Abstract

The aim of the current research was to provide a new method for mapping the developmental sequences of serial killers’ life histories. The role of early childhood abuse, leading to types of serial murder and behaviours involved in the murders, was analysed using Behaviour Sequence Analysis. A large database (n = 233) of male serial killers with known childhood abuse (physical, sexual, or psychological) was analysed according to typologies and crime scene behaviours. Behaviour Sequence Analysis was used to show significant links between behaviours and events across their lifetime. Sexual, physical, and psychological abuse often led to distinct crime scene behaviours. The results provide individual accounts of abuse types and behaviours. The present research highlights the importance of childhood abuse as a risk factor for serial killers’ behaviours, and provides a novel and important advance in profiling serial killers and understanding the sequential progression of their life histories.

Key words: behaviour sequence analysis, crime, homicide, profiling, serial killer

Homicide is legally defined as the killing of another person. Homicide is an all-inclusive term, and there are different subcategories of homicide, such as murder, multicide, and manslaughter. Serial homicide, as defined by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, is “the unlawful killing of two or more victims in separate events.” Serial homicide is an intentional, premeditated act, not a crime carried out on impulse or in response to a perceived provocation or threat (Reid, 2016). Athrough it is form of multicide, serial homicide is not to be confused with mass murder, which is defined as four or more murders that occur in one event, with no distinctive time lapse between them, or spree-killing, which is any murder that occurs at two or more locations with no emotional cooling-off period between (Douglas et al., 1992).

Advances in computational intelligence and the establishment of large datasets have meant that researchers in serial homicide are moving towards predictive models and understanding. In particular, researchers are now beginning to develop models to help to predict who is likely to commit serial homicide, and how to interpret offending patterns as a way to predict later offending behaviour (Hewitt, Beauregard, & Martineau, 2016; Ioana, 2013; Miller, 2014). Regardless of the type of prediction, to develop any such model, it is important that researchers understand the chain of events that preceded the homicides. One way in which researchers do this is by grouping related behaviours together, using a “thematic” or offending style typology approach (Grubin et al. 1997).

Typologies

Since the 1970s, investigative profilers at the FBI’s Behavioural Science Unit (BSU) have been analysing crime scenes in the attempt to generate ‘profiles’ of violent offenders. Profiles consist of aggregated data collected from several sources, which combine to indicate specific characteristics relevant to the offender (Douglas, Ressler, Burgess, & Hartman, 1986). These profiles, in turn, are meant to aid law enforcement officers in the detection and apprehension of violent offenders, including serial killers. Originally, the analysis of crime scenes revealed a dichotomized classification of a crime that was considered to be either organized or disorganized (Hazelwood & Douglas, 1980), the organized typology being a form of murder carried out by an individual who appeared to plan the crime, target the victims specifically, and displayed control (Douglas et al., 1986). Disorganized scenes, in contrast, exhibited a form of murder carried out by an offender who was less apt to plan the offence, who obtained victims by chance, and who behaved haphazardly during the crime (Douglas et al., 1986).

This original typology, that of the organized or the disorganized offender, was deemed overly simplistic and has since broadly expanded (Canter, 1994; Holmes & Rossmo, 1996; Turco, 1990). Recently, researchers have developed more sophisticated typologies including (1) visionary, mission-oriented, hedonistic, and power-control oriented killers (Holmes, De Burger, & Holmes, 1988); (2) thrill-motivated killers, murders for profit, and family slayings (Levin & Fox, 1985); and (4) travelling serial killers, local serial killers, and place-specific serial killers. Despite the development of refined typologies, research has found that there is no such thing as a prototypical serial killer, consequently limiting the usefulness of the typologies developed so far (Walters, Drislane, Patrick, & Hickey, 2015).

Profiles are created retrospectively – that is, after a crime had been committed. They are developed viay a thorough observation of the crime scene, interviews with surviving victims, and even wiretappings of taunts made by the subject to the victims’ families (Douglas et al., 1986). However, one limitation to this is that the profiles generated rely, to a large extent, on the use of educated guesses developed on the basis of data that may be unreliable. While profiles are undoubtedly a useful investigative tool that should not be overlooked, the accuracy of profiling could still be developed.

Studies have suggested that it is important to include personal histories and personality factors when proposing an ‘offender profile’ (Hazelwood & Warren, 2000). The FBI’s BSU also noted the value of this when they conducted a series of extensive interviews with several violent sexual offenders, including 25 serial killers, in the 1980s (Ressler, Burgess, & Douglas, 1988). The results from those interviews have helped to inform the development of criminal profiles today. The present study uses a broader categorization, such as those designed by Holmes and Holmes (1998). The present study includes influencing factors before the kill, such as personal histories and serial killers’ experiences of abuse.

Abuse

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines child abuse as “all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child” (World Health Organization, 1999, p. 80). Although this definition covers a spectrum of abuse, the three main types defined in the present study are physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. Physical child abuse relates to acts that cause actual physical harm or have the potential for harm. Sexual abuse is defined as those acts in which a child is used for sexual gratification. Psychological abuse includes the lack of an appropriate and supportive environment or acts that have an adverse effect on the emotional health and development of a child.

Research has suggested that the ‘profile’ of a serial murderer typically includes abuse during childhood (Ressler, Burgess, Douglas, & Depue, 1985). It is possible that this is due to habituation and tolerance of pain, depending on the extent to which the abuse had been experienced as violent or painful (Joiner, 2007). Childhood abuse has also been associated with later cognitive processing problems, which may lead to an aggressive thought pattern – for example, encoding errors, hostile attributional biases, accessing of aggressive responses, and positive evaluations of aggression (Dodge, Pettit, Bates, & Valente, 1995).

Furthermore, research has shown that there is a very strong link between early childhood abuse and individuals who kill for sexual gratification (Lust/rape typology), as previous research has found that all types of abuse, excluding neglect, were significantly higher in the lust typology serial killer population than in a controlled sample (Mitchell & Aamodt, 2005). On average, 50% of serial killers suggest that they have experienced psychological abuse, 36% have experienced physical abuse, and 26% have experienced sexual abuse (Mitchell & Aamodt, 2005). Therefore, abuse in childhood is linked to serial killers’ later behaviours; however, what is not known is the sequential pathway between childhood abuse and different types of serial killer. A method is needed that can systematically link and sequence childhood abuse with typology of the criminal and crime scene behaviours. The present study provides this novel methodological approach to understanding the link between childhood abuse and later serial killer behaviour.

Behaviour Sequence Analysis (BSA)

A useful method for understanding the dynamic relationship between progressions of behaviours and social interactions occurring over time is Behaviour Sequence Analysis (BSA; Beune, Giebels, & Taylor, 2010; Marono, Clarke, Navarro, & Keatley, 2018; Taylor, Keatley, & Clarke, 2017; Keatley, Barsky, & Clarke, 2016; Keatley, 2018). BSA, also referred to as lag sequence analysis, is a method for investigating how chains of behaviours and events are linked over time.

Behaviour Sequence Analysis involves the study of transitions between behaviour pairs (Marono et al., 2017). Sequences can be on large (lifetime, e.g., Keatley, Golightly, Shephard, Yaksic, & Reid, 2018) or small (millisecond, e.g., Marono et al., 2017) scales. In lag-one BSA, which the present study uses, the antecedent behaviour (e.g., type of abuse) is the first event in a pairing, and the sequitur (e.g., first murder behaviour) is the second behaviour in the pair. Obviously, there are intervening behaviours and events through the lifetime; however, the purpose of the present study is to highlight BSA as a method for understanding homicide and connecting established risk factors and behaviours. This provides a simplified model of types of abuse linked to type of murders. Put simply, a BSA will determine how likely it is, compared to chance, that a sequitur occurs following an antecedent. The analysis indicates which pairings of behaviours occur above the expected level of chance – for instance, if an individual suffers ‘abuse type A’, how likely is ‘Behaviour B’ or ‘Behaviour C’ to follow. Sequence Analysis is not limited to only two behaviours; it is possible to analyse the pattern between potentially unlimited numbers of behaviours (from the start to end of a sequence). This technique has been applied to a variety of behaviours and social interactions and is commonly applied to forensic contexts, such as rape cases (Ellis, Clarke, & Keatley, 2017; Fossi, Clarke, & Lawrence, 2005; Lawrence, Fossi, & Clarke, 2010), violent episodes between people (Beale, Cox, Clarke, Lawrence, & Leather, 1998; Taylor et al., 2017), and marital conflict (Gottman, 1979).

Present study

The present study uses a BSA approach to investigate the effects of different types of early childhood abuse (physical, psychological, and sexual abuse) on later serial killings. The pattern of actions explored begins with this early abuse, leading on to the typology of the serial killer. This is included in the analysis to indicate links between abuse and typology, rather than direct sequential effects.1 The effect of experiencing multiple types of abuse at the same time was also investigated. Typologies were classified into four groups, dependent on the serial killer’s motivation: lust, anger, power, and financial gain. The next behaviour explored was the crime scene behaviour – such as how the victim was killed and what was done with the body. Thus, the sequence from early childhood abuse, typology of the killer, and crime scene behaviours was analysed. While formal hypotheses are not made, owing to the novel nature of the research, several expected links can be outlined. First, it is likely that childhood sexual abuse will lead predominantly to sexual typologies, taking into account previous literature highlighting that violent upbringings influence later delinquency, adult criminality, and violence (Maxfield & Widom, 1996). It is also likely that individuals who have experienced early physical abuse will show a greater amount of violence – for example, signs of torture and overkill (infliction of excessive and unnecessary violence).

Methods

Sample

An all-male sample of 233 serial killers with a documented history of childhood abuse was collected. Numbers experiencing each type of abuse were as follows: psychological abuse (n = 35), physical abuse (n = 36), sexual abuse (n = 21), psychological and physical abuse (n = 88), physical and sexual abuse (n = 7), and physical, sexual, and psychological abuse (n = 46). The dates of first kill ranged from 1850 to 2014. The date of last kill ranged from 1893 to 2014. In calendar years of the sample at the time of their first kill ranged from 6 to 60 (M = 28, SD = 8.96), and their last kill ranged from 16 to 68 (M = 34, SD = 10), although the exact age in childhood when abuse occurred is unknown. The number of kills ranged from 3 to 138 within several countries: Brazil (n = 3), Canada (n = 6), Australia (n = 6), USA (n = 176), Argentina (n = 1), Columbia (n = 4), Ecuador (n = 1), England (n = 8), France (n = 4), Germany (n = 4), Italy (n = 1), Mexico (n = 2) Ireland (n = 1), Scotland (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 1), Russia (n = 5), South Africa (n = 7), and Spain (n = 2). As the sample had been obtained from secondary sources and so does not contain any studies with human participants, ethics approval was not needed.

Coding procedure

The sample was split according to the type of abuse experienced in childhood. The typology of the serial killer in each group was then coded (Lust/rape, power, financial gain, or anger) into the BSA. Lust/rape killers were those whose murders involved sexual elements, including rape, sexual assault without penetration, or symbolic sexual assault such as the insertion of a foreign object into body orifices (Douglas et al., 1992). Power killers were those who derived pleasure from having complete control over their victims. Financial gain killers were those who killed for motivations based on the accumulation of goods or finances. Anger killers were those who killed for motivations that stemmed from feelings of anger, frustration, or betrayal, whether real or imagined. The overall methods used across kills was also recorded for all killers.2 The final factor considered for each individual was what they had done with their victim’s body(s) after the murder (e.g., moved the body to a different location and buried it, hid the body at the crime scene, etc.). Percentages of participants for each individual were calculated at each stage.

A coding scheme was developed based on every recorded outcome/behaviour reported in the dataset. Given the straightforward nature of the task, there was no ambiguity over responses or coding. The typology of serial killers was assessed by forensic psychologists.

Statistical analysis

After data were coded into chains of discrete behaviours and categories, data were entered into the statistical software R (R Core Team, 2013) and analysed using a behaviour sequence analysis program developed by the researchers. The program calculated frequencies of individual behaviours, transitional frequencies, chi-square (χ2) statistics, and standardised residuals.

Results

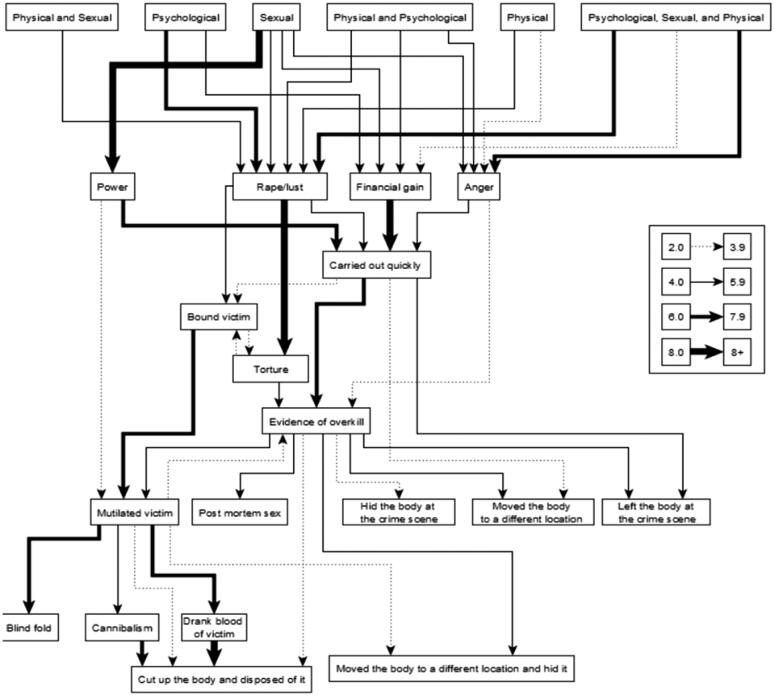

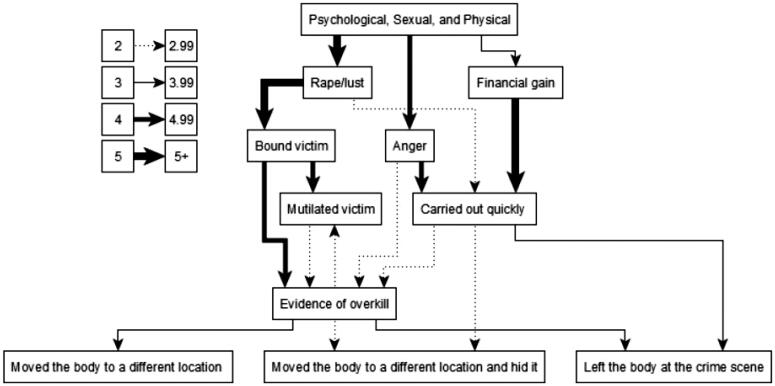

The main stage of BSA is to focus on the transitions between pairs of behaviours. Transition frequencies between antecedents and sequiturs are calculated, and chi-square analyses are indicated if these transitions occur above the level of chance. State transition diagrams can then be drawn, which indicate pairs of behaviours with high standardised residuals (SR). It is important to note that while pairs of behaviours can be connected to form longer chains, the analyses are only on pairs of behaviours. Longer chains, though intuitively appealing, are actually limited in terms of generalizability, owing to over-fitting of data. All of the transition lines in the diagram are significant (p < .05) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

State transition diagram for type of abuse experienced, typology, and crime scene behaviour. Standardised residuals indicated by line thickness (see key).

Importantly, Figure 1 shows that there is a clear distinction between type of abuse experienced and later typology of the serial killer. For example, experiences of sexual abuse most likely to lead to the power typology (n = 6, SR = 9.21), compared to other typologies. Rape/lust typology was the most common typology in the current dataset (n = 152). However, it had followed more frequently from psychological abuse (n = 10, SR = 7.06) and a combination of all three types of abuse (n = 12; SR = 7.04). There did not seem to be a strong connection between financial gain and any type of abuse or combination of abuse, as it was infrequent in all cases, particularly the experience of all three combined. There was no strong pattern between any single type of abuse and anger typology, and only 23 subjects classified as this typology. There was a clear pattern between rape/lust typology and torture of the victim (n = 16, SR = 9.59). There was a clear pattern between financial gain and the murder being carried out quickly (n = 12, SR = 8.33). An additional benefit of the BSA approach is that particular cases can be highlighted and analysed individually. For instance, the following analyses focused on each type of abuse sequence by itself. This allows researchers and investigators to refine their search parameters and to begin narrowing in on particular sequences based on evidence or interests.

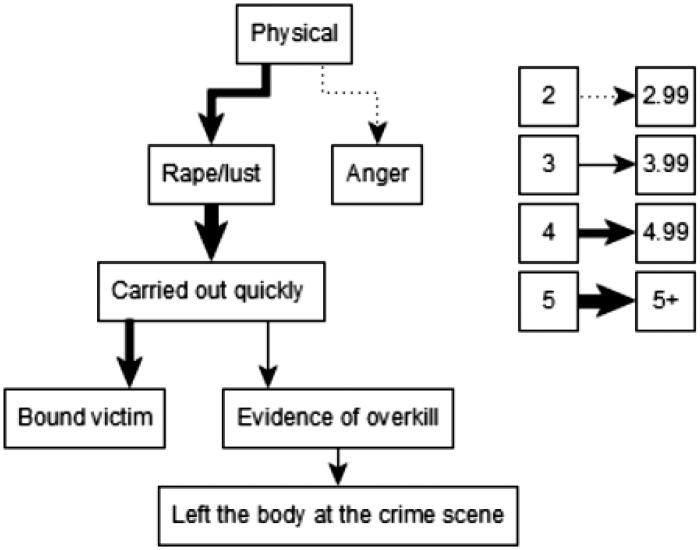

Physical abuse

For physical abuse (Figure 2), there was a distinct sequence between the experience of physical abuse and rape/lust typology (n = 6, SR = 4.80) and anger typology (n = 2, SR = 2.77). Those with rape/lust typologies were more likely to carry out the murder quickly (n = 5, SR = 5.75), and crime scenes exhibited signs of the victim having been bound (n = 3, SR = 4.64). There was also evidence of overkill, and in all cases where overkill occurred, the body had been left at the crime scene.

Figure 2.

State transition diagram for physical abuse, typology, and crime scene behaviour. Standardised residuals indicated by line thickness (see key).

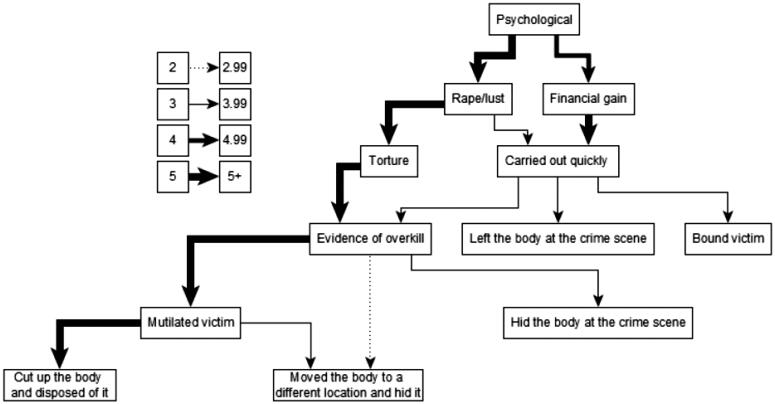

Psychological abuse

For psychological abuse (Figure 3), there was a distinct sequence between the experience of psychological abuse and rape/lust typology (n = 10, SR = 6.50) and financial gain (n = 5, SR = 4.60). Murders were carried out quickly in all cases where the motivation was financial gain; however, if the typology was rape/lust, then fewer were carried out quickly (n = 5, SR = 3.63). There was also a strong link between torture and evidence of overkill (n = 5, SR = 6.25), and evidence of overkill and mutilation of the body (n = 6, SR = 6.84).

Figure 3.

State transition diagram for psychological abuse, typology, and crime scene behaviour. Standardised residuals indicated by line thickness (see key).

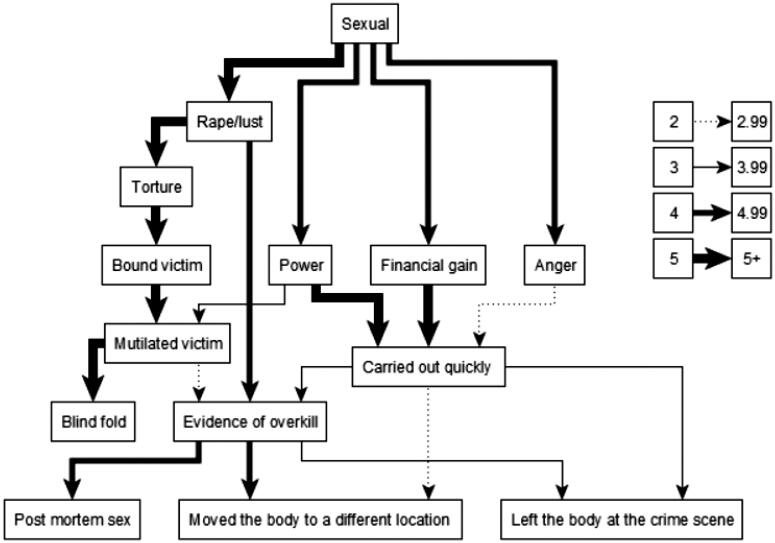

Sexualabuse

Unlike the other types of abuse, sexual abuse was linked to all four typologies (see Figure 4). The rape/lust typology was slightly more likely to the torture of victims (n = 4, SR = 5.92) compared to showing signs of overkill (n = 4, SR = 4.27). The power typology was more strongly related to carrying out the murder quickly (n = 4, SR = 5.23) than to mutilating the victim (n = 2, SR = 3.16). The anger typology showed a link to carrying out the murder quickly (n = 2, SR = 2.16), and financial gain was also linked to carrying out the murder quickly (n = 4, SR = 5.85). Finally, there were strong links between torturing and binding the victim (n = 4, SR = 9.39), and the victim being bound and mutilation (n = 4, SR = 8.63).

Figure 4.

State transition diagram for sexual abuse, typology, and crime scene behaviour. Standardised residuals indicated by line thickness (see key).

All types of abuse

When a combination of sexual, physical and psychological abuse was experienced (Figure 5), the rape/lust typology for killing was most likely to follow (n = 12, SR = 6.76). Rape/lust was more likely to lead to the victims being bound (n = 6, SR = 7.11) than to killers carrying out their murders quickly (n = 4, SR = 2.63). Subjects who killed for anger were more likely to carry out the murder quickly (n = 4, SR = 4.49) than show evidence of overkill (n = 2, SR = 1.61).Those who killed for financial gain carried out the murder quickly (n = 3, SR = 5.03).

Figure 5.

State transition diagram for typology and crime scene behaviour following experience of psychological, physical, and sexual abuse. Standardised residuals indicated by line thickness (see key).

Discussion

The main aim of the present study was to examine whether there were distinguishable sequences that occur after experiencing different types of abuse in childhood, leading to different typologies/motivations for killing victims, and how murders were carried out. The outcome is an insight into the sequential chains that different types of abuse result in for an individual. Within the current dataset, results indicate that different types of abuse affect later typologies and murder behaviours.

Previous literature suggests that early physical abuse leads to later aggression and violence (Widom, 1989). Current results partially supported this. Although those who were physically abused were more likely to demonstrate ‘overkill’ of their victim, the most specifically violent methods of kill were practised by those who had been sexually or psychologically abused in early life. For example, mutilation, torture, and binding the victim were more typical of serial killers who had experienced sexual abuse. Furthermore, those who had been sexually abused rarely showed evidence of overkill, and the murders tended to be carried out quickly. This was not the case for both physical and psychological abuse, as both showed evidence of overkill. The exact reason for this cannot be clarified from this sequence chain, although based on previous research (Briere & Elliott, 1994; Wyatt & Newcomb, 1990), it may be that these patterns emerge because those who have experienced sexual abuse suffer from deep-seated anger and self-blame, leading them to lash out and kill their victims quickly, and they are more likely to feel guilt or remorse afterwards and thus are unlikely to show evidence of overkill.

Furthermore, all recorded murders were carried out quickly by those who were classified as motivated by power. There was also no evidence of any torture, mutilation, or overkill. Although again, the sequence chain cannot direct determine the reason as to why this is, based on previous research (Canter & Wentink, 2004; Holmes & Holmes, 1998), a reason could be that this stems from a need to control the victim and assert dominance. Therefore, killers see the act of killing as a necessity, rather than obtaining any enjoyment out of the kill, per se. In these killings, there is, therefore, no unnecessary means of killing, infliction of unnecessary pain, or evidence of enjoyment.

Those who were classified as exhibiting rape/lust typology commonly engaged in post-mortem sex, regardless of the type of abuse experienced as a child. There was also no evidence of overkill in any of the cases, although torture was commonly used. A possible explanation for this is the presence of abnormal paraphilias or sexual sadism, which supports Dietz, Hazelwood, and Warren’s (1990) argument that psychopathic sexual sadists kill for the sheer pleasure of torturing and murdering their victims in a sexual way. Importantly, the experience of sexual abuse, whether isolated or experienced alongside physical and/or psychological abuse, led to the mutilation or torture of the victim. Similarly, individuals who classified as lust/rape typology where more likely to torture or mutilate their victims. This suggests a correlation with sexual behaviour and a need to inflict pain.

Additionally, results are incongruent with previous literature on typologies, as there was no consistent pattern for method of killing and disposal of the body within each typology. This supports the suggestion by Canter and Wentink (2004) that features of power/control typologies were consistent for serial killers rather than forming a distinct type. Thus, the reliability of isolated typologies is less mutually exclusive than previously believed, and more attention should be paid to what factors influence specific methods of killing than to the motivations of individual offenders. Indeed, it may be that the cross-sectional approach to typology defining could be developed to include temporal dimensions. The current analytical method can be used to show linkages between behaviours and events, over time, which may provide investigators with a clearer understand and method for developing typologies.

A limitation of the current research is the potential influence of additional life events that may intervene in the current diagrams, as these were not available to be analysed. These other variables and events may have effects on later behaviours; however, the present research outlines a new approach to understanding serial killers’ life histories, rather than a complete timeline. Given the nature of the coding and behaviour sequence analysis, future research can be added directly to the current data to extend the sequence pattern, and other influential factors can be added. Indeed, this research marks the beginning of a new framework for understanding life histories and behaviours of serial killers, which can be developed and expanded. This research underlines the important impact of childhood abuse on serial killers’ motivations and behaviours. Future research should aim to fill in the gaps between childhood abuse and other life events leading up to the first murder, and then further murders.

Notes

It is possible that other, unmeasured variables play an important role in the sequence; however, the current research is presented as a framework foundation on which more complex sequences can be built in the future. The methods and statistics are open to additions being imputed into the sequences at later times, to develop more complex sequential chains.

Owing to limitations of the dataset, behaviours for each sequential murder are not known. Therefore, overall behaviours across murders are presented in the current dataset. While we acknowledge this is a limitation of the study, it still indicates typical crime scene behaviours for each individual killer.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Abbie Marono has declared no conflicts of interest. Sasha Reid has declared no conflicts of interest. Enzo Yaksic has declared no conflicts of interest. David Keatley has declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Beale, D., Cox, T., Clarke, D.D., Lawrence, C., & Leather, P. (1998). Temporal architecture of violent incidents. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3(1), 65–82. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beune, K., Giebels, E., & Taylor, P.J. (2010). Patterns of interaction in police interviews: The role of cultural dependency. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(8), 904–925. doi: 10.1177/0093854810369623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briere, J.N., & Elliott, D.M. (1994). Immediate and Long-Term impacts of child sexual abuse. The Future of Children, 4(2), 54. doi: 10.2307/1602523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canter, D. (1994). Criminal shadows: Inside the mind of the serial killer. New York, NY: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Canter, D.V., & Wentink, N. (2004). An empirical test of holmes and holmes’s serial murder typology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 31(4), 489–515. doi: 10.1177/0093854804265179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, P.E., Hazelwood, R.R., & Warren, J. (1990). The sexually sadistic criminal and his offenses. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 18(2), 163–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, K.A., Pettit, G.S., Bates, J.E., & Valente, E. (1995). Social information-processing patterns partially mediate the effect of early physical abuse on later conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(4), 632–643. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.104.4.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J.E., Burgess, A.W., Burgess, A.G., & Ressler, R.K. (1992). Crime Classification Manual: A standard system for investigating and classifying violent crime. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J.E., Ressler, R.K., Burgess, A.W., & Hartman, C.R. (1986). Criminal profiling from crime scene analysis. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 4(4), 401–421. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2370040405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, H.E., Clarke, D.D., & Keatley, D.A.. (2017). Perceptions of behaviours in stranger rape cases: A sequence analysis approach. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 23(3), 328–337. [Google Scholar]

- Fossi, J.J., Clarke, D.D., & Lawrence, C. (2005). Bedroom rape sequences of sexual behavior in stranger assaults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(11), 1444–1466. doi: 10.1177/0886260505278716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman, J.M. (1979). Marital interaction: Experimental investigations. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grubin, D., Kelly, P., & Ayis, S. (1997). Linking serious sexual assaults. Mahipalpur, India: Home Office, Police Policy Directorate, Police Research Group. [Google Scholar]

- Hazelwood, R.R., & Douglas, J.E. (1980). The lust murderer. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, 49, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Hazelwood, R.R., & Warren, J.I. (2000). The sexually violent offender. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5(3), 267–279. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(99)00002-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, A., Beauregard, E., & Martineau, M. (2016). Can body disposal pathways help the investigation of sexual homicide? In Beauregard E. & Martineau M., (Eds.), The sexual murderer: Offender behaviour and implications for practice. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, R.M., De Burger, J., & Holmes, S.T. (1988). Inside the mind of the serial murder. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 13(1), 1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02890847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, R.M., & Holmes, S.T. (Eds.). (1998). Selected problems in serial murder investigations. In Contemporary perspectives on serial murder, 227–234. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781452220642.n16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, R.M., & Rossmo, D.K. (1996). Geography, profiling, and predatory criminals. Profiling violent crimes. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ioana, I.M. (2013). No one is born a serial killer. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 81, 324–328. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner, T. (2007). Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keatley, D.A., Barsky, A.D., & Clarke, D.D. (2016). Driving under the influence of alcohol: a sequence analysis approach. Psychology, Crime and Law, 23(2), 135–146. doi: 10.1080/1068316X.2016.1228933 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keatley, D.A., Golightly, H., Shephard, R., Yaksic, E., & Reid, S. (2018). Using behavior sequence analysis to map serial killers’ life histories. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi: 10.1177/0886260518759655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keatley, D.A. (2018). Pathways in crime: An introduction to behaviour sequence analysis. London: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, C., Fossi, J., & Clarke, D. (2010). A sequential examination of offenders’ verbal strategies during stranger rapes: the influence of location. Psychology Crime and Law, 16(5), 381–400. doi: 10.1080/10683160902754964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, J., & Fox, J.A. (1985). Mass murder: America’s growing menace (pp. 3–7). New York, NY: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marono, A., Clarke, D., Navarro, J., & Keatley, D. (2018). A sequence analysis of nonverbal behavior and deception. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 33(2), 109–117. doi: 10.1007/s11896-017-9238-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marono, A., Clarke, D.D., Navarro, J., & Keatley, D.A. (2017). A behaviour sequence analysis of nonverbal communication and deceit in different personality clusters. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 25(5), 730–744. doi: 10.1080/13218719.2017.1308783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield, M.G., & Widom, C.S. (1996). The cycle of violence: Revisited 6 years later. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 150(4), 390–395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L. (2014). Serial Killers I: Subtypes, patterns, and motives. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(1), 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2013.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, H., & Aamodt, M.G. (2005). The incidence of child abuse in serial killers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 20(1), 40–47. doi: 10.1007/BF02806705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienne, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, ISBN 3-900051-07-0, Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Reid, S. (2016). Compulsive criminal homicide: A new nosology for serial murder. Aggression and Violent Behavior, doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2016.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler, R.K., Burgess, A.W., & Douglas, J.E. (1988). Sexual homicide: Patterns and motives. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Ressler, R.K., Burgess, A.W., Douglas, J.E., & Depue, R.L. (1985). Violent crime. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, 54(8), 2–31. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, O., Keatley, D.A., & Clarke, D.D. (2017). A behavior sequence analysis of perceptions of alcohol-related violence surrounding drinking establishments. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi: 10.1177/0886260517702490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turco, R.N. (1990). Psychological profiling. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 34(2), 147–154. doi: 10.1177/0306624X9003400207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walters, B., Drislane, L.E., Patrick, C.J., & Hickey, E.W. (2015). Serial murder: Facts and misconceptions. Chicago, IL: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Widom, C. (1989). The cycle of violence. Science, 244(4901), 160–166. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization , (1999). Report of the consultation on child abuse prevention, 29–31. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, (document WHO/HSC/PVI/99.1). [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, G.E., & Newcomb, M.D. (1990). Internal and external mediators of women’s sexual abuse in childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 58(6), 758. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]