis: clinical presentation, risk factors for development and outcomes of treatment with tacrolimus ointment [published online September 25, 2019]. Br J Ophthalmol. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-315010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287-2303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ou Z, Chen C, Chen A, Yang Y, Zhou W. Adverse events of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;54:303-310. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Treister AD, Kraff-Cooper C, Lio PA. Risk factors for dupilumab-associated conjunctivitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(10):1208-1211. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bakker DS, Ariens LFM, van Luijk C, et al. Goblet cell scarcity and conjunctival inflammation during treatment with dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(5):1248-1249. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brunner PM, Pavel AB, Khattri S, et al. Baseline IL-22 expression in atopic dermatitis patients stratifies tissue responses to fezakinumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):142-154. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eTable 1. Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA)

eTable 2. Schedule of Assessments

eTable 3. Summary of Rescue Medication Use (Modified Intent-to-Treat Population)

eTable 4. Post Hoc Sensitivity Analysis (Modified Intent-to-Treat Population)

eTable 5. Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events Leading to Study Discontinuation Through End of Study (Safety Population)

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Percent Change in EASI (mITT Population; Statistical Comparison at Week 16 Only)

eFigure 3. Improvement on Pruritus NRS at Week 16 (mITT Population)

eFigure 4. Mean Change From Baseline (109/Liter) in Eosinophils (Safety Population)

Data Sharing Statement