Abstract

Semiclathrate hydrates of tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride (TBAF) are potential CO2 capture media because they can capture CO2 at near ambient temperature under moderate pressure such as below 1 MPa. In addition to other semiclathrate hydrates, CO2 capture properties of TBAF hydrates may vary with formation conditions such as aqueous composition and pressure because of their complex hydrate structures. In this study, we investigated CO2 capture properties of TBAF hydrates for simulated flue gas, that is, CO2 + N2 gas, by the gas separation test with three different parameters for each pressure and aqueous composition of TBAF in mass fraction (wTBAF). The CO2 capture amount in TBAF hydrates with wTBAF = 0.10 was smaller than that obtained with wTBAF = 0.20 and 0.30. The results found that gas pressure greatly changed the CO2 capture amount in TBAF hydrates, and the aqueous composition highly affected CO2 selectivity. The crystal morphology and single-crystal structure analyses suggested that polymorphism of TBAF hydrates with congruent aqueous solution may lower both the CO2 capture amount and selectivity. Our present results proposed that an aqueous solution with wTBAF = 0.20 is advantageous for the CO2 capture from flue gas compared to near congruent solutions of TBAF hydrates (wTBAF = 0.30) and dilute solution (wTBAF = 0.10).

1. Introduction

The vast CO2 emission from industries is a major contributor of global warming.1 To control the atmospheric CO2 composition, CO2 capture technology is required2 for various gases, for example, CO2 + N2 flue gas from combustion of fossil fuels, CO2 + H2 gas from the power plant of integrated coal gasification combined cycle and CO2 + CH4 gas as biogas.3 Semiclathrate hydrate-based gas separation is proposed because of their moderate thermodynamic conditions for CO2 capture and release.4−8 Semiclathrate hydrates are one of the inclusion compounds formed from aqueous solutions of quaternary ammonium or phosphonium salts. Their crystal structures consist of a cage-like framework formed by hydrogen-bonded water molecules. There is a variety of ionic substances that form semiclathrate hydrates, for example, tetra-n-butylammonium (TBA)9−16 and tetra-n-butylphosphonium (TBP)10,11,14,17,18 for the cation and halide,13−16,19,20 hydroxide21,22 and carboxylate14,23−26 for the anion. TBA bromide (TBAB), TBA chloride (TBAC), TBP bromide (TBPB), and TBP chloride (TBPC) are widely used because of the high melting temperatures around 280 K of their hydrates.20,27,28 Semiclathrate hydrates have dodecahedral (D) water cages which can capture small gas molecules such as CH4, N2, and CO2 under their gas pressures29−31 similar to gas hydrates.32−34 Because of the significant stabilization by the inclusion of the ionic substances, the formation pressures of semiclathrate hydrates are much lower than those of gas hydrates, that is, <1 MPa for CO2 semiclathrate hydrate28,35 and ∼3 MPa for structure I CO2 gas hydrate32 around 280 K.

Because the semiclathrate hydrates have a lot of advantages such as high melting temperatures and less hazardous and nonvolatile properties, gas separation for simulated flue gas, that is, CO2 + N2 gas, has been studied a lot.4−8,36−41 Rapid CO2 capture and release by semiclathrate hydrates which are driven by small temperature window around 300 K is a great advantage for the CCS process compared to the potential CO2 absorption method such as using amine solution which requires a temperature around 400 K to release the captured CO2.42 The melting temperatures of semiclathrate hydrates can be widely changed by a variety of ionic substances and their aqueous composition differing from gas hydrates. In addition, particularly high CO2 selectivity of semiclathrate hydrates compared to structure II gas hydrates was found,6,43−45 although both of these hydrates only have D cages. This is likely due to irregular shapes of the D cages which are available in semiclathrate hydrates.46,47 Semiclathrate hydrates provide differently shaped D cages with various options for the ionic substances.18,22,46−49 Because these unique D cages may selectively capture gases, it is expected that semiclathrate hydrates have a further potential to improve their gas selectivity. In our previous studies, we investigated CO2 capture properties of TBAB, TBAC, TBPB, and TBPC hydrates for CO2 + N2 gas.6,40 It was found that TBAB hydrates have high CO2 selectivity due to the polymorphism of TBAB hydrates which may depend on the aqueous composition and pressure. It was also found that TBAB hydrates capture a comparable amount of CO2 with structure II gas hydrates.6 In addition, we reported that TBAC hydrates have higher CO2 selectivity than TBAB, TBPB, and TBPC hydrates, although the captured gas amount of TBAC hydrate is half or less than that of the others. X-ray diffraction analyses suggested that crystal structures are one of the dominant factors for controlling the CO2 selectivity of semiclathrate hydrates.40

TBA fluoride (TBAF) forms highly stable semiclathrate hydrate of which melting temperature is close to ambient temperature, that is, ∼300 K, under atmospheric pressure.50,51 The melting temperature of TBAF hydrates are the highest among semiclathrate hydrates of TBA and TBP halides.20,27,28,51 TBAF can capture CO2 at near ambient temperature, that is, around 300 K, under 1 MPa of CO2 pressure,52,53 which is approximately 10 K higher than that of TBAB and TBAC hydrates.35,54 In the previous studies, gas separation by TBAF hydrates for CO2 + N25,36 and CO2 + H255,56 gases were performed. Irregularly high CO2 selectivity of TBAF hydrates for CO2 + N2 gas was reported.36 On the other hand, the CO2 capture amount is also an important factor for gas separation because they are critical to designing CCS processes, that is, the amount of CO2 capture media required for the process.42,57 However, the CO2 capture amounts in TBAF hydrates from the CO2 + N2 gas are not fully understood.

TBAF hydrates mainly form tetragonal and cubic structures under atmospheric pressure.48,50,58 Hydration numbers of the tetragonal and cubic structures of TBAF hydrates are 32.858 (0.307 in TBAF mass fraction and 300.4 K of melting temperature50) and 29.748 (0.328 in TBAF mass fraction and 300.8 K of melting temperature), respectively. The cubic structure is unavailable with the TBAB, TBAC, TBPB, and TBPC hydrates. Because the gas capture amount and selectivity of semiclathrate hydrates vary with the crystal structures, the cubic structure of TBAF hydrates may have unique gas separation properties. It is reported that stable crystal structures of TBAF hydrates under hydrogen gas pressures change depending on the aqueous composition of TBAF and pressure51 as well as TBAB hydrates under krypton59 and CO2 + N260 gas pressures. Aqueous compositions of TBAF are an important parameter for gas capture because it usually controls stability of hydrate phases which may have different gas capture properties. In addition, the driving force for hydrate formation is highly dependent on the aqueous composition. When an initial aqueous composition differs from the congruent compositions of the hydrate crystals, the driving force decreases because of the aqueous composition change during the hydrate formation, and the gas would be captured insufficiently. Therefore, the performing gas separation test with the parameters of aqueous composition and pressure for CO2 + N2 mixed gas is necessary for understanding the complex CO2 capture properties of TBAF hydrates against flue gas.

In this paper, we report the parametric study on the CO2 + N2 mixed gas separation by TBAF hydrates. A batch-type gas separation process was employed. Molar gas compositions of CO2 + N2 mixed gas were ∼0.12 and ∼0.88, respectively. We used TBAF aqueous solutions with compositions of 0.10, 0.20, and 0.30 in mass fraction under three different pressure levels, that is, 1, 3, and 5 MPa. The aqueous composition of 0.30 is almost consistent with the congruent compositions of the two main structures, that is, tetragonal and cubic structures. Effects of aqueous composition and pressures on the CO2 capture amount and selectivity of TBAF hydrates are discussed. We also performed X-ray diffraction measurements for the identification of the crystal structure of the TBAF hydrate formed under CO2 + N2 gas pressure. We also discussed the effect of crystal structures on the CO2 capture amount and selectivity of TBAF hydrates.

2. Results and Discussion

The obtained data for the total

gas capture amount in the hydrate

phase (n̅H), the CO2 composition

of captured gas in the hydrate phase (ϕ̅CO2), the CO2 capture amount in the hydrate phase  , separation factor

, separation factor  and their estimated uncertainties

with

95% reliability U were shown in Table 1 and Figures 1–6. The test parameters, that is, aqueous composition of TBAF in mass

fraction (wTBAF), temperature (T), and pressure (P), were also summarized

in Table 1. As shown

in Figure 1, at 5 MPa, n̅H linearly increased with increasing

aqueous concentration of TBAF. n̅H slightly increased at 3 MPa with wTBAF = 0.30 from that with wTBAF = 0.20,

but it decreased at 1 MPa. This behavior with the aqueous composition

of TBAF is peculiar, because the aqueous composition of wTBAF = 0.30 is close to the congruent compositions of

TBAF hydrates, that is, wTBAF = 0.307

and 0.328. Congruent aqueous solutions should provide maximum gas

capture amount because the driving force is kept during hydrate formation

without dilution or condensation of the aqueous solutions. However,

the presently obtained n̅H suggested

that unusual hydrate formation occurred under pressures of 3 MPa and

below. Comparison of the gas capture amount between this and the previous

study is shown in Figure 2. This figure shows that the n̅H with wTBAF = 0.30 was comparable

with TBAC hydrates. The presently obtained n̅H were less than half that of TBAB, TBPB, and TBPC hydrates.

and their estimated uncertainties

with

95% reliability U were shown in Table 1 and Figures 1–6. The test parameters, that is, aqueous composition of TBAF in mass

fraction (wTBAF), temperature (T), and pressure (P), were also summarized

in Table 1. As shown

in Figure 1, at 5 MPa, n̅H linearly increased with increasing

aqueous concentration of TBAF. n̅H slightly increased at 3 MPa with wTBAF = 0.30 from that with wTBAF = 0.20,

but it decreased at 1 MPa. This behavior with the aqueous composition

of TBAF is peculiar, because the aqueous composition of wTBAF = 0.30 is close to the congruent compositions of

TBAF hydrates, that is, wTBAF = 0.307

and 0.328. Congruent aqueous solutions should provide maximum gas

capture amount because the driving force is kept during hydrate formation

without dilution or condensation of the aqueous solutions. However,

the presently obtained n̅H suggested

that unusual hydrate formation occurred under pressures of 3 MPa and

below. Comparison of the gas capture amount between this and the previous

study is shown in Figure 2. This figure shows that the n̅H with wTBAF = 0.30 was comparable

with TBAC hydrates. The presently obtained n̅H were less than half that of TBAB, TBPB, and TBPC hydrates.

Table 1. Conditions and Results of the Gas Separation Testa.

| case | number of test | T/Kb | P/MPab | n̅H/mmol | U(n̅H)/mmol | ϕ̅CO2 | U(ϕ̅CO2) |

|

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w10-1 MPa | 7 | 289.6 | 1.00 | 6.9 | 0.3 | 0.388 | 0.017 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 4.5 | 0.4 | ||||

| w10-3 MPa | 8 | 290.6 | 3.01 | 17.5 | 0.8 | 0.405 | 0.019 | 7.0 | 0.2 | 4.6 | 0.5 | ||||

| w10-5 MPa | 8 | 291.6 | 5.01 | 23.9 | 1.2 | 0.442 | 0.025 | 10.3 | 0.3 | 5.0 | 0.6 | ||||

| w20-1 MPa | 5 | 295.2 | 1.01 | 13.9 | 0.6 | 0.374 | 0.014 | 5.2 | 0.2 | 5.2 | 0.4 | ||||

| w20-3 MPa | 5 | 296.2 | 3.01 | 35.0 | 1.5 | 0.371 | 0.015 | 13.0 | 0.5 | 4.9 | 0.4 | ||||

| w20-5 MPa | 7 | 297.2 | 5.00 | 49.6 | 1.8 | 0.352 | 0.013 | 17.2 | 0.5 | 4.1 | 0.3 | ||||

| w30-1 MPa | 5 | 298.2 | 1.01 | 12.6 | 0.5 | 0.219 | 0.010 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 0.2 | ||||

| w30-3 MPa | 6 | 298.6 | 3.01 | 42.0 | 1.5 | 0.238 | 0.010 | 9.9 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.2 | ||||

| w30-5 MPa | 5 | 299.2 | 5.01 | 74.1 | 2.9 | 0.247 | 0.011 | 18.2 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 0.2 |

Overlines and U denote weighted averages of the obtained values of each condition and their uncertainties with 95% reliability, respectively.

Measurement uncertainties with 95% reliability for T and P are 0.3 K and 0.01 MPa, respectively.

Figure 1.

Total gas capture amount in TBAF hydrates (n̅H). The symbols denote test pressures: □ with orange, 5 MPa; △ with blue, 3 MPa; and ○ with red, 1 MPa. Error bars denote uncertainties U with 95% reliability.

Figure 6.

Comparison of S.F. between this and the previous40 study. Present results were shown as weighted averages of the obtained values under each condition. The symbols denote test pressures: ○ with orange, wTBAF = 0.30 in this study; ○ with blue, wTBAF = 0.20 in this study; ○ with red, wTBAF = 0.10 in this study; △ with purple, wTBAB = 0.32;40 △ with light blue, wTBAB = 0.20;40 □ yellow, wTBAC = 0.20;40 ◊ with pink, wTBPB = 0.20;40 and × with green, wTBPC = 0.20.40 Error bars denote uncertainties U with 95% reliability.

Figure 2.

Comparison of nH between this study and the previous40 study. Present results were shown as weighted averages of the obtained values under each condition. The symbols denote test pressures: ○ with orange, wTBAF = 0.30 in this study; ○ with blue, wTBAF = 0.20 in this study; ○ with red, wTBAF = 0.10 in this study; △ with purple, wTBAB = 0.32;40 △ with light blue, wTBAB = 0.20;40 □ yellow, wTBAC = 0.20;40 ◊ with pink, wTBPB = 0.20;40 and × with green, wTBPC = 0.20.40 Error bars denote uncertainties with 95% reliability.

Based on the aqueous composition change during the tests with wTBAF = 0.10 (see Figure S10 and Table S2 in the Supporting Information), the TBAF in the aqueous phase was comparably consumed at 1, 3, and 5 MPa, that is, 26–30 mmol. On the other hand, nH increased with the test pressure increase. Therefore, the TBAF hydrates captured more gas per TBAF at high pressure.

ϕ̅CO2 are shown in Figure 3. Because CO2 compositions in gas phases before hydrate formation were approximately 0.10–0.11, CO2 was enriched in the hydrate phase with twice to four times higher compositions by the present one-stage separation process. Although the ϕ̅CO2 with wTBAF = 0.10 and 0.20 were comparable, that is, around 0.40 in mole fraction, the ϕ̅CO2 with wTBAF = 0.30 were evidently low, that is, ∼0.25 in mole fraction. This suggests that higher CO2 selectivity can be obtained with wTBAF = 0.10 and 0.20 rather than with wTBAF = 0.30, which is close to the congruent compositions of TBAF hydrates, that is, wTBAF = 0.307 and 0.328. Pressure dependency of ϕ̅CO2 is not clearly observed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

CO2 composition of captured gas in TBAF hydrates (ϕ̅CO2). The symbols denote test pressures: □ with orange, 5 MPa; △ with blue, 3 MPa; and ○ with red, 1 MPa. Error bars denote uncertainties U with 95% reliability.

As well as n̅H,  increased with the test pressure increase,

as shown in Figure 4. At 1 and 3 MPa,

increased with the test pressure increase,

as shown in Figure 4. At 1 and 3 MPa,  was the largest with wTBAF = 0.20 because of the higher CO2 selectivity

compared to that with wTBAF = 0.30 shown

in Figure 3. It is

noteworthy that wTBAF = 0.30 is close

to congruent compositions of the TBAF hydrate crystals, that is, 0.307

and 0.328, rather than wTBAF = 0.20; however,

was the largest with wTBAF = 0.20 because of the higher CO2 selectivity

compared to that with wTBAF = 0.30 shown

in Figure 3. It is

noteworthy that wTBAF = 0.30 is close

to congruent compositions of the TBAF hydrate crystals, that is, 0.307

and 0.328, rather than wTBAF = 0.20; however,  with wTBAF =

0.30 is almost equal to or less than that with wTBAF = 0.20. From Figures 3 and 4, it is found that the

dense aqueous solution with wTBAF = 0.30

reduces both CO2 selectivity and the capture amount compared

to wTBAF = 0.20. Because n̅H increased with wTBAF = 0.30,

as shown in Figure 1, another hydrate phase may form with wTBAF = 0.30, which prefers N2 gas compared to the hydrate

phase formed with wTBAF = 0.10 and 0.20.

The presently obtained

with wTBAF =

0.30 is almost equal to or less than that with wTBAF = 0.20. From Figures 3 and 4, it is found that the

dense aqueous solution with wTBAF = 0.30

reduces both CO2 selectivity and the capture amount compared

to wTBAF = 0.20. Because n̅H increased with wTBAF = 0.30,

as shown in Figure 1, another hydrate phase may form with wTBAF = 0.30, which prefers N2 gas compared to the hydrate

phase formed with wTBAF = 0.10 and 0.20.

The presently obtained  were less than half that of TBAB, TBAC,

TBPB, and TBPC hydrates reported in our previous study, as shown in Figure 5. Therefore, the

TBAF hydrates have clearly different CO2 capture properties

from them.

were less than half that of TBAB, TBAC,

TBPB, and TBPC hydrates reported in our previous study, as shown in Figure 5. Therefore, the

TBAF hydrates have clearly different CO2 capture properties

from them.

Figure 4.

CO2 capture amount in TBAF hydrates  . The symbols denote test pressures: □

with orange, 5 MPa; △ with blue, 3 MPa; and ○ with red,

1 MPa. Error bars denote uncertainties U with 95%

reliability.

. The symbols denote test pressures: □

with orange, 5 MPa; △ with blue, 3 MPa; and ○ with red,

1 MPa. Error bars denote uncertainties U with 95%

reliability.

Figure 5.

Comparison of  between this and the previous40 study. Present results were shown as weighted

averages of the obtained values under each condition. The symbols

denote test pressures: ○ with orange, wTBAF = 0.30 in this study; ○ with blue, wTBAF = 0.20 in this study; ○ with red, wTBAF = 0.10 in this study; △ with purple, wTBAB = 0.32;40 △

with light blue, wTBAB = 0.20;40 □ yellow, wTBAC = 0.20;40 ◊ with pink, wTBPB =

0.20;40 and × with green, wTBPC = 0.20.40 Error

bars denote uncertainties U with 95% reliability.

between this and the previous40 study. Present results were shown as weighted

averages of the obtained values under each condition. The symbols

denote test pressures: ○ with orange, wTBAF = 0.30 in this study; ○ with blue, wTBAF = 0.20 in this study; ○ with red, wTBAF = 0.10 in this study; △ with purple, wTBAB = 0.32;40 △

with light blue, wTBAB = 0.20;40 □ yellow, wTBAC = 0.20;40 ◊ with pink, wTBPB =

0.20;40 and × with green, wTBPC = 0.20.40 Error

bars denote uncertainties U with 95% reliability.

The obtained  are shown in Figure 6. This figure shows

that the CO2 selectivity with wTBAF = 0.30 were clearly

lower than that with wTBAF = 0.10 and

0.20.

are shown in Figure 6. This figure shows

that the CO2 selectivity with wTBAF = 0.30 were clearly

lower than that with wTBAF = 0.10 and

0.20.  with wTBAF =

0.10 and 0.20 were comparable with that of TBAB, TBPB, and TBPC hydrates.

This tendency of CO2 selectivity, that is, high S.F. with

dilute aqueous solution, was also found for TBAB, TBAC, TBPB hydrates,39 and TBAF hydrates.36 However, we did not observe both strong pressure dependencies of

S.F. and the irregularly high S.F., that is, 36.98, which are reported

in the previous study.36

with wTBAF =

0.10 and 0.20 were comparable with that of TBAB, TBPB, and TBPC hydrates.

This tendency of CO2 selectivity, that is, high S.F. with

dilute aqueous solution, was also found for TBAB, TBAC, TBPB hydrates,39 and TBAF hydrates.36 However, we did not observe both strong pressure dependencies of

S.F. and the irregularly high S.F., that is, 36.98, which are reported

in the previous study.36

We optically

observed TBAF hydrate crystals, as shown in Figure 7. In all the present

conditions, we observed thin columnar shaped crystals, as shown in Figure 7a–c, which

were similar to the crystals of TBAB hydrates,35,40,61 TBAC hydrates,28,40 and TBPC hydrates40 reported in the previous

studies. With wTBAF = 0.30, distinctly

shaped polyhedral crystals, which were suggested to have the cubic

structure,51,62 were observed, as shown in Figures 7d and S11 in the Supporting Information. We suppose that two different

crystal structures were formed with wTBAF = 0.30, which may be the polymorphism of TBAF hydrates. The two-stage

pressure drops shown in Figure S5c may

be occurred by the formation of the two different hydrate phases.

Polymorphism of TBAF hydrates is also supported by inconsistent nH with wTBAF = 0.30

at each pressure level shown in Figure S6 in the Supporting Information, which was probably caused by fractionation

of the two comparably stable hydrate phases. Less  and lower

and lower  with wTBAF =

0.30 shown in Figures 5 and 6 are likely to be caused by this polymorphism

of the TBAF hydrates. Such two-stage pressure drop is also observed

for TBAB6,40 and TBPC40 hydrates

in our previous study.

with wTBAF =

0.30 shown in Figures 5 and 6 are likely to be caused by this polymorphism

of the TBAF hydrates. Such two-stage pressure drop is also observed

for TBAB6,40 and TBPC40 hydrates

in our previous study.

Figure 7.

Single crystals of TBAF hydrates formed during gas separation tests. Photographs (a) run 2 of w10-3 MPa, (b) run 2 of w20-3 MPa, (c) run 5 of w30-3 MPa, and (d) run 1 of w30-3 MPa were taken within 10 min after the crystallization in gas separation tests.

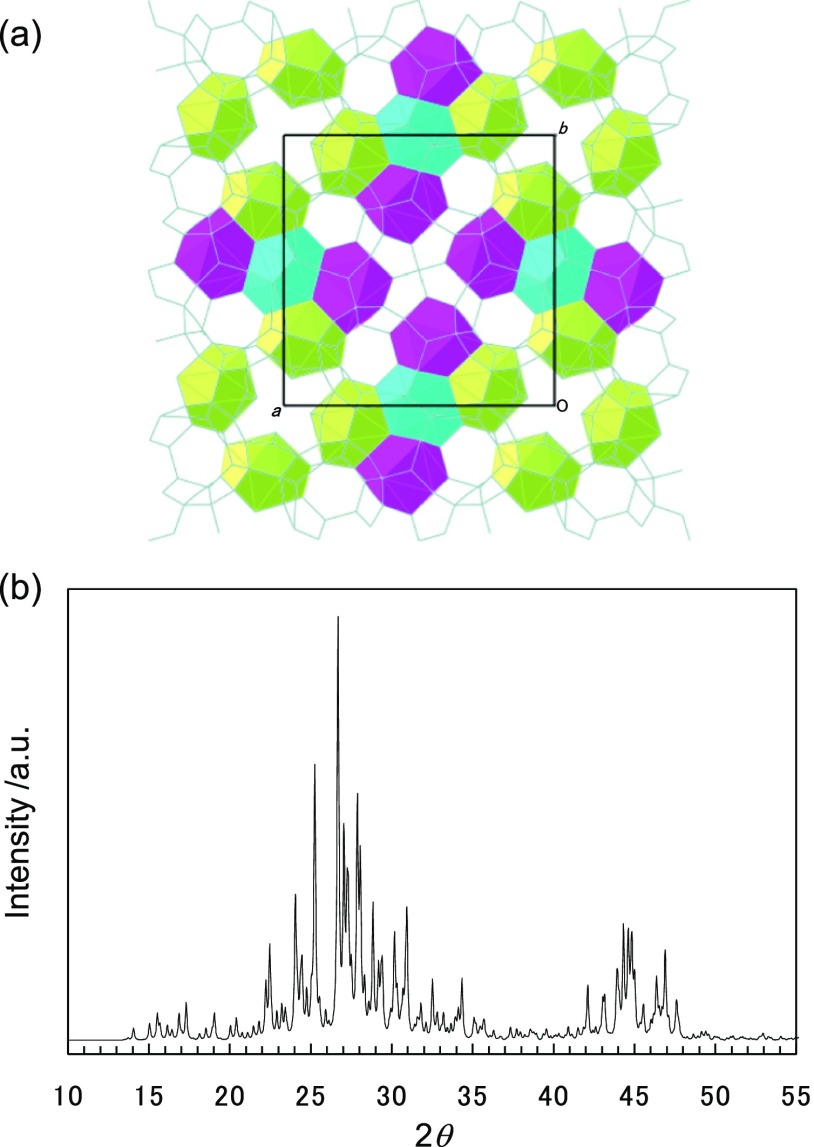

We performed single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) on TBAF hydrates formed under CO2 + N2 gas pressure. The obtained single crystals are shown in Figure 8. As well as the present gas separation tests and the previous studies,63 the columnar shaped crystals are obtained. The determined crystal lattice of the TBAF hydrates is a = 23.301 (3) Å and c = 12.179 (2) Å at 123 K with tetragonal cell and space group of P42/m which is identical with Jeffrey’s type III structure.11 The unit cell size is consistent with the references regarding TBAF hydrates formed under atmospheric pressure.50,58 From the present SCXRD data, we found the three distinct D cages as shown in the Figure 9a. These are three different types of D cages: a relatively-regular D cage and two differently distorted D cages. In the unit cell, there are two of the relatively-regular D cages and four sets of the two distorted D cages, that is, 10 D cages in total. Two D cages per TBAF are available for gas capture. This is a clear reason for the small gas capture amount of the TBAF hydrates compared to the orthorhombic semiclathrate hydrates formed with TBAB, TBPB, and TBPC40 in which three D cages per TBA or TBP cation are available for gas.10 The present SCXRD data are inadequate for further refinement on complex disorder of TBA cation and discriminating CO2 and N2 incorporated in the D cages.

Figure 8.

Single crystals of TBAF hydrates formed under CO2 + N2 gas pressure for SCXRD measurements.

Figure 9.

Results for the present SCXRD analysis on the TBAF hydrate formed under CO2 + N2 gas pressure. (a) Arrangement of the three distinct D cages discriminated by colors: light blue, relatively-regular D cage; magenta, distorted D cage; and light green, the other distorted D cage. Residual space should be filled with TBA cations. (b) PXRD pattern simulated from the present SCXRD data. This pattern is simulated with a Cu Kα source (1.54178 Å).

In Figure 9b, the powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern with Cu Kα source is simulated from the present SCXRD data for identification of the present hydrate structure and comparison with previous studies. The simulated PXRD pattern agrees with the reference data for the tetragonal structure.16,64 The present hydrate structure is identical to the TBAC hydrate formed under CO2 + N2 gas pressure obtained in our previous study.40 The unit cell dimension of the TBAC hydrate formed under CO2 + N2 gas pressure was a = 23.870 (3) Å and c = 12.497 (3) Å at 123 K.40 The present unit cell of the TBAF hydrate is approximately 7% smaller than that of the TBAC hydrate, that is, volumes of their unit cells are 6612(2) and 7121(2) Å3, respectively. A plausible reason for a large size difference is the bond lengths between water–chloride and water–fluoride. Based on Figure 6, the CO2 selectivity of TBAF hydrates were lower than that of TBAC hydrates, though the nH of them were comparable, that is, 74 mmol for TBAF with wTBAF = 0.30 and 77 mmol for TBAC with wTBAC = 0.20, as shown in Figure 2. The present results of SCXRD suggest that the CO2 capture properties of the tetragonal structure formed with a TBA cation is highly affected by the anions which may cause a change in the unit cell volume because of the difference in bond length between water molecules.

3. Conclusions

We investigated TBAF hydrate-based CO2 capture properties for CO2 + N2 mixed gas, which simulates flue gas. Reliable datasets were obtained by exhaustive parametric gas separation tests at near ambient temperature. The results showed that high pressure increased gas capture amounts of TBAF hydrates. The largest CO2 capture amounts were obtained with wTBAF = 0.20 at 1 and 3 MPa due to higher CO2 selectivity compared to wTBAF = 0.10 and 0.30. SCXRD measurements determined that the TBAF hydrates mainly formed the tetragonal structure in the present formation conditions. The presently obtained separation factor of TBAF hydrates was lower than that of TBAC hydrates, which also form the tetragonal structure. It is suggested that the CO2 capture property of the tetragonal structure formed with a TBA cation is highly affected by the anions, while the orthorhombic structure did not show such behavior with TBAB, TBPB, and TBPC in our previous study. Polymorphism with two different TBAF hydrate phases are also suggested from the crystal morphology during gas separation tests with wTBAF = 0.30. In these tests, a comparably stable hydrate phase which is supposed to be the cubic structure with a small CO2 capture amount and low CO2 selectivity formed together with the tetragonal hydrate phase. Congruent solutions of TBAF hydrates are found to be disadvantageous for the CO2 capture amount and CO2 selectivity of TBAF hydrates. For the CO2 capture process based on TBAF hydrates at low operation pressure, for example, 1 MPa, our present results proposed that an aqueous solution with wTBAF = 0.20 is advantageous for CO2 capture from flue gas compared to near congruent solutions (wTBAF = 0.30) and dilute solutions (wTBAF = 0.10).

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

We used CO2 + N2 mixed gas (Taiyo Nippon Sanso, Co., Tokyo) of which composition is 0.151 and 0.849 in mole fraction, respectively. TBAF trihydrate (mass fraction of TBAF: 0.84) (Sigma-Aldrich, Co., Missouri) was used. The used water was deionized, filtrated by activated carbon, sterilized by an ultraviolet lamp, and finally filtrated by a hollow fiber filter. The electrical resistivity of the obtained water was ≥18.2 MΩ. TBAF aqueous solutions were gravimetrically prepared with the aid of an electronic balance (GX-6100, A&D Co., Tokyo) with 0.02 g of uncertainty with 95% reliability.

4.2. Gas Separation Tests

The main parts of an apparatus for gas separation tests are a hydrate formation reactor, a water bath made of polymethyl methacrylate, a proportional-integral-derivative controlled heater, and a cooler. The schematic of the hydrate formation reactor is shown in Figure 10. The inner dimension of the reactor is 80 mm in diameter, 155 mm in height, and 800 ± 20 cm3 in volume. The reactor has two glass windows for observing inside, a strain-gauge pressure transducer (VPRTF-A2-10MPaW-5, Valcom, Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan), a platinum resistance thermometer at the bottom (Pt100 Class B 2 mA, NRHS1-0, Chino, Co., Tokyo), a tube with a valve for sampling of the aqueous solution on the bottom, a one-side sealed tube for thermometer insert on the lid, and an electromagnetically induced stirrer on the lid. Gas compositions were analyzed using a gas chromatograph (GC) (GC-2014, Shimadzu, Co., Kyoto, Japan) with a thermal conductivity detector. The used carrier gas for GC is argon (≥0.99999 in mole fraction certified purity, Taiyo Nippon Sanso, Co., Tokyo) and the separation column is a packed column (ShinCarbon ST 50/80, Shinwa Chemical Industries, Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). The schematic diagram of the apparatus was provided in our previous paper.40

Figure 10.

Schematic of a hydrate formation reactor used in this study. (a) Hydrate formation reactor, (b) magnetic stirrer, (c) sealed tube, (d) platinum resistance thermometer, (e) strain-gauge pressure transducer, (f) tube with a valve for sampling of aqueous solution, and (g) tube with a valve for gas supply, release and sampling.

TBAF aqueous solutions were prepared with 0.10, 0.20, and 0.30 on a mass basis. We used gas pressures (P) at three different levels, that is, 1, 3, and 5 MPa. The test temperatures (T) were set to have 3 K of subcooling temperature based on the phase equilibrium data. The phase equilibrium data were measured before gas separation tests to determine the test temperatures, and are shown in Figure S1 in the Supporting Information. The reactor was charged with 300 g of TBAF aqueous solution and placed into the bath. After the evacuation of the air inside the reactor by a vacuum pump, CO2 + N2 mixed gas was supplied into the reactor up to test pressures. A magnetic stirrer started to mix gas and liquid for gas dissolution into the aqueous phase. When the pressure becomes constant as gas dissolution ceased, we sampled the gas into a sampling vessel having 10 cm3 volume with 0.2 MPa for GC analysis. Because the sampled amount is small enough when compared to the gas charged in the reactor, the present sampling process scarcely changed the reactor state. Then, we induced crystallization by inserting a stainless steel rod precooled by liquid nitrogen into the sealed tube, and started stirring with 500 rpm. Because size of the sealed tube is 1/4 in. of outer diameter and small enough, the sealed tube temperature immediately returned to be the system temperature, and system temperature change was not detected by the thermometers set in the aqueous phase. In order to know the pressure drop caused by TBAF hydrate formation, the first run of each condition was performed for 3 h or longer. After the second run, the test was terminated when the rate of the pressure drop was below 10 kPa/h. At the end of the test, the gas composition in the gas phase was analyzed. We used REFPROP 9.165,66 for calculating the gas phase density. The total gas capture amount in the hydrate phase (nH) is obtained as follows

| 1 |

where ρG and ρ′G are the

density of the gas phase before and after hydrate

formation, respectively. VG is the volume

of gas phase. The CO2 capture amount in the hydrate phase

( ) is determined by the following equation

) is determined by the following equation

| 2 |

where  and

and  are the CO2 amount in the gas

phase before and after hydrate formation, respectively. yCO2 and

are the CO2 amount in the gas

phase before and after hydrate formation, respectively. yCO2 and  are CO2 mole fractions in the

gas phase before and after hydrate formation obtained by GC, respectively.

The N2 amount in the gas phase before (

are CO2 mole fractions in the

gas phase before and after hydrate formation obtained by GC, respectively.

The N2 amount in the gas phase before ( ) and after (

) and after ( ) hydrate formation were obtained in the

same manner with

) hydrate formation were obtained in the

same manner with  and

and  . The N2 capture amount in the

hydrate phase (

. The N2 capture amount in the

hydrate phase ( )

was also obtained in the same manner with

)

was also obtained in the same manner with  . Here,

. Here,  is the CO2 amount captured

only

from the gas phase. Captured CO2 from TBAF aqueous solution

was not counted in

is the CO2 amount captured

only

from the gas phase. Captured CO2 from TBAF aqueous solution

was not counted in  because it is presently not possible

to

estimate the amount of formed TBAF hydrates. Based on the literature,

TBAB which is analogous to TBAF scarcely changes CO2 solubility

from pure water.67 An empirical correlation

also shows that fluoride anion slightly decreases CO2 solubility

from pure water, that is, salting-out effect.68 Therefore, we consider that the CO2 solubility of TBAF

aqueous solution is also comparable with that of pure water, and CO2 moved from the aqueous phase to the TBAF hydrate phase is

much smaller than CO2 captured from the gas phase. Thus,

because it is presently not possible

to

estimate the amount of formed TBAF hydrates. Based on the literature,

TBAB which is analogous to TBAF scarcely changes CO2 solubility

from pure water.67 An empirical correlation

also shows that fluoride anion slightly decreases CO2 solubility

from pure water, that is, salting-out effect.68 Therefore, we consider that the CO2 solubility of TBAF

aqueous solution is also comparable with that of pure water, and CO2 moved from the aqueous phase to the TBAF hydrate phase is

much smaller than CO2 captured from the gas phase. Thus,  is less than the actual CO2 capture

amount in TBAF hydrates, and we do not overestimate them. The CO2 composition of captured gas in the hydrate phase (ϕCO2) was calculated as follows

is less than the actual CO2 capture

amount in TBAF hydrates, and we do not overestimate them. The CO2 composition of captured gas in the hydrate phase (ϕCO2) was calculated as follows

| 3 |

Separation factor (S.F.) is given by the following equation

| 4 |

To obtain statistically reliable data, all the gas separation tests

were repeated 5–8 times. We averaged the obtained data with

weighting by their uncertainties. The averaged results are denoted

by the symbols with over bars in this article/study/file. All the

raw data are provided in Figures S3–S9 and Table S1 in the Supporting Information. For the tests with w = 0.10, the aqueous solution was also analyzed by a refractometer.

We calculated TBAF consumption the in aqueous phase based on obtained

aqueous composition changes determined by the refractometer. The calculation

processes are detailed in the Supporting Information. Measurement uncertainties with 95% reliability for T, P, aqueous composition of TBAF in mass fraction

(wTBAF), and gas phase composition are

0.3 K, 0.01 MPa, 0.006 in mass fraction and 0.002 in mole fraction,

respectively. Procedures of uncertainty estimation for nH,  , ϕCO2, and

S.F. are described in the Supporting Information.

, ϕCO2, and

S.F. are described in the Supporting Information.

4.3. X-ray Diffraction Analysis

The TBAF hydrate formed under CO2 + N2 gas pressure was characterized by a SCXRD analysis. An apparatus for single-crystal formation under CO2 + N2 gas pressure consists of a hydrate formation reactor, a temperature controlled bath, a pressure sensor (GP-M100, KEYENCE, Co., Osaka, Japan), and a thermometer (EcoScan Temp 6, Eutech Instruments Pte Ltd., Singapore). About 3 g of TBAF aqueous solution with wTBAF = 0.20 was supplied into the reactor. After three times repetition of evacuating air inside of the reactor by a vacuum pump and charge/discharge process with 1 MPa of N2 gas, CO2 + N2 mixed gas was injected into the reactor. The formation temperature and pressure were approximately 298 K and 3 MPa, respectively. After the TBAF hydrates crystals grew, they were separated from the aqueous solution, and cooled down to ∼250 K. Then, the residual CO2 + N2 gas was released from the reactor, and the crystals were taken out from the reactor. Measurement uncertainties with 95% reliability for temperature and pressure were 0.3 K and 0.02 MPa, respectively. A single crystal was selected and sized under cold nitrogen atmosphere at below 250 K, and subjected to a SCXRD analysis.

We used an imaging plate-type X-ray diffractometer (R-AXIS—RAPID-S, Rigaku, Co., Tokyo) with a Mo Kα radiation source (wave length: 0.71070 Å). The measurement temperature was 123.0 (3) K. The crystal structure was solved and refined by SHELX program.69 A PXRD pattern with Cu Kα source is simulated with the aid of Platon program70 and Powder4 program.71 Detailed measurement conditions and refinement results are provided in Table S3 in the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the research and development projects for application in promoting new policy of agriculture, forestry and fisheries by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF).

Glossary

Nomenclature

- T

temperature, K

- P

pressure, MPa

amount of CO2 in gas phase before hydrate formation, mmol

amount of CO2 in gas phase after hydrate formation, mmol

amount of N2 in gas phase after hydrate formation, mmol

- nH

amount of gas (CO2 + N2) in hydrate phase, mmol

amount of CO2 in hydrate phase, mmol

amount of N2 in hydrate phase, mmol

- VG

volume of gas phase, m3

- ρG

density of gas phase before hydrate formation, mmol/m3

- ρ′G

density of gas phase after hydrate formation, mmol/m3

- yCO2

composition of CO2 in gas phase before hydrate formation in mole fraction

composition of CO2 in gas phase after hydrate formation in mole fraction

- wTBAB

aqueous composition of TBAB in mass fraction

- wTBAC

aqueous composition of TBAC in mass fraction

- wTBAF

aqueous composition of TBAF in mass fraction

- wTBPB

aqueous composition of TBPB in mass fraction

- wTBPC

aqueous composition of TBPC in mass fraction

- ϕCO2

CO2 composition of captured gas in TBAF hydrates in mole fraction

- S.F.

separation factor

- U

expanded measurement uncertainty with 95% reliability

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b03442.

Three-phase equilibrium data of TBAF hydrates; flowchart of the calculation process; pressure trends during gas separation tests; total captured gas amount in TBAF hydrates; CO2 composition in TBAF hydrates; CO2 capture amount in TBAF hydrates; S.F. of TBAF hydrates; experimental conditions, results, and estimated uncertainties with 95 % reliability of the gas separation measurements; relationship between the total captured gas amount (nH) and TBAF consumption of the aqueous phase; aqueous composition changes in gas separation tests; single crystals of TBAF hydrates formed in gas separation tests; and formation conditions of the present TBAF hydrate formed under CO2 + N2 pressure and X-ray diffraction and structure data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; The Core Writing Team; Pachauri R. K., Meyer L. A., Eds.; IPCC, Geneva, 2015.

- Energy Technology Perspectives 2017; OECD/IEA: Paris, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thambimuthu K.; Soltanieh M.; Abanades J. C.; Allam R.; Bolland O.; Davison J.; Feron P.; Goede F.; Herrera A.; Iijima M.; Jansen D.; Leites I.; Mathieu P.; Rubin E.; Simbeck D.; Warmuzinski K.; Wilkinson M.; Williams R.; Jaschik M.; Lyngfelt A.; Span R.; Tanczyk M.; Abu-Ghararah Z.; Yashima T. In IPCC Special Report on Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage; Metz B., Davidson O., Coninck H., Loos M., Meyer L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2005; pp 105–178.

- Duc N. H.; Chauvy F.; Herri J.-M. CO2 capture by hydrate crystallization – A potential solution for gas emission of steelmaking industry. Energy Convers. Manage. 2007, 48, 1313–1322. 10.1016/j.enconman.2006.09.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Seo Y. Semiclathrate-based CO2 capture from flue gas mixtures: An experimental approach with thermodynamic and Raman spectroscopic analyses. Appl. Energy 2015, 154, 987–994. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.05.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H.; Yamaguchi T.; Kinoshita T.; Muromachi S. Gas separation of flue gas by tetra-n-butylammonium bromide hydrates under moderate pressure conditions. Energy 2017, 129, 292–298. 10.1016/j.energy.2017.04.074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takeya S.; Muromachi S.; Maekawa T.; Yamamoto Y.; Mimachi H.; Kinoshita T.; Murayama T.; Umeda H.; Ahn D.-H.; Iwasaki Y.; Hashimoto H.; Yamaguchi T.; Okaya K.; Matsuo S. Design of Ecological CO2 Enrichment System for Greenhouse Production using TBAB + CO2 Semi-Clathrate Hydrate. Energies 2017, 10, 927. 10.3390/en10070927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J.; Choi W.; Mok J.; Seo Y. Clathrate-Based CO2 Capture from CO2-Rich Natural Gas and Biogas. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 5627–5635. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b00712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMullan R.; Jeffrey G. A. Hydrates of the Tetra n-butyl and Tetra i-amyl Quaternary Ammonium Salts. J. Chem. Phys. 1959, 31, 1231–1234. 10.1063/1.1730574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson D. W.Clathrate hydrates. In Water A Comprehensive Treatise; Franks F., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, 1973; pp 115–234. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey G. A.Hydrate inclusion compounds. In Inclusion Compounds; Atwood J. L., Davies J. E. D., MacNicol D. D., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, 1984; pp 135–185. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama H. Solid-Liquid Phase Equilibria in the Symmetrical Tetraalkylammonium Halide-Water Systems. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1981, 54, 3717–3722. 10.1246/bcsj.54.3717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaponenko L. A.; Solodovnikov S. F.; Dyadin Y. A.; Aladko L. S.; Polyanskaya T. M. Crystallographic study of tetra-n-butylammonium bromide polyhydrates. J. Struct. Chem. 1984, 25, 157–159. 10.1007/bf00808575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyadin Y. A.; Udachin K. A. Clathrate polyhydrates of peralkylonium salts and their analogs. J. Struct. Chem. 1987, 28, 394–432. 10.1007/bf00753818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada W.; Shiro M.; Kondo H.; Takeya S.; Oyama H.; Ebinuma T.; Narita H. Tetra-n-butylammonium bromide–water (1/38). Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 2005, 61, o65–o66. 10.1107/s0108270104032743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionova T.; Komarov V.; Villevald G.; Aladko L.; Karpova T.; Manakov A. Calorimetric and Structural Studies of Tetrabutylammonium Chloride Ionic Clathrate Hydrates. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 11838–11846. 10.1021/jp103939q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto H.; Sato K.; Shiraiwa K.; Takeya S.; Nakajima M.; Ohmura R. Synthesis, characterization and thermal-property measurements of ionic semi-clathrate hydrates formed with tetrabutylphosphonium chloride and tetrabutylammonium acrylate. RSC Adv. 2011, 1, 315–322. 10.1039/c1ra00108f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muromachi S.; Takeya S.; Yamamoto Y.; Ohmura R. Characterization of tetra-n-butylphosphonium bromide semiclathrate hydrate by crystal structure analysis. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 2056–2060. 10.1039/c3ce41942h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama H. Hydrates of Organic Compounds. XI. Determination of the Melting Point and Hydration Numbers of the Clathrate-Like Hydrate of Tetrabutylammonium Chloride by Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1987, 60, 839–843. 10.1246/bcsj.60.839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama H.; Shimada W.; Ebinuma T.; Kamata Y.; Takeya S.; Uchida T.; Nagao J.; Narita H. Phase diagram, latent heat, and specific heat of TBAB semiclathrate hydrate crystals. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2005, 234, 131–135. 10.1016/j.fluid.2005.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi A. A.; Dolotko O.; Dalmazzone D. Hydrate phase equilibria data and hydrogen storage capacity measurement of the system H2 + tetrabutylammonium hydroxide + H2O. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2014, 361, 175–180. 10.1016/j.fluid.2013.10.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori T.; Muromachi S.; Yamasaki T.; Takeya S.; Yamamoto Y.; Alavi S.; Ohmura R. Phase Behavior and Structural Characterization of Ionic Clathrate Hydrate Formed with Tetra-n-butylphosphonium Hydroxide: Discovery of Primitive Crystal Structure. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 3862–3867. 10.1021/acs.cgd.5b00484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama H.; Watanabe K. Hydrates of Organic Compounds. III. The Formation of Clathrate-like Hydrates of Tetrabutylammonium Dicarboxylates. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1978, 51, 2518–2522. 10.1246/bcsj.51.2518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muromachi S.; Takeya S. Gas-containing semiclathrate hydrate formation by tetra-n-butylammonium carboxylates: Acrylate and butyrate. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2017, 441, 59–63. 10.1016/j.fluid.2017.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arai Y.; Yamauchi Y.; Tokutomi H.; Endo F.; Hotta A.; Alavi S.; Ohmura R. Thermophysical property measurements of tetrabutylphosphonium acetate (TBPAce) ionic semiclathrate hydrate as thermal energy storage medium for general air conditioning systems. Int. J. Refrig. 2018, 88, 102–107. 10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2017.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada J.; Shimada M.; Sugahara T.; Tsunashima K.; Tani A.; Tsuchida Y.; Matsumiya M. Phase Equilibrium Relations of Semiclathrate Hydrates Based on Tetra-n-butylphosphonium Formate, Acetate, and Lactate. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2018, 63, 3615–3620. 10.1021/acs.jced.8b00481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suginaka T.; Sakamoto H.; Iino K.; Takeya S.; Nakajima M.; Ohmura R. Thermodynamic properties of ionic semiclathrate hydrate formed with tetrabutylphosphonium bromide. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2012, 317, 25–28. 10.1016/j.fluid.2011.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye N.; Zhang P. Phase equilibrium and morphology characteristics of hydrates formed by tetra-n-butyl ammonium chloride and tetra-n-butyl phosphonium chloride with and without CO2. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2014, 361, 208–214. 10.1016/j.fluid.2013.10.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada W.; Ebinuma T.; Oyama H.; Kamata Y.; Takeya S.; Uchida T.; Nagao J.; Narita H. Separation of Gas Molecule Using Tetra-n-butyl Ammonium Bromide Semi-Clathrate Hydrate Crystals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 42, L129–L131. 10.1143/jjap.42.l129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chapoy A.; Anderson R.; Tohidi B. Low-Pressure Molecular Hydrogen Storage in Semi-clathrate Hydrates of Quaternary Ammonium Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 746–747. 10.1021/ja066883x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muromachi S.; Hashimoto H.; Maekawa T.; Takeya S.; Yamamoto Y. Phase equilibrium and characterization of ionic clathrate hydrates formed with tetra-n-butylammonium bromide and nitrogen gas. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2016, 413, 249–253. 10.1016/j.fluid.2015.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adisasmito S.; Frank R. J.; Sloan E. D. Hydrates of Carbon Dioxide and Methane Mixtures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1991, 36, 68–71. 10.1021/je00001a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sum A. K.; Burruss R. C.; Sloan E. D. Jr. Measurement of Clathrate Hydrates via Raman Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 7371–7377. 10.1021/jp970768e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mao W. L.; Mao H.-k.; Goncharov A. F.; Struzhkin V. V.; Guo Q.; Hu J.; Shu J.; Hemley R. J.; Somayazulu M.; Zhao Y. Hydrogen Clusters in Clathrate Hydrate. Science 2002, 297, 2247–2249. 10.1126/science.1075394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye N.; Zhang P. Equilibrium Data and Morphology of Tetra-n-butyl Ammonium Bromide Semiclathrate Hydrate with Carbon Dioxide. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2012, 57, 1557–1562. 10.1021/je3001443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S.; Li S.; Wang J.; Lang X.; Wang Y. Efficient Capture of CO2 from Simulated Flue Gas by Formation of TBAB or TBAF Semiclathrate Hydrates. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 4202–4208. 10.1021/ef9003329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Fan S.; Wang J.; Lang X.; Liang D. CO2 capture from binary mixture via forming hydrate with the help of tetra-n-butyl ammonium bromide. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 2009, 18, 15–20. 10.1016/s1003-9953(08)60085-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.-S.; Zhan H.; Xu C.-G.; Zeng Z.-Y.; Lv Q.-N.; Yan K.-F. Effects of Tetrabutyl-(ammonium/phosphonium) Salts on Clathrate Hydrate Capture of CO2 from Simulated Flue Gas. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 2518–2527. 10.1021/ef3000399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye N.; Zhang P. Phase Equilibrium Conditions and Carbon Dioxide Separation Efficiency of Tetra-n-butylphosphonium Bromide Hydrate. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2014, 59, 2920–2926. 10.1021/je500630r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H.; Yamaguchi T.; Ozeki H.; Muromachi S. Structure-driven CO2 selectivity and gas capacity of ionic clathrate hydrates. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17216. 10.1038/s41598-017-17375-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu H.; Maruyama K.; Yamagiwa K.; Tajima H. Separation processes for carbon dioxide capture with semi-clathrate hydrate slurry based on phase equilibria of CO2 + N2 + tetra-n-butylammonium bromide + water systems. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2019, 150, 289–298. 10.1016/j.cherd.2019.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro D. M.; Smit B.; Long J. R. Carbon dioxide capture: Prospects for new materials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6058–6082. 10.1002/anie.201000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu P.; Linga P.; Kumar R.; Englezos P. A review of the hydrate based gas separation (HBGS) process for carbon dioxide precombustion capture. Energy 2015, 85, 261–279. 10.1016/j.energy.2015.03.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z. W.; Zhang P.; Bao H. S.; Deng S. Review of fundamental properties of CO2 hydrates and CO2 capture and separation using hydration method. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 1273–1302. 10.1016/j.rser.2015.09.076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Choi S.-D.; Seo Y. CO2 capture from flue gas using clathrate formation in the presence of thermodynamic promoters. Energy 2017, 118, 950–956. 10.1016/j.energy.2016.10.122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muromachi S.; Udachin K. A.; Shin K.; Alavi S.; Moudrakovski I. L.; Ohmura R.; Ripmeester J. A. Guest-induced symmetry lowering of an ionic clathrate material for carbon capture. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11476–11479. 10.1039/c4cc02111h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muromachi S.; Udachin K. A.; Alavi S.; Ohmura R.; Ripmeester J. A. Selective occupancy of methane by cage symmetry in TBAB ionic clathrate hydrate. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 5621–5624. 10.1039/c6cc00264a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarov V. Y.; Rodionova T. V.; Terekhova I. S.; Kuratieva N. V. The Cubic Superstructure-I of Tetrabutylammonium Fluoride (C4H9)4NF·29.7H2O Clathrate Hydrate. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2007, 59, 11–15. 10.1007/s10847-006-9151-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuhara D.; Yasuoka K.; Takeya S.; Muromachi S. Anisotropy of dodecahedral water cages for guest gas occupancy in semiclathrate hydrates. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 10150–10153. 10.1039/c9cc05009d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyadin Y. A.; Terekhova I. S.; Polyanskaya T. M.; Aladko L. S. Clathrate hydrates of tetrabutylammonium fluoride and oxalate. J. Struct. Chem. 1977, 17, 566–571. 10.1007/bf00753438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto J.; Hashimoto S.; Tsuda T.; Sugahara T.; Inoue Y.; Ohgaki K. Thermodynamic and Raman spectroscopic studies on hydrogen+tetra-n-butyl ammonium fluoride semi-clathrate hydrates. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2008, 63, 5789–5794. 10.1016/j.ces.2008.08.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Fan S.; Wang J.; Lang X.; Wang Y. Semiclathrate Hydrate Phase Equilibria for CO2 in the Presence of Tetra-n-butyl Ammonium Halide (Bromide, Chloride, or Fluoride). J. Chem. Eng. Data 2010, 55, 3212–3215. 10.1021/je100059h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.; Lee Y.; Park S.; Kim Y.; Lee J. D.; Seo Y. Thermodynamic and Spectroscopic Identification of Guest Gas Enclathration in the Double Tetra-n-butylammonium Fluoride Semiclathrates. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 9075–9081. 10.1021/jp302647c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino T.; Yamamoto T.; Nagata K.; Sakamoto H.; Hashimoto S.; Sugahara T.; Ohgaki K. Thermodynamic Stabilities of Tetra-n-butyl Ammonium Chloride + H2, N2, CH4, CO2, or C2H6 Semiclathrate Hydrate Systems. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2010, 55, 839–841. 10.1021/je9004883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Lee S.; Lee Y.; Seo Y. CO2 Capture from Simulated Fuel Gas Mixtures Using Semiclathrate Hydrates Formed by Quaternary Ammonium Salts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7571–7577. 10.1021/es400966x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Zhang P.; Linga P. Semiclathrate hydrate process for pre-combustion capture of CO2 at near ambient temperatures. Appl. Energy 2017, 194, 267–278. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.10.118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leung D. Y. C.; Caramanna G.; Maroto-Valer M. M. An overview of current status of carbon dioxide capture and storage technologies. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 426–443. 10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMullan R. K.; Bonamico M.; Jeffrey G. A. Polyhedral Clathrate Hydrates. V. Structure of the Tetra-n-butyl Ammonium Fluoride Hydrate. J. Chem. Phys. 1963, 39, 3295–3310. 10.1063/1.1734193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.; Kida M.; Nagao J. Phase Transition of Tetra-n-butylammonium Bromide Hydrates Enclosing Krypton. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2016, 61, 679–685. 10.1021/acs.jced.5b00842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chazallon B.; Ziskind M.; Carpentier Y.; Focsa C. CO2 Capture Using Semi-Clathrates of Quaternary Ammonium Salt: Structure Change Induced by CO2 and N2 Enclathration. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 13440–13452. 10.1021/jp507789z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyanagi S.; Ohmura R. Crystal Growth of Ionic Semiclathrate Hydrate Formed in CO2 Gas + Tetrabutylammonium Bromide Aqueous Solution System. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 2087–2093. 10.1021/cg4001472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionova T. V.; Manakov A. Y.; Stenin Y. G.; Villevald G. V.; Karpova T. D. The heats of fusion of tetrabutylammonium fluoride ionic clathrate hydrates. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2008, 61, 107–111. 10.1007/s10847-007-9401-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J.; Xu C.-G.; Hu Y.-F.; Ding Y.-L.; Li X.-S. Phase equilibrium and Raman spectroscopic studies of semi-clathrate hydrates for methane, nitrogen and tetra-butyl-ammonium fluoride. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2016, 413, 48–52. 10.1016/j.fluid.2015.09.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muromachi S.; Yamamoto Y.; Takeya S. Bulk phase behavior of tetra-n-butylammonium bromide hydrates formed with carbon dioxide or methane gas. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 33, 1917–1921. 10.1007/s11814-016-0014-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon E. W.; Huber M. L.; McLinden M.. NIST Reference Fluid Thermodynamic and Transport Properties REFPROP, Ver. 9.1; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, 2013.

- Kunz O.; Wagner W. The GERG-2008 Wide-Range Equation of State for Natural Gases and Other Mixtures: An Expansion of GERG-2004. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2012, 57, 3032–3091. 10.1021/je300655b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muromachi S.; Shijima A.; Miyamoto H.; Ohmura R. Experimental measurements of carbon dioxide solubility in aqueous tetra-n-butylammonium bromide solutions. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2015, 85, 94–100. 10.1016/j.jct.2015.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schumpe A. The estimation of gas solubilities in salt solutions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1993, 48, 153–158. 10.1016/0009-2509(93)80291-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Phase annealing in SHELX-90: Direct methods for larger structures. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 1990, 46, 467–473. 10.1107/s0108767390000277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spek A. L. Structure validation in chemical crystallography. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2009, 65, 148–155. 10.1107/s090744490804362x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragoe N. PowderV2: a suite of applications for powder X-ray diffraction calculations. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2001, 34, 535. 10.1107/s0021889801006094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.