Abstract

Simple Summary

Many Chinese-local chickens show slow-growing and low-producing performance, which is not conductive to the development of the poultry industry. The identification of thousands of indels in the last twenty years has helped us to make progress in animal genetics and breeding. Golgin subfamily B member 1 (GOLGB1) is located on chromosome 1 in chickens. Previous study showed that a large number of QTLs on the chicken chromosome 1 were related to the important economic traits. However, the biological function of GOLGB1 gene in chickens is still unclear. In this study, we detected a novel 65-bp indel in the fifth intron of the chicken GOLGB1 gene. Correlation analysis between the 65-bp indel and chicken growth and carcass traits was performed through a yellow chicken population, which is commercial. Results revealed that this 65-bp indel was significantly associated with chicken body weight, highly significantly associated with neck weight, abdominal fat weight, abdominal fat percentage, and the yellow index b of breast. These findings hinted that the 65-bp indel in GOLGB1 could be assigned to a molecular marker in chicken breeding and enhance production in the chicken industry.

Abstract

Golgin subfamily B member 1 (GOLGB1) gene encodes the coat protein 1 vesicle inhibiting factor, giantin. Previous study showed that mutations of the GOLGB1 gene are associated with dozens of human developmental disorders and diseases. However, the biological function of GOLGB1 gene in chicken is still unclear. In this study, we detected a novel 65-bp insertion/deletion (indel) polymorphism in the chicken GOLGB1 intron 5. Association of this indel with chicken growth and carcass traits was analyzed in a yellow chicken population. Results showed that this 65-bp indel was significantly associated with chicken body weight (p < 0.05), highly significantly associated with neck weight, abdominal fat weight, abdominal fat percentage and the yellow index b of breast (p < 0.01). Analysis of genetic parameters indicated that “I” was the predominant allele. Except for the yellow index b of breast, II genotype individuals had the best growth characteristics, by comparison with the ID genotype and DD genotype individuals. Moreover, the mRNA expression of GOLGB1 was detected in the liver tissue of chicken with different GOLGB1 genotypes, where the DD genotype displayed high expression levels. These findings hinted that the 65-bp indel in GOLGB1 could be assigned to a molecular marker in chicken breeding and enhance production in the chicken industry.

Keywords: chicken, GOLGB1, indel, growth and carcass traits

1. Introduction

Golgin subfamily B member 1 (GOLGB1) gene is not only a widely expressed large coiled-coil protein, but also a Golgi-associated large transmembrane protein [1]. To date, mutations in Golgi-associated proteins have been found to be associated with scores of human developmental disorders and diseases [2,3]. A previous study reported that the GOLGB1 loss-of-function mutation was co-segregated with cleft palate, and GOLGB1 mutant embryos showed intrinsic defects in palatal shelf elevation. These results suggest that GOLGB1 plays an important role in glycosylation and tissue morphogenesis of protein [4]. Another previous study reported that GOLGB1 gene is expressed in cultured chondrocytes, and various organs and embryos during different developmental stages [5]. It was also found that the coat protein 1 vesicle tethering factor encoded by the GOLGB1 gene plays a key role in many aspects of cartilage [6]. A 10-bp indel in exon 13 of the GOLGB1 gene in OCD rats is associated with spontaneous osteochondral dysplasia and systemic edema [6]. GOLGB1 rs3732410 was found to be significantly associated with a reduced risk of hemorrhagic stroke (HS) in people ≤ 50 years of age [7]. A genome-wide associated study has shown that one mutation in GOLGB1 (Y1212C) was significantly associated with a lower risk of stroke [8].

Many Chinese-local chickens show slow-growing and low-producing performance, which is not conductive to the development of the poultry industry, such as the Xinghua chickens, Qingyuan Partridge chickens, Lushi chickens, Gushi chickens, and Wenchang chickens in this study. The identification of thousands of indels in the last twenty years helped us to make progress in animal genetics and breeding. Mills et al. created the first indel map of the human genome, and an indel is a small genetic variation between 1 and 10,000 base pairs in length [9]. The number of indels in the genome is second only to that of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Through whole-genome sequencing of chickens, indels were found to play an important role in genetic diversity and phenotypic divergence [10,11]. During the whole-genome resequencing of domestic chicken leg feather traits, more than 2.1 million short indels were obtained [12]. Previous study has detected and identified about 883,000 high quality indels by whole-genome analysis of several modern layer chicken lines from diverse breeds [13]. Therefore, understanding indels in great detail is therefore important for profiling genetic variation within the genome, studying the evolution relationship of species, and detecting casual mutations of genetic disorders [13]. A large number of researches have elucidated the effects of indels’ polymorphism on livestock production in other gene structures [14]. For example, a 16-bp indel in KDM6A was significantly associated with growth traits in goat [15], and a 10-bp indel in PAX7 was associated with growth traits in cattle [16]. Many indels of functional genes in chicken were reported to associate with different chicken phenotypes. A 9-bp indel polymorphism in PMEL17 was associated with plumage color [17], a 24-bp indel in PRL was associated with egg production [18], a 8-bp indel in GHRL was associated with growth [19], a 31-bp indel in PAX7 was associated with performance [20], a multiallelic indel in the promoter region of CDKN3 gene was associated with body weight and carcass traits in chickens [21], a 80-bp indel in PRLR was associated with chicken growth and carcass traits [22], a 86-bp indel in MLNR was associated with chicken growth [23], two indels in the QPCTL gene were associated with body weight and carcass traits in chickens [24], and a 62-bp indel in TGFB2 was associated with body weight [25].

In our previous study identifying candidate genes underlying chickens’ yellow skin with resequencing data from Genbank, the GOLGB1 gene is found to be located on chromosome 1 and might be potentially associated with the yellow skin phenotype (data not published). As the candidate gene underlying yellow skin may also be associated with chicken growth, we screened the variations of the gene using the resequencing data from Chinese-local chicken breeds and Recessive White Rock chickens with various growing rates. As indicated above, this gene is well-studied in humans, but not in chickens. Furthermore, a total of 188 indels were identified in the GOLGB1 gene of chickens (https://ensembl.org/Gallus_gallus/Gene/Variation_Gene/Table?align=1760; db=core;g=ENSGALG00000041494; r=1:323123–357594). However, there is no report about the indel function of chickens on the GOLGB1 gene. Previous study has shown that a large number of quantitative trait locis (QTLs) on chicken chromosome 1 are related to the important economic traits such as growth [26]. However, the function of GOLGB1 on chicken growth is unclear. In this study, we detected a 65-bp indel in the fifth intron of GOLGB1 gene among Chinese-local chicken breeds. We further studied the relationship between the 65-bp indel in GOLGB1 and chicken growth traits, and further observed its expression patterns in different tissues. These results may provide a theoretical basis for further research on the application of molecular marker technology in the chicken industry.

2. Materials and Methods

All animal experiments in this study were conducted in accordance with the protocols approved by the South China Agriculture University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval number: SCAU#0015) and also in accordance with the Animal Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China.

2.1. Animal Samples and Genomic DNA Collection

In total, 1358 chicken samples, were composed of eight different Chinese-local chicken breeds, including Tianlu yellow chicken (N409, n = 382, 13 w of age), Mahuang chickens (MH, n = 578, 12 w of age), Wenchang chickens (WC, n = 88, 7 w of age), Guangxi Sanhuang chickens (SH, n = 72, 12 w of age), Gushi chickens (GS, n = 69, 16 w of age), Xinghua chickens (XH, n = 71, 17 w of age), Qingyuan Partridge chickens (QY, n = 60, 7 w of age), and Lushi chickens (LS, n = 38, 6 w of age). The N409 population was from Guangdong Wen’s Southern Poultry Breeding Co., Ltd. in Guangdong Province, China. A total of 18 traits were recorded, including carcass traits, body size traits, and fatness traits, and were used for statistical analysis [27].

DNA samples in this study were extracted from blood samples by using the NRBC Blood DNA Kit (OMEGA, BIO-TEK, Vernuski, VT, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. After using a Nanodrop2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to assay, all DNA samples were uniformly diluted to 80 ng/μL and stored at −20 °C.

In addition, 10 Xinghua chickens and 10 Recessive White Rock chickens were used for whole-genome sequencing using Hiseq 2500. The average sequencing coverage of the two lines was 10X. High-quality sequencing libraries were constructed by stringently following the standard protocol of IlluminaTruSeq™ DNA preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.2. Genetic Variation and Genotyping

In order to get more information about the polymorphism distribution of the 65-bp indel, we used PCR amplification and agarose gel electrophoresis to detect the genotypes in the eight different Chinese-local chicken breeds. According to the GOLGB1 gene sequence published on NCBI, the primer P1 (Table 1) was designed to amplify the DNA fragment including the 65-bp indel. A 10.0 μL reaction system was set up for each sample, containing 1.0 μL of template DNA, 0.3 μM per primer, 5.0 μL of 2 × Taq PCR StarMix (GenStar, Beijing, China), and 2.9 μL of ultrapure water. The PCR amplification procedure is as follows, pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 30 s, 34 cycles, and finally extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Next, PCR products were detected by 2.0% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the products of different genotypes were verified by sequencing (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China).

Table 1.

Primers for amplifying the chicken GOLGB1 gene.

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Product Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | F: TGTGGTAGCTCTCTCCTCCC | 311 |

| R: AGGCTCTCCTGCTGACCATA | ||

| P2 | F: CACTGCGAACCCACGAGA | 157 |

| R: CCCAAACCTGACAAACGGC | ||

| β-actin | F: GACTGACCGCGTTACTCCCA | 166 |

| R: CCAACCATCACACCCTGATGTC |

The genotype and allele frequencies of the eight breeds were calculated and the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was calculated by using the SHEsis program [28]. In addition, the populations indexes such as effective allele numbers (Ne), polymorphic information content (PIC), homozygosity (Ho), and heterozygosity (He) were calculated following Nei’s methods [29], which were performed by PopGene (version 1.3.1, Edmonton, AB, Canada).

2.3. RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

RNA was isolated from thirteen tissues including heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, duodenum, intestine, ovary, abdominal, breast muscle, leg muscle, hypothalamus, and cerebellum of 4 MH chickens (20 w of age). The RNA was then used as a tissue expression pattern analysis after reverse transcription into cDNA. Liver tissues from 12 indigenous XH chickens were used to compare the relative mRNA expression levels of different genotypes in the GOLGB1 gene. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the total RNA in each tissue was extracted using Trizol reagent (TaKaRa, Otsu, Japan). The integrity of all obtained RNA samples were determined by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the concentrations of all RNA samples were measured by a Nanodrop2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

The PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa, Otsu, Japan) was used for the complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis of mRNA according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

2.4. Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on an ABI Quantstudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (ABI, Los Angeles, CA, USA) using an iTaqTM Universal SYBR® Green Supermix Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Three repetitions for each sample were designed to make the result more accurate. Primer Premier5.0 software (Premier Bio-soft International, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used to design the qPCR primers, then sent to Tsingke Biotech Co. Ltd. (Guangzhou, China) for synthesis, and β-actin was used to internally reference genes. Primer information is shown in Table 1. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to calculate the relative mRNA expression of the GOLGB1 gene. After the data was normalized, significance was determined by ANOVA. Data were presented as the mean ± standard error.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The association analysis was performed on the genotypes and the traits of the N409 chickens using the General Linear Models Procedures of SAS 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A mix procedure was used to analyze its genetic effects. The specific GLM model is as follows,

| Yijkl = μ + Si + Gj + Hk + Fl + eijkl |

where Y represents the traits’ phenotypic values; μ represents the all population mean; S represents the fixed effect of sex; G represents the fixed effect of genotype or haplotype pair; H represents the fixed effect of hatch; F represents the fixed effect of family; e represents the random residuals. The p-value was calculated by the Student’s t-test [30]. All data are expressed as mean ± standard error, too.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of a Novel GOLGB1 65-bp Indel Polymorphism

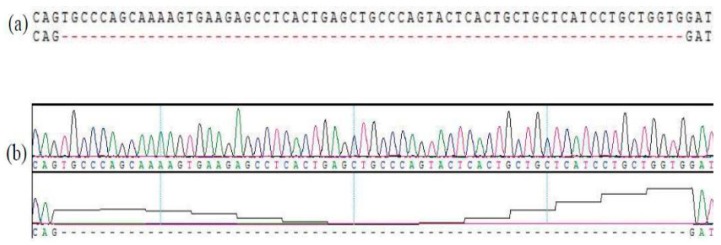

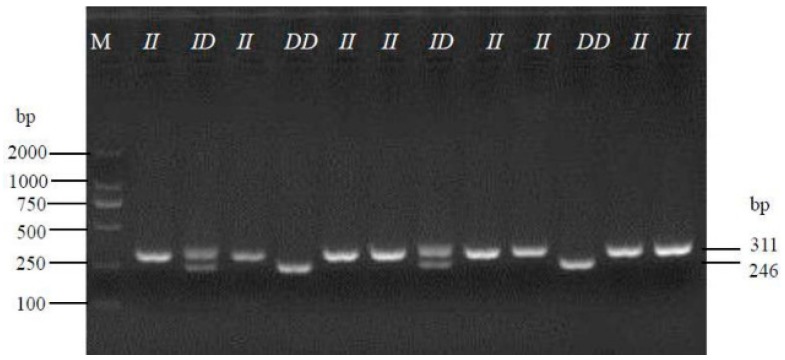

A novel 65-bp indel (NC_006088.5:g.332982instgcccagcaaaagtgaagagcctcactgagctgcccagtactcact gctgctcatcctgctggtg) was found in the fifth intron in the GOLGB1 gene (Gene ID: 426868, Figure 1). And this indel has been submitted in the EVA database (PROJECT:PRJEB37183). Three genotypes of II, ID, and DD were detected in eight different Chinese-local chicken breeds, in which allele “I” was 311 bp in length, while allele “D” was 246 bp in length (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

A 65-bp indel mutation in the fifth intron region of the GOLGB1 gene was identified. (a) Sequence diagram of the 65-bp indel variants. (b) Sequence peak diagram of the 65-bp indel variants.

Figure 2.

Electrophoresis pattern was performed to detect the 65-bp indel within the chicken GOLGB1 gene.

3.2. Genetic Diversity of the 65-bp Indel in the Eight Different Chinese Local Chickens

The genotypic frequencies, allele frequencies, and the diversity of the 65-bp indel in the eight different breeds were calculated and shown in Table 2. In all breeds, the frequencies of the allele “I” (0.51–0.77) were higher than those of the allele “D” (0.23–0.49). Of note, LS, as a game breed, showed the lowest frequency of allele “I”, and MH and N409, as improved local breeds, showed the highest frequencies of allele “I”. According to the result of the χ2 test, the distribution of genotypic and allele frequencies of the 65-bp indel was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in all populations (p > 0.05). The values of He and Ne were 0.341–0.500 and 1.517–1.999, respectively. According to the classification of PIC, all of the eight Chinese-local chicken breeds exhibited moderate polymorphism at the 65-bp indel polymorphism (0.250 < PIC < 0.500), which suggested that the eight Chinese-local chicken breeds may have experienced similarly persistent selection pressures in evolutionary history.

Table 2.

Genetic parameters of the GOLGB1 65-bp indel polymorphism in the eight chicken breeds.

| Breeds | Genotypic Distribution | Allelic Frequencies | He | Ne | PIC | HWE (p-Value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II | ID | DD | n | I | D | |||||

| WC | 49 | 30 | 9 | 88 | 0.73 | 0.27 | 0.397 | 1.658 | 0.318 | 0.124 |

| SH | 30 | 32 | 10 | 72 | 0.64 | 0.36 | 0.461 | 1.857 | 0.355 | 0.102 |

| GS | 37 | 27 | 5 | 74 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.392 | 1.646 | 0.315 | 0.125 |

| XH | 25 | 39 | 7 | 71 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 0.468 | 1.879 | 0.358 | 0.100 |

| QY | 26 | 27 | 7 | 60 | 0.66 | 0.34 | 0.450 | 1.818 | 0.349 | 0.998 |

| LS | 11 | 17 | 10 | 38 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.500 | 1.999 | 0.375 | 0.519 |

| MH | 335 | 211 | 32 | 578 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 0.363 | 1.569 | 0.297 | 0.871 |

| N409 | 229 | 138 | 14 | 381 | 0.77 | 0.23 | 0.341 | 1.517 | 0.283 | 0.220 |

WC, Wenchang chickens; SH, Shanhuang chickens; GS, Gushi chicken; XH, Xinghua chickens; QY, Qingyuanma chickens; LS, Lushi chickens; MH, Mahuang chickens; N409, Tianlu yellow chickens. Ne, effective allele numbers; He, gene heterozygosity; PIC, polymorphic information content; p-value (HWE), p-value of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

3.3. Association of the 65-bp Indel with Chicken Growth Traits

As can be seen from Table 3, the 65-bp indel of the GOLGB1 gene was significantly associated with body weight (p = 0.0121), neck weight (p = 0.0026), abdominal fat weight (p = 0.0006), abdominal fat percentage (p = 0.0015), and the yellow index b of breast (p = 0.0039) at 95 d of age in N409 chicken (n = 382). Notably, except for the yellow index b of breast, the II genotype is the dominant ones among the three genotypes.

Table 3.

Association analysis of the GOLGB1 65-bp indel with N409 chicken growth traits.

| Traits | (Mean ± SE) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| II | ID | DD | ||

| Body weight | 1735.16 ± 12.21a | 1705.38 ± 15.56a | 1594.71 ± 49.077b | 0.0121 |

| Neck weight | 117.17 ± 1.19a | 111.80 ± 1.53b | 104.86 ± 4.82b | 0.0026 |

| Abdominal fat weight | 102.35 ± 1.91a | 93.65 ± 2.46b | 77.83 ± 7.74b | 0.0006 |

| Abdominal fat percentage | 5.83 ± 0.089a | 5.42 ± 0.11b | 4.85 ± 0.36b | 0.0015 |

| Yellow index b of breast | 3.78 ± 0.26a | 3.71 ± 0.33a | 7.36 ± 1.05b | 0.0039 |

| Eviscerated weight | 1050.03 ± 7.96 | 1036.66 ± 10.22 | 998.77 ± 32.20 | 0.2188 |

| Subcutaneous fat thickness | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 0.76 ± 0.14 | 0.67 ± 0.44 | 0.1627 |

| Chest width | 7.09 ± 0.27 | 7.10 ± 0.35 | 7.12 ± 1.09 | 0.9565 |

| Back width | 8.62 ± 0.39 | 8.57 ± 0.50 | 8.40 ± 1.56 | 0.3255 |

| Body length | 43.07 ± 0.10 | 42.87 ± 0.13 | 42.71 ± 0.42 | 0.4130 |

| Shank length | 7.76 ± 0.23 | 7.80 ± 0.30 | 7.78 ± 0.94 | 0.6231 |

| Cockscomb height | 2.49 ± 0.35 | 2.38 ± 0.45 | 2.46 ± 1.41 | 0.1935 |

| Yellow index L of abdominal fat | 42.20 ± 0.30 | 43.03 ± 0.39 | 41.75 ± 1.23 | 0.2078 |

| Yellow index L of breast | 57.78 ± 0.36 | 56.92 ± 0.46 | 56.37 ± 1.46 | 0.2671 |

| Yellow index a of breast | 2.73 ± 0.08 | 2.60 ± 0.11 | 2.89 ± 0.34 | 0.5423 |

| Yellow index L of leg | 62.70 ± 0.24 | 62.53 ± 0.31 | 62.20 ± 0.98 | 0.4124 |

| Yellow index a of leg | 13.72 ± 0.19 | 13.64 ± 0.24 | 14.46 ± 0.76 | 0.5917 |

| Yellow index b of leg | 35.22 ± 0.31 | 34.84 ± 0.39 | 36.51 ± 1.23 | 0.3870 |

Different letters in the same row indicate a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05).

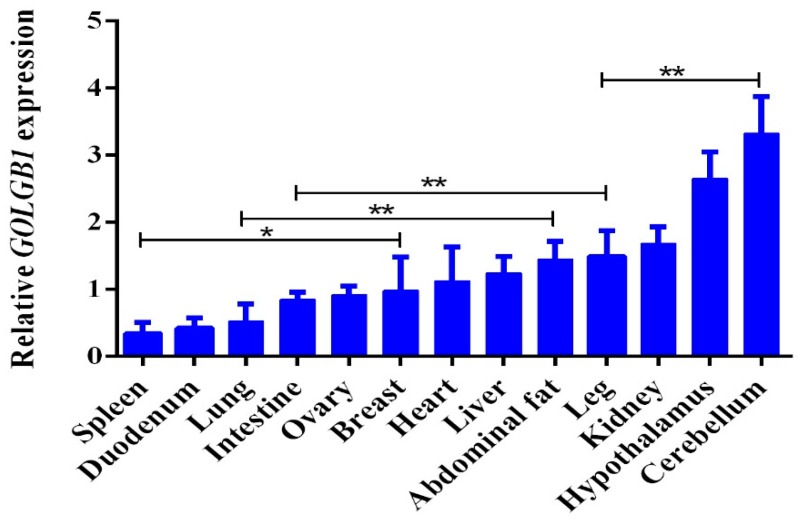

3.4. The Expression Profiles of the Chicken GOLGB1 Gene

The mRNA expression levels of GOLGB1 gene in 13 tissues of MH chicken were detected by qRT-PCR. The GOLGB1 gene is expressed in all tissues. Additionally, GOLGB1 was highly expressed in the cerebellum, hypothalamus, kidney, and abdominal fat (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Relative mRNA expression levels of the GOLGB1 gene in different tissues; the relative mRNA expression levels of GOLGB1 were normalized to that of β-actin. *: represent a significant difference (p < 0.05); **: represent a very significant difference (p < 0.01).

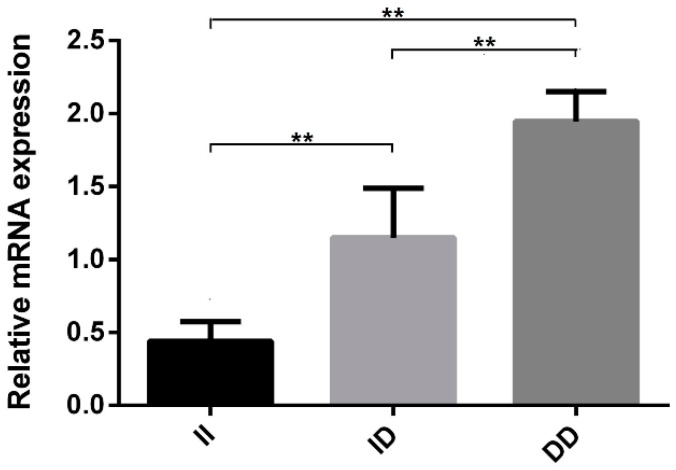

3.5. Significantly Differential Gene Expression of the Three Genotypes

Statistical analysis showed that the 65-bp indel of the GOLGB1 gene was significantly associated with growth and carcass traits, and analysis of the expression profiles showed that GOLGB1 gene was widely expressed in the tissues of chickens. Next, we examined the expression of liver tissues in different genotypes of the GOLGB1 gene, and found that the relative mRNA expression level of DD genotype was the highest. Moreover, the mRNA expression level of the DD genotype was significantly higher than in the II and ID genotypes (p < 0.01, Figure 4). These results suggested that the different genotypes might have different effects on chickens.

Figure 4.

Expression levels of the GOLGB1 gene in the livers of chickens with different genotypes. Data represent means ± SE; **: represent a very significant difference (p < 0.01).

4. Discussion

Body weight, as one of the most important economic traits in the broiler-breeding industry, has been closely selected for many years [31]. As indicated above, a large number of indels associated with body weight have been reported in chickens. In this study, we first discovered a novel 65-bp indel polymorphism in the fifth intron of the GOLGB1 gene and verified it in eight different Chinese-local breeds, and we further studied the genetic diversity and characterized the genetic properties. Finally, it was found that the 65-bp indel was significantly associated with body weight, abdominal fat weight, and abdominal fat percentage. Additionally, we found that the frequencies of the allele “I” was higher than those of the allele “D” in all breeds. And chickens with II genotype had significantly better body weight than those with ID and DD genotypes. Besides, we also found an interesting phenomenon that the yellow index b of breast is higher in the DD genotype, which is opposite to the body weight and abdominal fat weight. The relationship between abdominal fat weight and skin color needs further study.

GOLGB1 belongs to the golgin family of large coiled-coil proteins located at the cytoplasmic surface of the Golgi apparatus [32]. GOLGB1 is unique, because among all Golgi proteins, it contains not only a transmembrane domain that can anchor the protein on Golgi membrane or COP1 vesicle at the C-terminal, but also a p115 binding domain at the N-terminal [33,34,35,36]. The function of the GOLGB1 gene in chicken has not been studied. In this study, we found that the 65-bp indel of intron 5 of the GOLGB1 gene was significant associated with body weight, neck weight, abdominal fat weight, abdominal fat percentage, and the yellow index b of breast in N409 chicken. In addition, “I” was the predominant allele in all populations. Except for the yellow index b of breast trait, the II genotype was the dominant genotype in the other traits. These results indicate that the 65-bp indel may be a potential molecular marker of chicken growth and carcass traits.

Introns, non-coding spacer sequences that interrupt the linear expression of genes, are removed during the processing of the original transcription product and are not included in the sequence of mature mRNA. Introns play an important role in the regulation of gene expression [37], and a previous study has shown that removal of introns from a transgene or insertion of a transgene results in increased expression [38]. Some introns have an enhancer function [39], or contain enhancer elements that co-regulated genes with promoters [40]. In addition, SNPs on introns often alter mRNA levels by affecting transcription, RNA elongation, splicing, or maturation [41]. Cui and his colleagues identified a 16-bp indel in KDM6A intron 17, and found that the indel significantly affected KDM6A gene expression [42]. The 31-bp indel in PAX7 intron 3 was associated with growth, carcass, and meat-quality traits of chickens [20]. However, further research is needed on its functional impact on gene expression. In this study, we found that the GOLGB1 gene was expressed in different tissues, which is consistent with previous reports that the GOLGB1 gene was widely expressed [1]. Additionally, the GOLGB1 gene was highly expressed in cerebellum, hypothalamus, kidney, liver, and abdominal fat, suggesting that it might be related to growth and fat deposition. Notably, the GOLGB1 gene with the DD genotype showed higher expression than the II and ID genotypes in the liver tissue of chickens. The body weight, neck weight, abdominal fat weight, and abdominal fat percentage of individuals with the DD genotype are lower than those with the genotype II. Therefore, we argued that the 65-bp indel had a positive effect on chicken’s body weight, neck weight, abdominal fat weight, and abdominal fat percentage.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we identified a 65-bp indel in the fifth intron region of the GOLGB1 gene. The 65-bp indel of the GOLGB1 gene was associated with chicken body weight, neck weight, abdominal fat weight, abdominal fat percentage, and the yellow index b of breast. The above results will provide useful information for GOLGB1 as a molecular marker for chicken-breeding programs, and enrich the understanding of the GOLGB1 gene function.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zhenhui Li for editing the language of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F.; T.R. and X.Z.; Data curation, R.F.; T.R., W.L. (Wangyu Li), J.L., G.M., W.L. (Wen Luo) and D.H.; Formal analysis, R.F. and T.R.; Funding acquisition, X.Z.; Investigation, W.L. (Wen Luo) and S.L.; Methodology, R.F., W.L. (Wangyu Li), J.L. and G.M.; Project administration, X.Z.; Resources, D.H., S.L., X.Z.; Software, R.F. and T.R.; Supervision, D.H. and S.L.; Writing—original draft, R.F.; Writing—review & editing, R.F. and X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the China Agriculture Research System (Grant No. CARS-41-G03), and the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (Grant No. 201804020088).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Linstedt A.D., Hauri H.P. Giantin, a novel conserved Golgi membrane protein containing a cytoplasmic domain of at least 350 kDa. Mol. Boil. Cell. 1993;4:679–693. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.7.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smits P., Bolton A.D., Funari V., Hong M., Boyden E.D., Lu L., Manning D.K., Dwyer N.D., Moran J., Prysak M., et al. Lethal skeletal dysplasia in mice and humans lacking the golgin GMAP-210. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:206–216. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeze H.H., Ng B.G. Golgi Glycosylation and Human Inherited Diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Boil. 2011;3:a005371. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lan Y., Zhang N., Liu H., Xu J., Jiang R. Golgb1 regulates protein glycosylation and is crucial for mammalian palate development. Development. 2016;143:2344–2355. doi: 10.1242/dev.134577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansen J.S., Olee T., Price P.A., Hashimoto S., Ochs R.L., Lotz M. Regulation of YKL-40 production by human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:826–837. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<826::AID-ANR139>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kentaro K., Tetsu S., Syo G., Kei O., Hiromi M., Katsushi S., Hiroetsu S. Insertional mutation in the Golgb1 gene is associated with osteochondrodysplasia and systemic edema in the OCD rat. Bone. 2011;49:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu W., Ge S., Liu Y., Wei C., Ding Y., Chen A., Wu Q., Zhang Y. Polymorphisms in three genes are associated with hemorrhagic stroke. Brain Behav. 2015;5:00395. doi: 10.1002/brb3.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flanagan J.M., Sheehan V., Linder H., Howard T.A., Wang Y.-D., Hoppe C.C., Aygun B., Adams R.J., Neale G.A., Ware R.E. Genetic mapping and exome sequencing identify 2 mutations associated with stroke protection in pediatric patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2013;121:3237–3245. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-464156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mills R.E., Luttig C.T., Larkins C.E., Beauchamp A., Tsui C., Pittard W.S., Devine S.E. An initial map of insertion and deletion (INDEL) variation in the human genome. Genome Res. 2006;16:1182–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.4565806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao Y.S., Wang Z.F., Chai X.W., Wu G.Z., Nie Q.H., Zhang X.Q. Indel segregating within introns in the chicken genome are positively correlated with the recombination rates. Hereditas. 2010;147:53–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.2009.2141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan Y., Yi G., Sun C., Qu L., Yang N. Genome-Wide Characterization of Insertion and Deletion Variation in Chicken Using Next Generation Sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e104652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang S., Shi Z., Ou X., Liu G. Whole-genome resequencing reveals genetic indels of feathered-leg traits in domestic chickens. J. Genet. 2019;98:47. doi: 10.1007/s12041-019-1083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boschiero C., Gheyas A.A., Ralph H., Eory L., Paton I.R., Kuo R.I., Fulton J.E., Preisinger R., Kaiser P., Burt D. Detection and characterization of small insertion and deletion genetic variants in modern layer chicken genomes. BMC Genom. 2015;16:562. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1711-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X., Li Z., Guo Y., Wang Y., Sun G., Jiang R., Kang X., Han R.-L. Identification of a novel 43-bp insertion in the heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase 3 (HS6ST3) gene and its associations with growth and carcass traits in chickens. Anim. Biotechnol. 2018;30:1–8. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2018.1479712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang K., Cui Y., Wang Z., Yan H., Meng Z., Zhu H., Qu L., Lan X., Pan C. One 16-bp insertion/deletion (indel) within the KDM6A gene revealing strong associations with growth traits in goat. Gene. 2019;686:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Y., Shi T., Zhou Y., Liu M., Klaus S., Lan X., Lei C., Chen H. A novel PAX7 10-bp indel variant modulates promoter activity, gene expression and contributes to different phenotypes of Chinese cattle. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1724. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20177-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerje S., Sharma P., Gunnarsson U., Kim H., Bagchi S., Fredriksson R., Schütz K., Jensen P., Von Heijne G., Okimoto R., et al. The Dominant white, Dun and Smoky Color Variants in Chicken Are Associated With Insertion/Deletion Polymorphisms in the PMEL17 Gene. Genetics. 2004;168:1507–1518. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui J.-X., Du H.-L., Liang Y., Deng X.-M., Li N., Zhang X. Association of Polymorphisms in the Promoter Region of Chicken Prolactin with Egg Production. Poult. Sci. 2006;85:26–31. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang M., Nie Q., Luo C., Zhang D., Zhang X. An 8bp indel in exon 1 of Ghrelin gene associated with chicken growth. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2007;32:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang S., Han R., Gao Z., Zhu S., Tian Y., Sun G., Kang X. A novel 31-bp indel in the paired box 7 (PAX7) gene is associated with chicken performance traits. Br. Poult. Sci. 2014;55:31–36. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2013.860215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W., Liu D., Tang S., Li D., Han R.-L., Tian Y.-D., Li H., Li G., Li W., Liu X., et al. A multiallelic indel in the promoter region of the Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 gene is significantly associated with body weight and carcass traits in chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:556–565. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang K., Wang X., Tian X., Geng R., Li W., Jing Z., Han R., Tian Y., Liu X., Kang X., et al. Molecular characterization and an 80-bp indel polymorphism within the prolactin receptor (PRLR) gene and its associations with chicken growth and carcass traits. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:296. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1827-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu D., Han R., Wang X., Li W., Tang S., Wang Y., Jiang R., Yan F., Wang C., Liu X., et al. A novel 86-bp indel of the motilin receptor gene is significantly associated with growth and carcass traits in Gushi-Anka F2 reciprocal cross chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2019;60:649–658. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2019.1655710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren T., Li W., Liu D., Liang K., Wang X., Li H., Jiang R., Tian Y., Kang X., Li Z. Two insertion/deletion variants in the promoter region of the QPCTL gene are significantly associated with body weight and carcass traits in chickens. Anim. Genet. 2019;50:279–282. doi: 10.1111/age.12741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang S., Ou J., Sun D., Xu G., Zhang Y. A novel 62-bp indel mutation in the promoter region of transforming growth factor-beta 2 (TGFB2) gene is associated with body weight in chickens. Anim. Genet. 2011;42:108–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2010.02060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie L., Luo C., Zhang C., Zhang R., Tang J., Nie Q., Ma L., Hu X., Li N., Da Y., et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identified a Narrow Chromosome 1 Region Associated with Chicken Growth Traits. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang Q.Q. Master’s Thesis. South China Agricultural University; Guangzhou, China: 2018. Study on the Selection Method of High Quality Chicken Belly Fat Rate. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yong Y., He L. SHEsis, a powerful software platform for analyses of linkage disequilibrium, haplotype construction, and genetic association at polymorphism loci. Cell Res. 2005;15:97–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nei M., Roychoudhury A.K. Sampling Variances of Heterozygosity and Genetic Distance. Genetics. 1974;76:379–390. doi: 10.1093/genetics/76.2.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X., Ouyang H., Chen B., Li G., Wang Z., Nie Q. Genetic effects of the EIF5A2 gene on chicken growth and skeletal muscle development. Livest. Sci. 2019;225:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2019.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X., Zhang H., Li H., Li N., Zhang Y., Zhang Q., Wang S., Wang Q., Wang H. Fine-Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci for Body Weight and Abdominal Fat Traits: Effects of Marker Density and Sample Size. Poult. Sci. 2008;87:1314–1319. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munro S. The Golgin Coiled-Coil Proteins of the Golgi Apparatus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Boil. 2011;3:a005256. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sapperstein S.K., Walter D.M., Grosvenor A.R., Heuser J.E., Waters M.G. p115 is a general vesicular transport factor related to the yeast endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport factor Uso1p. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:522–526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez C., Garcia-Mata R., Hauri H.-P., Sztul E. The p115-interactive Proteins GM130 and Giantin Participate in Endoplasmic Reticulum-Golgi Traffic. J. Boil. Chem. 2000;276:2693–2700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007957200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puthenveedu M., Linstedt A.D. Evidence that Golgi structure depends on a p115 activity that is independent of the vesicle tether components giantin and GM130. J. Cell Boil. 2001;155:227–238. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sönnichsen B., Lowe M., Levine T., Jämsä E., Dirac-Svejstrup B., Warren G. A Role for Giantin in Docking COPI Vesicles to Golgi Membranes. J. Cell Boil. 1998;140:1013–1021. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaul O. How introns enhance gene expression. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Boil. 2017;91:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chatterjee S., Min L., Karuturi R.K.M., Lufkin T. The role of post-transcriptional RNA processing and plasmid vector sequences on transient transgene expression in zebrafish. Transgenic Res. 2009;19:299–304. doi: 10.1007/s11248-009-9312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan Y.-Y., Chen R., Zhu L., Wang H., Huang D.-F., Lang Z.-H. Utilizing modified ubi1 introns to enhance exogenous gene expression in maize (Zea mays L.) and rice (Oryza sativa L.) J. Integr. Agric. 2016;15:1716–1726. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(15)61260-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torre C.M.D.L., Finer J.J. The intron and 5′ distal region of the soybean Gmubi promoter contribute to very high levels of gene expression in transiently and stably transformed tissues. Plant. Cell Rep. 2015;34:111–120. doi: 10.1007/s00299-014-1691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang D., Guo Y., Wrighton S.A., Cooke G.E., Sadee W. Intronic polymorphism in CYP3A4 affects hepatic expression and response to statin drugs. Pharmacogenomics J. 2010;11:274–286. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2010.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cui Y., Yan H., Wang K., Xu H., Zhang X., Zhu H., Liu J., Qü L., Lan X., Pan C. Insertion/Deletion Within the KDM6A Gene Is Significantly Associated With Litter Size in Goat. Front. Genet. 2018;9:91. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]