ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to demonstrate the potential of the systemic innovations approach for transforming transplantation systems. It explores potential leverage points for intervening in the LTx-system as well as possible paths of transformation. We present possible transition pathways giving the example of the German Lung transplantation system that teeters on the brink of collapse due to system failures and organ scarcity and illustrate systemic innovations as core mechanisms for systems change in health systems. Desk research and semi-structured experts interviews provided qualitative data for a deductive-inductive coding and a rigorous qualitative content analysis of the data. Depending on the systemic innovations chosen to achieve systems change, transplant systems follow different transformational paths: from a collapse to a leapfrogging towards a non-human transplantation system. Thus, global health areas like transplantation benefit from analysis on systemic innovations as these support researchers, public policy and regulators by developing transformative strategies in healthcare systems.

KEYWORDS: Systemic innovations, transplantations systems, transformations, lung allocation score, lung transplantation system, healthcare systems

1. Introduction

A transplantation scandal in 2012 in Germany and the subsequent loss of confidence in the system led to the lowest donation rate since 20 years, in spite of policy innovations in the legal transplantation act and public activities of the statutory health insurances. So far, those measures have not been powerful enough to transform the system in a way that would increase social acceptance, regain the willingness to donate renal organs and thus, increase transplantation rates.

Health care systems are complex adaptive systems (CAS) with many agents (patients, providers, insurances, government agencies, researchers) engaged in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment (Krubiner & Hyder, 2014; Rouse, 2008); Changing such a system requires a systemic approach, that is, any potential innovation needs to be analysed with respect to related requirements, impacts, and obstacles: Related innovations (RI) mean that in order to succeed, one focal innovation affects and is affected by (or even requires the invention of) a number of other innovations (Hauerwaas & Weisenfeld, 2017). Influencing each other and the whole system, RI are systemic innovations that generate system change (e.g., Mulgan, 2013). While approaches of systemic innovation increasingly gain attention for dealing with complex problems in social fields, it is surprising to find a lack of research on systemic innovations for transformation of Healthcare systems. Especially in the transplantation system where dramatic organ shortages require complex innovations for change and holistic decisions we find no studies exploring systemic innovations for transforming these systems.

This paper thus aims at 1) illustrating the impact of such related innovations as core mechanisms for system change in healthcare systems and applying this to the context of transplantation; 2) exploring and reflecting their potentials and limits for different transformational paths; and 3) extending the existing knowledge about systemic innovations and developing the approach further.

An in-depth analysis of the German lung transplantation system (LTx1) based on extensive desk research and interviews with experts shows that another set of RI could transform LTx and by extension other transplantation systems as they are in urgent need of system change. Systemic innovations are core mechanisms of change to address system weaknesses such as organ shortage and tissue rejections. The case of the German LTx system illustrates how systemic innovations establish a new path to deal with current problems of organ shortage and public mistrust: instead of continuing to wait for an increase of organ donation (as an existing path), the system evaded this core system malfunction by developing related innovations of organ allocation and organ preservation. The paper further acknowledges different leverages for system change and respective policy suggestions, which could enhance such transformation. Thus, the paper proposes the following contributions to the understanding of systems thinking for innovations and transformations:

Contribution to theory: The systemic innovation approach will be extended through linkage with the concepts of system thinking, CAS, mechanisms of systems change and respective leverage points required to intervene in systems;

Contribution to practice: The German LTx serves as an example for interrelated innovations for transformations and different transition paths. It thus derives recommendations for healthcare policy aiming at systems’ changes.

The case of Germany is transferrable to other transplantation and healthcare systems and maps two central problems: the lack of system thinking in both transplant researches and decision-making processes as well as a non-holistic, eclectic innovation management in healthcare.

The paper is organised as follows: chapter 2 provides the theoretical background and chapter 3 presents the methodology. Chapter 4 delivers the results of the German LTx case and chapter 5 draws conclusions.

2. Theoretical background

The theoretical background explains why system thinking on innovation and a systemic lens on transplantation as CAS could be a good viewpoint for policy and decision makers when reforming system’s structure. System thinking provides a lens to see synergies rather than single elements and to pay attention to system patterns (Daft, 2008) It developed as a field of inquiry and practice in the 20th century, and has multiple origins in different disciplines (Peters, 2014). Applied to the field of transplantation, it brings together innovation studies, transition approaches and systems science and creates a bridge between the holistic nature of innovations and the need of system change in transplantation.

2.1. Systems thinking for system change in transplantation

Systems thinking has been applied for addressing chronic transplantation systems failures (Braun, 1991; Braun & Joerges, 1993; Feuerstein, 1995; Joerges, 1996; Kang, Black Nembhard, Curry, Ghahramani, & Hwang, 2017; Machado, 1996/1998), thereby achieving contextualisation of the system and specifying system-environment relations. To understand system change through innovation, systemic thinking needs to be complemented with the CAS approach. A CAS is complex: it is a set of subsystems, which influence each other and interact with other parts of the system at different heterarchical levels of organisation and in a dynamic network, making a system’s behaviour unpredictable by the behaviour of its parts. A CAS is adaptive: it is able to learn from experience and to adapt itself to new conditions and to its environment. The core idea of CAS concerns its ability to adapt to and evolve in line with other systems and a changing environment (co-evolution) in reciprocal interaction. A CAS perspective helps to understand transplantation within its environment with regard to its adaptive capacity for self-organisation and thus, the levers for transition. It furthers the understanding of what systemic innovations in transplantation mean as they facilitate the system’s adaptive capacity: it relates the impact of an innovation aiming at improvement, change or creation with the impact of systems as a whole composed of several parts where this whole is more than simply the sum of the parts. Systemic innovations may consist of various types of innovations (Suurs & Roelof, 2014, p. 8) and may affect multiple parts of or even the entire system (Jaspers, 2009; Mäkimattila, 2014; Mulgan, 2013). Those types could be e.g. a new product, operation, process, strategy, new way of management (Hamel, 2008) or new institutions. System innovations might develop from one specific innovation through interdependences with other products, services etc. (Leadbeater, 2013). Table 1 summarises approaches to systemic innovations.

Table 1.

Some definitions of systemic innovations (based on Miller 2012 and Mäkimattila 2014).

| Definition of systemic innovation | Subcategories according to Miller 2012 |

|---|---|

| 1. A solution/catalyst/initiative designed and implemented to create systemic change | a solution/catalyst/initiative |

| |

| |

| |

| 2. Social technology built around systems phenomena | social technology built around |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| 3. Innovation created by a system | innovation created by |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| 4. A solution that is itself a system | a solution that is |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| 5. A multi-stage innovation process actively involving a whole system | a multi-stage innovation process actively involving |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| 6. An organisational, systems-thinking problem-solving process applied to broader social systems |

|

| |

| |

| |

| 7. An innovation process designed according to systems principles | an innovation process designed according to |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| 8. Systemic innovation as a process that results in the transformation of a system. | systemic innovation as a process that results in |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Subcategory of Mäkimatilla 2014 | |

| 9. Systemic innovations as structures & processes related activities which enable transformations of ideas into innovation (in a dynamic environment, having a feedback loop back to participating organisations) | Organising for systemic innovations as neither pure process nor pure outcome where their organisation is dependent on the core elements of |

| |

| |

|

2.2. Systemic innovations as mechanisms for change

Research on systemic innovations takes place mainly in two different fields: A first group of studies primarily deals with systemic innovations from an organisational (or business) perspective, applying systems thinking to organisations and innovation management (Chesbrough & Teece, 1996; Hauerwaas & Weisenfeld, 2017; Jaspers, 2009; Kaivo-oja, 2011; Mäkimattila, 2014; Maula, Keil, & Salmenkaita, 2006; Mortati, 2013; Taylor & Levitt, 2004).

The second group of studies applies systemic innovations in the context of sociotechnical change, transitions, and systems innovations (Davies et al., 2012; Elzen, Geels, & Green, 2004; Geels, 2004; Loorbach, 2007; Miller, 2012; Mortati, 2013; Mulgan & Leadbeater, 2013; Rotmans, Kemp, & van Asselt, 2001; Suurs & Roelofs, 2014). These studies provide ideas and guidelines for managing system change and for orchestrating a rough direction of systemic innovation. Despite different proceedings and strategies, these approaches deliver surprisingly similar views on possible transformational paths (Table 2)

Table 2.

Systemic innovations for systems change.

| Mulgan (2013) | Leadbeater (2013) | Transitions management | Dolata (2011) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System Change | A fully transformed system is usually characterised by the interplay of at least some of the following elements: New ideas, ways of thinking, skills or professions, changes in legislation, market metrics, measurement tools or power distribution, as well as the diffusion of technology and its development, are accelerators of change processes. Change coalitions and agencies play also a role in the development of the new. | A combination of the following elements is the composition of each system innovation: new products, services, technologies and new infrastructures that facilitate wide-spread availability. New alliances of partners bring together different elements and provide complementary services to achieve a common purpose. New consumer norms and behaviours go along with system innovation, emerging through social learning processes, peer-to-peer, copying and emulation. | System innovations/transitions are brought about by the dynamic interplay between different levels of the system. They are shifts from one sociotechnical system to another. System innovations are co-evolution processes, which involve technological changes, as well as changes in other elements. “Societal functions are fulfilled by sociotechnical systems, which consist of a cluster of elements, including technology, regulation, user practices and markets, cultural meaning, infrastructure, maintenance networks, and supply networks.” | Socio-technical changes as radical shifts which actually result from a variety of gradual transformations, influenced by related technological and socio-economic changes. The accumulated changes lead to substantial modifications within the “technological, institutional and (inter-) organisational foundations of a society, the economy or within a sector”. A gradual socio-technical transformation includes typical modes which are involved, such as layering, conversion, displacement, drift and exhaustion. Specific combinations of those modes characterise different variants of gradual transformation as they interlock and mix in specific ways in the periods of change. | ||

| Geels (2002) | Geels & Schot (2007) | Kemp & Rip (2001) | ||||

|

Multilevel Perspective Sociotechnical systems are analysed through a multilevel perspective and consist of technological niches (micro level), sociotechnical regimes (meso level), and slowly changing “no simple causality in system innovations, but ‘processes at multiple dimensions and levels simultaneously’”. |

Transition Pathways Transition pathways as interaction patterns between levels. |

Niche management (SNM) The aim of strategic niche management (SNM) is to plan and provide protected spaces as a chance for new technology to develop and grow into its actual usability. |

||||

| Core Elements |

Six Steps for System Change 1. Mapping systems to build up their dynamics 2. Analysing what prompts change/what makes systemic innovations possible 3. Being aware of different rhythms of systemic change 4. Identifying the role of the systems‘ innovators 5. Scrutinising proposals and testing out emerging systems 6. Action-taking by the individual or the organisation |

Four Strategies for System Change 1. Drive 2. Repurpose 3. Reconfigure . Leapfrog |

Four Phases of Transition/System Change 1. Emergence of niche-innovation 2. Usage in small market niches 3. “Breakthrough of the new technology, wide diffusion and competition with the established regime” 4. “New technology replaces the old regime” |

Four Pathways 1. Transformation 2. Technological substitution 3. Reconfiguration 4. De-alignment and re-alignment |

Five Steps of SNM 1. Choice of technology 2. Selection of the experiment 3. Experiment set-up 4. Upscaling of the experiment by means of policy 5. Breakdown of protection |

Variants of Gradual Transformation 1. Dynamic reproduction and incremental change 2. Substantial realignment and architectural change 3. Disruption, erosion and substitutive change 4. Enduring coexistence, substitutive or architectural change |

The systemic innovations are mechanisms of change that operate through feedback loops (Meadows, 2008), promoting or preventing systems change and they are crucial elements of transformation. Balancing (negative) feedbacks are equilibrating mechanisms maintaining the stability of the system. Reinforcing (positive) feedback loops apply their own momentum to drive the system increasingly towards the direction where it is already running to. Through vicious and virtuous cycles, they are reinforcing, amplifying, snowballing mechanisms leading to exponential growth or to runaway collapse over time (ibid., p. 189).

2.3. Leverages for transformation in the German transplantation system

Meadows (1999) differentiates between low and high leverage points as places in systems where the smallest shift could lead to fundamental changes in the whole system. Low leverage points such as standards, taxes, subsidies or buffers in the material structure of the system lead to small changes whereas high leverage points like introducing new goals, changing the system’s structure, or a paradigm shift cause large changes in a system. Determining leverage points could offer answers to the question, where to interfere in the transplantation system to change its overall behaviour.

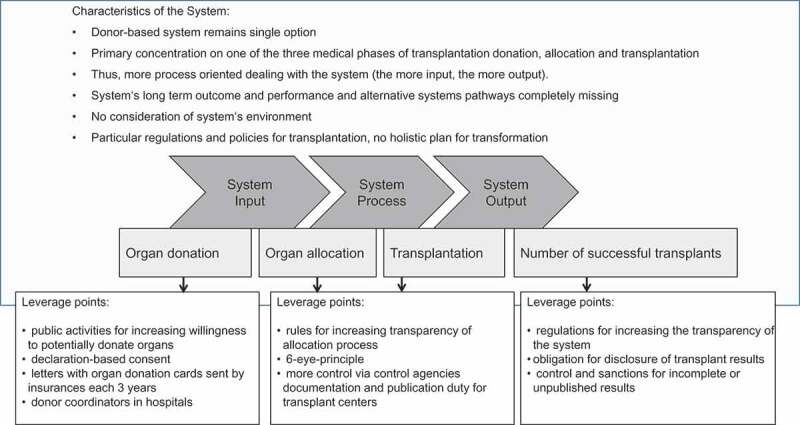

In Germany and beyond, changes in the transplantation system are associated with low leverages (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Current thinking for transplantation systems and respective interventions in the system (leverages).

These changes concerned highly tangible, but basically weak leverage points like the “decision” regulation of declaration-based consent or transparency-driven control rules and the six-eyes principle of score evaluation. All these low-level leverages in Germany failed to address the biggest challenges for an increase in organ transplantations. The challenges encompass several institutional dimensions of the environment: starting with the still dominant decision making by relatives (and not the organ donation disposition of one’s own) to the key role of physicians and of the system’s structure in general – all of them radically influencing the individual decision level and requiring interventions at higher leverage points.

Similar to other German transplant systems the LTx struggles not only with some medical challenges (e.g. suboptimal management of organ rejection and infections) but mostly with too few lung donors. The organ shortage was countered by implementing several interlinked innovations at different leverage points in the system. These leverages for transformations as described later in the Case of the German Lung TX system can be empirically assessed and can help decision makers to develop a system’s transitions pathways.

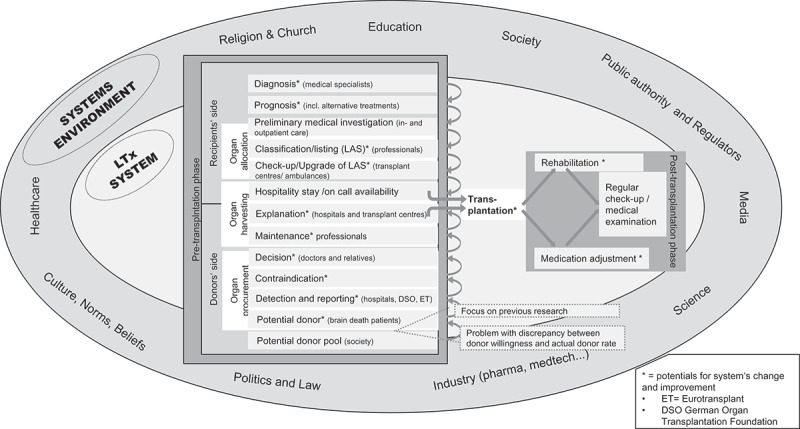

2.4. The case of the German LTx system

LTx is often the last chance to prolong and dramatically improve the quality of life for people with severe end-stage pulmonary diseases,2 where alternative treatment options have already been or would be unusable. Similar to other transplant systems, the LTx System is a CAS consisting of 1) organ procurement (including donation as the current system’s input from the environment), 2) organ distribution (including allocation and harvesting as a throughput), 3) transplantation (as a surgical and technological process) and 4) post-transplantation (including control of the transplants as an output back to the environment). As a complex adaptive transplant system it is strongly embedded in its environment of physicians, pharma and medical industry, small hospitals, mass media, patients, relatives of potential donors, regulators and society etc. The elements of the system are also part of other systems like healthcare delivery, medical education, policy etc., which is crucial for understanding how transformations occur. Accordingly, the LTx is a very complex, heteriarchical and multi-actor system which always needs to be perceived as embedded in this certain environment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The German lung transplantation system.

It is therefore surprising that current research (reviews e.g. by Gold, K-H, & Koch, 2001; Irving et al., 2012; Keller et al., 2004; Schulz, Gold, Knesebeck, & Koch, 2002; Wakefield, 2010) focuses predominantly on the system’s element of organ donation: more precisely on individual organ donation willingness and respective efforts to increase this as well as on bridging the gap between willingness and actual donation. In doing so, many studies and most political and social efforts regarding transplantation often do not deal with transforming the “whole” and its malfunctions but rather with maintaining the existing system of organ donation. As the review study of Gold et al. (2001) indicated much earlier, the German process of donation can benefit from diverse places to intervene in the whole transplant system and in its environment (e.g. structural systems improvements, educational and training interventions, innovative facilities and better design of the situational framework). The following analysis of the system is less based on the four core areas of transplantation, but rather shows how interwoven the areas are with the environment and how the CAS nature of transplantation sets leverage points outside the “input-through-output” system. There, systemic innovations have already been important for the development of transplantations: the invention of the heart-lung machine and new immunosuppressive drugs in the 1960s made other innovations in the surgery and technological field more successful and enforced the development of all subsystems of transplantation like heart, kidney, lung etc. The emergence of the immunosuppressant cyclosporine in the 1980s “moved lung transplant beyond experimental medicine into mainstream therapy” (Colvin-Adams et al., 2012, p. 3213) and speeded up the innovation process of LTx. Since then, it took (only) 20 years for LTx to become an established treatment option in highly specialised centres and an effective method of surviving several years and living a worth life.

We thus assume that a next set of related innovations as a new systemic innovation could serve again as a key instrument to transform not only LTx but rather all transplantation systems.

In order to identify such systemic innovation and take a deeper look on interlinked effects and possible transformational paths, a single case analysis of this German LTx system was the appropriate research method.

3. Methods

3.1. A qualitative design: the case of the German LTx

We chose the LTx system as a single case of transplantation systems to expand the theoretical base of the systemic innovation approach: Such an in-depth single case study enables uncovering areas for research and theory development (Voss, Tsikriktsis, & Frohlich, 2002). The analysis of the LTx addresses questions such as “why and how” in situations where the researchers have no control over the events while attempting to deeply understand, systematise, and analyse the facts (Yin, 2013).

3.2. Data generation

The methodology of generation of data began first with a systematic desk research gaining information about the following themes:

LTx system

Innovations in lung transplantation

Lung Allocation Score (LAS)

Transplantation systems

Regulation/Law/Policy of (Lung) Transplantation in Germany

We then generated deductive coding that provided the basis for the expert interviews. Semi-structured expert interviews were conducted because of their comparability and the smaller predetermination by the interviewer (Lamnek, 2005). The deductive coding frame provided six main categories which delivered the question blocks for conducting the semi-structured questionnaire:

Influences from LAS on the system and vice versa, influences on LAS

Main formal and informal institutions (rules, norms, laws, behaviours, culture)

Systemic innovations: the interrelation of concrete innovations (already identified in desk research) to LAS and impact on the system

Personal assumption of experts as forecasting of future systems development

Personal assumption of experts’ requirements on the current system (status quo)

Some specifically tailored (for the respective expert’s knowledge) questions regarding innovations or systems

The experts were chosen on the basis of their publications and their (internationally) recognised expertise in the field of German transplantation system, lung transplants and LAS (see detailed experts information in Appendix II). Telephone interviews were conducted due to the exclusivity of the number of eligible experts with an extremely work-filled and busy schedule in this area. The Germany-wide interview requests of 18 experts in total, with the option of flexible days/hours had a high response rate of 45%. Eight expert interviews (period 2014–2015) were conducted with core actors of the lung transplant system and innovators implementing the LAS. A pre-test phase with five interviews served as a basis for questionnaire modifications. As the experts are operating in different fields of the system, some questions were slightly modified for each interview.

3.3. Data analysis

Both, the questionnaire and the actual interviews were performed and transcribed in German (and later translated in English), following the transcription rules by Kuckartz, Dresing, Rädiker, and Stefer (2008). The transcription was then uploaded into the software MAXQDA and processed in an iterative qualitative content analysis. The construction of the exploration guide as well as the resulting qualitative data evaluation and the coding process follow the iterative qualitative methodology of Schreier (2012) and Kuckartz (2014) with a combination of deductive (concept-driven) and inductive (material-based) data gathering and analysis. Thus, the guide did not set a fixed schedule but collects data in similar range of categories by more open, clear, neutral and non-suggestive questions (Lamnek, 2005, p. 352). The CQA enables in a flexible and systematic way the reduction of data by assigning successive parts of material to the categories of the coding frame which is the core element of the method featuring the description and interpretation of the material (Schreier, 2012, p. 170). The inductive coding was developed in an iterative process based on the already mentioned deductive categories (1) to (6) and the interview material. It then explored further the coding framework which was double-coded and finally modified. 445 codes in total were aggregated and served as basis for building the results and their later structuration (Table 3).

Table 3.

The deductive-inductive mix coding of systemic innovations in the German LTx system.

| Code-system | 445 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal and informal institutions | 10 | |||

| Control mechanisms | 3 | |||

| 6-eye-principle | 1 | |||

| Data management/AQUA/STäKo | 16 | |||

| Target agreement | 1 | |||

| Structured dialogue | 3 | |||

| Rules as game changer | 3 | |||

| The role of professionals | 5 | |||

| HTA | 2 | |||

| Policy issues | 8 | |||

| Interaction with system’s environment | 10 | |||

| Information | 11 | |||

| Satisfaction with LAS | 12 | |||

| The actors – type, organisation, networks | 14 | |||

| Barriers | 17 | |||

| Specific expert knowledge | 0 | |||

| Innovation’s/pioneer’s power | 18 | |||

| Recent system: expert requirements (as leverages) | 4 | |||

| New sanctions mechanisms | 2 | |||

| Changes in numbers of centres | 3 | |||

| Opt-out policy | 1 | |||

| Individualisation of LAS | 1 | |||

| Holistic view on transplant systems | 6 | |||

| Transplant coordinator | 1 | |||

| DSO delegation of competences | 3 | |||

| Donor-centre-relation | 2 | |||

| Centralisation of the transplantation structure | 2 | |||

| Change in structure of donor’s registration | 1 | |||

| Related systemic innovations | 10 | |||

| Transplant register | 3 | |||

| Artificial lungs/bridging/pre LAS phase | 22 | |||

| Incremental innovations/improvements | 4 | |||

| Committee | 14 | |||

| LAS+ | 3 | |||

| Expansion of inclusion criteria | 4 | |||

| Mini-match | 11 | |||

| Rescue allocation | 19 | |||

| ECD | 5 | |||

| Organ Care System TM etc. | 8 | |||

| Ex vivo lung perfusion | 9 | |||

| Disruptive innovations | 11 | |||

| Immunological innovations | 2 | |||

| New drugs/programmes prolonging patient’s life | 3 | |||

| LAS influenced by TXsystem | 0 | |||

| LAS as a CAS | 16 | |||

| Weakness of LAS | 14 | |||

| Obstacles of introduction | 8 | |||

| Inadequate transfer of seldom indicators | 12 | |||

| Via systemic innovation | 6 | |||

| LAS influence on TXsystem | 9 | |||

| Less hospitalisation | 4 | |||

| Information source for colleagues | 2 | |||

| Organisational changes | 6 | |||

| More ambulatory care | 1 | |||

| Bureaucracy/more workload | 8 | |||

| Less non-active/nominal members | 3 | |||

| Less “accommodation” patients | 4 | |||

| Transitions | 2 | |||

| Crisis as a starting point | 3 | |||

| Feedback loops | 9 | |||

| Better system’s quality | 6 | |||

| More objectivity/transparency | 10 | |||

| More transplantations | 4 | |||

| Better/remaining transplant results | 5 | |||

| Less waiting time | 6 | |||

| Less mortality on waiting list | 3 | |||

| Patient management innovation | 8 | |||

| Evaluation process innovation | 8 |

CQA has three core characteristics – it is systematic, rules-guided and oriented on the quality criteria of validity and reliability (Schreier, 2014).

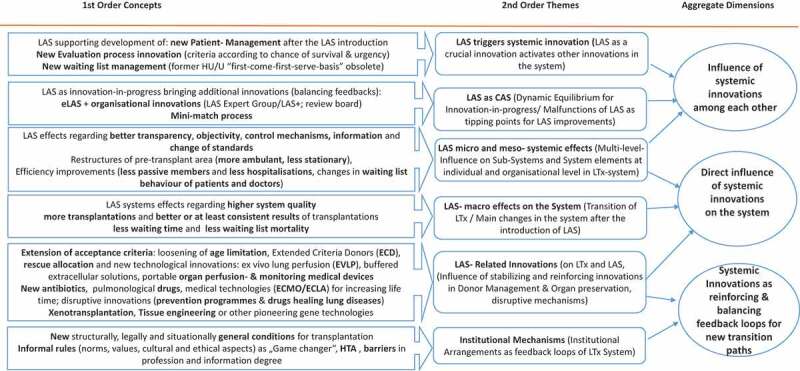

To provide additional rigidity a proceeding used by Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (2013) was used for simplification, visualisation and more abstract structuration of the results enabling an aggregated and verifiable view on the qualitative data: first order codes are combined to second order themes and aggregate dimension (Figure 3). All insights presented in the next section are derived deductively and inductively from the qualitative data and follow the structure of the second order themes. Data generated from the interviews, which provide central results, are additionally visualised in charts containing crucial semi-anonymised quotes of the experts (see all charts in Appendix I).

Figure 3.

Visualisation of results (based on the data structuration of Gioia et al., 2013).

4. Results: systemic innovations and their impacts in the German LTx system

Following the structuration of results (Gioia et al., 2013, Figure 3), we first describe the influence of the related innovations on each other (4.1, 4.2, 4.3), explain then the influence of systemic innovations on the system (4.3., 4.4 and 4.5) and finally (4.5 and 4.6) present systemic innovations as feedback loops required for new transformational paths.

4.1. LAS triggers systemic innovation

LAS arose from the system’s problem of poor organ donation and was introduced in the United States in 2005 and adapted in Germany in December 2011. It bears the idea of “right” and fair process for allocating the limited number of available lungs. As a new allocation process involving a scoring system to help determine the recipient’s position on the waiting list for lung transplantation, the LAS aims to find the recipient with the highest benefit and presumably longest possible survival term from lung transplantation. This addressed in a second step successive malfunctions in organ allocation such as preventive listing and hospitalisation for gaining waiting time because of waiting time-based allocation (first-come-first-serve-principle) or misbehaviours of transplant professionals, who strive for getting “a slice of the limited supply”. In a balancing feedback loop, a new, “fairer” allocation system was to be ensured by the indicators of pro-operative urgency and post-transplant benefit from the organ and thus developed as

The LAS-introduction had multiple effects on the German LTx system. First, the previous allocation process, based on the international High Urgent (HU) and Urgent (U) status, ceased to exist for lung transplant candidates, they were all downgraded to the elective status (T), the former HU and U criteria have become obsolete and the first-come-first-serve-basis of decisions was ousted. The new allocation process allows each lung transplant candidate at age 12+ to get an individualised lung allocation score, which determinates the priority for receiving a lung transplant when a donor lung becomes available (an adjusted scale from 0 to 100, with 0 = healthy and 100 = extremely sick). It calculates score points using parameters from a couple of diversely valuated pre-transplantational clinical diagnostic data (e.g. height, weight, lung diagnosis, supplemental oxygen requirement, 6-minute walk distance etc.) and serology, tissue type, actual heart and lung condition etc. as well as the presumed survival term before and after transplantation (detailed in Gottlieb et al., 2017). LAS thereby triggered a new waiting list management in the groups of patients, professionals and medical staff: the transplant centres, which ascertain the medical and social parameters for listing as well as the potential receivers themselves, receive some new and from the HU-list adapted factors which are to be evaluated. Once determined, the matching data underlies a new calculation and new restrictions for the waiting list. The recipients must evaluate their LAS periodically; the timeframe depends on their actual health condition (between 90 and 14 days). The transplant centres and pre-transplant ambulances which have no decision power about the time when their own patients would get a suitable organ, transmit all the new information regarding potential recipients to Eurotransplant (ET), which is responsible for the organ allocation in Germany and seven3 other member countries and generates a match list for each donor organ.

4.2. LAS as CAS

Since different diseases need different parameters regarding e.g., the suffering level, progression speed, and compliance, the current calculation of the LAS requests further adjustments. Therefore, the LAS is an innovation in progress (in terms of CAS it is continuously adapting and coevolving) and its problems require additional innovations. A core weakness of LAS since its introduction is the standardisation of some disease-specifics and their inadequate implementation into the score calculation: as the score generalises core parameters into numbers, the individual situation of particular patients and/or the complexity of specific diseases cannot be realistically reflected and the scores may be relatively low. This malfunction (see Chart 1 in the appendix) of LAS led to diverse effects: Disease groups could be sorted in “winners and losers” of the LAS-introduction, the profile of transplant recipients changed from more lung emphysema patients to more patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and waiting list mortality was reduced.

As the analysis of the expert interviews indicates (Chart 2), this weakness of the LAS-system has diverse implications for the development of LAS improvements (LAS+) and systemic innovations related to the LAS.

Two organisational novelties resulted from this LAS weakness: (1) A Review Board was set up to evaluate exceptional LAS (eLAS) for patients, where the calculated LAS is seen as not adequately reflecting the urgency and expected outcome. (2) An expert group deals with the LAS improvement by revising and complementing the current LAS-parameters. This expert group currently develops a readjusted LAS to develop the LAS further.

4.3. LAS micro – and meso systemic effects

Standardising criteria and their calculation increases transparency of lung allocation in Germany, which the experts perceive as a positive effect of the LAS-introduction (Chart 3).

Moreover, due to the fact that the scoring can be retraced by everybody (each patient, physician, medical staff and control authorities can review how the scoring points were calculated), the LAS is supposed to be “safer” and not as prone to manipulations as other scores. This in turn has a macro-level impact on the system’s quality and on informal changes like public trust or professionals’ behaviour.

The LAS thus not only led to an adjustment of the evaluation process but also changed existing working routines (organisational changes) and the doctor-patient-relationship (patient management changes). Both, patients and medics now have to regularly invest time for evaluating LAS and thus, to keep in touch. This frequent contact has important system improvement effects: For transplant centres the level of information and the quality of patient monitoring can rise, new or additional diseases and physical complaints can be identified in time; the progression of diseases or sudden health deterioration can be recognised early and implemented in the next LAS evaluation. As the experts point out (Chart 4), changes in LAS serve at the individual level as information sources for the centres’ doctors (regarding the imminent timing of transplantation), physicians (regarding the patient’s urgency and a respective rapid referral to the transplant centre), and patients (increasing their compliance and awareness of their disease).

On the organisational level, different effects after LAS introduction evolved and lead to more effective working structures (Chart 5). The (only) negative effect mentioned was an initial increase of workflow for hospital staff, resulting from new rules for data evaluation and the rising number of transplantations. However, this aspect seems to have recently become an improved daily routine. Diverse other changes after LAS-introduction have significantly improved the daily work and the work structure of different actors. According to the experts, there is a clear decrease of “preventive” hospitalisation and nominal members of the waiting list and a restructuring of the pre-transplant area from more ambulatory and less stationary care. The frequency of the new score evaluation and of face-to-face connection enabled medics to implement better waiting list- and patient management and thus to make LAS much more effective. All listed patients, who are LAS-evaluated and correspond with their values in the range 0–100 are de facto transplant candidates awaiting lung donation. Accordingly, waiting time is no more a major criterion for scoring. The “accommodation” of patients in the hospitals loses attractiveness and leads to fewer hospitalisations with financial advantage for the hospital and patients’ advantage of staying at home.

4.4. LAS- macro effects on the system level

From the macro perspective of system transition, the adjusted list reflects the actual quantity of lungs needed. In their study, Valapour et al. (2015) describe for the USA a steady growth of active patients on the waiting list after the LAS introduction and a clear decrease of inactive candidates that reached an all-time low in 2013. As hoped, in the USA the LAS introduction was also associated with an increasing number of lung transplants performed each year, reduction in waiting time and waiting list mortality rate, whereas survival after transplant has remained relatively unchanged compared with outcomes in the pre-LAS era (Yusen & Lederer, 2013).

The years of 2012 until 2016 provide reliable data about such effects for Germany (Gottlieb et al., 2017). Experts mentioned (Chart 6) as main system changes the reduced waiting time and mortality on the waiting list while transplant results remained stable or even improved. Moreover, as already described, the transparency of score evaluation improved the quality of the system.

4.5. LAS- related innovation

The growth in LTx rate is related not solely to LAS but rather to an interplay with additional innovations in donor management and new life-prolonging technologies. The joint effect of all these activities caused a systemic change. Depending on how radical those innovations are and how strongly they affect the direction of transforming the system, they support, hinder or even destroy the existing LTx system (the latter being disruptive innovations, Christensen, 1997).

4.5.1. Related innovations with a direct relationship

Related innovations like life-prolonging new drugs and treatments can have a bridging function for recipients on the waiting list until a suitable lung is found, or even substitute the transplantation and thus become a new therapy option (as disruptive innovations). This may support the current system by temporarily relieving the pressure to find lungs or even reduce the need for new lungs via parallel therapy solutions. An example for the first kind of relation are new antibiotics, pulmonary drugs and medical technologies like new generations “artificial lungs” which get a grip on infections or on lung failures that cause complications and increased mortality on the waiting list.

Especially the incremental advances in Extracorporeal Life Support devices (ECLS) beyond the LAS-introduction, like the “awake ECMO” (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for awake non-intubated patients) and similar technologies (e.g. the Extracorporeal Lung assist, ECLA) for bridging the recipient until transplantation, are strongly interrelated with the functioning of the LAS. Their use increased after the LAS-introduction (Gottlieb et al., 2014, 2017) for highly sick patients who otherwise would not survive until a suitable lung is donated. As the experts explained (Chart 7), using ECMO-devices does not automatically mean calculating additional LAS points since the use of extracorporeal support is not directly incorporated in the LAS. But the acute deterioration in the health status of the patient using the devices leads certainly to higher LAS in a next step. If the technologies continue to improve and reach the state of a solid, less-invasive and less risky therapy or even become a temporary optional therapy (e.g. bio-artificial lung), the LAS will need some further revision regarding the scoring point for usage of such devices. However, currently, it is still only used in precarious cases for high urgent patients as a last option and thus, a high LAS-score by ECLA/ECMO reflects this adequately.

4.5.2. Related innovations as disruptive mechanisms

Disruptive innovations are strategies that can reduce the need for transplantation or supersede the current transplantation system. Examples are prevention programs for smoking as a major cause of end-stage lung disease from COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and pharmacological treatments and drugs like ivacaftor (trade name Kalydeco®), introduced for Cystic Fibrosis which “repairs” the genetic-defect in specific gene-mutations, thereby allowing a “normal” live while evading an end-stage treatment via transplantation. Such medications are already leading to a decrease in listing for transplantation by pulmonary hypertension (PH) accounting for about 5% of LTx activity (Gottlieb et al., 2014).

Further disruptive RI could arise from longed-for results of xenotransplantation, tissue engineering or other breakthrough gene technologies, which could make the donation of human organs obsolete. Those solutions would create totally new conditions and requirements for transplant “supply” and thus, would radically transform the system. According to the experts (Chart 8) the realisation of these innovations will take years. However, their potential to disrupt the existing (human donors-based) paths in transplantation (for the lung especially those of xenotransplants) should be considered much stronger. They would lead to a readjustment of LAS regarding urgency-related and immunological parameters. Immunology is a central mechanism for changing transplant rates and success on both sides – donor and recipient. Currently, attempts are made in exploring innovations in genetic MICA-variation between donors and recipient and the development of respective tests (IdW, 2017). Furthermore, the CRISPR-CAS9 technology applied for xeno-generation of transplantable human tissues will further enhance the exploration of this disruptive transition path (Wu et al., 2017). Hence, innovations in immunology and organ rejection are expected to deliver major contributions to the LTx system in the next years.

4.5.3. Related innovations in donor management

The LTx system tried to compensate the lack of organs by expanding the existing donor pool via systemic innovations. Since in the ET area only ca. 20% of all donors have suitable lungs for transplantation while the demand of lungs for transplantation increases, efforts were made to save as many as possible of the very few approved organs and thus, to transplant all available organs – even the suboptimal ones.

The expansion of inclusion criteria and relaxation of the age limit for lung donation is a kind of donor management innovation which has resulted from the substantial increase of the waiting list (Valapour et al., 2013) and tried to improve the utilisation of organs using interrelated allocation systems of lung donor selection and management. Such strategies to overcome the insufficient lung donation have already been explored successfully in the last decade, e.g. living donor lobar, split lung transplantations, the procedure of downsizing donor lungs in case of size discrepancy or the extension of donor age (van Raemdonck et al., 2009). Extended criteria donors (ECD), or “marginal donors” (van Raemdonck et al., 2009), means a deviation from ideal donor criteria. Several feedback loops in the systems of donation (rising age of donors due to lack of donors), of allocation (shift in organ recipient demographic after LAS introduction) and of transplantation (implementing new technologies for improvement of marginal organs) accelerated the development of ECD and led to further related systemic innovations in LTx. E.g., the ECD are strongly interrelated with the rescue allocation (RA) which aims to find suitable recipients primarily for the ECD organs and hence, to avoid the loss of those organs (Smits, van der Bij, & Rahmel, 2009, p. 94; see also experts results in Chart 9).

This RA is envisioned when an organ is not accepted via regular LAS allocation because of medical or logistical4 reasons. RA has a strong reciprocal interrelation with the LAS: as a patient-oriented allocation system, the LAS rank-position on the waiting list is determined by the match criteria. If the offered lung has been rejected by at least three centres, the lung is considered to be an ECD lung and the patient-oriented allocation can be switched to a centre (Smits et al., 2011), which then can select any listed recipient from their local waiting list (Smits et al., 2009, p. 94). Over the last five years, an “undesired trend” (ET, 2013) has developed in Germany: more than 30% of all lung transplants are performed via RA. This trend results in patients with lower LAS (seemed to be stable enough for ECD lungs) or with a certain disease being systematically selected into the rescue allocation [ibid., (Chart 10)].

Hence, the CAS nature of LAS could enhance acceptance of ECD and RA while impeding proper LAS-allocation. Even though recent studies (Gottlieb et al., 2014; Sommer et al., 2013a) show, that RA donor lungs for stable recipients lead to very good overall survival, a high RA rate may indicate an important system problem. Since it is used to allocate the available lungs beyond the LAS, it could undermine the prime idea of LAS of patient-oriented criteria-matched allocation and thus, increasing RA should not become rife.

This reciprocal and reinforcing interrelation of RA and LAS gave rise to an innovation that aims at bringing RA and LAS together, thereby improving the LAS further (Chart 11): since December 2013 the recipient-oriented Extended Allocation (EA) is such an innovation allocating the “rescue” lungs in an accelerated LAS-RA-mixture-procedure offered as Mini-Match-process, where all transplant centres receive the rescue offer and can propose up to two preferred patients while ET allocates the lung for the one with the highest LAS within the nominated group. Such a Mini-Match is expected to increase the beneficial influence of the LAS on waiting list mortality in Germany (Gottlieb et al., 2014, p.1326). Mini-Match has not replaced the former (competitive) RA, rather, in order to avoid the loss of the organ both, Mini-Match and competitive RA are still options. As the expert results (Chart 12) indicate, while the idea of the Mini-Match-procedure is welcomed within the expert’s field, the type of RA is not always clear. Thus, the effectiveness of the new process needs further analysis. According to the experts and publications. (e.g. ET, 2014a, 2014b, p. 26). The aim of this extended allocation is to increase the transparency of allocation as well as the number of allocations made via LAS (recipient-oriented). In a reinforcing feedback loop, two additional effects can persist: decline in the centre-oriented “competitive rescue” RA as well as more effective evaluation and completion of transplant data and thus, a better validation of the LAS (since the RA-patients are above 30 % and are currently not undergoing the allocation via LAS, their success rates are not at disposal for its evaluation).

4.5.4. Related innovations in lung preservation

Donor lungs are most often rejected for poor oxygenation, purulent secretions, and/or radiographic opacities (Cahill, Raman, Selzman, & Liou, 2013). Yet the reasons why patient survival rate after lung transplantation is lower compared to other solid transplant organs are multifactorial in nature. Suboptimal lung preservation and subsequent ischemia-reperfusion injury sustained by the donor lung play crucial roles for these failures. The use of donor lungs with suboptimal oxygenation as well as the current standard of cold storage of lungs are associated with a negative effect on post-transplant survival (Thabut et al., 2005a, 2005b). Therefore, new methods of donor preservation and ventilation try to overcome these issues by using the method of warm preservation (ex vivo lung perfusion EVLP). That relational process innovation has been developed as a tool to assess and also potentially repair lungs before transplantation (Mariscal, Cypel, & Keshavjee, 2017). EVLP allows for better assessment and preservation of donated lungs as well as for repair and conditioning of lungs previously unsuitable, and it makes them safe for transplant. The interrelation with the portable organ perfusion and monitoring medical device5 intensifies the future impact of the ex vivo technology and may improve donor lung assessment and management. It keeps donor lungs functioning and “breathing” in a near-physiological ventilated and perfused state outside the body during transport. Though the application of EVLP in Germany is still not a standard especially for suboptimal lungs, the mobile device takes increasingly place for the storage of donated lungs. Two possible interrelations could emerge regarding LAS: as EVLP happens after LAS, in the next step after allocation, it could support the outcome of transplantation and thus increase the prospect of success. At the same time, it would be related to RA of suboptimal organs and could increase the parallel usage of Mini-Match-allocation (EA), while hindering the institutionalisation of LAS as the main allocation path.

4.6. Institutional mechanisms

For a transformation of the system, new formal (e.g. regulation, law) and informal (e.g. values, norms) institutions are required, since they serve as additional leverage points.

The new formal institutional changes in transplant law introduced as balancing loops trying to maintain the system’s functioning in 2012 (supplemented in 2013 and 2016) were a reaction to informal settings like low donation rate, public mistrust and unwillingness to donate. Other new institutions were implemented to fulfil formal rules like the transposition of EU legislation (2010/45/EU) into national law. Core interventions were:

Improvement and further development of control feedback mechanisms, e.g. a legal framework for audits and inspections in transplantation centres and organ removal-hospitals, introduction of the examination and surveillance committees.

The introduction of a donor coordination/transplantation commissary in organ removal hospitals.

The establishment of a national transplant register as an important prerequisite for the development of a fair allocation process.

A declaration-based solution applied from November 2012 including health insurers contacting regularly their clients aged 16+ to encourage and document decisions about organ donation.

One positive system effect of the formal interventions in 2012 was the improvement of data quality and thus, better control and transparency. In this context the introduction of a transplant register supports the data quality and thus the transparency and quality of LTx (and other German transplantation systems). However, a major problem of the new formal institutional arrangements in Germany is the lack of holistic consideration of their effects. The new formal political regulations from 2012 have an ambivalent effect on the LTx system. On the one hand, the regulations of quality and control mechanisms seem to improve LTx practices and thus, could have a positive impact on formal and informal issues in the long term: e.g. better transparency ensures that agreed rules are correctly implemented and that the system is better protected against manipulations. The system’s increased safety could thus increase perceived objectivity and trust. The “positive” or pro-organ-donation formulation in §1 of the transplant law (“The aim of the law is to encourage the willingness to donate in Germany”) can be interpreted as the intention of the state to increase organ donation, rather than a neutral declaration and therefore seems to intensify scepticism and lower willingness to donate rather than remedying them. The second weakness of the law is the regularity of unsolicited sending of information leaflets by the health insurance companies, which could be perceived as too intrusive and thus, could enhance scepticism. The declaration-based decision is hence a balancing feedback loop continuing the existing (formal and informal) institutional path of the opt-in consent in Germany. Although many experts recommend the introduction of the formal opt-out rules for overcoming the lock-in in this institutional path, given the strong influence of informal and historical dependencies in Germany, it could be in doubt that this formal institutional change alone would lead to a transformation. Moreover, as Shepherd, O’Carroll, and Ferguson (2014) reviewed in their panel study of opt-in and opt-out-consent’s regulation in 48 countries, for lungs no differences between opt-out and opt-in regarding the number of transplants can be found. The authors point to multiple, informal factors and system’s effects and give examples where opt-out had detrimental effects on donation (Shepherd et al., 2014).

This underlines the importance of informal issues in transplantation, which remain major innovation barriers and high leverage points for system change in transplantation. In particular, mistrust resulting from human behaviour and system’s weaknesses stimulating illegal actions are important hurdles to successfully tackling the problems of donation and system quality. For instance, despite similar formal institutions like the opt-in policy or the legislation criteria of brain death and of cardiac death for organ donation, the effective donation rate in different countries6 vary because of differences in informal institutions like local culture, religious awareness or acceptance of the transplant medicine et vice versa. Ethical aspects (e.g., concepts of unscathed body and brain death), perceived inequality of organ allocation, or scandals involving forged paperwork (because of individual ambitions and reimbursement policies of the involved clinics and doctors) may hinder the interplay of interrelated innovations for system change.

As Kirste, former head of the German Organ Transplantation Foundation (DSO) stated in an interview in 2012, many possible donors in Germany are simply overlooked, because small hospitals are not perceived as elements of the transplant system and there is a lack of well-trained transplant commissaries and appropriate incentives for organ detection. The importance of such “overlooking” of potential donors is high for each hospital and much more likely to be the reason for low transplant rates than opt-in regulation (Boseley, 2013)

Being a very special subsystem of healthcare, transplantation requires addressing simultaneously several ethical, medical, technological, legal, socio-cultural and solidary issues. When it comes to implementation of related innovations for system change, formal and informal institutions can be main impulses to develop further RI required for systems change.

5. Summary and conclusions

This research explored a systemic approach to innovations in transplantation. In order to systematically identify crucial relationships between innovations, it started with a single (focal) innovation, the LAS and its related innovations. A qualitative design (Maxwell, 2012) facilitated the exploration of the different relations emerging around the topic of systemic innovations in transplantation.

A closer look at the particular effects of LAS on the system and the interrelatedness with other innovations enabled identifying the current transition of the LTx system. Core results of the study are summarised in Table 4:

Table 4.

Summary of core results.

| Systemic innovation | LAS was supported by and has generated itself other innovations and all together they transformed the LTx system towards a system with lower mortality rate and waiting time, with stable quality and more transplants. |

| Feedback loops | System change in transplantation is brought about or limited by feedback loops of introduced innovations, which activate additional innovations and transform the system directly, disruptively or via related innovations. |

| Transformational paths. | Reinforcing or balancing feedback loops lead to different transitional paths. |

| Leverage points | Systemic innovations are high leverage points for transforming transplant systems. Path dependency in the German set-up can be partly explained by informal rules like values, norms and culture. Thus, institutional innovations are core leverages to further transformations. |

| Systems thinking | Multiple interventions (leverages) coordinated in a holistic way are required for dealing with the diverse systems failures and managing systems change. |

The increase in transplants resulting from the shared implementation of systemic innovations addresses but does not solve the main failure of the system – its strong dependency on deceased donors. Choosing such system reconfigurations, rather than radical mechanisms of system change, implies that new failures of the system are expected to appear soon and will result in a new malfunction or even a new crisis of the system: increasing transplants based on ECD and RA indicating marginal quality of the organs might now affect positively transplant results (remaining good or even becoming better) but in the long term, adverse effects could evolve in the post-transplant phase. Thus, a feedback loop resulting from the recent systemic innovations could be more hindering and could lead to lower efficiency or at least a weakened system. There are for example newer studies dealing with the long-term effect of LAS in the USA, which indicated first negative impacts in the post-transplant phase: the increased use of resources during index hospitalisation (Maxwell et al., 2015), which could lead to a rebound effect of the financial advantages of less hospitalisation and shorter stationary pre-transplant stay. Also gender disparities and long-term post-transplant benefit of recipients are possible as the shift in diseases after LAS introduction is grounded in prioritising patients with the most urgent status (Salvadori & Bertoni, 2014).

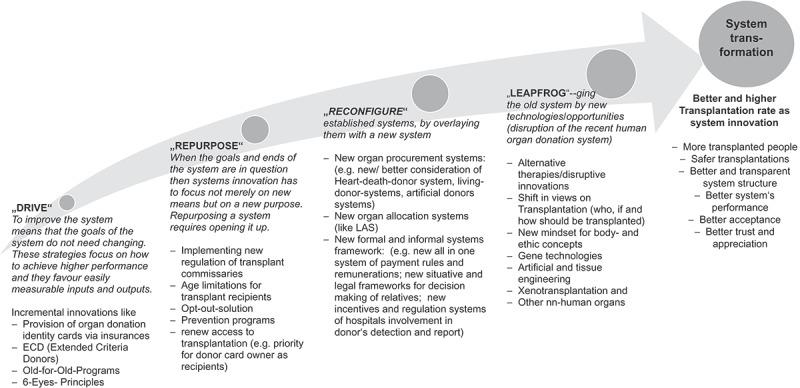

This study described the transition in LTx and hence drew other possible transformational pathways which could advance depending on future related innovations and on the political decision to support their interplay. For example, using Leadbeater’s approach on systemic innovations (already described in Table 2), four different transitions could be supported: drive, reconfigure, repurpose, leapfrog (Figure 4). Striving for alternative system goals or leapfrogging to new systems however could be promising and successful high levers for transformation: be it development of alternative transplant inputs (e.g. living organ transplantations or tissue engineering), limiting the need for transplants (by e.g. accelerating introduction of alternative treatments) or leapfrogging towards an artificial or xeno-transplant system where donation of human organs is no longer needed.

Figure 4.

Study results for possible paths of system change with respective leverage points in LTx systems.

Deciding to continue existing paths in transplantation (drive or reconfigure the system), it should be noticed that all systemic innovations will fail unless they bring about widespread changes in society regarding behaviour and social values. The case of LAS shows that the recent set of related innovations has already exhausted the current available potentials of the lung allocation and preservation system while opportunities in the system’s environment (of healthcare, society, mass media, policy and science) are still not seized.

There are limits in exploiting systemic innovations as balancing feedbacks to further drive the donation-oriented systems. Repurposing the system to one where transplantation has to implement a new purpose (of e.g. donation as a public good taking precedence over individual decision-making of donors) would be a holistic solution for improvement of existing reserves and functions of the system. It will clearly improve the rate but may hardly achieve a positive shift of informal institutions like acceptance and trust that are needed for a stable transformation. Reconfiguring the system with a new one, as happened in the case of LAS, has a high potential to cause successful change, provided that the main malfunctions of the “old” systems are replaced with suitable innovations which, however, seems to be a tough endeavour in the field of formal (policy) and informal (social) innovations. Courageous decision-makers could use the systemic innovation approach to introduce such required innovations at the different malfunctioning levels like new allocation-oriented systems, new prevention programmes or new (formal and informal) paths for non-human organ procurement. A leapfrogging would be the possible transition when related innovations in engineered organs speed up and replace the current donation-based system. Here, key potential is seen in the leapfrogging of the system towards non-human organs or in the reconfiguration of the system via radical formal and informal shifts.

This study pleads therefore for holistic policies and strategies of transformation in healthcare systems. That implies that new system goals, mindsets, and new medical-technological solutions and feedbacks are appropriate mechanisms for political attempts to innovate transplant systems. However, no strategy is based on complete information and could consider all possible relations. The holistic approach as proposed in this study is required and yet, also entails limitations of the study, namely limited replicability and validation of results. Since systems are unique, dynamic and self-replicative, their analysis is non-transferable to other systems. Thus case-by-case analysis of new systems and further studies on systemic innovations could supplement the study results and advance their understanding and are thus recommended for future research.

Funding Statement

We declare, that this research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Notes

Solid lung transplantation comprises mainly single-lung and double-lung transplant. There are also heart-lung transplants and living related lung transplantations, called lobar-lung transplantation. A closer consideration of those surgical innovations, however, would go beyond the scope of our article, and are thus not part of the analysis.

like COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease), lung fibrosis and cystic fibrosis etc.

Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovenia and, most recently Hungary.

e.g. when it is not possible to reach the donor centre in time, for example owing to bad weather conditions or when the donor is unstable.

in Germany this is the OCS™ device, see also the INSPIRE study (Warnecke et al., 2013).

In 2016, the USA reached a new transplantation record with the highest deceased donation rate of more than 30%, using the same legislative opt-in norms but having another informal institution and more (organisational, communicational and technological) innovative processes in the system than Germany with an organ donation rate of ca. 10% among its population. On the other hand there is a big gap to Austria (ca. 25%), a country with a very similar cultural background and norms to those of Germany, but using the opt-out norm and effective system structures (GODT 2016).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our reviewers for their very helpful comments. We believe that following these comments helped to improve the paper a lot. We sincerely want to express our gratitude to the experts, who were willing to give us detailed information and supported our study with their knowledge. Our special thanks goes hereby to (in the order of their interview date): Prof. Dr. Strueber, Prof. Dr. Reichenspurner, Dr. Samson-Himmelstjerna, Dr. Sommer, Mr. Schulz, Prof. Dr. Haverich, Dr. Richter, Dr. Oldigs, Mrs. Oelschner, Prof. Dr. Deuse, Dr. Heuer. We also sincerely thank Leonie Eising and Professor Markus Reihlen for their helpful remarks on this manuscript. We here with confirm that this manuscript has not been previously published, is not currently under consideration by any other journal, and will not be submitted to any other journal while submitted here for review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Declaration statements

• Availability of Data and Material

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Boseley, S. (2013, January 09). Mass donor organ fraud shakes Germany. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jan/09/mass-donor-organ-fraud-germany

- Braun, I. (1991). Geflügelte Saurier: Systeme zweiter Ordnung: Ein Verflechtungsphänomen großer technischer Systeme. FS II 91-501. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung [Google Scholar]

- Braun, I., & Joerges, B. (1993, January 01). How to recombine large technical systems: The case of European Organ transplantation. FS II 93-505. [Working Paper 93-27]. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, B. C., Raman, S. M., Selzman, C. H., & Liou, T. G. (2013). Use of older donors for lung transplantation-you can‘t get there from here. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation : the Official Publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation, 32, 757–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. W., & Teece, D. J. (1996). Organizing for innovation: When is virtual virtuous? Harvard Business Review, 74, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator‘s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colvin-Adams, M., Valapour, M., Hertz, M., Heubner, B., Paulson, K., Dhungel, V., … Israni, A. K. (2012). Lung and heart allocation in the United States. American Journal of Transplantation, 12, 3213–3234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daft, R. L. (2008). The leadership experience. Stamford, Conn.: Thomson/Sout-Western. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A., Mulgan, G., Norman, W., Pulford, L., Patrick, R., & Simon, J. (2012). Systemic innovation. Brussels, Belgium: Social Innovation Europe initiative (SIE). [Google Scholar]

- Dolata, U. (2011). Soziotechnischer Wandel als graduelle Transformation. Berliner Journal Soziol, 21, 265–294. [Google Scholar]

- Elzen, B., Geels, F. W., & Green, K. (editors). (2004). System innovation and the transition to sustainability: Theory, evidence and policy. Cheltenham, U.K, Northampton, Mass: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Eurotransplant International Foundation . (2014a). Eurotransplant Manual: Version 2.7 August 18, from Eurotransplant International Foundation. https://www.eurotransplant.org/cms/mediaobject.php?file=Chapter3_allocation15.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Eurotransplant International Foundation . (2014b). Eurotransplant Manual: Version 2.6 April 22. Chapter 3: Allocation, from Eurotransplant International Foundation: Online https://www.eurotransplant.org/cms/mediaobject.php?file=Chapter3_allocation13.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein, G. (1995). Das Transplantationssystem: Dynamik, Konflikte und ethisch-moralische Grenzgänge. Weinheim und München: Juventa-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F. W. (2004). Understanding system innovations: A critical literature review and conceptual synthesis. In Elzen B., Geels F. W., & Green K. (Eds.), System innovation and the transition to sustainability: Theory, evidence and policy (pp. 19–47). Cheltenham, U.K, Northampton, Mass: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F. W., & Schot, J. (2007). Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Research Policy, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, S. M., K-H, S., & Koch, U. (2001). Der Organspendeprozess. Ursachen des Organmangels und mögliche Lösungsansätze: Inhaltliche und methodenkritische Analyse vorliegender Studien; eine Expertise. Forschung und Praxis der Gesundheitsförderung: Vol. 13. Köln: BZgA. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, J., Greer, M., Sommerwerck, U., Deuse, T., Witt, C., Schramm, R., … Smits, J. M. (2014). Introduction of the lung allocation score in Germany. American Journal of Transplantation : Official Journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, 14, 1318–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, J., Smits, J., Schramm, R., Langer, F., Buhl, R., Witt, C., … Reichenspurner, H. (2017). Lung transplantation in Germany Since the introduction of the lung allocation score. A retrospective analysis. Deutsches Arzteblatt International, 114(11), 179–185. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, G. (2008). The future of management. Human Resource Management International Digest, 16. doi: 10.1108/hrmid.2008.04416fae.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hauerwaas, A., & Weisenfeld, U. (2017). Related innovations management in organisations. A systemic approach illustrated with the example of cancer-treating innovations in healthcare. Ijbg, 19, 350. [Google Scholar]

- IdW (Informationsdienst Wissenschaft e.V.) . (2017). Neue Diagnostik-Tools sollen langfristigen Transplantationserfolg steigern. https://idw-online.de/de/news668120

- Irving, M. J., Tong, A., Jan, S., Cass, A., Rose, J., Chadban, S., … Howard, K. (2012). Factors that influence the decision to be an organ donor: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation : Official Publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association, 27, 2526–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers, F. P. H. (2009). Organizing systemic innovation: Het organiseren van systemische innovatie (ERIM PhD Series in Research in Management). Rotterdam: Erasmus University. [Google Scholar]

- Joerges, V. (1996). Körper-Technik: Aufsätze zur Organtransplantation. Berlin: Sigma. [Google Scholar]

- Kaivo -Oja, J. (2011). Future of innovation systems and systemic innovation systems: Towards better innovation quality with new innovation management tools (FFRC eBOOK, 8). Turku, Finland: Writer & Finland Futures Research Centre, University of Turku. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H., Black Nembhard, H., Curry, W., Ghahramani, N., & Hwang, W. (2017). A systems thinking approach to prospective planning of interventions for chronic kidney disease care. Health Systems, 6(2), 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, S., Bölting, K., Kaluza, G., Schulz, K.-H., Ewers, H., Robbins, M. L., & Basler, H.-D. (2004). Bedingungen für die Bereitschaft zur Organspende. Zeitschrift für Gesundheitspsychologie, 12, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Krubiner, C. B., & Hyder, A. A. (2014). A bioethical framework for health systems activity: A conceptual exploration applying systems thinking;. Health Systems, 3, 124–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. (2014). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung (2nd ed.). Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U., Dresing, T., Rädiker, S., & Stefer, C. (2008). Qualitative evaluation: Der Einstieg in die Praxis (2nd ed.). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften/GWV Fachverlage GmbH Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar]

- Lamnek, S. (2005). Qualitative Sozialforschung. Lehrbuch. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater, C. (2013). The system innovator: Why successful innovation goes beyond products. In Mulgan G. & Leadbeater C. (Eds.), Systems innovation: Discussion paper (pp. 25–54). London: Nesta. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D. A. (2007). Transition management: New mode of governance for sustainable development = Transitiemanagement; nieuwe vorm van governance voor duurzame ontwikkeling. Utrecht: Internat. Books. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, N. (1996). Incongruence and tensions in complex organizations: Incongruence and tensions in complex organizations. Human Systems Management, 15, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, N. (1998). Using the Bodies of the Dead: Legal, ethical and organizational dimensions of organ transplantation. Brookfield, VT: Dartmouth/Ashgate Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mäkimattila, M. (2014). Organizing for systemic innovations: Research on knowledge, interaction and organizational interdependencies. Yliopistopaino: Lappeenranta Technical University (LUT). [Google Scholar]

- Mariscal, A., Cypel, M., & Keshavjee, S. (2017). Ex Vivo lung perfusion. Current Transplantation Reports, 4, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Maula, M., Keil, T., & Salmenkaita, J. P. (2006). Open innovation in systemic innovation contexts. In Chesbrough H. W., Vanhaverbeke W., & West J. (Eds.), Open innovation: Researching a new paradigm (pp. 241–257). New York, NY: Oxford University Press on Demand. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, B. G., Mooney, J. J., Lee, P. H. U., Levitt, J. E., Chhatwani, L., Nicolls, M. R., … Dhillon, G. S. (2015). Increased resource use in lung transplant admissions in the lung allocation score era. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 191, 302–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J. A. (2012). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system. Hartland VT: The Sustainability Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer. White River Junction, Vt: Chelsea Green Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. (2012). What might systemic innovation be? An exploratory essay. https://systemicinnovation.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/whatmightsibe-v101.pdf

- Mortati, M. (2013). Systemic Aspects of Innovation and Design: The perspective of collaborative networks. Cham, s.l.: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. (2013). Joined-up innovation: What is systemic innovation and how can it be done effectively?. In Mulgan G. & Leadbeater C. (Eds.), Systems innovation: Discussion paper (pp. 5–24). London: Nesta. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G., & Leadbeater, C. (editors). (2013). Systems innovation: Discussion paper. London: Nesta. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, D. H. (2014). The application of systems thinking in health: Why use systems thinking? Health Research Policy and Systems / BioMed Central, 12, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotmans, J., Kemp, R., & van Asselt, M. (2001). More evolution than revolution: Transition management in public policy. Foresight, 3, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, W. B. (2008). Health care as a complex adaptive system: Implications for design and management. The Bridge, 38(1), Spring, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Salvadori, M., & Bertoni, E. (2014). What‘s new in clinical solid organ transplantation by 2013. World Journal of Transplantation, 4, 243–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. (2014). Varianten qualitativer Inhaltsanalyse: Ein Wegweiser im Dickicht der Begrifflichtkeiten. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung, 15, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, K.-H., Gold, S., Knesebeck, M. V. D., & Koch, U. (2002). Der Organspendeprozess und Ansatzmöglichkeiten zur Erhöhung der Spenderate. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz, 45, 774–781. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, L., O‘Carroll, R. E., & Ferguson, E. (2014). An international comparison of deceased and living organ donation/transplant rates in opt-in and opt-out systems: A panel study. BMC Medicine, 12, 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits, J. M., van der Bij, W., & Rahmel, A. O. (2009). Allocation of donor lungs. In Fisher A. J., Verleden G. M., & Massard G. (Eds.), European Respiratory Monograph: Monograph 45 – Lung Transplantation (pp. 88–103). Plymouth, UK: European Respiratory Society Journals Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Smits, J. M., van der Bij, W., van Raemdonck, D., Vries, E. D., Rahmel, A., Laufer, G., … Meiser, B. (2011). Defining an extended criteria donor lung: An empirical approach based on the Eurotransplant experience. Transplant International : Official Journal of the European Society for Organ Transplantation, 24, 393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]