Abstract

This study examines changes in mortality rate ratios and life-years lost for both external and natural causes over 20 years for specific mental disorders.

People with mental disorders have increased mortality rates and reduced life expectancies.1,2 The life-years lost (LYLs), which estimates life expectancy for people with a disorder compared with the general population,1,3,4 have been estimated to be 10 and 7 years, respectively, for men and women with any mental disorder.1,2 For schizophrenia, LYLs related to suicide and unintentional deaths (ie, external causes) had fallen over a 20-year period, but these gains were offset by worsening LYLs related to deaths from general medical conditions (ie, natural causes).5 The aim of this Research Letter is to examine changes in mortality rate ratios (MRRs) and LYLs for both external and natural causes over 20 years for specific mental disorders.

Methods

Specific details have been described elsewhere.2 We conducted a cohort study comprising all 7 369 926 people living in Denmark followed up from 1995 to 2015. We used national registers to consider all mental disorders as defined by the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) F-subchapters and classified deaths into natural and external causes. The Danish Data Protection Agency and the Danish Health Data Authority approved this study. Informed consent is not required for register-based studies in Denmark. We estimated MRRs using Poisson regression models, adjusting for sex and age and including an interaction term with calendar time. Differences in remaining life expectancy after diagnosis were estimated as excess LYLs2,3,4 (divided into natural and external causes) between those with each disorder and the general Danish population (matched on sex and age).

Results

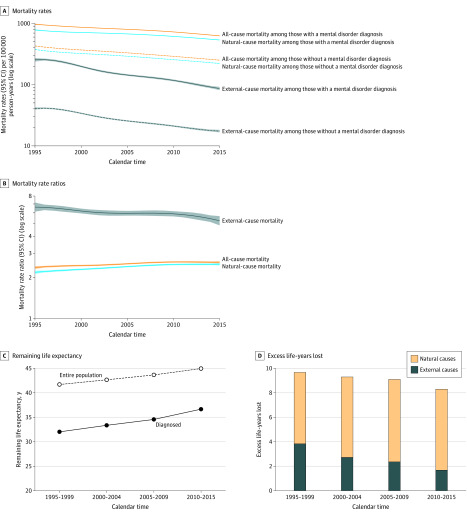

There were 762 419 people diagnosed as having a mental disorder and 1 122 351 deaths during the period of observation. Mortality rates decreased over time for those with any diagnosed mental disorder, as well as for those without a diagnosis (Figure 1A). Despite these improvements, MRRs between the 2 groups increased from 2.38 (95% CI, 2.32-2.44) in 1995 to 2.60 (95% CI, 2.55-2.65) in 2015 (Figure 1B). For external causes of death, MRRs decreased from 6.64 (95% CI, 6.15-7.17) to 5.27 (95% CI, 4.87-5.70), while MRRs for natural causes increased from 2.19 (95% CI, 2.14-2.25) to 2.52 (95% CI, 2.47-2.56) (Figure 1A and B). Remaining life expectancy after disease diagnosis increased 4.6 years from 32.0 to 36.6 years; however, remaining life expectancy also increased in the general population of same age and sex by 3.2 years (from 41.7 to 44.9 years) (Figure 1C). The life expectancy gap between the 2 periods was therefore shortened by 1.4 years; excess LYLs were 9.7 years in 1995 to 1999 (5.8 and 3.8 years owing to natural and external causes, respectively) and 8.3 years in 2010 to 2015 (6.6 and 1.7 years owing to natural and external causes), respectively (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Mortality Rates Ratios and Life-Years Lost.

Mortality rates for people with and without a diagnosis of a mental disorder (A) and mortality rate ratios depending on calendar year (B) for all-cause mortality, and for natural and external causes of death; remaining life expectancy after disease diagnosis for people with a mental disorder and a sex- and age-matched general population (C); and excess life-years lost (overall and owing to natural and external causes of death) for people with mental disorders (D).

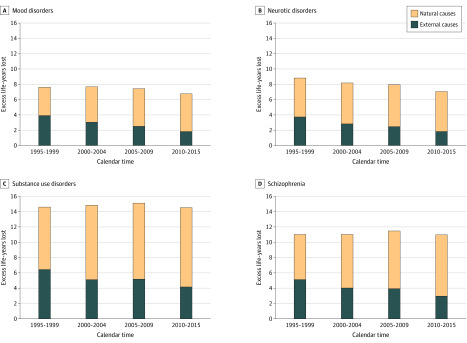

Figure 2 shows some disorder-specific LYLs divided into natural and external causes of death. The life expectancy gap was reduced for mood disorders (0.8 years), neurotic disorders (1.7 years), and personality disorders (0.9 years); remained similar for schizophrenia and substance use disorders; and increased for organic disorders (1.1 years). Results were similar for men and women.

Figure 2. Excess Life-Years Lost (Overall and Owing to Natural and External Causes of Death) Over Calendar Time for People With Mood Disorders (A), Neurotic Disorders (B), Substance Use Disorders (C), and Schizophrenia (D).

Discussion

Mortality rates for people experiencing mental disorders decreased in Denmark from 1995 to 2015. However, for natural causes of death, those with mental disorders did not reflect the benefits seen in the general population. Consequently, life lost owing to natural causes increased. While the overall excess LYLs were substantial (8.3 years in 2010-2015), life expectancy increased an additional 1.4 years for those with mental disorders compared with the general population, thus reducing the gap. Nevertheless, for some disorders, eg, schizophrenia and substance use disorders, the life expectancy gap did not change. While this register-based study is based on the entire Danish population and information is collected prospectively, it has some important limitations,2 eg, only mental disorders registered in hospitals could be identified. These findings support the hypothesis that service improvements may have reduced mortality owing to suicide and unintentional injury,6 but similar benefits are not apparent in natural causes of death, which suggests that interventions associated with promoting a healthier lifestyle and optimizing the general medical care of those with mental disorders warrant added investment.

References

- 1.Erlangsen A, Andersen PK, Toender A, Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Canudas-Romo V. Cause-specific life-years lost in people with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(12):937-945. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30429-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Agerbo E, et al. A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10211):1827-1835. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32316-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen PK. Life years lost among patients with a given disease. Stat Med. 2017;36(22):3573-3582. doi: 10.1002/sim.7357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plana-Ripoll O, Canudas-Romo V, Weye N, Laursen TM, McGrath JJ, Andersen PK. lillies: An R package for the estimation of excess Life Years Lost among patients with a given disease or condition. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0228073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laursen TM, Plana-Ripoll O, Andersen PK, et al. Cause-specific life years lost among persons diagnosed with schizophrenia: Is it getting better or worse? Schizophr Res. 2019;206:284-290. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu NH, Daumit GL, Dua T, et al. Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: a multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):30-40. doi: 10.1002/wps.20384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]