Abstract

Background and Aims

Crohn’s disease [CD] is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract characterised by alternating periods of exacerbation and remission. We hypothesised that changes in the gut microbiome are associated with CD exacerbations, and therefore aimed to correlate multiple gut microbiome features to CD disease activity.

Methods

Faecal microbiome data generated using whole-genome metagenomic shotgun sequencing of 196 CD patients were of obtained from the 1000IBD cohort [one sample per patient]. Patient disease activity status at time of sampling was determined by re-assessing clinical records 3 years after faecal sample production. Faecal samples were designated as taken ‘in an exacerbation’ or ‘in remission’. Samples taken ‘in remission’ were further categorised as ‘before the next exacerbation’ or ‘after the last exacerbation’, based on the exacerbation closest in time to the faecal production date. CD activity was correlated with gut microbial composition and predicted functional pathways via logistic regressions using MaAsLin software.

Results

In total, 105 bacterial pathways were decreased during CD exacerbation (false-discovery rate [FDR] <0.1) in comparison with the gut microbiome of patients both before and after an exacerbation. Most of these decreased pathways exert anti-inflammatory properties facilitating the biosynthesis and fermentation of various amino acids [tryptophan, methionine, and arginine], vitamins [riboflavin and thiamine], and short-chain fatty acids [SCFAs].

Conclusions

CD exacerbations are associated with a decrease in microbial genes involved in the biosynthesis of the anti-inflammatory mediators riboflavin, thiamine, and folate, and SCFAs, suggesting that increasing the intestinal abundances of these mediators might provide new treatment opportunities. These results were generated using bioinformatic analyses of cross-sectional data and need to be replicated using time-series and wet lab experiments.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease activity, faecal microbiome, whole-genome metagenomic shotgun sequencing

1. Background

Inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal [GI] tract that is characterised by alternating periods of exacerbation [active disease] and remission [quiescent disease].1,2 IBD comprises ulcerative colitis [UC] and Crohn’s disease [CD]; in UC, inflammation is confined to the mucosal layer of the colon, whereas in CD, inflammation can pervade every layer at any site of the GI tract.1,2 Although the factors that cause the development and onset of IBD are increasingly understood,1–4 the factors that influence the dynamics of disease activity have yet to be elucidated. A growing body of evidence, however, suggests that changes in the gut microbiome could be associated with an exacerbation of IBD.5–8 The identification of gut microbiome features associated with disease activity could thus provide novel targets for early phase intervention aimed at preventing the development of full-blown active disease or at maintaining IBD patients in a quiescent phase.

Over the past few years, a number of studies using sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene have compared the bacterial compositions in patients with active and quiescent disease, but these studies have produced conflicting results.9–15 A major limitation of 16S rRNA sequencing, however, is that it only describes which bacteria are present, not what they do. In contrast, whole-genome metagenomic sequencing can be used to predict the activity of microbial metabolic pathways, and this is information that might be more informative.16,17

In previous analyses by our group,4,18 only a small number of associations between individual measures of disease activity—i.e. HarveyBradshaw Index [HBI], faecal calprotectin [FC] and C-reactive protein [CRP] levels—and the gut microbiome were detected.

In this study, we aimed to better understand the role of the gut microbiome in disease activity in CD by analysing many different aspects of the gut microbiome, including microbial diversity, composition, the presence of genes involved in bacterial virulence, bacterial growth rates and microbial metabolic pathways in 196 CD patients, and comparing the results between patients with active and quiescent disease. Only one microbiome profile was available per patient, but because these patients were all clinically followed for several years after faecal sample production, we were able to calculate the number of days between stool sampling and nearest onset of disease activity. This allowed us to create a single virtual timeline of CD activity and to group patients into ‘before’, ‘during’, and ‘after’ exacerbation categories, which in turn allowed us to discover microbial features associated with CD activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study participants: clinical characteristics

2.1.1. 1000IBD cohort and informed consent

The 1000IBD cohort consists of more than 1000 IBD patients. The cohort has been described previously19 and originates from the specialised IBD Center of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of the University Medical Center Groningen [UMCG] in Groningen, The Netherlands. The 196 CD patients included in this study, and their corresponding metagenomic sequenced stool samples, all met study inclusion criteria [Supplementary material 1, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the UMCG [IRB number 2008.338].4 More information on the 1000IBD cohort can be found at [https://1000IBD.org].

2.1.2. Clinical characteristics, medication use, and dietary patterns

Extensive clinical phenotypes were documented for each CD patient in the study, including disease location, medication use at time of sampling, presence of perianal disease, previous surgery, stricturing phenotype, disease duration [indicated by the number of years since the Crohn’s disease diagnosis], CRP levels, and calprotectin levels. All these factors were measured around the time of faecal sampling. In addition, each patient filled in a Food Frequency Questionnaire [FFQ]19 at the time of faecal sampling, which recorded their food intake in the previous month. The FFQ answers were then transformed to grams/day in 25 food groups.

2.1.3. Definition of disease activity: exacerbation or remission

Electronic health records containing prospectively collected data on study participants were reviewed to determine disease activity status. Defining whether a patient with CD has an exacerbation can be difficult because individual clinical disease activity scores and biomarkers often do not correctly capture CD activity.20–27 Subjective disease activity scores rely heavily upon an increase in defaecation frequency and subjective abdominal complaints to determine disease activity. Biomarkers like faecal calprotectin [FC] show a highest sensitivity of 0.80 and specificity of 0.82 in inflammatory bowel disease [cut-off 250 µg/g],24 but FC does not detect ileal inflammation very well and is therefore less reliable in Crohn’s disease than in ulcerative colitis.28 Other biomarkers like CRP can also increase due to other causes, such as Clostridium difficile infections.29–31 To determine whether there is an exacerbation, a gastroenterologist will often take all these measures into account, as well as the outcome of a colonoscopy [if performed], the patient’s medical history, and the results of tests to exclude infectious enteritis. Therefore, in this study, a CD exacerbation was defined based on a combination of the following criteria:

i] An increase in the occurrence of IBD-associated gastrointestinal complaints that could not be attributed to other concurrent GI diseases, i.e., severe abdominal pain and cramping, increase in stool frequency, decrease in stool consistency, bloody diarrhoea, and/or malaise necessitating consecutive CD treatment adjustment or intensification.

-

ii] Interpretation by the treating physician based on a combination of the following criteria:

unplanned visits to the outpatient clinic due to typical patient complaints;

changes in IBD-associated biomarkers [calprotectin >200 μg/g faeces, CRP >5 mg/L] in a patient with typical complaints that could not be explained otherwise;

necessity of increasing dose and/or type of anti-IBD medication;

active inflammation seen during endoscopy;

active inflammation confirmed in a pathology report of gut biopsies.

2.1.4. Determination of disease activity status at the time of sampling

The dates of onset and recovery from recorded CD exacerbations were determined relative to the faecal sample production date. Faecal samples were thereby classified as taken ‘in an exacerbation’ or ‘in remission’. Samples ‘in remission’ were further categorised as ‘before the next exacerbation’ or ‘after the last exacerbation’. In addition, time to nearest disease exacerbation was recorded for all samples, defined as ‘days until next exacerbation’ or ‘days since last exacerbation’. When there were multiple recorded exacerbations, the closest exacerbation relative to the faecal production date was used to determine the disease activity.

2.2. Stool sampling and analysis of gut microbiome

Gut microbiome taxonomic compositions and functional profiles, bacterial growth rates, and abundances of virulence factor genes were determined as previously described.18

2.2.1. Sample collection and microbial DNA isolation

Patients produced and froze [-20°C] a stool sample at home. Frozen samples were then transported on dry ice to the UMCG and stored at -80°C. Microbial DNA was extracted from faecal samples using the Qiagen Allprep DNA/RNA Mini Kit [cat # 380204] with the addition of mechanical lysis.

2.2.2. Sequencing of microbial DNA

Metagenomic shotgun sequencing of microbial DNA was performed at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT in Cambridge, MA, USA, using the HiSeq platform. For genomic library preparation, the Nextera XT Library preparation Kit was used.

2.2.3. Quality control and determination of microbiome parameters

Trimmomatic [v.0.32]32 was used to remove adapters and trim the ends of metagenomic reads, and samples with a read depth below 10 million reads were removed. Cleaned metagenomic reads were processed using a previously published pipeline.18 In brief: a. taxonomic compositions were determined by aligning reads to the reference database RefSeq NCBI database33 [accession date: June 3, 2016] using the software tools Kraken34 and Bracken35; b. functional pathways were determined using HUMAnN2 [v.0.4.0] [http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/humann2] and families were grouped into pathways using multi-organism database MetaCyc36; c. abundances of genes encoding virulence factors were determined by aligning reads to the Virulence Factor Database37 using DIAMOND [version 0.8.2.]38; and d. bacterial growth rates were estimated using a previously described peak-to-trough ratio algorithm.39 Microbiome features present in at least 25% of samples were tested.

2.3. Statistical analysis

2.3.1. Summary statistics

We tested if the clinical characteristics, dietary patterns, Shannon Index and gene richness, and BrayCurtis distances [i.e., the inter-individual diversity or β-diversities] [Supplementary material 2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online] differed significantly between patient groups [‘in remission’ vs ‘in an exacerbation’ and ‘before the next exacerbation’ vs ‘in exacerbation’ vs ‘after the last exacerbation’]. The chi square test was used for binary phenotypes and the WilcoxonMannWhitney U test was used for continuous phenotypes. The BenjaminiHochberg method was used to calculate the false-discovery rate [FDR] for multiple testing. An FDR <0.1 was considered statistically significant. The proportion of explained variance on β-diversity was calculated for each clinical characteristic using the ADONIS function in R [Table S2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

2.3.2. Covariates

Models were constructed considering the covariates: age, sex, read depth, body mass index [BMI], disease location, use of PPI, and use of antibiotics 3 months before sampling, all of which are known to influence the gut microbiome. The dietary covariate ‘pre-prepared meals’ differed significantly between groups [Table 1] and was added to the models. The use of steroids differed significantly between groups [p = 0.000, chi square test], but was also correlated with disease activity [rho = 0.47, p = 0.000]. Since the correlation between independent variables—collinearity—is hard to take into account into the model, we did not take steroid use into account in the linear models. However, for transparency, we have added analyses with a correction for steroid use.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of CD patients corresponding to faecal samples.

| Before exacerbation | In exacerbation | After exacerbation | Remission [total] | Remission- exacerbation | Before-during | During-after | Remission- exacerbation | Before-during | During-after | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average [SD] or count [%] | Before + after | p-value | p-value | p-value | FDR | FDR | FDR | |||

| Number of samples [n] | 34 | 24 | 138 | 172 | ||||||

| Sequence read depth [SD] | 23097318 [7955650] | 23507652 [7521848] | 22252064 [7747729] | 22419149 [7773052] | 0.5503 | 0.9438 | 0.478 | 0,841594557 | 1 | 0,734071429 |

| Sex [F/M] [%] | 24/10 [71/29%] | 15/9 [63/37%] | 93/45 [67/33%] | 117/55 [68/32%] | 0.7579 | 0.7171 | 0.8145 | 0,880802703 | 0,971554839 | 0,931937126 |

| Age [SD] | 37.1 [11.5] | 42.0 [16.7] | 40.4 [13.9] | 39.7 [13.5] | 0.6447 | 0.372 | 0.7664 | 0,841594557 | 0,898333333 | 0,915422222 |

| BMI [SD] | 25.1 [5.9] | 23.3 [3.8] | 24.8 [4.8] | 24.8 [5.0] | 0.3024 | 0.4071 | 0.3097 | 0,732228571 | 0,899905263 | 0,579004348 |

| Disease location [MontrealL] | 0.6112 | 0.942 | 0.4623 | 0,841594557 | 1 | 0,734071429 | ||||

| Colon [%] | 4 [12%] | 3 [12%] | 33 [24%] | 37 [21%] | ||||||

| Ileum [%] | 13 [38%] | 10 [42%] | 52 [38%] | 65 [37%] | ||||||

| Both [%] | 17 [50%] | 11 [46%] | 53 [38%] | 70 [42%] | ||||||

| Disease duration [SD] | 10.3 [7.7] | 11.8 [11.6] | 12.7 [8.7] | 12.2 [8.5] | 0.3576 | 1.0 | 0.2607 | 0,732228571 | 1 | 0,579004348 |

| Behaviour [MontrealB] | 0.0765 | 0.2680 | 0.0783 | 0,4111875 | 0,865846154 | 0,3741 | ||||

| B1: no stric/pen | 19 [56%] | 11 [46%] | 78 [57%] | 97 [57%] | ||||||

| B2: stricturing [stric] [%] | 10 [29%] | 11 [46%] | 42 [30%] | 52 [30%] | ||||||

| B3: penetrating [pen] [%] | 5 [15%] | 2 [8%] | 18 [13%] | 23 [13%] | ||||||

| Presence perianal disease [y/n] [%] | 10/24 [29/71%] | 7/17 [29/71%] | 42/96 [30/70%] | 52/120 [30/70%] | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ileocaecal resections [y/n] [%] | 16/18 [47/53%] | 9/15 [37/63%] | 48/90 [35/65%] | 64/108 [37/63%] | 1.0 | 0.5862 | 0.8271 | 1 | 0,971554839 | 0,931937126 |

| Mesalazines [y/n] | 3/31 [9/91%] | 3/21 [13/87%] | 8/130 [6/94%] | 11/161 [6/94%] | 0.3867 | 0.6838 | 0.2104 | 0,746136 | 0,971554839 | 0,579004348 |

| Steroids [y/n] | 2/32 [6/94%] | 16/8 [67/33%] | 18/120 [13/87%] | 20/152 [12/88%] | 0.00000001801 | 0.0000009434 | 0.0000001181 | 7,74E-07* | 3,96E-05* | 5,08E-06* |

| Immunosuppressants [y/n] | 10/24 [29/71%] | 12/12 [50/50%] | 71/67 [51/49%] | 81/91 [47/53%] | 0.1442 | 0.3232 | 0.062 | 0,577763048 | 0,898333333 | 0,3741 |

| TNF-antagonist [y/n] | 9/25 [26/74%] | 6/18 [25/75%] | 59/79 [43/57%] | 68/104 [40/60%] | 0.1863 | 1.0 | 0.1182 | 0,667575 | 1 | 0,50826 |

| Biologicals [y/n] | 1/33 [3/97%] | 0/24 [0/100%] | 0/138 [0/100%] | 1/171 [1/99%] | 1.0 | NA | 1.0 | 1 | NA | 1 |

| Antibiotic use [y/n] [%] | 8/26 [24/76%] | 7/17 [29/71%] | 26/112 [19/81%] | 34/138 [20/80%] | 0.4338 | 0.7571 | 0.2704 | 0,746136 | 0,985597707 | 0,579004348 |

| PPI use [y/n] [%] | 8/26 [24/76%] | 11/13 [46/54%] | 31/107 [22/78%] | 39/133 [23/77%] | 0.02399 | 0.134 | 0.02339 | 0,2578925 | 0,621350952 | 0,2514425 |

| Calprotectin [mg/g] | 412 [493.1] | 514.2 [780.6] | 309.2 [523.0] | 329.4 [517.3] | 0.2494 | 0.903 | 0.1703 | 0,732228571 | 1 | 0,579004348 |

| CRP [mg/L] | 6.4 [9.3] | 9.1 [17.4] | 3.9 [8.0] | 4.4 [8.3] | 0.4837 | 0.385 | 0.2563 | 0,770337037 | 0,898333333 | 0,579004348 |

| Diet | ||||||||||

| Group_breads | 114.7 [66.6] | 149.4 [105.9] | 129.6 [86.7] | 126.6 [83.1] | 0,73 | 0,84 | 0,71 | 0,868038952 | 0,985597707 | 0,87555936 |

| Group_cereals | 3.2 [9.2] | 4.0 [9.1] | 4.7 [10.7] | 4.4 [10.4] | 0,7 | 0,35 | 0,85 | 0,854801233 | 0,898333333 | 0,931937126 |

| Group_vegetables | 91.2 [61.7] | 102.7 [68.0] | 101.7 [83.9] | 99.6 [79.8] | 0,95 | 0,67 | 0,96 | 1 | 0,971554839 | 1 |

| Group_fruits | 234.6 [252.6] | 233.9 [156.4] | 226.2 [213.1] | 227.9 [220.9] | 0,67 | 0,69 | 0,68 | 0,841594557 | 0,971554839 | 0,87555936 |

| Group_nuts | 9.4 [13.4] | 7.8 [9.8] | 10.8 [19.7] | 10.5 [18.5] | 0,41 | 0,37 | 0,46 | 0,746136 | 0,898333333 | 0,734071429 |

| Group_legumes | 7.1 [16.3] | 18.5 [57.8] | 8.7 [16.3] | 8.4 [16.3] | 0,87 | 0,52 | 1 | 0,963543775 | 0,971554839 | 1 |

| Group_alcohol | 60.6 [117.2] | 47.4 [111.3] | 57.7 [119.0] | 58.3 [118.3] | 0,35 | 0,71 | 0,3 | 0,732228571 | 0,971554839 | 0,579004348 |

| Group_cheese | 22.7 [23.7] | 21.7 [19.4] | 27.1 [36.3] | 26.2 [34.1] | 0,48 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,770337037 | 0,971554839 | 0,744807349 |

| Group_coffee | 261.7 [298.8] | 391.2 [281.5] | 295.3 [265.6] | 288.4 [272.1] | 0,27 | 0,15 | 0,37 | 0,732228571 | 0,621350952 | 0,659469673 |

| Group_dairy | 150.8 [144.9] | 287.4 [213.0] | 241.3 [245.9] | 222.8 [231.5] | 0,1 | 0,01 | 0,22 | 0,477909736 | 0,109827468 | 0,579004348 |

| Group_eggs | 10.0 [8.2] | 17.5 [16.6] | 13.7 [12.9] | 12.9 [12.2] | 0,43 | 0,21 | 0,56 | 0,746136 | 0,730956139 | 0,80696255 |

| Group_fish | 10.4 [13.2] | 13.0 [21.8] | 14.5 [15.1] | 13.6 [14.8] | 0,26 | 0,81 | 0,14 | 0,732228571 | 0,985597707 | 0,544001491 |

| Group_meat | 82.5 [39.5] | 101.0 [59.5] | 81.9 [42.8] | 82.0 [42.1] | 0,59 | 0,58 | 0,4 | 0,841594557 | 0,971554839 | 0,692889038 |

| Group_nonalcoholic_ drinks | 214.6 [232.4] | 220.6 [281.0] | 227.3 [251.9] | 224.8 [247.4] | 0,24 | 0,19 | 0,3 | 0,732228571 | 0,71505338 | 0,579004348 |

| Group_pasta | 16.3 [14.1] | 22.7 [22.7] | 18.4 [19.5] | 18.0 [18.5] | 0,64 | 0,78 | 0,63 | 0,841594557 | 0,985597707 | 0,847562414 |

| Group_pastry | 19.8 [13.8] | 34.9 [26.0] | 28.6 [26.9] | 26.8 [25.0] | 0,15 | 0,09 | 0,21 | 0,577763048 | 0,529054133 | 0,579004348 |

| Group_potatoes | 79.0 [61.1] | 102.8 [96.1] | 79.7 [64.3] | 79.5 [63.5] | 0,33 | 0,84 | 0,25 | 0,732228571 | 0,985597707 | 0,579004348 |

| Group_prepared_meal | 45.4 [40.7] | 23.1 [22.8] | 53.0 [60.3] | 51.5 [56.8] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,041115329* | 0,076656236* | 0,071313048* |

| Group_rice | 18.9 [20.9] | 18.5 [24.1] | 25.4 [59.3] | 24.1 [53.8] | 0,33 | 0,54 | 0,31 | 0,732228571 | 0,971554839 | 0,579004348 |

| Group_sauces | 14.6 [11.5] | 9.8 [10.1] | 16.8 [20.4] | 16.4 [19.0] | 0,01 | 0,01 | 0,02 | 0,138066122 | 0,138317908 | 0,216719753 |

| Group_savoury_snacks | 19.8 [18.5] | 18.7 [27.6] | 19.5 [20.3] | 19.6 [19.9] | 0,05 | 0,06 | 0,06 | 0,338327564 | 0,385487332 | 0,3741 |

| Group_soup | 40.0 [46.2] | 43.0 [39.4] | 49.5 [67.5] | 47.6 [63.7] | 0,66 | 0,61 | 0,71 | 0,841594557 | 0,971554839 | 0,87555936 |

| Group_spreads | 20.4 [22.2] | 30.6 [25.1] | 24.0 [31.7] | 23.2 [30.0] | 0,07 | 0,14 | 0,07 | 0,4111875 | 0,621350952 | 0,3741 |

| Group_sugar_sweets | 30.9 [27.1] | 53.7 [35.1] | 42.4 [50.7] | 40.0 [47.1] | 0,04 | 0,02 | 0,06 | 0,338327564 | 0,207149907 | 0,3741 |

| Group_tea | 198.1 [221.0] | 268.4 [250.3] | 293.6 [279.3] | 274.1 [270.6] | 0,83 | 0,49 | 0,63 | 0,940391785 | 0,971554839 | 0,847562414 |

*Significantly different. SD, standard deviation; FDR, false-discovery rate; F/M, female/male; BMI, bodymass index; stric, sricturing; pen, penetrating; y/n, yes/no; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; CRP, C-reactive protein.

2.3.3. Categorical analyses: before, during and after an exacerbation

Using the statistical software MaAsLin,8 we compared gut microbial features [relative abundances of species and functional pathways, abundances of virulence factors, and growth rate ratios] between: i. patients in an exacerbation versus patients in remission; ii. patients before versus in an exacerbation; and iii. patients in versus after an exacerbation. The MaAslin boosting step was turned off to ensure all independent variables were taken into account. Taxonomy and pathway relative abundances were arcsine square-root transformed. Zero inflation was considered in all tests except for growth rates. An FDR of 0.1 was used as a cut-off value for statistical significance. The function intersect in R [‘base’-package] was used to find microbiome features that were either both significantly decreased or increased before and after an exacerbation, as compared with during an exacerbation.

2.3.4. Linear analyses: 6 months before and after exacerbations

To test whether the microbiome can be used to monitor CD disease activity, features were linearly associated to the time to the temporally closest CD exacerbation in days. We hypothesised that if microbiota have pathogenic significance in CD, microbiome changes precede changes in disease activity. For this, an arbitrarily chosen period of 6 months was used. This meant that patients who had an exacerbation within 6 months of sampling were included in these analyses. Associations were performed using general linear models in MaAsLin, with the parameters specified above. The R function intersect was used to identify microbiome features that, in an inverse direction, shifted in the days preceding the onset of and restored quiescent balance after an exacerbation. Scripts used to perform data analyses are available at: [https://github.com/WeersmaLabIBD/Microbiome/blob/master/Protocol_ActivityCD_Marjolein_Klaassen.md].

3. Results

3.1. Clinical characteristics

Our cohort consisted of 196 CD patients from whom a single stool sample was collected between 2012 and 2014. At time of sampling, 24 patients [12%] were having an exacerbation, 15 patients [8%] would have their next exacerbation within 6 months, and 19 patients [10%] had had their last exacerbation less than 6 months previously. In addition, 19 patients [10%] would have their next exacerbation more than 6 months after sampling, and 119 patients [70%] had had their last exacerbation more than 6 months before sampling [Table S1, available as Supplementary data as ECCO-JCC online]. The clinical characteristics, medication use, and dietary patterns of the different groups are presented in Table 1. Only PPI use, steroid use, and pre-prepared meals differed between groups, and these features were added to the models [see Methods section].

3.2. Grouping based on disease activity

We performed several analyses to check whether the stool samples could be grouped into ‘before’, ‘during’, and ‘after’ an exacerbation; ‘in exacerbation’ or ‘in remission’ and ‘6 months to the next exacerbation’; and ‘6 months since the last exacerbation’, without creating bias.

First, we divided the cohort into patients with CD: a. who would have their next exacerbation in more than 6 months [n = 9]; and b. those who would have their next exacerbation within 6 months [n = 25]; and into patients: c. who had their last exacerbation less than 6 months ago [n = 34]; and d. who had their last exacerbation more than 6 months ago [n = 104]. Next, we calculated the differences in inter-individual diversity in functional composition using Bray-Curtis distances, and found that the overall functional compositions of patients in groups a. and b. were similar [p = 0.8 and p = 0.5, respectively; Wilcoxon test]. This was also the case for the patients in groups c. and d. [p = 0.07 and p = 0.8, respectively, Wilcoxon test]. These results indicate that the time to an exacerbation, in both the groups ‘before’ and ‘after’ an exacerbation, is not of influence for the gut microbiome composition. Therefore patients with CD ‘before’ an exacerbation can be considered as a single group, as can the patients with CD ‘after’ an exacerbation.

Second, we combined [I] the patients who were in remission for longer than 6 months [groups b. and c.; n = 113] and [II] the patients who would have their next or had their last exacerbation within 6 months [groups a. and d.; n = 59]. Then we calculated the inter-individual diversity in functional composition using BrayCurtis distances and found that the overall functional composition between patients who are in remission for longer than 6 months have similar microbiomes to those in remission for less than 6 months [PCoA1 p = 0.7, Wilcoxon test].

Third, we tested whether the gut microbiomes of patients before and after an exacerbation are similar, or in other words, whether we can group the patients who had taken a sample before their next exacerbation [groups a. and b.] with the patients who had their sample taken after an exacerbation [groups c. and d.] into remission together. To test this, we calculated the difference in inter-individual diversity in functional composition using BrayCurtis distances, and found that the gut microbiome of patients before and after an exacerbation are similar [PCoA1 p = 0.4, PCoA2 p = 0.8, Wilcoxon test].

Last, we performed an ADONIS analysis to test the proportion of variance of the gut microbiome which can be explained by the number of days until an exacerbation, and found that days to an exacerbation did not explain a significant proportion of the variance in the gut microbiome [R2 = 0.006, FDR = 0.272, Table S2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

We therefore concluded that the patients before an exacerbation, after an exacerbation, and in remission can be grouped as single groups based on their similarities in gut microbiome composition, regardless of the days until an exacerbation.

3.3. Correlations between gut microbiome features and disease activity

3.3.1. Functional but not taxonomical composition is related to CD exacerbations

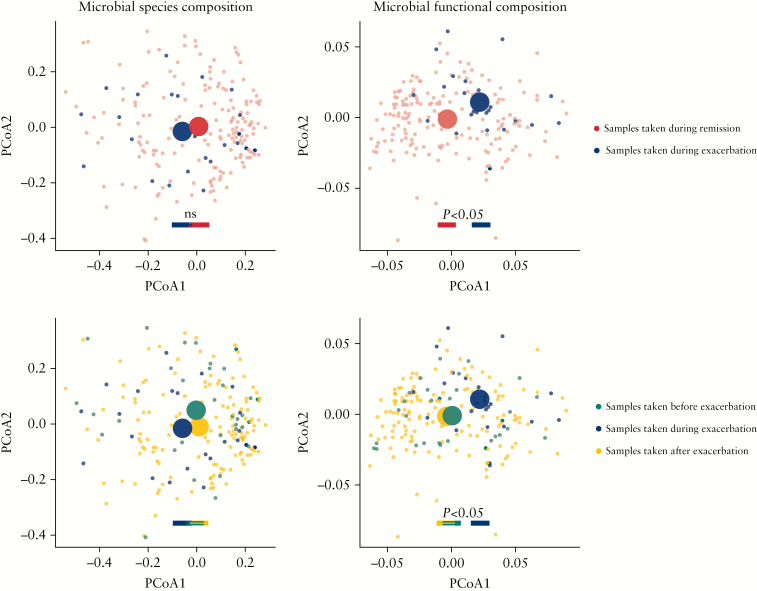

The gut microbiome of patients during an exacerbation had a similar overall species composition compared with the gut microbiome of patients before [PCoA1 p = 0.3, PCoA2 p = 0.09, Wilcoxon test] and after an exacerbation [PCoA1 p = 0.1, PCoA2 p = 0.8, Wilcoxon test]. There were no significant differences in taxonomic diversity between patients in an exacerbation and in remission [p = 0.88, Wilcoxon test], nor in patients before, in, or after an exacerbation [p = 0.46 and p = 0.68, respectively, Wilcoxon test].

In contrast, we did observe significant differences in microbial functional composition between patients during an exacerbation and patients in remission [PCoA1 p < 0.01, PCoA2 p = 0.04, Wilcoxon test]. Significant differences in function were also seen between patients before compared with during an exacerbation [PCoA1 p = 0.03, Wilcoxon test] and in patients during compared with after an exacerbation [PCoA1 p < 0.01, PCoA2 p = 0.04, Wilcoxon test] [Figure 1]. PcoA plots coloured on clinical characteristics can be found in [Table S3, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

Figure 1.

Microbial function but not taxonomy is related to CD exacerbations. Principal coordinate analyses [PCoA] of BrayCurtis distances, calculated for [I] taxonomy composition and [II] predicted functional composition. Each small-scale dot represents one faecal microbiome sample, coloured on the moment of faecal sampling being [a] during remission or in an exacerbation [I: PCoA1 p = 0.1, PCoA2 p = 0.6; II: PCoA1 p <0.01, PCoA2 p = 0.04, Wilcoxon test]; and [b] taken before or in an exacerbation [I: PCoA1 p = 0.3, PCoA2 p = 0.09, II: PCoA1 p = 0.03, Wilcoxon Test], or after an exacerbation [I: PCoA1 p = 0.1, PCoA2 p = 0.8; II: PCoA1 p <0.01, PCoA2 p = 0.04, Wilcoxon test], with each large-scale centroid representing the mean composition of each patient group. Significant differences were seen in predicted functional, however not in species, composition between patients with remissive and active Crohn’s disease [CD].

Disease activity could explain part of the variance in the gut microbiome function [R2 = 0.021, FDR = 0.007], but not of the gut microbiome taxonomical composition [R2 = 0.007, FDR = 0.007] [Table S2]. The gene richness of active patients was greater than the gene richness of patients with quiescent disease [p <0.01, Wilcoxon test] [before vs during exacerbation p = 0.03, during v. after exacerbation p = 0.01, respectively, Wilcoxon test].

3.3.2. Specific gut microbial pathways are decreased during a CD exacerbation

Relative abundances of 169 functional pathway genes were significantly different in CD patients in an exacerbation compared with patients in remission [FDR <0.1, logistic regression test]. The highest statistical significance was found for microbial pathways involved in the biosynthesis of all-trans-farnesol [PWY_6859, FDR = 0.007], L-methionine [PWY_5345, FDR = 0.008], and polyisoprenoid [POLYISOPRENSYN_PWY, FDR = 0.008], and these were all decreased during an exacerbation [Table S3].

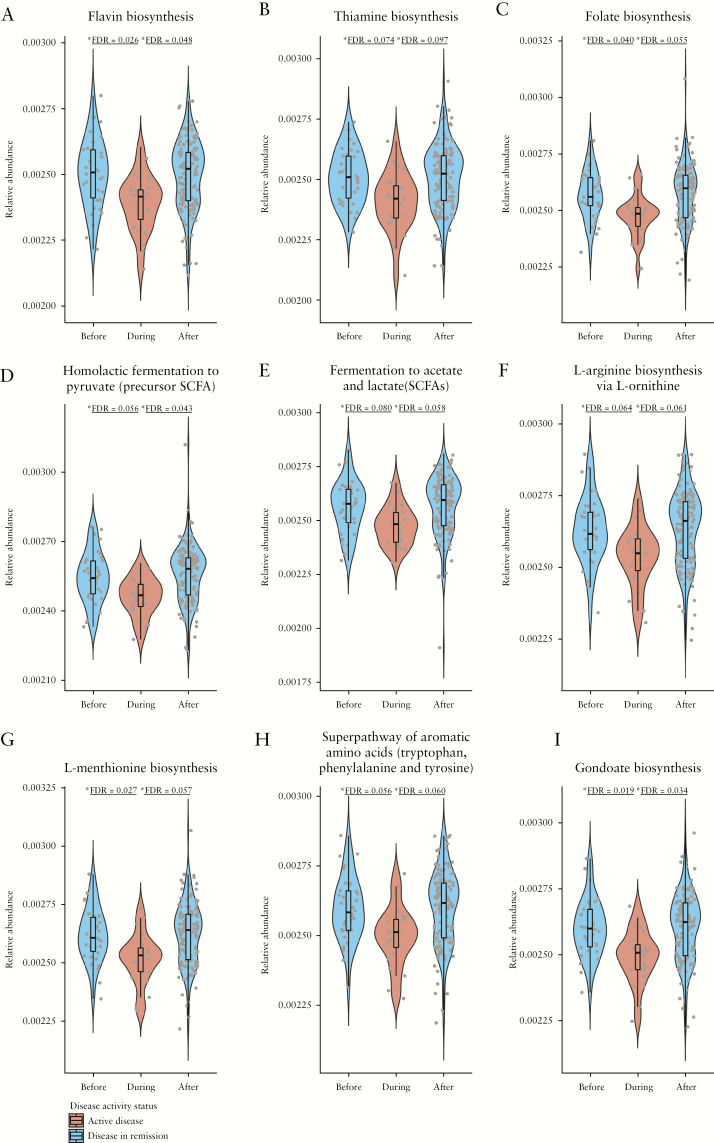

Furthermore, relative abundances of 105 pathway-encoding genes were significantly increased in CD patients both before and after an exacerbation [FDR <0.1, logistic regression test] [Table S4, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online] compared with CD patients in an exacerbation. Among these 105 genes: 14 encode pathways known to be involved in carbohydrate metabolism [five in biosynthesis and nine in degradation]; 24 pathways involved in biosynthesis of amino acids [L-tryptophan, L-methionine, L-lysine, L-phenylalanine, L-valine, L-isoleucine, L-arginine, L-threonine, L-histidine, and L-ornithine]; one involved in degradation of amino acids [L-phenylalanine]; five pathways involved in nucleosides and nucleotides biosynthesis; 10 involved in their degradation; 11 pathways involved in the biosynthesis of fatty acids [three in saturated and eight in unsaturated]; four pathways involved in the biosynthesis of the bacterial cell wall [three in peptidoglycan and one in UDP-N-acetylmuramoyl-pentapeptide]; four pathways involved in glycolysis; three pathways involved in the fermentation to short-chain fatty acids; and nine pathways involved in the biosynthesis of vitamins [thiamine, cobalamin, riboflavin, folate, and phosphopanthothenate] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Microbial pathway relative abundances before, during and after Crohn’s disease [CD] exacerbations. Violin plots representing relative abundances of genes encoding [a] flavin, [b] thiamine, and [c] folate biosynthesis, [d] homolactic fermentation to short-chain fatty acids [SCFAs], [e] fermentation to acetate and lactate [SCFAs], [f] L-arginine, [g] L-methionine, [h] cis-vaccenate, and [i] gondoate biosynthesis, in faecal samples taken before, during, and after CD exacerbations. To approximate the zero-inflated model used in the MaAsLin analyses (resulting in false-discovery rate [FDR] values), a y-limit >0 was used.

Despite its being correlated with disease activity [rho = 0.47, p = 0.000], when adding steroid use to the model, 54% of the pathways remain decreased during an exacerbation as compared with the total patients in remission [Table S12, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online], and 29% remained decreased compared with both before and after an exacerbation [Table S12].

We also investigated the differential abundance of genes encoding for virulence factors and the predicted growth dynamics, but found no significant differences between patients in a CD exacerbation and patients in remission, nor in patients before, in, and after an exacerbation [Tables S5–S7, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

3.3. Monitoring CD disease activity: the microbiome in the six months before and after an exacerbation

We next investigated whether the microbial features associated with an exacerbation also showed a linear correlation with the time [specified in days] before and after an exacerbation. Analyses were confined to patients who experienced an exacerbation in the 6 months before [n = 15] or after [n = 19] their faecal sample was collected.

The proportion of explained variance in both the taxonomic and functional composition of the variable ‘days to exacerbation’ was not significant [R = 0.004, FDR = 0.749 and R = 0.004, FDR = 0.749, respectively] [Table S2]. Therefore, correlations between proximity to an exacerbation and changes in the abundance of microbiome features were considered less reliable [Tables S8–S11, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

4. Discussion

In this cohort of CD patients, we compared the gut microbiome composition of patients in an exacerbation with the microbiome of patients before and patients after an exacerbation. In previous analyses of this cohort,4,18 few pathways were associated with the established individual parameters used to define disease activity [faecal calprotectin levels >200 mg/kg faeces or HBI >4].18 In this study, we were not able to link all of these pathways to active disease, which could potentially be explained by the fact that the use of different criteria to define active disease leads to a different grouping of patients with CD based on this disease activity. Furthermore, the effect sizes of the identified pathways could be relatively small. These differences indicate the importance of well defining active disease in the context of CD.

Moreover, a thorough review of the medical records in this study allowed us to use more than just a single marker for disease activity, since individual clinical markers (Crohn’s Disease Activity Index [CDAI], HBI) and biomarkers [CRP, faecal calprotectin] are often unreliable and show poor correlation.20–27 Although combining these factors with information from the endoscopy results, medication changes, and the gastroenterologist’s opinion could be considered unconventional, it does reflect how disease activity is determined in clinical practice. Therefore, we think the additional information could more reliably determine the occurrence of an exacerbation and the correlation with gut microbiome features.

We found that it is not taxonomic distributions but rather function of the microbiome that differs between active and quiescent CD patients. We found that genes encoding 105 microbial pathways were decreased during exacerbation, and these genes mostly exert anti-inflammatory properties by facilitating the biosynthesis and fermentation of various amino acids [tryptophan, methionine, and arginine], B vitamins [riboflavin and thiamine] and short-chain fatty acids [SCFAs]. Notably, all these functional pathways appeared to recover after an exacerbation.

We describe that abundances of genes involved in the fermentation of fibres to acetic acid [SCFA] and pyruvate [main precursor of SCFAs] are decreased during a CD exacerbation, whereas there were no differences in the consumption of fibre-rich foods between the CD patients in an exacerbation and CD patients in remission. This is in congruence with the previously described decreased gene abundance involved in the fermentation of fibres in active treatment-naïve patients.40 SCFAs are the main metabolic end products of microbial fermentation of undigested complex carbohydrates in the human colon. SCFAs induce tolerogenic and anti-inflammatory enterocyte phenotypes and maintain gut integrity by being the main energy source for enterocytes, by inducing downregulation of pro-inflammatory innate immune cells and their cytokines41–46 and upregulation of anti-inflammatory T regulatory cells,47–51 and by increasing the transcription of mucin genes in intestinal goblet cells.52,53 A role for SCFAs in controlling inflammation has already been shown in an experimental colitis model in mice, where supplemental dietary SCFAs attenuated colonic inflammation.54 Decreased abundances of intestinal SCFAs could play a role in intestinal inflammation during CD exacerbations.

We also found that microbial genes encoding the biosynthesis of the B vitamins thiamine [vitamin B1], riboflavin [vitamin B2], and folate [vitamin B9] are decreased during CD exacerbations, which is interesting given established links between these vitamins and reduced inflammation. Previous studies have shown that supplementation of riboflavin and thiamine reduces the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6.55–58 Riboflavin and thiamine have also been shown to intensify the anti-inflammatory activity of the corticosteroid anti-inflammatory drug dexamethasone.55 Riboflavin injections in mouse models also inhibit the febrile response induced by lipopolysaccharides [LPS].55 Microbe-derived riboflavin and folic acid have been described to activate mucosa-associated invariant T [MAIT]59,60 cells, and thereby control microbial infection of the gut. Taken together, all these lines of evidence indicate that decreases in the intestinal abundances of thiamine, riboflavin, and folate could be involved in sustaining a CD exacerbation.

An example of an overlapping pathway between this study and our recently published study18 is the decrease in the abundance of genes predicted to encode the biosynthesis of the amino acid L-arginine in CD patients compared with a general population cohort, as well as a decrease of these genes in CD patients in an exacerbation as compared to those in remission. Until this present study and our previous studies, disturbances have not been described in L-arginine, nor in the other amino acid L-tryptophan, in CD disease activity [Figure 2]. However, it has been observed in mice that a decrease in tryptophan metabolism results in deficient aryl hydrocarbon receptor [AHR] activation, leading to susceptibility to colitis.61 Colonic inflammation was reduced in these mice when they were administered a diet supplemented with synthetic AHR ligands.62 Moreover, arginine is known as the precursor in the synthesis of polyamines, which are the constituents of intercellular junctions of the gut epithelium, and is therefore of importance in maintaining the integrity of the gut.63,64 Decreases in L-tryptophan and L-arginine might play a role in intestinal inflammation during CD exacerbations.

Although we were able to observe many differences in functional profiles, we did not observe significant changes in species-level taxonomic composition, virulence content, or growth dynamics. Longitudinal profiling of the variation in microbial species composition65,66 has previously shown that species variation within the microbiome is mainly dominated by inter-individual effects. It is metabolic microbial pathways rather than taxonomy that are more conserved among individuals,66 and pathways might therefore be more appropriate for detecting how the influence of the microbiome mediates CD disease activity during a cross-sectional comparison between active and quiescent patients.16,17 Previous studies investigating differences in taxonomic composition between active and inactive disease showed inconsistent results.9–15 Collectively, these lines of evidence might explain the lack of identification of individual species associated with active and quiescent CD.

We have compared predicted functional pathways between remissive and active CD using microbial genomic information, but transcriptomic or metabolomic data might provide better insights into the gut environment. However, a recent paper that calculated the ratio between the metagenomic [DNA] and metatranscriptomic [RNA] abundances in stool samples of IBD patients65 found that the functional potential [DNA] is often proportional to the metatranscriptomic expression [RNA], indicating that the functional genomic estimations are likely to represent changes in microbial genetic expression.

We found that 29% of the patients in an exacerbation had used antibiotics in the 3 months previous to sampling. Even though this was not significantly different compared with the patients before and after an exacerbation [FDR = 0.986 and FDR = 0.579, respectively], we added this factor into our linear models because of the known effects of antibiotic use on gut microbiome composition. In addition, we performed the analyses both with and without steroid use as a covariate in the model, as oral steroid use was correlated with having an exacerbation. Since this correlation between independent variables is hard to take into account in the model, we argued that the main results should be derived from the analyses without steroid use in the model. In addition, our group has previously shown that the use of steroids has no effects on the composition of the gut microbiome.67 Nevertheless, we display both results in this study.

In our study, we aimed to derive gut microbiome dynamics in CD from cross-sectional data. We created a virtual timeline across all participants by assessing the time since the last exacerbation and the time to the next exacerbation, by re-analysing the medical records of the CD patients a few years after sampling. When performing these analyses, we assumed that uniform patterns could still be detected even with the known inter-individual gut microbiome variation. Categorical analyses [grouping patients into before, during, and after a flare] showed 105 pathways to be decreased during a flare, whereas linear analyses [number of days to next exacerbation, number of days since last exacerbation] did not show significant results, probably due to limited sample size.

We understand that the results of our bioinformatic analyses are less reliable than true time-series experiments and that the results of this study need to be replicated by future studies. However, we do believe that our results are a valuable contribution to the growing knowledge about the gut microbiome in CD, which will enable researchers to study the proposed mechanisms, including in cross-sectional designs. Thorough review of the medical records allowed us to use more than just a single marker for disease activity, since individual clinical markers [for example HBI] and biomarkers [CRP, faecal calprotectin] are often unreliable and show poor correlation. Although combining these factors with information from the endoscopy results, medication changes, and the gastroenterologist’s opinion could be considered unconventional, it does reflect how disease activity is determined in clinical practice. Therefore, we think the additional information could more reliably determine the occurrence of an exacerbation.

In conclusion, we identified pro-inflammatory differences in gut microbiome function during CD disease activity. This work identified roles for several compounds in ameliorating disease activity, including vitamins and amino acids that are already available as dietary supplements at the local drugstore and could thus easily be tested. Our results could therefore be used as novel targets for translational studies trying to modulate the function of the gut microbiome in an anti-inflammatory manner.

Funding

RKW, JF, and AZ are supported by VIDI grants [016.136.308, 864.13.013, 016.178.056] from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research [NWO]. RKW is also supported by a Diagnostics Grant from the Dutch Digestive Foundation [MLDS D16-14]. AZ holds a Rosalind Franklin fellowship from the University of Groningen and is supported by a European Research Council [ERC] starting grant [ERC-715772]. JF and AZ are further supported by a CardioVascular Onderzoek Nederland grant [IN-CONTROL CVON 2012-03]. CW is supported by a Spinoza award [NWO SPI 92-266], an ERC advanced grant [ERC-671274], a grant from the Nederlands’ Top Institute Food and Nutrition [GH001], the NWO Gravitation Netherlands Organ-on-Chip Initiative [024.003.001], the Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen Foundation [Norway], and the RuG investment agenda grant Personalized Health.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Author Contributions

FI and RKW designed the study. FI and VC collected extensive clinical phenotype data of the patients. MAYK reviewed patients’ electronic health records. AVV designed a pipeline to determine microbial profiles from raw metagenomic reads, and processed all samples using this pipeline. MAYK performed all statistical analyses. MAYK and FI wrote the manuscript. VC, AVV, RG, JF, HMD, GD, EAMF, CW, AZ, and RKW critically reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 2012;380:1590–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Manichanh C, Borruel N, Casellas F, Guarner F. The gut microbiota in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;9:599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rutgeerts P, Goboes K, Peeters M, et al. Effect of faecal stream diversion on recurrence of Crohn’s disease in the neoterminal ileum. Lancet 1991;338:771–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Imhann F, Vich Vila A, Bonder MJ, et al. Interplay of host genetics and gut microbiota underlying the onset and clinical presentation of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2018;67:108–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matsuoka K, Kanai T. The gut microbiota and inflammatory bowel disease. Semin Immunopathol 2015;37:47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, et al. ; International IBD Genetics Consortium [IIBDGC] Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2012;491: 119–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elson CO, Cong Y, McCracken VJ, Dimmitt RA, Lorenz RG, Weaver CT. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease reveal innate, adaptive, and regulatory mechanisms of host dialogue with the microbiota. Immunol Rev 2005;206:260–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morgan XC, Tickle TL, Sokol H, et al. Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol 2012;13:R79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wills ES, Jonkers DMAE, Savelkoul PH, Masclee AA, Pierik MJ, Penders J. Faecal microbial composition of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients in remission and subsequent exacerbation. PLoS One 2014;9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang W, Chen L, Zhou R, et al. Increased proportions of Bifidobacterium and the Lactobacillus group and loss of butyrate-producing bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Microbiol 2014;52:398–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seksik P, Rigottier-Gois L, Gramet G, et al. Alterations of the dominant faecal bacterial groups in patients with Crohn’s disease of the colon. Gut 2003;52:237–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Andoh A, Kuzuoka H, Tsujikawa T, et al. Multicenter analysis of faecal microbiota profiles in Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol 2012;47:1298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tedjo DI, Smolinska A, Savelkoul PH, et al. The faecal microbiota as a biomarker for disease activity in Crohn’s disease. Sci Rep 2016;6:35216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sokol H, Seksik P, Furet JP, et al. Low counts of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in colitis microbiota. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:1183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Halfvarson J, Brislawn CJ, Lamendella R, et al. Dynamics of the human gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol 2017;2. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Meyer F, Trimble WL, Chang EB, Handley KM. Functional predictions from inference and observation in sequence-based inflammatory bowel disease research. Genome Biol 2012. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Presley LL, Ye J, Li X, et al. Host-microbe relationships in inflammatory bowel disease detected by bacterial and metaproteomic analysis of the mucosal-luminal interface. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:409–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vich Vila A, Imhann F, Collij V, et al. Gut microbiota composition and functional changes in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Sci Transl Med 2018;10:eaap8914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spekhorst LM, Imhann F, Festen EAM, et al. ; Parelsnoer Institute [PSI] and the Dutch Initiative on Crohn and Colitis [ICC] Cohort profile: design and first results of the Dutch IBD Biobank: a prospective, nationwide biobank of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Foti PV, Farina R, Coronella M, et al. Crohn’s disease of the small bowel: evaluation of ileal inflammation by diffusion-weighted MR imaging and correlation with the Harvey-Bradshaw index. Radiol Med 2015;120:585–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crama-Bohbouth G, Pena AS, Biemond I, et al. Are activity indices helpful in assessing active intestinal inflammation in Crohn’s disease? Gut 1989;30:1236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jørgensen LGM, Fredholm L, Hyltoft Petersen P, Hey H, Munkholm P, Brandslund I. How accurate are clinical activity indices for scoring of disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]? Clin Chem Lab Med 2005;43:403–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zittan E, Kabakchiev B, Kelly OB, et al. Development of the Harvey-Bradshaw Index-pro [HBI-PRO] score to assess endoscopic disease activity in Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:5–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin J-F, Chen J-M, Zuo J-H, et al. Meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Costa F, Mumolo MG, Ceccarelli L, et al. Calprotectin is a stronger predictive marker of relapse in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2005;54:364–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miranda-García P, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Correlation between serological biomarkers and endoscopic activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;39:508–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sipponen T, Savilahti E, Kolho KL, Nuutinen H, Turunen U, Färkkilä M. Crohn’s disease activity assessed by faecal calprotectin and lactoferrin: correlation with Crohn’s disease activity index and endoscopic findings. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:40–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gecse KB, Brandse JF, van Wilpe S, et al. Impact of disease location on faecal calprotectin levels in Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2015;50:841–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wright JM, Adams SP, Gribble MJ, Bowie WR. Clostridium difficile in Crohn’s disease. Can J Surg 1984;27:435–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kurtz LE, Yang SS, Bank S. Clostridium difficile-associated small bowel enteritis after total proctocolectomy in a Crohn’s disease patient. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010;44:76–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim J, Kim H, Oh HJ, et al. Faecal calprotectin level reflects the severity of Clostridium difficile infection. Ann Lab Med 2017;37:53–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014;30:2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences [RefSeq]: a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35:D61–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wood DE, Salzberg SL. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol 2014;15:R46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lu J, Breitwieser FP, Thielen P, Salzberg SL. Bracken: estimating species abundance in metagenomics data. BioRxiv 2016. d https://doi.org/10.1101/051813. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Caspi R, Billington R, Ferrer L, et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:D471–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen L, Zheng D, Liu B, Yang J, Jin Q. VFDB 2016: hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis – 10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:D694–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 2015;12:59–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Korem T, Zeevi D, Suez J, et al. Growth dynamics of gut microbiota in health and disease inferred from single metagenomic samples. Science 2015;349:1101–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson LA, et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe 2014;15:382–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Usami M, Kishimoto K, Ohata A, et al. Butyrate and trichostatin A attenuate nuclear factor kappaB activation and tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion and increase prostaglandin E2 secretion in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Nutr Res 2008;28:321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Hatanaka E, Sato FT, Sampaio SC, Curi R. Suppressive effect of short-chain fatty acids on production of proinflammatory mediators by neutrophils. J Nutr Biochem 2011;22:849–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kendrick SFW, O’Boyle G, Mann J, et al. Acetate, the key modulator of inflammatory responses in acute alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2010;51:1988–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Singh N, Thangaraju M, Prasad PD, et al. Blockade of dendritic cell development by bacterial fermentation products butyrate and propionate through a transporter [Slc5a8]-dependent inhibition of histone deacetylases. J Biol Chem 2010;285:27601–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Yadava K, et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med 2014;20:159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chang PV, Hao L, Offermanns S, Medzhitov R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:2247–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tao R, de Zoeten EF, Ozkaynak E, et al. Deacetylase inhibition promotes the generation and function of regulatory T cells. Nat Med 2007;13:1299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 2013;504:446–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 2013;504:451–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science 2013;341:569–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thorburn AN, McKenzie CI, Shen S, et al. Evidence that asthma is a developmental origin disease influenced by maternal diet and bacterial metabolites. Nat Commun 2015;6:7320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Willemsen LE, Koetsier MA, van Deventer SJ, van Tol EA. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate epithelial mucin 2 expression through differential effects on prostaglandin E[1] and E[2] production by intestinal myofibroblasts. Gut 2003;52:1442–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gaudier E, Jarry A, Blottière HM, et al. Butyrate specifically modulates MUC gene expression in intestinal epithelial goblet cells deprived of glucose. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2004;287:G1168–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature 2009;461:1282–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Menezes RR, Godin AM, Rodrigues FF, et al. Thiamine and riboflavin inhibit production of cytokines and increase the anti-inflammatory activity of a corticosteroid in a chronic model of inflammation induced by complete Freund’s adjuvant. Pharmacol Rep 2017;69:1036–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bertollo CM, Oliveira AC, Rocha LT, Costa KA, Nascimento EB Jr, Coelho MM. Characterization of the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of riboflavin in different experimental models. Eur J Pharmacol 2006;547:184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Toyosawa T, Suzuki M, Kodama K, Araki S. Highly purified vitamin B2 presents a promising therapeutic strategy for sepsis and septic shock. Infect Immun 2004;72:1820–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Toyosawa T, Suzuki M, Kodama K, Araki S. Effects of intravenous infusion of highly purified vitamin B2 on lipopolysaccharide-induced shock and bacterial infection in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 2004;492:273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sakala IG, Kjer-Nielsen L, Eickhoff CS, et al. Functional heterogeneity and antimycobacterial effects of mouse mucosal-associated invariant T cells specific for riboflavin metabolites. J Immunol 2015;195:587–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brestoff JR, Artis D. Commensal bacteria at the interface of host metabolism and the immune system. Nat Immunol 2013;14:676–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lamas B, Richard ML, Sokol H. Caspase recruitment domain 9, microbiota, and tryptophan metabolism: dangerous liaisons in inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2017;20:243–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Li Y, Innocentin S, Withers DR, et al. Exogenous stimuli maintain intraepithelial lymphocytes via aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation. Cell 2011;147:629–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chen J, Rao JN, Zou T, et al. Polyamines are required for expression of Toll-like receptor 2 modulating intestinal epithelial barrier integrity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2007;293:G568–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Liu L, Guo X, Rao JN, et al. Polyamines regulate E-cadherin transcription through c-Myc modulating intestinal epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2009;296:C801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schirmer M, Franzosa EA, Lloyd-Price J, et al. Dynamics of metatranscription in the inflammatory bowel disease gut microbiome. Nat Microbiol 2018;3:337–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Huttenhower C; Human Microbiome Project Consortium Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012;486:207–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhernakova A, Kurilshikov A, Bonder MJ, et al. ; LifeLines cohort study Population-based metagenomics analysis reveals markers for gut microbiome composition and diversity. Science 2016;352:565–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.