Abstract

Meteorological parameters are the important factors influencing the infectious diseases such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and influenza. This study aims to explore the association between Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) deaths and weather parameters. In this study, we collected the daily death numbers of COVID-19, meteorological parameters and air pollutant data from 20 January 2020 to 29 February 2020 in Wuhan, China. Generalized additive model was applied to explore the effect of temperature, humidity and diurnal temperature range on the daily death counts of COVID-19. There were 2299 COVID-19 death counts in Wuhan during the study period. A positive association with COVID-19 daily death counts was observed for diurnal temperature range (r = 0.44), but negative association for relative humidity (r = −0.32). In addition, one unit increase in diurnal temperature range was only associated with a 2.92% (95% CI: 0.61%, 5.28%) increase in COVID-19 deaths in lag 3. However, both 1 unit increase of temperature and absolute humidity were related to the decreased COVID-19 death in lag 3 and lag 5, with the greatest decrease both in lag 3 [−7.50% (95% CI: −10.99%, −3.88%) and −11.41% (95% CI: −19.68%, −2.29%)]. In summary, this study suggests the temperature variation and humidity may also be important factors affecting the COVID-19 mortality.

Keywords: COVID-19, Diurnal temperature range, Temperature, Humidity, Generalized additive model

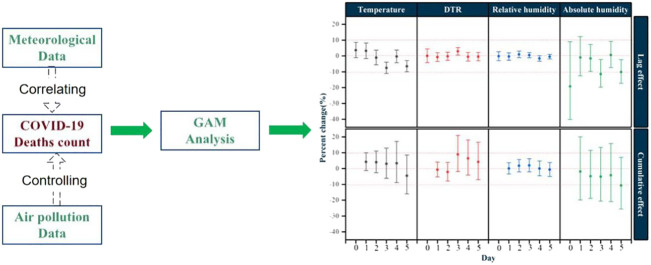

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

First study to explore the effects of meteorological factors on COVID-19 mortality

-

•

A positive association is found between daily death counts of COVID-19 and DTR.

-

•

Absolute humidity is negatively associated with daily death counts of COVID-19.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic was reported in Wuhan, China, which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Gorbalenya, 2020; Wu et al., 2020). The COVID-19 has been affirmed to have human-to-human transmissibility (C. Wang et al., 2020; M. Wang et al., 2020), which raised high attention not only in China but internationally. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that there are 118,319 confirmed cases and 4292 deaths globally until March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020a), and evaluated as global pandemic on the same day (WHO, 2020b).

In retrospect studies, the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Guangdong in 2003 gradually faded with the warming weather coming, and was basically ended until July (Wallis and Nerlich, 2005). It has been documented that the temperature and its variations might have affected the SARS outbreak (Tan, 2005). A study in Korea found that the risk of influenza incidence was significantly increased with low daily temperature and low relative humidity, a positive significant association was observed for diurnal temperature range (DTR) (Park et al., 2019). Moreover, temperature (Pinheiro et al., 2014) and DTR (Luo et al., 2013) have been linked to the death from respiratory diseases. A study demonstrated that absolute humidity had significant correlations with influenza viral survival and transmission rates (Metz and Finn, 2015). Few studies reported that the COVID-19 was related to the meteorological factors, which decreased with the temperature increasing (Oliveiros et al., 2020; C. Wang et al., 2020; M. Wang et al., 2020), but their effects on the mortality have not been reported. Therefore, we assume that the weather conditions might also contributed to the mortality of COVID-19.

As the capital of Hubei Province and one of the largest cities in Central China, Wuhan is located in the middle of the Yangtze River Delta, which has a typical subtropical, humid, monsoon climate with cold winters and warm summers (Zhang et al., 2017). The average annual temperature and rainfall are 15.8 °C–17.5 °C and 1050 mm–2000 mm, respectively (Liu et al., 2018). Besides, Wuhan owns an area of 8569 km2 and a population over 10 million (as of 2017) (2019). As of 24 March 2020, this COVID-19 has caused 16,231 deaths globally and 2524 deaths in Wuhan. Although the COVID-19 deaths may be affected by many factors, this study is to explore the effect from meteorological parameters on COVID-19 deaths using generalized additive model (GAM).

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection

Data from 20 January 2020 to 29 February 2020 in Wuhan were compiled, including daily death numbers of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), meteorological and air pollutant data. Daily death data of COVID-19 were collected from the official website of Health Commission of Hubei Province, people's Republic of China (http://wjw.hubei.gov.cn/). Daily meteorological and air pollutant data were obtained from Shanghai Meteorological Bureau and Data Center of Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People's Republic of China, respectively. Meteorological variables included daily average temperature, diurnal temperature range (DTR) and relative humidity, and air pollutant data included particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤10 μm (PM10), particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), ozone (O3). Therefore, there is no need to have ethical review.

2.2. Calculation of absolute humidity

Absolute humidity was calculated according to the previous study and was measured by vapor pressure (VP) (Davis et al., 2016a, Davis et al., 2016b). The density of water vapor, or absolute humidity [ρv (g/m3)], is the mass of moisture per total volume of air. It is associated to VP via the ideal gas law for the moist portion of the air:

| (1) |

where e is vapor pressure (VP), Rv is the gas constant for water vapor [461.53 J/(kg K)], and T is the daily ambient temperature (K). VP is a commonly used indicator of absolute humidity and is calculated from ambient temperature and relative humidity using the Clausius–Clapeyron relation (Shaman and Kohn, 2009). Briefly, we first calculated the saturation vapor pressure [es (T) (mb)] from daily ambient temperature using the following equation:

| (2) |

where es (T0) denotes saturation vapor pressure at a reference temperature T0 (273.15 K) which equals to 6.11 mb. L denotes the latent heat of evaporation for water (2257 kJ/kg). Rv is the gas constant for water vapor [461.53 J/(kg K)]. T denotes daily ambient temperature (K). Then, VP (Pa) was calculated by combining the es (T) calculated using Eq. (2) with relative humidity (RH):

| (3) |

2.3. Statistical methods

The descriptive analysis was performed for all the data. We used GAM to analyze the associations between meteorological factors (temperature, DTR, relative humidity and absolute humidity) and the daily death counts of COVID-19. The core analysis was a GAM with a quasi-Poisson link function based on the previous studies (Almeida et al., 2010; Basu et al., 2008). We first built the basic models for death outcomes without including air pollution or weather variables. We incorporated smoothed spline functions of time, which accommodate nonlinear and nonmonotonic patterns between mortality and time, thus offering a flexible modeling tool. Then, we introduced the weather variables and analyzed their effects on mortality. Akaike's information criterion was used as a measure of how well the model fitted the data. Consistent with several recent time-series studies (Cheng and Kan, 2012; Zeng et al., 2016), the penalized smoothing spline function was applied to control the effects of confounding factors, such as time trends, day-of-week and air pollution. The core GAM equation is:

where t is the day of the observation; E(Yt) is the expected number of daily mortality for COVID-19 on day t; α is the intercept; β is the regression coefficient; Xt is the daily level of weather variables on day t; s() denotes the smoother based on the penalized smoothing spline. Based on Akaike's information criterion (AIC), the 2 degrees of freedom (df) is used for time trends and 3 df for air pollutants, temperature and relative humidity; DOW is a categorical variable indicating the date of the week.

After establishing the core model, we considered the lag effects of weather conditions on death of COVID-19, and examined the potentially lagged effects, i.e., single day lag (from lag 0 to lag 5) and multiple-day average lag (from lag 01 to lag 05) (Kan et al., 2007). The exposure and response correlation curves between weather variables and COVID-19 mortality were fitted using a spline function in the GAM. We also performed a sensitivity analysis by changing the df of the penalized smoothing spline function from 2 to 9 for calendar time and from 3 to 8 for temperature and humidity.

All the statistical analyses were two-sided at a 5% level of significance. All analyses were conducted using R software (version 3.5.3) with the “mgcv” package (version 1.8-27). The effect estimates were expressed as the percentage changes and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in daily death of COVID-19 associated with per 1 unit increase in weather variables.

3. Results

3.1. Description of COVID-19 daily mortality, meteorological variables and air pollutants

Table 1 showed the descriptive statistics for daily deaths of COVID-19, meteorological variables and air pollutants. During the study period (January 20, 2020 to February 29, 2020), there were 2299 COVID-19 deaths in Wuhan. On average, there were approximately 56 deaths of COVID-19 per day. Temperatures ranged from 1.8 °C to 18.7 °C, and DTR ranged from 2 °C to 17.5 °C. Average temperature and DTR during this period were 7.44 °C and 9.15 °C, respectively. The relative humidity and absolute humidity were 59%–97% with an average 82.24% and 4.27 g/m3–11.63 g/m3 with an average 6.69 g/m3, respectively. The mean concentrations of PM2.5, PM10, NO2, SO2, O3, and CO were 44.68 μg/m3, 52.56 μg/m3, 23.02 μg/m3, 7.29 μg/m3, 73.76 μg/m3 and 0.91 mg/m3, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary of COVID-19 death counts, meteorological data and air pollutants.

| Variables | Daily measures |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± S.D. | Min | P 25 | Median | P75 | Max | |

| Mortality counts | 56.07 ± 42.69 | 2.00 | 25.00 | 49.00 | 76.00 | 216.00 |

| Meteorological factors | ||||||

| Temperature (°C) | 7.44 ± 3.96 | 1.80 | 4.40 | 6.50 | 9.90 | 18.70 |

| DTR (°C) | 9.15 ± 4.74 | 2.00 | 4.70 | 8.70 | 14.00 | 17.50 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 82.24 ± 8.51 | 59.00 | 77.00 | 83.00 | 88.00 | 97.00 |

| Absolute humidity (g/m3) | 6.69 ± 1.78 | 4.27 | 5.38 | 6.30 | 7.51 | 11.63 |

| Concentration of air pollutants | ||||||

| PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 44.68 ± 23.97 | 9.00 | 28.00 | 41.00 | 64.00 | 97.00 |

| PM10 (μg/m3) | 52.56 ± 26.01 | 12.00 | 32.00 | 48.00 | 69.00 | 116.00 |

| NO2 (μg/m3) | 23.02 ± 11.77 | 10.00 | 16.00 | 20.00 | 28.00 | 76.00 |

| SO2 (μg/m3) | 7.29 ± 2.28 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 7.00 | 9.00 | 13.00 |

| CO (mg/m3) | 0.91 ± 0.21 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 1.40 |

| O3 (μg/m3) | 73.76 ± 21.50 | 39.00 | 53.00 | 74.00 | 94.00 | 110.00 |

COVID-19, Corona Virus Disease 2019; SD, standard deviance; Min, minimum; P25, 25th percentile; P75, 75th percentile; Max, maximum; DTR, diurnal temperature range; PM2.5, particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm; PM10, particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤10 μm; NO2, nitrogen dioxide; SO2, sulfur dioxide; CO, carbon monoxide; O3, ozone.

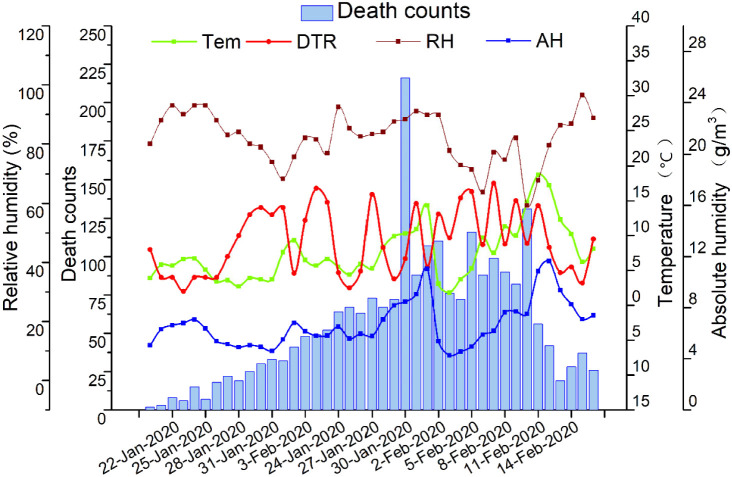

Fig. 1 presented the temporal pattern of daily mortality of COVID-19 and meteorological factor levels in the study period, showing the daily death number of COVID-19 had a similar pattern with temperature and absolute humidity.

Fig. 1.

Temporal pattern of COVID-19 daily mortality and meteorological factor levels in Wuhan, China, from 20 January to 29 February 2020. COVID-19, Corona Virus Disease 2019; Tem, temperature; DTR, diurnal temperature range; RH, relative humidity; AH, absolute humidity.

3.2. Correlation between COVID-19 mortality and meteorological factors and air pollutants

The correlation coefficients between death counts of COVID-19, meteorological measures and air pollutant concentrations were presented in Table 2 . The mortality counts of COVID-19 were negatively associated with relative humidity (r = −0.32), PM2.5 (r = −0.53) and PM10 (r = −0.45). A positive association with COVID-19 daily mortality was observed for DTR (r = 0.44) and SO2 (r = 0.31).

Table 2.

Spearman's correlation between meteorological factors and air pollutants and COVID-19 mortality.

| Mortality | Tem | DTR | RH | AH | PM2.5 | PM10 | NO2 | SO2 | CO | O3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Tem | 0.30 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| DTR | 0.44⁎ | −0.06 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| RH | −0.32⁎ | −0.08 | −0.59⁎ | 1.00 | |||||||

| AH | 0.16 | 0.90⁎ | −0.30 | 0.31⁎ | 1.00 | ||||||

| PM2.5 | −0.53⁎ | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.20 | −0.05 | 1.00 | |||||

| PM10 | −0.45⁎ | 0.11 | 0.06 | −0.25 | 0.01 | 0.97⁎ | 1.00 | ||||

| NO2 | −0.04 | 0.21 | 0.33⁎ | −0.39⁎ | −0.03 | 0.63⁎ | 0.65⁎ | 1.00 | |||

| SO2 | 0.31⁎ | 0.41⁎ | 0.59⁎ | −0.69⁎ | 0.08 | 0.31⁎ | 0.40⁎ | 0.71⁎ | 1.00 | ||

| CO | −0.06 | 0.57⁎ | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.51⁎ | 0.52⁎ | 0.56⁎ | 0.59⁎ | 0.52⁎ | 1.00 | |

| O3 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.75⁎ | −0.80⁎ | −0.26 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.33⁎ | 0.62⁎ | 0.01 | 1.00 |

COVID-19, Corona Virus Disease 2019; Tem, temperature; DTR, diurnal temperature range; RH, relative humidity; AH, absolute humidity; PM2.5, particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm; PM10, particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤10 μm; NO2, nitrogen dioxide; SO2, sulfur dioxide; CO, carbon monoxide; O3, ozone.

P < 0.05.

3.3. Effects of temperature, humidity and DTR on COVID-19 mortality

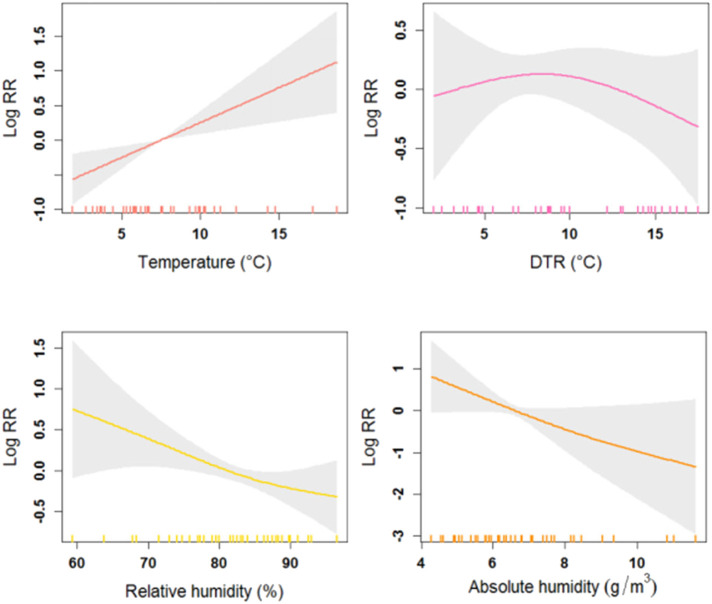

Fig. 2 showed the exposure-response relationship curves between meteorological factors and COVID-19 mortality at the same day (lag 0). Generally, the curves tended to be not associated with COVID-19 mortality for DTR but were strongly positive for temperature. In addition, the curves associated with relative humidity and absolute humidity presented similar linear trends, which indicated that the higher level of humidity might cause decrease in the COVID-19 mortality. To confirm these results, lag and cumulative effects were discussed in the following analysis.

Fig. 2.

The exposure-response curves of meteorological factors and COVID-19 daily mortality counts in Wuhan, China, from 20 January to 29 February 2020. The X-axis is the concurrent day meteorological data, Y-axis is the predicted log relative risk (RR), is shown by the solid line, and the dotted lines represent the 95% confidence interval (CI). COVID-19, Corona Virus Disease 2019; DTR, diurnal temperature range.

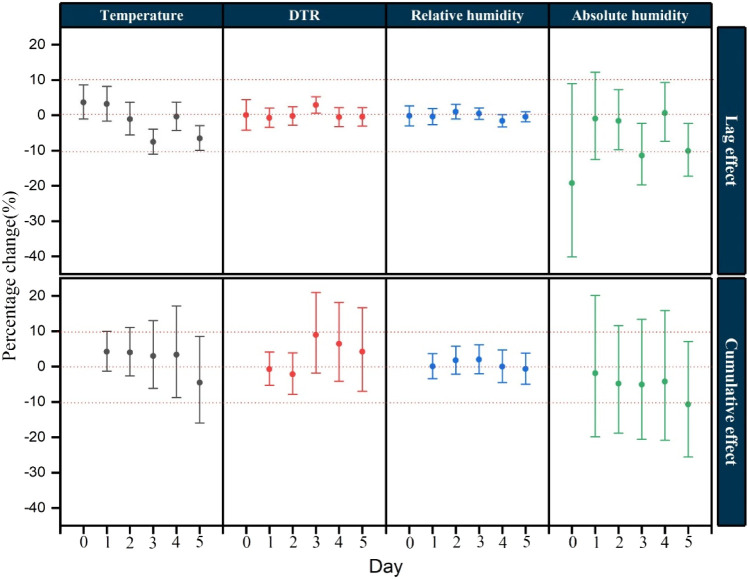

Fig. 3 displayed the percentage changes of COVID-19 mortality with per 1 unit increase in meteorological factor levels with different lag days in the models. DTR was significantly associated with the increased COVID-19 mortality, while temperature and absolute humidity with the decreased COVID-19 mortality, after controlling the effects of air pollution and other factors. Each 1 unit increase in DTR was only associated with a 2.92% (95% CI: 0.61%, 5.28%) increase in COVID-19 death counts in lag 3. However, both per 1 unit increase of temperature and absolute humidity were related to the decreased COVID-19 death counts in lag 3 and lag 5, with the greatest decrease both in lag 3 [−7.50% (95% CI: −10.99%, −3.88%) and − 11.41% (95% CI: −19.68%, −2.29%)]. For cumulative effect, no substantial result was observed in this study.

Fig. 3.

Percentage change (95% confidence interval) of COVID-19 daily mortality with per 1 unit increase in meteorological factors for different lag days in the models in Wuhan, China, from 20 January to 29 February 2020. COVID-19, Corona Virus Disease 2019; DTR, diurnal temperature range.

4. Discussion

COVID-19 outbreak has caused great health burden around the world. In this study, we examined the relationship between meteorological factors and COVID-19. Our results showed significant positive effect of DTR on the daily mortality of COVID-19, and a significant negative association between COVID-19 mortality and ambient temperature as well as absolute humidity. The results indicate that the effects of DTR and humidity should also be paid attention when estimating the death causes of COVID-19.

Our study demonstrated a negative association between COVID-19 mortality and temperature, while a positive association for DTR. The results are consistent with the other studies. Couple of studies reported that respiratory diseases mortality increased with decreasing temperature (Fallah and Mayvaneh, 2016), and was strongly associated with low temperature (Dadbakhsh et al., 2017; Gómez-Acebo et al., 2013; Macfarlane, 1977). While another study found that both cold and heat effects might have adverse impacts on respiratory mortality (Li et al., 2019). Otherwise, the study conducted in 30 East Asian cities showed that increased DTR was associated with increased risk of mortality for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases (Kim et al., 2016). In the cold season, the cumulative relative risk of non-accidental, respiratory and cardiovascular death increased at high DTR values in Tabriz (Sharafkhani et al., 2019). A time-series study conducted in Shanghai about the effect of DTR on daily chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) mortality showed that each 1 °C elevation in the 4-day moving average for DTR accounted for 1.25% of increased risk of COPD mortality (Song et al., 2008). A review for cold exposure and immune function reported that lower temperature may repress the immune function (Shephard and Shek, 1998). In particular, our previous finding suggested that the phagocytic function of pulmonary alveolar macrophages declined under cold stress in vitro experiment (Luo et al., 2017). Breathing cold air can lead to bronchial constriction, which may promote susceptibility to pulmonary infection (Martens, 1998). Additionally, since SARS-CoV-2 is sensitive to heat, and high temperature makes it difficult to survive, not to mention the beneficial factors for virus transmission like indoor crowding and poor ventilation in cold days (Bunker et al., 2016). Also, cold temperature has been discovered to be associated with the reduction of lung function and increases in exacerbations for people with COPD (Donaldson et al., 1999). DTR represents a stable measure of temperature, which is an indicator of temperature variability to evaluate effects on human health, including mortality and morbidity (Easterling et al., 1997). Also, abrupt temperature changes may add to the burden of cardiac and respiratory system causing cardiopulmonary events and high DTR levels may be a source of environmental stress (Sharafkhani et al., 2019). It is said that the windows of inpatient wards were asked to remain open for 24 h a day and avoid using air conditioning in Wuhan hospitals due to ventilation necessity, therefore the indoor variation trend of meteorological factors could be very close to the outdoor environment. Concerning about this condition and our results, it is reasonable to sustain a stable and comfortable environment for the patients during therapy.

Researchers confirmed that respiratory infection was enhanced during unusually cold and low humidity conditions (Davis et al., 2016a, Davis et al., 2016b), indicating low humidity might also be an important risk factor for respiratory diseases. A 25-year study found that humidity was an important determinant of mortality, and low-humidity levels might cause a large increase in mortality rates, potentially by influenza-related mechanisms (Barreca, 2012), similar to a study carried out in the United States (Barreca and Shimshack, 2012). Consistent to these findings, our results also indicate that the risk of dying from COVID-19 decreases only with absolute humidity increasing. Breathing dry air could cause epithelial damage and/or reduction of mucociliary clearance, and then lead to render the host more susceptible to respiratory virus infection; The formation of droplet nuclei is essential to transmission, but exhaled respiratory droplets settle very rapidly at high humidity so that it is hard to contribute to influenza virus spread (Lowen et al., 2007). Moreover, the transmission of pandemic influenza virus is efficient under cold, dry conditions (Steel et al., 2011), and influenza virus survival rate increased markedly in accordance with decreasing of absolute humidity (Shaman et al., 2009), which may be very similar to coronavirus. Therefore, the increase of COVID-19 mortality may also be related to the lower humidity in winter.

However, many limitations should not be ignored. Firstly, there are some other important factors that may affect the COVID-19 mortality, such as government interventions, medical resources and so on. Therefore, these issues should be examined in future studies. Secondly, ecologic time-series study design was adopted in the study, which might have ecologic fallacy to some degree. Furthermore, it is difficult to obtain the meteorological and air pollution data at the individual level, although the outdoor and indoor air environment might be similar due to the air conditioner off using and window opening for 24 h in the hospital patient wards during COVID-19 therapy. Nevertheless, this study showed that DTR and humidity might affect the mortality of COVID-19 in Wuhan, which deserves further investigation from a larger range of studying area.

5. Conclusion

This is the first study to investigate the effects of temperature, DTR and humidity on the daily mortality of COVID-19 in Chinese population. Our finding shows that the daily mortality of COVID-19 is positively associated with DTR but negatively with absolute humidity. In summary, this study suggests the temperature variation and humidity may also be important factors affecting the COVID-19 mortality. And our results suggest that it is reasonable to sustain a stable and comfortable environment for the patients during therapy.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Corona Virus Disease 2019

- Tem

temperature

- DTR

diurnal temperature range

- RH

relative humidity

- AH

absolute humidity

- PM2.5

particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm

- PM10

particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤10 μm

- NO2

nitrogen dioxide

- SO2

sulfur dioxide

- CO

carbon monoxide

- O3

ozone

- GAM

generalized additive model

- CI

confidence interval

- RR

relative risk

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of supporting data

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the websites.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (4187050043) and the Novel Coronavirus Disease Science and Technology Major Project of Gansu Province.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yueling Ma: Writing - original draft, Software. Yadong Zhao: Supervision. Jiangtao Liu: Methodology. Xiaotao He: Data curation. Bo Wang: Formal analysis. Shihua Fu: Validation. Jun Yan: Investigation. Jingping Niu: Project administration. Ji Zhou: Visualization. Bin Luo: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Editor: Jianmin Chen

References

- Almeida S.P., Casimiro E., Calheiros J. Effects of apparent temperature on daily mortality in Lisbon and Oporto, Portugal. Environ. Health. 2010;9(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anon. Vol. 2020. 2019. Wuhan Statistical Yearbook 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barreca A.I. Climate change, humidity, and mortality in the United States. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2012;63(1):19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreca A.I., Shimshack J.P. Absolute humidity, temperature, and influenza mortality: 30 years of county-level evidence from the United States. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012;176(suppl_7):S114–S122. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu R., Feng W., Ostro B.D. Characterizing temperature and mortality in nine California counties. Epidemiology. 2008:138–145. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31815c1da7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunker A., Wildenhain J., Vandenbergh A., Henschke N., Rocklöv J., Hajat S., Sauerborn R. Effects of air temperature on climate-sensitive mortality and morbidity outcomes in the elderly; a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence. Ebiomedicine. 2016;6:258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Kan H. Effect of the interaction between outdoor air pollution and extreme temperature on daily mortality in Shanghai, China. J. Epidemiol. 2012;22(1):28–36. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20110049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadbakhsh M., Khanjani N., Bahrampour A., Haghighi P.S. Death from respiratory diseases and temperature in Shiraz, Iran (2006–2011) Int. J. Biometeorol. 2017;61(2):239–246. doi: 10.1007/s00484-016-1206-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R.E., Dougherty E., McArthur C., Huang Q.S., Baker M.G. Cold, dry air is associated with influenza and pneumonia mortality in Auckland, New Zealand. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses. 2016;10(4):310–313. doi: 10.1111/irv.12369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R.E., McGregor G.R., Enfield K.B. Humidity: a review and primer on atmospheric moisture and human health. Environ. Res. 2016;144:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson G.C., Seemungal T., Jeffries D.J., Wedzicha J.A. Effect of temperature on lung function and symptoms in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. Respir. J. 1999;13(4):844–849. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13d25.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterling D.R., Horton B., Jones P.D., Peterson T.C., Karl T.R., Parker D.E., Salinger M.J., Razuvayev V., Plummer N., Jamason P. Maximum and minimum temperature trends for the globe. Science. 1997;277(5324):364–367. [Google Scholar]

- Fallah G.G., Mayvaneh F. Effect of air temperature and universal thermal climate index on respiratory diseases mortality in Mashhad, Iran. Arch. Iran. Med. 2016;19(9):618–624. (doi:0161909/AIM.004) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Acebo I., Llorca J., Dierssen T. Cold-related mortality due to cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and cancer: a case-crossover study. Public Health. 2013;127(3):252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbalenya A.E. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus–the species and its viruses, a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. BioRxiv. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.07.937862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kan H., London S.J., Chen H., Song G., Chen G., Jiang L., Zhao N., Zhang Y., Chen B. Diurnal temperature range and daily mortality in Shanghai, China. Environ. Res. 2007;103(3):424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Shin J., Lim Y., Honda Y., Hashizume M., Guo Y.L., Kan H., Yi S., Kim H. Comprehensive approach to understand the association between diurnal temperature range and mortality in East Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;539:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.08.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Zhou M., Yang J., Yin P., Wang B., Liu Q. Temperature, temperature extremes, and cause-specific respiratory mortality in China: a multi-city time series analysis. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 2019;12(5):539–548. doi: 10.1007/s11869-019-00670-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Ma Y., Gong W., Zhang T., Shi Y. 2018. Study of Haze Pollution During Winter in Wuhan, China. Paper Presented at: IGARSS 2018–2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IEEE) [Google Scholar]

- Lowen A.C., Mubareka S., Steel J., Palese P. Influenza virus transmission is dependent on relative humidity and temperature. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(10):1470–1476. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Zhang Y., Liu T., Rutherford S., Xu Y., Xu X., Wu W., Xiao J., Zeng W., Chu C., Ma W. Lagged effect of diurnal temperature range on mortality in a subtropical megacity of China. PLoS One. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B., Liu J., Fei G., Han T., Zhang K., Wang L., Shi H., Zhang L., Ruan Y., Niu J. Impact of probable interaction of low temperature and ambient fine particulate matter on the function of rats alveolar macrophages. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017;49:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane A. Daily mortality and environment in English conurbations. Air pollution, low temperature, and influenza in Greater London. Br. J. Prev. Soc. Med. 1977;31(1):54–61. doi: 10.1136/jech.31.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens W.J.M. Climate change, thermal stress and mortality changes. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998;46(3):331–344. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz J.A., Finn A. Influenza and humidity – why a bit more damp may be good for you! J. Inf. Secur. 2015;71:S54–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveiros B., Caramelo L., Ferreira N.C., Caramelo F. Role of temperature and humidity in the modulation of the doubling time of COVID-19 cases. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.05.20031872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.E., Son W.S., Ryu Y., Choi S.B., Kwon O., Ahn I. Effects of temperature, humidity, and diurnal temperature range on influenza incidence in a temperate region. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses. 2019;14(1):11–18. doi: 10.1111/irv.12682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro S.D.L.L., Saldiva P.H.N., Schwartz J., Zanobetti A. Isolated and synergistic effects of PM10 and average temperature on cardiovascular and respiratory mortality. Rev. Saude Publica. 2014;48(6):881–888. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048005218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaman J., Kohn M. Absolute humidity modulates influenza survival, transmission, and seasonality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106(9):3243–3248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806852106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaman J., Kohn M., Singer B.H. Absolute humidity modulates influenza survival, transmission, and seasonality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106(9):3243–3248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806852106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharafkhani R., Khanjani N., Bakhtiari B., Jahani Y., Tabrizi J.S., Tabrizi F.M. Diurnal temperature range and mortality in Tabriz (the northwest of Iran) Urban Clim. 2019;27:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2018.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shephard R.J., Shek P.N. Cold exposure and immune function. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1998;76(9):828–836. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-76-9-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G., Chen G., Jiang L., Zhang Y., Zhao N., Chen B., Kan H. Diurnal temperature range as a novel risk factor for COPD death. Respirology. 2008;13:1066–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel J., Palese P., Lowen A.C. Transmission of a 2009 pandemic influenza virus shows a sensitivity to temperature and humidity similar to that of an H3N2 seasonal strain. J. Virol. 2011;85(3):1400–1402. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02186-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J. An initial investigation of the association between the SARS outbreak and weather: with the view of the environmental temperature and its variation. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2005;59(3):186–192. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.020180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis P., Nerlich B. Disease metaphors in new epidemics: the UK media framing of the 2003 SARS epidemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005;60(11):2629–2639. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Horby P.W., Hayden F.G., Gao G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Jiang A., Gong L., Luo L., Guo W., Li C., Zheng J., Li C., Yang B., Zeng J. Temperature significant change COVID-19 transmission in 429 cities. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.22.20025791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report – 51. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020(3) 2020. WHO Characterizes COVID-19 as a Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y., Wang W., Song Z., Hu Y., Tao Z., Tian J., Pei Y., Yuan M., Zhang Y., Dai F., Liu Y., Wang Q., Zheng J., Xu L., Holmes E.C., Zhang Y. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q., Li G., Cui Y., Jiang G., Pan X. Estimating temperature-mortality exposure-response relationships and optimum ambient temperature at the multi-city level of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016;13(3):279. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13030279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Feng R., Wu R., Zhong P., Tan X., Wu K., Ma L. Global climate change: impact of heat waves under different definitions on daily mortality in Wuhan, China. Glob. Health Res. Policy. 2017;2(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s41256-017-0030-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the websites.