Abstract

Basis on molecular docking and pharmacophore analysis of naphthoquinone moiety, a total of 23 compounds were designed and synthesised. With the help of reverse targets searching, anti-cancer activity was preliminarily evaluated, most of them are effective against some tumour cells, especially compound 12: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-oxo-4-((4-phenoxyphenyl)amino) butanoate whose IC50 against SGC-7901 was 4.1 ± 2.6 μM. Meanwhile the anticancer mechanism of compound 12 had been investigated by AnnexinV/PI staining, immunofluorescence, Western blot assay and molecular docking. The results indicated that this compound might induce cell apoptosis and cell autophagy through regulating the PI3K signal pathway.

Keywords: Naphthoquinone moiety, anticancer activity, autophagy

1. Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is a severe malignant tumour associated with high mortality, especially in Asia1,2. Due to the non-specific symptoms in early appearance and the poor prognosis, the 5-year relative survival rate for GC was at most 20%3. Because of GC difficult diagnosis and chemotherapy resistance, it is necessary to investigate the new therapeutic drugs and deeply explore its anti-tumour mechanism4.

Autophagy is a pathway participated in the degradation of lysosomal, which contributed to renew the needed energy of cell survival during starvation5,6 and plays an important role in GC. Autophagy is expected to be a new target for molecular therapy7 which can inhibit the generation of tumour, on the other hand, can promote the survival and transfer of tumour cells8. A large number of studies have shown that autophagy is closely related to DC. For example, the gene polymorphism of autophagyis related to the susceptibility of GC9,10. Since lots of compounds regulating autophagy are discovered, but, the tumour microenvironments are complexity, the role of it in the tumour cells is not very clear. Therefore, it is necessary to reveal the title compounds’ anticancer mechanism through rational regulating of autophagy.

Compounds with naphthoquinone moiety show good activity against breast cancer, liver cancer, human cervical carcinoma and GC11–14 through inducing cell apoptosis15–21. Inducing autophagy is also one of the main mechanisms for anti-cancer activity13,22,23. Among them, PI3K and mTOR signalling pathways have been proved to be the main signal pathways to regulate autophagy24–27. However, for these kinds of derivatives, the poor selectivity and high cytotoxicity limit their clinical application. Therefore, how to reduce the toxicity and increase the selectivity is the main trend. Because the hydroxyl group of naphthoquinone is easily oxidised, and the polyhydroxy is not conducive to selectivity, so modification of the hydroxyl group is one of the main methods to study structure–activity relationship. Many reports showed that the introduction of suitable substituents on the hydroxyl group could improve activity28–30 and reduce toxicity31. Furthermore, Ahn32 and Sankawa33 showed that the side chain hydroxyl was not essential for activity. Both acylation and etherification could maintain antitumor activity at low concentration and the introduction of double bond should increase the activity obviously.

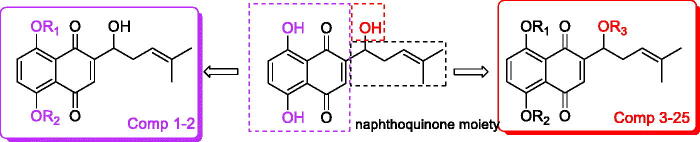

So, based on the above, combined with the results of reverse target finding, a series of new naphthoquinone-esterification/etherification derivatives targeting PI3K were designed and synthesised (Figure 1). Their inhibitory activities against SGC-7901, MGC-803, SMMC-7721, and U-87 cells were determined by MTT assay. The molecular mechanism of title compound was studied by influencing the signal pathway of PI3K/AKT/mTOR. Meanwhile molecular docking was used to determine the interaction between the compound and PI3K protein.

Figure 1.

The general design strategy in this study.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Chemistry

Adriamycin was purchased from Aladdin Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China) and other reagents were purchased from Abcam, Cell Signalling Technology (Boston, MA) and Beyotime (Shanghai, China). 1H NMR spectra were recorded on 400 MHz or 600 MHz and 13 C NMR spectra were obtained at 100 MHz or 150 MHz (Supplementary material).

2.1.1. General procedure for preparation of compounds 1 and 2

To a solution of shikonin in DMF was added iodomethane (CH3I, 2.0 equiv) orbenzyl bromide and K2CO3 (2.0 equiv) and the mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 6 h. The mixture was filtered and the residue was washed with EA, the filtrate was extracted by EA and combined organic layers were washed with water and brine. Evaporate the solvent and the products were purified by column chromatography to give product as a solid.

1: 2-(1-hydroxy-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl)-5,8-dimethoxynaphthalene-1,4-dione, Brown solid. Yield: 92.3%. m.p. 94.3 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 7.30 (s, 2H), 6.79 (s, 1H), 5.18–5.13 (m, 1H), 4.77–4.72 (m, 1H), 3.95 (s, 6H), 2.62–2.54 (m, 1H), 2.50 (s, 1H), 2.39–2.33 (m, J = 14.7, 7.5, 1H), 1.71 (s, 3H), 1.61 (s, 32H).

2: 5,8-bis(benzyloxy)-2-(1-hydroxy-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl)naphthalene-1,4-dione, Deep red solid. Yield: 37.6%. m.p. 60.0 °C.1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.42 (s, 1H), 7.31–7.17 (m, 7H), 6.86 (s, 1H), 6.02 (dd, J = 6.7, 4.9, 1H), 5.06 (t, J = 7.2, 1H), 2.97 (t, J = 7.7, 2H), 2.79–2.67 (m, 2H), 2.62–2.54 (m, 1H), 2.48–2.42 (m, 1H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.18, 176.68, 171.69, 167.39, 166.87, 148.11, 140.04, 136.08, 132.85, 132.68, 131.46, 128.56, 128.21, 126.43, 117.62, 111.78, 111.53, 69.48, 35.75, 32.83, 30.80, 25.76, 17.95. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 469.2064

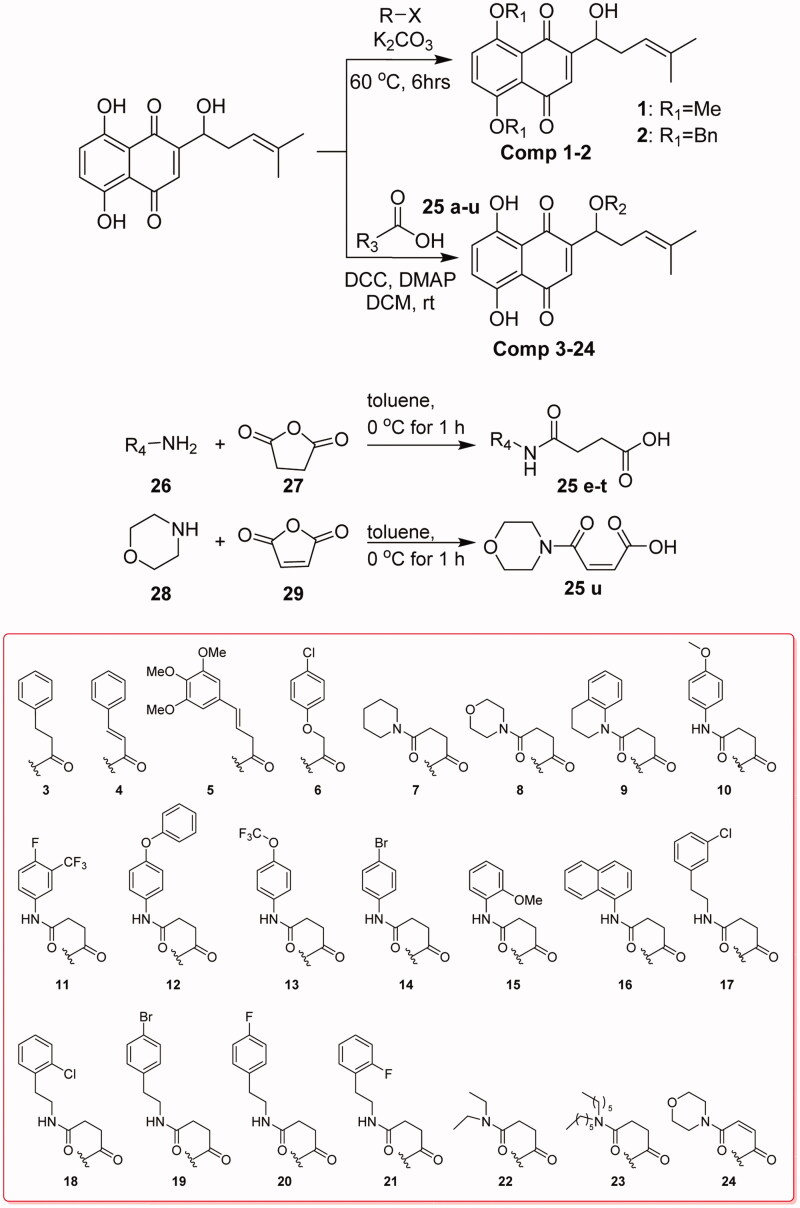

2.1.2. General procedure for preparation of compounds 3–24

To a solution of amine (1 equiv) in toluene (dichloromethane or furanidine according the amine’s solubility) was added succinic anhydride (1.1 equiv) or maleic anhydride (1.1 equiv). Then the solution was refluxed for 0.5 h. After TLC shows the reaction was completed, the solvent was cooled to room temperature. After filtration, cooled toluene was used washing the precipitate to give the crude product, if the product was dissolved in the solvent, the solvent was then removed under reduced pressure to crude product for next step directly.

At 0 °C, dicyclohexyl carbodiimide and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) were added and stirred in the solution of above-mentioned carboxylic acid and dichloromethane (DCM) for about 15 min. Then solution of shikonin in DCM was dropped, the combined solution was stirred in ice bath for 6 h, slowly to room temperature. After TLC showed the reaction was completed, the solution was concentrated and cooled to −10 °C and filtered to removal most of the dicyclohexylurea (DCU), the filtrate was evaporated, the product was purified via prepared TLC to give deep red solid.

3: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-3-phenylpropanoate, deep red solid. Yield: 37.6%. m.p. 60.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.42 (s, 1H), 7.31–7.17 (m, 7H), 6.86 (s, 1H), 6.02 (dd, J = 6.7, 4.9, 1H), 5.06 (t, J = 7.2, 1H), 2.97 (t, J = 7.7, 2H), 2.79–2.67 (m, 2H), 2.62–2.54 (m, 1H), 2.48–2.42 (m, 1H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.18, 176.68, 171.69, 167.39, 166.87, 148.11, 140.04, 136.08, 132.85, 132.68, 131.46, 128.56, 128.21, 126.43, 117.62, 111.78, 111.53, 69.48, 35.75, 32.83, 30.80, 25.76, 17.95. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 421.1632.

4: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl cinnamate, red solid. Yield: 64.6%. m.p. 85.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.61 (s, 1H), 12.50 (s, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 16.3, 1H), 7.73–7.70 (m, 1H), 7.54–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.39 (m, 2H), 7.21–7.16 (m, 3H), 6.45 (d, J = 16.2, 1H), 5.23–5.19 (m, 1H), 4.94–4.91 (m, 1H), 2.68–2.62 (m, 1H), 2.39–2.33 (m, 1H), 1.76 (s, 3H), 1.66 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 180.74, 179.95, 167.72, 165.38, 164.77, 153.99, 151.40, 137.52, 132.42, 132.27, 131.83, 130.91, 128.81, 128.26, 118.39, 112.02, 111.54, 103.67, 65.57, 35.67, 25.97, 18.09. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 419.1482.

5: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl (E)-4-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)but-3-enoate, red solid. Yield: 42.5%. m.p. 54.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.60 (s, 1H), 12.41 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 15.9, 1H), 7.17 (s, 2H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 6.76 (s, 2H), 6.39 (d, J = 15.9, 1H), 6.14–6.11 (m, 1H), 5.16 (t, J = 6.8, 1H), 3.89 (s, 6H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.57 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.16, 176.67, 167.51, 166.98, 165.60, 153.42, 148.24, 145.89, 140.33, 136.08, 132.88, 132.74, 131.50, 129.56, 117.69, 116.45, 111.82, 111.56, 105.33, 69.60, 60.96, 56.16, 32.90, 25.77, 18.00, 11.20. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 523.1964.

6: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-2-(4-chlorophenoxy)acetate, deep red solid. Yield: 85.2%. m.p. 102.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.39 (s, 1H), 7.26–7.22 (m, J = 10.1, 2H), 7.19–7.16 (m, 2H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 6.84 (d, J = 8.9, 2H), 6.15 (dd, J = 7.2, 4.7, 1H), 5.03 (t, J = 7.2, 1H), 4.68 (s, 2H), 2.66–2.60 (m, 1H), 2.51–2.47 (m, 1H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 176.20, 174.62, 169.24, 168.73, 167.64, 156.20, 146.63, 136.59, 133.56, 133.35, 131.17, 129.54, 126.93, 117.14, 115.86, 111.75, 111.53, 70.53, 65.40, 32.76, 25.76, 17.95. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 457.1032.

7: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-oxo-4-(piperidin-1-yl)butanoate, red solid. Yield: 65.2%. m.p. 120.0 °C.1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.56 (s, 1H), 12.43 (s, 1H), 7.19–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.06 (s, 1H), 6.03–5.98 (m, 1H), 5.16-5.08 (m, 1H), 3.57–3.47 (m, 2H), 3.42–3.33 (m, 2H), 2.73 (t, J = 6.4, 2H), 2.66–2.57 (m, J = 18.5, 11.9, 3H), 2.52–2.44 (m, 1H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.64–1.60 (m, J = 4.3, 2H), 1.57–1.48 (m, 7H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 194.47, 178.95, 177.49, 172.20, 168.93, 166.70, 166.18, 148.19, 135.96, 132.58, 132.35, 131.97, 117.71, 111.57, 69.62, 65.57, 46.29, 42.87, 32.77, 29.41, 27.92, 26.32, 25.77, 24.48, 17.96. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 456.2042.

8: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl 4-morpholino-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 26.4%. m.p. 105.0 °C.1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.56 (s, 1H), 12.43 (s, 1H), 7.19–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.05 (s, 1H), 6.01 (dd, J = 6.3, 5.3, 1H), 5.12 (t, J = 7.2, 1H), 3.68–3.63 (m, 4H), 3.61–3.58 (m, 2H), 3.48–3.45 (m, 2H), 2.75 (t, J = 6.6, 2H), 2.67–2.58 (m, 3H), 2.53–2.43 (m, 1H), 1.68 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.62, 177.13, 172.00, 169.50, 167.02, 166.50, 148.01, 136.03, 132.71, 132.49, 131.85, 117.65, 111.80, 111.56, 69.77, 66.83, 66.46, 45.61, 42.06, 32.76, 29.17, 27.71, 25.78, 17.96. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 458.1831.

9: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-(3,4-dihydroquinolin-1(2H)-yl)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 44.1%. m.p. 92.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.44 (s, 1H), 7.19–7.07 (m, 6H), 7.05 (s, 1H), 6.02–5.98 (m, 1H), 5.11 (t, J = 7.0, 1H), 3.83–3.73 (m, 2H), 2.82–2.78 (m, 2H), 2.77–2.75 (m, 2H), 2.72–2.69 (m, 2H), 2.64–2.58 (m, 1H), 2.52–2.45 (m, 1H), 1.98–1.88 (m, 2H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.55 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.72, 177.25, 171.93, 166.89, 166.38, 156.74, 148.11, 136.00, 132.65, 132.43, 131.88, 128.54, 126.10, 124.68, 117.66, 111.80, 111.56, 69.69, 49.12, 33.92, 32.77, 29.62, 26.77, 25.76, 25.59, 24.93, 23.96, 17.95. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 504.2024.

10: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-((4-methoxyphenyl)amino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 72.9%. m.p. 115.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.41 (s, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.8, 2H), 7.34 (s, 1H), 7.19–7.15 (m, 2H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.8, 2H), 6.04 (dd, J = 6.4, 5.3, 1H), 5.11 (t, J = 7.0, 1H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 2.83 (t, J = 6.6, 2H), 2.65 (t, J = 6.5, 2H), 2.62–2.58 (m, 1H), 2.52–2.46 (m, 1H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 207.18, 177.88, 176.40, 172.17, 169.21, 168.00, 167.47, 156.52, 147.82, 136.41, 133.16, 132.93, 131.79, 130.96, 121.70, 117.65, 114.23, 111.96, 111.72, 70.15, 55.60, 32.96, 31.98, 31.09, 29.73, 25.90, 18.11. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 494.1839.

11: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-((4-fluoro-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)amino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 63.2%. m.p. 137.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.56 (s, 1H), 12.39 (s, 1H), 7.76–7.72 (m, 1H), 7.70–7.63 (m, 2H), 7.19–7.13 (m, 2H), 7.11 (t, J = 9.3, 1H), 7.03 (s, 1H), 6.07–6.02 (m, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 6.9, 1H), 2.85–2.81 (m, 2H), 2.69–2.58 (m, 3H), 2.52–2.45 (m, 1H), 1.65 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 207.09, 177.19, 175.67, 172.03, 169.54, 168.32, 167.80, 147.36, 136.32, 136.29, 133.89, 133.20, 132.96, 131.44, 124.85, 118.30, 117.39, 117.22, 111.76, 111.51, 70.21, 32.78, 31.78, 30.92, 29.30, 25.71, 17.93. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 550.1437.

12: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-oxo-4-((4-phenoxyphenyl)amino)butanoate, red solid. Yield: 82.1%. m.p. 133.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.59–12.55 (m, 1H), 12.40 (s, 1H), 7.47–7.38 (m, 3H), 7.30 (t, J = 7.8, 2H), 7.19–7.13 (m, 2H), 7.07 (t, J = 7.4, 1H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 6.95 (t, J = 9.5, 4H), 6.06–6.02 (m, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 7.2, 1H), 2.84 (t, J = 6.5, 2H), 2.66 (t, J = 6.5, 2H), 2.64–2.57 (m, 1H), 2.49–2.42 (m, 1H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.60, 176.09, 172.01, 169.20, 167.94, 167.42, 153.39, 147.59, 136.26, 133.21, 133.05, 132.82, 131.57, 129.68, 123.02, 121.42, 119.57, 118.36, 117.46, 111.78, 111.55, 70.04, 32.80, 31.83, 29.48, 25.73, 17.95. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 556.1958.

13: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-oxo-4-((4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl)amino)butanoate, red solid. Yield: 58.6%. m.p. 134.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.56 (s, 1H), 12.40 (s, 1H), 7.56 (br, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.7, 2H), 7.18–7.11 (m, 4H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 6.05–6.02 (m, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 7.0, 1H), 2.83 (t, J = 6.4, 2H), 2.67 (t, J = 6.3, 2H), 2.64–2.58 (m, 1H), 2.52–2.45 (m, 1H), 1.65 (s, 3H), 1.55 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.38, 175.87, 171.99, 169.27, 168.15, 167.62, 147.45, 136.75, 136.29, 133.14, 132.89, 131.88, 131.53, 121.13, 117.42, 116.79, 111.76, 111.54, 70.12, 32.78, 32.00, 30.92, 29.41, 25.73, 17.94. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 548.1546.

14: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-((4-bromophenyl)amino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 77.6%. m.p. 105.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.56 (s, 1H), 12.40 (s, 1H), 7.47 (br, 1H), 7.40–7.33 (m, 4H), 7.19–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.03 (s, 1H), 6.06–6.01 (m, 1H), 5.09 (t, J = 7.2, 1H), 2.82 (t, J = 6.4, 2H), 2.68–2.57 (m, 3H), 2.53–2.44 (m, 1H), 1.65 (s, 3H), 1.55 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.38, 175.87, 171.99, 169.27, 168.15, 167.62, 147.45, 136.75, 136.29, 133.14, 132.89, 131.88, 131.53, 121.13, 117.42, 116.79, 111.76, 111.54, 70.12, 32.78, 32.00, 30.92, 29.41, 25.73, 17.94. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 542.0732.

15: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-((2-methoxyphenyl)amino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 87.3%. m.p. 113.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.42 (s, 1H), 8.32 (d, J = 7.8, 1H), 7.85 (br, 1H), 7.18–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.05–7.04 (m, 1H), 7.02–6.98 (m, 1H), 6.95–6.91 (m, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 8.2, 1H), 6.05–6.02 (m, 1H), 5.13–5.08 (m, 1H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 2.83 (t, J = 6.6, 2H), 2.72 (t, J = 6.5, 2H), 2.64–2.57 (m, 1H), 2.51–2.45 (m, 1H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.55 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 207.02, 177.72, 176.24, 172.01, 169.05, 167.84, 167.31, 156.36, 147.66, 136.25, 133.00, 132.77, 131.63, 130.80, 121.54, 117.49, 114.07, 111.74, 111.56, 69.99, 55.44, 32.80, 31.82, 30.93, 29.57, 25.74, 17.95. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 494.1853.

16: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-(naphthalen-1-ylamino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 74.8%. m.p. 127.0 °C.1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.54 (s, 1H), 12.26 (s, 1H), 7.94 (d, J = 7.1, 1H), 7.89 (br, 1H), 7.82–7.76 (m, 2H), 7.64 (d, J = 8.2, 1H), 7.47–7.37 (m, 3H), 7.17–7.10 (m, 2H), 6.97 (s, 1H), 6.11–6.04 (m, 1H), 5.14–5.05 (m, 1H), 2.93 (t, J = 5.5, 2H), 2.87–2.79 (m, 1H), 2.63–2.57 (m, 2H), 2.51–2.43 (m, 1H), 1.63 (s, 3H), 1.54 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.20, 172.38, 169.95, 167.43, 156.69, 147.43, 136.30, 133.90, 133.00, 132.72, 132.06, 131.41, 130.89, 128.81, 128.65, 126.66, 126.15, 125.85, 125.70, 125.63, 120.45, 117.43, 111.73, 70.18, 33.92, 32.77, 25.58, 24.91, 17.93. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 514.1846.

17: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-((3-chlorophenethyl)amino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 46.3%. m.p. 91.8 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.41 (s, 1H), 7.23–7.14 (m, 5H), 7.05 (d, J = 7.2, 1H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.01 (dd, J = 6.3, 5.1, 1H), 5.61 (s, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 7.3, 1H), 3.49–3.42 (m, 2H), 2.77–2.72 (m, 4H), 2.62–2.54 (m, 1H), 2.48–2.38 (m, 3H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.84, 176.33, 171.85, 171.02, 167.74, 167.20, 147.82, 140.82, 136.17, 134.34, 132.97, 132.74, 131.54, 129.84, 128.85, 126.91, 126.71, 117.53, 111.78, 111.54, 69.86, 40.53, 35.29, 32.81, 30.81, 29.44, 25.76, 17.95. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 526.1632.

18: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-((2-chlorophenethyl)amino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 76.6%. m.p. 97.8 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.41 (s, 1H), 7.34–7.32 (m, 1H), 7.20–7.14 (m, 5H), 7.01 (s, 1H), 6.01 (dd, J = 6.5, 5.2, 1H), 5.62 (s, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 7.3, 1H), 3.51 (dd, J = 13.2, 6.8, 2H), 2.92 (t, J = 7.0, 2H), 2.79–2.70 (m, 2H), 2.64–2.58 (m, 1H), 2.50–2.41 (m, 3H), 1.68 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, cdcl3) δ 177.85, 176.34, 171.84, 170.98, 167.73, 167.20, 147.84, 136.45, 136.17, 134.07, 132.96, 132.73, 131.55, 131.00, 129.59, 128.04, 126.97, 117.54, 111.79, 111.55, 69.81, 39.28, 33.29, 32.82, 30.81, 29.44, 25.76, 17.95. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 526.1662.

19: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl-4-((4-bromophenethyl)amino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 69.4%. m.p. 134.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.58 (s, 1H), 12.41 (s, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 8.2, 2H), 7.16 (s, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.2, 2H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.06–5.95 (m, 1H), 5.58 (s, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 7.1, 1H), 3.49–3.43 (m, 2H), 2.77–2.70 (m, 4H), 2.61–2.56 (m, 1H), 2.52–2.47 (m, 1H), 2.42 (t, J = 6.7, 2H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.77, 176.25, 171.85, 170.99, 167.81, 167.28, 147.80, 137.72, 136.18, 132.99, 132.78, 131.65, 131.51, 130.46, 120.35, 117.52, 111.78, 111.54, 69.85, 40.55, 35.05, 33.92, 32.81, 30.79, 29.42, 25.76, 25.58, 17.95. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 570.1137.

20: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl 4-((4-fluorophenethyl)amino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 54.2%. m.p. 116.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.41 (s, 1H), 7.16 (s, 2H), 7.14–7.10 (m, 2H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.97 (t, J = 8.6, 2H), 6.05–6.00 (m, 1H), 5.59 (br, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 7.3, 1H), 3.51–3.44 (m, 2H), 2.77–2.70 (m, J = 6.8, 4H), 2.66–2.55 (m, 1H), 2.52–2.45 (m, 1H), 2.42 (t, J = 6.8, 2H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.80, 176.28, 171.86, 170.96, 167.78, 167.25, 162.42, 160.79, 147.81, 136.18, 132.98, 132.76, 131.52, 130.13, 130.08, 117.52, 115.45, 115.31, 111.78, 111.54, 69.84, 40.81, 34.82, 32.81, 30.80, 29.44, 25.75, 17.94. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 510.1936.

21: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl 4-((2-fluorophenethyl)amino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 75.5%. m.p. 91.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.41 (s, 1H), 7.21–7.15 (m, 4H), 7.06 (t, J = 7.4, 1H), 7.03–6.98 (m, 2H), 6.04–5.98 (m, 1H), 5.64 (br, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 7.2, 1H), 3.49 (q, J = 6.7, 2H), 2.83 (t, J = 6.9, 2H), 2.75–2.69 (m, 2H), 2.64–2.58 (m, 1H), 2.50–2.46 (m, 1H), 2.43 (t, J = 6.9, 2H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.92, 176.41, 171.83, 170.98, 167.67, 167.14, 162.03, 160.41, 147.86, 136.16, 132.94, 132.71, 131.56, 131.14, 131.11, 128.35, 128.30, 125.74, 125.63, 124.21, 124.19, 117.55, 115.40, 115.26, 111.79, 111.54, 69.80, 39.67, 32.81, 30.79, 29.45, 29.09, 25.75, 17.94. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 510.1966.

22: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl 4-(diethylamino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 78.5%. m.p. 77.0 °C.1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.43 (s, 1H), 7.19–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.05 (s, 1H), 6.02–5.99 (m, 1H), 5.12 (t, J = 7.2, 1H), 3.36 (q, J = 7.1, 1H), 3.31 (q, J = 7.1, 2H), 2.75 (t, J = 6.7, 2H), 2.65–2.58 (m, 3H), 2.52–2.47 (m, 1H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H), 1.18 (t, J = 7.1, 3H), 1.08 (t, J = 7.1, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.85, 177.39, 172.17, 169.81, 166.79, 166.27, 148.18, 135.95, 132.60, 132.37, 131.92, 117.70, 111.82, 111.57, 69.65, 41.73, 40.28, 32.78, 29.43, 27.85, 25.75, 17.94, 14.12, 13.04. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 444.2024.

23: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl 4-(dihexylamino)-4-oxobutanoate1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl 4-(dihexylamino)-4-oxobutanoate, red solid. Yield: 53.8%. m.p. 78.3 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.56 (s, 1H), 12.44 (s, 1H), 7.19–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.05 (s, 1H), 6.00 (dd, J = 6.3, 5.0, 1H), 5.12 (t, J = 7.2, 1H), 3.29–3.25 (m, 2H), 3.22–3.18 (m, 2H), 2.74 (t, J = 6.7, 2H), 2.65–2.58 (m, 3H), 2.51–2.45 (m, 1H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.55 (s, 3H), 1.32–1.21 (m, 16H), 0.90–0.83 (m, 6H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.92, 177.47, 172.18, 170.11, 166.71, 166.19, 148.19, 135.94, 132.58, 132.34, 131.96, 117.71, 111.81, 111.56, 69.62, 47.82, 46.17, 32.78, 31.60, 31.50, 29.69, 29.48, 28.87, 27.90, 27.71, 26.70, 26.60, 25.77, 22.59, 17.95, 14.04, 13.99. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 556.3284.

24: 1-(5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl (Z)-4-morpholino-4-oxobut-2-enoate, red solid. Yield: 49.6%. m.p. 104.0 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.40 (s, 1H), 7.17 (s, 2H), 7.02 (s, 1H), 6.61 (d, J = 11.9, 1H), 6.12 (d, J = 11.9, 1H), 6.09 (dd, J = 6.3, 4.9, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 7.1, 1H), 3.74–3.58 (m, 4H), 2.91 (dd, J = 16.5, 4.5, 2H), 2.76 (dd, J = 16.6, 4.6, 2H), 2.67–2.61 (m, 1H), 2.53–2.45 (m, 1H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.55 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 180.62, 179.13, 174.00, 171.50, 169.02, 168.50, 150.01, 138.03, 137.29, 134.71, 134.49, 133.85, 124.11, 119.65, 113.80, 113.56, 71.77, 68.83, 68.46, 47.61, 44.06, 29.71, 27.78, 19.96. HR-ESI-MS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for 456.1628.

2.2. Cell culture

MGC-803, SGC-7901, U87 and SMMC-7721 cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were incubated in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

2.3. Cell viability assay

MGC-803, SGC-7901, U87 and SMMC-7721 cells were plated in 96-well plate at 7000 per well. Cells were incubated with the different concentrations of the compounds for 48 h. Subsequently, MTT (0.5 mg/mL) were used to test the cell viability, then 150 μL DMSO was added to each well after cells were incubated for 4 h and the absorbance was measured at 492 nm.

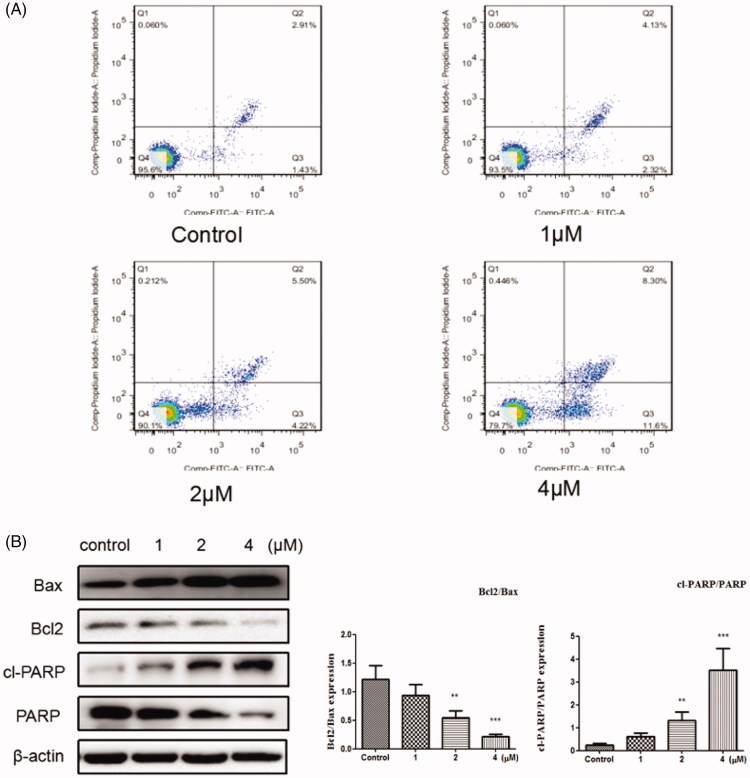

2.4. Apoptosis assay

After the indicated treatments for 48 h, cells were collected, washed three times with cold PBS, centrifuged and resuspended with 400 μL AnnexinV binding buffer per tube. Then the cells were stained with 5μLAnnexinV-FITC and incubated in the dark for 10 min on ice. Finally, 10 μL PI staining solution was added, and cells were detected by the flow cytometry after incubated in the dark for 5 min. Flowjo 7.6.1 software was used to analyse the cell apoptosis.

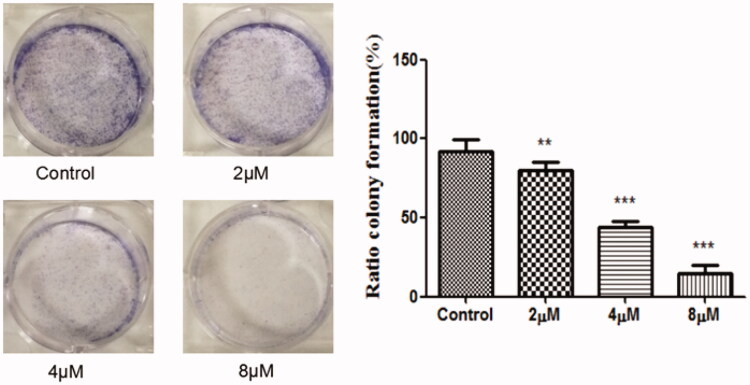

2.5. Colony formation assay

SGC-7901 cells (8000/well) were seeded in 6-well plate, and treated with indicated concentrations of compound 12 (2 μM, 4 μM, 8 μM) for 12 d. The medium was removed and methanol (500 μL/well) was added to fix at the cells for 3 min. Then cells were stained with giemsa working fluid for 15 min and washed with PBS. The number of colonies was counted.

2.6. Acridineorange (AO) staining

PH-sensitive Acridine orange (AO) was used to label acidic vesicles. Human gastric cancer cells were seeded in laser confocal dishes at 10,000/ml. After indicated treatment of compound 12 (1 μM, 2 μM, 4 μM) for 48 h, cells were stained with AO (1 μg/ml) for 15 min at the cell culture incubator. After the cells were washed by PBS, pictures were acquired under laser confocal microscope.

2.7. GFP-LC3 transfection

A plasmid GFP-tagged LC3 reporter gene (0.8 μg/500 μL) was transfected into SGC-7901 cells by Lipofectamine 2000, then cells were incubated for 24 h. After different treatments for 24 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and washed three times with PBS. Finally, Laser confocal dishes were analysed using confocal microscope.

2.8. Western blot analysis

RIPA lysis buffer was used to dissociate the treated cells. Cells were lysed and the supernatant was harvested after centrifuged for 30 min. The cell proteins were separated using Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and then they were transferred to the PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with skimmed milk solution (5%) for 2 h, then incubated with primary antibodies (1:1000, cst) for 20 h at 4 °C. The membranes were detected by chemiluminescence reagent after probed with the secondary antibody for 1 h.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data were represented as the mean ± SD (standard deviation). GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) were used to analyse significance by one-way ANOVA. p < 0.05 was expressed a significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. Scaffold design

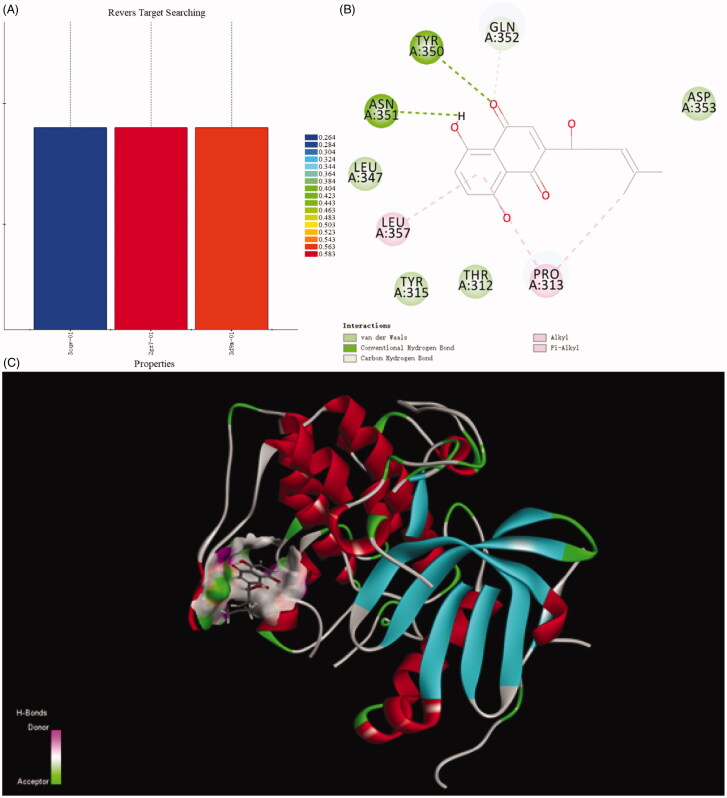

Discovery Studio 2018 was used as computation programme and naphthoquinone moiety as ligand to execute reverse targets searching programme, targets were searched to suit the pharmacophores of protein active sites in the database. Comparison with protein data bank, the results indicated the PI3K/Akt signal pathway was the target of naphthoquinone moiety. The lower most CDDOCKER energy of all conformations is 6.13917 kcal/m. The moiety interacted with protein active site through those forces, containing van der Waals force, conventional hydrogen bond, carbon hydrogen bond, alkyl and Pi-alkyl interactions. Van der Waals force formed between naphthoquinone and the receptors (Thr312, Tyr315, Leu347, Gln352). There was a hydrogen bond interaction between Asn351 and compound. Alkyl and Pi-Alkyl interacts with the aryl ring and the alkyl group via Leu357 and Pro313 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ligand profiler and docking result of naphthoquinone moiety.

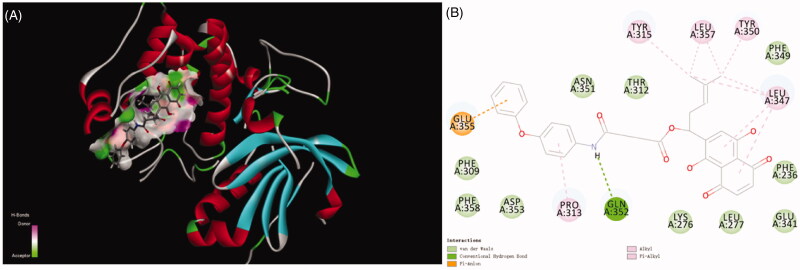

Title compound 12 has five kinds of interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, Pi-Anion force, Pi-alkyl interactions, and conventional van der Waals force which were formed with Phe309, Phe349, Phe358, Asp353, Asn351, Thr312, Lys276, Leu277, Glu341 and Phe236. Between the nitrogen of the compound and Gln352 formed the hydrogen bond. There also existed a Pi-anion interaction between aryl ring and the Glu355. Alky and Pi-Alkyl interactions were formed between aryl rings and Pro313, Tyr315, Leu357, Tyr350 and Leu347. Compared with naphthoquinone moiety, there was more stronger interaction of compound 12 than that of it. The differences of CDDOCKER energy also proved this. (The lower most CDDOCKER Energy of compound 12 is −15.7597 kcal/m and naphthoquinone is 6.13917 kcal/m). These data indicated that the combination of title compound 12 with the cavity site of Akt (PDB ID:3CQW) is spontaneous, which was more easier than that of naphthoquinone moiety (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Docking result of compound 12 with Akt.

3.2. Chemistry

Compounds 1 and 2 can be obtained by substitution of halides with phenol hydroxyls of naphthoquinone. The condensation reaction between hydroxyl group on side-chain of naphthoquinone and the related acids can get compounds 3–24. Compounds 25e–u were obtained from succinic anhydride or maleic anhydride after ring-opening reaction (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of title compounds 1–24.

3.3. Evaluation of anti-proliferation activity

Compounds 1–24 were detected for anticancer activities against SGC-7901, MGC-803, SMMC-7721, U-87 cell lines in vitro by the MTT assay, and ADM was used as the positive control34. From Table 1, when the phenolic hydroxyls of naphthoquinone moiety were converted to ether, the activity was missing. Compounds 9, 11, 12, 13, 17 and 20 have good activity which showed that hydroxyl group on side-chain of naphthoquinone moiety was modifiable and the introducing of hydrogen-bond donor, acceptor and hydrophobic group could benefit the activity. Compound 12 displayed high activity against the MGC-803, SGC-7901 and U87 cells with the IC50s of 4.07, 4.09 and 3.85 μM, respectively. So colony formation assay of this compound (Figure 4) was used to investigate the effect of it on cell proliferation in SGC-7901 cells. The experiment examined the ability for producing colonies after the cells were treated with the cell death agents35,36. The results exhibited that the colonies were decreased with the increased concentration of the title compound compared with the control group, which revealed this compound could inhibit the cell proliferation.

Table 1.

In vitro anticancer activities of compounds 1–24 against U 87, SMMC-7721, SGC-7901, MGC-803 cell lines.

| Compounds | IC50 μM (n = 3) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U87 | SMMC-7721 | SGC-7901 | MGC-803 | L02 | |

| 1 | – | – | – | – | –a |

| 2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3 | 8.0 ± 0.85 | 15.6 ± 3.3 | 10.6 ± 4.3 | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 13.6 ± 1.5 |

| 4 | 65.7 ± 2.7 | 75.1 ± 0.4 | – | – | |

| 5 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7 | 9.68 ± 2.3 | 14.4 ± 1.5 | 33.6 ± 2.1 | 9.7 ± 2.3 | 36.8 ± 4.1 |

| 8 | 10.0 ± 1.6 | 16.7 ± 1.8 | 20 ± 3.9 | 10.4 ± 0.7 | >50 |

| 9 | 4.45 ± 0.66 | 12.3 ± 0.1 | 8.6 ± 2.5 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 12.1 ± 0.8 |

| 10 | 12.3 ± 2.8 | 12.4 ± 2.6 | 11.1 ± 1.2 | 7.9 ± 1.8 | 11.9 ± 0.6 |

| 11 | 3.75 ± 0.77 | 9.5 ± 0.8 | 2.25 ± 1.5 | 8.4 ± 3.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 |

| 12 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 20.6 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 2.6 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | >50 |

| 13 | 3.46 ± 0.31 | 16.9 ± 2.2 | 7.8 ± 3.7 | 10.2 ± 2.9 | 15.8 ± 1.1 |

| 14 | – | 14.8 ± 0.1 | 10.7 ± 1.8 | 10.2 ± 1.3 | 16.2 ± 1.7 |

| 15 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 16 | 5.41 ± 0.67 | 24.3 ± 1.7 | 5.6 ± 2.6 | 5.9 ± 2.6 | 13.0 ± 2.4 |

| 17 | 3.8 ± 1.7 | 15.9 ± 0.2 | 20.8 ± 0.5 | 6.7 ± 2.4 | 11.4 ± 1.8 |

| 18 | 7.7 ± 4.4 | 17.9 ± 1.6 | 23.7 ± 0.5 | 6.6 ± 4.7 | 20.2 ± 2.0 |

| 19 | 9.1 ± 2.5 | 17.9 ± 1.0 | 7.6 ± 2.3 | 5.7 ± 2.4 | 8.5 ± 0.4 |

| 20 | 5.2 ± 1.4 | 18.6 ± 3.6 | 13.3 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 1.4 | 12.3 ± 0.5 |

| 21 | 6.1 ± 0.6 | 15.4 ± 0.4 | 14.8 ± 1.6 | 6.9 ± 3.9 | 16.0 ± 2.2 |

| 22 | 40.7 ± 4.7 | 46.5 ± 1.7 | 19.8 ± 1.8 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | >50 |

| 23 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 24 | 20.6 ± 0.6 | 50.1 ± 0.8 | 38.5 ± 0.7 | 40.8 ± 1.9 | – |

| ADM | 0.57 ± 0.32 | 0.46 ± 0.63 | 0.72 ± 0.12 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | – |

aInactive at 100 µM (highest concentration tested).

Figure 4.

The SGC-7901 cells formed colonies (counted with Image-ProPlus) after treated with various concentrations of the compound 12 for 12 d. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared with the control group.

3.4. Metabolic stability assay in human liver microsomes

To initially evaluate the stability of compound 12, we then tested the liver microsome stability of this compound. The Mean % Parent Remaining of compound 12 in metabolic stability test were 100, 95, 85, 80, and 70 at 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min, respectively. The calculated clearance rate was >110 μL/min/mg and the half-life (t1/2) was more than 60 min which indicated the acceptable stability.

3.5. Induces apoptosis

Apoptosis is one of the main methods that result in cell death37–39. In this study, Annexin V-FITC/PI kit was used to evaluate the cell apoptosis. From Figure 5(A), it can be see that after the cells were treated with the compound 12 (1, 2, and 4 μM) for 48 h, the total apoptosis was increased to 6.45%, 9.72%, and 19.9%, respectively, compared to the control group (4.34%). These results indicated that compound 12 induced apoptosis was associated with a dose dependent. To further, investigate whether the cell apoptosis induced by title compound, Western blot analysis was used to measure the effect of the compound on apoptosis of SGC-7901 cell. As reported that apoptosis pathway could be regulated by the activation of PARP and Bcl2 family proteins40,41. It can be found that the levels of Bax and cleaved PARP were up-regulated and the level of Bcl2 was down-regulated by the increased concentration of compound 12, which suggested that compound could promote apoptosis in SGC-7901l cells (Figure 5(B)).

Figure 5.

(A) Apoptosis ratio was detected by Annexin V/PI staining on the SGC-7901 cells treated with various concentration of title compound 12 (1, 2, 4 μM). (B) Western blots were used to detect the Bax, Bcl-2, cleaved PARP and full length PARP protein expression. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 compared with the control group.

3.6. Induces autophagy

Autophagy is a process of lysosomal degradation that can deliver the cytoplasmic cargo to the lysosome42. To assess whether compound 12 could promote autophagy on SGC-7901 cells, the expressions of autophagy-related proteins were examined. Autophagy will be switched on when LC3-I was converted into LC3-II, and the level of LC3-II involves in the formation of autophagosome. Meanwhile p62 is a marker of the degradative lysosome43,44. As shown in Figure 6(A), compound can decrease the level of P62 and increase the expressions of LC3II and Beclin1. The preliminary results suggest that title compound may promote autophagy.

Figure 6.

(A) Western blots assay examined the expressions of LC3-II/LC3-, P62, Beclin1. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared with the control group. (B) SGC-7901 cells were stained with AO after exposed to compound 12 for 48 h, then detected by the confocal microscopy at 200×. (C) SGC-7901 cells were transfected with GFP-LC3 plasmid, and treated with compound 12 alone (4 μM), 3MA (500 μM, pro-incubated for 1 h), compound 12 and 3MA, then observed under a confocal microscopy at 200×.

Another typical feature of autophagy is the accumulation of the acidic autophagic vacuoles (AVOs)45,46. To verify the development of AVOs, Acridine Orange (AO) staining was used to examine whether the acidic vesicular organelles in SGC-7901 cells were increased. AO produces red fluorescence when it accumulates in acidic regions such as autophagy lysosomes and lysosomes and produces bright green fluorescence in the cytoplasm and the nucleus47. As it can be seen in Figure 6(B), red fluorescently labelled vesicle acidic accumulated obviously as the increased concentrations of title compound (1, 2, and 4 μM). GFP-LC3 indicating technique was also used to detect the autophagy at the same time. When autophagy is formed, multiple bright green fluorescent spots will form as the GFP-LC3 fusion protein can translate to autophagosome membrane48. From Figure 6(C), compared to the blank control group, GFP-LC3 puncta were increased after cells treated with compound 12 (4 μM) meanwhile decreased after treated with compound 12 (4 μM) and 3-MA (500 μM). This further proved that title compound can promote autophagy.

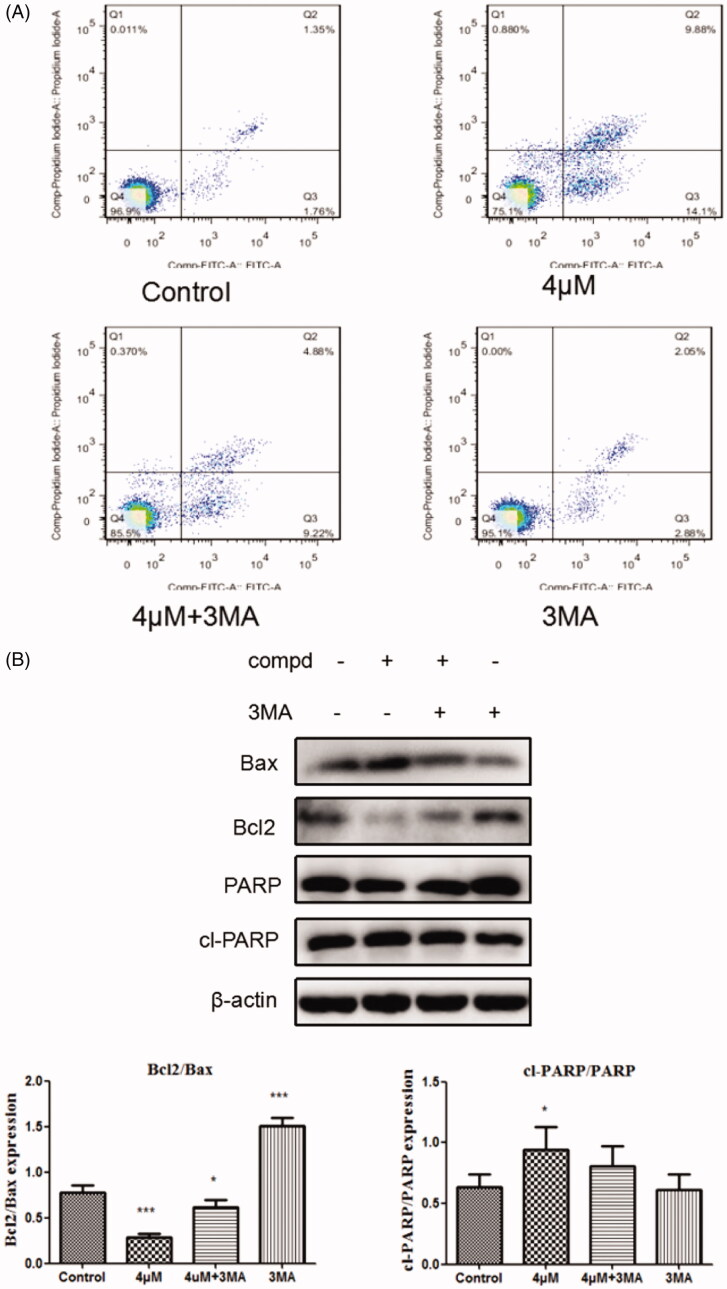

3.7. Role of autophagy regulation

The connection between apoptosis and autophagyis complicated because autophagy can promote apoptosis49,50, and can also suppress apoptosis51,52. To investigate whether autophagy has an impact on cell apoptosis induced by title compound, the cells were treated with compound 12 (4 μM) for 48 h co-treatment with or absence of the 3-MA (500 μM) in the apoptosis assays (Figure 7(A)) detected by the flow cytometry. Compared with compound 12, the apoptosis rate of treatment group cells in the presence of 3-MA decreased. At the same time, the levels of apoptosis-related proteins were examined in Western blot assay (Figure 7(B)), it was found that the up-regulation of apoptosis protein Bax and cl-PARP and the down-regulation of Bcl-2 was inhibited in the group with 3-MA. These results indicated that cell autophagy induced by compound 12 might promote the apoptosis of SGC-7901 cells.

Figure 7.

(A) Cells were treated with compound 12 alone (4 μM), 3MA (500 μM, pro-incubated for 1 h), compound 12 combined with 3MA and the Annexinv-FITC staining was used to evaluate the apoptosis ratio. (B) The activation of Bax, Bcl2, cl-PARP were determined by the western blot after SGC-7901 cells were exposed to compound 12 for 48 h with or without of 3MA (500 μM). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 compared with the control group.

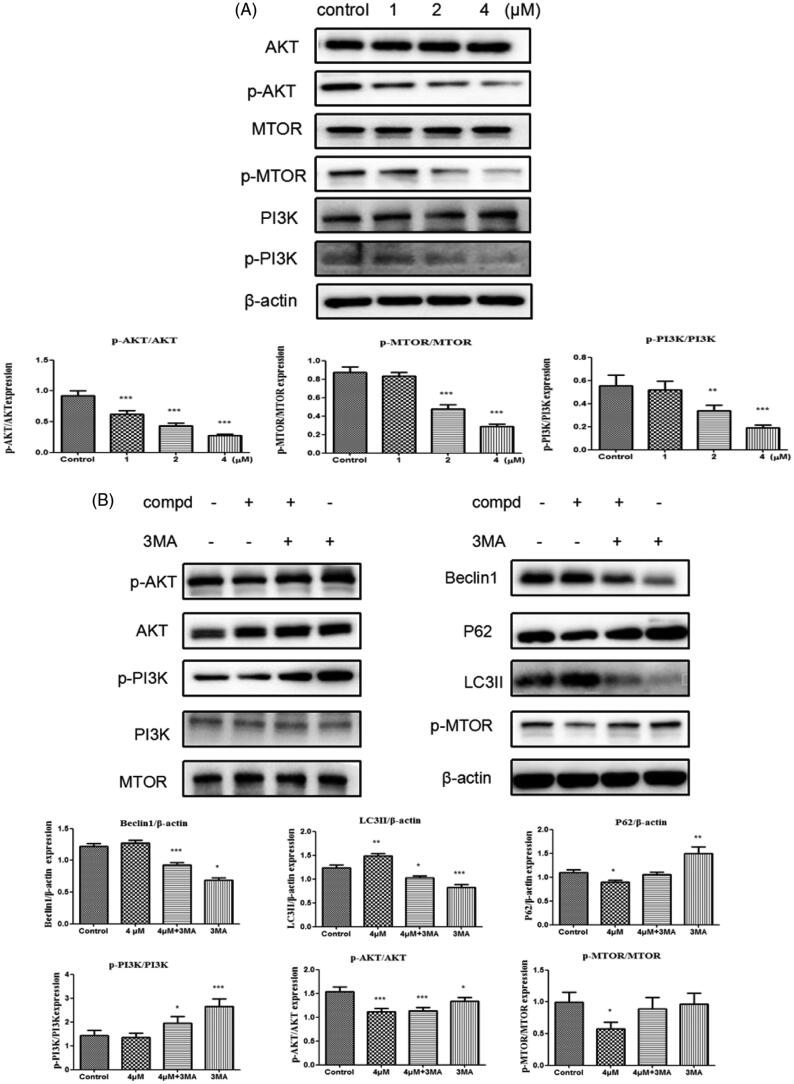

3.8. Suppression of activation of the PI3K/AKT/MTOR pathway

As a therapeutic target for cancer, the PI3K/AKT/MTOR signalling pathway participates in regulating autophagy53–56. Consequently, Western blot experiment was used to explore the impact of compound 12 on the level of phospho-PI3K, phospho-AKT and phospho-mTOR. After cells were treated with title compound for 48 h, the expression of p-PI3K, p-AKT and p-MTOR were decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 8(A)). 3-MA (3-methyladenine) is also a PI3K inhibitor57, so compound 12 (4 μM) with 3-MA (500 μM) were used to treated the cells. The experimental data showed that the ratio of p-PI3K/PI3K, p-AKT/AKT and p-MTOR/MTOR increased in the experiment of compound 12 with 3-MA compared with compound 12 alone (Figure 8(B)). These results revealed title compound could induce cell autophagy via inhibiting PI3K pathway.

Figure 8.

(A) Western blots were performed to observe the PI3K, p-PI3K, AKT, p-AKT, mTOR, p-MTOR protein expression incubated with compound 12 (1 μM, 2 μM, 4 μM) for 48 h. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared with the control group. (B) The expression levels of LC3-II, Beclin-1, P62 and PI3K signalling were analysed by western blotting assay with or without pre-treatment of 3MA (500 μM). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 compared with the control group.

4. Conclusion

According to result of ligand profiler and docking, a series of naphthoquinone derivatives were designed and synthesised. The preliminary activity results showed that several compounds had good anticancer activity. The anticancer mechanism of one compound against SGC-7901 cells was investigated further. The expression of LC3-II and Beclin1increased and the expression of P62 decreased after treated with this compound, which means that this compound helps promote the cell autophagy. Moreover, in Western blot and GFP-LC3 studies, the level of LC3-II/LC3-I decreased and autophagosome puncta was reduced after pre-treatment with 3-MA, which further verify our view. In addition, the cell apoptosis induced by this compound was inhibited and the cell viability was increased when the cell autophagy was blocked by 3-MA. Sequentially, the levels of p-MTOR, p-AKT, and p-PI3K were suppressed after incubated with compound, and these indicated that title compound could negatively regulate the PI3K pathways. In conclusion, title compound could inhibit cancer cell growth by promoting autophagy.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Nos. 21977001 and 21602029], the Horizontal cooperation project of Fuyang municipal government [Nos. XDHX201722 and XDHX2016026], Anhui Province Foundation [No. 18030701213], Horizontal cooperation project of Yifan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd [HX2019033], and Technological Fund of Fuyang normal university [2017FSKJ16].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Zhao TT, Xu H, Xu HM, et al. The efficacy and safety of targeted therapy with or without chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer treatment: a network meta-analysis of well-designed randomized controlled trials. Gastric Cancer 2018;21:361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine B, Kroemer G.. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 2008;132:27–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao Y, Luo Y, Zou J, et al. Autophagy and its role in gastric cancer. Clin Chim Acta 2019;489:10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satyavarapu EM, Das R, Mandal C, et al. Autophagy-independent induction of LC3B through oxidative stress reveals its non-canonical role in anoikis of ovarian cancer cells . Cell Death Dis 2018;9:934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Eisenberg-Lerner A, Bialik S, H-U S, et al. Life and death partners: apoptosis, autophagy and the cross-talk between them. Cell Death Differ 2009;16:966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meng Y, Yong Y, Yang G, et al. Autophagy alleviates neurodegeneration caused by mild impairment of oxidative metabolism. J Neurochem 2013;126:805–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Y Ávalos, Canales J, Bravo-Sagua R, et al. Tumor suppression and promotion by autophagy. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:603980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castaño-Rodríguez N, Kaakoush NO, Goh KL, et al. Autophagy in Helicobacter pylori infection and related gastric cancer. Helicobacter 2015;20:353–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burada F, Plantinga TS, Ioana M, et al. IRGM gene polymorphisms and risk of gastric cancer. J Dig Dis 2012;13:360–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du W, Hao X, Yuan Z, et al. Shikonin potentiates paclitaxel antitumor efficacy in esophageal cancer cells via the apoptotic pathway. Oncol Lett 2019;18:3195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu B, Jin J, Zhang Z, et al. Shikonin exerts antitumor activity by causing mitochondrial dysfunction in hepatocellular carcinoma through PKM2–AMPK–PGC1α signaling pathway. Biochem Cell Biol 2019;97:397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li B, Yuan Z, Jiang J, et al. Anti-tumor activity of Shikonin against afatinib resistant non-small cell lung cancer via negative regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Biosci Rep 2018;38:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu JP, Liu D, Gu JF, et al. Shikonin inhibits the cell viability, adhesion, invasion and migration of the human gastric cancer cell line MGC-803 via the Toll-like receptor 2/nuclear factor-kappa B pathway. J Pharm Pharmacol 2015;67:1143–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papageorgiou VP, Assimopoulou AN, Couladouros EA, et al. The chemistry and biology of alkannin, shikonin, and related naphthazarin natural products. Angew Chem Int Ed 1999;38:270–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng B, Feng Y, Deng B.. TIPE2 mediates the suppressive effects of shikonin on MMP13 in osteosarcoma cells. Cell Physiol Biochem Int J Exp Cell Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 2015;37:2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andújar I, Ríos JL, Giner RM, et al. Shikonin promotes intestinal wound healing in vitro via induction of TGF-β release in IEC-18 cells. Eur J Pharm Sci 2013;49:637–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Kang X, Niu G, et al. Shikonin induces apoptosis and prosurvival autophagy in human melanoma A375 cells via ROS-mediated ER stress and p38 pathways, Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2019;47:626–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong K, Zhang Z, Chen Y, et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase, receptor interacting protein, and reactive oxygen species regulate shikonin-induced autophagy in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Pharmacol 2014;738:142–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu T, L Xu, C Wang, et al. Alleviation of hepatic fibrosis and autophagy via inhibition of transforming growth factor-β1/Smads pathway through shikonin. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;34:263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HJ, Hwang KE, Park DS, et al. Shikonin-induced necroptosis is enhanced by the inhibition of autophagy in non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Transl Med 2017;15:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi S, Cao H.. Shikonin promotes autophagy in BXPC-3 human pancreatic cancer cells through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Oncol Lett 2014;8:1087–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, Li J, Yu Y, et al. Shikonin controls the differentiation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by inhibiting AKT/mTOR pathway. Inflammation 2019;42:1215–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang FY, Hu Y, Que ZY, et al. Shikonin inhibits the migration and invasion of human glioblastoma cells by targeting phosphorylated β-catenin and phosphorylated PI3K/Akt: a potential mechanism for the 8Anti-Glioma efficacy of a traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Int J Mol Sci 2015;16:23823–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Chen Y, Wang T, Du J, et al. The critical role of PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in shikonin-induced apoptosis and proliferation inhibition of chronic myeloid leukemia. Cell Physiol Biochem Int J Exp Cell Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 2018;47:981–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu M, Zhao G, Zhang D, et al. Active fraction of clove induces apoptosis via PI3K/Akt/mTOR-mediated autophagy in human colorectal cancer HCT-116 cells. Int J Oncol 2018;53:1363–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porta C, Paglino C, Mosca A.. Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in cancer. Front Oncol 2014;4:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xuan Y, Hu X.. Naturally-occurring shikonin analogues – a class of necroptotic inducers that circumvent cancer drug resistance. Cancer Lett 2009;274:233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhen R, Xin L, Wen Z, et al. Synthesis and antitumour activity of β-hydroxyisovalerylshikonin analogues. Eur J Med Chem 2011;46:3934–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong WY, Chen XF, Shi J, et al. Design and synthesis of fluoroacylshikonin as an anticancer agent. Chirality 2013;25:757–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin HY, Li ZK, Bai LF, et al. Synthesis of aryl dihydrothiazol acyl shikonin ester derivatives as anticancer agents through microtubule stabilization. Biochem Pharmacol 2015;96:93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim Y, You YJ, Ahn BZ.. Naphthazarin derivatives (VIII): synthesis, inhibitory effect on DNA topoisomerase-I, and antiproliferative activity of 6-(1-acyloxyalkyl)-5,8-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinones. Archiv Der Pharmazie 2001;334:318–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sankawa U, Otsuka H, Kataoka Y, et al. Antitumor activity of shikonin, alkannin and their derivatives. II. X-ray analysis of cyclo-alkannin leucoacetate, tautomerism of alkannin and cyclo-alkannin and antitumor activity of alkannin derivatives. Chem Pharm Bull 1981;29:116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang JQ, Wang X, Wang Y, et al. Novel curcumin analogue hybrids: synthesis and anticancer activity. Eur J Med Chem 2018;156:493–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng X, Shi JB, Liu H, et al. Discovery of (4-bromophenyl)(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)methanone through up-regulating hTERT induces cell apoptosis and ER stress. Cell Death Dis 2017;8:e3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ke Y, Liang JJ, Hou RJ, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel Jiyuan Oridonin A-1,2,3-triazole-azole derivatives as antiproliferative agents. Eur J Med Chem 2018;157:1249–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahdjour S, Guardia JJ, Rodríguez-Serrano F, et al. Synthesis and antiproliferative activity of podocarpane and totarane derivatives. Eur J Med Chem 2018;158:863–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shankar R, Chakravarti B, Singh US, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 3,4,6-triaryl-2-pyranones as a potential new class of anti-breast cancer agents. Bioorg Med Chem 2009;17:3847–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Senwar KR, Sharma P, Reddy TS, et al. Spirooxindole-derived morpholine-fused-1,2,3-triazoles: design, synthesis, cytotoxicity and apoptosis inducing studies. Eur J Med Chem 2015;102:413–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris MH, Thompson CB.. The role of the Bcl-2 family in the regulation of outer mitochondrial membrane permeability. Cell Death Differ 2000;7:1182–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gillies LA, Kuwana T.. Apoptosis regulation at the mitochondrial outer membrane. J Cell Biochem 2014;115:632–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim J, Kim YC, Fang C, et al. Differential regulation of distinct Vps34 complexes by AMPK in nutrient stress and autophagy. Cell 2013;152:290–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J 2000;19:5720–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mizushima N. Methods for monitoring autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2004;36:2491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Y, Azad MB, Gibson SB.. Methods for detecting autophagy and determining autophagy-induced cell death. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2010;88:285–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Q LW, Sheng L, Zou C, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel asperphenamate derivatives. Eur J Med Chem 2016;110:76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiao YN, Wu LN, Xue D, et al. Marsdenia tenacissima extract induces apoptosis and suppresses autophagy through ERK activation in lung cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int 2018;18:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao D, Zhou Y, Zhu L, et al. Design, synthesis and structure-activity relationship studies of a focused library of pyrimidine moiety with anti-proliferative and anti-metastasis activities in triple negative breast cancer. Eur J Med Chem 2017;140:155–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crighton D WS, Prey JO, Syed N, et al. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell 2006;126:121–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi YH, Ding ZB, Zhou J, et al. Targeting autophagy enhances sorafenib lethality for hepatocellular carcinoma via ER stress-related apoptosis. Autophagy 2011;7:1159–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shrivastava A, Kuzontkoski PM, Groopman JE, et al. Cannabidiol induces programmed cell death in breast cancer cells by coordinating the cross-talk between apoptosis and autophagy. Mol Cancer Ther 2011;10:1161–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang FY, Xiao-Ming T, Xia W, et al. Mitochondria-targeted platinum(II) complexes induce apoptosis-dependent autophagic cell death mediated by ER-stress in A549 cancer cells. Eur J Med Chem 2018;155:639–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Avan A, Hassanian SM, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, et al. Targeting the Akt/PI3K signaling pathway as a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Curr Med Chem 2017;24:1321–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar S GS, Pathania AS, Manda S, et al. Fascaplysin induces caspase mediated crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy through the inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade in human leukemia HL-60 cells. J Cell Biochem 2015;116:985–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roy B, Pattanaik AK, Das J, et al. Role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MEK/ERK pathway in Concanavalin A induced autophagy in HeLa cells. Chem Biol Interact 2014;210:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janku F, McConkey DJ, Hong DS, et al. Autophagy as a target for anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011;8:528–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu YT, Tan HL, Shui G, et al. Dual role of 3-methyladenine in modulation of autophagy via different temporal patterns of inhibition on class I and III phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem 2010;285:10850–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.