Abstract

Objectives. To determine the effect of new therapies and trends toward reduced mortality rates of melanoma.

Methods. We reviewed melanoma incidence and mortality among Whites (the group most affected by melanoma) in 9 US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry areas that recorded data between 1986 and 2016.

Results. From 1986 to 2013, overall mortality rates increased by 7.5%. Beginning in 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration approved 10 new treatments for metastatic melanoma. From 2013 to 2016, overall mortality decreased by 17.9% (annual percent change [APC] = −6.2%; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −8.7%, −3.7%) with sharp declines among men aged 50 years or older (APC = −8.3%; 95% CI = −12.2%, −4.1%) starting in 2014. This recent, multiyear decline is the largest and most sustained improvement in melanoma mortality ever observed and is unprecedented in cancer medicine.

Conclusions. The introduction of new therapies for metastatic melanoma was associated with a significant reduction in population-level mortality. Future research should focus on developing even more effective treatments, identifying biomarkers to select patients most likely to benefit, and renewing emphasis on public health approaches to reduce the number of patients with advanced disease.

Mortality rates for many cancers have declined gradually since the early 1990s, but the overall melanoma mortality rate had been rising. Increases in melanoma mortality were highest among older individuals, particularly men.1 Since 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 10 new therapies for the treatment of metastatic melanoma, including first- and second-generation immune checkpoint blocking antibodies (anti-CTLA-4 [T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4] and anti-PD-1 [programmed death protein 1], respectively) and B-RAF proto-oncogene (BRAF) and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitors, as well as talimogene laherparepvec.2 We investigated whether these drugs may have had an effect on population-level mortality data because 6 of these 10 agents were approved between 2011 and 2014.

METHODS

We examined the most recent melanoma incidence and mortality data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. We used SEER∗Stat Version 3.8.53 to collect incidence data from the 9 US SEER registry areas (Atlanta, GA; Connecticut; Detroit, MI; Hawaii; Iowa; New Mexico; San Francisco–Oakland, CA; Seattle–Puget Sound, WA; and Utah) that recorded data between 1986 and 2016, the most recent year available, covering approximately 9.4% of the US population. We limited our analysis of incidence data to White individuals, because more than 90% of melanoma in the United States occurs among this population.1

We coded incident melanomas of the skin according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3; Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000), histological tumor classification. We obtained overall age-adjusted incidence rates for men and women aged 20 years or older stratified into 10-year increments (melanoma is rare among individuals younger than 20 years). We used SEER∗Stat to collect mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics national database of death certificates.4 We selected melanoma of the skin as cause of death, which was determined by the ICD codes and rules in use at the time of death.5 The mortality analysis was limited to White persons, stratified by age and sex, from 1986 to 2016, the most recent year available. We also used SEER’s Incidence-Based Mortality database to examine stage at diagnosis of fatal melanomas in those aged 20 years or older. Stage at diagnosis was stratified by localized, regional, and distant disease via the SEER historic stage A recode. Cases were selected by the melanoma of the skin ICD-O-3 site recode and cause of death.

We used the Joinpoint Regression Program 4.5.01 to analyze incidence and mortality trends. The software generated joined linear segments on a log scale. We set the maximum number of possible joinpoints to 5, based on the number of data points in the series.6 A permutation test was used to determine the location of the joinpoints, when the change in trend was statistically significant.7 The slope of each line was recorded as the annual percent change (APC) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). APCs were considered statistically significantly different from zero when P values were less than .05.

RESULTS

Between 1986 and 2016, incidence rates of melanoma for the White population aged 20 years or older increased by 108.0% with an APC of 2.7% (95% CI = 2.5%, 2.9%). Incidence rates increased in men aged 50 years or older by 178.4% with an APC of 3.4% (95% CI = 3.2%, 3.7%) and in women aged 50 years or older by 142.1% with an APC of 3.2% (95% CI = 3.0%, 3.5%). Since 2005, the overall age-adjusted APC declined slightly, from 3.2% to 1.7% (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

For cutaneous melanoma mortality, we found 2 distinct trends over the past 30 or more years. Between 1986 and 2013, overall mortality increased by 7.5% with an APC of 0.2% (95% CI = 0.1%, 0.3%). Between 1986 and 2014, mortality among men aged 50 years or older increased by 35.4% with 2 statistically significant APC increases of 1.9% (95% CI = 1.5%, 2.3%) and 1.7% (95% CI = 1.1%, 2.2%) over most of the period. Between 1986 and 2013, mortality among women aged 50 years or older increased by 4.2% with an APC of 0.2% (95% CI = 0.1%, 0.4%).

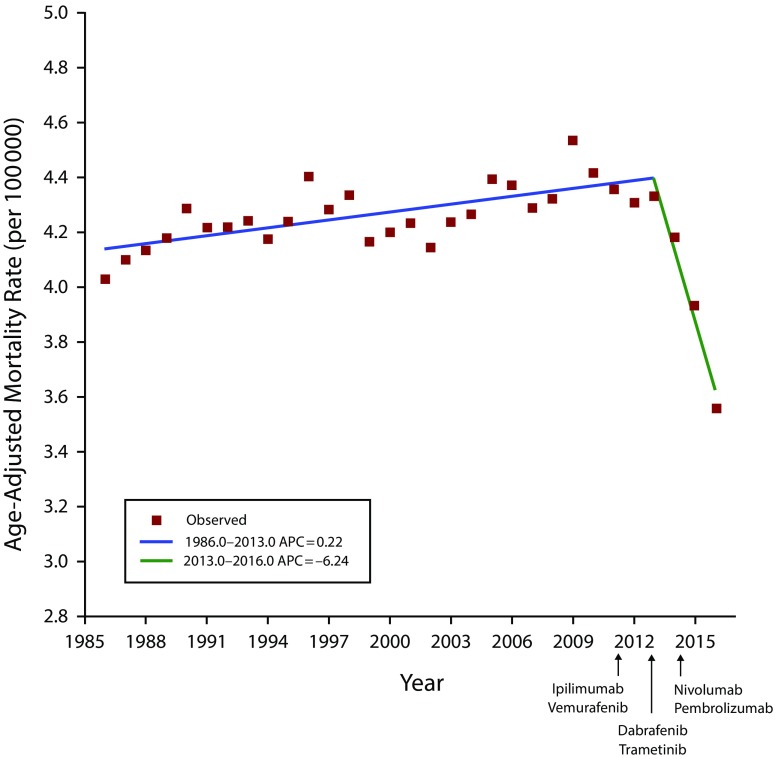

By contrast, between 2013 and 2016, overall mortality rates declined sharply by 17.9%. The APC decreased by 6.2% in the general population (95% CI = −8.7%, −3.7%; Figure 1), 8.3% among men aged 50 years or older (starting in 2014; 95% CI = −12.2%, −4.1%), and 5.8% among women aged 50 years or older (95% CI = −8.9%, −2.5%). The decrease between 2013 and 2016 was seen in nearly every 10-year age subset (Figure B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) despite an overall incidence rate that rose slightly and decreased for patients initially diagnosed with local, regional, or distant disease (Figure C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

Joinpoint Regression Analysis of Melanoma Mortality in Overall White Population Aged 20 Years or Older: US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results, 1986–2016

Note. APC = annual percent change. APCs were significantly different from zero at α = .05.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis of more than 30 years of US cancer data suggests that the long-term trend of increasing melanoma mortality has reversed. The decline was driven by substantial decreases in mortality among men aged 50 years or older beginning in 2014 and among women aged 50 years or older beginning in 2013. This 4-year decline in melanoma mortality of 17.9% surpasses the most pronounced 4-year declines for 4 other major cancers: prostate (14%), breast (8%), lung (8%), and colon cancer (5%).4

At least 2 possible reasons account for this decline: improved treatments for advanced disease and education and early detection resulting in migration toward earlier-stage melanomas with a greater chance of surgical cure. For the latter, SEER data indicated that the median tumor thickness decreased from 0.73 millimeters to 0.58 millimeters between 1989 and 2009, likely reflecting improved education and early detection by the public and professionals.8 This small decrease is not associated with changes in prognosis, so it is unlikely to be driving the mortality reduction.

The dramatic multiyear decline in mortality coincided with the introduction of multiple new and efficacious treatments for metastatic melanoma. Currently, 5-year survival ranges between 30% and 50% compared with historical estimates of less than 10%.9–11 Given the increased incidence of melanoma throughout this period (1986–2016) and the lack of stage migration, these data strongly suggest that the mortality decline was the result of the extended survival associated with these treatments. This conclusion was supported by Dobry et al.,12 who identified a 31% relative improvement in overall survival of 17 975 hospital-based metastatic melanoma patients who presented for treatment after the FDA’s initial approvals, compared with before 2011. However, during the last year those data were available (2015), only 37% of those stage IV patients received advanced therapies. Determining a true count of individuals who go untreated is vital to public health planning to ensure that access to new treatments is more widely available.

This analysis had limitations. Although mortality data were reported for all 50 states, only the original 9 SEER sites provided incidence data for the full 30 or more years. Use of population-based statistics does not provide patient-level treatment details, so the proportion of melanoma patients who actually received the new treatments is unknown. We also lacked tumor thickness data, which could have provided better information on recent trends in stage migration.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a statistically significant, multiyear reduction in the mortality rate of cutaneous melanoma across an entire nation. It shows progress in translating clinical trial survival data into improvements in population-level mortality. To accelerate these trends and improve overall patient outcomes, continued investment in medical and public health research should focus on (1) developing even more effective treatments; (2) identifying biomarkers to select patients most likely to benefit from particular therapies, while sparing others the risk of the potentially severe toxicities and high costs of treatment; and (3) renewing emphasis on public health approaches, such as raising public and professional awareness of melanoma and its early warning signs, especially in adults aged 50 years or older, to reduce the number of patients who require treatment of advanced disease.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

D. Polsky has the following potential conflicts of interest to disclose: in-kind laboratory services and support from Bio-Rad Laboratories and contract research with Novartis. J. Weber has the following potential conflicts of interest to disclose: consultant to Merck, GSK, Genentech, BMS, Astra Zeneca, Incyte, Celldex, CytoMx, Takeda, and Sellas; equity in Altor, CytoMx, Protean, and Biond; named on a PD1 patent by Biodesix; and named on a CTLA4 patent by Moffitt Cancer Center.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Because the study involved only cancer registry data, it did not require institutional review board approval.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geller AC, Miller DR, Annas GD, Demierre MF, Gilchrest BA, Koh HK. Melanoma incidence and mortality among US Whites, 1969-1999. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1719–1720. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute. Drugs approved for melanoma. June 2019. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/melanoma. Accessed November 18, 2019.

- 3.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Available at: http://www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed May 12, 2019. SEER∗Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 9 Regs Research Data, November 2018 Sub (1975-2016) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked to County Attributes - Total US, 1969-2017 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program. Released April 2019, based on the November 2018 submission.

- 4.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Available at: http://www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed May 12, 2019. SEER∗Stat Database: Mortality - All COD, Aggregated With State, Total US (1969-2016) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment>, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program. Released December 2018. Underlying mortality data provided by National Center for Health Statistics ( http://www.cdc.gov/nchs)

- 5.Jemal A, Ward EM, Johnson CJ et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2014, featuring survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(9) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance Research Program. Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) and Confidence Interval. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2017. Available at: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/help/joinpoint/setting-parameters/method-and-parameters-tab/number-of-joinpoints. Accessed June 5, 2019.

- 7.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaikh WR, Dusza SW, Weinstock MA, Oliveria SA, Geller AC, Halpern AC. Melanoma thickness and survival trends in the United States, 1989 to 2009. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108(1):pii: djv294. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robert C, Grob JJ, Stroyakovskiy D et al. Five-year outcomes with dabrafenib plus trametinib in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):626–636. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R et al. Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1535–1546. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6199–6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobry AS, Zogg CK, Hodi FS, Smith TR, Ott PA, Iorgulescu JB. Management of metastatic melanoma: improved survival in a national cohort following the approvals of checkpoint blockade immunotherapies and targeted therapies. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67(12):1833–1844. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2241-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]