Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a severe public health problem globally. Both epidemiological and laboratory studies have shown that ambient temperature could affect the transmission and survival of coronaviruses. This study aimed to determine whether the temperature is an essential factor in the infection caused by this novel coronavirus.

Methods

Daily confirmed cases and meteorological factors in 122 cities were collected between January 23, 2020, to February 29, 2020. A generalized additive model (GAM) was applied to explore the nonlinear relationship between mean temperature and COVID-19 confirmed cases. We also used a piecewise linear regression to determine the relationship in detail.

Results

The exposure-response curves suggested that the relationship between mean temperature and COVID-19 confirmed cases was approximately linear in the range of <3 °C and became flat above 3 °C. When mean temperature (lag0–14) was below 3 °C, each 1 °C rise was associated with a 4.861% (95% CI: 3.209–6.513) increase in the daily number of COVID-19 confirmed cases. These findings were robust in our sensitivity analyses.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that mean temperature has a positive linear relationship with the number of COVID-19 cases with a threshold of 3 °C. There is no evidence supporting that case counts of COVID-19 could decline when the weather becomes warmer, which provides useful implications for policymakers and the public.

Keywords: Temperature, Novel coronavirus pneumonia, COVID-19, China, Generalized additive model

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Mean temperature of last two weeks (when < 3 °C) was positively associated with newly confirmed COVID-19 cases.

-

•

1 °C rise in the mean temperature of last weeks (when < 3 °C) was associated with a 4.861% increase in the daily confirmed cases.

-

•

There is no evidence supporting that case counts of COVID-19 could decline when the weather becomes warmer.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the novel coronavirus, was first discovered in Wuhan city, China (Chen et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2020). Subsequently, it spread rapidly to other provinces, although the government has taken timely measures to shut down the traffic (Du et al., 2020; Kupferschmidt and Cohen, 2020). As of 29 February 2020, data from the National Health Commission have shown that >79,000 confirmed cases have been identified and over 2800 deaths in the whole of China. Besides China, other countries and regions are also affected by COVID-19, which has become a serious public health problem globally (Sohrabi et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020).

COVID-19 infection could cause severe respiratory illness, similar to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) (Huang et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). Generally, fever, cough, and myalgia or fatigue are common symptoms at the onset of illness (Huang et al., 2020). Early studies have demonstrated person-to-person transmission of COVID-19 through direct contact or droplets (Chan et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Specifically, a study reported that presumed person-to-person hospital-associated transmission of COVID-19 was suspected in 41% of patients (Wang et al., 2020).

In addition to human-to-human contact, both epidemiological and laboratory studies have shown that ambient temperature is an important factor in the transmission and survival of coronaviruses (Bi et al., 2007; Casanova et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2011; Tan et al., 2005; Van Doremalen et al., 2013). For example, temperature could increase or decrease the transmission risk by affecting the survival time of coronaviruses on surfaces (Casanova et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2011; Van Doremalen et al., 2013). Therefore, it is reasonable to explore the effect of temperature on the spread of this novel coronavirus. To provide useful implications for policymakers and the public, our paper aimed to investigate the relationship between daily mean temperature and newly confirmed COVID-19 cases in 122 cities from China.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

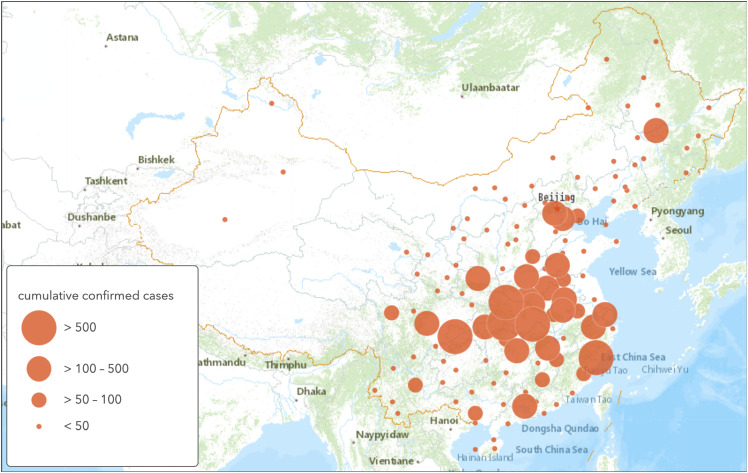

Our study included 118 prefecture-level cities and 4 municipalities that covered the majority of the Chinese mainland (19.1° to 51.4° north latitude and 83.4° to 131.6° east longitude). Fig. 1 shows the locations of these 122 cities and the cumulative confirmed cases in each city as of February 29, 2020. We focused on these cities since the meteorological data we have obtained was limited (not including all cities in China).

Fig. 1.

Locations of 122 cities and cumulative confirmed cases in each city as of February 29, 2020.

2.2. Data collection

Daily confirmed cases were collected from the official websites of health commissions in corresponding provinces or cities between January 23, 2020 (i.e., the lockdown of Wuhan) to February 29, 2020. We obtained the data after the closure of Wuhan to minimize the potential inclusion of imported cases in this study.

Meteorological data during the same study period for each city were collected from National Meteorological Information Center (http://data.cma.cn). Meteorological factors included daily mean temperature, relative humidity, air pressure, and wind speed.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The generalized additive model (GAM) is a semi-parametric extension of the generalized linear model (GLM), which is useful to explore the nonlinear relationship between weather factors and health outcomes (Lin et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2006; Talmoudi et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2018). Because the temperature effect could last for several days and the incubation period of COVID-19 ranges from 1 day to 14 days (reported by National Health Commission in China), it is a reasonable choice to use a moving-average approach to account for the cumulative lag effect of temperature (Duan et al., 2019; Li et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2015). Therefore, in this study, a GAM with a Gaussian distribution family (Hastie, 2017; Liu et al., 2020) was applied to examine the moving average lag effect (lag0–7, lag0–14, lag0–21) of mean temperature on daily confirmed cases of COVID-19. The model was defined as follows:

In the model, log(y it) is the log-transformed newly COVID-19 counts in city i on day t (added one to avoid taking the logarithm of zeros) (Liu et al., 2020). a is the intercept and s(∙) denotes a thin plate spline function with the maximum 2 degrees of freedom to avoid overfitting (Liu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2018). meantem il is the (l + 1)-day moving average term (lag0-l) of daily mean temperature in city i. We also controlled the relative humidity (rhu il), air pressure (prs il), and wind speed (win il) during the same period for the possible confounding effect. log(y i , t−1) is the log-transformed COVID-19 counts lagged one day in city i to account for potential serial correlation in the data (Hunter et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020). city i is the city fixed effect variable and day t captures day fixed effect (Amuakwa-Mensah et al., 2017).

According to the results from the GAMs, then we used a piecewise linear regression to determine the relationship between mean temperature and COVID-19 confirmed cases in detail (Cheng et al., 2019; Dukić et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2016; Qian et al., 2008). In the sensitivity analysis, we first excluded Wuhan city from our data because it was the worst-hit region in China and the number of confirmed cases was much larger than that of other cities. Second, we changed the maximum degree of freedom for the spline function to 3 to examine whether our main results were robust.

GAMs in our analysis were implemented via the “mgcv” package (version 1.8–28) of R software (version 3.5.2). The statistical tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analysis

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics for COVID-19 confirmed cases and meteorological variables. This study included >58,000 cases during the observation period (January 23, 2020 to February 29, 2020) and the average number was 12.726. Average daily mean temperature, relative humidity, air pressure, and wind speed were 3.118 °C, 67.48%, 964.931 hPa, and 2.116 m/s, respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of newly confirmed cases and meteorological variables across all cities and days.

| Mean (SD) | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily confirmed cases | 12.726 (227.082) | 0 | 13,436 |

| Mean temperature (°C) | 3.118 (10.286) | −33.8 | 26.9 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 67.480 (17.386) | 17 | 100 |

| Air pressure (hPa) | 964.931 (75.816) | 668.1 | 1039 |

| Wind speed (m/s) | 2.116 (1.199) | 0 | 15.4 |

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients among the meteorological variables. Mean temperature had significantly positive correlations with relative humidity (r = 0.354, p < 0.05) and air pressure (r = 0.163, p < 0.05). However, mean temperature was negatively correlated with wind speed (r = −0.053, p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Spearman correlation coefficients between meteorological variables across all cities and days.

| Mean temperature | Relative humidity | Air pressure | Wind speed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean temperature | 1.000 | |||

| Relative humidity | 0.354⁎ | 1.000 | ||

| Air pressure | 0.163⁎ | 0.274⁎ | 1.000 | |

| Wind speed | −0.053⁎ | −0.117⁎ | 0.127⁎ | 1.000 |

p < 0.05.

3.2. Relationship between temperature and COVID-19 confirmed cases

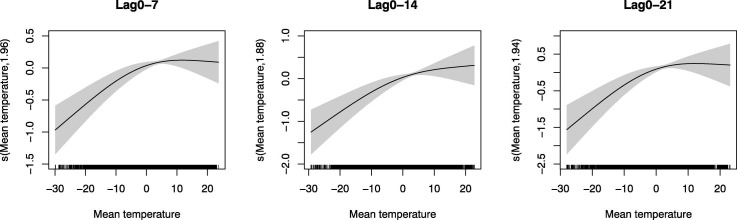

The exposure-response curves in Fig. 2 suggested that the relationship between temperature and COVID-19 confirmed cases was significantly nonlinear (lag0–7: p < 0.001, lag0–14: p < 0.001, lag0–21: p < 0.001). Specifically, the relationship was approximately linear in the range of <3 °C and became flat above 3 °C, indicating that the single threshold of the temperature effect on COVID-19 was 3 °C.

Fig. 2.

Exposure-response curves for the effects of temperature on COVID-19 confirmed cases. The x axis is the mean temperature (7-day, 14-day and 21-day moving average). The y axis indicates the contribution of the smoother to the fitted values.

Based on results from GAMs, a piecewise linear regression was adapted with a threshold at a 3 °C to quantify the effect of temperature above and below the threshold. As showed in Table 3 , each 1 °C rise in mean temperature (lag0–7) led to a 3.432% (95% CI: 2.277–4.586) increase in the daily number of COVID-19 confirmed cases when mean temperature was below 3 °C. This positive effect is largest at lag0–21 (percentage change = 6.953%, 95% CI: 4.681–9.225). When mean temperature was above 3 °C, the negative effect of temperature was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

The effects of a 1 °C increase in mean temperature on COVID-19 confirmed cases.

| Mean temperature ≤3 °C |

Mean temperature >3 °C |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage change (%) | 95% CI | Percentage change (%) | 95% CI | |

| Lag0–7 | 3.432⁎ | (2.277–4.586) | −0.895 | (−2.493–0.703) |

| Lag0–14 | 4.861⁎ | (3.209–6.513) | −0.750 | (−3.022–1.522) |

| Lag0–21 | 6.953⁎ | (4.681–9.225) | −1.858 | (−4.502–0.786) |

p < 0.05.

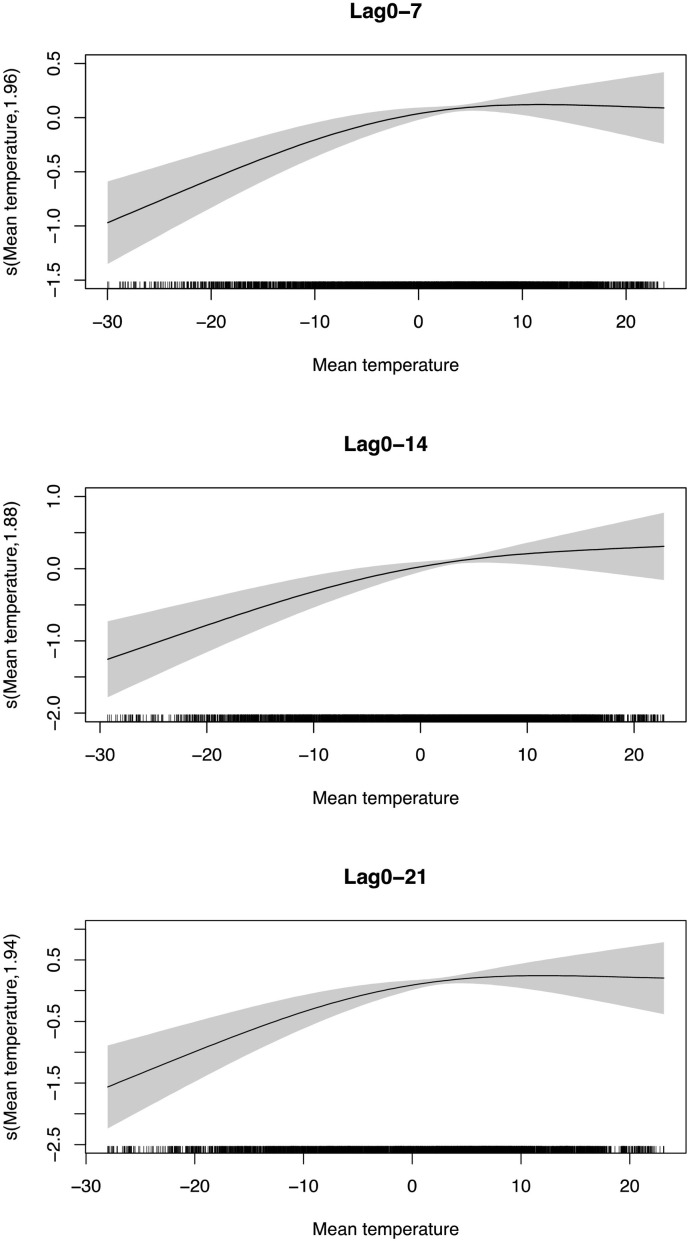

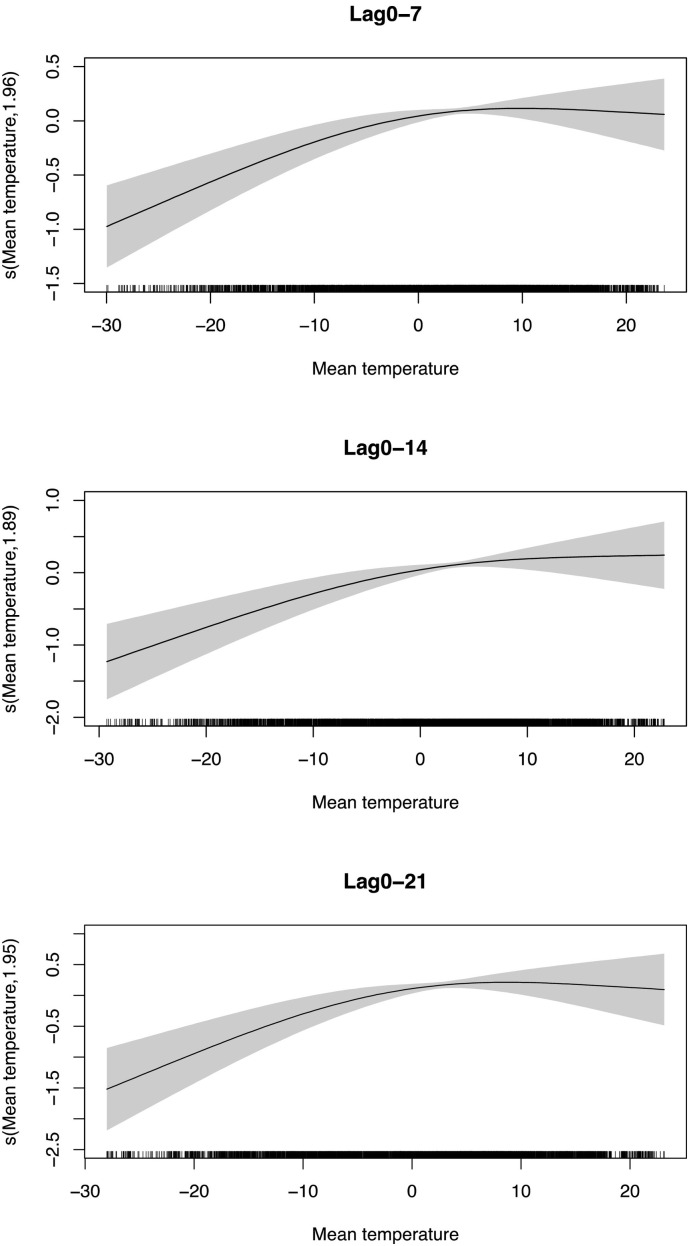

3.3. Sensitivity analysis

The nonlinear relationship was robust after excluding Wuhan city from our data (Fig. 3 ). We also used a piecewise linear model to quantify the effect in this sensitivity analysis (Table 4 ). Below the threshold 3 °C, the confirmed cases increased by 6.949% (95% CI: 4.692–9.205) for every 1 °C rise in mean temperature (lag0–21). Our main finding was robust when we changed the maximum degree of freedom for the spline function to 3 (Figs. S1–S2)

Fig. 3.

Exposure-response curves for the effects of temperature on COVID-19 confirmed cases after excluding Wuhan. The x axis is the mean temperature (7-day, 14-day and 21-day moving average). The y axis indicates the contribution of the smoother to the fitted values.

Table 4.

The effects of a 1 °C increase in mean temperature on COVID-19 confirmed cases after excluding Wuhan.

| Mean temperature ≤3 °C |

Mean temperature >3 °C |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage change (%) | 95% CI | Percentage change (%) | 95% CI | |

| Lag0–7 | 3.471⁎ | (2.322–4.619) | −1.151 | (−2.747–0.446) |

| Lag0–14 | 4.845⁎ | (3.204–4.486) | −1.305 | (−2.572–0.961) |

| Lag0–21 | 6.949⁎ | (4.692–9.205) | −2.606 | (−5.245–0.032) |

p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we explored the nonlinear relationship between ambient temperature and COVID-19 confirmed cases by using a generalized additive model. The exposure-response relationship was positive linear when the mean temperature below 3 °C and became flat above 3 °C, indicating that higher temperature may not limit the transmission of this novel coronavirus.

Previous studies have showed that temperature is also an important factor in the survival and transmission of other coronaviruses, like SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV (Bi et al., 2007; Casanova et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2011; Tan et al., 2005; Van Doremalen et al., 2013), so we compared our main findings with results in these studies. Tan et al. (2005) found that the optimum environmental temperature related to SARS cases was from 16 °C to 28 °C based on data from Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Beijing, and Taiyuan. Moreover, Bi et al. (2007) reported that temperature had a negative relationship with SARS transmission in Hong Kong and Beijing in 2003. A laboratory study using surrogate viruses to investigate the effect of temperature on coronavirus survival on surfaces showed that viruses were inactivated more rapidly at 20 °C than at 4 °C (Casanova et al., 2010). Another laboratory study found that coronavirus on smooth surfaces was stable for over 5 days when temperature at 22 °C–25 °C, and virus viability was rapidly lost at higher temperatures (e.g., 38 °C) (Chan et al., 2011). Van Doremalen et al. (2013) also observed that MERS-CoV was less stable at high temperature. In brief, most studies showed that there was an optimum temperature for coronavirus and high temperature was harmful to its viability. However, this paper could not observe a negative effect of high temperature on COVID-19 infection. A possible reason may be that the study period was limited in winter, with maximal mean temperature 26.9 °C. Further laboratory studies also need to be conducted to determine the underlying mechanism.

Our study has some implications. First, the nonlinear relationship between ambient temperature and COVID-19 confirmed cases showed COVID-19 may not perish of itself without any public health interventions when the weather becomes warmer. So, the public and governments could not expect the high temperature to eradicate this novel virus. Additionally, increasing temperature in regions or periods below 3 °C is related to the high risk of transmission, which provides useful information for policymakers if the novel coronavirus coexists with human for a long time.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, we could not conduct subgroup analysis by gender and age group to explore the sensitive population because there was a lack of patient information. Second, although the government has established a good disease surveillance system, under-reporting may still occur and could affect our main findings, especially at the beginning of COVID-19 outbreak. Third, our data only covered cities in China. Further studies on the effects of temperature on COVID-19 transmission in other countries are needed.

5. Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the nonlinear relationship between ambient temperature and daily COVID-19 confirmed cases. Our results indicate that mean temperature has a positive linear relationship with the number of COVID-19 cases when the temperature is below 3 °C. There is no evidence supporting that case counts of COVID-19 could decline when the weather becomes warmer, which provides useful implications for policymakers and the public.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The study was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant 71571176].

Editor: Jay Gan

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138201.

Contributor Information

Jingui Xie, Email: xiej@ustc.edu.cn.

Yongjian Zhu, Email: ustczyj@mail.ustc.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Changing the maximum degree of freedom to 3 for the spline function.

References

- Amuakwa-Mensah F., Marbuah G., Mubanga M. Climate variability and infectious diseases nexus: evidence from Sweden. Infectious Disease Modelling. 2017;2:203–217. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi P., Wang J., Hiller J. Weather: driving force behind the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome in China? Intern. Med. J. 2007;37:550–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova L.M., Jeon S., Rutala W.A., Weber D.J., Sobsey M.D. Effects of air temperature and relative humidity on coronavirus survival on surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:2712–2717. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02291-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K., Peiris J., Lam S., Poon L., Yuen K., Seto W. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. Adv. Virol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/734690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F.-W., Yuan S., Kok K.-H., To K.K.-W., Chu H., Yang J., Xing F., Liu J., Yip C.C.-Y., Poon R.W.-S. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Guo J., Wang C., Luo F., Yu X., Zhang W., Li J., Zhao D., Xu D., Gong Q. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;395:809–815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J., Xu Z., Bambrick H., Su H., Tong S., Hu W. Impacts of heat, cold, and temperature variability on mortality in Australia, 2000–2009. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;651:2558–2565. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z., Wang L., Cauchemez S., Xu X., Wang X., Cowling B., Meyers L. Risk for transportation of 2019 novel coronavirus disease from Wuhan to other cities in China. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2020;26 doi: 10.3201/eid2605.200146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y., Liao Y., Li H., Yan S., Zhao Z., Yu S., Fu Y., Wang Z., Yin P., Cheng J. Effect of changes in season and temperature on cardiovascular mortality associated with nitrogen dioxide air pollution in Shenzhen, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;697 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukić V., Hayden M., Forgor A.A., Hopson T., Akweongo P., Hodgson A., Monaghan A., Wiedinmyer C., Yoksas T., Thomson M.C. The role of weather in meningitis outbreaks in Navrongo, Ghana: a generalized additive modeling approach. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 2012;17:442–460. doi: 10.1007/s13253-012-0095-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T.J. Statistical Models in S. Routledge; 2017. Generalized additive models; pp. 249–307. [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter P.R., Colón-González F.J., Brainard J., Majuru B., Pedrazzoli D., Abubakar I., Dinsa G., Suhrcke M., Stuckler D., Lim T.-A. Can economic indicators predict infectious disease spread? A cross-country panel analysis of 13 European countries. Scand. J. Public Health. 2019 doi: 10.1177/1403494819852830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B.I., Ki H., Park S., Cho E., Chun B.C. Effect of climatic factors on hand, foot, and mouth disease in South Korea, 2010-2013. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupferschmidt K., Cohen J. 2020. Can China’s COVID-19 Strategy Work Elsewhere? [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C.-C., Shih T.-P., Ko W.-C., Tang H.-J., Hsueh P.-R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and corona virus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wang X.-L., Zheng X. Impact of weather factors on influenza hospitalization across different age groups in subtropical Hong Kong. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018;62:1615–1624. doi: 10.1007/s00484-018-1561-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., Ren R., Leung K.S., Lau E.H., Wong J.Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. New Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Tao J., Kan H., Qian Z., Chen A., Du Y., Liu T., Zhang Y., Qi Y., Ye J. Ambient particulate matter air pollution associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in Guangzhou, China. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2018;28:392. doi: 10.1038/s41370-018-0034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Hou X., Ren Z., Lowe R., Wang Y., Li R., Liu X., Sun J., Lu L., Song X. Climate factors and the East Asian summer monsoon may drive large outbreaks of dengue in China. Environ. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F., Zhou L., Xu Y., Zheng T., Guo Y., Wellenius G.A., Bassig B.A., Chen X., Wang H., Zheng X. Short-term effects of air pollution on daily mortality and years of life lost in Nanjing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;536:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H., Stratton C.W., Tang Y.W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan China: the mystery and the miracle. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng R.D., Dominici F., Louis T.A. Model choice in time series studies of air pollution and mortality. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. Ser. A. (Stat. Soc.) 2006;169:179–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2006.00410.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z., He Q., Lin H.-M., Kong L., Bentley C.M., Liu W., Zhou D. High temperatures enhanced acute mortality effects of ambient particle pollution in the “oven” city of Wuhan, China. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:1172–1178. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi C., Alsafi Z., O’Neill N., Khan M., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C., Agha R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int. J. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmoudi K., Bellali H., Ben-Alaya N., Saez M., Malouche D., Chahed M.K. Modeling zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis incidence in central Tunisia from 2009–2015: forecasting models using climate variables as predictors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J., Mu L., Huang J., Yu S., Chen B., Yin J. An initial investigation of the association between the SARS outbreak and weather: with the view of the environmental temperature and its variation. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2005;59:186–192. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.020180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Munster V. Stability of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) under different environmental conditions. Eurosurveillance. 2013;18 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.38.20590. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Goggins W.B., Chan E.Y. A time-series study of the association of rainfall, relative humidity and ambient temperature with hospitalizations for rotavirus and norovirus infection among children in Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;643:414–422. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., Wang B., Xiang H., Cheng Z., Xiong Y. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Lang L., Ma W., Song T., Kang M., He J., Zhang Y., Lu L., Lin H., Ling L. Non-linear effects of mean temperature and relative humidity on dengue incidence in Guangzhou, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;628:766–771. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., Zhang J., Huang L., Zhang C., Liu S., Zhao P., Liu H., Zhu L. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Changing the maximum degree of freedom to 3 for the spline function.