Abstract

Samples were taken at different levels of thermal maturity in the unconventional Bakken source rock. Programmed pyrolysis derived Tmax, solid bitumen reflectance, liptinite group maceral UV fluorescence, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy as different thermal maturity indicators were utilized in order to compare redox-sensitive trace metal (TM) concentration to maturity variations and disclose any probable relationship. Comparing redox-sensitive TMs with total organic carbon revealed the presence of anoxic/euxinic conditions in the depositional environment of the Bakken Shale. Although some of the TMs (V and Mo) exhibit slightly positive correlations with some of the thermal maturity indices used in this study, the correlations between other redox-sensitive TMs with maturity were neutral. Collectively, this study demonstrates that thermal maturity may have an impact on some redox-sensitive TMs such as Mo and V concentrations in marine sediments. Additional samples spanning higher maturities will need to be included because there is a possibility that an increase in thermal maturity may lead to the release and liberation of some redox-sensitive TMs from the organic matter (OM) directly. Remineralization and decomposition of OM with thermal maturity advance could release sulfur as a source of thermogenic H2S, which could accelerate pore water/rock interaction and authigenic Fe-sulfides. This could enhance the capability of uptaking of most of the redox-sensitive TMs and increase their concentration in pore water.

Introduction

The Bakken Formation in Williston Basin, as one of the most productive unconventional shale plays in North America, has a vast extension and has occupied large areas in parts of North Dakota, Montana, and the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba (Figure 1). The Late Devonian—Early Mississippian Bakken Formation consists of four members: two source rocks and two reservoir rocks.1−5 The black organic-rich shales in the upper and lower members represent the source rock while the carbonate-rich fine-grained sandstone and siltstone in the middle member along with the Pronghorn member are the reservoir rocks. It should be noted that the Pronghorn member appears sporadically in parts of the basin. The Bakken Formation reaches a maximum thickness of 150 ft (∼50 m) in the central part of the basin.1 This formation has no surface outcrop, and all of the studies on this formation are conducted by analyzing drill cuttings and core samples. The Bakken source rock is reported to be deposited under anoxic/euxinic conditions6−10 and in a relatively deep marine (>200 m) environment.11−14 Other studies15 indicate that the Bakken Formation was deposited in a stratified water column, which provided appropriate conditions for concentration and preservation of organic matter (OM).

Figure 1.

Location map of the study area in North Dakota portion of the Williston Basin and wells location.

The organic geochemistry of the Bakken source rock (upper and lower members) has been the subject of numerous studies.6,7,16−21 On the contrary, studies on the inorganic fraction of this source rock are limited. In this regard, the analysis of trace metals (TMs) in terms of their concentrations and distribution patterns can provide a better insight into the depositional environment conditions. This information enables us to better understand OM occurrence and its preservation, which provides a more meaningful interpretation of organic geochemistry studies.

Previous Studies

Chermak and Schreiber22 studied the relationship between trace elements/associated minerals from nine major shale plays in the United States (Antrim, Bakken, Barnett, Eagle Ford, Haynesville, Marcellus, New Albany, Utica, and Woodford shales) and related the results to the hydraulic fracturing performance. They argued that trace element/mineral concentration can be used to estimate the hydraulic fracturing ability of the rocks. Kocman23 studied elemental distribution patterns in the Bakken Formation using a handheld X-ray fluorescence (XRF) device and integrated this information with other conventional methods, such as petrographic studies, to develop a sequence stratigraphic framework for the Bakken. The above author reported a significant enrichment of molybdenum (Mo), uranium (U), and vanadium (V) TMs in the upper and lower members. Nandy et al.9 derived trace element concentrations in the Bakken source rock also using a handheld XRF device. A combination of such data with mineralogical assemblages, stable isotopes (carbon/oxygen/sulfur), and total organic carbon (TOC) enabled the above authors to reveal the effects of detrital sediment influx into the basin and hence the anoxic/euxinic conditions in productivity, preservation, and dilution of the OM in the Bakken source rock. They also reported enrichment of redox-sensitive TMs including Mo, V, U, nickel (Ni), and copper (Cu). Scott et al.24 studied the hyperenrichment of V and zinc (Zn) in the Bakken Formation and realized that high concentrations of V could be the result of very high levels of dissolved H2S in the basin bottom waters or sediments. The hyper enrichment of Zn was linked to the activity of a certain type of sulfide-oxidizing bacteria (phototrophic) and the development of photic-zone euxinia.

Although these limited studies have investigated the inorganic part of the Bakken source rock, the relationship between thermal maturity trends of the OM and these elements/metals remains unclear. To fill this knowledge gap, an attempt was made to discuss the plausible influence of thermal maturity on the distribution of redox-sensitive TMs, such as Mo, V, Zn, Cu, Ni, and chromium (Cr). In order to tackle this problem from different physicochemical perspectives, three different quantitative thermal maturity indicators, including programmed pyrolysis derived Tmax,25−27 solid bitumen reflectance,28−31 nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy,21 and also the liptinite macerals UV fluorescence color32 as a qualitative indicator, have been utilized. Both the upper and lower members are considered to have similar sedimentary facies and organic geochemistry characteristics and deposited under relatively deep marine (>200 m) and anoxic conditions.14,33−35 As a result, both members can be considered as a single organofacies when evaluating the relationship between thermal maturity and TM variations. Although the number of samples is limited (30 samples), considering the thickness of the shale members (6–24 and 7–51 ft, upper and lower members, respectively, Table 1), two samples taken from each member should reasonably represent the scope of this study, which is to explain the possible influence of thermal advance on TM concentrations. Readers should note that authors do not intend to present basinwide variations on TMs and are trying to set forth the idea that TM concentration may vary with maturity in different wells drilled in regions with varying thermal maturity. Nonetheless, the existence of all stages of thermal maturity, from immature to relatively late-mature in the Bakken, provided the opportunity to examine the effects of thermal maturity evolution on TM concentration. Although we recognize that a major portion of the samples used in this study are at the immature/early mature stages, which may impact statistical analysis somewhat due to the limited availability of peak and late mature samples, the authors believe that the current collection of samples could still provide preliminary ideas on the possible effects of thermal maturity and its progression on TM concentration in the Bakken Shale.

Table 1. Well IDs, the Bakken Formation, and the Upper and Lower Member Thickness.

| the Bakken Formation | the upper shale | the lower shale | |

|---|---|---|---|

| well IDa | thickness (ft) | thickness (ft) | thickness (ft) |

| 1 | 95 | 10 | 33 |

| 3 | 28 | 6 | 7 |

| 5 | 110 | 21 | 23 |

| 6 | 101 | 9 | 24 |

| 7 | 94 | 10 | 24 |

| 8 | 85 | 12 | 40 |

| 9 | 150 | 18 | 51 |

| 11 | 82 | 24 | 36 |

| 12 | 69 | 14 | 9 |

| 14 | 21 | 10 | 0 |

Well ID is not equivalent to well numbers.

Methods and Materials

Ten wells were selected across the North Dakota portion of the Williston Basin with a good areal distribution for sampling. Cores from these wells are stored at the Wilson M. Laird Core Library of the North Dakota Geological Survey located at the University of North Dakota campus. A total of thirty (30) samples from the lower and upper Bakken Shale members were selected to prepare whole-rock polished blocks (pellets). The polished blocks were prepared according to the ISO 7404-236 standard. Reflectance measurements were performed following the ASTM Standard D7708.37 Because of the scarcity/absence of vitrinite, reflectance measurements were made on solid bitumen particles, and their reflectance values are reported as SBRO % (solid bitumen reflectance percentage) (Table 2). The reflectance standards used included Sapphire and YAG (Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet) having RO of 0.47 and 0.97%, respectively. A LEICA DM 2500-P microscope equipped with J&M photometer TIDAS S MSP-200 was used for SBRO % and at least fifty (50) SBRO measurements per sample were acquired. Analysis under UV light (fluorescence) of liptinite group macerals was qualitative and complementary to reflectance. Fluorescence was performed using the following filters: excitation at 465 nm; combined beam splitter and barrier with a cut at 515 nm. The ICCP nomenclature, as described in Pickel et al.,38 was used to describe the liptinite group macerals in the Bakken Formation samples.

Table 2. Well IDs, Sample Depth, the Bakken Formation Members, TOC, Thermal Maturity Indices, and Elemental Analysis Results for Al, Mo, V, Zn, Cu, Ni, and Cra.

| well ID | depth (ft) | member (-) | TOC (wt %) | Tmax (°C) | maturity level (-) | SBRO (%) | NMR (mg H/g) | Al (ppm) | Mo (ppm) | V (ppm) | Zn (ppm) | Ni (ppm) | Cu (ppm) | Cr (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3774 | L. Bakken | 3.53 | 420 | immature | 0.38 | 3.50 | 51,010 | 68 | 15 | 38 | 38 | ||

| 3785 | L. Bakken | 14.93 | 410 | immature | 0.37 | 0.40 | 41,729 | 265 | 738 | 1405 | 385 | 60 | 110 | |

| 3 | 5996 | U. Bakken | 16.29 | 425 | immature | 0.47 | 5.00 | 48,292 | 77 | 2169 | 26 | 420 | 123 | |

| 5999 | U. Bakken | 7.33 | 426 | immature | 0.53 | 4.00 | 56,292 | 6 | 910 | 28 | 144 | 266 | ||

| 5 | 7337.5 | U. Bakken | 12.10 | 438 | early mature | 0.51 | 14.00 | 50,395 | 60 | 1037 | 19 | 277 | 112 | 82 |

| 7342.7 | U. Bakken | 10.86 | 437 | early mature | 0.51 | 13.00 | 20,529 | 143 | 466 | 1910 | 293 | 54 | 146 | |

| 7419 | L. Bakken | 17.13 | 435 | early mature | 0.52 | 42,947 | 308 | 774 | 118 | 388 | 64 | |||

| 7431.1 | L. Bakken | 13.06 | 435 | early mature | 0.52 | 8.70 | 50,366 | 216 | 242 | 20 | 266 | 75 | ||

| 6 | 7625.5 | U. Bakken | 17.82 | 436 | early mature | 0.47 | 8.50 | 47,501 | 250 | 1536 | 1511 | 460 | 102 | |

| 7631 | U. Bakken | 21.22 | 431 | immature | 0.43 | 10.37 | 35,737 | 373 | 1405 | 578 | 542 | 106 | 90 | |

| 7707.2 | L. Bakken | 14.65 | 437 | early mature | 0.44 | 46,339 | 286 | 830 | 246 | 370 | 64 | |||

| 7718.6 | L. Bakken | 14.01 | 435 | early mature | 0.43 | 10.80 | 53,674 | 246 | 250 | 23 | 290 | 71 | ||

| 7 | 8203.2 | U. Bakken | 18.07 | 431 | immature | 0.47 | 54,201 | 73 | 1013 | 18 | 264 | 105 | ||

| 8207.5 | U. Bakken | 20.98 | 425 | immature | 0.47 | 10.27 | 38,692 | 225 | 765 | 368 | 389 | 111 | ||

| 8279 | L. Bakken | 13.17 | 431 | immature | 0.44 | 9.51 | 40,046 | 308 | 868 | 107 | 316 | 47 | ||

| 8291.7 | L. Bakken | 14.61 | 431 | immature | 0.44 | 11.00 | 43,977 | 279 | 609 | 60 | 305 | 63 | ||

| 8 | 8987.5 | L. Bakken | 6.09 | 435 | early mature | 0.46 | 11.40 | 17,138 | 133 | 406 | 11 | 168 | 30 | 165 |

| 8995.5 | L. Bakken | 14.03 | 434 | immature | 0.50 | 9.20 | 33,847 | 238 | 532 | 321 | 262 | 51 | 120 | |

| 9 | 10,433 | U. Bakken | 11.92 | 448 | peak mature | 0.74 | 13.50 | 80,512 | 189 | 1475 | 450 | 84 | ||

| 10,527 | U. Bakken | 16.66 | 448 | peak mature | 0.83 | 62,515 | 1111 | 1460 | 246 | 470 | 123 | 177 | ||

| 10,541 | L. Bakken | 11.16 | 448 | peak mature | 0.81 | 43,538 | 286 | 386 | 68 | 441 | 153 | 90 | ||

| 10,547 | L. Bakken | 13.13 | 448 | peak mature | 0.74 | 58,160 | 288 | 64 | 683 | 125 | 82 | |||

| 11 | 11,159 | U. Bakken | 9.34 | 453 | late mature | 0.94 | 52,737 | 799 | 2554 | 2276 | 373 | 100 | 102 | |

| 11,162 | U. Bakken | 10.42 | 451 | late mature | 0.98 | 42,223 | 656 | 1074 | 475 | 332 | 83 | 124 | ||

| 12 | 9447.5 | U. Bakken | 12.66 | 426 | immature | 0.47 | 6.18 | 39,383 | 33 | 217 | 87 | 114 | 70 | 70 |

| 9453.5 | U. Bakken | 14.80 | 424 | immature | 0.42 | 9.00 | 37,674 | 325 | 686 | 28 | 315 | 48 | ||

| 9503.5 | L. Bakken | 17.32 | 425 | immature | 0.44 | 6.00 | 39,530 | 372 | 733 | 69 | 335 | 54 | ||

| 9507.1 | L. Bakken | 19.78 | 422 | immature | 0.25 | 6.00 | 49,270 | 384 | 868 | 1099 | 417 | 80 | 41 | |

| 14 | 9670.4 | U. Bakken | 11.11 | 429 | immature | 0.48 | 10.40 | 49,829 | 101 | 284 | 94 | 309 | 73 | |

| 9673.3 | U. Bakken | 6.99 | 428 | immature | 0.46 | 8.00 | 59,785 | 124 | 192 | 159 | 298 | 51 | 66 |

TOC, Tmax, and SBRO data are retrieved from Abarghani et al.35

All samples were analyzed utilizing the Basic/Bulk-Rock programmed pyrolysis method for source rocks by a commercial Rock-Eval 6 instrument (Vinci Technologies, France) to obtain TOC and Tmax. In this method, 15 or 60 mg of grounded bulk samples (based on the reactive kerogen richness39) was heated for 3 min isothermally, and then, the temperature was increased with a rate of 25 °C/min up to 650 °C, under inert gas atmosphere (nitrogen) in the pyrolysis oven. Pyrolysis was followed by oxidation to 850 °C under high-purity air. TOC content was obtained by summing the pyrolizable carbon (PC) and the residual carbon. For a detailed description of the programmed pyrolysis method, the reader is referred to Behar et al.40 NMR measurements were performed with a hydrogen special spectrometer at 22 MHz on sample chips weighing approximately 20 g. The interecho spacing time of less than 0.1 ms was selected to detect solid OM in the samples. The T1 and T2 data were acquired using an inversion recovery and CPMG sequence, respectively, to obtain T1–T2 2D maps.21 Finally, all samples were analyzed by utilizing a commercial XRF Supermini200 WDXRF by Rigaku for the trace and major elements utilizing the fundamental parameters method. In this method, XRF analysis can be carried out standardless because the elemental peak intensities are converted to elemental concentrations based on theoretical equations (detection limits of 21.7, 10.8, 3.5, 3.3, 3, 33.5, and 2.4 ppm for Al, V, Ni, Cu, Zn, Cr, and Mo, respectively). To perform XRF analysis, 10 g of the powdered sample was pelletized by mixing with 1 g of the paraffin binder (mixing ratio of 1:10) and then pressed by an automatic press machine with a maximum load of 300 kN to produce flat and cylindrical shaped disks.

Results

Trace Metals

To take into account differences in dilution by the detrital material, the TM concentrations have been normalized to Al41−44 (Table 3). Detrital influx could have a great impact on OM preservation and also authigenic mineral formation and concentration. Where there is a significant detrital influx into the basin, OM dilution can occur and, if it continues, it may lead to OM decay and decomposition. Detrital influx can also change the trends of authigenic mineral formation by changing the availability of elements and the depositional environment physical and chemical properties and conditions, such as pH, Eh, salinity, and suspended sediments. Aluminum is expected to get extracted from aluminosilicate phases entirely.42

Table 3. Al-Normalized Values for Redox-Sensitive Trace Metals.

| well | depth (ft) | Mo/Al × 10,000 | V/Al × 10,000 | Zn/Al × 10,000 | Ni/Al × 10,000 | Cu/Al × 10,000 | Cr/Al × 10,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3774 | 13.33 | 2.94 | 7.45 | 7.45 | ||

| 3785 | 63.50 | 176.86 | 336.70 | 92.26 | 14.38 | 26.36 | |

| 3 | 5996 | 15.94 | 449.14 | 5.38 | 86.97 | 25.47 | |

| 5999 | 1.07 | 161.66 | 4.97 | 25.58 | 47.25 | ||

| 5 | 7337.5 | 11.91 | 205.77 | 3.77 | 54.97 | 22.22 | 16.27 |

| 7342.7 | 69.66 | 227.00 | 930.39 | 142.72 | 26.30 | 71.12 | |

| 7419 | 71.72 | 180.22 | 27.48 | 90.34 | 14.90 | ||

| 7431.1 | 42.89 | 48.05 | 3.97 | 52.81 | 14.89 | ||

| 6 | 7625.5 | 52.63 | 323.36 | 318.10 | 96.84 | 21.47 | |

| 7631 | 104.37 | 393.15 | 161.74 | 151.66 | 29.66 | 25.18 | |

| 7707.2 | 61.72 | 179.11 | 53.09 | 79.85 | 13.81 | ||

| 7718.6 | 45.83 | 46.58 | 4.29 | 54.03 | 13.23 | ||

| 7 | 8203.2 | 13.47 | 186.90 | 3.32 | 48.71 | 19.37 | |

| 8207.5 | 58.15 | 197.72 | 95.11 | 100.54 | 28.69 | ||

| 8279 | 76.91 | 216.75 | 26.72 | 78.91 | 11.74 | ||

| 8291.7 | 63.44 | 138.48 | 13.64 | 69.35 | 14.33 | ||

| 8 | 8987.5 | 77.61 | 236.90 | 6.42 | 98.03 | 17.50 | 96.28 |

| 8995.5 | 70.32 | 157.18 | 94.84 | 77.41 | 15.07 | 35.45 | |

| 9 | 10,433 | 23.47 | 183.20 | 55.89 | 10.43 | ||

| 10,527 | 177.72 | 233.54 | 39.35 | 75.18 | 19.68 | 28.31 | |

| 10,541 | 65.69 | 88.66 | 15.62 | 101.29 | 35.14 | 20.67 | |

| 10,547 | 49.52 | 11.00 | 117.43 | 21.49 | 14.10 | ||

| 11 | 11,159 | 151.51 | 484.29 | 431.58 | 70.73 | 18.96 | 19.34 |

| 11,162 | 155.37 | 254.36 | 112.50 | 78.63 | 19.66 | 29.37 | |

| 12 | 9447.5 | 8.38 | 55.10 | 22.09 | 28.95 | 17.77 | 17.77 |

| 9453.5 | 86.27 | 182.09 | 7.43 | 83.61 | 12.74 | ||

| 9503.5 | 94.11 | 185.43 | 17.46 | 84.75 | 13.66 | ||

| 9507.1 | 77.94 | 176.17 | 223.06 | 84.64 | 16.24 | 8.32 | |

| 14 | 9670.4 | 20.27 | 56.99 | 18.86 | 62.01 | 14.65 | |

| 9673.3 | 20.74 | 32.12 | 26.60 | 49.85 | 8.53 | 11.04 |

The Bakken Shale samples exhibited a general enrichment pattern as V > Zn > Ni > Mo > Cr > Cu, which is slightly different from what was presented by Rimmer:45 Mo > Zn > V > Ni > Cu > Cr for redox-sensitive TM concentration in black shales. However, the concentrations of V and Zn are in agreement with previously reported values by Scott et al.24 for the Bakken Shale. The anoxic/euxinic conditions of the Bakken depositional environment have been reported in several studies.9,10,23,24 It is well known that anoxic/euxinic environments are suitable for OM concentration and preservation. In the next section, the relationship between each redox-sensitive element with TOC content and three different quantitative thermal maturity indices will be investigated. The liptinite macerals fluorescence color was used to confirm the programmed pyrolysis-derived Tmax results.

Thermal Maturity Evaluation

Various analytical methods are commonly used in thermal maturity evaluation such as the maximum yield temperature during programmed pyrolysis (Tmax),25,26,46 vitrinite reflectance,28 NMR spectroscopy,21 or qualitative methods such as the liptinite maceral UV fluorescence color.32 A combination of the above methods is required to define the boundaries of the different stages of thermal maturity and accurately evaluate the source rock because each method is based on a different operational theory that analyzes the OM from different perspectives.

Programmed Pyrolysis and Telalginite Fluorescence

Tmax is one of the most commonly used parameters for thermal maturity assessments. Nevertheless, Tmax values should be utilized with caution for maturity evaluation because multiple factors can affect the accuracy of Tmax values. For example, samples with low reactive kerogen (S2) content (less than 0.5 mg HC/g Rock) would result in non-Gaussian and broad peaks, thus resulting in unreliable Tmax values39,47 (Figure 2). However, the Bakken Shale has been reported to have high S2 values regardless of the maturity level (S2 ranged from 13.74 to 128.71 with an average value of 57.21 mg HC/g rock at VRO of 0.61–1.02%35). This is true even when the Bakken samples were extracted using organic solvents to remove possible contamination by oil-based mud. Tmax increased by only 1–2 °C (which is within the reproducibility error) as a result of solvent extraction. Thus, any reduction of Tmax due to contamination can also be excluded. In addition, the effect of bitumen migration on the possible reduction of Tmax can be neglected in the Bakken Shale due to the fact that this source rock generally contains in situ generated bitumen not migrated bitumen (migrabitumen).35In situ conversion of telalginite to early-forming bitumen is well-known.31 During this process, telalginite (parent maceral) is converted gradually into fluorescing bitumen without having to invoke hydrocarbon migration. The fluorescence intensity of the generated bitumen decreases with increased maturity. In addition to the TOC content of the samples, the type of the OM,47 mineral matrix in organic lean sediments,25,48 and sulfur content of the samples49,50 are other factors to consider while using Tmax as a thermal maturity indicator. For this reason, researchers have recommended that pyrolysis-derived maturity interpretations should be supported by other means of analysis, such as vitrinite reflectance or liptinite group maceral fluorescence.39,47 From Table 2, it can be found that Tmax values vary from 410 to 453 °C, which represents a wide range of maturity, from immature to late mature.51 This is confirmed by the fluorescence colors of the liptinite macerals, mainly marine telalginite (Figure 3A,D). Although the fluorescence color of telalginite depends on the type of algae (unicellular or colonial) and environment of deposition (marine or lacustrine) among others factors,52−54 their color under UV excitation was used, in a qualitative manner, to assess the level of maturity of the OM in this study. The telalginite colors vary from pale greenish (immature; pre oil-window stage) to golden-yellow (mature; early-middle oil window) to dull-yellow to light-brown (mature; peak oil window) to dark-brown (late mature; upper oil window).27,55−57 This is in good agreement with the maturity determined by reflectance.

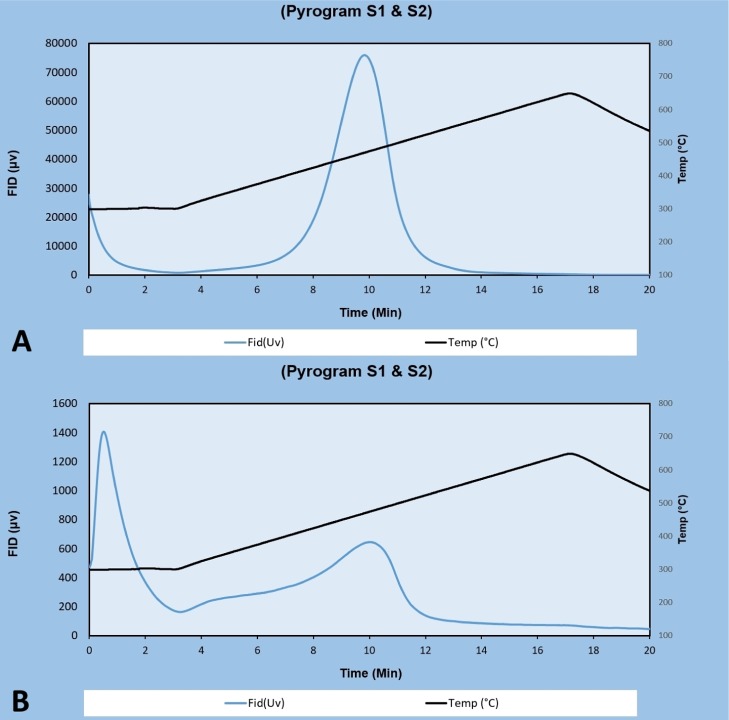

Figure 2.

Rock-Eval 6 pyrograms of Bakken Shale samples. (A) Well-formed narrow S2 peak without any “shoulder” (Well no. 12, depth 9453.5 ft). (B) Relatively poor-quality pyrolysis pyrogram showing a broad and skewed S2 peak and a low-temperature “shoulder” (S2 content of this sample is 0.38 mg HC/g Rock, well no. 8, depth 8932.5 ft). This sample was not included in this study.

Figure 3.

Liptinite group maceral fluorescence under the UV light along with the other thermal maturity indicators including programmed pyrolysis derived Tmax and equivalent vitrinite reflectance. (A) Pale greenish yellow fluorescence in a telalginite Tasmanites particle in an immature sample, depth 8291.7 ft. (B) Golden-yellow fluorescence in a telalginite particle in an early mature sample, depth 7707.2 ft. (C) Dull-yellow fluorescence in a bituminized telalginite particle that is at the peak of the oil window, depth 10,541 ft. (D) Orange to light brown fluorescence of bitumen derived from telalginite in the late mature stage, depth 11,159 ft. All photomicrographs were taken using a 50× oil immersion objective.

The TOC content in the studied Bakken samples varied from 3.53 to 21.22 wt %, with a mean value of 13.5 wt %. The bivariate plot (Figure 4) of each redox-sensitive TMs versus TOC (wt %) demonstrated that most samples, regardless of their maturity, plot in the anoxic/euxinic regions,44,58 in agreement with previous studies.9,10,24 Furthermore, almost all TMs positively correlate with the TOC content, most likely indicating that their concentrations are directly associated with OM content, and they could have been liberated from the rock matrix during thermal maturation. As conferred by Tribovillard et al.,58 Ni and Cu should exhibit a strong correlation with TOC variation based on their association with OM while they are later retained by iron sulfides. However, such a trend was not observed here in the Bakken samples in the anoxic zone possibly due to the statistically low number of samples. Entering the euxinic zone, an increasing trend in Ni and Cu concentration with TOC becomes prominent specifically in the immature samples, alike Mo and V. Additionally, it is suggested by Tribovillard et al.58 that V is mainly present in the authigenic mineral phases while Mo has stronger links to the sulfur-rich kerogen and pyrite. Plotting the redox-sensitive TMs from all samples versus Tmax (Figure 5) showed that the TM concentrations in all samples exhibit no meaningful trend with Tmax. To be more specific, while Mo, V, and Ni (Figure 5C,A,D) exhibited slightly positive correlations, other TMs including Cr, Cu, and Zn showed neutral correlations (Figure 5F,B,E). Calculating other important statistical parameter (P-value) for evaluating the degree of correlation also confirms the lack of any relationship for all of the studied TMs except for Mo and V where the R2 values are low but the P values are significant (0.02 and 0.14 for Mo and V, respectively). This low amounts of P value for the mentioned TMs demonstrate the rejection of the null hypothesis, and therefore it should be a relationship between these two TM concentration and Tmax. In some samples (particularly those at peak maturity), different concentrations of TMs were measured even though the samples had the same Tmax (Figure 5). This is inferred as either due to the original concentration of the TMs in those samples during deposition or statistical uncertainties.

Figure 4.

Redox-sensitive TM distribution vs TOC in four different stages of thermal maturity (A–F). All TMs concentrations are Al-normalized (×10–4). Most samples are in the anoxic/euxinic regions. Anoxic and euxinic thresholds extracted from Algeo and Maynard.44

Figure 5.

TMs enrichment patterns vs Tmax in four different stages of thermal maturity (A–F). All TMs concentrations are Al-normalized (×10–4).

Solid Bitumen Reflectance

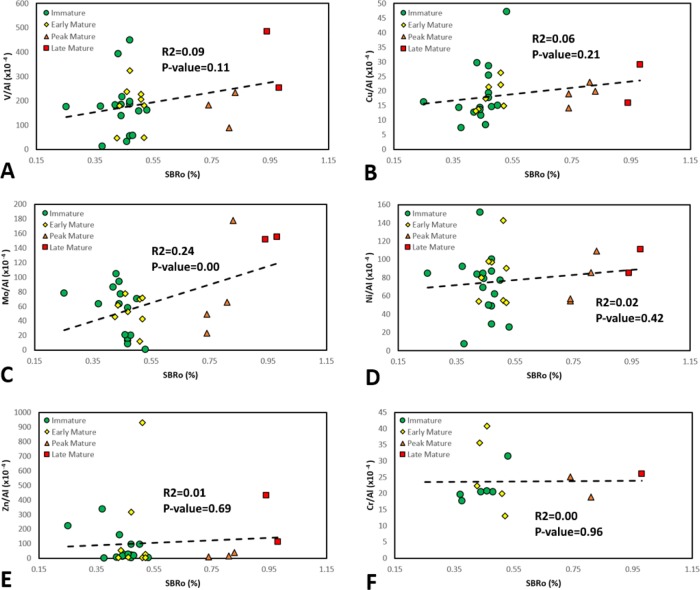

Vitrinite reflectance as a major maturity parameter28,59,60 can establish one of the most accurate thermal maturity information for source rock evaluation. However, a major drawback of this method is referred to as vitrinite scarcity or absence in pre-Devonian source rocks and also in marine sedimentary rocks. A significant number of studies28−31,61−63 indicate that it is reasonable to use solid bitumen reflectance when vitrinite is absent because vitrinite and solid bitumen follow similar maturation pathways with increasing thermal maturity.27 In the scarcity/absence of the vitrinite in the Bakken Shale samples, solid bitumen (Figure 6A,B) was used as the third thermal maturity indicator. It can be seen from Figure 6C that there is a reasonably good agreement between SBRO % and Tmax values. However, considering SBRO % versus TM concentration, no considerable relationship was observed between studied TMs with SBRO % increase except for Mo and V where the P values are significant (0.00 and 0.11 for Mo and V, respectively). Here, while some TMs, such as Mo and V, exhibited slightly positive relationships with thermal maturity (Figure 7A,C), others like Cu and Ni (Figure 7B,D) did not. Ultimately, Zn and Cr (Figure 7E,F) did not display any meaningful relationship with SBRO %.

Figure 6.

Solid bitumen reflectance was used as the third thermal maturity indicator in the scarcity/absence of vitrinite maceral. Photomicrographs of the Bakken solid bitumen samples. (A) Solid bitumen particle with intermediate reflectance (BRO,ran = 0.65%), well #6, depth 7631 ft. (B) Elongated grain of solid bitumen (BRO,ran = 0.35%), well #14 depth 9673.3 ft. Both photomicrographs were taken using a 50× oil immersion objective. (C) There is a good agreement between SB-derived RO and Tmax.

Figure 7.

TMs enrichment patterns vs SBRO % in four different stages of thermal maturity (A–F). All TMs concentrations are Al-normalized (×10–4).

NMR Spectroscopy

The complexity of shale plays in terms of constituent components has led to a growing need to employ new analytical methods for better understanding of OM conversion to hydrocarbon and related processes. NMR has recently gained attention and acceptance in the analysis of unconventional shale plays. In an NMR experiment, the longitudinal (T1) and the transverse relaxation times (T2) are measured.64−67T1 is the decay constant for the recovery of the z component of the nuclear spin magnetization (Mz), toward its thermal equilibrium value (Mz,eq). T2 is the decay constant for the component of M perpendicular to a magnetic field (B0) designated Mxy, MT, or M⊥. In general, the following equations (eqs 1–4) explain how T1 and T2 can be obtained through inversion

| 1 |

For instance, initial xy magnetization at time zero will decay to zero as

| 2 |

The resulting relaxation time distribution can be correlated with the distribution of pore sizes.68,69 When low-viscous fluids filled the void spaces in a porous material, the effect on the measured T2 is defined as follows70

| 3 |

where S is the pore surface area, ρ2 is the surface relaxivity of the pore surface for T2, V is the volume of the pores, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, D is the diffusion coefficient of the fluid, G is the magnetic field gradient, and TE is the echo spacing.69 The T1 response for low viscous fluids in porous materials is similar, though unaffected by the presence of internal gradients

| 4 |

where ρ1 is the surface relaxivity of the pore surface for T1. High-frequency NMR compared to low frequency provides a better signal-to-noise ratio in a rapid acquisition, which makes it an ideal tool to detect and distinguish signals from all sources of hydrogen nuclei in bulk samples (including water, hydrocarbon, solid OM, and hydroxyl) that can be separated based on their location on the NMR T1–T2 map71 (Figure 8A). Khatibi et al.21 utilized the amplitude of hydrogen in each zone and proposed that NMR signals can be used as maturity indicators. They explained that because NMR can detect different sources of hydrogen population in the samples, the OM zone (2) on the T1–T2 map could be considered as a new maturity index. Considering the fact that hydrogen content of OM decreases with thermal maturity, a relationship between maturity and hydrogen content in Region 2 (as a hydrogen indicator of OM) could become an additional analytical tool for source-rock evaluation in terms of thermal maturity.

Figure 8.

(A) T1–T2 map of a sample from well # 7, depth 8279 ft; regions (1) to (4) correspond to hydroxyl/bound water, solid OM, hydrocarbon in organic pores, and liquid hydrocarbon in porous media, respectively. (B) There is a good correlation between NMR spectroscopy derived thermal maturity and Tmax.

Based on the method proposed by Khatibi et al.,21 the NMR signal amplitude from Region 2 (OM) was plotted versus Tmax of all samples and showed a reasonably good correlation (Figure 8B). Therefore, the NMR signal amplitude can also be used as a thermal maturity indicator in this study. Cross-plotting redox-sensitive TMs versus NMR signal amplitudes denoted that although this new thermal maturity index and Tmax correlate well, there are still few discrepancies when compared to other thermal maturity plots. Based on bivariate plots, it can be seen that Ni (Figure 9D) exhibited a weak correlation with NMR signal amplitude compared to the other TMs (low P-value of 0.19). All other TMs, including V, Cu, Mo, Zn, and Cr (Figure 9), did not show any particular correlation with thermal maturity (low R2 and high P values). Generally, results showed less sensitivity of NMR spectroscopy to TM concentrations compared to Tmax or solid bitumen reflectance.

Figure 9.

TMs enrichment patterns vs NMR signal amplitude in three different stages of thermal maturity (A–F). All TMs concentrations are Al-normalized (×10–4).

Discussion

Among all TMs investigated in this study, Mo and V displayed slightly positive correlations with major thermal maturity indicators, such as Tmax and SBRO. As discussed by Algeo and Maynard,44 sulfur-reducing bacteria activities could release Mo from OM into connate waters in anoxic/euxinic environments. They also claimed that free H2S in the water column could possibly accelerate the authigenic sulfide-forming compounds and increase the diffusion of Mo. The Bakken Shale is rich in pyrite (FeS2), which could be the source of sulfur for H2S based on certain geochemical reactions.72 However, Gaspar et al.73 argued that such reactions could not have taken place in the Bakken Shale because reservoir conditions were not thermodynamically appropriate for pyrite oxidation.74 Gaspar et al.73 performed a detailed study on the produced waters from the Bakken in order to determine whether the source of H2S in the Bakken was biogenic or thermogenic. They concluded that H2S cannot have a biogenic source because measurable DNA from any microorganism was not found in the samples. Thus, they proposed a thermogenic source for the H2S based on sulfur isotope analysis, where the δ34S concentration of 10‰ and higher was considered thermogenic, and values between 0 and 10‰ reflect both biogenic/thermogenic generation origin for H2S.73,75 Thermal maturity not only will increase the thermogenic H2S level but also could speed up the process by releasing more sulfur from the OM (especially kerogen type II-S) through conversion to petroleum and other byproducts. As a result, the diffusion and concentration of Mo in the pore water in the shale matrix will increase.

Conversion of OM to petroleum and its byproducts through an increase in thermal maturation can lead to high levels of dissolved H2S (∼10 mM) in the bottom or pore water, as proposed by Scott et al.,24 which has caused hyperenrichment of V in the Bakken Shale. Algeo and Maynard44 have also addressed the effect of H2S on the concentration of V. They argued that under excessive reducing conditions, V could be taken by geoporphyrines or directly deposited as vanadium oxides in the presence of free H2S.44,76,77 Considering the significant recorded production of H2S in the Bakken, one possible explanation is that thermal progression may increase concentration of Mo and V through generation of H2S by liberating sulfur from the OM. Mossman and Nagy78 described the Athabasca tar sands where solid bitumen contains high amounts of Ni and V. Because solid bitumen is the most frequent OM in the Bakken Shales, one can explain the relative increase of V with thermal maturation as a result of gradual degradation of solid bitumen during the thermal advance and liberation of Vanadium.

Remaining TMs including Cu, Ni, Zn, and Cr did not correlate well with thermal maturity indicators. Scott et al.24 proposed a biogeochemical source for the hyperconcentration of Zn through sulfide-oxidizing bacteria by comparing the Bakken Shale with a modern era Framvaren Fjord (Norway) depositional environment. This can explain the initial origin of the concentration of Zn in sediments but fails to explicate the possible Zn enrichment with thermal maturity, considering the observations made by Gaspar et al.73 In another study, sulfide mineralization as a consequence of thermochemical sulfate reduction due to the interaction between basinal brines and hydrocarbons was reported as another pathways for Pb–Zn concentration from the world-class sandstone-hosted ore deposit of Pb–Zn at Laisvall where Pb is initially originated from bitumen in the Alum Shale Formation.79

It is discussed that Zn could be released from the OM through the activity of sulfate-reducing bacteria.44 Furthermore, as a result of OM decomposition, Zn could have been released to pore water.58 Zinc could be absorbed later by authigenic Fe-sulfides during the burial of sediments. Thermal maturity may increase the enrichment of Zn through the formation of more authigenic Fe-sulfides that can absorb the released Zn from the OM. However, the results from this study suggest that there is no correlation between Zn concentration with thermal maturity increase.

Similar processes were proposed for sulfate-reducing bacteria and also for the role of Fe-sulfides in uptaking the liberated Cu in solid solution.44,80−82 In the presence of sulfur under the euxinic conditions, Cu could directly be precipitated as CuS or Cu2S.44 Ni also could be precipitated as NiS under euxinic conditions or be absorbed by authigenic pyrite.44,80 Cr also could get liberated by remineralization of the OM during thermal maturity advance because it has been reported that Cr is commonly associated with OM in modern environments.44,83 Because of incompatibilities (structural/electronic) of Cr with pyrite crystals, the role of uptaking by authigenic Fe-sulfides and enrichment of Cr is assumed to be very limited.44,80,82

Most researchers have considered epigenetic sources, such as volcanic/hydrothermal activities or interaction with basinal brines during the geological time, to explain TM enrichment.42,84 Based on the above discussion, thermal maturity could play a possible role in OM remineralization/decomposition through the conversion of the OM into petroleum and other byproducts. During this process, some elements (including sulfur) are released and liberated into the pore water, which could generate free H2S and accelerate the above mentioned chemical reactions and cause the enrichment of TMs in the sediments by direct precipitation of sulfide compounds or uptaking in the form of Fe-sulfides. Consequently, the content of organic sulfur would decrease in the residual OM. The decrease in total sulfur content in the kerogen structure with an increase in thermal maturity has been discussed by Kelemen et al.85 based on X-ray photon spectroscopy analysis of the Devonian Duvernay Shale in Western Canada and also for an Asian located proprietary source rock. It should be noted that organic sulfur in aliphatic and aromatic compounds is found in all types of kerogen.85

In this study, a combination of four different methods (three quantitative and one qualitative) was employed to better illuminate thermal maturity interpretation. Any of the above maturity indicators, including pyrolysis-derived Tmax, the fluorescence color of telalginite, solid bitumen reflectance, and, finally, NMR spectroscopy is sensitive to specific characteristics of the OM but to a different degree. For instance, while Tmax or NMR spectroscopy considers chemical properties, solid bitumen reflectance represents physicochemical changes that occur within the OM structure with maturation. Therefore, a combination of all available thermal maturity indicators can lead to a more dependable interpretation of the OM chemical and physical maturity state.

The results of this study showed that Tmax exhibits a slightly positive correlation with the enrichment of some TMs such as V and Mo compared to other thermal maturity indicators. As mentioned earlier, Tmax is a direct function of petroleum generation/expulsion and could support the idea that TM enrichment will increase with OM conversion to petroleum in source rocks. The conversion also increases OM aromaticity and generates a more ordered macromolecule.86,87 However, there exist few samples in the data with similar Tmax values and different TM concentration levels (Figure 5). This is interpreted as either due to analytical error in the experiments or lack of chemical relevance in the above thermal maturity index with the TM concentration.

Although there was a good agreement between Tmax and thermal maturity derived from SBRO % and NMR spectroscopy, relatively different trends between these two maturity indices and NMR spectroscopy in particular with TM enrichment were observed. Utilizing solid bitumen reflectance as an indicator of thermal maturity should be done with care due to the existence of different population/generation of solid bitumen with various reflectance properties in the source rocks31,61,63. Furthermore, even within a single solid bitumen particle, variations in morphology, texture, and the degree of anisotropy is reported.31,63,88 Considering these effects, selection of the most appropriate population of solid bitumen could result in a more accurate thermal maturity interpretation. In this study, the reflectance of the solid bitumen population selected was in a good agreement with Tmax; hence a similar TM slight enrichment for Mo and V with increased thermal maturity was attained. Additionally, NMR spectroscopy as a proposed new indicator of thermal maturity21 was also utilized to examine the applicability of this method to investigate TM enrichment. However, the general trend of the TM concentration patterns did not depict any meaningful relationships with the NMR signals. This might be due to the NMR sensitivity toward magnetic and iron-bearing minerals, such as pyrite (which is abundant in the Bakken Shale) and ilmenite, which can affect the relaxation times and cause overlapping boundaries of different hydrogen populations in the T1–T2 maps. Therefore, it would be beneficial to employ a combination of all possible thermal maturity methods to better understand the effect of thermal maturity advance in the TM enrichment pattern.

The outcome of this study suggests a possible role of thermal maturity in the enrichment of few TMs such as Mo and V following sedimentation and during burial. However, in most cases, the correlation observed between the thermal maturity indicators used in this study and TMs was weak, especially with NMR spectroscopy. The overall results of this study point to the possibility that thermal maturity could have a possible impact on TM concentration, but further studies are necessary. In order to obtain more conclusive results, the authors suggest the use of extensive data covering a wider range of maturities and geologic formations of different ages.

Conclusions

Three different quantitative thermal maturity indices including programmed pyrolysis derived Tmax, solid bitumen reflectance, and NMR spectroscopy and also liptinite group maceral UV fluorescence as qualitative index were combined in order to study the probable effects of maturity variation on the concentration of redox-sensitive TMs. The UV fluorescence color of marine telalginite was used to confirm the Tmax-derived maturity levels. Comparing TM concentration with TOC contents indicated the presence of anoxic/euxinic conditions in the depositional environment of the Bakken Shale. The concentration of some of TMs (V and Mo) versus a number of direct indicators of thermal maturity (e.g., solid bitumen reflectance and Tmax) was found to be slightly positive compared to indirect maturity indices (e.g., NMR signal amplitude). In this regard, Mo and V concentration variations exhibited a better relationship with maturity indices (significant low P values) compared to Cu, Zn, and Cr.

The outcome of this study inferred that thermal maturity might play a possible role in redox-sensitive TM concentration in source rocks. With the increase in maturity and generation of hydrocarbons from OM, some TMs could be released and liberated from the OM structure directly and enter the connate water. Furthermore, releasing sulfur from the OM with thermal maturity could provide sulfur as a source of thermogenic H2S, which would accelerate the chemical reactions necessary for the additional concentration of TMs or form authigenic Fe sulfides later as a result of the capability of uptaking most of the TMs and increasing their concentration in the pore water.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank North Dakota Geological Survey, Core Library, for giving us access to the Bakken core samples, particularly Jeffrey Bader, geologist and director, as well as Kent Hollands, lab technician. The authors would also like to express their appreciation to Dr. Humberto Carvajal-Ortiz and Dr. Harry Xie from Core Laboratories in Houston, TX, for providing the geochemistry and NMR data. Two anonymous reviewers are sincerely thanked for constructive comments and reviews, which highly improved the quality of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Lefever J. A.; Martiniuk C. D.; Dancsok E. F. R.; Mahnic P. A.. Petroleum potential of the middle member, Bakken Formation, Williston Basin. Williston Basin Symposium, 1991; pp 74–94.

- LeFever J. A.Isopach of the Bakken Formation. North Dakota Geological Survey, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bottjer R. J.; Sterling R.; Grau A.; Dea P.. Stratigraphic Relationships and Reservoir Quality at the Three Forks–Bakken Unconformity, Williston Basin, North Dakota. Bakken-Three Forks Petroleum System in the Williston Basin; Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. L.Pronghorn member of the Bakken Formation, Williston Basin, USA: lithology, stratigraphy, reservoir properties. MS (Masters) Thesis, Colorado School of Mines, Arthur Lakes Library, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Theloy C.; Leonard J. E.; Smith S. C. An uncertainty approach to estimate recoverable reserves from the Bakken petroleum system in the North Dakota part of the Williston Basin. AAPG Bull. 2019, 103, 2295–2315. 10.1306/1208171621417181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster R. L. Petroleum Source Rocks and Stratigraphy of Bakken Formation in North Dakota: ABSTRACT. AAPG Bull. 1984, 68, 953. 10.1306/ad46166f-16f7-11d7-8645000102c1865d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner F. F.Petroleum geology of the Bakken Formation Williston Basin, North Dakota and Montana. Petroleum Geochemistry and Basin Evaluation; American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. G.; Bustin R. M. Lithofacies and paleoenvironments of the upper Devonian and lower Mississippian Bakken Formation, Williston Basin. Bull. Can. Pet. Geol. 1996, 44, 495–507. [Google Scholar]

- Nandy D.; Sonnenberg S. A.; Humphrey J. D. Factors Controlling Organic-richness in Upper and Lower Bakken Shale, Williston Basin: An Application Inorganic Geochemistry, presented at AAPG Annual Convention & Exhibition. Chem. Geol. 2015, 232, 12–32. [Google Scholar]

- Abarghani A.; Ostadhassan M.; Gentzis T.; Carvajal-Ortiz H.; Bubach B. Organofacies study of the Bakken source rock in North Dakota, USA, based on organic petrology and geochemistry. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 188, 79–93. 10.1016/j.coal.2018.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes M. D.; Holland F. D. Jr. Conodonts of the Bakken Formation (Devonian and Mississippian), Williston Basin, North Dakota. AAPG Bull. 1983, 67, 1341. [Google Scholar]

- Holland F. D. Jr.; Hayes M. D.; Thrasher L. C.; Huber T. P.. Summary of the biostratigraphy of the Bakken Formation (Devonian and Mississippian) in the Williston basin, North Dakota, 1987. Williston Basin Symposium, 1987.

- Egenhoff S.; Fishman N.. Stormy times in “anoxic” basins–tempestites in the Upper Devonian-Lower Mississippian Bakken Formation of North Dakota and implications for source rock depositional models (Abstract). AAPG Annual Convention and Exhibition, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2010; Vol. 67.

- Steptoe A.Petrofacies and depositional systems of the Bakken Formation in the Williston Basin, North Dakota. M.Sc. Thesis, West Virginia University, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lineback J. A.; Davidson M. L.. The Williston Basin-sediment-starved during the Early Mississippian, 1982. Williston Basin Symposium, 1982.

- Schmoker J. W.; Hester T. C. Organic carbon in Bakken formation, United States portion of Williston basin. AAPG Bull. 1983, 67, 2165–2174. 10.1306/AD460931-16F7-11D7-8645000102C1865D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg S. A.; Pramudito A. Petroleum geology of the giant Elm Coulee field, Williston Basin. AAPG Bull. 2009, 93, 1127–1153. 10.1306/05280909006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H.; Sonnenberg S. A.. Characterization for source rock potential of the Bakken Shales in the Williston Basin, North Dakota and Montana, 2013. Unconventional Resources Technology Conference; Society of Exploration Geophysicists, American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 2013; pp 117–126.

- Gentzis T.; Carvajal-Ortiz H.; Tahoun S.; Li C.; Ostadhassan M.; Xie H.; Mendonςa Filho J. G.. A multi-component approach to study the source-rock potential of the Bakken Shale in North Dakota, USA, using organic petrology, Rock-Eval pyrolysis, palynofacies, LmPy-GCMSMS geochemistry, and NMR spectroscopy. 34th Annual Meeting of the Society of Organic Petrology, 2017.

- Khatibi S.; Ostadhassan M.; Tuschel D.; Gentzis T.; Bubach B.; Carvajal-Ortiz H. Raman spectroscopy to study thermal maturity and elastic modulus of kerogen. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018a, 185, 103–118. 10.1016/j.coal.2017.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khatibi S.; Ostadhassan M.; Xie Z. H.; Gentzis T.; Bubach B.; Gan Z.; Carvajal-Ortiz H. NMR relaxometry a new approach to detect geochemical properties of organic matter in tight shales. Fuel 2019, 235, 167–177. 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.07.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chermak J. A.; Schreiber M. E. Mineralogy and trace element geochemistry of gas shales in the United States: Environmental implications. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2014, 126, 32–44. 10.1016/j.coal.2013.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kocman K. B.Interpreting depositional and diagenetic trends in the Bakken Formation based on handheld x-ray fluorescence analysis, Mclean, Dunn and Mountrail counties, North Dakota. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado School of Mines, Arthur Lakes Library, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scott C.; Slack J. F.; Kelley K. D. The hyper-enrichment of V and Zn in black shales of the Late Devonian-Early Mississippian Bakken Formation (USA). Chem. Geol. 2017, 452, 24–33. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2017.01.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espitalie J.; Deroo G.; Marquis F. La pyrolyse Rock-Eval et ses applications. Rev. Inst. Fr. Pet. 1985, 40, 563–579. 10.2516/ogst:1985035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lafargue E.; Marquis F.; Pillot D. Rock-Eval 6 applications in hydrocarbon exploration, production, and soil contamination studies. Rev. Inst. Fr. Pet. 1998, 53, 421–437. 10.2516/ogst:1998036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dembicki H.Practical Petroleum Geochemistry for Exploration and Production; Elsevier, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay P. K.Vitrinite Reflectance as Maturity Parameter: Petrographic and Molecular Characterization and its Applications to Basin Modeling; ACS Publications, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenherr J.; Littke R.; Urai J. L.; Kukla P. A.; Rawahi Z. Polyphase thermal evolution in the Infra-Cambrian Ara Group (South Oman Salt Basin) as deduced by maturity of solid reservoir bitumen. Org. Geochem. 2007, 38, 1293–1318. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2007.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen S. R.; Walters C. C.; Kwiatek P. J.; Freund H.; Afeworki M.; Sansone M.; Lamberti W. A.; Pottorf R. J.; Machel H. G.; Peters K. E.; Bolin T. Characterization of solid bitumens originating from thermal chemical alteration and thermochemical sulfate reduction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 5305–5332. 10.1016/j.gca.2010.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mastalerz M.; Drobniak A.; Stankiewicz A. B. Origin, properties, and implications of solid bitumen in source-rock reservoirs: a review. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 195, 14–36. 10.1016/j.coal.2018.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G. H.; Teichmüller M.; Davis A.; Diesel C. F. K.; Littke R.; Robert P.. Organic Petrology; Gebrüder Borntraeger: Berlin, 1998; pp 1–704. [Google Scholar]

- Angulo S.; Buatois L. A. Integrating depositional models, ichnology, and sequence stratigraphy in reservoir characterization: The middle member of the Devonian–Carboniferous Bakken Formation of subsurface southeastern Saskatchewan revisited. AAPG Bull. 2012, 96, 1017–1043. 10.1306/11021111045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Buatois L. A. Sedimentary facies and depositional environments of the Upper Devonian–Lower Mississippian Bakken Formation in eastern Saskatchewan. Summ. Invest. 2014, 1, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Abarghani A.; Ostadhassan M.; Gentzis T.; Carvajal-Ortiz H.; Ocubalidet S.; Bubach B.; Mann M.; Hou X. Correlating Rock-EvalTM Tmax with bitumen reflectance from organic petrology in the Bakken Formation. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2019, 205, 87–104. 10.1016/j.coal.2019.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ISO . Methods for the Petrographic Analysis of Coals Part 2: Methods of Preparing Coal Sample; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM . Standard Test Method for Microscopical Determination of the Reflectance of Vitrinite Dispersed in Sedimentary Rocks; ASTM International, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pickel W.; Kus J.; Flores D.; Kalaitzidis S.; Christanis K.; Cardott B. J.; Misz-Kennan M.; Rodrigues S.; Hentschel A.; Hamor-Vido M.; Crosdale P.; Wagner N. Classification of liptinite–ICCP System 1994. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2017, 169, 40–61. 10.1016/j.coal.2016.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal-Ortiz H.; Gentzis T. Critical considerations when assessing hydrocarbon plays using Rock-Eval pyrolysis and organic petrology data: Data quality revisited. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2015, 152, 113–122. 10.1016/j.coal.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behar F.; Beaumont V.; De B. Penteado H. L. Rock-Eval 6 technology: performances and developments. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. 2001, 56, 111–134. 10.2516/ogst:2001013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur M. A.; Brumsack H. J.; Jenkyns H. C.; Schlanger S. O.. Stratigraphy, geochemistry, and paleoceanography of organic carbon-rich Cretaceous sequences. Cretaceous Resources, Events and Rhythms; Springer, 1990; pp 75–119. [Google Scholar]

- Calvert S. E.; Pedersen T. F. Geochemistry of recent oxic and anoxic marine sediments: implications for the geological record. Mar. Geol. 1993, 113, 67–88. 10.1016/0025-3227(93)90150-t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morford J. L.; Russell A. D.; Emerson S. Trace metal evidence for changes in the redox environment associated with the transition from terrigenous clay to diatomaceous sediment, Saanich Inlet, BC. Mar. Geol. 2001, 174, 355–369. 10.1016/s0025-3227(00)00160-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Algeo T. J.; Maynard J. B. Trace-element behavior and redox facies in core shales of Upper Pennsylvanian Kansas-type cyclothems. Chem. Geol. 2004, 206, 289–318. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2003.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer S. M. Geochemical paleoredox indicators in Devonian–Mississippian black shales, central Appalachian Basin (USA). Chem. Geol. 2004, 206, 373–391. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2003.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters K. E.; Moldowan J. M.; Walters C. C.. The Biomarker Guide: Biomarkers in the Environment and Human History [V1]; Cambridge University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Peters K. E. Guidelines for evaluating petroleum source rock using programmed pyrolysis. AAPG Bull. 1986, 70, 318–329. 10.1306/94885688-1704-11d7-8645000102c1865d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sari A.; Vosoughİ Moradİ A.; Kulaksiz Y.; KÜBra YurtoĞLu A. Evaluation of the hydrocarbon potential, mineral matrix effect and gas oil ratio potential of oil shale from Kabalar Formation, Göynüuk, Turkey. Oil Shale 2015, 32, 25. 10.3176/oil.2015.1.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orr W. L. Kerogen/asphaltene/sulfur relationships in sulfur-rich Monterey oils. Org. Geochem. 1986, 10, 499–516. 10.1016/0146-6380(86)90049-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin T. B.; Birdwell J. E.; Lewan M. D.; Hill R. J.; Grayson M. B.; Mitra-Kirtley S.; Bake K. D.; Craddock P. R.; Abdallah W.; Pomerantz A. E. Sulfur species in source rock bitumen before and after hydrous pyrolysis determined by X-ray absorption near-edge structure. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 6264–6270. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.6b00744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters K. E.; Cassa M. R.. Applied source rock geochemistry: Chapter 5: Part II. Essential elements. The Petroleum System: From Source to Trap; American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stasiuk L. D. Fluorescence properties of Palaeozoic oil-prone alginite in relation to hydrocarbon generation, Williston Basin, Saskatchewan, Canada. Mar. Pet. Geol. 1994, 11, 219–231. 10.1016/0264-8172(94)90098-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo C. V.; Borrego A. G.; Cardott B.; das Chagas R. B. A.; Flores D.; Gonçalves P.; Hackley P. C.; Hower J. C.; Kern M. L.; Kus J.; Mastalerz M.; Mendonça Filho J. G.; de Oliveira Mendonça J.; Menezes T. R.; Newman J.; Suarez-Ruiz I.; da Silva F. S.; de Souza I. V. Petrographic maturity parameters of a Devonian shale maturation series, Appalachian Basin, USA. ICCP Thermal Indices Working Group interlaboratory exercise. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2014, 130, 89–101. 10.1016/j.coal.2014.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca C.; Mendonça J. O.; Mendonça Filho J. G.; Lézin C.; Duarte L. V. Thermal maturity assessment study of the late Pliensbachian-early Toarcian organic-rich sediments in southern France: Grands Causses, Quercy and Pyrenean basins. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2018, 91, 338–349. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann H. Spectral fluorometric analysis of extracts a new method for the determination of the degree of maturity of organic matter in sedimentary rocks. Bull. Cent. Rech. Explor.-Prod. Elf-Aquitaine 1981, 5, 635. [Google Scholar]

- Stach E.; Mackowsky M. T.; Teichmuller M.; Taylor G. H.; Chandra D.; Teichmuller R.. Stach’s Textbook of Coal Petrology; Gebruder Borntraeger: Berlin, 1982; p 535. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Rizer C. L.; Woods R. A. Microspectrofluorescence measurements of coals and petroleum source rocks. Int. J. Coal Geol. 1987, 7, 85–104. 10.1016/0166-5162(87)90014-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tribovillard N.; Algeo T. J.; Lyons T.; Riboulleau A. Trace metals as paleoredox and paleoproductivity proxies: an update. Chem. Geol. 2006, 232, 12–32. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2006.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. M.; Davis A.; Cook A. C.; Murchison D. G.; Scott E. Provincialism and correlations between some properties of vitrinites. Int. J. Coal Geol. 1984, 3, 315–331. 10.1016/0166-5162(84)90002-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidt G.; Littke R. Comparative organic petrology of interlayered sandstones, siltstones, mudstones and coals in the Upper Carboniferous Ruhr basin, Northwest Germany, and their thermal history and methane generation. Geol. Rundsch. 1989, 78, 375–390. 10.1007/bf01988371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gentzis T.; Goodarzi F.. A review of the use of bitumen reflectance in hydrocarbon exploration with examples from Melville Island, Arctic Canada. Applications of Thermal Maturity Studies to Energy Exploration; Rocky Mountain Section (SEPM), 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Khorasani G. K.; Michelsen J. K. The thermal evolution of solid bitumens, bitumen reflectance, and kinetic modeling of reflectance: application in petroleum and ore prospecting. Energy Sources 1993, 15, 181–204. 10.1080/00908319308909024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landis C. R.; Castaño J. R. Maturation and bulk chemical properties of a suite of solid hydrocarbons. Org. Geochem. 1995, 22, 137–149. 10.1016/0146-6380(95)90013-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Odusina E.; Sigal R. F. Laboratory NMR measurements on methane saturated Barnett Shale samples. Petrophysics 2011, 52, 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ozen A. E.Comparisons of T1 and T2 NMR relaxations on shale cuttings. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oklahoma Norman, OK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tinni A.; Odusina E.; Sulucarnain I.; Sondergeld C.; Rai C.. NMR Response of Brine, Oil and Methane in Organic Rich Shales; Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Sarmiento M.-F.; Ramiro-Ramirez S.; Berthe G.; Fleury M.; Littke R. Geochemical and petrophysical source rock characterization of the Vaca Muerta Formation, Argentina: Implications for unconventional petroleum resource estimations. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2017, 184, 27–41. 10.1016/j.coal.2017.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hürlimann M. D.; Venkataramanan L.; Flaum C. The diffusion–spin relaxation time distribution function as an experimental probe to characterize fluid mixtures in porous media. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 10223–10232. 10.1063/1.1518959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn K. E.; Birdwell J. E. Updated methodology for nuclear magnetic resonance characterization of shales. J. Magn. Reson. 2013, 233, 17–28. 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinberg R. L.; Horsfield M. A. Transverse relaxation processes in porous sedimentary rock. J. Magn. Reson. 1990, 88, 9–19. 10.1016/0022-2364(90)90104-h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleury M.; Romero-Sarmiento M. Characterization of shales using T1–T2 NMR maps. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2016, 137, 55–62. 10.1016/j.petrol.2015.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worden R. H.; Smalley P. C.; Oxtoby N. H. Gas souring by thermochemical sulfate reduction at 140 C. AAPG Bull. 1995, 79, 854–863. 10.1306/8D2B1BCE-171E-11D7-8645000102C1865D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar J.; Davis D.; Camacho C.; Alvarez P. J. J. Biogenic versus thermogenic H2S source determination in Bakken wells: considerations for biocide application. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016, 3, 127–132. 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holubnyak Y.; Bremer J. M.; Hamling J. A.; Huffman B. L.; Mibeck B.; Klapperich R. J.; Smith S. A.; Sorensen J. A.; Harju J. A.. Understanding the Souring at Bakken Oil Reservoirs; Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fichter J.; Wunch K.; Moore R.; Summer E.; Braman S.; Holmes P.. How Hot is too Hot for Bacteria? A Technical Study Assessing Bacterial Establishment in Downhole Drilling, Fracturing and Stimulation Operations; NACE International, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Breit G. N.; Wanty R. B. Vanadium accumulation in carbonaceous rocks: a review of geochemical controls during deposition and diagenesis. Chem. Geol. 1991, 91, 83–97. 10.1016/0009-2541(91)90083-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanty R. B.; Goldhaber M. B. Thermodynamics and kinetics of reactions involving vanadium in natural systems: Accumulation of vanadium in sedimentary rocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1992, 56, 1471–1483. 10.1016/0016-7037(92)90217-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman D. J.; Nagy B. Solid bitumens: an assessment of their characteristics, genesis, and role in geological processes. Terra Nova 1996, 8, 114–128. 10.1111/j.1365-3121.1996.tb00736.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saintilan N. J.; Spangenberg J. E.; Chiaradia M.; Chelle-Michou C.; Stephens M. B.; Fontboté L. Petroleum as source and carrier of metals in epigenetic sediment-hosted mineralization. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8283. 10.1038/s41598-019-44770-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Diaz M. A.; Morse J. W. Pyritization of trace metals in anoxic marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1992, 56, 2681–2702. 10.1016/0016-7037(92)90353-k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg E. P.; Van Den Berg C. M. G.; Boussemart M.; Davison W. Speciation and cycling of trace metals in Esthwaite Water: a productive English lake with seasonal deep-water anoxia. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1997, 61, 5233–5253. 10.1016/s0016-7037(97)00316-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. W.; Luther G. W. III Chemical influences on trace metal-sulfide interactions in anoxic sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1999, 63, 3373–3378. 10.1016/s0016-7037(99)00258-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Francois R. A study on the regulation of the concentrations of some trace metals (Rb, Sr, Zn, Pb, Cu, V, Cr, Ni, Mn and Mo) in Saanich Inlet sediments, British Columbia, Canada. Mar. Geol. 1988, 83, 285–308. 10.1016/0025-3227(88)90063-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson L. B.; Neil W.. Sediment-Hosted Stratiform Deposits of Copper, Lead, and Zinc; Society of Economic Geologists, 1981; pp 139–178. [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen S. R.; Afeworki M.; Gorbaty M. L.; Sansone M.; Kwiatek P. J.; Walters C. C.; Freund H.; Siskin M.; Bence A. E.; Curry D. J.; Solum M.; Pugmire R. J.; Vandenbroucke M.; Leblond M.; Behar F. Direct characterization of kerogen by X-ray and solid-state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance methods. Energy Fuels 2007, 21, 1548–1561. 10.1021/ef060321h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hackley P. C.; Lewan M. Understanding and distinguishing reflectance measurements of solid bitumen and vitrinite using hydrous pyrolysis: implications to petroleum assessment. AAPG Bull. 2018, 102, 1119–1140. 10.1306/08291717097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khatibi S.; Ostadhassan M.; Tuschel D.; Gentzis T.; Carvajal-Ortiz H. Evaluating molecular evolution of kerogen by raman spectroscopy: correlation with optical microscopy and rock-eval pyrolysis. Energies 2018b, 11, 1406. 10.3390/en11061406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lomando A. J. The influence of solid reservoir bitumen on reservoir quality. AAPG Bull. 1992, 76, 1137–1152. 10.1306/BDFF8984-1718-11D7-8645000102C1865D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]