ABSTRACT

Purpose: Histoplasmosis is a fungal infection acquired through inhalation of Histoplasma capsulatum microconidia, mostly present in the Americas. Both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients can present a wide spectrum of signs/symptoms, ranging from mild disease to a severe, disseminated infection. The aim of this observational study is to describe histoplasmosis cases diagnosed in travelers and their clinical/radiological and therapeutic pattern.

Methods: Retrospective study at the Department of Infectious – Tropical Diseases and Microbiology (DITM) of Negrar, Verona, Italy, between January 2005 and December 2015.

Results: Twenty-three cases of acute histoplasmosis were diagnosed, 17 of which belong to the same cluster. Seven of the 23 patients (30.4%) were admitted to hospital, four of whom underwent invasive diagnostic procedures. Thirteen patients (56.5%) received oral itraconazole. All patients recovered, although nine (39.1%) had radiological persisting lung nodules at 12 month follow up.

Conclusions: Clinical, laboratory and radiological features of histoplasmosis can mimic other conditions, resulting in unnecessary invasive diagnostic procedures. However, a history of travel to endemic areas and of exposure to risk factors (such as visits to caves and presence of bats) should trigger the clinical suspicion of histoplasmosis. Treatment may be indicated in severe or prolonged disease.

KEYWORDS: Histoplasmosis, returning traveler, South America, diagnosis

Background

Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum is a dimorphic fungus endemic in the American continent, in particular in Missouri, Mississippi and Ohio river valleys of the United States [1]. Further, occasional outbreaks have been reported throughout the North American continent [2–4], and autochthonous cases have been also sporadically described in Asia (mostly India and China [5–9]), Africa [10], and Europe [11–14]). Surveys conducted with histoplasmin skin test in patients with advanced HIV infection showed wide ranges of prevalence, from 5 to 50% in Central America [15–18], 2.6% to 93% in Brazil [19], and 22.4% to 53.6% in Argentina [20,21].

Histoplasmosis is acquired through the inhalation of microconidia. The disease is usually mild in immunocompetent people, who can be either asymptomatic or experience a self-limiting disease with aspecific symptoms that include fever, respiratory, gastrointestinal and rheumatologic symptoms, malaise and night sweats [22]. The disseminated disease is often fatal if not promptly recognized, particularly in patients with HIV infection (histoplamsosis is an AIDS-defining condition), stem cell or solid organ transplantation receivers [22,23]. Recently, histoplasmosis has raised increasing attention in immunocompetent travelers [24]. In fact, histoplasmosis is the most common endemic mycosis acquired by European travelers [12–14,25–29]. However, the index of suspicion is frequently low in non- endemic areas, hence misdiagnoses are possible [23]. The gold standard of histoplasmosis is culture from clinical specimens [30].

Alternative available diagnostic tools rely on serological evidence of the fungal infection since the isolation of the etiologic agents in culture is often hard and time-consuming [31]. However, even indirect tests, such as serological and antigen urine tests are not common practice in non-endemic countries. Thus, a mixed approach of detailed travel history to endemic areas, clinical and radiological findings is necessary to diagnose histoplasmosis [30,32]. In this report, we describe a case-series of histoplasmosis in travelers during a 11-year period in a reference center for travel and tropical medicine in the North of Italy.

Methods

We retrospectively collected data from the Hospital electronic medical record (laboratory, radiological and microbiological tests as well as physical examination and patients’ past medical history) on the cases of histoplasmosis diagnosed in travelers who attended the Department of Infectious – Tropical Diseases and Microbiology (DITM) of Negrar, Verona, Italy, in an 11-year period (January 2005 – December 2015). We reviewed the medical records of all patients (either at the outpatient service or admitted to the ward), and retrieved data about demographic, epidemiological, clinical characteristics, diagnostic work-up, and treatment administered.

When not reported in the medical records, data on follow-up were assessed via phone calls. All records were anonymized.

Diagnostic criteria and case definitions

Cases were classified as ‘suspected’, ‘probable’ or ‘proven’ histoplasmosis on the basis of the criteria for case definition outlined below. As a pre-requisite, all had to have a history of travel to an endemic area for Histoplasma capsulatum.

Proven histoplasmosis: compatible clinical and/or radiological findings and positive culture, or histopathological evidence of histoplasmosis.

Probable histoplasmosis: compatible clinical and/or radiological findings; no alternate diagnosis considered more likely than histoplasmosis; at least one of the following: positive histoplasmin test, serology or urine-serum Histoplasma antigen, or a travel partner with proven Histoplasma infection.

Suspected histoplasmosis: compatible clinical and/or radiological findings; no alternate diagnosis considered more likely than histoplasmosis, or a travel companion with proven Histoplasma infection; favorable radiological and/or clinical response to adequate itraconazole therapy (Table 1, modified from Wheat [23] and De Pauw [33]). Moreover, the criteria for a syndromic classification are shown in Table 2 (adapted from Wheat’s definitions [23]).

Table 1.

Acute histoplasmosis in travelers: case definition.

| Proven | Probable | Suspect δ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recent travel (<= 3 months) to | + | + | + |

| Compatible clinical and/or | + | + | + |

| Mycological evidenceƟ | (+/-) | + | - |

| Positive culture or histology* | + | - | - |

*Histopathologic or direct microscopic demonstration of yeast intracellular forms or yeasts in tissue macrophages.

Ɵ Mycological evidence: histoplasmin test positivity and/or positivity of serology and/or positivity of urine-serum histoplasma antigen.

ᵟ No mycological evidence nor serologic evidence but:

belonging to a histoplasmosis cluster and/or

Efficacy of oral itraconazole (200 mg tid x 3 days, then 200 mg bid x 6–12 weeks) determined by resolution of symptoms and normalization of radiological finding.

Table 2.

Acute histoplasmosis in travelers: syndromic classification.

| Asymptomatic | Acute pulmonary | Rheumathologic | Disseminated (DH) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | - | + | - | + |

| Respiratory symptoms | - | + | - | +/- |

| Mediastinal involvement | - | +/- | - | +/- |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | - | +/- | - | +/- |

| Rheumathologic symptoms | - | +/- | + | +/- |

| Cutaneous involvement | - | +/- | - | +/- |

| Bone marrow and/or disseminated monocytic/macrophagic involvement | - | - | - | + |

| Ɵ Bone marrow involvement: leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia. Disseminated monocytic- macrophagic involvement: hepatosplenomegaly AND/OR increased liver enzymes. |

The serological test used in the study was the detection of precipitins by immunodiffusion (ID) to the H and M antigen of Histoplasma capsulatum (ID Fungal Antibody system- IMMY Inc. Norman, OK USA) [31]. The definitive diagnosis was made by cultivation of the organism from respiratory samples for 4 weeks, Broncoalveolar Lavage (BAL) in Sabouraud dextrose agar at 24°C and brain heart infusion agar at 37°C to obtain the yeast phase. Isolation of the pathogen required 1–2 weeks and identification was done on the basis of evidence of specific warted macroconidia of Histoplasma capsulatum and conversion to the yeast phase.

The study protocol was submitted to the Ethics Committee (Comitato Etico per la sperimentazione clinica delle Province di Verona e Rovigo), and received a waiver of consent (protocol 20901 of 26 April 2017).

The reporting of this study conforms to the STROBE statement.

Results

We retrieved 23 cases of histoplasmosis, including a cluster of 17 members of a naturalistic expedition to Ecuador, and 6 single cases in travelers. Seven patients (including 3/17 individuals belonging to the Ecuadorian cluster and 4/6 of the following patients) were admitted to hospital, whilst the others were diagnosed and treated as outpatients. The mean incubation period was 18.3 days (ranging from 5 to 35 days; the information was not available for 4 patients). Symptoms, results of the diagnostic work-up and treatment are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographics and travel characteristics of histoplasmosis cases diagnosed at DITM.

| Ecuador cluster (%) |

Others (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| n = 17 | n = 6 | |

| Sex male (%) | 11/17 (64.7) | 6/6 (100) |

| Mean age (range) | 38.5 (23–57) | 46.7 (30–71) |

| Comorbidities* | 4/17 (23.5) | 3/6 (50) |

| Immunocompetent | 17/17 (100) | 4/6 (66.7) |

| Reason of travel | Scientific expedition | Work (1), speleologist (3), tourism |

| (2) | ||

| Country of travel | Ecuador | Panama, Bolivia, Mexico (2), Cuba, unspecified country of South |

| America | ||

| Risk factor | Bat excreta, inhalation of contaminated soil | Bat excreta, inhalation of contaminated soil, outdoor activitiesα. |

*No evidence of immunedepression

α Outdoor activities: forest excursions, trekking, camping.

Cluster case series

The index case came to our attention because of pneumonia with respiratory impairment that did not respond to antibiotic therapy. Bilateral lung nodules were observed at chest X-ray. QuantiFERON-TB Gold (Qiagen ®) and urinary antigens for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Legionella pneumophila were negative; sputum samples yielded no growth of bacterial and/or mycobacterial pathogens. Due to the epidemiological link (history of sleeping in an endemic area for Histoplasma capsulatum, near bats’ excreta), histoplasmosis was suspected and itraconazole was administered, with rapid clinical improvement. Serological test for Histoplasma capsulatum was not available at that time. Following the diagnosis in the index case, we tried to contact all the other members of the expedition. This was a scientific expedition (Biodiversity Preservation Mission) to Ecuador from 19 July to 11 August 2006.

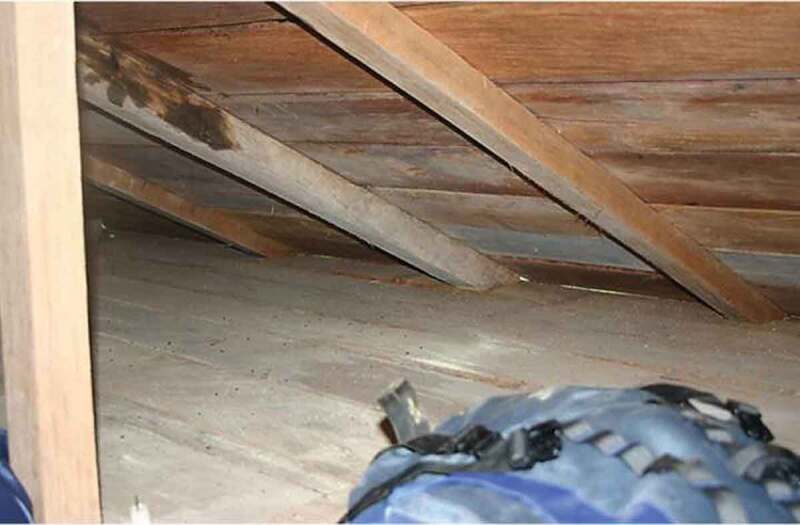

We were able to collect information about 23 more individuals (out of 27 members of the expedition), 16 of whom presented symptoms compatible with histoplasmosis. Two out of 16 (12.5%) patients who accepted to be tested had a positive serological test for Histoplasma capsulatum. All infected subjects had slept on the floor of the same lodge in the Otonga rainforest, where bat excreta were noticed (Figure 1). All subjects were immunocompetent, but one of them, with no apparent comorbidities, had a suspected, disseminated infection (respiratory and constitutional symptoms, increased liver enzymes and hepatosplenomegaly), with a negative Histoplasma capsulatum serology).

Figure 1.

The lodge in the Otonga rainforest where the subjects diagnosed with histoplasmosis (Ecuador cluster 2006) slept.

Immune-suppressed patients

Two patients affected by autoimmune conditions (Crohn’s disease and sarcoidosis), both taking low dose steroids, were diagnosed with proven histoplasmosis. One was traveling in Panama, and the other traveled through South America, without specifying the travel itinerary or giving information on risk factors. Both patients underwent BAL that resulted positive at culture for Histoplasma capsulatum. The patient with Crohn’s disease developed respiratory and systemic symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss) but no signs of monocytic-macrophagic system involvement. The patient received a long (12 month) course of oral itraconazole therapy, because of slow clinical and radiological improvement. Eventually, at the end of the therapy, the CT scan demonstrated resolution of the radiological findings. The patient with sarcoidosis had respiratory impairment and signs of disseminated disease (due to monocytic-macrophagic system and bone marrow involvement: leukopenia, anemia, increased ALT and LDH). He was diagnosed with proven histoplasmosis, on the basis of the histological examination of a mediastinal lymphonodal biopsy. Both patients had positive Histoplasma serology.

Immunocompetent patients

Four patients, with no known comorbidities, returning from Bolivia (1), Mexico (2), and Cuba (1), presented with symptoms and chest X ray abnormalities compatible with Histoplasma capsulatum infection; two had a positive serological test (see Table 4 for further details). Urinary antigens for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Legionella pneumophila were negative, QuantiFERON-TB Gold (Qiagen ®) were negative and sputum samples yielded no growth of bacterial and/or mycobacterial pathogens.

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics, diagnostic work up and treatment of histoplasmosis cases diagnosed at DITM.

| Ecuador cluster, n = 17 (%) | Others, n = 6 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| SYMPTOMS (%) | 17/17 (100) | 6/6 (100) |

| Fever | 8/17 (47) | 4/6 (67) |

| Respiratory | 9/17 (53) | 3/6 (50) |

| Gastrointestinal | 8/17 (47) | 1/6 (17) |

| Rheumathologic | 0/17 (0) | 2/6 (33) |

| Cutaneous/oral lesions | 4/17 (24) | 0/6 (0) |

| Constitutional | 4/17 (24) | 3/6 (50) |

| ABNORMAL LABORATORY EXAMS (%) | 11/17 (65) | 5/6 (83) |

| Inflammatory markersa | 6/11 (55) | 4/5 (80) |

| Blood cell count | 3/11 (27) | 1/5 (20) |

| LDH | 2/11 (18) | 4/5 (80) |

| Liver enzymes | 1/11 (9) | 1/5 (20) |

| POSITIVE HISTOPLASMA SEROLOGY (%) | 2/15 (13) | 2/6 (33) |

| ABNORMAL IMAGING (%) | 8/12 (67) | 6/6 (100) |

| Lung nodules | 4/8 (50) | 2/6 (33.3) |

| Consolidation | 4/8 (50) | 2/6 (33.3) |

| Mediastinal widening | 0/12 | 1/6 (16.6) |

| INVASIVE PROCEDURES (%) | 0/17 (0) | 4/6 (67) |

| TREATMENT (%) | 7/17 (41) | 6/6 (100) |

αinflammatory markers: C reactive protein (CRP), erythrosedimentation rate (ESR). LDH: lactate dehydrogenase.

Main results

The main demographic and travel-related characteristics of all patients are summarized in Table 3.

Overall, probable cases were two, both belonging to the Ecuador cluster, and proven cases among the patients diagnosed in the following years were also two. All other cases were classified as suspected.

Thirteen patients (7/17 belonging to the Ecuador cluster and all the other 6 single patients) received antifungal therapy with itraconazole 200 mg tid po x 3 days and then bid po for 6 to 12 months according to symptom duration, while the remaining 10 patients had only mild symptoms or a self-limiting disease and thus they were not treated. None of the patients belonging to the Ecuador cluster underwent any invasive diagnostic procedures, whereas 4 of the other group underwent bronchoscopy with BAL. All patients underwent a radiological follow up (chest CT scan every 6 months), up to 1 year after the resolution of symptoms. All patients, irrespective of whether they received antifungal treatment or not, recovered, although 9 presented persistence of the radiological findings. Serology was performed at the 12-month follow up for all patients, resulting negative for all.

Discussion

The diagnosis of histoplasmosis can be challenging outside endemic areas, as symptoms are not specific and the diagnosis is often presumptive. However, an accurate travel history is fundamental to consider histoplasmosis in the differential diagnosis: the epidemiological context (endemic country visited) and the type of travel (exposure to caves, bats, and activities involving manipulation/inhalation of soil/dust) can trigger clinical suspicion. In our case series, almost all patients had reported exposure to bat excreta in endemic areas.

When individuals participating in the same journey develop similar signs and symptoms, along with compatible radiologic findings, invasive procedures were not required. In fact, in the cluster cases, after ruling out other conditions with similar clinical and radiological presentation (such as pneumonia, tuberculosis and sarcoidosis), bronchoscopy with BAL was only performed in four out of 23 patients (17%). However, proven histoplasmosis was diagnosed in just two (8.5%) patients, both with autoimmune conditions (Crohn’s disease and sarcoidosis). On the other hand, the third patient affected by the disseminated form was an immunocompetent individual. Although more frequent in immunocompromised patients, severe histoplasmosis can also affect otherwise healthy subjects, and it is important to promptly make the diagnosis in order to avoid delays that could favor a progression of the disease [34,35]. Routine laboratory tests were usually normal or with nonspecific alterations, hence they did not represent a possible clue for diagnosis. Also, just 26.6% of cases were confirmed by serology (4 out of 15 individuals tested). This is presumably due to the short interval between the onset of symptoms and execution of the test that needs 4–8 weeks from acute infection to turn positive [22]. Indeed, the immunodiffusion serology test is slightly less sensitive than the complement fixation test and may have caused some false negative results. Urinary and serum antigen tests would be more useful for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in the acute phase [22,33], but they are not widely available in Europe. Moreover, 13/23 (56%) of our patients were treated with itraconazole. Although IDSA 2007 treatment guidelines suggests treating patients with persistent symptoms for more than 4 weeks, we anticipated the treatment in order to decrease symptom duration and favor the clinical resolution of the disease [36]. According to Stoffolani’s review of paper published up to the end of 2016, only 25% of immunocompetent travelers received an antifungal treatment, which is a much lower proportion than in our series [37]. However, if considering only clusters from Staffolani’s review, the proportion of treated individuals was much higher (45% in 45 clusters, ranging from 0% to 100%) [37]. These differences are due to variable virulence or infectious burden of the fungal strains, to different degrees of clinical severity, to the variability in clinicians’ adherence, to guidelines, and to the influence of belonging to a group with the same illness [37]. Nine (39%) of our patients had persistent radiological findings after the resolution of symptoms, thus highlighting the necessity of radiological follow-up after the treatment [36]. Considering the negative serology at 12-month follow up; antibodies might have cleared quickly after the resolution of the infection, as suggested by previous reports. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude that some suspected cases were erroneously classified as histoplasmosis [32,38].

Limitations of the study

The retrospective design might have limited the availability and quality of some information. Moreover, most of the cases did not have a proven diagnosis of histoplasmosis. A large proportion of our patients were part of a cluster, and this could have skewed the epidemiological/clinical features toward this rather homogeneous group. Moreover, according to literature, most cases of symptomatic or mild histoplasmosis resolve without treatment and it is hard to determine a causal relationship between itraconazole administration and resolution of symptoms. Finally, misclassification of some suspected cases is possible, though the travel history was highly suggestive.

Conclusion

Patients with respiratory symptoms and recent travel in endemic areas for histoplasmosis should be required to provide an accurate travel history in order to investigate a possible risk of inhalation of microconidia. When the index of suspicion raises (belonging to a cluster or because of specific at-risk activities), in cases of severe or persisting symptoms not responding to conventional antibiotic therapy and after exclusion of other possible etiologies, we suggest an empirical therapy with oral itraconazole and adequate follow-up. In our opinion, this approach might avoid hospital admission, invasive procedures, and treatment delay.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Edwards PQ, Klaer JH.. World wide distribution of histoplasmosis and histoplasmin sensitivity. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1956;5:235–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Histoplasmosis outbreak associated with the renovation of an old house- Quebec, Canada, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014. January;3:41–1044. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Public Health Agency of Canada . Locally acquired histoplasmosis cluster, Alberta, 2003. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2005. December 15;31(24):255–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Anderson H, Honish L, Taylor G, et al. Histoplasmosis cluster, golf course, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006. January;12(1):163–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pan B, Chen M, Pan W, et al. Histoplasmosis: a new endemic fungal infection in China? Review and analysis of cases. Mycoses. 2013;56:212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhao B, Xia X, Yin J, et al. Epidemiological investigation of histoplasma capsulatum infection in China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2001;114:743–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wen FQ, Sun YD, Watanabe K, et al. Prevalence of histoplasmin sensitivity in healthy adults and tuberculosis patients in Southwest China. J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34:171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Goswami RP, Pramanik N, Banerjee D, et al. Histoplasmosis in eastern India: the tip of the iceberg? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:540–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gopalakrishnan R, Nambi PS, Ramasubramanian V, et al. Histoplasmosis in India: truly uncommon or uncommonly recognized? J Assoc Physic India. 2012. October;60:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bahr NC, Sarosi GA, Meya DB, et al. Seroprevalence of histoplasmosis in Kampala, Uganda. Med Mycol. 2016. March;54(3):295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lo Cascio G, Ligozzi M, Maccacaro L, et al. Diagnostic aspects of cutaneous lesions due to histoplasma capsulatum in African AIDS patients in nonendemic areas. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003. October;22(10):637–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Farina C, Gnecchi F, Michetti G, et al. Imported and autochtonous histoplasmosis in Bergamo province, Northern Italy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ashbee HR, Evans EGV, Viviani MA, et al. Histoplasmosis in Europe: report on an epidemiological survey from the European confederation of medical mycology working group. Med Mycol. 2008;46:57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Farina C, Rizzi M, Ricci L, et al. Imported and autochtonous histoplasmosis in Italy: new cases and old problems. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2005;22:169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Laniado Laborin R. Coccidioidomycosis and other endemic mycoses in Mexico. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2007;24:249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gutierrez ME, Canton A, Sosa N, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS in Panama: a review of 104 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1199–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cermeno JR, Hernandez I, Cermeno JJ, et al. Epidemiological survey of histoplasmine and paracoccidioidine skin reactivity in an agricultural area in Bolivar state, Venezuela. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cermeno JR, Cermeño JJ, Hernández I, et al. Histoplasmine and paracoccidioidine epidemiological study in Upata, Bolivar State, Venezuela. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10(3):216–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fava SC, Fava Netto C. Epidemiologic surveys of histoplasmin and paracoccidioidin sensitivity in Brasil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1998;40:155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].de Komaid AVG, Duran AE, Histoplasmosis in talianern argentina . II: prevalence of histoplasmosis taliane and paracoccidioidomycosis in the population of Chuscha, Gonzalo and Potrero in the province of Tucuman. Mycopathologia. 1995;129:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].de Komaid AVG, Duran AE, de Kestelman IB. Histoplasmosis and paracoccidioidomycosis in northwestern Argentina. III: epidemiological survey in Vipos, La Toma, and Choromoro Trancas, Tucuman, Argentina. Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15:383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wheat LJ, Azar MM, Bahr NC, et al. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:207–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wheat LJ. Histoplasmosis: a review for clinicians from non endemic areas. Mycoses. 2006;49:274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Norman FF, Martín‐Dávila P, Fortún J, et al. Imported histoplasmosis: two distinct profiles in travelers and immigrants. J Travel Med. 2007;24(4):258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gascón J, Torres JM, Jiménez M, et al. Histoplasmosis infection in Spanish travelers to Latin America. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:839–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ansart S, Pajot O, Grivois JP, et al. Pneumonia among travelers returning from abroad. J Travel Med. 2004;11(2):87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ardizzoni A, Baschieri MC, Manca L, et al. The mycoarray as an aid for the diagnosis of an imported case of histoplasmosis in an Italian traveler returning from Brazil. J Travel Med. 2013;20(5):336–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gascón J, Torres JM, Luburich P, et al. Imported histoplasmosis in Spain. J Travel Med. 2000;7(2):89–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sotgiu G, Mantovani A, Mazzoni A. Histoplasmosis in Europe. Mycopathol Mycol Appl. 1970;41:53–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Azar MM, Hage CA. Laboratory diagnostics for histoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(6):1612–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Guimarães AJ, Nosanchuk JD, Zancopé-Oliveira RM. Diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Braz J Microbiol. 2006;37(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Segel MJ, Rozenman J, Lindsley MD, et al. Histoplasmosis in Israeli travelers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015. June;92(6):1168–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections. Coop Group and National Institute of Allergy and Infect Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) consensus group. Clin Inf Dis. 2006. June 15;46:1813–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Niknam N, Malhotra P, Kim A, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis presenting as diabetic keto acidosis in an immunocompetent patient. Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2016217915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bonsignore A, Orcioni GF, Barranco R, et al. Fataldisseminated histoplasmosis presenting as FUO in an immunocompetent Italian host. Leg Med(Tokyo). 2017. March;25:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, Infectious Diseases Society of America . et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007. October 1;45(7):807–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Staffolani S, Buonfrate D, Angheben A, et al. Acute histoplasmosis in immunocompetent travelers: a systematic review of literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2018. December 18;18(1):673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Joseph Wheat L. Current diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Trends Microbiol. 2003. October;11(10):488–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]