Abstract

We believe a point-of-care (PoC) device for the rapid detection of the 2019 novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is crucial and urgently needed. With this perspective, we give suggestions regarding a potential candidate for the rapid detection of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), as well as factors for the preparedness and response to the outbreak of the COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Wuhan, 2019 novel Coronavirus, Point-of-care detection, SARS-CoV-2, (Loop-mediated isothermal amplification) LAMP assay, (polymerase chain reaction) PCR

1. Introduction

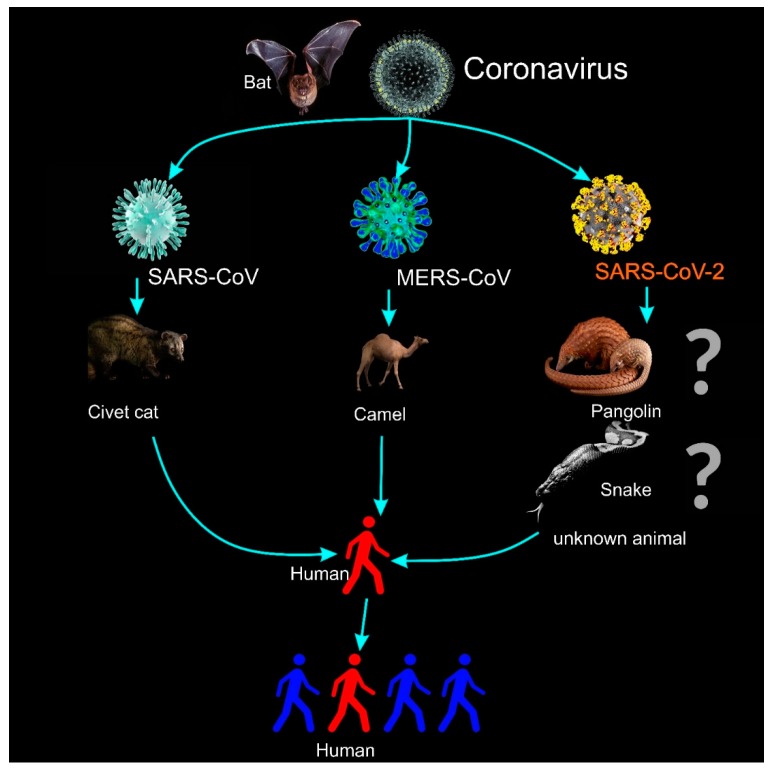

On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global public health emergency [1] over the outbreak of the new coronavirus, called the 2019 novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), which originated in Wuhan City, in the Hubei Province of China. On 11 February, WHO officially named the disease as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [2]. Human-to-human transmission (Figure 1) has been confirmed by WHO and by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States [3], with evidence of person-to-person transmission from three different cases outside China, namely in the US [4], Germany [5], and Vietnam [6]. COVID-19 has continuously spread to 104 countries; the number of confirmed infections reached 109,343 on 9 March 2020 [7], and the death toll in China has overtaken the SARS epidemic of 2002–2003 and has risen to 3,100 [2]. To slow down the spread of COVID-19, at least 50 million people in China have been placed under lockdown [8]. On 8 March 2020, Italy also undertook the same measures, with the northern part of the country placed under lockdown, affecting 16 million people [9]. The definition of coronaviruses is listed in Table 1. The reproduction number R0 (i.e., the average number of secondary cases generated by a typical infectious individual) is estimated to be 2.68, and the doubling time is estimated to be 6.4 days [10].

Figure 1.

The illustration for the transmission of coronaviruses and the 2019 novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV or SARS-CoV-2 [11]). Current studies have suggested that the intermediate carriers may be snakes [12] or pangolins [13], but according to WHO the real source is still unknown [14,15].

Table 1.

Coronaviruses (CoVs) and 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2).

| Virus | Description |

|---|---|

| Coronaviruses (CoVs): | A large and diverse family of enveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses, with a ~26–32 kilobase genome [16]. The Coronaviridae cover a broad host range, infecting many mammalian and avian species, and induce upper respiratory, gastrointestinal, hepatic, and central nervous system diseases [17]. In the last few decades, coronaviruses have been shown to be capable of also infecting humans. The outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, and, more recently, Middle-East respiratory syndrome (MERS) have proved the lethality of CoVs when they cross the species barrier and infect humans [18]. |

| 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2 [11]): | A new zoonotic human coronavirus, which was reported and announced by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) on 9 January 2020 [19]. In spite of the fact that the initial infected cases have been associated with the Huanan South China Seafood Market, the source of COVID-19 is still unknown (Figure 1). On 30 January 2020, the WHO declared a global public health emergency regarding the outbreak of COVID-19. On the 11 March 2020, the WHO declared the outbreak of COVID-19 a pandemic. |

2. The Need for a Rapid Detection Method and Portable Detection Devices

The manifestation of the COVID-19 infection is highly nonspecific, including respiratory symptoms, fever, cough, dyspnea, and viral pneumonia [20]. Thus, diagnostic tests specific to this infection are urgently required to confirm suspected cases, screen patients, and conduct virus surveillance.

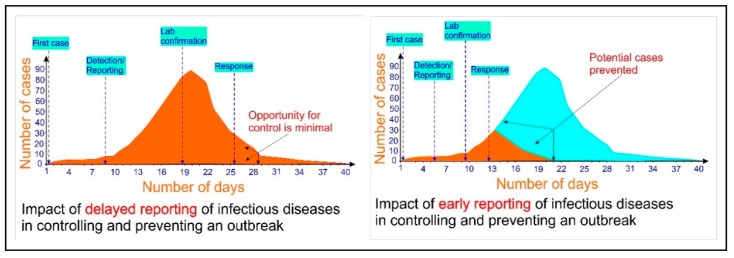

In this scenario, a point-of-care (PoC) device (i.e., a rapid, robust, and cost-efficient device that can be used onsite and in the field, and which does not necessarily require a trained technician to operate [21]) is crucial and urgently needed for the detection of COVID-19. Figure 2 shows the dramatic impact of early detection of infectious diseases in controlling an outbreak [22,23,24].

Figure 2.

The dramatic impact of the rapid detection of infectious diseases in controlling and preventing an outbreak (adapted to WHO document [22] and References [23,24]).

Such a PoC device can be used in (but is not limited to) an emergency situation, such as the Diamond Princess cruise ship case. Recently, it was reported that the Diamond Princess cruise ship has been quarantined in Yokohama, Japan, due to a serious spreading of COVID-19 on this cruise, with at least 454 infected cases out of 3,700 passengers and crew (reported by WHO [7], 17 February 2020). The detection of COVID-19 may not have been prompt enough as they did not have enough test kits to diagnose all the passengers on the ship in order to timely respond to the rapid spreading of the disease [25].

The current standard molecular technique that is now being used to detect COVID-19 is the real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR). This protocol has been documented and available online on the WHO website since 17 January 2020 [26]. The testing procedure includes: (i) specimen collection; (ii) packing (storage) and shipment of the clinical specimens; (iii) (good) communication with the laboratory and providing needed information; (iv) laboratory testing; (v) reporting the results. This rRT-PCR technique requires sophisticated laboratory equipment that is often located at a central laboratory (biosafety level 2 or above) [4,26,27]. Sample transportation is inevitable. As a consequence, the time required to obtain the results can be up to 2 or 3 days. In the case of a public health emergency such as the COVID-19 outbreak, this time-consuming process of sample testing is not only extremely disadvantageous, but also dangerous since the virus needs to be contained. In addition, commercial PCR-based methods are expensive and depend upon technical expertise, and the presence of viral RNA or DNA does not always reflect acute disease [28,29,30]. Furthermore, using PCR, codetection with other respiratory viruses is frequently encountered in coronaviruses (CoVs), and the contribution of positive CoV PCR results to disease severity is not always explicitly exhibited [28,29,30]. Furthermore, as of 2 February 2020 in the United States, as mentioned in the Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens from Persons Under Investigation (PUIs) for 2019 Novel Coronavirus, the diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC. From 4 February 2020 onwards, COVID-19 tests can also be done at laboratories designated by CDC. Likewise in China, where the outbreak is ongoing, samples had to be sent to Beijing for testing, as reported on 31 January 2020 [31]. On 4 February 2020, China’s own CDC deployed a mobile biosafety laboratory to Wuhan in the Hubei Province to assist with the response [32,33]. On 5 February 2020, an emergency test laboratory (biosafety level 2) run by BGI Genomics, Global Heartquare: Shenzhen, China was set up in Wuhan in the Hubei Province to assist the COVID-19 epidemic [34].

3. A Potential Candidate for Rapid Detection of SARS-CoV-2: Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Assays in PoC Devices

In order to overcome the current time-consuming and laborious detection technique using RT-qPCR, an alternative molecular amplification technique should be deployed. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) reaction is a novel nucleic acid amplification technique that amplifies DNA with high specificity, efficiency, and rapidity under isothermal conditions. This method uses a set of four specially designed primers, and a DNA polymerase with strand displacement activity [35] to synthesize target DNA up to 109 copies in less than an hour at a constant temperature of 65 °C. The final products are stem-loop DNAs with multiple inverted repeats of the target, bearing structures with a cauliflower-like appearance. LAMP has high specificity and sensitivity and is simple to perform; hence, soon after its initial development it became an enormously popular isothermal amplification method in molecular biology, with application in pathogen detection. LAMP uses strand-displacement polymerases instead of heat denaturation to generate a single-stranded template; hence, it has the advantage of running at a constant temperature, simultaneously reducing the cumbersomeness of a thermocycler as well as the energy required. LAMP technology is proven to be more stable [36] and more sensitive [37] in detection compared to PCR. Other advantages of LAMP compared to those of PCR are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

| PCR | LAMP |

|---|---|

| Thermal cycling (Multiple heating and cooling cycle; hence, bulky and cumbersome). |

Isothermal and continuous amplification (Smaller, simpler, hence portable). |

| Always requires sample concentration and preparation (Time-consuming). |

For virus detection, for example, influenza [40] or human norovirus, LAMP assay offers one-step detection [41]. Sample preparation steps are simplified. |

| Multiple protocols (Complicated and requires a skilled technician). |

Single protocol (Faster). |

| Inhibitors hinder the reaction. | Tolerate inhibitors and more stable. |

| Diagnostic sensitivity (95%) is currently reported lower than LAMP [33,41,42]. | Diagnostic sensitivity > 95%. |

| Established technique. | Applications using LAMP assays are being explored. |

We believe that the LAMP assay could be a potential candidate for the point-of-care device application in the detection of COVID-19. An example of using LAMP in a point-of-care device for the detection of a zoonotic virus causing respiratory symptoms such as the Avian influenza virus (AIV) is the VIVALDI (Veterinary validation of point-of-care diagnostic instrument) project [38]. With PoC devices such as the VETPOD [38] (Veterinary, Portable, Onsite Detection), in the VIVALDI project, detection time can be less than 1 h. Besides PoC devices using disposable polymer chips and LAMP assays, as in the VETPOD of the VIVALDI project, a lateral flow strip (LFS) would also be a suitable candidate for the rapid and on-site detection of COVID-19. A device such as COVID-19 IgM/IgG Rapid Test of BioMedomics is a good example [39]. The sensitivity of the COVID-19 IgM/IgG Rapid Test is 88.66%, which is expected to be lower than the sensitivity of tests based on LAMP-reaction assays (>95%). Therefore, a combination of LFS and LAMP into one device could be an excellent candidate for PoC testing of COVID-19.

4. Other Important Factors in Fighting COVID-19

Furthermore, alongside detecting and containing the virus, for the sake of a public health response regarding the dynamics of the outbreak, the socio-economic impact of COVID-19 is equally in urgent need. WHO announced that to fight the further spread of COVID-19, the international community has launched a US$675 million preparedness and response plan from February through April 2020 [43]. In 2003, the SARS-CoV virus pulled the world’s output down by $50 billion. The early estimation for the cost to the global economy as a result of the outbreak of COVID-19 is about $360 billion [44]. This is because China’s GDP shares were approximately 17% globally as of 2019, which was about four times higher than in 2003, and the confirmed infected cases (at the time of doing the economic estimation, i.e., at the beginning of February 2020) are more than 2 times larger than the total of SARS. Given that the number of infected cases (109,343 confirmed cases) is currently approximately 14 times larger than SARS cases [45], and that the death toll due to COVID-19 has surpassed that of the SARS epidemic, the economic impact of COVID-19 might be much larger than $360 billion.

Furthermore, in order to win the battle against this outbreak, information on the epidemiological characteristics, such as the identification of the animal reservoirs [46] (Figure 1) and the risk factor of the disease, is also essential. The intermediate host carrying the disease is important to identify not only for the current epidemic, but also to eliminate a future outbreak. Together with the all aforementioned factors, the race for a vaccination against COVID-19 is equally essential. Although at this stage there is no registered treatment or vaccine for COVID-19, Zhang has recently mentioned some potential interventions [47], such as nutritional interventions (Vitamin A, B, C, D, E, and other trace minerals such as zinc and iron). Due to the high percentage of identicality in the sequence (up to 82% of the genome structure) between SARS-COV-2 and the SARS-CoV virus, immuno-enhancers and other specific treatment that have been applied for SARS could also be considered [47] to use for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.N.; writing—original draft preparation, T.N.; manuscript revision, T.N, D.D.B., and A.W.; funding acquisition, D.D.B., A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, the CORONADX project, grant agreement No: 101003562, and the VIVALDI project, grant agreement No: 773422.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), Situation Report 11. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200131-sitrep-11-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=de7c0f7_4.

- 2.Novel Coronavirus ( 2019-nCoV ) Situation Report 48. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200308-sitrep-48-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=16f7ccef_4.

- 3.How 2019-nCoV Spreads. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/transmission.html.

- 4.Holshue M.L., DeBolt C., Lindquist S., Lofy K.H., Wiesman J., Bruce H., Spitters C., Ericson K., Wilkerson S., Tural A., et al. First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C., Zimmer T., Thiel V., Janke C., Guggemos W., et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phan L.T., Nguyen T.V., Luong Q.C., Nguyen T.V., Nguyen H.T., Le H.Q., Nguyen T.T., Cao T.M., Pham Q.D. Importation and Human-to-Human Transmission of a Novel Coronavirus in Vietnam. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:872–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO, Novel Coronavirus, Situation Dashboard. [(accessed on 9 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/

- 8.Cohen J., Kupferschmidt K. Strategies shift as coronavirus pandemic looms. Science. 2020;367:962–963. doi: 10.1126/science.367.6481.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Italy Announces Lockdown as Global Coronavirus Cases Surpass 105,000. [(accessed on 8 March 2020)]; Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/08/asia/coronavirus-covid-19-update-intl-hnk/index.html.

- 10.Wu J.T., Leung K., Leung G.M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: A modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395:689–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Update: ‘A Bit Chaotic.’ Christening of New Coronavirus and Its Disease Name Create Confusion. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/02/bit-chaotic-christening-new-coronavirus-and-its-disease-name-create-confusion.

- 12.Ji W., Wang W., Zhao X., Zai J., Li X. Homologous recombination within the spike glycoprotein of the newly identified coronavirus may boost cross-species transmission from snake to human. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cyranoski D. Did pangolins spread the China coronavirus to people? Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Recommendations to Reduce Risk of Transmission of Emerging Pathogens from Animals to Humans in Live Animal Markets. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus/who-recommendations-to-reduce-risk-of-transmission-of-emerging-pathogens-from-animals-to-humans-in-live-animal-markets.

- 15.Wang W., Tang J., Wei F. Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:441–447. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang B., Bragazzi N.L., Li Q., Tang S., Xiao Y., Wu J. An updated estimation of the risk of transmission of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCov) Infect. Dis. Model. 2020;5:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher T.M., Buchmeier M.J. Coronavirus Spike Proteins in Viral Entry and Pathogenesis. Virology. 2001;279:371–374. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoeman D., Fielding B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: Current knowledge. Virol. J. 2019;16:69. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gralinski L., Menachery V.D. Return of the Coronavirus: 2019-nCoV. Viruses. 2020;12:135. doi: 10.3390/v12020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen T., Andreasen S.Z., Wolff A., Bang D.D. From Lab on a Chip to Point of Care Devices: The Role of Open Source Microcontrollers. Micromachines. 2018;9:403. doi: 10.3390/mi9080403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ke C.-M., Tsai H.-C., Chen Y.-S., Huang Y.-H., Lai Y.-Y., Chen Y.-J., Ni Y.-Y., Li C.-H., Lee S.S.-J. Outbreak investigation of pandemic influenza A H1N1 at the emergency department in a medical center in Southern Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2015;48:S36. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2015.02.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isere E.E., Fatiregun A., Ajayi I.O. An overview of disease surveillance and notification system in Nigeria and the roles of clinicians in disease outbreak prevention and control. Niger. Med. J. 2015;56:161–168. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.160347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones G., Le Hello S., Silva N.J.-D., Vaillant V., De Valk H., Weill F.-X., Le Strat Y. The French human Salmonella surveillance system: Evaluation of timeliness of laboratory reporting and factors associated with delays, 2007 to 2011. Eurosurveillance. 2014;19:20664. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.1.20664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coronavirus Infection Tally on Diamond Princess hits 135 as Tests for All Passengers Eyed. [(accessed on 10 February 2020)]; Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/02/10/national/japan-test-all-passengers-diamond-princess-cruise-ship-coronavirus/#.XkQLz2hKhaQ.

- 26.Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K., Bleicker T., Brünink S., Schneider J., Schmidt M.L., et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25:2000045. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu D.K.W., Pan Y., Cheng S.M.S., Hui K.P.Y., Krishnan P., Liu Y., Ng D.Y.M., Wan C.K.C., Yang P., Wang Q., et al. Molecular Diagnosis of a Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Causing an Outbreak of Pneumonia. Clin. Chem. 2020;7:1–7. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruning A.H., Aatola H., Toivola H., Ikonen N., Savolainen-Kopra C., Blomqvist S., Pajkrt D., Wolthers K.C., Koskinen J.O. Rapid detection and monitoring of human coronavirus infections. New Microbes New Infect. 2018;24:52–55. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaunt E.R., Hardie A., Claas E.C.J., Simmonds P., Templeton K.E. Epidemiology and Clinical Presentations of the Four Human Coronaviruses 229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43 Detected over 3 Years Using a Novel Multiplex Real-Time PCR Method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:2940–2947. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00636-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho C.H., Lee C.K., Nam M.H., Yoon S.-Y., Lim C.S., Cho Y., Kim Y.K. Evaluation of the AdvanSure™ real-time RT-PCR compared with culture and Seeplex RV15 for simultaneous detection of respiratory viruses. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014;79:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.There’s Only One Way to Know If You Have the Coronavirus, and It Involves Machines Full of Spit and Mucus. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/how-to-know-if-you-have-the-coronavirus-pcr-test-2020-1?r=US&IR=T.

- 32.The US Fast-Tracked a Coronavirus Test to Speed Up Diagnoses. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/the-us-fast-tracked-a-coronavirus-test/

- 33.Assistance to Wuhan, High-level Mobile Biosafety Lab Departs. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: http://www.chinacdc.cn/yw_9324/202002/t20200204_212214.html.

- 34.New Emergency Detection Laboratory Run by BGI Starts Trial Operation in Wuhan, Designed to Test 10,000 Samples Daily. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.bgi.com/global/company/news/new-emergency-detection-laboratory-run-by-bgi-starts-trial-operation-in-wuhan-designed-to-test-10000-samples-daily/

- 35.Nagamine K., Hase T., Notomi T. Accelerated reaction by loop-mediated isothermal amplification using loop primers. Mol. Cell. Probes. 2002;16:223–229. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.2002.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Francois P., Tangomo M., Hibbs J., Bonetti E.-J., Boehme C.C., Notomi T., Perkins M.D., Schrenzel J. Robustness of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction for diagnostic applications. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2011;62:41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galvez L.C., Barbosa C.F.C., Koh R.B.L., Aquino V.M. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assays for the detection of abaca bunchy top virus and banana bunchy top virus in abaca. Crop. Prot. 2020;131:105101. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2020.105101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vivaldi Project, Technical University of Denmark. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: www.vivaldi-ia.eu.

- 39.COVID-19 IgM/IgG Rapid Test. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.biomedomics.com/products/infectious-disease/covid-19-rt/

- 40.Ahn S.J., Baek Y.H., Lloren K.K.S., Choi W.-S., Jeong J.H., Antigua K.J.C., Kwon H.-I., Park S.-J., Kim E.-H., Kim Y.-I., et al. Rapid and simple colorimetric detection of multiple influenza viruses infecting humans using a reverse transcriptional loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) diagnostic platform. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019;19:676. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4277-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeon S.B., Seo D.J., Oh H., Kingsley D., Choi C. Development of one-step reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification for norovirus detection in oysters. Food Control. 2017;73:1002–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X., Seo D.J., Lee M.H., Choi C., Onderdonk A.B. Comparison of Conventional PCR, Multiplex PCR, and Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assays for Rapid Detection of Arcobacter Species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;52:557–563. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02883-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.US$675 Million Needed for New Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Global Plan. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/05-02-2020-us-675-million-needed-for-new-coronavirus-preparedness-and-response-global-plan.

- 44.Economic Vulnerabilities to the Coronavirus: Top Countries at Risk. [(accessed on 13 March 2020)]; Available online: https://www.odi.org/blogs/16639-economic-vulnerabilities-coronavirus-top-countries-risk.

- 45.Wang C., Horby P.W., Hayden F.G., Gao G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L., Liu Y. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: A systematic review. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]